-

Isaac

10.3kWe haven't even resolved the dispute about vaccines, or the dispute about flat earth. — Tarrasque

Isaac

10.3kWe haven't even resolved the dispute about vaccines, or the dispute about flat earth. — Tarrasque

Then whence the notion "It is not an impasse like you would expect if people's disagreements were just brute expressions."? It seems like an impasse, and you were previously imploring that we treat things the way they seem to be until we have good reason to believe otherwise.

These well-considered decisions are often better decisions. — Tarrasque

Do you have any reason to believe this? -

Tarrasque

31

Tarrasque

31

Then whence the notion "It is not an impasse like you would expect if people's disagreements were just brute expressions."? It seems like an impasse, and you were previously imploring that we treat things the way they seem to be until we have good reason to believe otherwise.

Perhaps I should have said moral disagreement is not at more of an impasse than disagreement about things we all agree are matters of fact. On the individual level, views on issues like abortion are changed. There are also people at metaethical impasses, but this alone does not push us to conclude that discussion about metaethics is noncognitive. If you thought this, you wouldn't talk about "reasons for believing expressivism" at all. "There are pages full of reasons for expressivism" would just be you expressing "Woo, expressivism!"

Do you have any reason to believe this?

Do I have any reason to believe that well-considered decisions are often better decisions?

Well, a reason is a consideration in favor of X. If, after deliberation, I conclude that X is what has the most/strongest considerations in favor of it, this is what I think I have the most reason to do. This means that I think it's the best thing to do. You're asking me, right now, to consider my reasons for a belief. You think I've reached the wrong conclusion about what the most reasonable thing to believe is, right? You implore me to review my beliefs by exposing them to compelling arguments. Are more well-reasoned arguments likely better arguments? Are well-reasoned positions often better positions? If so, why not believe that well-reasoned decisions are often better decisions? -

Isaac

10.3kI should have said moral disagreement is not at more of an impasse than disagreement about things we all agree are matters of fact. — Tarrasque

Isaac

10.3kI should have said moral disagreement is not at more of an impasse than disagreement about things we all agree are matters of fact. — Tarrasque

Really? If that's how you see it I'm not going to argue with you about it, but it seems odd to me. I can't think if a single moral fact that everyone agrees on, and not many that are agreed even by a large majority. I can say, however, that virtually everyone in the world agrees on the physical properties of tables, or the physical functioning of a cup. That solid things cannot pass through other solid things, that large objects do not fit inside smaller ones...etc.

views on issues like abortion are changed. — Tarrasque

Indeed, a fact that in no way tells us the method by which they are changed.

There are also people at metaethical impasses, but this alone does not push us to conclude that discussion about metaethics is noncognitive. If you thought this, you wouldn't talk about "reasons for believing expressivism" at all. "There are pages full of reasons for expressivism" would just be you expressing "Woo, expressivism!" — Tarrasque

You're mistaking "pages full of reasons" with "pages full of reasons which I agree with". That's the entire point I'm making. Both you (and Pfhorrest earlier) seemed to be implying that reasons (the mere existence of them) could be somehow put into some global accounting system and out pops the 'right' way of looking at things. By saying that expressivist philosophers have "pages of reasons" I'm just trying to show that their mere existence doesn't get us anywhere.

All of our epistemic peers have reasons which seem coherent and logical to them. The activity we're involved in is choosing between them. We can't cite the existence of reasons as an explanation of our choice (all options have those). That's all I meant. I'm not advocating expressivism.

You're asking me, right now, to consider my reasons for a belief. You think I've reached the wrong conclusion about what the most reasonable thing to believe is, right? You implore me to review my beliefs by exposing them to compelling arguments. Are more well-reasoned arguments likely better arguments? Are well-reasoned positions often better positions? — Tarrasque

I'm not imploring you to think anything, nor do I think you've reached the wrong conclusion about what the most reasonable thing to believe is. I'm interested in how you come to believe (and defend) whatever it is you believe. To answer your question though - I think more well-reasoned arguments are better arguments by definition. The measure we usually use to determine 'better' when it come to arguments is the the quality of the reasoning (a subjective judgement, I might add, but nonetheless the case). Decisions, however, are not usually judged 'better' on the strength of their reasons, they're usually judged on the evaluation of their outcome, so the two are different. It's like saying "tasty cakes are usually better cakes, so why not believe tasty computers are better computers". -

Tarrasque

31

Tarrasque

31

I can't think if a single moral fact that everyone agrees on, and not many that are agreed even by a large majority. I can say, however, that virtually everyone in the world agrees on the physical properties of tables, or the physical functioning of a cup. That solid things cannot pass through other solid things, that large objects do not fit inside smaller ones...etc.

You raise a good point. There are facts about physical reality that are extremely basic, agreed upon by practically everyone. There are also physical matters-of-fact that are much more contentious. Likewise, there are moral facts that enjoy the agreement of a vast majority: that torturing someone for absolutely no reason other than personal pleasure is wrong, for instance, or that committing genocide is worse than donating to charity. The consensus may not be as high as our most basic physical intuitions, but I'd bet you it's close.

I'm interested in how you come to believe (and defend) whatever it is you believe.

What are some arguments against, say, cognitivism, that you'd like to see me respond to?

To answer your question though - I think more well-reasoned arguments are better arguments by definition. The measure we usually use to determine 'better' when it come to arguments is the the quality of the reasoning (a subjective judgement, I might add, but nonetheless the case).

Funnily enough, I don't think that quality of reasoning is subjective.

Decisions, however, are not usually judged 'better' on the strength of their reasons, they're usually judged on the evaluation of their outcome, so the two are different.

Evaluating the outcome of a decision is reasoning about it.

Buying a thousand lottery tickets is a poorly reasoned decision. It is a gamble which has an incredibly small chance of resulting in your desired outcome. Perhaps one of your tickets is a winner. You win more than enough to compensate what you spent on tickets. Do we judge your decision as good, based on the outcome? Or was it poor, based on the reasoning? Would you repeat your decision if you had the opportunity to buy a thousand tickets for the next lottery? Would you recommend that your friends and family do the same? -

Isaac

10.3kthere are moral facts that enjoy the agreement of a vast majority: that torturing someone for absolutely no reason other than personal pleasure is wrong, for instance, or that committing genocide is worse than donating to charity. — Tarrasque

Isaac

10.3kthere are moral facts that enjoy the agreement of a vast majority: that torturing someone for absolutely no reason other than personal pleasure is wrong, for instance, or that committing genocide is worse than donating to charity. — Tarrasque

I don't see any widespread agreement on those matters. Torturing someone for no reason, is just definitional,what distinguishes actions (the things to which the term 'moral' applies) are those reasons,and it's that matter over which there's so little agreement. The question we actually have to answer is "is torturing this person in this circumstance, moral". The answer to that question will not yield much agreement and disagreement will hinge on those 'reasons'.

What are some arguments against, say, cognitivism, that you'd like to see me respond to? — Tarrasque

I think im going through some of them already, so I'm already getting the answers I'm looking for, thanks.

Funnily enough, I don't think that quality of reasoning is subjective. — Tarrasque

No, I suspected not. Perhaps that's for another day though.

Evaluating the outcome of a decision is reasoning about it. — Tarrasque

It is, but the evaluation includes the outcome in a way that evaluation of arguments doesn't.

To take your lottery example. Imagine you bought those thousand rickets and won a thousand times, you do the same next week and again the week after, the same thing happens. Is it still a bad decision, simply because it 'ought to be' on the basis of the evidence? Clearly the success of the outcome must cause us to review our assessment of the decision, we must have got something wrong somewhere.

