-

Metaphysician Undercover

14.8kThe irritation of doubt is the only immediate motive for the struggle to attain belief. It is certainly best for us that our beliefs should be such as may truly guide our actions so as to satisfy our desires; and this reflection will make us reject every belief which does not seem to have been so formed as to insure this result. But it will only do so by creating a doubt in the place of that belief. With the doubt, therefore, the struggle begins, and with the cessation of doubt it ends. Hence, the sole object of inquiry is the settlement of opinion. We may fancy that this is not enough for us, and that we seek, not merely an opinion, but a true opinion. But put this fancy to the test, and it proves groundless; for as soon as a firm belief is reached we are entirely satisfied, whether the belief be true or false. And it is clear that nothing out of the sphere of our knowledge can be our object, for nothing which does not affect the mind can be the motive for mental effort. The most that can be maintained is, that we seek for a belief that we shall think to be true. But we think each one of our beliefs to be true, and, indeed, it is mere tautology to say so. — Mapping the Medium

Metaphysician Undercover

14.8kThe irritation of doubt is the only immediate motive for the struggle to attain belief. It is certainly best for us that our beliefs should be such as may truly guide our actions so as to satisfy our desires; and this reflection will make us reject every belief which does not seem to have been so formed as to insure this result. But it will only do so by creating a doubt in the place of that belief. With the doubt, therefore, the struggle begins, and with the cessation of doubt it ends. Hence, the sole object of inquiry is the settlement of opinion. We may fancy that this is not enough for us, and that we seek, not merely an opinion, but a true opinion. But put this fancy to the test, and it proves groundless; for as soon as a firm belief is reached we are entirely satisfied, whether the belief be true or false. And it is clear that nothing out of the sphere of our knowledge can be our object, for nothing which does not affect the mind can be the motive for mental effort. The most that can be maintained is, that we seek for a belief that we shall think to be true. But we think each one of our beliefs to be true, and, indeed, it is mere tautology to say so. — Mapping the Medium

I think we need to distinguish between doubting the means, and doubting the end. Notice that this passage takes the ends (desires) for granted, so that the doubt being talked about is doubt of the means.

"It is certainly best for us that our beliefs should be such as may truly guide our actions so as to satisfy our desires;...".

When the belief 'satisfies our desire', as the means to the end, then we are not inspired to doubt the means because the result, end, is insured as that satisfaction. So long as the desire itself, the end, is never doubted, and the means are observed to be successful, then doubt is only relative to the efficiency of the means. Now means are empirically justifiable, as we demonstrate that action A produces the desired end Z. Then various ways of producing Z can be compared, A, B, C, analyzed, and the resulting "settlement", which method best produces Z, can obtain to a level higher than mere opinion.

However, such justified settlements rely on taking the end for granted. It is only relative to the assumption that the end Z is what is truly desired, that the means are in this way justified. Doubting the end itself puts us squarely into the field of opinion, unless the end itself can be justified as the means to a further end. In traditional moral philosophy there is a distinction made between the real good, and the apparent good. The apparent good is nothing but personal opinion, but the real good is assumed to somehow transcend personal opinion.

The fault in the quoted passage is the following:

" And it is clear that nothing out of the sphere of our knowledge can be our object, for nothing which does not affect the mind can be the motive for mental effort."

This statement inverts the real, or true, relation between the being with knowledge and the object of that being, which is its goal or end. Knowledge, as justified opinion, explained above, is always justified as the means to the end. But the end which justifies the knowledge is simply assumed as an opinion, and this places "our object", which is the goal that motivates us, as outside of knowledge itself, as unjustified opinion. This is what Plato demonstrated in "The Republic", "the good" must be apprehended as outside of knowledge.

So the statement incorrectly asserts that the motivating object, the end, or the good, cannot be outside "the sphere of our knowledge". A proper analysis indicates that only the means to the end can be justified as knowledge, while the object itself, the end or good, must be apprehended as outside the sphere of knowledge. Therefore moral traditionalists characterize the apparent good as opinion, and the real good as understood only by God. This places "our object" as firmly outside "the sphere of our knowledge".

Making this switch produces a completely different understanding and conceptualization of the division between active and passive elements of reality, outlined by Aristotle. Notice in the quoted statement, that the mind must be "affected" by its object, to be motivated by it. This characterizes the end, or object, as active, and affecting the mind. But when the end, or object is understood as opinion, then it is necessary to assume something within the mind which is other than knowledge. Opinion is not knowledge. Being created within the mind, by the mind, opinion is the effect of the mind, and improperly represented as affecting the mind, with "the motive for mental effort".

