-

apokrisis

7.8kAs I construct it, the mental and physical are two different perspectives on exactly the same stuff. — Pfhorrest

apokrisis

7.8kAs I construct it, the mental and physical are two different perspectives on exactly the same stuff. — Pfhorrest

I've heard every version of panpsychism. Different perspectives on the "same stuff" remains Cartesian unless you can truly dissociate your position from a substance ontology and shift to a process ontology.

In the one, stuff just exists. The goal of monism is achieved by granting that stuff some kind of fundamental duality (of properties, aspects, perspectives, whatever).

In the other, stuff is a condition with a developmental origin. The duality that concerns us is something that isn't fundamental but must eventually emerge. So the monism, the unity, has to come from triadic closure.

And that is what pansemiosis achieves as a model of reality.

The account doesn't assume its conclusions by just granting the duality as a fundamental ingredient of nature. Instead it is a based on a logic of development where a dualised state of affairs is what emerges due to a visible feedback relationship, an actual semiotic theory of how things are caused to be this way.

So do you have a formal theory of how fundamental stuff came to be dual-aspect in the way you require? How did this state of affairs come about exactly? -

creativesoul

12.2kAll things moral directly involve that which counts as acceptable/unacceptable thought, belief, and/or behaviour.

— creativesoul

I don’t disagree with that at all, I’m just not sure where you’re going with it in relation to the OP. — Pfhorrest

If you apply that to all the times that you've used the term "moral" some things will begin to stand out... You'll reach incoherence and/or self-contradiction, and be forced to rethink how to better say some of the things you've said when using the term. It also dispenses with historical moral discourse and the taxonomy used within. The distinction between prescriptive and descriptive dissolves. All sorts of things change in one's logical train of thought when and if they hold to that. "Is" and "ought" are both sometimes a part of moral claims. I've briefly laid out some of this earlier... that part went unattended. -

Isaac

10.3kthe point is not that we can expect everybody to agree with moral realism, the point is that it's not some completely out-there idea that everyone is going to balk at. — Pfhorrest

Isaac

10.3kthe point is not that we can expect everybody to agree with moral realism, the point is that it's not some completely out-there idea that everyone is going to balk at. — Pfhorrest

So. You said

The faults of the other views surveyed boil down to failing in some way or another these criteria:

-Holding moral statements to be capable of being true or false, in a way more than just someone agreeing with them, as people usually treat them

-Honoring the is-ought / fact-value divide.

-Independence of any controversial ontology (i.e. compatible with physicalism).

What you end up needing is some kind of non-descriptivist cognitivism.

I’m going to ignore Isaac’s constant harping on that first criterion above and just move on to actual philosophy of language stuff. — Pfhorrest

As far as I'm following the OP you've listed all the meta-ethical positions you've read about, claimed that something is wrong with each one and asked what other people to...

...discuss whether all of these conventional options are so far insufficient, and we're in need of something new and different — Pfhorrest

But less than a page in, you're going to ignore talk on the exact topic you specified (whether these theories are insufficient) on the grounds that at least a large minority of people already think they are. I'm confused as to what would be left to discuss.

You seem to have declared all previous meta-ethics inadequate on grounds which you refuse to discuss ("some people agree with me so there's no matter here to be argued"), then revealed incremental parts of your solution (the flaws in which you, again, refuse to discuss). As I said earlier, this is not an appropriate platform for proselytising. It's a discussion forum. If you want to present you ideas in a format which is less open to critique you might be better off with a blog or something. -

Pfhorrest

4.6kSo do you have a formal theory of how fundamental stuff came to be dual-aspect in the way you require? How did this state of affairs come about exactly? — apokrisis

Pfhorrest

4.6kSo do you have a formal theory of how fundamental stuff came to be dual-aspect in the way you require? How did this state of affairs come about exactly? — apokrisis

You seem to be reading way more into what I'm talking about than I am trying to say.

The fundamental elements of my ontology are interactions. For clarity, picture these as line segments, connecting two points. The interaction can be looked at from the perspective of either point: each point is, from its perspective, the subject of the interaction, and the other the object, but from the other's perspective it (the second) is the subject, and the other (the first) is the object. Neither of these is more or less right than the other, they're just different ways of looking at the same thing. "Mind" and "matter" in the floofy metaphysical senses correspond to those subject and object perspectives. (More substantial, ordinary senses of those words don't). There's no two kinds of stuff, just events that can be interpreted two ways, both objects (matter) and subjects (mind) emerging from bundles of those interaction events (which are respectively equivalent to properties of objects or experiences of subjects, depending on which perspective you take).

But this is getting way off topic. This thread is about moral semantics, not ontology, and I do plan another thread on this kind of ontological topic later. The only reason I've brought up ontology here is as a criterion for a workable meta-ethics, which shouldn't depend on any controversial ontological assumptions. By "compatible with physicalism" here I just mean doesn't require ontological commitments beyond the ordinary stuff virtually nobody disagrees with, rocks and trees and the like.

You seem to be making this very personal (as in about me) and being very uncharitable to my motives.

But less than a page in, you're going to ignore talk on the exact topic you specified (whether these theories are insufficient) on the grounds that at least a large minority of people already think they are. I'm confused as to what would be left to discuss. — Isaac

Maybe "whether" was a weasely way to say it. I was trying to be welcoming in my phrasing, "hey guys lets's talk about this topic". Here's a more blunt phrasing: There are substantial chunks of people who find each of the listed positions insufficient, for reasons I've listed. I agree with all of their reasons -- even though they mostly disagree with each other. I want to discuss ideas with other people about what possibilities remain when all those reasons are accounted for. It looks to me like the three big reasons common to most of those objections are, as I said, that a position is not compatible with ontological naturalism or physicalism (divine command theory, non-naturalism), that it doesn't honor the is-ought divide (naturalism, descriptivism generally), or it doesn't allows for moral claims to be genuinely truth-apt and not mere subjective opinions (subjectivisms, error theory, and non-cognitivisms). I have some ideas for something that I think wouldn't run into any of those objections, I'd like to discuss them, and I welcome any other ideas toward that same goal.

That you think one of those objections isn't a very good objection is really missing the point, and dragging the conversation into a repeat of the same damn conversation that you keep bringing into every damn thread I make. It's almost like you're on a witch hunt for any philosophical claim that could allow for the possibility of moral statements being objectively right or wrong. The thread about architectonics wasn't even supposed to be about my principles of commensurablism, but you derailed that entire thread into harping on one half of one of the four of them: the half of one that allows for moral objectivity. So I made a separate thread to be specifically about those principles altogether, and... you still made the entire thing into harping on that same half of one. I skipped a whole bunch of other thread ideas I had because I expected you would just do the same to them (and that other old, tired arguments would come up and derail them, so it's not entirely you), and instead I made this thread to discuss the language even used to talk about morality and how it related to other non-moral language... and you've still made the entire thing into the same damn debate about moral objectivism. I want to talk about other things besides that, things that tangentially relate to that but aren't all entirely about whether moral objectivism is possible or not, and I don't want every attempt to talk about anything that comes anywhere close to acknowledging moral objectivism to get sucked into the black hole of debating with you whether that's even possible.

revealed incremental parts of your solution (the flaws in which you, again, refuse to discuss) — Isaac

Where have I refused to discuss flaws in the parts of my solution? Nobody besides @Tarrasque has even acknowledged those parts of the thread, and I'm responding to their criticism, not ignoring it. -

Isaac

10.3kthere is virtually zero moral literature that takes the perspective of a "systems physicalism". — apokrisis

Isaac

10.3kthere is virtually zero moral literature that takes the perspective of a "systems physicalism". — apokrisis

Have you tried “The role of interoceptive inference in theory of mind,” by

Sasha Ondobaka, James Kilner, and Karl Friston, Brain Cognition, 2017 Mar; 112: 64–68. It doesn't cover all of what we might call morality, but it does tie Theory of Mind, empathetic responses, in nicely with Active Inference. I don't have a link, I'm afraid, but you might be able to track it down. -

Isaac

10.3kYou seem to be making this very personal (as in about me) and being very uncharitable to my motives. — Pfhorrest

Isaac

10.3kYou seem to be making this very personal (as in about me) and being very uncharitable to my motives. — Pfhorrest

You shut down conversation about the actual issue. I'm interested in how people think (that's why I'm here). Your ideas about morality were put off limits, so I thought I'd explore your ideas about discussion. You can put those off limits too if you want, there's plenty of other people to talk to. You are free to completely ignore me if you don't like the way I discuss things, I routinely ignore some people here for exactly that reason, we're not here out of duty, it's supposed to be interesting, not drudgery.