In addition, what we believe are reasoned decisions are very often not. Even High Court Judges hand down longer sentences when they're hungry than they do when they're not. 'Reasoning' is often used just to bolster the authority of a decision made with very little prior thought. -

Tarrasque

31

Tarrasque

31

I don't see any widespread agreement on those matters. Torturing someone for no reason, is just definitional,what distinguishes actions (the things to which the term 'moral' applies) are those reasons,and it's that matter over which there's so little agreement.

I said "torturing someone for no reason other than personal pleasure."

Consider, "murder is wrong." Since "murder" means "unjustified killing," it seems almost trivial, since you would say that what matters is whether or not people agree that a given killing is murder. While people might disagree about whether a given killing is in fact sufficiently justified, they agree that if it is unjustified, it is wrong. There seems to be a need for killing to be reasonably justified in a way that we don't need to justify, say, going for a walk.

It is, but the evaluation includes the outcome in a way that evaluation of arguments doesn't.

To take your lottery example. Imagine you bought those thousand rickets and won a thousand times, you do the same next week and again the week after, the same thing happens. Is it still a bad decision, simply because it 'ought to be' on the basis of the evidence? Clearly the success of the outcome must cause us to review our assessment of the decision, we must have got something wrong somewhere.

"The success of the outcome causing us to review our assessment of the decision" is reasoning. If it seems that I can consistently win lotteries, entering lotteries might appear more reasonable. Remember, I did not say that reasoning makes a decision better. I said that more well-reasoned decisions are likely or often better decisions. I might make a well-reasoned decision to go to the bank today, and then get struck by lightning the moment I step out the door. This would be a terrible outcome, but this doesn't mean my decision to go to the bank was not likely to have a good outcome. Its likelihood to have a good outcome was probably a large part of what made it seem to be a good decision.

But past probabilities do not affect future probabilities. In considering the lottery, none of my past wins indicate a heightened probability of a future win. This is just like how, in a series of a hundred coin flips, getting tails 99 times does not mean there is more than a 50% chance my next flip will be heads.

The exception would be if I have been winning the lottery due to a reliable cause, like a "guardian angel" arranging that I will usually get a winning ticket. If I have reason to believe I have such a guardian angel, I may always have reason to buy another ticket. Otherwise, no matter how many times I have won in the past, buying another ticket is always a bad decision.

In addition, what we believe are reasoned decisions are very often not. Even High Court Judges hand down longer sentences when they're hungry than they do when they're not.

I'm sure this is the case. I don't think human beings are flawless automatons of reason. People often take themselves to have a reason to do or believe something, and then later realize they were mistaken. Sometimes, they never realize they were mistaken at all.

No, I suspected not. Perhaps that's for another day though.

If you do want to get into this, define what you mean by "subjective" and explain how you think it applies to reasoning. -

Isaac

10.3kThere seems to be a need for killing to be reasonably justified in a way that we don't need to justify, say, going for a walk. — Tarrasque

Isaac

10.3kThere seems to be a need for killing to be reasonably justified in a way that we don't need to justify, say, going for a walk. — Tarrasque

I see what you mean. I wouldn't call that moral agreement because I'm seeing the justification to be the meat of any moral dilemma, not the need for it. I don't know if I've mentioned it here or in another thread (there's a few 'morality' threads on the go at once), but I think it's quite irrefutable that most people are either born with, or are predisposed to develop, a basic set of what we might call moral imperatives. We sense other's pain and try to minimise it, we sense other's intentions a try to help and we are drawn to to other people who appear to act the same. The problem I have with deriving any moral realism from these facts is that it ends up saying nothing at all about actual moral dilemmas as they appear to us. To me, a moral dilemma is only a dilemma because the answer is not delivered to us automatically by those same set of basic instincts.

"The success of the outcome causing us to review our assessment of the decision" is reasoning. — Tarrasque

Yes, but we were talking about prior reasoning - determining the 'best' decision prior to being apprised of the outcome.

I might make a well-reasoned decision to go to the bank today, and then get struck by lightning the moment I step out the door. This would be a terrible outcome, but this doesn't mean my decision to go to the bank was not likely to have a good outcome. Its likelihood to have a good outcome was probably a large part of what made it seem to be a good decision. — Tarrasque

Right. So how is reasoning delivering us probabilities? If, as you say "past probabilities do not affect future probabilities" then we're not simply using frequentist probabilities, we must be using Bayes. How do you imagine reasoning actually working here - step-by-step what does it do, do you think? Say I'm trying to decide whether to wear my coat The weather report says it's going to rain, but the sky looks clear and blue. I decide not to wear my coat and enjoy a sunny day without the extra burden. Was my decision right or wrong? How do I judge the quality of my reasoning prior to knowing the outcome?

I don't think human beings are flawless automatons of reason. People often take themselves to have a reason to do or believe something, and then later realize they were mistaken. Sometimes, they never realize they were mistaken at all. — Tarrasque

So, the point here is that we'd never know. A moral system based on reasoning would be completely indistinguishable from one based on gut feeling because we'd have absolutely no way of telling if the reasoning is post hoc rationalisation of what we we're going to do anyway, or genuine reasoning. what I find disturbing about all these "I've worked out how to decide what's moral or not" type of models (we seem to get a half dozen of them every week) is that they try to add a gloss of authority to moral resolutions which we have absolutely no way of distinguishing from gut feeling (or worse, political ideology). The mere fact that they can be parsed into some rational algorithm doesn't distinguish them because the real meat of moral dilemmas are sufficiently complex that any decision could be similarly parsed.

The judges don't agree they're influenced by hunger by the way, they all think they're the exception. -

Tarrasque

31

Tarrasque

31

I think it's quite irrefutable that most people are either born with, or are predisposed to develop, a basic set of what we might call moral imperatives. We sense other's pain and try to minimise it, we sense other's intentions a try to help and we are drawn to to other people who appear to act the same.

I totally agree. Humans have innate moral sensibilities. We often perceive something, and without more than a thought about it, we will judge it as right or wrong. Humans are not unique in this regard. I've seen studies implying that chimpanzees have a sense of fairness, and will freak out if they're rewarded worse than another chimp doing the same task as them.

Gravity is another thing that humans have innate sensibilities about. We've always known that if something goes up, it must come down. If a rock is falling, we ought to get out of the way. Our intuitions about gravity are reliable, but not always. We weren't doing exact calculations until we had theories. We can say the same about mathematics. We could count objects, find symmetry in the face of a partner, divide things into groups - without theories of mathematics.

The fact that a crude evaluative mechanism for some subject has arisen biologically within us does not mean that there is no truth to be found in that subject.

To me, a moral dilemma is only a dilemma because the answer is not delivered to us automatically by those same set of basic instincts.

Our moral questions are more complicated today. If people encountered a man amidst a field of fresh corpses, bashing in skulls with a rock, holding a baby upside down by the leg, they might ask what he was doing. If he replied that he was killing people purely because he felt like it, for no reason other than his own pleasure, who among the spectators would not judge him as wrong automatically? In such a case, I believe the consensus would be as good as unanimous. Do you think it'd be a less certain consensus than those about physical intuitions?

How do you imagine reasoning actually working here - step-by-step what does it do, do you think? Say I'm trying to decide whether to wear my coat The weather report says it's going to rain, but the sky looks clear and blue. I decide not to wear my coat and enjoy a sunny day without the extra burden. Was my decision right or wrong? How do I judge the quality of my reasoning prior to knowing the outcome?