This reversal is what allows us to doubt the object, or end. Being created by the mind, it is within the mind, and therefore can motivate, but being unjustified leaves it outside of knowledge. Therefore it ought to be doubted. In other words, the mind creates its object, goal, end, or good, and this created object "acts" as the source of motivation for knowledge, and the means, as human actions in general. When we take the object, goal, end, or good, for granted, we represent this as the object affecting the mind to produce knowledge in the form of means. And this is what is expressed in the passage. But to properly understand, we need to doubt that which is taken for granted in this representation, the object, goal, end, or good. Therefore we ought to doubt, that which is taken for granted in this passage, the object, goal, end, or good. And this exercises the mind's true capacity to actively create the object, rather than simply allowing the object to affect the mind, by taking the obect for granted.

And when we get beyond this assumption, of taking the object for granted, we learn that the mind actually creates its own object, goal, end, or good, in a field which is other than knowledge, the field of opinion. Then the "motive for mental effort" is not something which affects the mind, but something created by the mind, and this places that object firmly within the mind, but outside of knowledge. And of course this validates, the self-evident truth that the motive for mental effort, the existence of the unknown, is outside the sphere of knowledge. -

Mapping the Medium

366I think we need to distinguish between doubting the means, and doubting the end. Notice that this passage takes the ends (desires) for granted, so that the doubt being talked about is doubt of the means. — Metaphysician Undercover

Mapping the Medium

366I think we need to distinguish between doubting the means, and doubting the end. Notice that this passage takes the ends (desires) for granted, so that the doubt being talked about is doubt of the means. — Metaphysician Undercover

No doubt. ... Thank you for bringing this up. ... I do want to point out again that to understand Peirce is to understand that he tries to walk the reader through what he suspects is their perceived 'notions' and then circles back around (there's that synechism in action) to point out aspects to reconsider. ... This is why the word 'architectonic' is so often used to describe Peirce's work. ... This was one of his first essays published in 'The Monist'. ... Again, understanding the constraints and environment of the time helps to understand why and how he formatted his essays the way that he did. ... It's important to also understand that William James was his best friend. And since Charles was ostracized from the academic community, James was helping him financially. James was a nominalist, and Peirce saw the errors in nominalism, so he walked a fine line with his essays. .... Please take Peirce as a whole, without dissecting and reducing his work and potentially misunderstanding his aims. -

Metaphysician Undercover

14.8k

Metaphysician Undercover

14.8k

I have a lot of respect for Charles Peirce, but from what I've read, he misses the mark with his ontology of "the object". This might be due to a desire to disprove nominalism, but he allows unintelligibility to be an essential aspect of "the object" and this leads to the acceptance of vagueness as an ontological principle.

He posits an unnecessary separation between sign and object. For example, the sign is the numeral 2, and the object is the number two. There is no need for "the number two", as the numeral might serve as both the sign and the object. This unnecessary separation produces an unnecessary layer between the sign and the interpretation of the sign, the unnecessary layer being "the object".

That produces an inaccessible, unknowable, relation between sign and object. Therefore both the object and the sign, lose their otherwise assumed to be necessary identity, as identity being the same as the thing itself, by the law of identity. Neither the sign has a necessary identity, nor does the object have a necessary identity, as there is merely an undefined relation between these two. The result is that the object is no longer restricted by the law of identity, because of the assumed relation between the object and the sign which is not a relation of identity, i.e. the sign is other than the object. So if the sign, and the object are both present to the mind, these two are distinct, not the same, and there can be no necessary relation between the two, unlike when the sign and the object are one and the same by an identity relation.

I believe that phenomenology, especially as developed by Derrida, provides a better ontology of objects by allowing that the sign is the object. -

Mapping the Medium

366This unnecessary separation produces an unnecessary layer between the sign and the interpretation of the sign, the unnecessary layer being "the object". — Metaphysician Undercover

Mapping the Medium

366This unnecessary separation produces an unnecessary layer between the sign and the interpretation of the sign, the unnecessary layer being "the object". — Metaphysician Undercover

Can you tell me what written work of his you are referring to?

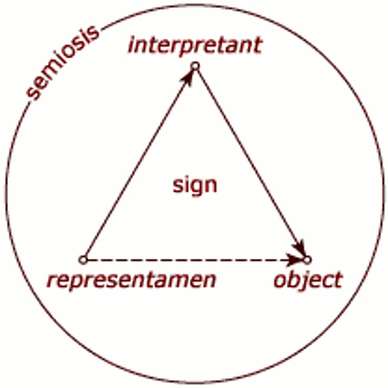

As for Peirce's 'representamen' and triadic model, we need to recognize that he is pointing to what the sign means to the interpreter. ... It does take on a different identity than just considering what some might refer to as a specific ideal form.

For instance, here is an image that can mean different things to different cultures. ...

The 'object' is exactly the same, but the 'representamen' has a different identity.

I seem to be having trouble posting an image. I put the link to the photo as requested, but it's not showing.