There are substantial chunks of people who find each of the listed positions insufficient, for reasons I've listed. I agree with all of their reasons -- even though they mostly disagree with each other. I want to discuss ideas with other people about what possibilities remain when all those reasons are accounted for. — Pfhorrest

You realise that's not just a 'more blunt' version, that;'s a completely different proposition. In the one you invite discussion about whether people find these reasons plausible, in the second you say you only want to discuss solutions to them with people who already agree that they are.

It's almost like you're on a witch hunt for any philosophical claim that could allow for the possibility of moral statements being objectively right or wrong. — Pfhorrest

Ha! That's really funny that you should put it that way, it gives an interesting insight into the other side of the coin, you think I'm on a witch hunt to destroy any philosophical claim of moral objectivity, it puts me as the active player (destroying the claims) and the people actually making the claims as merely passive. For me, of course, if you didn't keep setting up new threads to make the same claim I wouldn't have six different places in which to dispute it. To me it feels like you just really really want this system of yours to be accepted and everywhere some part of it isn't you say "I don't want to discuss that bit" and make a new thread about some other aspect of it. But each new thread you can't resist mentioning the parts you claim not to be discussing in the hope that they'll be thereby tacitly accepted.

I don't know you so I'm not making any claims to your personal situation, but as a psychological phenomena, it's very common in those who've turned away from religion in adolescence or later. Neural pruning early in childhood, I think, makes it difficult for those who've been raised with the idea of 'religious absolute truth' to deal with a world in which there's no such thing. They construct elaborate (usually pseudo-scientific) models to derive their replacement 'absolute truth' because they've simply no mechanisms to manage the uncertainty.

This may or may not be the case for you, I couldn't possibly know, but the thought processes which accompany these super-constructions, fascinates me. That's the reason why I engage with them whenever I find them. If that's a 'witch hunt' then so be it. -

Pfhorrest

4.6kYou shut down conversation about the actual issue — Isaac

Pfhorrest

4.6kYou shut down conversation about the actual issue — Isaac

I shut down an attention-sucking tangent. Now this is becoming another and I would like to shut it down so that more productive conversation can take place instead.

You are free to completely ignore me if you don't like the way I discuss things, I routinely ignore some people here for exactly that reason, we're not here out of duty, it's supposed to be interesting, not drudgery. — Isaac

I would like to do that. Replying to you is drudgery and the apparent difference in our time zones means I only see your posts as I’m about to go to bed or first thing in the morning, making what I mean to be a pleasurable pastime something that feels like a chore instead.

You like looking into how other people think, maybe start a thread about why people like me feel obligated to try to give a polite and thoughtful response to everyone, and have such difficulty even politely steering a conversation without it exploding into bullshit like this.

It would be helpful to me if you would just not respond to me anymore, but if you have the same difficulty I do resisting the impulse to do so I guess I can’t complain.

it puts me as the active player (destroying the claims) and the people actually making the claims as merely passive — Isaac

In only one of those threads was I actually making the claim that objective morality is possible, and even then that was just an implication of but one of four related claims the thread as a whole was supposed to be about. In the thread before that I mentioned those four an an example of the more generally kind of systemic philosophy I wanted to discuss, and didn’t want to debate those particular principles there yet. In this thread, I’m didn’t set out to argue that there are objective morals, just to explore a moral semantics that (among other things) doesn’t rule them out, as that is a common objection to many theories of moral semantics.

In the architectonics thread you made the conversation about the principles I meant only to be an example. In the spin-off thread about those principles it was more on topic, but you still made it entirely about that one small aspect of a much broader topic, which drowned out any discussion there might have been about the rest. Here, you’re again making everything about whether or not there ARE objective morals, when the topic is what moral claims even mean, and “that would rule out any possibility of objective truth to moral claims” is just one of several common objections to many positions on that topic.

To me it feels like you just really really want this system of yours to be accepted and everywhere some part of it isn't you say "I don't want to discuss that bit" and make a new thread about some other aspect of it. But each new thread you can't resist mentioning the parts you claim not to be discussing in the hope that they'll be thereby tacitly accepted. — Isaac

Philosophy is full of a bunch of topics that interrelate to each other. Views on one topic have implications on views on another topic. But to keep conversations manageable, and on topic, we can’t always go following every tangent wherever it leads and plumb the depths of all if philosophy. If a view on one topic depends on a view on another topic, we need to be able to say “yes, it does, and that is my view on that topic” and then get back to the topic at hand instead of turning it into a debate about the that other topic.

I do think there are objective morals. All of my views on other topics are going to be consistent with that view. That doesn’t mean that every topic I talk about has to devolve into a debate about that one implication of the larger system that my views on that topic are a part of. -

Outlander

3.2kDang. This is a neat topic.

Outlander

3.2kDang. This is a neat topic.

Curious as to what both debaters think about the following statements.

As a child, pain is objectively bad. So is suffering, starvation, dehydration, neglect, abuse, etc. Any who disagree well I'm frankly curious. As I'm sure others would be. Basically why is what is bad for you, not bad for someone else? Because they're not you? Because they look different?

The needs of the many outweigh the needs of the few. Excluding the obvious question of 'why are they the few'. Is the idea without value? If a town of 10,000, with 9,000 infected with some sort of lethal contagion with no cure but who don't think they are, not worth erm.. neutralizing to save the 1,000 who would have perished otherwise?

Curious. Thanks. -

Isaac

10.3kAs a child, pain is objectively bad. So is suffering, starvation, dehydration, neglect, abuse, etc. Any who disagree well I'm frankly curious. — Outlander

Isaac

10.3kAs a child, pain is objectively bad. So is suffering, starvation, dehydration, neglect, abuse, etc. Any who disagree well I'm frankly curious. — Outlander

It depends what you mean by 'bad'. Pain, hunger and other physiological states are states whose causes are external to the mind responding to them, it can only infer the causes of those states and some response (aimed at minimising the degree of error in that inference, but that's not important right now). The brain is arranged in cortices each with a heirachical relation to others. What you have with the application of the term 'bad' is one end of one section of a very long collection of inference models - in this case, the end where you decide what term in your language is best used in your effort to communicate something. By necessity, the selection of this term is contextual and non-exhaustive of the mental states associated with pain, hunger etc.

So saying pain is bad is superficially nothing more than to say that "bad" is an appropriate term to use when one is experiencing pain, it's an statement about correct language use, not morality.

