-

Tarrasque

31For those like me whose physicalist ontology cannot admit of some strange non-natural but nevertheless real moral facts, non-naturalism is a non-option. (This is also called the Argument from Queerness: wtf is a non-natural moral fact like?).

Tarrasque

31For those like me whose physicalist ontology cannot admit of some strange non-natural but nevertheless real moral facts, non-naturalism is a non-option. (This is also called the Argument from Queerness: wtf is a non-natural moral fact like?).

I think you may be overvaluing the argument from queerness. Do you have decisive reason to believe that only physical, natural facts exist? Take the true statement that there is an infinite amount of prime numbers. What is it true about? Is there something physical, or tangible, that you can present to me as an instantiation of the infinity of prime numbers? Mathematical truths are certainly not prescriptive, they are descriptive, but what do they describe?

The simplest answer would be "abstract objects." Do abstract objects exist? Well, if "P exists" just MEANS "P is physical," the answer is no. But, this may be an unnecessarily limiting conception of existence. Perhaps what it is for something to exist is, instead, for there to be a state of affairs that can ground factual claims about that thing. The infinity of the real numbers between 0 and 1 is greater than the infinity of the natural numbers. This statement is true. Is it spooky because it corresponds to a state of affairs that is not physical? I think not. -

Pfhorrest

4.6kIf we take “fact” to mean something broader than a description of reality, then I would agree that there are non-physical facts, and moral facts are among them. I don’t consider mathematical truths to be “facts” in the same narrower sense as descriptive truths about reality are, though; and I don’t consider abstract objects to “exist” in the same sense as physical objects do either. Math is neither descriptive nor prescriptive on my account, but equally applicable to either, and its truths are not made true by the existence (in the ordination sense) of some spooky abstract objects, any more than moral truths are made true by some kind of... moral stuff. They can both still be true those, for reasons other than accurately describing reality.

Pfhorrest

4.6kIf we take “fact” to mean something broader than a description of reality, then I would agree that there are non-physical facts, and moral facts are among them. I don’t consider mathematical truths to be “facts” in the same narrower sense as descriptive truths about reality are, though; and I don’t consider abstract objects to “exist” in the same sense as physical objects do either. Math is neither descriptive nor prescriptive on my account, but equally applicable to either, and its truths are not made true by the existence (in the ordination sense) of some spooky abstract objects, any more than moral truths are made true by some kind of... moral stuff. They can both still be true those, for reasons other than accurately describing reality. -

Tarrasque

31

Tarrasque

31

What differentiates the narrow sense and the broad sense as you speak of them, other than the fact that the narrow sense is physical and the broad sense is not? Mathematical statements make claims that are sometimes true. What does it mean for something to be true if not for the proposition to correspond to reality? Of course, I agree with you that neither mathematical nor moral facts correspond to something physical. But if all you mean by "the narrow sense of existence" IS the physical sense, then the moral non-naturalist does not disagree with you at all. The moral non-naturalist also agrees that moral facts are not physical.

If mathematical claims are not descriptive(describing a feature of reality), nor normative(counting in favor of an agent's doing or believing X), what kind of claims are they? To hold that moral claims are made true in virtue of "moral stuff," if we mean "stuff" in the usual sense, is naturalism. Non-naturalism would deny this, as do you, so I don't see where exactly you disagree with it.

Mathematical principles do appear to be a part of reality. At the very least, some mathematical principles appear to accurately describe physical reality, while others do not. One principle may provide a model for how planets orbit stars, while another may describe nothing that we see. But, the truth of both follows from the same axioms. They are both true for the same reasons. "Physical" versus "abstract" is a useful distinction, but is it the very same distinction as "real" and "not real?"

Does something seem so objectionable about referring to "mathematical reality," of which our present physical reality is only one of many possible subsets? We could imagine a world with different fundamental forces, or distinct physical composition, before we could imagine one with square circles and finite primes. The concept of a three-sided triangle corresponds to reality in a way that a four-sided triangle does not. When I say "a four-sided triangle does not exist," I am saying something MORE than that a four-sided triangle is merely not physical. After all, a three-sided triangle is also not physical, yet there is a difference between them.

Apologies for the wall of text, but I'm very interested in this topic. -

Enrique

845

Enrique

845

I'll give you an additional front of queerness to grapple with.

All of the following can mean "Bob ought to throw the ball":

"Bob is a big dick" (heckling fan)

"Bob knows" (coach)

"Bob, you damn idiot!" (teammate)

"We love Bob" (opposing team)

"wAAAAAAAAAAAAAAA!" (little sister)

"Who the hell cares" (nonfan)

"Bob shouldn't throw the ball!" (joking observer)

And this is about as unambiguous as real world meaning gets. How do you systematically account for all that context-variance and nuance of linguistic intention? (Me, I don't think its currently possible, which is why I glossed over theorizing modern language use while writing my own pet book project, but I'd be curious to see if you can generalize it) -

Tarrasque

31

Tarrasque

31

Not Pfhorrest, but I'll give my 2 cents. This isn't a problem unique to moral reasoning. Different people could use the utterances,

"The woman who gave birth to me"

"The nurse employed by me"

"The one who is scared of spiders"

"The person who stood in that Starbucks at 5:00 PM"

"Ma-ma!"

"La madre de este nino"

"Hey, YOU!"

All to refer to the same woman, my mother. We can attempt to remove ambiguity by providing further clarification. We can never fully resolve this problem, as a person can really attach any internal meaning to whatever words they like. But, most of the time, we seem to understand what other people mean and they seem to understand us. It's not the type of thing that can be or needs to be systematized: there is no hard and fast rule to figure out the meaning of words, one must just attempt to resolve it with their interlocutor. -

Pfhorrest

4.6kWhat differentiates the narrow sense and the broad sense as you speak of them, other than the fact that the narrow sense is physical and the broad sense is not? — Tarrasque

Pfhorrest

4.6kWhat differentiates the narrow sense and the broad sense as you speak of them, other than the fact that the narrow sense is physical and the broad sense is not? — Tarrasque

The broad sense is just the sense of “a statement that is correct” in any sense. The narrow sense is the sense of “a statement describing the world, that is correct”. Mathematical statements have implications about what can be real (which descriptions of the world can be correct), but they also have implications about what can be moral (which prescriptions of the world can be correct). They are more abstract than either description or prescription, and no more directly say what is real than they directly say what is moral.

If mathematical claims are not descriptive(describing a feature of reality), nor normative(counting in favor of an agent's doing or believing X), what kind of claims are they? — Tarrasque

They are statements of relations between ideas, formal logical inferences, without necessarily impressing a descriptive or prescriptive attitude toward those ideas.

A classic example of a formal logical inference is that from the propositions "all men are mortal" and "Socrates is a man" we can logically infer the proposition "Socrates is mortal". But, I hold, we could equally well infer from the propositions "all men ought to be mortal" and "Socrates ought to be a man" that "Socrates ought to be mortal". I say that it is really just the ideas of "all men being mortal" and "Socrates being a man" that entail the idea of "Socrates being mortal", and whether we hold descriptive, mind-to-fit-world attitudes about those ideas, or prescriptive, world-to-fit-mind attitudes about them, whether we're impressing or expressing those attitudes, even whether we're making statements or asking questions about them, does not affect the logical relations between the ideas at all.

Does something seem so objectionable about referring to "mathematical reality," of which our present physical reality is only one of many possible subsets? — Tarrasque

I do actually support something like this, in the form of mathematicism (or the mathematical universe hypothesis), but for me that’s really an extension of modal realism: any world that can possibly be, is, both in terms of configurations of a universe with the mathematical structure that ours has, and in terms of other mathematical structures. But claims of possibility is not made true by their accurately describing these other possible worlds, but rather by the internal consistency of the structures they posit, and the other possible worlds are limited by that same requirement of self-consistency, so they necessarily coincide.