Perhaps this will work...

-

Mapping the Medium

366I believe that phenomenology, especially as developed by Derrida, — Metaphysician Undercover

Mapping the Medium

366I believe that phenomenology, especially as developed by Derrida, — Metaphysician Undercover

As for phenomenology, Derrida, Merleau-Ponty, etc, ... We could easily fill up another thread on what I have to say about that. :wink:

Here's a link to some notes I wrote some time back. .... Phenomenology or Phaneroscopy? -

Mapping the Medium

366I believe that phenomenology, especially as developed by Derrida, provides a better ontology of objects by allowing that the sign is the object. — Metaphysician Undercover

Mapping the Medium

366I believe that phenomenology, especially as developed by Derrida, provides a better ontology of objects by allowing that the sign is the object. — Metaphysician Undercover

Have you ever seen this video? It's been around a while, but no longer rising to the top. ... It talks about some of what you are referring to.

https://youtu.be/GITVPh7GVSE?si=5pgDM9rizZ6rAvyA

Phenomenology is definitely not my cup of tea, due to it being historically influenced by nominalism that was nurtured in the arms of religious theology. ... And Bakhtin had his own religious undertones, but as I mentioned previously, I do not see any of my favorite philosophers as being the end all be all. I have found what I think is a golden trail of breadcrumbs that travels through their combination.

If you decide to watch the video, perhaps it will provide more clues as to where (as the video puts it) I part company with phenomenology. ... There is a second part, a continuation of the video, if you should discover that it interests you. -

Metaphysician Undercover

14.8kCan you tell me what written work of his you are referring to? — Mapping the Medium

Metaphysician Undercover

14.8kCan you tell me what written work of his you are referring to? — Mapping the Medium

That "unnecessary" layer is my interpretation. As I explained, it can be understood with reference to mathematical Platonism. We understand "the number two" as the object between the numeral "2", and the interpretation performed by a person's mind. I believe this "object" is superfluous, a completely unnecessary layer added into the interpretation for various reasons within mathematical theory. In other words, it's simply part of the interpretation, serving a specific purpose, rather than a separate layer.

As for Peirce's 'representamen' and triadic model, we need to recognize that he is pointing to what the sign means to the interpreter. ... It does take on a different identity than just considering what some might refer to as a specific ideal form.

For instance, here is an image that can mean different things to different cultures. ...

The 'object' is exactly the same, but the 'representamen' has a different identity. — Mapping the Medium

This issue is, why do you, and Peirce assume "an object", which is "exactly the same"? I apprehend a sign, and I interpret the sign. The sign is interpreted by me, in a way which may be different from others. For what purpose is "an object" posited? The only answer I can find for this question, is that it provides a grounding for the claim that there is a right, or correct, interpretation.

The problems with Peirce's triadic model become evident in the work of those who have followed him, and actually employ it. The issue is 'the rules for interpretation', as indicated by Wittgenstein. The rules must comprise 'the object', in order that "the object' supports a correct interpretation. In other words, the supposed 'object' is nothing but the rules for interpretation. With Peirce's model, the rules for interpretation cannot be within the mind of the interpreter because the differences between various minds would not support the premise that "the 'object' is exactly the same". And since there is nothing between the sign and the mind which interprets, to support the independent reality of those rules, the rules must be within the sign itself. This is evident in biosemiotics.

Placing the rules for interpretation within the sign itself is very problematic because these rules would need to be interpreted. The interpretations of the rules by various minds would differ, and nothing would support the premise that "the 'object' is exactly the same", unless the sign itself, and the rules for interpretation are one and the same, as 'the object'. But then there is just the interpreter and the sign, while 'the object' is superfluous, and there is no intermediate layer.

Furthermore, placing the rules for interpretation as within the sign itself is very problematic because then it is not the mind which is doing the interpretation, having no rules for that, but the sign must be interpreting itself, and this ends up leaving the interpreting mind itself as superfluous, unnecessary. And this is exactly how biosemiotics has been mislead. The sign becomes self-interpreting and the requirement of an agent which interprets is lost, as the sign is both passively interpreted, and actively interpreting.

This all indicates that the triadic model has as a premise, an unnecessary third aspect. The superfluous aspect 'the object' may be placed as desired, depending on the application. In mathematical Platonism 'the object' is associated with the mind of the interpreter, as an independent idea grasped by that mind. In biosemiotics, 'the object' is associated with the sign, as the rules for interpretation inhering with the sign itself.

Phenomenology is definitely not my cup of tea, due to it being historically influenced by nominalism that was nurtured in the arms of religious theology. — Mapping the Medium

You seem to have a strong prejudice against nominalism. Why? -

Mapping the Medium

366You seem to have a strong prejudice against nominalism. Why? — Metaphysician Undercover

Mapping the Medium

366You seem to have a strong prejudice against nominalism. Why? — Metaphysician Undercover

In the past, I have learned to not go down the nominalism road on this forum. This time, I would like to stay a while.