If you look at the issue more behaviourally, we might say that we tend to avoid 'bad' things. This gives us some observable action associated with 'bad' to take the matter outside of mere semantics. We don't have to accept a behavioural equivalent, we could associate some area(s) of the brain and use fMRI, or something. Either way, we see complications immediately, because young children do not avoid that which is painful. In fact, in cases where caregivers also produce pain, they can even, unfortunately, seek it out.

So at the very least, we have a range of physiological affects which some cortex of the brain tries to model the cause of an present to the next level cortex. At each point some interaction with the modelled causes may be initiated, there's no reason at this stage why any such response would need to be coherent with the other models.

One of these responses might be to talk to other people using the term 'bad'. There are scores of other responses not accounted for by this particular expression, many of which may also result in verbal expressions, not all of which we'd even expect to be part of some unified conception. -

apokrisis

7.8kYou seem to be reading way more into what I'm talking about than I am trying to say — Pfhorrest

apokrisis

7.8kYou seem to be reading way more into what I'm talking about than I am trying to say — Pfhorrest

I’m just interested how you think Panpsychism can work. Where’s the detail?

There's no two kinds of stuff, just events that can be interpreted two ways, both objects (matter) and subjects (mind) emerging from bundles of those interaction events (which are respectively equivalent to properties of objects or experiences of subjects, depending on which perspective you take). — Pfhorrest

How would you test this hypothesis? What perspective would reveal the experiential aspect of a stone?

This thread is about moral semantics, not ontology, and I do plan another thread on this kind of ontological topic later. — Pfhorrest

Cool. -

Kenosha Kid

3.2kThis seems to be getting at the core of the contention here. What would it mean for gods to be the phenomena underlying our morality? Would it be enough for there to simply exist gods, who issued commands? Or would those commands have to have some kind of magical imperative force that psychically inclines people to obey them? — Pfhorrest

Kenosha Kid

3.2kThis seems to be getting at the core of the contention here. What would it mean for gods to be the phenomena underlying our morality? Would it be enough for there to simply exist gods, who issued commands? Or would those commands have to have some kind of magical imperative force that psychically inclines people to obey them? — Pfhorrest

But it is of course a nonsense claim. As I said, the proposition is absurd. You may as well ask me what it would mean for morality to be made of cheese. I assume the religious answer would involve souls and divine plans somehow.

I think this line of inquiry will really help tease out what you think a claim that something is moral even means (which is the topic of this thread). Does it just mean people are inclined to act that way, so anything people tend to do definitionally is moral? Does it just mean people are inclined to approve of other people acting that way, so anything people tend to approve of definitionally is moral? Or what? — Pfhorrest

If you want to understand a bottom-up theory of morality, you have to ask what moral questions look like in such a theory, and why, and whether that corresponds to observation (empiricism). Some examples:

- is 'the cold-blooded murder of ginger people is good' true? What moral reference frame can that possibly be true in? None.

- is 'wearing a cauliflower leaf on your head on a Tuesday is good' true? Can there be a moral frame of reference for this? Yes. Is there a real person, culture, group with that perspective? No.

- is 'silence is good' true? Can there be a moral frame of reference for this? Yes. Is there a real person, culture, group with that perspective? Yes.

Reasonable questions might be: does this describe the world? are there situations where it doesn't hold? can we understand our moral ideas this way? Unreasonable questions are: who is right and wrong? what makes their good good? since these assume objectivism in a relativistic theory. -

Pfhorrest

4.6kBut it is of course a nonsense claim. As I said, the proposition is absurd. You may as well ask me what it would mean for morality to be made of cheese. I assume the religious answer would involve souls and divine plans somehow. — Kenosha Kid

Pfhorrest

4.6kBut it is of course a nonsense claim. As I said, the proposition is absurd. You may as well ask me what it would mean for morality to be made of cheese. I assume the religious answer would involve souls and divine plans somehow. — Kenosha Kid

The thing is, other than gods not existing, it seems no less absurd to me than your claims about what is “the phenomena underlying our morality”. It’s that “underlying” relationship that seems vague and unclear to me. I get the descriptive explanation of why we have certain moral intuitions, that’s perfectly clear and uncontested. What I don’t get is how you get from us having those intuitions to any manner of evaluating moral claim, UNLESS it’s simply that any way anyone is inclined to morally evaluate anything is correct simply by virtue of them being inclined to evaluate it that way.

So... if there were gods, and they did something that made us inclined to evaluate things certain ways, would that then make them the phenomena underlying our morality? Or, if they didn’t actually MAKE us inclined, but just gave orders and offered rewards and punishment, would that be enough?

- is 'the cold-blooded murder of ginger people is good' true? What moral reference frame can that possibly be true in? None. — Kenosha Kid

The Nazis though the cold blooded murder of lots of different groups was good. “Ethnic cleansing” in general is seem as good by the people who do it, hence the superlative “cleansing”. I would not at all be surprised if some society had or would support the murder of all gingers.

What makes them wrong? Or more on topic, what does it mean to say they are wrong, or that they are right?

If your meta-ethics isn’t capable of handling the true claim that Hitler did something wrong (even though he and his society thought it was right), then that looks like a pretty serious problem. -

Kenosha Kid

3.2kWhat I don’t get is how you get from us having those intuitions to any manner of evaluating moral claim, UNLESS it’s simply that any way anyone is inclined to morally evaluate anything is correct simply by virtue of them being inclined to evaluate it that way. — Pfhorrest

Kenosha Kid

3.2kWhat I don’t get is how you get from us having those intuitions to any manner of evaluating moral claim, UNLESS it’s simply that any way anyone is inclined to morally evaluate anything is correct simply by virtue of them being inclined to evaluate it that way. — Pfhorrest

As I understand it, our original conceptions of good and bad in childhood are based on what feels good abd bad. Two gamechangers are the development of empathetic responses, which I have read are astonishingly profound in many cases, and the ability to identify agency. 'It is bad for me to cut my finger' becomes 'It is bad for Alice to cut her finger' and 'Billy cutting my finger was bad' which become 'Billy cutting Alice's finger is bad' and finally 'Billy is bad for cutting Alice's finger'. It is one of many model-building capacities we simply exercise without the necessary intervention of reason.

This extends to socialisation. Punishment is an apt example: Drawing the crayon mural on mum and dad's bedroom wall felt great, but the judgement, the yelling, perhaps the hitting afterwards felt bad, so drawing on people's walls becomes bad. We're forced to identify ourselves as the agents of the bad thing, say sorry, be told we are bad. This too is added to our mental model of morality.

From that model we can draw conclusions about our behaviour and that of others. To us these seem at least approximately objective, that we have learned some things about the world. Until we meet someone with a different model.

So... if there were gods, and they did something that made us inclined to evaluate things certain ways, would that then make them the phenomena underlying our morality? Or, if they didn’t actually MAKE us inclined, but just gave orders and offered rewards and punishment, would that be enough? — Pfhorrest

I've never been religious, you're better placed than I am to describe how such people think it works. It never made much sense to me. I gather some people believe that the Bible is the source of our morals, which I assume means that pertaining to what is moral or not: the ten commandments, the teachings of Christ. The underlying reality would presumably be God's divine plan. 'Good' is then good-for-the-plan by definition. To ask whether an element of this is really 'good' just because it's part of the divine plan is erroneous, since that already assumes that good is other than that which is good in the theory entertained. This is merely a mangled way of saying that 'good' is actually something else.