Reasoning consists in weighing the considerations for and against a given action or belief. Everybody reasons about things at least some of the time. How do you imagine that "judging" the quality of reasoning works? Would you say it's just looking at how it worked out for you after the fact?

Imagine someone who regularly takes unfavorable risks, is inconsistent, and barely thinks about anything at all before he does it. When he achieves his aims, it's pure luck. But, as it turns out, he gets lucky a lot. Is a person like this a good decision-maker? Should he be in a leadership role, or working as a consultant?

I don't deny that the outcome is important. If I left my jacket and it's sunny, I'm happy with the outcome! If I left my jacket and it rains, I am not happy. When I'm standing there wet, I might think that I made a bad decision to leave my jacket at home. This could be a psychological trick: think the poker player who goes all-in on an incredible hand and unluckily loses. He might think he made a bad decision, but did he really? If he has the same hand again, all else being equal, he should go all-in again. He made the best decision he could with the information he had available. A good decision can result in a bad outcome, and a bad decision can result in a good outcome.

So, the point here is that we'd never know. A moral system based on reasoning would be completely indistinguishable from one based on gut feeling because we'd have absolutely no way of telling if the reasoning is post hoc rationalisation of what we we're going to do anyway, or genuine reasoning.

Couldn't you say the same about math, or logic? At the end of the day, we only believe that the Law of Non-Contradiction is true because we really, deep down, feel like it's true. Are we just post-hoc rationalizing our gut feeling? Perhaps, but this isn't obvious.

We could even say the same about our physical intuitions. Deep down, I feel like it's true that larger objects can't fit inside smaller ones. But how do I know? I haven't tried to fit every object in the universe inside every other. What if I met someone who claimed otherwise?

what I find disturbing about all these "I've worked out how to decide what's moral or not" type of models (we seem to get a half dozen of them every week) is that they try to add a gloss of authority to moral resolutions which we have absolutely no way of distinguishing from gut feeling (or worse, political ideology).

Have you read much moral philosophy?

Given your concerns about reasoning, I'd like to introduce you to the concept of "reflective equilibrium." This is the idea that the beliefs we are most justified in holding are the ones that have, upon the most reflection, remained consistent. Reasoning is done by comparing "seemings," or "things that seem to be the case." These seemings are defeasible: a less convincing seeming is often discarded in favor of a more convincing one.

The bedrock of this system are those seemings which, after the most reflection(which consists in examining seemings and comparing seemings), are the most stable. Take your example that larger objects cannot fit inside smaller ones. This seeming has been consistent with everything you have ever experienced in your life. Not only this, but it seems intuitively true based on what "larger" and "smaller" mean. I'm sure that the more you consider it, the more sure you are of it. What would it take to defeat this seeming?

The more we consider our seemings, the more we approach reflective equilibrium. We do this in our own minds, and we do it with other people dialogically. The most important thing to remember is that we could always be wrong. As you rightly point out, reasoning is fallible. It falls back on judgment. But, this alone should not discourage us from our pursuit of truth. -

Pfhorrest

4.6kSorry it's taken to long to get back to this, besides my birthday Saturday my Sunday got really unexpectedly busy.

Pfhorrest

4.6kSorry it's taken to long to get back to this, besides my birthday Saturday my Sunday got really unexpectedly busy.

This can be explained easily in terms of second-order desires. I might have a certain desire, but desire not to have that desire. In such a case, the "desire I wish I had" is not affecting my actions, but the "desire I do have" is. Being a slave to my vices might be my first-order and second-order desires conflicting. If X being good is a belief, I can sincerely hold that X is good and yet not intend to X. While I want-to-want-to-X, I unfortunately don't want-to-X. — Tarrasque

Intentions, as I mean them, are "second-order desires", in the same way that beliefs are "second-order perceptions", though neither in quite so straightforward a way, hence the quotes here. "Thoughts" in general (beliefs and intentions) are, on my account, what happens when we turn our awareness and control inward, look at our "feelings" (desires and perceptions) and then judge whether they are correct or not. To think something is good and to intend it are thus synonymous: the thing that you think is good, that you intend, is the thing that you judge it would be correct for you to desire.

You still might nevertheless not desire it, just like disbelieving an illusion doesn't make you not perceive it, but just as believing is thinking something is true, intending is thinking something is good, which is different from just desiring it (feeling like it's good), just as belief is different from perception (feeling like it's true).

This seems to imply that, in deliberating different options, only the maximal one is "good." This precludes the idea of deliberating between multiple good options. It doesn't follow that just because going to the gym is not the most good, it is not good at all.

"Going to the gym is good, but I don't intend to go to the gym." could reflect that I am not going to the gym because of a conflicting greater good, I agree. But, I can still cogently evaluate going to the gym as good, while not intending to do it. — Tarrasque

The distinction here is between a general evaluation of the goodness of going to the gym, and the goodness of you in particular going to the gym right now in particular. You can intend to regularly go to the gym, think it's good for you to do so, but because your kid just broke a leg and needs to be taken to the hospital, intend not to go to the gym right now, because you think it would be bad if you went to the gym right now instead of taking your kid to the hospital.

Just like how saying "it's true that horses have four legs" means it's generally true that usually horses have four legs, but that doesn't mean some particular horse cannot only have three legs. Sometimes it's false that some horse has four legs.

So, if I understand you correctly, experiencing a first-person appetite is an irreducible ought. I'm still not confident that this is the case. The fact of my appetitive experience is a physical fact, even from the first-person perspective. If I were in pain, I could, say, go through an MRI and verify that I am in fact in pain. Of course, I don't need to do this to have the experience of being in pain. Similarly, I don't have to go through an MRI to verify that I am having a perceptive experience of looking at a painting. If where I have pain, I have an ought, there seems to be a relationship between "me factually being in pain" and "what ought to be the case.". — Tarrasque

An MRI is a third person description of you, not your own first-person experience. Completely regardless of what a third-person description of the mechanics underlying someone's experience of pain, their first-person experience of that pain is what moral judgements are to be measured against. (And NB that "X will hurt" isn't the meaning of "X is bad" on my account; the meaning is something more like "avoid X". Whether it hurts anyone is just part of the criteria to use for judging whether or not to agree to avoid X, to agree that X is bad, just like empirical sensations are the criteria to use for judging whether or not to agree that something is descriptively true).

In the same vein as above, do you think that "I am hungry, yet I ought not to be fed." is some kind of paradox? If "I am hungry" entails "I ought to be fed," it must be

[...]

Bloodlust could easily be defined in terms of an appetite, though. What makes hunger an appetite? It is an experience of a certain sort that can only be satisfied by an actualization through my sensations, in the case of hunger, me being fed. — Tarrasque

This isn't really acknowledging the distinction between experiences and feelings, which is crucial to my account. Experiences aren't propositional; you don't experience that something is true or that something is good. "I am hungry" doesn't directly entail "I ought to be fed"; rather, feeding me is merely one thing that can result in satisfying my hunger. Anything else that could satisfy my hunger would equally suffice; say, some caffeine, which suppresses hunger. In contrast, bloodlust is specifically a desire for someone to hurt, it has propositional content, a particular state of affairs in mind. That state of affairs doesn't have to be realized, on my account, but the experiences in response to which someone desires that state of affairs does, somehow, without disregarding others', to bring about a universally good state of affairs.

(Of course, we'll always fall short of universally good, just like we'll always fall short of universally true belief, but the procedures for how to deal with those shortcomings are topics about epistemology and a part of what's usually considered normative ethics, which I'm planning later threads about; they're not necessary just to talk about what things mean).