I can either point you to my essays or post the very long essays in entirety here. Which would you prefer? -

Mww

5.4kWhich would you prefer? — Mapping the Medium

Mww

5.4kWhich would you prefer? — Mapping the Medium

I’m obviously not MU, but I asked first.

Nominalism. Denial of the reality of abstract objects? Or, denial of the reality of universals and/or general ideas? Something else? — Mww

Sorry, , for butting in, kinda. I recognize that you’re going deeper into the subject matter than my simple question asks. -

Mapping the Medium

366I’m obviously not MU, but I asked first. — Mww

Mapping the Medium

366I’m obviously not MU, but I asked first. — Mww

So sorry. ... I did not mean to overlook your request.

I do delve into this topic deeply in my essays. I will say that one of the reasons I started the thread about hypostatic abstraction, precisive abstraction, and proper and improper negation is to hopefully demonstrate some of what I write about.

Nominalism is deeply ingrained in Western culture (and the now-global-world in general), and it is very difficult for most to step outside of it and look at its history and influence when they are so influenced by it themselves due to 'thought as a system'. ... We are within what we are trying to examine. Nominalism tends to evoke the idea that the examination is objective. It is a case of recursive smoke and mirrors.

Again, I have written about this extensively. I don't want to spend a lot of time on it in threads here. It's just not a productive use of the forum. -

Mww

5.4kI did not mean to overlook your request. — Mapping the Medium

Mww

5.4kI did not mean to overlook your request. — Mapping the Medium

….yet it repeats itself.

Socrates would object in the most strenuous of terms. -

Mapping the Medium

366The problems with Peirce's triadic model become evident in the work of those who have followed him, and actually employ it. — Metaphysician Undercover

Mapping the Medium

366The problems with Peirce's triadic model become evident in the work of those who have followed him, and actually employ it. — Metaphysician Undercover

I also want to mention here that it is absolutely necessary to study Peirce and not "those who have followed him". It is a severe problem in the arena of Peirce studies that there are all sorts of 'gleanings' of snippets of his work to support ideas that would cause him to jump out of his grave and beat someone over the head.

I used to be on the Peirce Society Listserv, but it didn't take long for me to discover that it was basically ruled by a couple of academics who were clearly mixing up understandings of 'embodied'. Their Cartesian background was bleeding into Peirce's work. ... I explained that I could not accept that and left. They still send me Peirce Society emails and invites, and I appreciate that, but the Cartesian blood was more than I was willing to expose myself to. -

Mapping the Medium

366Socrates would object in the most strenuous of terms. — Mww

Mapping the Medium

366Socrates would object in the most strenuous of terms. — Mww

I invite Socrates to join in on my thread about hypostatic abstraction, precisive abstraction, and proper and improper negation. :sparkle: -

Mww

5.4k

Mww

5.4k

Ain’t gonna happen. He’s rather well-known for the questions he presents his dialectical companions, the lack of relevant response from one or another of them, would probably make him think twice when it comes to associating himself with philosophers in general. -

Mapping the Medium

366He’s rather well-known for the questions he presents his dialectical companions, the lack of relevant response from one or another of them, would probably make him think twice when it comes to associating himself with philosophers in general. — Mww

Mapping the Medium

366He’s rather well-known for the questions he presents his dialectical companions, the lack of relevant response from one or another of them, would probably make him think twice when it comes to associating himself with philosophers in general. — Mww

Lol ... ok :wink: -

Mww

5.4k

Mww

5.4k

….and speaking of presenting questions, something I distinctly remember doing, which at my age, is rather significant. -

Metaphysician Undercover

14.8kNominalism is deeply ingrained in Western culture (and the now-global-world in general), and it is very difficult for most to step outside of it and look at its history and influence when they are so influenced by it themselves due to 'thought as a system'. ... We are within what we are trying to examine. Nominalism tends to evoke the idea that the examination is objective. It is a case of recursive smoke and mirrors.

Metaphysician Undercover

14.8kNominalism is deeply ingrained in Western culture (and the now-global-world in general), and it is very difficult for most to step outside of it and look at its history and influence when they are so influenced by it themselves due to 'thought as a system'. ... We are within what we are trying to examine. Nominalism tends to evoke the idea that the examination is objective. It is a case of recursive smoke and mirrors.

Again, I have written about this extensively. I don't want to spend a lot of time on it in threads here. It's just not a productive use of the forum. — Mapping the Medium

As much as you think that nominalism holds sway in the western world, I find that it has been supplanted by Platonic realism, in the last few hundred years as the ontological support for materialism, "matter" being nothing but a concept. Not only that, but all forms of realism are grounded in Platonic realism. Realism is generally the default perspective, but since it requires no philosophy, many realists refuse to admit to the Platonic premises required to support their metaphysical perspective.