If your meta-ethics isn’t capable of handling the true claim that Hitler did something wrong (even though he and his society thought it was right), then that looks like a pretty serious problem. — Pfhorrest

Again same problem. You assume there must exist objective truth values for moral claims about Hitler's actions, and measure any other moral theory with respect to that. But a different theory to yours is only obliged to account for what we see, not what you think.

In fact Hitler would be classified as antisocial. Whatever frame of reference Hitler measured 'good' in, it could not be a moral one, since it was not based on any human social capacity. (One could argue he had some sociality, given his welfare reforms, but then again not, since he sent millions of Germans to die for no reason.) Part of our sociality is how we deal with antisocial elements. In more natural circumstances, Hitler would have been attacked, exiled or murdered. His safety to proceed with exceptional antisocial ambition was a result of power. Power is a perversion of sociality, in which the better instincts and older, more social cultures are subdued, overruled, corrupted and destroyed for the good-for-me.

But that's not the real issue for you I feel. If everyone in the world ever except for Hitler and his thugs agreed that Hitler was immoral, and if the better angels of their natures were really individual empathy and drives for reciprocity and natural intolerance toward the Hitlers of the world, that would not be sufficient to capture how immoral Hitler was. What I suspect you want is not a multitude, even an infinitude, but something singular: a one off, infinitely authoritative 'Hitler was evil'. I think that's understandable because he's an extreme case, and I think that understanding what morality is at root should satisfy that: he was categorically immoral imo. -

Tarrasque

31

Tarrasque

31

As you are evidently a meticulous thinker, I will have to try my best to act as one in turn. The level of detail in your posts will delay my responses.

I say instead that moral utterances impress (and so implicitly also express; you caught the part about impression vs expression earlier?) intentions. And I say that intentions can be objectively correct or incorrect ("true" and "false" also frequently have descriptivist connotations, so I try to avoid them myself, but recognize their casual use). Both intentions and beliefs are subsets of what I call "thoughts" (as distinct from "feelings", "experiences", and other mental states), so the simplest rephrasing of the above would just be to say "John thinks ... while I think ..." instead, since the permissible/impermissible already carry subtler imperative force.

I did catch what you wrote about impression vs expression. If I understand it, it follows this neatly symmetric(quite pleasing if true!) world-to-mind vs mind-to-world dichotomy of thought that you are positing. By your account, an "impression" is a speech-act that is world-to-mind, and an "expression" is a speech-act that is mind-to-world. It is when we begin to explore the "correct/incorrect" and "true/false" distinction that I lose your train of thought. I'd like to refer back to something else you said about the importance of direction of fit: "it may be the same picture, but its intended purpose changes the criteria by which we judge it, and whether we judge the picture, or the thing it is a picture of, to be in error, should they not match."

I'd also like to borrow a quote from Wittgenstein: "The world is all that is the case." What I take it to mean is that, essentially, if one knew the conjunct of all true propositions, they would be lacking nothing in their account of reality. What it means for something to be true is that it is the case, and what it means for something to be false is that it is not the case. As you correspond "true/false" to descriptivism, I imagine you're inclined to agree. I expect that you might respond with a mirror image of this sentiment, perhaps something like "If one knew the conjunct of all correct intentions, they would be lacking nothing in their account of what-ought-to-be. What it means for something to be "correct" is that it ought to be the case, and what it means for something to be incorrect is that it ought not to be the case."

With that in mind, let's hop back to your quote. We have a picture. We wish to judge whether this picture is in error. If the picture is mind-to-world, it is of the usual descriptive sort. It is attempting to depict something factual. Note that, as described, this is strictly a two-way interaction between mind and world. In judging the picture as erroneous, we note that the idea is divergent from the content of the world. But what if the picture is world-to-mind? Now, it is of a prescriptive sort. We would expect that, given the symmetry yet distinction between these two types of claims, we would proceed through inverting the judgement used in the descriptive case. We would judge the world as erroneous for diverging from the content of the picture. I believe you say as much when you establish that the descriptive-prescriptive divide dictates "whether we judge the picture, or the thing it is a picture of, to be in error, should they not match." Again, this is a strictly two-way interaction between mind and world. What if we apply this to moral judgement?

Instead of a picture of what ought to be, we are now dealing with a claim of it: "it ought to be the case that Russia launches nukes" This is a world-to-mind judgement. Therefore, if the world does not match the mind(I imagine that in this case, that would look like "Russia is not in fact launching nukes"), we judge the world to be in error. This, on its own, entails relativist conclusions. This presents a problem. I expect that you would respond to this problem by claiming that "it ought to be the case that Russia launches nukes" is an intention uttered in error, since it ought not to be the case that Russia launches nukes. At this point, mind-to-world can no longer be considered symmetrical to world-to-mind. Instead of the two-way relation between world and mind that we explicitly find in the mind-to-world case, we are forced to introduce some further arbitration to account for the fact that even in a world-to-mind judgement, the mind can be mistaken in some further way besides simply not matching the world. As opposed to mind-world, we have something like world-mind-standard. You might accept this asymmetry, but it harms the parsimony of your theory to do so. Of course, I would avoid this issue by wholeheartedly accepting that moral states of affairs exist, and utterances concerning them are beliefs which can be true or false in the regular way.

So in your modus ponens, the logical relationship is actually between "stealing happening" and "getting your little brother to steal": getting your little brother to steal entails stealing happening. So if it-ought-to-be-the-case-that-there-is(not(stealing happening)), and (getting your little brother to steal) entails (stealing happening), then it-ought-to-be-the-case-that-there-is(not(getting your little brother to steal)).

You can replace it-ought-to-be-the-case-that-there-is with it-is-the-case-that-that-there-is and you get the same logical relations, just with descriptive force instead of prescriptive force.

Sure, you can explain that modus ponens that way. I actually found this response quite persuasive on the first reading, and thought I might have to abandon this line of analysis. On further reflection, I found your explanation lacking when applied to other moral modus ponens. First, let me structure your account of the logical relation in argumentative form:

P1. It ought-to-be-the-case-that-there-is(not(stealing happening))

P2. If (getting your little brother to steal) then (stealing happening)

C. It ought-to-be-the-case-that-there-is(not(getting your little brother to steal))

It certainly seems that if one were to accept P1 and P2, yet reject C, they would be succumbing to a logical failing. This accounts for the logical force of modus ponens. It is also intuitive that yes, if I get my little brother to steal, stealing is happening! Your alternative P2 seems synonymous with my original P2. In that sense, it can be argued to be semantically identical to the original syllogism. That is why I considered your response sufficient to resolve that particular modus ponens. However:

P1. Stealing is wrong

P2. If stealing is wrong, then cheating on a significant other is wrong

C. Cheating on a significant other is wrong

Let's translate into your proposed logical language.

P1*. It ought-to-be-the-case-that-there-is(not(cheating happening))

P2*. If (cheating happening) then (stealing happening)

C*. It ought-to-be-the-case-that-there-is(not(stealing happening))

Something isn't right here. P2 is translated incorrectly. The meaning of "If stealing is wrong, then cheating on a significant other is wrong" is totally different than the meaning of "If (cheating happening) then (stealing happening)." The relation that you originally proposed(getting my little brother to steal entails stealing happening) does not accurately explain WHY moral modus ponens is valid. Let's translate P2 more faithfully.