It's the blind men and the elephant again. The tail-guy's perception of a rope doesn't have to be satisfied for a universally true description of what they're feeling, but the sensations he has that inspire him to perceive a rope do need to be satisfied: to be true, the answer "it's an elephant" needs to account for why tail-guy perceives something rope-like, and thankfully it does.

Likewise the sadist's bloodlust, his desire to kill, doesn't have to be satisfied for a universally good prescription, but his appetites, the experiences that inspire him to desire to kill, do need to be satisfied, somehow, or else there is still some bad going unresolved, some suffering that he is undergoing without respite. That satisfaction could involve some other outlet, some kind of medication, some other therapy, something, but it doesn't have to (and of course shouldn't) involve him actually killing people.

But there is still an elephant. They may not be making methodological mistakes, but their perceptions of various objects where there is in fact an elephant represents a deviation from what is actual. — Tarrasque

Is there actually an elephant, when there is no possibility in principle of anybody ever telling that there is one instead of e.g. a rope? Bearing in mind that if there is no way in principle of them communicating with each other or anything they have mutual access to, then on what grounds could you say they even exist together in the same world? When we imagine this, we're imagining that you and I have some kind of privileged access where we're aware of all three of them and of the elephant, but they're all absolutely blocked off from awareness of each other or of any part of the elephant besides their tiny little bit. But if we can interact with them (to observe them), and with the whole of the elephant (to observe it), then in principle there is a communication channel, through us, by which they could observe each other and the whole of the elephant. You can't really seal parts of the universe off from each other completely like that, without effectively removing them from each other's universes, separating them into separate bubble worlds, in which case why couldn't different things be true in different worlds?

I definitely don't think that we necessarily interpret it as an utterance. "Expression" and "impression" seem to be, as you have so far used them, properties related to what a speaker is intending with their words. What you're now saying implies that if I take someone to be impressing a belief on me, they are in fact doing so.

In the case of the dead bugs, applying "expression" or "impression" in the intentionary sense is a clear error. What am I applying them to? The dead bugs? The piece of paper? If a piece of paper that was written on by nobody can cogently be claimed to impress/express beliefs, the terms become a lot less meaningful. I can similarly say that a mountain impresses on me the belief that it is large when I look at it. — Tarrasque

All linguistic meaning is inferred by the audience about the speaker. If you read the bugs as words and not just as bugs, you're already reading them as though they are an utterance by some speaker. What kind of utterance you interpret them as determines how and whether you will evaluate the truth (in the broad sense, i.e. correctness) of them. Actual speakers use words that have agreed-upon meaning in the linguistic community to try to convey various meanings to their audience, but it's always up to the audience what meaning they will take away from it. If there is no actual speaker (or writer, etc) at all, then there is no actual meaning being conveyed in the first place. If an audience nevertheless reads in meaning to something that's actually meaningless (like a random pattern of dead bugs), it's up to the audience to read in what their imaginary speaker meant to convey by their message.

E.g. if the dead bugs say "I don't like your hat", but there isn't actually anybody who doesn't like anyone's hat who wrote that, the dead bugs just look like that sentence, what meaning should a reader take away from it? Who should they feel insulted by? Nobody, because nobody actually wrote that.

With these clarifications, you will have to retreat to the weaker claim that they only resolve Moore's paradox from the perspective of someone who assigns impression/expression to the sentence in the same way that you have. If their evaluation of impression/expression differs from yours, they are still correct in taking Moore's paradox to self-contradict. You might be fine with this conclusion. — Tarrasque

Sure, if they take Moore's sentence to mean "I believe X but I don't believe X" or "X is true but X is false" or something like that, then they can take it to be contradictory. My account of impression/expression is an account of why it seems like it shouldn't seem contradictory, but nevertheless it does seem contradictory, i.e. why this is a "paradox" and not just an obvious either contradiction or non-contradiction. Someone who took Moore's sentence to mean one of the things above wouldn't see anything paradoxical about it, but people generally do, so some explanation of the differences and relations in meaning between "I believe X" and "X is true" is needed to account for why they do.

This restructuring alone does not resolve the Frege-Geach problem. A statement of the formal form be(P being Q) is a prescription. Its utterance prescribes a state of affairs. This is clear in the case of the atomic sentence P1: be(X being F), or "it ought not to be the case that there is stealing," if you'd rather. Prescription is the semantic content of that proposition. In the context of the antecedent in P2(IF be(X being F), then...), the semantic content of "be(X being F)" does not prescribe. We see, then, that be(X being F) in P1 and be(X being F) in P2 have different semantic content. In classical logic, we would now have to use different variables to represent them, and our modus ponens would no longer be valid. — Tarrasque

Remember that "be(x being F)" is a shorter form of something like "it-ought-to-be-the-case-that-there-is(x being F)". Likewise "is(x being F)" is a shorter form of something like "it-is-the-case-that-there-is(x being F)". These are meant to be equivalent to "x ought to be F" and "x is F"; we're just pulling the "is"-ness and "ought"-ness out into functions that we apply to the same object, the same state of affairs, "x being F".

So if "if x ought to be F, then..." is no problem, then "if be(x being F), then ..." should be no problem either, because the latter is just an encoding of the former in a formal language meant to elucidate the relations between "is" and "ought" statements about the same state of affairs.

I only use the imperative form of the copula, "be", to name that function, because I take "oughts" to be a kind of generalization of imperatives: "you ought to F" and "you, F!" are equivalent on my account, but you can say things of the form "x ought to be G" that can't be put into normal imperative form. "Oughts" are more like exhortations than imperatives: "Saints be praised!" isn't an order to the saints to go get praised, but it is basically the same as a general imperative to everyone (but nobody in particular) to "praise the saints!" and also basically the same as "the saints ought to be praised", which likewise implies that everybody (but nobody in particular) ought to "praise the saints!"

The importance of using "truth," for me, is the consistency with the vernacular in logic. Formal logical relationships, most crucially entailments, are based in the truth or falsity of their propositions. Claiming that something is "not truth-apt" should imply that it is not evaluable in formal logic, not usable to form valid arguments, etc. Since you use "correctness" in the same way "truth" is used in logic, I think it is important to call it truth. — Tarrasque

Perhaps we could more neutrally distinguish them as "cognitive truth" and "descriptive truth", since the most important feature of my moral semantics is rejecting descriptivism without rejecting cognitivism. On my account moral claims are "truth-apt" in the sense that matters for cognitivism, but not "not truth-apt" in the sense that matters for descriptivism. They're not telling you something about the way the world is, but they are nevertheless fit to be assigned yes/no, correct/incorrect, 1/0, "truth" values.

The particular words used to distinguish these two concepts don't really matter to me at all, just that they are distinguished, and not conflated together: that not only descriptions are taken to be apt to bear the kind of boolean values needed to do logic to them.

I have your principle of descriptive truth down, I think: "X is a descriptive truth if and only if X is, in principle, empirically verifiable as true."

What I'm after is a similar principle for your establishment of moral correctness. "X is a correct prescription if and only if..." what? You have explained your idea of prescriptive correctness, but I've found these explanations a little vague. I'm looking for a definition of what "prescriptive correctness" really is, in the form of a principle, like the above for descriptive truth. I'd have trouble trying to just throw "appetitive experiences of seeming good or bad in the first-person" into a principle like that without horribly misinterpreting and butchering what you're saying. — Tarrasque

I would state the parallel principles instead as:

"X is descriptively true if and only if X satisfies all sensations / observations"

and

"X is prescriptively good if and only if X satisfies all appetites".

Claims that something is descriptively true or that something prescriptively good can both be "cognitively true" / correct in the same way, they can both carry boolean values that can be processed through logical functions.