Since realism is what gives importance to the idea of "objects", while "object", as a concept loses importance in nominalism, it is really Platonic realism which evokes the idea that any examination is "objective". In nominalism, interpretation by the subject, is what is important, so it is inherently a subjective perspective. If nominalists claim objectivity, then they are hypocritical or self-contradicting.

I also want to mention here that it is absolutely necessary to study Peirce and not "those who have followed him". It is a severe problem in the arena of Peirce studies that there are all sorts of 'gleanings' of snippets of his work to support ideas that would cause him to jump out of his grave and beat someone over the head. — Mapping the Medium

I've read enough Peirce to see the problems I point to. As I said, I have a lot of respect for him, being very intelligent and keenly able to expose ontological problems. The issue though, is that he proposed solutions when he ought not have, because the solutions just aren't there. So his proposals aren't solutions at all, they simply mislead. In other words, his analysis is good, his synthesis is not. His proposed solutions only blur the subject/object distinction so as to veil the category mistake which the supposed solution is built on.

I can either point you to my essays or post the very long essays in entirety here. Which would you prefer? — Mapping the Medium

OK, post some links, quote some relevant passages, or just express some of what you think, whatever. Thank you. -

Mapping the Medium

366or just express some of what you think — Metaphysician Undercover

Mapping the Medium

366or just express some of what you think — Metaphysician Undercover

There's clearly no need for me to post anymore under these circumstances, but thank you. -

Metaphysician Undercover

14.8k

Metaphysician Undercover

14.8k

You're really touchy aren't you? It's as if you are actually afraid of being infected by the dreaded "nominalism thought virus".

I also want to mention here that it is absolutely necessary to study Peirce and not "those who have followed him". It is a severe problem in the arena of Peirce studies that there are all sorts of 'gleanings' of snippets of his work to support ideas that would cause him to jump out of his grave and beat someone over the head. — Mapping the Medium

Let me remind you, that when I engaged you above, I discussed explicitly the quote you brought from Peirce himself, and I addressed directly what I believed to be "The fault in the quoted passage". That fault is labeled as "taking the object for granted".

You told me, "Please take Peirce as a whole" as your way of avoiding my criticism of that passage. So when I then turned to what others say about Peirce, as a whole, you criticized me for using secondary sources.

How can I take your essays as anything other than secondary sources? And it appears like you will not discuss the problems with Peirce's philosophy with anyone other than someone who has read all of his material, and is able to take him as a whole, without referring to secondary sources. At this point you would probably just dismiss the person anyway, as having an incorrect interpretation, because you seem to think that Peirce has solved all the ontological problems of the world.

Here's a link to some notes I wrote some time back. .... Phenomenology or Phaneroscopy? — Mapping the Medium

So, I read the notes you linked to, and I'll show you how "the problem" I referred to above is revealed in that writing.

First, Peirce's term "Phaneron" characterizes a consciousness as an object instead of as an activity. It is the sum total of one's thoughts at any particular moment in time, rather than characterizing a consciousness as actively changing thoughts, all the time. So he uses that proper name "Phaneron" to name that object. So he starts from a mistaken assumption, a premise that the entirety of a consciousness can be taken as "an object". That's expressed here:

I propose to use the word Phaneron as a proper name to denote the total content of anyone consciousness (for anyone is substantially any other,) the sum of all we have in mind in any way whatever, regardless of its cognitive value.

Then, in the quote from Merleau-Ponty we can see the difference between this perspective, Peirce's which takes the object for granted, and the phenomenological perspective. Here:

Attention, then, is neither an association of ideas nor the return to itself of a thought that is already the master of its objects; rather, attention is the active constitution of a new object that develops and thematizes what was until then only offered as an indeterminate horizon.

Notice the difference. What is given is an "indeterminate horizon", and from this an "object" is constructed.

The problem which develops from Peirce's "taking the object for granted" is demonstrated later in your writing about "secondness", what is described as "bumping up against hard fact". Here we find the root of the problem, what I called Peirce's category mistake. Secondness is described as the physical constraints of the material world, such as walls and doors, yet it is also describe as "hard fact", and this refers to a description of the physical constraints, "fact" is corresponding truth about the physical world. So secondness, as the assumed "object", has dual existence which crosses a boundary of separation between the traditional categories of material and ideal. The "object" may be the physical constraint which we actually bump into, or it may be the supposed "hard fact" concerning that constraint.

The problem ought to be very evident to you now, as the ambiguous nature of "object". An "object" can be an aspect of the physical world, or it could also be an idea in a mind. "Secondness" is an attempt to make it a sort of medium between the two, but as I argue, that medium is fictitious, imaginary, created as a part of the interpretant.