I'll give you an additional front of queerness to grapple with. — Enrique

Not Pfhorrest, but I'll give my 2 cents. This isn't a problem unique to moral reasoning. — Tarrasque

You got it in one. Thanks. -

Tarrasque

31The broad sense is just the sense of “a statement that is correct” in any sense. The narrow sense is the sense of “a statement describing the world, that is correct”. Mathematical statements have implications about what can be real (which descriptions of the world can be correct), but they also have implications about what can be moral (which prescriptions of the world can be correct). They are more abstract than either description or prescription, and no more directly say what is real than they directly say what is moral.

Tarrasque

31The broad sense is just the sense of “a statement that is correct” in any sense. The narrow sense is the sense of “a statement describing the world, that is correct”. Mathematical statements have implications about what can be real (which descriptions of the world can be correct), but they also have implications about what can be moral (which prescriptions of the world can be correct). They are more abstract than either description or prescription, and no more directly say what is real than they directly say what is moral.

I see. I think that what is different between our ontologies must hinge on this notion of what it means for a proposition to be correct. What is your account of truth? I endorse a correspondence theory: P is true just in case P actually obtains. What does it mean for P to obtain? Well, that the real state of affairs is such that P. What else might it mean for a statement to be correct?

I'm interested in how you suggest that mathematics has moral implications. Could you elaborate on this idea?

A classic example of a formal logical inference is that from the propositions "all men are mortal" and "Socrates is a man" we can logically infer the proposition "Socrates is mortal". But, I hold, we could equally well infer from the propositions "all men ought to be mortal" and "Socrates ought to be a man" that "Socrates ought to be mortal". I say that it is really just the ideas of "all men being mortal" and "Socrates being a man" that entail the idea of "Socrates being mortal", and whether we hold descriptive, mind-to-fit-world attitudes about those ideas, or prescriptive, world-to-fit-mind attitudes about them, whether we're impressing or expressing those attitudes, even whether we're making statements or asking questions about them, does not affect the logical relations between the ideas at all.

Sure, those arguments are both of deductively valid form. I find that to be a strange usage of the word "ought," however. Ought claims are made about agents, prescribing that they should take a certain action or accept a particular belief. I wouldn't consider, for example, "all men ought to be made of atoms" to be an ought claim that makes sense. Ought implies can, and whether or not I am made of atoms, or am mortal, is far outside the jurisdiction of one's agency. You cannot provide a reason, normatively speaking, that I should be made of atoms. It's unclear what this could even consist in. You could provide a causal explanation, but of course, this is distinct.

I do actually support something like this, in the form of mathematicism (or the mathematical universe hypothesis), but for me that’s really an extension of modal realism: any world that can possibly be, is, both in terms of configurations of a universe with the mathematical structure that ours has, and in terms of other mathematical structures. But claims of possibility is not made true by their accurately describing these other possible worlds, but rather by the internal consistency of the structures they posit, and the other possible worlds are limited by that same requirement of self-consistency, so they necessarily coincide.

I am completely unfamiliar with modal realism, so this does not make a lot of sense to me. I think the best approach here is simply for me to try and paraphrase what you've said and wrap my head around it. I take what you're proposing to be something like this:

We often speak in terms of possible worlds, in many different senses. We can talk about physically possible worlds(consistent with the laws of physics), morally possible worlds(consistent with our world's moral truths), mathematically or logically possible worlds, and impossible worlds in every such sense. All logically and mathematically possible worlds(considering the relationship between logic and math, they may be one and the same set) actually exist. The only feature that can disqualify a world from existence is its instantiation of self-contradictory properties - these worlds are contained within the set of the logically and mathematically impossible worlds(a world where the law of non-contradiction is true, for example). As long as a world fulfills this single criterion, it is modally real. That is to say, we can conceive of it, discuss it meaningfully, and make true claims about it. Correct me if I'm mistaken in my understanding of your beliefs. -

Pfhorrest

4.6kWhat is your account of truth? I — Tarrasque

Pfhorrest

4.6kWhat is your account of truth? I — Tarrasque

A pragmatist one, especially hinging on the concepts of speech-acts (different types of which I plan on discussing over the course of this thread), where what makes a statement true depends entirely on what you're trying to do by making that statement. Describing and prescribing are different kinds of speech-actions, and so each have different criteria for doing them correctly, successfully, which when fulfilled make the statements true.

I'm interested in how you suggest that mathematics has moral implications. Could you elaborate on this idea? — Tarrasque

It cannot be correct to prescribe something that is logically contradictory, any more than it is correct to prescribe something that is logically contradictory. ("Ought" implies "can", as you say). Mathematics is about exploring the possibilities of different abstract structures, and the limits of that possibility limit what could be moral as much as they limit what could be real.

Ought claims are made about agents, prescribing that they should take a certain action or accept a particular belief. — Tarrasque

Not necessarily. We can very well say that everybody ought to have access to adequate food and water and shelter and medicine etc, and nobody ever ought to have to die; those would be good states of affairs. Them being good states of affairs has some implications on what actions agents ought to do, but it's not directly a statement about what anyone ought to do. We can likewise make prescriptive evaluations of the past: this or that atrocity or tragedy ought not have happened, which can mean that some people in the past ought not have done certain things, but even in that case, there's nothing anybody can do about it now, so we're not telling anybody at present what to do, we're just calling something that happened in the past bad.

If someone said that you ought to be made of atoms, that would mean to me that there was something better about being made of atoms than some alternative. Even if you have no control over it, that it ought to be the case just means that it's better for it to be the case than not.

I am completely unfamiliar with modal realism, so this does not make a lot of sense to me. I think the best approach here is simply for me to try and paraphrase what you've said and wrap my head around it. I take what you're proposing to be something like this: — Tarrasque

Your take is more or less correct, but if you're more interested in the details, I just wrote a lengthy post about it in another thread, and you can also read about modal realism more generally on Wikipedia or SEP, and more about the Mathematical Universe Hypothesis specifically on Wikipedia (I'm surprised Stanford doesn't have an article on it, or even on Tegmark generally, at all). -

Tarrasque

31Describing and prescribing are different kinds of speech-actions, and so each have different criteria for doing them correctly, successfully, which when fulfilled make the statements true.

Tarrasque

31Describing and prescribing are different kinds of speech-actions, and so each have different criteria for doing them correctly, successfully, which when fulfilled make the statements true.

Interesting take. I look forward to reading your expansion on it. It seems to capture some of our evaluative language well, while to describe other forms, it appears to be more of a stretch. You raised the excellent example yourself of historical moral evaluation. Since ought does imply can, I find it unlikely that by saying something like "The Holocaust was wrong," we are literally prescribing a course of action for the dead perpetrators. Rather, I believe that we are presenting an evaluation on the moral fact of the matter.

It cannot be correct to prescribe something that is logically contradictory, any more than it is correct to prescribe something that is logically contradictory. ("Ought" implies "can", as you say). Mathematics is about exploring the possibilities of different abstract structures, and the limits of that possibility limit what could be moral as much as they limit what could be real.

I agree with this. Well put(assuming one of those instances of "prescribe" was meant to read "describe.")

We can very well say that everybody ought to have access to adequate food and water and shelter and medicine etc, and nobody ever ought to have to die; those would be good states of affairs. Them being good states of affairs has some implications on what actions agents ought to do, but it's not directly a statement about what anyone ought to do.