P2**. If it ought-to-be-the-case-that-there-is(not(cheating happening)), then (it ought-to-be-the-case-that-there-is(not(stealing happening))

After this translation, I'm unsure why you'd have to invent a different logic for dealing with prescriptive claims at all. "Stealing is wrong" and "It ought not to be the case that there is stealing happening" are identical claims by your view anyhow. In response to the bolded text, I concur that we can treat "is" and "ought" interchangeably in syllogisms as far as logical validity is concerned. Where we diverge, however, is that you seem to think that this is in every case meaningful. I believe that many, if not most atomic sentences produced by swapping "is" with "ought"("the sky ought to be blue," "the earth ought to be round," "a certain star a million light years away ought to be mostly hydrogen" "a triangle ought to have three sides") are nonsense in normative terms.

I see prudential oughts as boiling down to a kind of moral ought. Taking care of yourself is a kind of moral good -- not necessarily an obligatory one, but still a moral one even if only supererogatory, you matter just like everybody else matters -- and instrumentally seeing to moral ends is still a kind of moral good. So you should stop smoking because if you don't you'll probably suffer and die, and people suffering and dying is bad.

This satisfies me. Well put. If there are in fact any prudential reasons that do not collapse to moral reasons, I can't think of one right now.

Rational "oughts" I think can be better rephrased descriptively. "If you proportion your belief to the evidence your belief is more likely to be accurate." You might ask "but should beliefs be accurate?" and the answer to that is a trivial yes, because believing something just is thinking it's an accurate description of reality. If you didn't care to have an accurate description of reality, you wouldn't bother forming beliefs.

This, I find much more problematic. You could rephrase moral oughts descriptively in the same way: "If you don't lie to people, you are more likely to be morally correct." The fact remains that rational normativity is used extensively in language, and not just by term-confused laypeople. We tend to believe that people ought to be rational - that they ought to aim to believe only true things, they ought not to hold obviously contradictory beliefs, they ought to afford greater consideration to good reasons rather than bad ones. You might suggest that these collapse to moral oughts, holding that we only value rational norms because to forsake them would result in great unpleasantness for us, or something like that. I think this is defensible, but dubious. I suggest the opposite - that what is moral is merely a subset of what is rational. When I consider your arguments for your position, I am considering reasons. I might have good moral reason to agree with everything you say and shower you with compliments. This would certainly make you happy, if you believed it to be sincere. It may be supererogatory, but if all reasons are moral reasons, what does it really mean for something to be supererogatory?(I saw your chart, but that raised more questions than it answered. Why is "bad" contained within "supererogatory?") The thing that I have the most moral reason to do would always be the thing that I have the most overall reason to do, by definition. Why do people disagree at all in cases when agreement would result in a morally preferable state of affairs? Perhaps they are responding to reasons which are not moral in nature, and indeed may be stronger than whatever small moral reason they have to abandon their argument and agree.

For instance, take this principle: "If another person is meaningfully disagreeing with you, and you know that they cannot be convinced of your position, you ought to concede." Morally, this is justifiable. Continued disagreement without even the possibility of agreement is pointless. It serves only to create strife and tension, which is not a preferable moral state of affairs. Would it not be advisable to change your beliefs and eliminate this tension? Surely you have no moral reason to choose a true belief over a false one, unless holding this false belief itself somehow harms people. This could even be avoided. I could become a "round-earth constructivist," believing something like "the earth is truly flat, but we must act as though it is round for the best results." I could adopt this belief because I have good moral reason to do so: dissolving tension with flat-earthers who cannot be convinced. Is a principle like this the one you have the most reason to follow? Is concession, changing your beliefs when you are certain your interlocutor will not change theirs, the thing you have the most reason to do?

beliefs are to be judged by appeal to the senses, everyone's senses in all circumstances if they are to be judged objectively, and intentions are to be judged by appeal to the appetites, everyone's appetites in all circumstances if they are to be judged objectively.

But yet, everybody's senses in all circumstances could still lead to something false. There might be things which are true of the world and yet empirically unverifiable, even in principle, like the existence of a god. As an epistemological verificationist principle, I suppose this is really as good as it gets. But as a principle for defining what is actually true/false, correct/incorrect, this lacks in the same way that a traditional "ideal rational observer" account does.

They are instead pushing a considered thought about how everyone should think things ought to be, in the same way that descriptive statements are pushing a considered thought about how everyone should think things are.

Woah, woah. Descriptive statements are pushing a considered thought about how everyone should think things are? That itself is prescriptive! I also think it's inaccurate. Consider a color judgement. I have a degree of red-green colorblindness. If I make a descriptive claim such as "this chair is brown," I would sure hope I'm not implying that everybody else ought to see the chair the way I do! I am merely reporting how I observe the chair to be. -

creativesoul

12.2kA sound argument. One that makes valid inferences from true premises. — Pfhorrest

Soundness alone is sorely inadequate. Not all sound arguments are on equal justificatory footing. -

Isaac

10.3kAs I understand it, our original conceptions of good and bad in childhood are based on what feels good abd bad. Two gamechangers are the development of empathetic responses, which I have read are astonishingly profound in many cases, and the ability to identify agency. 'It is bad for me to cut my finger' becomes 'It is bad for Alice to cut her finger' and 'Billy cutting my finger was bad' which become 'Billy cutting Alice's finger is bad' and finally 'Billy is bad for cutting Alice's finger'. It is one of many model-building capacities we simply exercise without the necessary intervention of reason.

Isaac

10.3kAs I understand it, our original conceptions of good and bad in childhood are based on what feels good abd bad. Two gamechangers are the development of empathetic responses, which I have read are astonishingly profound in many cases, and the ability to identify agency. 'It is bad for me to cut my finger' becomes 'It is bad for Alice to cut her finger' and 'Billy cutting my finger was bad' which become 'Billy cutting Alice's finger is bad' and finally 'Billy is bad for cutting Alice's finger'. It is one of many model-building capacities we simply exercise without the necessary intervention of reason.

This extends to socialisation. Punishment is an apt example: Drawing the crayon mural on mum and dad's bedroom wall felt great, but the judgement, the yelling, perhaps the hitting afterwards felt bad, so drawing on people's walls becomes bad. We're forced to identify ourselves as the agents of the bad thing, say sorry, be told we are bad. This too is added to our mental model of morality.

From that model we can draw conclusions about our behaviour and that of others. To us these seem at least approximately objective, that we have learned some things about the world. Until we meet someone with a different model. — Kenosha Kid

Just out of interest, what sources are you relying on for this take? -

Kenosha Kid

3.2kJust out of interest, what sources are you relying on for this take? — Isaac

Kenosha Kid

3.2kJust out of interest, what sources are you relying on for this take? — Isaac

I didn't note sources, sorry, but I'll do what I can.

As I understand it, our original conceptions of good and bad in childhood are based on what feels good abd bad. Two gamechangers are the development of empathetic responses, which I have read are astonishingly profound in many cases, and the ability to identify agency. 'It is bad for me to cut my finger' becomes 'It is bad for Alice to cut her finger' and 'Billy cutting my finger was bad' which become 'Billy cutting Alice's finger is bad' and finally 'Billy is bad for cutting Alice's finger'. It is one of many model-building capacities we simply exercise without the necessary intervention of reason. — Kenosha Kid

So the first part of this is, I think, uncontroversial: children show signs of distress well before they show signs of responding to others' distress. [There are exceptions. Babies react with distress to the sound of other babies' distress. It's worth remembering that some phenomena, like babies crying, are inevitable and can therefore be selected for, while others, such as Billy pulling Alice's hair, are not.] The magnitude of this development of what amounts to the total of cognitive and emotional empathy, as well as the development of empathetic responses, are summarised here: http://local.psy.miami.edu/faculty/dmessinger/c_c/rsrcs/rdgs/emot/McDonald-Messinger_Empathy%20Development.pdf which has a good starting-point bibliography for more reading.