But this is getting away from mere philosophy of language; I almost went into a huge multi-paragraph thing about epistemology and the ethical equivalent thereof here.

The meanings, on my account, of ordinary non-moral claims, and moral claims, respectively, are to impress upon the audience either a "belief", an opinion that something is (descriptively) true, that it is, that reality is some way; or an "intention", an opinion that something is (prescriptively) good, that it ought to be, that morality is some way.

It's technically a different question as to what kinds of states of affairs can be real or can be moral, and then a further question still as to how we sort out which of such states of affairs actually is real or moral to the best of our limited abilities. Those are topics I intend to have later threads about: ontology and epistemology, and two halves of what's usually reckoned as normative ethics which I term "teleology" and "deontology".

The relationship between "murder is wrong" and "you ought not to murder" is that "you ought not to do what is wrong." The non-naturalist has no problem assuming this premise, and neither do you. In fact, you seem to espouse(in agreement with many realist positions) that what is wrong is implicitly that which you ought not to do. If this counts as crossing the is-ought gap, then you cross it yourself when you hold "murder is wrong" as interchangeable with "it ought not to be the case that there is murder." Also — Tarrasque

The difference is that I'm not claiming "X is wrong" describes some kind of abstract moral property of wrongness of object X, and that on account of that property, we ought not to do X. I claim that "X is wrong" just means "X ought not happen", which in turn is a more general, universal form of sentences like "(everybody) don't do X" or "let X not happen!"

Somewhat, but also somewhat not. Take the example of information on the edge of the observable universe. It is, even in principle, impossible for us to verify that information. This is because part of what it means to be us is that we are here, and if we cannot verify some information from here or somewhere we can get to from here, it is not verifiable at all to us. You could stipulate that if someone was on the edge of our observable universe, that information would be verifiable to someone. So, in one sense it is verifiable "in principle," but it is not verifiable "to us" in principle. — Tarrasque

This seems related to the black hole information paradox. The edge of the universe is the cosmic event horizon. It was a problem that information could seem to be lost when falling across a black hole event horizon. If it had been actually lost, then so far as I know, just like particles actually having no definite position, the universe would actually be indeterminate about that state of affairs. If the universe has any information about some state of affairs, if that state of affairs actually exists, then it will have some impact on something about the universe; and even if we're not technologically capable of reconstructing the information from that impact, that information has nevertheless reached us in the form of that impact.

That black hole information paradox got solved in a way that the information wasn't actually lost, because the infalling particles have effects on the stuff happening right at the event horizon, which does eventually bring the information back to us in the form of Hawking radiation. It seems like lightspeed particles moving away from us at the edge of the universe could have some impact on the other stuff there at the edge of the universe that is still capable of communicating with us, and so information about that escaping stuff could still make its way back to us in principle.

If you are going to assert that mathematical truths are merely truths of relations between ideas, belonging in the middle of your fork, you need to support that. This would require an account of analyticity. Distinguishing between "things that are true by definition" and "things that are true in virtue of a contingent fact" is much harder than you might initially think. — Tarrasque

I have a whole thing about the contingent facts about definitions (and, hence, analytic a posteriori facts) that I'm going to do a later thread about.

"What conditions would a person have to satisfy for them to have knowledge of X?"

The latter is my question to you. If what can be true is constrained by what we can know, then before we ask what is true, we ought to ask what we can know. Before we know what we can know, we must know what it is to know at all. So, what conditions does a person have to satisfy to have knowledge of X? — Tarrasque

I plan to do a later thread on this topic, so I'll defer answering until then. -

Tarrasque

31

Tarrasque

31

Happy birthday!

Intentions, as I mean them, are "second-order desires", in the same way that beliefs are "second-order perceptions", though neither in quite so straightforward a way, hence the quotes here. "Thoughts" in general (beliefs and intentions) are, on my account, what happens when we turn our awareness and control inward, look at our "feelings" (desires and perceptions) and then judge whether they are correct or not. To think something is good and to intend it are thus synonymous: the thing that you think is good, that you intend, is the thing that you judge it would be correct for you to desire.

I think this is a plausible enough account. I don't find it strikingly more plausible than moral opinions just being beliefs, but it works well on its own terms.

Just as beliefs could be described as perceptions about our perceptions, intentions could be described as desires about our desires. Is something like this what you are implying?

Bearing in mind that if there is no way in principle of them communicating with each other or anything they have mutual access to, then on what grounds could you say they even exist together in the same world?

It's not clear that an ability to communicate is a necessary feature of conscious beings. I don't find it problematic to imagine a single world that contains three beings who cannot communicate with each other. A conscious being could have no ability to manipulate its own body, for instance.

When we imagine this, we're imagining that you and I have some kind of privileged access where we're aware of all three of them and of the elephant, but they're all absolutely blocked off from awareness of each other or of any part of the elephant besides their tiny little bit. But if we can interact with them (to observe them), and with the whole of the elephant (to observe it), then in principle there is a communication channel, through us, by which they could observe each other and the whole of the elephant.

I certainly wasn't imagining this. I was imagining three men and an elephant, not myself watching three men and an elephant. When we stipulate a hypothetical, just "what if X," it's not required that we assume we are there watching X. I can cogently say "let's assume a hypothetical world where neither of us exist." We couldn't possibly be in such a scenario to observe ourselves. We can still talk about what might be the case if it were true.

I don't think you have sufficient grounds to claim that three beings who cannot communicate must therefore be in different worlds.

E.g. if the dead bugs say "I don't like your hat", but there isn't actually anybody who doesn't like anyone's hat who wrote that, the dead bugs just look like that sentence, what meaning should a reader take away from it? Who should they feel insulted by? Nobody, because nobody actually wrote that.

Yes, I agree with this. Of course, if they interpret the sentence as expressive, impressive, descriptive, imperative, whatever, this will change if and how they will truth-evaluate the sentence.

Sure, if they take Moore's sentence to mean "I believe X but I don't believe X" or "X is true but X is false" or something like that, then they can take it to be contradictory. My account of impression/expression is an account of why it seems like it shouldn't seem contradictory, but nevertheless it does seem contradictory, i.e. why this is a "paradox" and not just an obvious either contradiction or non-contradiction. Someone who took Moore's sentence to mean one of the things above wouldn't see anything paradoxical about it, but people generally do, so some explanation of the differences and relations in meaning between "I believe X" and "X is true" is needed to account for why they do.

I see. We're in agreement here.

Remember that "be(x being F)" is a shorter form of something like "it-ought-to-be-the-case-that-there-is(x being F)". Likewise "is(x being F)" is a shorter form of something like "it-is-the-case-that-there-is(x being F)". These are meant to be equivalent to "x ought to be F" and "x is F"; we're just pulling the "is"-ness and "ought"-ness out into functions that we apply to the same object, the same state of affairs, "x being F".

So if "if x ought to be F, then..." is no problem, then "if be(x being F), then ..." should be no problem either, because the latter is just an encoding of the former in a formal language meant to elucidate the relations between "is" and "ought" statements about the same state of affairs.

By your account of what "if x ought to be F, then..." means, it is just as problematic as "if be(x being F)." Like you say, they are equivalent in meaning.

The problem is arising due to you interpreting all moral statements as prescriptions.

I take "oughts" to be a kind of generalization of imperatives: "you ought to F" and "you, F!" are equivalent on my account, but you can say things of the form "x ought to be G" that can't be put into normal imperative form. "Oughts" are more like exhortations than imperatives: "Saints be praised!" isn't an order to the saints to go get praised, but it is basically the same as a general imperative to everyone (but nobody in particular) to "praise the saints!" and also basically the same as "the saints ought to be praised", which likewise implies that everybody (but nobody in particular) ought to "praise the saints!"