Referring to the quote from Merleau-Ponty, we can see that "the object" is really a creation of the mind. Now Peirce, in his desire to take the object for granted, when it really cannot be taken for granted, because it is created within the mind, introduces ambiguity with his concept of "secondness", which allows "the object" to be conceptualized as either a mental object or a material object. It really cannot be conceived as something distinct and independent from the two, as a third category, like Peirce desires with the proposal of "secondness", because Peirce has not properly provided that category which is required to serve as that medium which he desires. He's really only provided ambiguity in "object" which allows "object" to be conceived of (constructed) as on one side or the other, of the two traditional categories, depending on one's purpose. -

Mapping the Medium

366How can I take your essays as anything other than secondary sources? — Metaphysician Undercover

Mapping the Medium

366How can I take your essays as anything other than secondary sources? — Metaphysician Undercover

I absolutely do not expect you to. That was my point. -

Mapping the Medium

366moment — Metaphysician Undercover

Mapping the Medium

366moment — Metaphysician Undercover

is the sum total of one's thoughts at any particular moment in time — Metaphysician Undercover

To understand 'moment' in mathematics and physics is to understand that time is a continuum, and a moment has no duration. Measuring something with zero duration is not feasible because all measurements inherently involve a finite interval.

Peirce understood this quite clearly. That understanding reveals itself in understanding his works as a whole.

Regarding 'Phaneron', Peirce is not naming an 'object'.

In synechistic terms, a moment is defined relationally, through interactions or changes. In phaneroscopy, moments are meaningful even if they cannot be measured. Their significance lies in their qualitative presence within the flow of experience, rather than their quantifiability. -

Mapping the Medium

366Secondness is described as the physical constraints of the material world, such as walls and doors, yet it is also describe as "hard fact", and this refers to a description of the physical constraints, "fact" is corresponding truth about the physical world. So secondness, as the assumed "object", has dual existence which crosses a boundary of separation between the traditional categories of material and ideal. The "object" may be the physical constraint which we actually bump into, or it may be the supposed "hard fact" concerning that constraint. — Metaphysician Undercover

Mapping the Medium

366Secondness is described as the physical constraints of the material world, such as walls and doors, yet it is also describe as "hard fact", and this refers to a description of the physical constraints, "fact" is corresponding truth about the physical world. So secondness, as the assumed "object", has dual existence which crosses a boundary of separation between the traditional categories of material and ideal. The "object" may be the physical constraint which we actually bump into, or it may be the supposed "hard fact" concerning that constraint. — Metaphysician Undercover

Again, Secondness is not an object, as in your interpretation. Firstness, Secondness, and Thirdness are a triadic relationship. There are no separations between them. As in the case of how we understand the hardness of a diamond, they are relational. You cannot experience Secondness without Thirdness. ... This is a good example of how nominalism makes it difficult to shift thinking paradigms. It is blinding. -

Mapping the Medium

366The problem which develops from Peirce's "taking the object for granted" — Metaphysician Undercover

Mapping the Medium

366The problem which develops from Peirce's "taking the object for granted" — Metaphysician Undercover

I want to expand on this a bit..... Again, it is important to recognize that Peirce was a teacher and lecturer. He used language as needed to help his students understand from their cultural perspective at the time. This is another reason to study his entire works rather than snippets.

“A REPRESENTAMEN is a subject of a triadic relation TO a second, called its OBJECT, FOR a third, called its INTERPRETANT, this triadic relation being such that the REPRESENTAMEN determines its interpretant to stand in the same triadic relation to the same object for some interpretant.” -CP Lowell Lectures, 1903

Peirce is not separately delineating an 'object' in the above excerpt from this lecture. It took me a LONG time to understand this, and it prompted me to want to learn more. Any nominalist reading this excerpt in isolation could easily misunderstand it. ... My point is to notice that he says "called' its object. He is not calling it "object", he is referring to what is commonly "called" 'object'.

Notice how he references TO a second and FOR a third. This is where the focus needs to be to understand this excerpt.

Peirce's Semiotic Model

Referring to the quote from Merleau-Ponty, we can see that "the object" is really a creation of the mind. — Metaphysician Undercover

As for Merleau-Ponty, he was a phenomenologist. ... I am a phaneroscopist. There is a substantial (major) difference. My exploration of Merleau-Ponty helped me to see that. That was the whole point of my written piece on the topic. -

Metaphysician Undercover

14.8kAgain, Secondness is not an object, as in your interpretation. — Mapping the Medium

Metaphysician Undercover

14.8kAgain, Secondness is not an object, as in your interpretation. — Mapping the Medium

As I said, "object" is left ambiguous by Peirce. I haven't offered any interpretation of "object" due to this problem. And you are wrong to say that secondness is not the object.