I agree with what you are saying here, somewhat. Some states of affairs are better than others. It is sometimes the case that agents ought to act in ways that actualize these states of affairs. I could rephrase your statement as "everybody having access to adequate food and water is good." The fact that this is good provides agents with a defeasible reason to bring it about, in other words, ceteris paribus, they ought to act towards this end. You could describe a good state of affairs as either "a state that is good" or "a state that ought to be the case," but of the two, I think that the former does a better job at preserving what we mean when we use moral language. I think there are some circumstances where a state of affairs is good, but yet, it ought not to be the case - no individual or group ought to(or, more strongly, is obligated to) act in such a way as to bring it about. Note here that I believe oughts can apply to groups of agents just as well as single agents, take for instance, "The senate ought to pass law L."

I can't say I understand your opposition to non-naturalism. The argument from queerness(What would a moral fact even look like?) equally defeats all abstract facts. Yet, given your views on modal realism, logic, and mathematics, you have no issue dealing in objective facts that cannot be seen or touched. You seem not to consider them spooky. Do you consider the argument from queerness to be uniquely efficacious against moral facts for some reason? If all we can say about moral facts is that they have equally substantial grounding to other abstract facts(math, logic), that seems good enough to justify all the types of moral reasoning we like to use. -

Pfhorrest

4.6kI find it unlikely that by saying something like "The Holocaust was wrong," we are literally prescribing a course of action for the dead perpetrators. Rather, I believe that we are presenting an evaluation on the moral fact of the matter. — Tarrasque

Pfhorrest

4.6kI find it unlikely that by saying something like "The Holocaust was wrong," we are literally prescribing a course of action for the dead perpetrators. Rather, I believe that we are presenting an evaluation on the moral fact of the matter. — Tarrasque

I take those, prescriptions and evaluations, to be more or less the same thing: the impression of opinions with world-to-mind direction of fit. I guess this is as good a place as any to move on to that, which was to be the next part I wanted to discuss after impression and expression, but since nobody's commented on that yet and we're already talking about this, I may as well go on about that now.

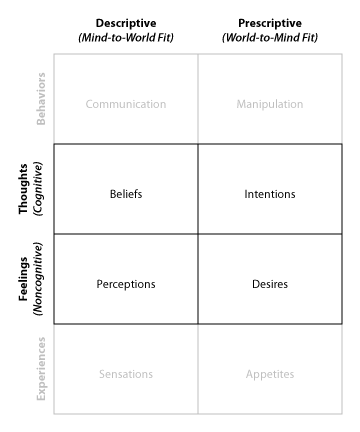

The short form of how I disagree with expressivism, to the motivations for which I am otherwise quite sympathetic, is that I hold moral utterances to not be expressing desires any more than descriptive utterances express perceptions. Rather, just as descriptive utterances impress beliefs, I would say that moral, prescriptive utterances impress intentions.

I've already elaborated on the difference between expression and impression above, but to elaborate on this difference between desires and intentions, and the analogous difference between perceptions and beliefs: In the field of moral psychology, there has been debate over the nature of "moral beliefs", which we can say are more or less the mental states communicated, in one way or another, by moral utterances. The two main sides of that debate are the Humeans and the Kantians. The Humeans hold that beliefs, properly speaking, that is to say cognitive states of mind that can possibly be true or false, are either about definitional relations of ideas to each other (as in logic and mathematics), or else about expectations of sensations or perceptions, and that everything else is mere sentiment or emotion. They agree with the argument from queerness that a "moral belief" would be a very strange thing, asking exactly what difference we would be to expect in our perception of reality if we held some "moral belief" instead of another. Finding no answer to that question apparent, they conclude that there actually are no such things as moral beliefs, only sentiments, emotions, feelings, specifically desires for things to be one way and not another. Kantians, on the other hand, bite the bullet of the argument from queerness, and affirm that there are such things as moral beliefs, that are capable of being true or false.

I find this Humeanism vs Kantianism to be a false dichotomy, and moral expressivism vs moral realism to be a false dichotomy as well. I think, like the Humean, that there are no such things as "moral beliefs" per se, and that moral utterances do not have any meaning to be found in some description of reality; but I also think, like the Kantian, that moral utterances do much more than just express desires incapable of being correct or incorrect. My position is not even that moral utterances impress desires, because I hold that desires are not the only mental state besides beliefs, and that beliefs are not the only cognitive mental states either, capable of being correct or incorrect. I use the term "opinion" to name the overarching category of mental states I am going to subdivide here, and I analyze an opinion as something I term an "attitude" toward something I term an "idea". The idea component of an opinion can be thought of as a mental picture of some possible, imaginable state of affairs, though it doesn't have to be literally visual: it is just the state of affairs that the opinion is about. But one can have different positions on different kinds of opinions about the same thing, and those different kinds of opinions about the same thing are what I mean by attitudes.

One important difference in attitude toward an idea is sometimes called "direction of fit", in reference to the terms "mind-to-world fit" and "world-to-mind fit". In a "mind-to-world fit", the mind (i.e. the idea) is meant to fit the world, in that if the two don't fit (if the idea in the mind differs from the world), then the mind is meant to be changed to fit the world better, because the idea is being employed as a representation of the world. In a "world-to-mind" fit, on the other hand, the world is meant to fit the mind (i.e. the idea), in that if the two don't fit (if the world differs from the idea in the mind), the world is meant to be changed to fit the mind better, because the idea is being employed as a guide for the world. It is the difference between a picture drawn as a representation of something that already exists, and a picture drawn as a blueprint of something that is to be brought into existence: it may be the same picture, but its intended purpose changes the criteria by which we judge it, and whether we judge the picture, or the thing it is a picture of, to be in error, should they not match. The clearest example of this difference in attitude that I can think of is that, given the idea of a world where some people kill other people, I expect most will agree that that idea is "right" in the sense that they agree with it as a description (most people, I expect, will agree that the world really is like that, and an idea of the world that doesn't feature such a thing is descriptively wrong), but simultaneously that it is "wrong" in the sense that they will disagree with it as a prescription (most people, I expect, will agree that the world morally oughtn't be like that — whatever "morally oughtn't" means to them, which we're getting to — and that a world that features such a thing is prescriptively wrong). Same idea, two different attitudes toward it: the world is that way, yes; but no, it oughtn't be that way. Two different opinions, but about the exact same thing, different not in the idea that they are about, but in the attitude toward that idea.

I take all kind of moral language, "good", "ought", "should", etc, to be conveying this kind of world-to-mind fit.

I agree with this. Well put(assuming one of those instances of "prescribe" was meant to read "describe.") — Tarrasque

Yes, good catch, and thanks. :-)

I think there are some circumstances where a state of affairs is good, but yet, it ought not to be the case - no individual or group ought to(or, more strongly, is obligated to) act in such a way as to bring it about. — Tarrasque

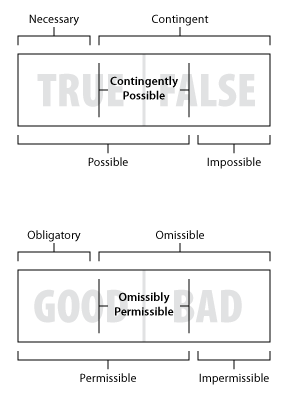

Yes I agree, when phrased in terms of obligation. Just as truth and falsehood don't capture the full range of alethic modal distinctions -- necessity, contingency, possibility, impossibility -- so too just goodness and badness don't capture the full range of deontic modal distinctions -- obligation, supererogatoriety, permissibility, and impermissibility.

Saying that someone "ought" to do something, or that something "should" be or that it would be "good", doesn't necessarily mean it is obligatory. It could very well be a supererogatory good.