In terms of how children build social models of morality, you can take a look at social learning theory, such as Aronfreed J. Conduct and Conscience or Rosenhan D. Some origins of concern for others (1969). Old stuff, but still regularly cited. (Probably best to look at review papers that cite those.)

This extends to socialisation. Punishment is an apt example: Drawing the crayon mural on mum and dad's bedroom wall felt great, but the judgement, the yelling, perhaps the hitting afterwards felt bad, so drawing on people's walls becomes bad. We're forced to identify ourselves as the agents of the bad thing, say sorry, be told we are bad. This too is added to our mental model of morality. — Kenosha Kid

So this is stage 1 of Kohlberg's moral development schema: pre-conventional morality, in which moral rules are implemented pragmatically to avoid punishment. (Obviously moral rules can also be implemented to increase rewards, however, as Daniel Kahneman has pointed out in his psychology of risk work, we are much more risk-averse than reward-oriented.) Kohlberg's model is quite old, but it's still relevant, i.e. still cited across the board in papers on child development of morality. It's also very broad, so more modern research (such as that above) should hold more weight. -

BitconnectCarlos

2.8k

BitconnectCarlos

2.8k

As a child, pain is objectively bad. — Outlander

When I was a kid I remember falling on my bike a few times - probably from going too fast - and scraping my knee. Pain can help someone learn their limitations, and not just for children. By and large though these things - suffering, starvation, abuse - definitely seem bad. But there are cases where due to someone going through these things they came out a better, more mature person. -

Isaac

10.3k

Isaac

10.3k

Thanks. I think you'd enjoy some of the more modern works on child development. There's been a considerable amount of progress since the likes of Rosenhan and Kohlberg, much of it up-turning the older models quite radically. Alison Gopnick has written a few good books 'The Scientist in the Crib' and 'The Philosophical Baby' are the best, I think. Alternatively I can give you some paper recommendations if you prefer the original sources. Either way, I think you'll find the developments interesting.

If, on the other hand, you've already read all that and just disagree with it, then ignore the above and I'd love to hear your thoughts on it. It's very hard from a few posts to judge someone's investment in a topic. One doesn't want to seem unhelpful, but on the other side one need avoid being condescending - apologies if I miss the mark. -

Kenosha Kid

3.2kThanks. I think you'd enjoy some of the more modern works on child development. There's been a considerable amount of progress since the likes of Rosenhan and Kohlberg, much of it up-turning the older models quite radically. Alison Gopnick has written a few good books 'The Scientist in the Crib' and 'The Philosophical Baby' are the best, I think. Alternatively I can give you some paper recommendations if you prefer the original sources. Either way, I think you'll find the developments interesting. — Isaac

Kenosha Kid

3.2kThanks. I think you'd enjoy some of the more modern works on child development. There's been a considerable amount of progress since the likes of Rosenhan and Kohlberg, much of it up-turning the older models quite radically. Alison Gopnick has written a few good books 'The Scientist in the Crib' and 'The Philosophical Baby' are the best, I think. Alternatively I can give you some paper recommendations if you prefer the original sources. Either way, I think you'll find the developments interesting. — Isaac

Yeah I've read some of Gopnik and Meltzoff. The Scientist in the Crib was a recommendation I was going to give you, but I find books aren't usually very helpful in these sorts of discussions. Review articles are best I think, as they both summarise and cite the broadest range of research. Both Gopnik and Meltzoff have done work on how children develop causal inferences and how they construct the sorts of cognitive structures I was talking about, some of which is summarised in that first link, which I recommended more for its bibliography.

I'm not aware of any radical overthrow of Kohlberg's stages themselves. His interpretations are old hat, but the empirical data and the broad structure and concepts of his theory are still cited regularly today. It is, after all, just Pavlovian learning, something even babies are capable of, and which will always precede any learning based on later psychological development. But if you want a better citation, there's Schultz, Wright & Schleifer (1986) whose experiments also showed that knowledge that X leads to punishment precedes knowledge that X is immoral. -

Isaac

10.3kI'm not aware of any radical overthrow of Kohlberg's stages themselves. His interpretations are old hat, but the empirical data and the broad structure and concepts of his theory are still cited regularly today. It is, after all, just Pavlovian learning, something even babies are capable of, and which will always precede any learning based on later psychological development. — Kenosha Kid

Isaac

10.3kI'm not aware of any radical overthrow of Kohlberg's stages themselves. His interpretations are old hat, but the empirical data and the broad structure and concepts of his theory are still cited regularly today. It is, after all, just Pavlovian learning, something even babies are capable of, and which will always precede any learning based on later psychological development. — Kenosha Kid

Most of Gopnik's work, together with say, Tania Singer's and Karen Wynn is about overthrowing Kohlberg's stages. Newborn babies show empathy, one year olds show signs of Theory of Mind etc... I'd be very interested to hear what you got out of those advances if not the up-turning of Kohlberg, always interesting to hear a different perspective. I'm not sure this is the place for it though, I've already had one slapped wrist for derailing the thread, I don't want to incur another. -

Enrique

845I’m just interested how you think Panpsychism can work. Where’s the detail? — apokrisis

Enrique

845I’m just interested how you think Panpsychism can work. Where’s the detail? — apokrisis

To step in and quickly clarify the science of panpsychism, I've got a theory as to how it probably works that I posted as a brief essay on this site, its the OP of the thread: Qualia and Quantum Mechanics, the Reality Possibly. Not at all proven yet, but is based on some solid research and in my opinion very unlikely to be inaccurate in the essentials. How plausible do you find it? -

Kenosha Kid

3.2kMost of Gopnik's work, together with say, Tania Singer's and Karen Wynn is about overthrowing Kohlberg's stages. — Isaac

Kenosha Kid

3.2kMost of Gopnik's work, together with say, Tania Singer's and Karen Wynn is about overthrowing Kohlberg's stages. — Isaac

Terrible job done then, since Kohlberg is still cited regularly to this day and his terminology (e.g. "post-conventional") is well and truly in the mainstream. Variations on the same theme still go strong, through Hoffman's four-stage system which also has full empathetic development at adolescence, to Commons & Wolfsont's seven stages which more or less maps to Kohlberg's but with the emphasis on development of empathetic capacity rather than moral practise, still identifying the same key stages of non-systematic efforts to help, interpersonal development, and reciprocal altruism. Details have changed, much has been filled in, but at the end of the day data is data: babies do not slop out as fully formed moral agents; they arrive at that in stages.

Newborn babies show empathy, one year olds show signs of Theory of Mind etc... — Isaac

Yes, I mentioned the findings about babies to you already above. In the literature I've read, these are considered precursors to empathetic reactions: they are not the complete hardware and software ready and rolled out day one, and they're certainly not considered fully formed moral models. I don't think any of that is too surprising: we are biologically wired for empathy, altruism and detecting causality. It would be weird if child development went: nothing, nothing, nothing, nothing, EVERYTHING! -

apokrisis

7.8kI won’t derail here. But I might reply in that thread. A quick skim already brings up the fact that the kind of organic chemistry scale quantum coherence you talk about is indeed why I now argue so forcefully for pansemiosis rather than Panpsychism. Biophysics demonstrates the true generality of the semiotic perspective.

apokrisis

7.8kI won’t derail here. But I might reply in that thread. A quick skim already brings up the fact that the kind of organic chemistry scale quantum coherence you talk about is indeed why I now argue so forcefully for pansemiosis rather than Panpsychism. Biophysics demonstrates the true generality of the semiotic perspective.