My point is to notice that he says "called' its object. He is not calling it "object", he is referring to what is commonly "called" 'object'. — Mapping the Medium

Mapping the Medium, face the reality, he is explicitly saying that it is what is commonly called "object". And he uses that term to say that it's called "its object". Why argue this. it's essential to understanding the triadic relation he proposes? Secondness is what we commonly call "object",

Now the problem is that there is ambiguity as.to what is commonly called "object". There is a physical object, and there is an object of the mind which is better known as an idea. Peirce intentionally exploits this ambiguity, because he seems to think that this will somehow solve some ontological problems.

It does not, and that is because physical "objects" have an identity according to the law of identity. Mental objects (ideas) cannot be assigned identity. So when you say "the REPRESENTAMEN determines its interpretant to stand in the same triadic relation to the same object for some interpretant", it could only be "the same object" if it was a physical object. Only physical objects have this "sameness" assignment by the law of identity. But Peirce wants this principle to apply to mental objects (ideas) as well, and this forces him to make exceptions to the law of noncontradiction, and the law of excluded middle, to account for the reality of these supposed mental objects, which are not really objects with identity, at all. -

Mapping the Medium

366he uses that term to say that it's called "its object". Why argue this — Metaphysician Undercover

Mapping the Medium

366he uses that term to say that it's called "its object". Why argue this — Metaphysician Undercover

Peirce isn’t conflating or confusing "physical objects" and "mental objects" but rather proposing a more flexible and relational understanding of "object" as it functions within a semiotic framework.

The focus of Peirce's logic is on the semiotic framework.

You are suggesting that Peirce’s approach violates the laws of noncontradiction and excluded middle, but Peirce doesn’t see these laws as universally applicable to all aspects of reality. His logic of relatives and his commitment to synechism (the doctrine of continuity) allow for a more relationally emergent view of identity and difference. For Peirce, reality is not static but dynamically unfolding, and his logic reflects this processual nature.

The "sameness" in Peirce’s framework is not about static, metaphysical identity but rather about functional continuity across interpretations. The triadic relation ensures that meaning evolves through interpretants while maintaining a thread of continuity tied to the dynamical object. He views the "object" in the triadic relation as that to which the representamen refers, not necessarily something with a rigid ontological identity.

Peirce doesn’t reduce Secondness to physical 'objects' alone. It’s about the dynamic relation of reaction or resistance between two elements, whether physical, mental, or conceptual. So yes, the "object" in the triadic relation can be either physical or ideal, depending on the context. Again, Peirce's focus is on the semiotic triadic dynamic relation. Whereas nominalism's focus is on concretization and static identity. -

Wayfarer

26.1kAgain, it is important to recognize that Peirce was a teacher and lecturer. He used language as needed to help his students understand from their cultural perspective at the time. This is another reason to study his entire works rather than snippets. — Mapping the Medium

Wayfarer

26.1kAgain, it is important to recognize that Peirce was a teacher and lecturer. He used language as needed to help his students understand from their cultural perspective at the time. This is another reason to study his entire works rather than snippets. — Mapping the Medium

It might be mentioned in passing that Peirce's academic career was pretty brief. He lectured at Johns Hopkins University from 1879 to 1884, during which time he taught logic, largely under the auspices of James Joseph Sylvester, a mathematician who supported Peirce's work. However, Peirce’s academic career was cut short when he was dismissed in 1884 due to personal controversies and his unconventional behavior, including a scandalous divorce and second marriage, which damaged his reputation in the academy. Thereafter he and wife Juliette moved to a rural property in Milford, Pennsylvania, where they lived in considerable isolation and poverty. During these years, Peirce faced periods of severe financial distress, and there is evidence that his health deteriorated due to inadequate nutrition and poor living conditions. 'Charles spent much of his last two decades unable to afford heat in winter and subsisting on old bread donated by the local baker. Unable to afford new stationery, he wrote on the verso side of old manuscripts.' (One of the reasons sorting and publishing his voluminous materials has taken more than a century thus far.) -

Mapping the Medium

366It might be mentioned in passing that Peirce's academic career was pretty brief. — Wayfarer

Mapping the Medium

366It might be mentioned in passing that Peirce's academic career was pretty brief. — Wayfarer

Thank you for adding this background to the discussion. The quote we were examining was from one of his lectures. We can only speculate as to how his work might have had more influence if his academic career has not been cut short.

I took a road trip in the Fall of 2023 to Milford, PA to visit his home. You can read about here, if you like.

My Road Trip to Arisbe -

Metaphysician Undercover

14.8k..proposing a more flexible and relational understanding of "object"... — Mapping the Medium

Metaphysician Undercover

14.8k..proposing a more flexible and relational understanding of "object"... — Mapping the Medium

I agree with this, but I prefer the term "ambiguous" over "flexible".