I can't say I understand your opposition to non-naturalism. The argument from queerness(What would a moral fact even look like?) equally defeats all abstract facts. Yet, given your views on modal realism, logic, and mathematics, you have no issue dealing in objective facts that cannot be seen or touched. You seem not to consider them spooky. Do you consider the argument from queerness to be uniquely efficacious against moral facts for some reason? If all we can say about moral facts is that they have equally substantial grounding to other abstract facts(math, logic), that seems good enough to justify all the types of moral reasoning we like to use. — Tarrasque

I think it's important to clarify that I'm not opposed to moral semantics that are not moral naturalism, but rather to a specific stance on moral semantics called moral non-naturalism, which shares all of the same assumptions as naturalism -- cognitivism, descriptivism, robust realism -- and just disagrees on what kind of ontological things make moral claims cognitively true descriptions of reality. I object to moral naturalism for the same reasons the non-naturalist does, but I also object to most of the things they have in common, namely the presupposition that moral claims are trying to describe something about reality.

That would be the impression of an opinion with a mind-to-world direction of fit, and I think moral claims are impressing opinions with a world-to-mind direction of fit instead. This view is not robustly realist, but it's also not subjectivist, because it's not descriptivist at all. But it is still cognitivist, because I don't think that desires, non-cognitive opinions with world-to-mind fit, are the only kinds of opinions with world-to-mind fit, because there are differences in attitude besides just direction of fit, one of which, the one that makes the difference between cognitivism and non-cognitivism, I plan to discuss next, in a later post.

Correct ones of these non-descriptive but still cognitive opinions are not "facts" in the narrow sense, the sense that excludes mathematical claims. They could be called "facts" in a broader sense, but I find that that sense introduces unnecessary confusion, as "fact" seems to have inherently descriptivist connotations. The moral analogue of a "fact" is a "norm"; but NB that "norm" does not imply subjectivism, because "normal", "normative", etc, in their oldest senses, meant "correct" first and foremost, and it's only subjectivist assumptions that whatever everybody else is doing is correct that lead "normal" etc to take on the connotation of "what everyone else is doing". I don't mean it in that sense at all: a norm is just something that ought to be the case, exactly like a fact is something that is the case. -

Isaac

10.3kI’m going to ignore Isaac’s constant harping on that first criterion above and just move on to actual philosophy of language stuff. — Pfhorrest

Isaac

10.3kI’m going to ignore Isaac’s constant harping on that first criterion above and just move on to actual philosophy of language stuff. — Pfhorrest

Brilliant work of philosophical investigation "I'm going to ignore the part where there's some issue with one of my central claims and move on to discuss my conclusions assuming it to be the case"

What exactly is the point of your continued posting here if you're just going to ignore disputes? We're not your students, and this is not (as you've repeatedly been told) a platform for you to publicise your pet theories. If you want a one way conversation, write a fucking book, don't post on a public discussion forum and then complain when you get a public discussion. -

Echarmion

2.7kI agree. I'm arguing here against the opposite view, that moral decisions are (or can be) some kind of rational attempt to find what is 'right' by some pseudo-scientific method. — Isaac

Echarmion

2.7kI agree. I'm arguing here against the opposite view, that moral decisions are (or can be) some kind of rational attempt to find what is 'right' by some pseudo-scientific method. — Isaac

Well, my argument is that we managed to go from "intuitive empiricism" but controversial and variously flawed natural philosophies to scientific empiricism and scientific materialism.

Therefore, it doesn't strike me as prima facie absurd that we might go from intuitive moral judgement and controversial and flawed moral philosophy to some more universally accepted system of practical morality.

I didn't say we were. Just s significant one. Virtually every single person in the world from 2 year-olds to senile geriatrics, from psychopaths to saints, all believe in the external reality of the table in front of them, they all believe that it will behave in the same way for you as it does for them, and they all have done since we crawled out of the caves. The only exceptions are the insane and the mystical (possibly the same category).

Any form of communication, or social endeavour relies on these shared concepts. I can communicate with, or share an activity with, almost anyone on the planet at any point in time, based on the fact that there's a stable external world whose properties are not fixed by my mind.

I cannot make even the slightest progress on any communication or joint activity based on the notion that what is morally 'good' is that which feels hedonically 'good', because there is no such shared belief in this association. — Isaac

Yeah, that's a good point. We're certainly more reliant on a shared concept of external reality than we are on a shared meta-ethical theory.

But I wouldn't say that we cannot make "the slightest progress" on a joint idea of meta-ethics. I think you can use Hedonism, to take your example, as a fairly reliable heuristic to how people approach everyday questions. After all, that's the principle behind a basic economy. Both parties trade because they each get something they want more than what they trade away.

Of course, actual human relations are a lot more complex, but there is some evidence for shared meta-ethical frameworks.

Nor can I make any progress meta-ethically assuming that my assessment of 'the reasons' for believing the above position to be best, will be shared by many others - each person's assessment of any given collection of 'reasons' seems to also be different. — Isaac

Well there is a basic notion underlying a lot of philosophy that reason is a basic ability all humans have, and that therefore a correct reasoning will be understood and accepted by everyone.

If you don't share that notion, you'll inevitably end up with relativism in any field. Even the scientific method then isn't correct, it just happened to work until now.

The statement "An hedonic-based ethical systems is best because my assessment of the reasons for and against it is such that I find it the most compelling" is also mostly useless other than as a statement of the speaker's state of mind. It is only useful to the small group of people who (for whatever reason) trust that person's judgement for the modification of their own beliefs.

The statement "This bridge can only carry 8 Tons", however, is potentially useful to the entire world. Absolutely everyone would agree that if the limits of the materials tend, in tests, to break after being subjected to more than 8 Tons, that they will not magically act differently for different people, that no amount of belief on my part can make the bridge carry more, that at no point will the bridge suddenly act as if it's made of cheese...

The difference in the utility of different classes of statement may well only be one of degree, but the degree is hugely significant. — Isaac

Again, I want to point out that while today, almost everyone would agree that the question "will the bridge hold if I drive across it in this 8 ton truck" is answered via the scientific method, that wasn't always the case. Some other approaches include asking an oracle, offering the gods a sacrifice for safe passage, or ritually blessing the bridge. And people in the past did try those.

So while it seems evident from our modern perspective that the scientific method is simply and obviously correct and that it has so much more utility than any moral philosophy as to be an entirely different kind of idea, a look at history imo shows that it's not so simple. For most of history, natural philosophy and moral philosophy were not much different. That we managed to "solve" the former doesn't make it less likely that the latter can also be solved. -

Isaac

10.3kWell, my argument is that we managed to go from "intuitive empiricism" but controversial and variously flawed natural philosophies to scientific empiricism and scientific materialism. — Echarmion

Isaac

10.3kWell, my argument is that we managed to go from "intuitive empiricism" but controversial and variously flawed natural philosophies to scientific empiricism and scientific materialism. — Echarmion

I see. I think though that such progress was not really about metaphysical commitments as much as expanding the line of answerable questions. During the era of, say, religious beliefs about reality, no one built ships according to how a priest suggested, no one sought advice from the clergy as to whether their table might bear their cup. Religious explanations only had any power where empirical answers were difficult. OK, there's always a couple of decades of 'culture wars' as the new areas of investigation impinge on previously religious territory, but by and large it's still a question of adopting empiricism everywhere it is possible, all that changes is the fields it is possible to draw evidence from.

Therefore, it doesn't strike me as prima facie absurd that we might go from intuitive moral judgement and controversial and flawed moral philosophy to some more universally accepted system of practical morality. — Echarmion

And 2000 years of complete and utter failure to do so hasn't dampened your enthusiasm any?