This is still running into the Frege-Geach problem.

P1. The saints ought to be praised.

P2. If the saints ought to be praised, then the demons ought not to be praised.

C. The demons ought not to be praised.

An exhortation is "an address or communication emphatically urging someone to do something."

An imperative is "an authoritative command."

The important thing about both of these is that the semantic content of them is, necessarily, an urging. The fact that you class "the saints ought to be praised" as an exhortation means that, by speaking it in P1, I am necessarily urging that the saints be praised. However in P2, I say the same words as in P1, but I don't urge that the saints be praised or not praised. So, it seems that when I say "the saints ought to be praised," the content of my sentence cannot necessarily be any kind of imperative if we want moral modus ponens to work.

This is a problem that typical cognitivists, who would classify "the saints ought to be praised" as a claim purporting to report a fact, do not encounter.

Perhaps we could more neutrally distinguish them as "cognitive truth" and "descriptive truth", since the most important feature of my moral semantics is rejecting descriptivism without rejecting cognitivism. On my account moral claims are "truth-apt" in the sense that matters for cognitivism, but not "not truth-apt" in the sense that matters for descriptivism. They're not telling you something about the way the world is, but they are nevertheless fit to be assigned yes/no, correct/incorrect, 1/0, "truth" values.

Sure, that's better. I like the new terminology more.

I would state the parallel principles instead as:

"X is descriptively true if and only if X satisfies all sensations / observations"

and

"X is prescriptively good if and only if X satisfies all appetites".

Claims that something is descriptively true or that something prescriptively good can both be "cognitively true" / correct in the same way, they can both carry boolean values that can be processed through logical functions.

I'll remember this. My main discomfort with it is the conflation of ontology with epistemology, "what we can know" and "what is" becoming the same concepts. But, we're already discussing that as we discuss verificationism.

The meanings, on my account, of ordinary non-moral claims, and moral claims, respectively, are to impress upon the audience either a "belief", an opinion that something is (descriptively) true, that it is, that reality is some way; or an "intention", an opinion that something is (prescriptively) good, that it ought to be, that morality is some way.

If the meaning of regular descriptive claims has to to impress a belief, this seems like it will subject non-moral modus ponens to the Frege-Geach problem as well.

It's technically a different question as to what kinds of states of affairs can be real or can be moral, and then a further question still as to how we sort out which of such states of affairs actually is real or moral to the best of our limited abilities. Those are topics I intend to have later threads about: ontology and epistemology, and two halves of what's usually reckoned as normative ethics which I term "teleology" and "deontology".

I'll see you there, then.

The difference is that I'm not claiming "X is wrong" describes some kind of abstract moral property of wrongness of object X, and that on account of that property, we ought not to do X. I claim that "X is wrong" just means "X ought not happen", which in turn is a more general, universal form of sentences like "(everybody) don't do X" or "let X not happen!"

The is-ought distinction isn't an inherent problem with deriving moral claims from properties. For example, the following deduction respects the is-ought gap:

P1. X is painful.

P2. If X is painful, then we ought to avoid X.

C. We ought to avoid X.

A view espousing the above might be vulnerable to the Open Question Argument, but because it includes a normative premise, it's not an issue with the is-ought gap. For a non-naturalist or non-reductionist, the property of interest isn't pain, it just is "wrongness." So, a non-naturalist deduction might look like:

P1. X is wrong.

P2. If X is wrong, then we ought not to X.

C. We ought not to X.

So yes, there is a difference between your account and a realist account. But, this difference has no effect on the relevance of the is-ought distinction.

That black hole information paradox got solved in a way that the information wasn't actually lost, because the infalling particles have effects on the stuff happening right at the event horizon, which does eventually bring the information back to us in the form of Hawking radiation. It seems like lightspeed particles moving away from us at the edge of the universe could have some impact on the other stuff there at the edge of the universe that is still capable of communicating with us, and so information about that escaping stuff could still make its way back to us in principle.

Yeah, I suppose that could be. In that sense, every bit of matter present at the big bang could be said to have some residual effect on us. It's still possible that such an effect could be so miniscule or hard to measure that attempts to do so would require more energy than there is in the universe, or something like that. Such effects would be unverifiable in principle, but I expect that in such a case, you would say that they were literally indeterminate.

I have a whole thing about the contingent facts about definitions (and, hence, analytic a posteriori facts) that I'm going to do a later thread about.

I plan to do a later thread on this topic, so I'll defer answering until then.

Is all this information already written in your book? -

Isaac

10.3kThe fact that a crude evaluative mechanism for some subject has arisen biologically within us does not mean that there is no truth to be found in that subject. — Tarrasque

Isaac

10.3kThe fact that a crude evaluative mechanism for some subject has arisen biologically within us does not mean that there is no truth to be found in that subject. — Tarrasque

Depends what you mean by 'truth'. A whole other argument.

If he replied that he was killing people purely because he felt like it, for no reason other than his own pleasure, who among the spectators would not judge him as wrong automatically? In such a case, I believe the consensus would be as good as unanimous. Do you think it'd be a less certain consensus than those about physical intuitions? — Tarrasque

I think most people would (quite rightly) judge him 'ill', not 'wrong'. That's the point I was making about intuitive feelings of morally apt behaviour. They're just not relevant to actual moral dilemmas about which there's disagreement. The kind these 'moral systems' are aimed at. People supporting moral realism always seem to cite the agreement that would be had over some over-the-top act of evil, but ask yourself why have you had to choose such an example, and when was the last time you faced such a moral dilemma ("should I bash the people's skulls in or not?")? The answer to both will come down to the fact that real moral dilemmas are not solvable by relation to the instincts that we all share about empathy, care, and cooperation.

How do you imagine that "judging" the quality of reasoning works? Would you say it's just looking at how it worked out for you after the fact? — Tarrasque

Yes, in the long term. I think (after Ramsey) that reasoning is just a mental habit that turns out to be useful.

Imagine someone who regularly takes unfavorable risks, is inconsistent, and barely thinks about anything at all before he does it. When he achieves his aims, it's pure luck. But, as it turns out, he gets lucky a lot. Is a person like this a good decision-maker? Should he be in a leadership role, or working as a consultant? — Tarrasque

Possibly, yes. If it works I cannot see any reason why not. If he gets lucky a lot how are we calculating that it is just luck. If a coin lands on heads most of the time we presume a biased coin, not a lucky one.

Couldn't you say the same about math, or logic? At the end of the day, we only believe that the Law of Non-Contradiction is true because we really, deep down, feel like it's true. Are we just post-hoc rationalizing our gut feeling? Perhaps, but this isn't obvious.

We could even say the same about our physical intuitions. Deep down, I feel like it's true that larger objects can't fit inside smaller ones. But how do I know? I haven't tried to fit every object in the universe inside every other. What if I met someone who claimed otherwise? — Tarrasque

Yes, I suppose you could claim that, but it gets very difficult when it comes to the more advanced areas of maths, logic, and science. You could well argue that assuming the stone follows some physical law when it drops to the ground is just a post hoc rationalisation for my gut feeling that it would, but I don't see how you could argue that the energy level predicted of the Higgs Boson being found where the theory expected it to be was just a post hoc rationalisation of our gut feeling that it would be there.

I'd like to introduce you to the concept of "reflective equilibrium." This is the idea that the beliefs we are most justified in holding are the ones that have, upon the most reflection, remained consistent. Reasoning is done by comparing "seemings," or "things that seem to be the case." These seemings are defeasible: a less convincing seeming is often discarded in favor of a more convincing one.