See https://thephilosophyforum.com/discussion/comment/105999 -

Pfhorrest

4.6kAs you are evidently a meticulous thinker, I will have to try my best to act as one in turn. The level of detail in your posts will delay my responses. — Tarrasque

Pfhorrest

4.6kAs you are evidently a meticulous thinker, I will have to try my best to act as one in turn. The level of detail in your posts will delay my responses. — Tarrasque

Thank you! And no worries at all about delay. Finding time to do anything on my own (i.e. not hanging out with gf who is locked down with me) is increasingly difficult for me these days myself.

By your account, an "impression" is a speech-act that is world-to-mind, and an "expression" is a speech-act that is mind-to-world. — Tarrasque

Nope! Two different orthogonal divides, the distinction between which is critical to my account. Direction of fit is about the kind of opinion (descriptive or prescriptive), and impression vs expression is about what you’re doing with that opinion relative to someone else (just showing them what opinion is in your mind, or trying to change the opinion in their mind). You can impress or express either kind of opinion, descriptive or prescriptive. If anything, expression is more description-like because it merely shows what your opinions are (so is like describing your opinions), while impression is more prescription-like because it tells someone to have certain opinions (so is like prescribing your opinions). But they are still orthogonal: you can express your beliefs, impress your beliefs, express your intentions, or impress your intentions.

It is when we begin to explore the "correct/incorrect" and "true/false" distinction that I lose your train of thought. I'd like to refer back to something else you said about the importance of direction of fit: "it may be the same picture, but its intended purpose changes the criteria by which we judge it, and whether we judge the picture, or the thing it is a picture of, to be in error, should they not match."

I'd also like to borrow a quote from Wittgenstein: "The world is all that is the case." What I take it to mean is that, essentially, if one knew the conjunct of all true propositions, they would be lacking nothing in their account of reality. What it means for something to be true is that it is the case, and what it means for something to be false is that it is not the case. As you correspond "true/false" to descriptivism, I imagine you're inclined to agree. I expect that you might respond with a mirror image of this sentiment, perhaps something like "If one knew the conjunct of all correct intentions, they would be lacking nothing in their account of what-ought-to-be. What it means for something to be "correct" is that it ought to be the case, and what it means for something to be incorrect is that it ought not to be the case." — Tarrasque

Very nearly! If true/false are being used in the narrower descriptive sense then I agree with Wittgenstein there. “Correct/incorrect” I use as broader terms that don’t have that descriptive connotation, so they can apply to either beliefs or intentions. A correct belief is a true belief. And a correct intention is a good intention. (In looser language that e.g. a Kantian might use, what I call a “good intention” would be called a “true moral belief”: a correct cognitive opinion with world-to-mind fit). The conjunct of all correct (good) intentions would be a complete account of morality, in the sense of what-ought-to-be. And what it means for something to be “good” is that it ought to be the case, and “bad” vice versa.

With that in mind, let's hop back to your quote. We have a picture. We wish to judge whether this picture is in error. If the picture is mind-to-world, it is of the usual descriptive sort. It is attempting to depict something factual. Note that, as described, this is strictly a two-way interaction between mind and world. In judging the picture as erroneous, we note that the idea is divergent from the content of the world. But what if the picture is world-to-mind? Now, it is of a prescriptive sort. We would expect that, given the symmetry yet distinction between these two types of claims, we would proceed through inverting the judgement used in the descriptive case. We would judge the world as erroneous for diverging from the content of the picture. I believe you say as much when you establish that the descriptive-prescriptive divide dictates "whether we judge the picture, or the thing it is a picture of, to be in error, should they not match." Again, this is a strictly two-way interaction between mind and world. What if we apply this to moral judgement?

Instead of a picture of what ought to be, we are now dealing with a claim of it: "it ought to be the case that Russia launches nukes" This is a world-to-mind judgement. Therefore, if the world does not match the mind(I imagine that in this case, that would look like "Russia is not in fact launching nukes"), we judge the world to be in error. This, on its own, entails relativist conclusions. This presents a problem. I expect that you would respond to this problem by claiming that "it ought to be the case that Russia launches nukes" is an intention uttered in error, since it ought not to be the case that Russia launches nukes. At this point, mind-to-world can no longer be considered symmetrical to world-to-mind. Instead of the two-way relation between world and mind that we explicitly find in the mind-to-world case, we are forced to introduce some further arbitration to account for the fact that even in a world-to-mind judgement, the mind can be mistaken in some further way besides simply not matching the world. As opposed to mind-world, we have something like world-mind-standard. You might accept this asymmetry, but it harms the parsimony of your theory to do so. Of course, I would avoid this issue by wholeheartedly accepting that moral states of affairs exist, and utterances concerning them are beliefs which can be true or false in the regular way. — Tarrasque

I must admit I have noted this apparent asymmetry before and struggled to reckon with it. It makes me feel like there is something I haven't fully developed right. When it comes to my approaches to assessing the correctness of either beliefs or intentions, I do end up with a nice symmetry again, but it feels like some bridge between the symmetry of meanings and the symmetry of assessment is missing, for the reasons you state. So I'm glad we're talking about it, because this is the kind of situation where I usually come up with newer, better thoughts.

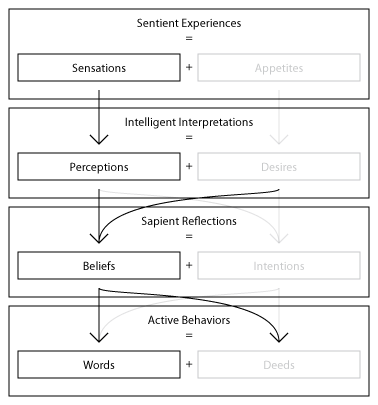

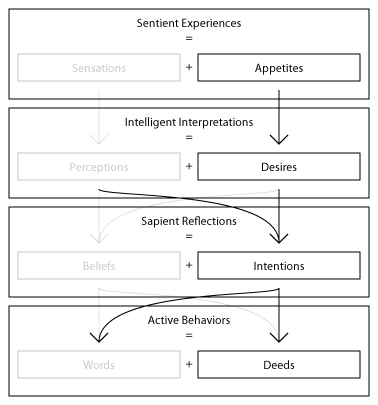

The symmetry I end up with for assessing the correctness of either kind of opinion is checking the opinion against experiences, where experiences come in different varieties that carry their own direction of fit: experiences with mind-to-world fit are sensations (like sight and sound), and experiences with world-to-mind fit are appetites (like pain and hunger). In both cases, assessment of the objective correctness of an opinion needs to account for not just the experiences you are actually having right here and now, but all the experiences anyone could have in any context.

I think perhaps the missing bridge that avoids the asymmetry you note -- and this is just me thinking on the fly here, not recounting thoughts I've already had before, so thank you again for prompting some new thought -- is that direction of fit needs to be reckoned not so much as a relationship between the mind and the world, as it usually is, but rather as a relationship of these different descriptive and prescriptive models to our overall function from our experiences to our behavior. We don't have direct access to the world, all we have is the experience of our interactions with the world, what it does to us and what we do to it.

Being interactions between ourselves and the world, our experiences of either kind are about both ourselves and the world: sensations tell us about how things look to beings like us in certain circumstances, appetites tell us about how things feel to beings like us in certain circumstances. The direction of fit is more between those self-regarding and world-regarding aspects of the experience, internal to the experience, than between the mind and the world itself.