I wouldn't say that we cannot make "the slightest progress" on a joint idea of meta-ethics. I think you can use Hedonism, to take your example, as a fairly reliable heuristic to how people approach everyday questions. — Echarmion

I agree. I didn't say one couldn't use it in some circumstances. The argument is that it does not cover all that we refer to when we talk about morality, and that we could not, even in circumstances where it might apply, appeal to any shared axioms to persuade dissenters of this.

Well there is a basic notion underlying a lot of philosophy that reason is a basic ability all humans have, and that therefore a correct reasoning will be understood and accepted by everyone. — Echarmion

Again is refer you to the 2000 years of abject failure to agree on anything outside of empirical knowledge. If reason was a basic ability and its recognition universal, then why so much disagreement over the validity of reasons? -

Pfhorrest

4.6kBrilliant work of philosophical investigation "I'm going to ignore the part where there's some issue with one of my central claims and move on to discuss my conclusions assuming it to be the case" — Isaac

Pfhorrest

4.6kBrilliant work of philosophical investigation "I'm going to ignore the part where there's some issue with one of my central claims and move on to discuss my conclusions assuming it to be the case" — Isaac

The fact that YOU don’t agree with one point isn’t reason to halt the entire discussion that wasn’t even supposed to be about that point just to waste pages and pages on pointlessly trying to convince YOU of something most people don’t need convincing of.

Moral nihilism or relativism (same thing really) are far, far from universally accepted, and the common objection to numerous of the meta-ethical theories surveyed in the OP is that they require moral nihilism or relativism. The point of this thread is to explore the possibilities a meta-ethics that is not vulnerable to the common objections to all those ones surveyed in the OP. That you are unconvinced by one of those objections shouldn’t stop the whole rest of the discussion.

What even is your meta-ethics anyway? Expressivism? -

Isaac

10.3kThe fact that YOU don’t agree with one point isn’t reason to halt the entire discussion that wasn’t even supposed to be about that point — Pfhorrest

Isaac

10.3kThe fact that YOU don’t agree with one point isn’t reason to halt the entire discussion that wasn’t even supposed to be about that point — Pfhorrest

Fine. The polite way of achieving that is to say something like "let's come back to that, I want to discuss other things", not snipe at someone for 'harping on' as if objection to your position was an irritating side-track.

waste pages and pages on pointlessly trying to convince YOU of something most people don’t need convincing of.... Moral nihilism or relativism (same thing really) are far, far from universally accepted — Pfhorrest

So now the majority does make right? Your meta-philosophy is very mixed.

The point of this thread is to explore the possibilities a meta-ethics that is not vulnerable to the common objections to all those ones surveyed in the OP. — Pfhorrest

If what you're discussing here really is new and not something that philosophers before you have already thought of and dismissed, then you need to publish. Do you even realise the monumental unlikelihood of you having come up with some solution that 2000 years of moral philosophers haven't?

That you are unconvinced by one of those objections shouldn’t stop the whole rest of the discussion. — Pfhorrest

It's not. The rest of the discussion can carry on and still address the issues I raise, you're having several discussions at once already. You're not obliged to answer, you're quite welcome to chair your own discussion in whatever way you see fit, but there's no reason to treat those who disagree with you as an irritant. It just makes you come across as dogmatic and proselytising, rather than discursive. -

Pfhorrest

4.6kSo no the majority does make right? Your meta-philosophy is very mixed. — Isaac

Pfhorrest

4.6kSo no the majority does make right? Your meta-philosophy is very mixed. — Isaac

Majority doesn’t make right, but it shows that this isn’t some crazy new idea of mine that needs to be conclusively proven before we can move on. It’s a reasonable background assumption that can be taken as a premise for another conversation, not something that the entire conversation has to be about.

If what you're discussing here really is new and not something that philosophers before you have already thought of and dismissed, then you need to publish. Do you even realise the monumental unlikelihood of you having come up with some solution that 2000 years of moral philosophers haven't? — Isaac

What do you think is appropriate discussion material for a philosophy forum? Are we only allowed to talk about things that other philosophers have already said? No original thoughts allowed?

I don’t know for sure how original my thoughts are. I’m passingly familiar with a few similar ones. I hope to find out more about any similar thoughts and the arguments about them that have already been had, if any, by discussing them in a public place like this. I don’t have the time = money to conduct an exhaustive professional literature review to be absolutely sure of where my thoughts fit in the ongoing professional dialogue, and I don’t have the accredited nor the time = money to get it to even be considered by a professional publication.

What else is someone who has as far as they can tell original thoughts supposed to do in such a situation, besides talk about them with other amateurs? -

Isaac

10.3kMajority doesn’t make right, but it shows that this isn’t some crazy new idea of mine that needs to be conclusively proven before we can move on. — Pfhorrest

Isaac

10.3kMajority doesn’t make right, but it shows that this isn’t some crazy new idea of mine that needs to be conclusively proven before we can move on. — Pfhorrest

I'm not seeing the difference. If majority agreement does not act as any kind truth-maker then how is it that ideas which have majority support can be taken as a reasonable background assumption? From what consequence of majority agreement does it derive its reasonableness if not some greater liklihood of being right?

What else is someone who has as far as they can tell original thoughts supposed to do in such a situation, besides talk about them with other amateurs? — Pfhorrest

Listen with some moderate humility to what those others have to say where you've no reason other than your personal disagreement to dismiss them. -

Kenosha Kid

3.2kYet that seems vulnerable to the same Euthyphro-esque attacks as Divine Command Theory: is what culture says is good good just because they say it is? (if so that seems rather arbitrary and unjustified) or do they say it's good because it actually is? (if so then it's not them saying it that makes it good and we're back to where we started: what actually makes it good?). Subjectivism also seems to undermine a lot of the point of cognitivism in the first place: if everybody's differing moral claims are all true relative to themselves, then it doesn't seem like any of them are actually true at all, they're just different opinions, none more right or wrong than the others. — Pfhorrest

Kenosha Kid

3.2kYet that seems vulnerable to the same Euthyphro-esque attacks as Divine Command Theory: is what culture says is good good just because they say it is? (if so that seems rather arbitrary and unjustified) or do they say it's good because it actually is? (if so then it's not them saying it that makes it good and we're back to where we started: what actually makes it good?). Subjectivism also seems to undermine a lot of the point of cognitivism in the first place: if everybody's differing moral claims are all true relative to themselves, then it doesn't seem like any of them are actually true at all, they're just different opinions, none more right or wrong than the others. — Pfhorrest

This reminds of Dennett's dig about "real magic": "real magic" isn't real, doesn't exist; the magic that's real (that you can see on stage) isn't "real magic". He was making this in response to dualists who insist that, whatever scientists discover about the relationship between brain and consciousness, i.e. the consciousness that's real, that isn't "real consciousness".

"is what culture says is good good..?" is another example: it insists upon the existence of an external measure of the good of a cultural good. Most of the difficulties described in the OP arise from that insistence, since they deal with "real morality" rather than morality in the real world. -

Pfhorrest

4.6kI'm not seeing the difference. If majority agreement does not act as any kind truth-maker then how is it that ideas which have majority support can be taken as a reasonable background assumption? From what consequence of majority agreement does it derive its reasonableness if not some greater liklihood of being right? — Isaac

Pfhorrest

4.6kI'm not seeing the difference. If majority agreement does not act as any kind truth-maker then how is it that ideas which have majority support can be taken as a reasonable background assumption? From what consequence of majority agreement does it derive its reasonableness if not some greater liklihood of being right? — Isaac

It’s a discursively thing at issue here, not a strictly logical one. If one were to propose to the pre-Copernican world something that takes for granted that the Earth revolves around the sun, one would first have to get anybody at all on board with that presupposition before one could move on to the actual topic. But that same discussion today doesn’t first have to established heliocentrism: we can take it for granted that most people just assume it and go on from there, and argue for heliocentrism with the doubters elsewhen, but never telling them to just accept it because the majority does.