The bedrock of this system are those seemings which, after the most reflection(which consists in examining seemings and comparing seemings), are the most stable. Take your example that larger objects cannot fit inside smaller ones. This seeming has been consistent with everything you have ever experienced in your life. Not only this, but it seems intuitively true based on what "larger" and "smaller" mean. I'm sure that the more you consider it, the more sure you are of it. What would it take to defeat this seeming?

The more we consider our seemings, the more we approach reflective equilibrium. We do this in our own minds, and we do it with other people dialogically. The most important thing to remember is that we could always be wrong. As you rightly point out, reasoning is fallible. It falls back on judgment. — Tarrasque

I don't have any disagreement with all this. It's not far off the way I imagine our judgements to be made. None of this defeats relativism (there's nothing about something 'seeming' to one person to be the case, even on reflection, that makes it more likely to actually be the case). Nor does anything here prevent judgements from being post hoc rationalisations (again things will 'seem to be the case' that suit a rational explanation for the actions we've already committed to) -

Tarrasque

31

Tarrasque

31

I think most people would (quite rightly) judge him 'ill', not 'wrong'. That's the point I was making about intuitive feelings of morally apt behaviour. They're just not relevant to actual moral dilemmas about which there's disagreement. The kind these 'moral systems' are aimed at. People supporting moral realism always seem to cite the agreement that would be had over some over-the-top act of evil, but ask yourself why have you had to choose such an example, and when was the last time you faced such a moral dilemma ("should I bash the people's skulls in or not?")? The answer to both will come down to the fact that real moral dilemmas are not solvable by relation to the instincts that we all share about empathy, care, and cooperation.

Moral agreement isn't so much an argument for moral realism as it is a counterargument to the argument from moral disagreement. You might claim that people disagreeing about morality gives us reason to think it's relative. A moral realist can point to the disagreement about matters of physical fact(climate change, age of the earth), and the agreement about basic moral fact(child torture, genocide).

Moral realists do not cite these things as arguments in favor of moral realism, but as a reminder to anyone who thinks that mere disagreement entails relativism.

Possibly, yes. If it works I cannot see any reason why not. If he gets lucky a lot how are we calculating that it is just luck. If a coin lands on heads most of the time we presume a biased coin, not a lucky one.

I'm stipulating that it is just luck. This is someone who makes erratic, unconsidered decisions. Due to purely situational luck, he has an excellent track record. Is he a good decision maker?

Yes, I suppose you could claim that, but it gets very difficult when it comes to the more advanced areas of maths, logic, and science. You could well argue that assuming the stone follows some physical law when it drops to the ground is just a post hoc rationalisation for my gut feeling that it would, but I don't see how you could argue that the energy level predicted of the Higgs Boson being found where the theory expected it to be was just a post hoc rationalisation of our gut feeling that it would be there.

This is a good point. We don't tend to have intuitions about these high-level concepts beyond "it makes sense" or "it doesn't make sense."

I don't have any disagreement with all this. It's not far off the way I imagine our judgements to be made. None of this defeats relativism (there's nothing about something 'seeming' to one person to be the case, even on reflection, that makes it more likely to actually be the case).

No, it does not defeat relativism. But neither does

"(there's nothing about something 'seeming' to one person to be the case, even on reflection, that makes it more likely to actually be the case)"

imply relativism. Even if my seemings are completely divorced from what is the case, that doesn't entail relativism. It entails that I'm wrong.

Looking at the totality of our decision-making through the lens of reflective equilibrium is helpful to discard the notion that there is anything inherently special about "science experiments" for finding truth. Whether we are judging scientific data or a mathematical proof, its plausibility to us is ultimately filtered through our intuitions. Some people find what they take to be intuitions about moral facts(slavery is wrong!) to be among their most stable seemings. Many people share these same reflective intuitions, about equality, fairness, and justice. Moral theories are seen as more plausible when they explain our foundational moral seemings effectively. While relativism is not "proven" wrong, many realists find that they have just as much justification to believe that slavery is wrong as they do anything else they believe. -

Isaac

10.3kMoral realists do not cite these things as arguments in favor of moral realism, but as a reminder to anyone who thinks that mere disagreement entails relativism. — Tarrasque

Isaac

10.3kMoral realists do not cite these things as arguments in favor of moral realism, but as a reminder to anyone who thinks that mere disagreement entails relativism. — Tarrasque

it does not defeat relativism. But neither does

"(there's nothing about something 'seeming' to one person to be the case, even on reflection, that makes it more likely to actually be the case)"

imply relativism. — Tarrasque

While relativism is not "proven" wrong, many realists find that they have just as much justification to believe that slavery is wrong as they do anything else they believe. — Tarrasque

Right. Which is pretty much where we get to.

Moral realists (or 'objectivists') have nothing more to support their claim than "it is not ruled out as an option".

I think parsimony (a principle I find mostly useful), would suggest relativism, as realism needs some objective truth-maker and we don't seem to be able to reach any kind of idea of what that might be. All that happens is the can gets kicked further down the subjective road.

A moral claim is taken to be correct if it somehow 'accounts for' everyone's intuitions - how do we judge if it's 'accounted' for them? Turns out that's just a subjective 'feeling' that it has. -

Pfhorrest

4.6kI think this is a plausible enough account. I don't find it strikingly more plausible than moral opinions just being beliefs, but it works well on its own terms. — Tarrasque

Pfhorrest

4.6kI think this is a plausible enough account. I don't find it strikingly more plausible than moral opinions just being beliefs, but it works well on its own terms. — Tarrasque

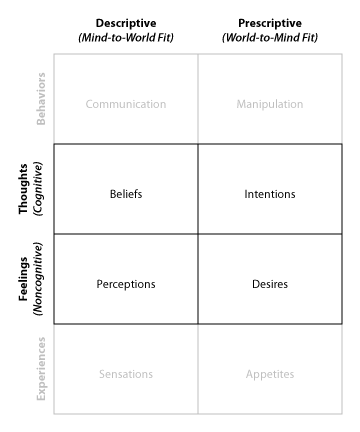

You could if you like think about it in different terms, without really changing anything about it. You could call what I call intentions "moral beliefs", and call desires something like "imperative perceptions", and then talk about "non-moral beliefs" and "non-imperative perceptions", with "belief" and "perception" as the more general terms in place of where I use "thought" and "feeling". Or call perceptions and desires “feelings” as I do, but call all “thoughts” “beliefs” and then separate them into “moral beliefs” and “non-moral beliefs”. I'm really not attached to the language, just the structure of the things named by whatever language. All that matters to me philosophically is that we distinguish the things in these boxes from each other, whatever we decide call them:

Choices of what to call them is a much more superficial matter.

Just as beliefs could be described as perceptions about our perceptions, intentions could be described as desires about our desires. Is something like this what you are implying? — Tarrasque

Something like it, but not quite exactly, because the second-order opinions ("thoughts") each involve both perceiving and desiring things about first-order opinions, it's just a difference as to which type of first-order opinion the reflexive perception-and-desire is about.

It's not clear that an ability to communicate is a necessary feature of conscious beings. I don't find it problematic to imagine a single world that contains three beings who cannot communicate with each other. A conscious being could have no ability to manipulate its own body, for instance. — Tarrasque

This is a matter of principle vs practice again. Anything that can have any causal effect on something else is in principle capable of communicating with it, even if in practice they have no conventional obvious communication ability. (There are some amazing hacks that can get information off of computers not connected to any network, or monitor speech in a room with a computer with no microphone, etc, by using overlooked tiny effects between hardware and software, for example). If two things are causally isolated such that in principle no information about one of them can reach anything that can reach the other one, then from each of their perspectives the other seems not to exist at all, so they’re basically in separate universes.