To most beings, the "is" and "ought" aspects of experience are completely intermixed: the world does something to it and that immediately prompts it to do something in response. Sentient beings, on the other hand, differentiate our experiences into those to be used to build a "still life" (mind-to-world-fit picture), our sensations, and those used to build a "blueprint" (world-to-mind-fit picture), our appetites. Sapient beings, furthermore, reflect upon those pictures and assess whether they have correctly constructed them.

We then behave in such a way as to bridge the difference between the two images we've constructed: to change things from the "still life" (mind-to-world image) to the "blueprint" (world-to-mind image). The two images can thus be defined in terms of their role in driving our behavior: one is the "from" side of the change we're making, and the other is the "to" side.

This doesn't fall into relativism because in principle both of those images can be constructed in an objective manner, taking into account not just the experiences you are actually having right here and now, but all the experiences anyone could have in any context.

P2. If stealing is wrong, then cheating on a significant other is wrong — Tarrasque

This doesn't seem to be a logically necessary premise in the same was as "if stealing is wrong, getting your little brother to steal is wrong". So it makes sense that you wouldn't reconstruct that in the same way as the brother implication, as "(stealing) implies (cheating)", because that's incorrect; there could be stealing and not cheating. (BTW I think you reversed those a couple times in your post, not that it makes a big difference). Your reconstruction as -- to use my shorter nomenclature from earlier -- "be(not(stealing)) implies be(not(cheating))" is thus a better reconstruction than "steaming implies cheating". But that is then a questionable premise because it's not a logical necessity, as you're just saying:

be(not(cheating)) or not(be(not(stealing)))

or equivalently:

not(be(not(stealing)) and not(be(not(cheating))))

because material implication is counterintuitive like that, unlike logical implication.

(I saw your chart, but that raised more questions than it answered. Why is "bad" contained within "supererogatory?") — Tarrasque

For the same reason that "false" is contained within "contingent": supererogatory = not-obligatory, and all bad things are not-obligatory, just like contingent = not-necessary, and all false things are not-necessary. (There are some things that are necessarily false, but that just means impossible; likewise, things that are "obligatorily bad", so bad you are obliged not to do them, are just impermissible).

But yet, everybody's senses in all circumstances could still lead to something false. There might be things which are true of the world and yet empirically unverifiable, even in principle, like the existence of a god. — Tarrasque

I disagree. When it comes to the limited domain of descriptive propositions, I agree completely with the verificationist theory of truth: a claim that something is true of the world yet has absolutely no empirical import is literally meaningless nonsense. If something like gods can really be said to exist, there must be something observable about them.

Woah, woah. Descriptive statements are pushing a considered thought about how everyone should think things are? That itself is prescriptive! — Tarrasque

This mostly boils down to the difference between impression/expression and prescription/description clarified at the start of this post. That "should" there is more an "impressive should" than a "prescriptive should"; natural language can be sloppy, again.

But in response to both this and the large part about the normativity of reasons generally that I didn't quote earlier, I now remember that I have in other contexts thought about normativity as it relates to thought more generally, not just about prescriptive thoughts like intentions, in my work on philosophy of mind and will.

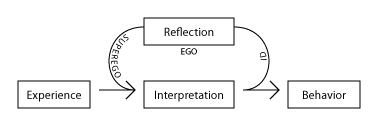

Basically, the reflexive process of self-judgement involved in forming "thoughts" (beliefs and intentions) involves casting both our descriptive and prescriptive judgements upon either our descriptive or our prescriptive judgements. When we (descriptively) look at what we perceive (descriptively) and judge (prescriptively) that it is the correct thing to perceive, that constitutes a (descriptive) belief. When we (descriptively) look at what we desire (prescriptively) and judge (prescriptively) that it is the correct thing to desire, that constitutes a (prescriptive) intention.

So you're right, there is normativity/prescriptivity involved in reasoning generally, that I was forgetting about earlier.

The prescriptivity involved there is still ultimately the same kind as moral prescriptivity, though. It's basically a case of considering what the proper function of a human mind is -- proper as in good, good as in prudential good, which we've already established boils down to moral good -- and then looking upon yourself in the third person, so to speak, and thinking "Hey, there's a mind! Is it functioning properly? No no, it should be perceiving like this and desiring like that instead..." It's self-parenting. Parents teach their kids how to think, both in terms of figuring out what is true and in terms of figuring out what is good, for the moral good of those kids, and everyone they'll have an impact on, right? Likewise, making sure we ourselves are thinking correctly is ultimately for a moral good too.

I also think it's inaccurate. Consider a color judgement. I have a degree of red-green colorblindness. If I make a descriptive claim such as "this chair is brown," I would sure hope I'm not implying that everybody else ought to see the chair the way I do! I am merely reporting how I observe the chair to be. — Tarrasque

That would be an expression, not an impression, as clarified at the start of this post.

Thank you for this engaging conversation! No rush on your response, it'll take me a while to get to it anyway. -

Isaac

10.3k

Isaac

10.3k

Both Hoffman and Commons published over two decades ago. A lot has changed since then, and Kohlberg's methodology would laughed out of the office these days if it were a new research proposal. Psychology is not like other sciences where there's a clear set of theories which match experimental data and a clear set which don't. A lot of interpretation relies heavily of the model framework through which it's analysed. Fo this reason you see a lot of psychology textbooks and courses still citing older models in much the same way philosophy papers will track the history of an idea. It doesn't mean they think those models are still the best approach, it's just that it's important to track how we got to where we are so that the assumptions are obvious. I can guarantee you that neither Kohlberg, Hoffman nor Commons will be taught on a modern Child Development degree without detailing the extent to which their assumptions have been shown to wrong.

It would be weird if child development went: nothing, nothing, nothing, nothing, EVERYTHING! — Kenosha Kid

Exactly. So weird in fact, that no-one has even bothered testing such a model. So the entire debate is about when and how developmental stages take place. Kohlberg got the when and the how wrong. There mere fact that development takes place in stages was not Kohlberg's invention, nor even Piaget's. No one ever even questioned that assumption, so it's not true to say their work is still relevant simply because people still talk about staged development. The issues are the rate of progress, the path taken and the influences effecting that progress.

Your field is Physics I believe. Imagine if I cited some old ideas about black holes or quantum mechanics and you said "Oh there's been a lot of new developments since then", citing the latest research and I just said "Oh yeah, but these old guys are still cited so your new lot haven't done a very good job have they?". I think we both know that's not how science works.

Welcome to The Philosophy Forum!

Get involved in philosophical discussions about knowledge, truth, language, consciousness, science, politics, religion, logic and mathematics, art, history, and lots more. No ads, no clutter, and very little agreement — just fascinating conversations.

Categories

- Guest category

- Phil. Writing Challenge - June 2025

- The Lounge

- General Philosophy

- Metaphysics & Epistemology

- Philosophy of Mind

- Ethics

- Political Philosophy

- Philosophy of Art

- Logic & Philosophy of Mathematics

- Philosophy of Religion

- Philosophy of Science

- Philosophy of Language

- Interesting Stuff

- Politics and Current Affairs

- Humanities and Social Sciences

- Science and Technology

- Non-English Discussion

- German Discussion

- Spanish Discussion

- Learning Centre

- Resources

- Books and Papers

- Reading groups

- Questions

- Guest Speakers

- David Pearce

- Massimo Pigliucci

- Debates

- Debate Proposals

- Debate Discussion

- Feedback

- Article submissions

- About TPF

- Help

More Discussions

- Other sites we like

- Social media

- Terms of Service

- Sign In

- Created with PlushForums

- © 2026 The Philosophy Forum