I suddenly shifted away from debating you when Echarmion’s comment reminded me that I didn’t come here to discuss the merits of heliocentrism, I came to discuss some ideas about space travel that take heliocentrism for granted, and then foolishly got bogged down debating a geocentist instead of getting on with the actual topic.

Listen with some moderate humility to what those others have to say where you've no reason other than your personal disagreement to dismiss them. — Isaac

I have reasons for disagreement, that I’ve repeatedly shared. And I do listen carefully to everyone, looking for anything new I haven’t already considered. There just isn’t a lot of that to be found, so most things I listen to are things I’ve already heard and already have reasons not to agree with. Which I then share. -

Pfhorrest

4.6kSo if gods actually existed, would divine command theory be a fine meta-ethics, and the Euthyphro a bad argument, because “is what the gods command actually good?” is asking for “real magic” when the priests are showing you the only “magic“ there actually is, these commands from the gods?

Pfhorrest

4.6kSo if gods actually existed, would divine command theory be a fine meta-ethics, and the Euthyphro a bad argument, because “is what the gods command actually good?” is asking for “real magic” when the priests are showing you the only “magic“ there actually is, these commands from the gods?

How would that mesh with your bio-social relativism? The body and your society say that one thing is good, the gods (remember we’re imagining a world where they’re real) say another thing is. Which should we listen to? Why? Which is actually good? What should we actually do? Is that a meaningless question?

Even within your bio-social relativism, what if the body and society give different directives? Which should we listen to and why? -

Kenosha Kid

3.2kSo if gods actually existed, would divine command theory be a fine meta-ethics, and the Euthyphro a bad argument, because “is what the gods command actually good?” is asking for “real magic” when the priests are showing you the only “magic“ there actually is, these commands from the gods? — Pfhorrest

Kenosha Kid

3.2kSo if gods actually existed, would divine command theory be a fine meta-ethics, and the Euthyphro a bad argument, because “is what the gods command actually good?” is asking for “real magic” when the priests are showing you the only “magic“ there actually is, these commands from the gods? — Pfhorrest

That wasn't the easiest to parse, but I think I can safely say yes: if gods were the actual phenomena underlying our morality, it would be meaningless to ask if what the gods command is itself good. And if that seems an absurd conclusion, check the quality of the proposition :rofl: I believe this is commonly espoused among the devout, and was the basis of Kierkegaard's "Knight for God" notion in which the good of a command from God is always good, even if it seems evil to those around you.

Even within your bio-social relativism, what if the body and society give different directives? Which should we listen to and why? — Pfhorrest

Yes, body and society conflict. The example I gave before was Abu Ghraib, in which soldiers who felt that what they were doing was very wrong did it anyway because that's what the group did, which is a powerful incentive (fear of retribution or outcasting are long-standing socio-biological fears, presumably meant do deter us from antisocial behaviour - boy, did that backfire). This is one of the effects I see in living in large, co-mingled groups: cultures become diverse, leaving the field open for a power-grab, in this case as in many by violent thugs.

In smaller groups, culture is more homogeneous, making it unlikely that you will encounter someone cultural different from yourself, so the problem should not arise... in principle.

I've just realised I am rewriting Genesis! Small social groups being the natural state of moral ignorance allowed by homogeneity, with our fall from grace related to an awareness of good and evil thrust upon us. If I can just work in a snake... -

Isaac

10.3kthat same discussion today doesn’t first have to established heliocentrism: we can take it for granted that most people just assume it and go on from there — Pfhorrest

Isaac

10.3kthat same discussion today doesn’t first have to established heliocentrism: we can take it for granted that most people just assume it and go on from there — Pfhorrest

So, from where are you getting this idea that moral realism is the equivalent of heliocentrism. Phil Papers Survey has 56.4% lean toward moral realism. A recent survey in America has only 35% believe in objective moral truth. I don't know what sources you're using to arrive at this idea that non-relativist moral truth is taken for granted by most people so much so that discussing any alternative would be like proving heliocentrism.

I do listen carefully to everyone — Pfhorrest

I didn't say 'carefully' I said 'with humility'. -

Tarrasque

31First, I want to commend you for the substantial time and effort you have clearly put into philosophizing. You have managed to put something together which is, on the whole, innovative, and impressive. As to whether or not it does the best job among competing theories by metrics of truth and explanatory power, I hold my reservations. But, I expect a good time investigating it.

Tarrasque

31First, I want to commend you for the substantial time and effort you have clearly put into philosophizing. You have managed to put something together which is, on the whole, innovative, and impressive. As to whether or not it does the best job among competing theories by metrics of truth and explanatory power, I hold my reservations. But, I expect a good time investigating it.

I find this Humeanism vs Kantianism to be a false dichotomy, and moral expressivism vs moral realism to be a false dichotomy as well. I think, like the Humean, that there are no such things as "moral beliefs" per se, and that moral utterances do not have any meaning to be found in some description of reality; but I also think, like the Kantian, that moral utterances do much more than just express desires incapable of being correct or incorrect.

"John believes that abortion is impermissible, while I believe abortion is permissible." This is a statement which makes sense, and would not be strange to hear. In a sentence such as this, do you hold that the use of the word "believes" is a category error? If moral utterances do not express beliefs, how can the above be true or false? Must it be false? How would you reform this sentence to preserve its meaning?

Furthermore, atomic moral sentences can be used to construct valid arguments. Example,

P1. Stealing is wrong.

P2. If stealing is wrong, then getting your little brother to steal is wrong.

C. Getting your little brother to steal is wrong.

If moral statements express beliefs about matters of fact, this is no different from a common variety modus ponens. Otherwise, there is something strange going on here. If I understand you correctly, when I utter "stealing is wrong," I am impressing on my audience some imperative not to steal. This normative evaluation is capable of being correct or incorrect, by your account, but the meaning of the sentence is nonetheless to impress a particular intent. With this in mind, let us semantically dissect the above modus ponens.

In P1, the atomic sentence "stealing is wrong" impresses an intent by its very utterance. This is due to the type of speech-act you claim it is. In a sense, the statement "stealing is wrong" cannot be disentangled from this force of impression.

Yet, in P2, I state that "IF stealing is wrong," then this other thing is wrong. In this case, I am not committing to impress anything on my audience. The meaning of "stealing is wrong" as an atomic sentence appears different than its use as the antecedent of a conditional. This is problematic for the validity of moral modus ponens. Your theory will have to account for this in some way to be successful.

One important difference in attitude toward an idea is sometimes called "direction of fit", in reference to the terms "mind-to-world fit" and "world-to-mind fit". In a "mind-to-world fit", the mind (i.e. the idea) is meant to fit the world, in that if the two don't fit (if the idea in the mind differs from the world), then the mind is meant to be changed to fit the world better, because the idea is being employed as a representation of the world. In a "world-to-mind" fit, on the other hand, the world is meant to fit the mind (i.e. the idea), in that if the two don't fit (if the world differs from the idea in the mind), the world is meant to be changed to fit the mind better, because the idea is being employed as a guide for the world. It is the difference between a picture drawn as a representation of something that already exists, and a picture drawn as a blueprint of something that is to be brought into existence: it may be the same picture, but its intended purpose changes the criteria by which we judge it, and whether we judge the picture, or the thing it is a picture of, to be in error, should they not match.