I certainly wasn't imagining this. I was imagining three men and an elephant, not myself watching three men and an elephant. When we stipulate a hypothetical, just "what if X," it's not required that we assume we are there watching X. I can cogently say "let's assume a hypothetical world where neither of us exist." We couldn't possibly be in such a scenario to observe ourselves. We can still talk about what might be the case if it were true. — Tarrasque

We necessarily imagine from some perspective or another though. If we imagine a world where we don’t exist, we imagine a world that doesn’t contain us as we really are, from some disembodied viewpoint. When we’re imagining the three men and the elephant, we’re imagining it from some viewpoint where we can observe all four of them. But if there isn’t actually any such viewpoint possible, because they’re all so completely isolated from each other, then all we should be imagining is each of their separate viewpoints, from which none of the others can ever seem to exist, nor the whole elephant, so what would it mean to claim that those things do exist, in some way that will never make any noticeable difference to anyone?

This is still running into the Frege-Geach problem.

P1. The saints ought to be praised.

P2. If the saints ought to be praised, then the demons ought not to be praised.

C. The demons ought not to be praised.

An exhortation is "an address or communication emphatically urging someone to do something."

An imperative is "an authoritative command."

The important thing about both of these is that the semantic content of them is, necessarily, an urging. The fact that you class "the saints ought to be praised" as an exhortation means that, by speaking it in P1, I am necessarily urging that the saints be praised. However in P2, I say the same words as in P1, but I don't urge that the saints be praised or not praised. So, it seems that when I say "the saints ought to be praised," the content of my sentence cannot necessarily be any kind of imperative if we want moral modus ponens to work.

This is a problem that typical cognitivists, who would classify "the saints ought to be praised" as a claim purporting to report a fact, do not encounter. — Tarrasque

Conditional imperatives make perfect sense. It helps to remember that material implication is equivalent to a kind of disjunction: “if P then Q” is exactly equivalent to “Q or not P”. I can easily command someone to do Q or not do P, which is the logical equivalent of ordering them to do Q if they do P, or “if you do P, do Q”, without any kind of embedding trouble. It might look like there should be in the “if-then” form, but there’s clearly none in the “or” form which is identical to it.

It might also help to resolve the appearance of the problem if we factor the “be()” out to the whole conditional at once:

be(the saints being praised only if the demons being not praised)

or

be(the demons being not praised or the saints being not praised)

If the meaning of regular descriptive claims has to to impress a belief, this seems like it will subject non-moral modus ponens to the Frege-Geach problem as well. — Tarrasque

If that were a problem, then every account of what people are doing with words would be subject to the same problem. If you take an ordinary indicative sentence to be reporting a fact, as you say, that’s still doing something, but in the antecedent of a conditional is it still doing that same fact-reporting? Whatever solution allows ordinary conditionals to work there, it should also work for whatever else other kinds of speech are doing, so long as there is a “truth-value” that can be assigned to that kind of speech, i.e. each such utterance is either a correct or incorrect utterance of that kind.

Is all this information already written in your book? — Tarrasque

Yes. I used to be doing a series of threads asking people to review chapters of the book itself, but a mod asked me to stop that as too self-promotional. So instead, at their suggestion, I'm just starting discussions about the ideas (that I've already written about) that I expect will be new to people (and skipping over the things that I expect will be old hat and just rehash arguments everyone has had a zillion times). -

Tarrasque

31

Tarrasque

31

This is a matter of principle vs practice again. Anything that can have any causal effect on something else is in principle capable of communicating with it, even if in practice they have no conventional obvious communication ability. (There are some amazing hacks that can get information off of computers not connected to any network, or monitor speech in a room with a computer with no microphone, etc, by using overlooked tiny effects between hardware and software, for example). If two things are causally isolated such that in principle no information about one of them can reach anything that can reach the other one, then from each of their perspectives the other seems not to exist at all, so they’re basically in separate universes.

You're stretching the ideas of "communication" and "information" too broadly to justify this. We could be dealing with conscious beings that have no bodily control and just float around non-autonomously. If there are no causal links between a being's thoughts and some capacity for action, it cannot communicate in principle. People in completely vegetative states are like this. You could imagine a being who is like a vegetative human, but still aware. Everyone on the planet could be this way. If two conscious, sedentary buoys bump into each other carried atop the tides, they have not just communicated. At least, no more than me being hit by a bus while the driver is asleep at the wheel is me communicating with the bus driver.

We necessarily imagine from some perspective or another though. If we imagine a world where we don’t exist, we imagine a world that doesn’t contain us as we really are, from some disembodied viewpoint. When we’re imagining the three men and the elephant, we’re imagining it from some viewpoint where we can observe all four of them. But if there isn’t actually any such viewpoint possible, because they’re all so completely isolated from each other, then all we should be imagining is each of their separate viewpoints, from which none of the others can ever seem to exist, nor the whole elephant, so what would it mean to claim that those things do exist, in some way that will never make any noticeable difference to anyone?

No, this is not necessarily the case. We can say "let's imagine a world where we don't exist, in any form, whatsoever. In such a world, my mother would have only three kids, the high school I attended would have one less student..." etc. The idea that we need to stipulate some kind of omniscient observer to talk about counterfactual situations is a unique proposition of your theory. I don't see any reason why it must be true.

"so what would it mean to claim that those things do exist, in some way that will never make any noticeable difference to anyone?"

It means precisely that. That they exist, but in a way that will never make any noticeable difference to anyone. Do you think that if no people existed to make empirical measurements of things, nothing would exist?

Conditional imperatives make perfect sense. It helps to remember that material implication is equivalent to a kind of disjunction: “if P then Q” is exactly equivalent to “Q or not P”. I can easily command someone to do Q or not do P, which is the logical equivalent of ordering them to do Q if they do P, or “if you do P, do Q”, without any kind of embedding trouble. It might look like there should be in the “if-then” form, but there’s clearly none in the “or” form which is identical to it.

It might also help to resolve the appearance of the problem if we factor the “be()” out to the whole conditional at once:

be(the saints being praised only if the demons being not praised)

or

be(the demons being not praised or the saints being not praised)

"If there is a beer, then get me one" makes sense, while "If get me a beer, then there is a beer" does not and might as well be gibberish. The disjunctive form of the latter is "There is a beer or not get me a beer." I wouldn't be so hasty to claim that conditional imperatives make "perfect sense."

"If the saints ought to be praised, then the demons ought not to be praised" does not seem equivalent to "if you praise the saints, then don't praise the demons." "You praise the saints" could be true while "the saints ought to be praised" is false.

If you still don't see how the Frege-Geach problem presents a challenge to the idea that moral statements are inherently imperative, I'll just leave you with an article that covers the problem and the solutions that have been attempted for it. Considering that you aren't super familiar with this problem, and it is oft considered the predominant challenge for views like yours, I'd suggest that you get more acquainted with it than just talking to me about it.

https://plato.stanford.edu/entries/moral-cognitivism/#EmbPro

If that were a problem, then every account of what people are doing with words would be subject to the same problem. If you take an ordinary indicative sentence to be reporting a fact, as you say, that’s still doing something, but in the antecedent of a conditional is it still doing that same fact-reporting? Whatever solution allows ordinary conditionals to work there, it should also work for whatever else other kinds of speech are doing, so long as there is a “truth-value” that can be assigned to that kind of speech, i.e. each such utterance is either a correct or incorrect utterance of that kind.