Alright, I'm following so far. Whether or not this conception is accurate, I like it a lot.

given the idea of a world where some people kill other people, I expect most will agree that that idea is "right" in the sense that they agree with it as a description (most people, I expect, will agree that the world really is like that, and an idea of the world that doesn't feature such a thing is descriptively wrong), but simultaneously that it is "wrong" in the sense that they will disagree with it as a prescription (most people, I expect, will agree that the world morally oughtn't be like that — whatever "morally oughtn't" means to them, which we're getting to — and that a world that features such a thing is prescriptively wrong). Same idea, two different attitudes toward it: the world is that way, yes; but no, it oughtn't be that way. Two different opinions, but about the exact same thing, different not in the idea that they are about, but in the attitude toward that idea.

I take all kind of moral language, "good", "ought", "should", etc, to be conveying this kind of world-to-mind fit.

To this point, I will simply offer an alternative explanation. I don't think that "same idea, two different attitudes toward it" captures what is going on in this case. Rather, I hold that these are two distinct ideas. One is that people do murder, the other is that people ought to murder. Somebody could agree or disagree(correctly or incorrectly) with either, in any combination. In accordance with the is-ought distinction, my agreement with one cannot logically follow merely from my agreement from the other.

I find it interesting that you classify "ought" and "should" as distinctly moral language. I have more to say about this below.

Saying that someone "ought" to do something, or that something "should" be or that it would be "good", doesn't necessarily mean it is obligatory. It could very well be a supererogatory good.

I was thinking of supererogatory action when I typed that out, so I'm glad you caught it. While you are correct that "he is obligated to X" is much normatively weightier than "he ought to X," I still think that using "ought" to refer to supererogatory acts is a butchery of our use of the word. If you were to tell me "everybody on the planet ought to live life in constant ecstasy" or "you ought to sacrifice your life to save mine," I would strongly disagree with you. If you then told me that when you used "ought," you really just meant that these things would be good, I would come to agree with you, still believing that you had originally misused the word "ought." I will provide more reasons why I think this below.

Correct ones of these non-descriptive but still cognitive opinions are not "facts" in the narrow sense, the sense that excludes mathematical claims. They could be called "facts" in a broader sense, but I find that that sense introduces unnecessary confusion, as "fact" seems to have inherently descriptivist connotations. The moral analogue of a "fact" is a "norm"; but NB that "norm" does not imply subjectivism, because "normal", "normative", etc, in their oldest senses, meant "correct" first and foremost, and it's only subjectivist assumptions that whatever everybody else is doing is correct that lead "normal" etc to take on the connotation of "what everyone else is doing". I don't mean it in that sense at all: a norm is just something that ought to be the case, exactly like a fact is something that is the case.

Alright, this is the place where I want to talk about reasons and rationality. In all your theorizing on normativity thus far, I have only seen you touch on moral normativity. This is not the only type. I can make claims like:

"You should stop smoking."(Prudential ought)

"You ought to proportion your belief to the evidence."(Rational ought)

"You ought not to beat your wife."(Moral ought)

"You ought to do the thing that you have the most reason to do."

I would like to touch on that last example a little more. "You ought to do the thing that you have the most reason to do." If you are anything like me, you find that incredibly intuitive. I have come to believe that it is essentially the definition of ought. The thing that a person ought to do is the thing that they have the most reason to do. Moral reasons are a type of reason, but often the thing that we have the most moral reason to do is not the thing that we have the most total reason to do(ergo supererogatory actions).

Since moral oughts are not the only type of oughts we use, I am surprised to not see theorizing on broader normativity in your work. Questions like "Is X rational" or "Is P a good reason to Q" need to be answerable, or at least explainable, by any plausible theory of normativity. -

Pfhorrest

4.6kFirst, I want to commend you for the substantial time and effort you have clearly put into philosophizing. You have managed to put something together which is, on the whole, innovative, and impressive. As to whether or not it does the best job among competing theories by metrics of truth and explanatory power, I hold my reservations. But, I expect a good time investigating it. — Tarrasque

Pfhorrest

4.6kFirst, I want to commend you for the substantial time and effort you have clearly put into philosophizing. You have managed to put something together which is, on the whole, innovative, and impressive. As to whether or not it does the best job among competing theories by metrics of truth and explanatory power, I hold my reservations. But, I expect a good time investigating it. — Tarrasque

Thanks! I'm looking forward to this conversation too (and enjoying it so far already).

"John believes that abortion is impermissible, while I believe abortion is permissible." This is a statement which makes sense, and would not be strange to hear. In a sentence such as this, do you hold that the use of the word "believes" is a category error? If moral utterances do not express beliefs, how can the above be true or false? Must it be false? How would you reform this sentence to preserve its meaning? — Tarrasque

Natural language is inherently sloppy, and I don't set out to admonish anyone for casually using "belief" to refer to their moral opinions. But because "belief" has descriptivist connotations, especially in the Kantian vs Humean context, I try to be careful to avoid it myself. I say instead that moral utterances impress (and so implicitly also express; you caught the part about impression vs expression earlier?) intentions. And I say that intentions can be objectively correct or incorrect ("true" and "false" also frequently have descriptivist connotations, so I try to avoid them myself, but recognize their casual use). Both intentions and beliefs are subsets of what I call "thoughts" (as distinct from "feelings", "experiences", and other mental states), so the simplest rephrasing of the above would just be to say "John thinks ... while I think ..." instead, since the permissible/impermissible already carry subtler imperative force.

(I want to launch into the next thing I wanted to bring up, thoughts vs feelings or "order of opinion" here, but I don't want to break the flow of this response so I'll put that at the bottom instead).

In general, when not dealing with modalities like that, I would most strictly phrase things as "so-and-so believes such-and-such (to be the case)" for descriptions and "so-and-so intends such-and-such (to be the case)" for prescriptions.

Furthermore, atomic moral sentences can be used to construct valid arguments. Example,

P1. Stealing is wrong.

P2. If stealing is wrong, then getting your little brother to steal is wrong.

C. Getting your little brother to steal is wrong.

If moral statements express beliefs about matters of fact, this is no different from a common variety modus ponens. Otherwise, there is something strange going on here. If I understand you correctly, when I utter "stealing is wrong," I am impressing on my audience some imperative not to steal. This normative evaluation is capable of being correct or incorrect, by your account, but the meaning of the sentence is nonetheless to impress a particular intent. With this in mind, let us semantically dissect the above modus ponens.

In P1, the atomic sentence "stealing is wrong" impresses an intent by its very utterance. This is due to the type of speech-act you claim it is. In a sense, the statement "stealing is wrong" cannot be disentangled from this force of impression.

Yet, in P2, I state that "IF stealing is wrong," then this other thing is wrong. In this case, I am not committing to impress anything on my audience. The meaning of "stealing is wrong" as an atomic sentence appears different than its use as the antecedent of a conditional. This is problematic for the validity of moral modus ponens. Your theory will have to account for this in some way to be successful. — Tarrasque

This is why I brought up the "Socrates being mortal" example before.

In my system of logic, I propose that rather than treating a statement like "All men are mortal" as one proposition and a statement like "All men ought to be mortal" as another, completely unrelated proposition, we instead take the idea that they have in common, "all men being mortal", and wrap that in a function that conveys what we wish to communicate about some attitude toward that idea. For example we might write there-is(all men being mortal) to mean "all men are mortal", and be-there(all men being mortal) to mean "all men ought to be mortal"; and generally, write there-is(S) and be-there(S) for the equivalent descriptive and prescriptive statements about the idea of some state of affairs S, whatever S is. We might wish to use shorter names for the functions, like simply is() and be(), or some other names entirely; I am merely using the indicative and imperative moods of the copula verb "to be" to capture the descriptive and prescriptive natures of the respective functions.

So in your modus ponens, the logical relationship is actually between "stealing happening" and "getting your little brother to steal": getting your little brother to steal entails stealing happening. So if it-ought-to-be-the-case-that-there-is(not(stealing happening)), and (getting your little brother to steal) entails (stealing happening), then it-ought-to-be-the-case-that-there-is(not(getting your little brother to steal)).

You can replace it-ought-to-be-the-case-that-there-is with it-is-the-case-that-that-there-is and you get the same logical relations, just with descriptive force instead of prescriptive force.

Alright, I'm following so far. Whether or not this conception is accurate, I like it a lot. — Tarrasque

Thanks again!

To this point, I will simply offer an alternative explanation. I don't think that "same idea, two different attitudes toward it" captures what is going on in this case. Rather, I hold that these are two distinct ideas. One is that people do murder, the other is that people ought to murder. Somebody could agree or disagree(correctly or incorrectly) with either, in any combination. In accordance with the is-ought distinction, my agreement with one cannot logically follow merely from my agreement from the other. — Tarrasque

I agree completely, and I didn't mean to suggest otherwise. My point is just that the opinion "people do murder" and the opinion "people ought to murder" can both be decomposed into some attitude or another toward the idea of people murdering: one descriptive attitude (the idea does happen) and one prescriptive attitude (the idea should happen). You can totally have different views on each of those full opinions: agree that it does happen, disagree that it should happen. That was the point of using that example, that for most people, I expect their agreement on opinions about the same idea (people murdering) will be opposite for those two kinds of attitude: they'll agree that it does, disagree that it should. Thus illustrating what "people do murder" and "people ought to murder" have in common (the idea of people murdering), and different (the attitudes toward that idea).

I was thinking of supererogatory action when I typed that out, so I'm glad you caught it. While you are correct that "he is obligated to X" is much normatively weightier than "he ought to X," I still think that using "ought" to refer to supererogatory acts is a butchery of our use of the word. If you were to tell me "everybody on the planet ought to live life in constant ecstasy" or "you ought to sacrifice your life to save mine," I would strongly disagree with you. If you then told me that when you used "ought," you really just meant that these things would be good, I would come to agree with you, still believing that you had originally misused the word "ought." I will provide more reasons why I think this below. — Tarrasque

I see this as just another example of natural language being sloppy. I agree that in some cases "ought" will carry connotations of obligation, rather than merely supererogatory good, and that being blithe to those differences will result in miscommunication. But that's something to sort out rhetorically, and doesn't have much to do with the actual underlying logic I'm on about here.

Alright, this is the place where I want to talk about reasons and rationality. In all your theorizing on normativity thus far, I have only seen you touch on moral normativity. This is not the only type. I can make claims like:

"You should stop smoking."(Prudential ought)

"You ought to proportion your belief to the evidence."(Rational ought)

"You ought not to beat your wife."(Moral ought)

"You ought to do the thing that you have the most reason to do."

I would like to touch on that last example a little more. "You ought to do the thing that you have the most reason to do." If you are anything like me, you find that incredibly intuitive. I have come to believe that it is essentially the definition of ought. The thing that a person ought to do is the thing that they have the most reason to do. Moral reasons are a type of reason, but often the thing that we have the most moral reason to do is not the thing that we have the most total reason to do(ergo supererogatory actions).

Since moral oughts are not the only type of oughts we use, I am surprised to not see theorizing on broader normativity in your work. Questions like "Is X rational" or "Is P a good reason to Q" need to be answerable, or at least explainable, by any plausible theory of normativity. — Tarrasque

I see prudential oughts as boiling down to a kind of moral ought. Taking care of yourself is a kind of moral good -- not necessarily an obligatory one, but still a moral one even if only supererogatory, you matter just like everybody else matters -- and instrumentally seeing to moral ends is still a kind of moral good. So you should stop smoking because if you don't you'll probably suffer and die, and people suffering and dying is bad.

Rational "oughts" I think can be better rephrased descriptively. "If you proportion your belief to the evidence your belief is more likely to be accurate." You might ask "but should beliefs be accurate?" and the answer to that is a trivial yes, because believing something just is thinking it's an accurate description of reality. If you didn't care to have an accurate description of reality, you wouldn't bother forming beliefs.

I agree completely that "you ought to do the thing that you have the most reason to do" is incredibly intuitive, but I think that a reason to do something just is a moral imperative; largely because of how prudential self-care collapses to moral normativity on my account.

I do have a lot more thoughts on how to justify both beliefs and intentions, which I think is more of the rationality-normativity you're thinking of. But that would get way outside the scope of this thread on semantics. I do intend to start threads on them later, and I hope you'll join in then.

In the meantime, here's the bit about order of opinion (thoughts vs feelings) I cut out from above for flow:

The difference in attitude alone isn't enough to account for what I mean by "intention" as distinct from "desire", which both have the same direction of fit, world-to-mind. To explain that, I need to first elaborate on differences in attitude between opinions with the same mind-to-world fit. More fundamental than opinions are experiences, and an experiences with mind-to-world fit are called "sensations". These are the raw input from our senses, free from any interpretation: the contents of a sensation are colors of light, pitches of sound, and so on, not yet shapes or words. In contrast, the simplest opinions with mind-to-world fit, first-order or irreflexive opinions of that type, are called "perceptions". These are interpretations of that raw sense-data into more abstract representations, but still of the same idea. (An analogy can be made here between raster and vector computer graphics formats, where a raster format stores an array of colored pixels and any shapes that appear in them are merely inferred by human viewers out of the patterns in those pixels; while a vector format stores abstract representations of exact shapes directly, which can then be rendered as arrays of pixels for display. The human viewer senses something like the array of pixels with their eyes, but then in perceiving shapes in the image, they are essentially "vectorizing" the image in their own mind). Further still, higher-order or reflexive opinions with mind-to-world fit are called "beliefs", and I hold that the distinguishing feature of beliefs is that they "objectify" what have thus far been completely subjective opinions, because they are reflexive in attitude, being capable of casting judgement on other opinions with the same content: one can disbelieve one's perceptions, or judge someone else's perception to be wrong as well. A belief is a perception that has been questioned (however thoroughly) and found (however correctly) to be the correct interpretation of sensations, the correct picture to use as a representation of the world, the correct opinion with mind-to-world fit.

I hold that there are analogues to all of those, but with world-to-mind fit instead. I call experiences with world-to-mind fit "appetites". These are composed of the raw inputs of things like pain, hunger, thirst, and so on. While sensations are the experiences that make us feel, on a raw unexamined level, like the world is some way, appetites are those experiences that make us feel, on a raw unexamined level, like the world ought to be some way. I visualize this as building two images, two ideas, in our minds: one of them a picture of the world as it is, meant to serve as a representation of the world, meant to fit the world; and the other of them a picture of the world as it ought to be, meant to serve as a guide for the world, meant for the world to fit. Sensations are those experiences that feed into that first picture, and appetites are those experiences that feed into that second picture. In contrast to those uninterpreted appetites, the simplest opinions with world-to-mind fit, first-order or irreflexive opinions of that type, are called "desires", like the expressivists and Humeans are all about, which I hold to differ from appetites in the same way that perceptions differ from sensations: desires are interpretations of appetites, and while an appetite may have as its content the feeling of, for example, hunger pains, the desire that is interpreted from that will have as its content instead, for example, to eat a burrito; just as sensations may contain patterns of light while perceptions instead contain shapes. And lastly, higher-order or reflexive opinions with world-to-mind fit I call "intentions", and I hold that the distinguishing feature of intentions is that they "objectify" what have thus far been completely subjective opinions, because they are reflexive in attitude, being capable of casting judgement on other opinions with the same content: one can intend other than what one desires, or judge someone else's desires to be wrong as well. An intention is a desire that has been questioned (however thoroughly) and found (however correctly) to be the correct interpretation of appetites, the correct picture to use as a guide for the world, the correct opinion with world-to-mind fit.