You are suggesting that Peirce’s approach violates the laws of noncontradiction and excluded middle, but Peirce doesn’t see these laws as universally applicable to all aspects of reality. — Mapping the Medium

That's true, these laws are not universally applicable. That's exactly what I was arguing with RusselA earlier in the thread. In the case of a thinking subject, in the process of deliberation, and decision making in general, the person has the two opposing and contradictory ideas in one's mind, at the same time. As we discussed, having opposing ideas at the same time, "I should stay", I should go" violates the law of noncontradiction. This violation is because the person has as a property of one's mind, contradictory ideas.

However, these fundamental laws of logic are intended to dictate what we can and cannot say about physical objects. A physical object has an identity, as itself, and it does not have contradictory properties. Thinking subjects though, along with all of their thoughts and ideas, are not objects. and that is why they can violate those fundamental laws with their thoughts. The conceptions we produce do not need to follow the laws which apply to physical objects. This demonstrates a very clear difference between physical objects and ideas.

Peirce, with his "semiotic framework" attempts to annihilate this difference with his "flexible" understanding of "object". But this is a recipe for problems, because it removes the boundary, the principles of distinction, which separates the aspects of reality which obey those fundamental laws and those which do not.

Instead of the simple, and very useful division between the mind which interprets, and the thing which is interpreted (be it the physical world in general, an object, or a sign), Peirce posits the object as what is represented by the sign, as in my example, the numeral 2 represents the number two. This adds an unnecessary layer, and leaves the sign itself as a distinct category, outside our capacity to understand. The sign itself is impossible to understand, because understanding consists of knowing its object. This leaves signs themselves as inherently unintelligible, because a sign would have to be represented by another sign, and another sign, in an infinite regress.

The "sameness" in Peirce’s framework is not about static, metaphysical identity but rather about functional continuity across interpretations. — Mapping the Medium

Yes, well this is the problem. An "object", as a physical object, is "the same as itself" in every aspect, that's what makes it an object, it's uniqueness. But if we look at "functional continuity across interpretations" as what defines "sameness", relying on the concept of "differences which don't make a difference", and call this the defining feature of "the object", then we have no words left to describe the reality of physical objects in their uniqueness. "Object" now has been taken to be used in referring to this new type of object, which has a compromised form of sameness. And so we must also compromise the meaning of "same" so as to exclude the relevance of differences which don't make a difference. Then "same" just means similar. Clearly this is debilitating to ontology.

He views the "object" in the triadic relation as that to which the representamen refers, not necessarily something with a rigid ontological identity. — Mapping the Medium

This is exactly the ambiguity I am talking about. A representamen could refer to a physical object, as is common in day to day speaking, or it could refer to an idea, or concept, as is common in higher education. Traditionally we'd distinguish between these two, and assign identity to physical objects, and apply the basic laws of logic in speaking about these physical objects. The other type of referent we'd understand as an idea, a concept, a subject of study, or something like that. So we'd have a clear distinction between these two.

Now Peirce allows both of the two types of referent to be classed together as "object". But since the one type, ideas and concepts, don't have a proper identity, by the law of identity, yet he wants to give them some form of identity as the object referred to, he is inclined toward a compromised meaning of "same". This is a meaning of "same" which allows for differences, and it really means similar. But "similar" will not do the task required by Peirce, to support "the object", as one rather than many.

This is not really a problem in itself, to corrupt the use of "same" this way, but it robs us of the capacity to talk about, and understand the reality of what we know as physical objects, in their uniqueness, by stealing that word "same", and giving it a different meaning. Of course, if you're a staunch idealist like Peirce seems to be, you'll deny that there is any reality to the assumption of independent physical objects, but this denies the capacity for truth, as correspondence. And so it really just produces more problems. -

Mapping the Medium

366Of course, if you're a staunch idealist like Peirce seems to be, — Metaphysician Undercover

Mapping the Medium

366Of course, if you're a staunch idealist like Peirce seems to be, — Metaphysician Undercover

No. This is where the misconception lies. Perhaps you didn't read what I posted on the other thread. I will post it here for your review.

-----

Intrinsic Properties are characteristics that an object has in itself, independently of anything else. For example, the shape of an object is an intrinsic property.

Extrinsic Properties are characteristics that depend on an object's relationship with other things. For instance, being taller than another person is an extrinsic property.

Essential Properties are attributes that an object must have to be what it is. For example, being a mammal is an essential property of a human.

Accidental Properties are attributes that an object can have but are not essential to its identity. For example, having brown hair is an accidental property of a human.

By labeling, nominalism often concretizes properties that are actually relational. Nominalism argues that properties, types, or forms only exist as names or labels and does have the effect of concretizing abstract or relational properties. When we use labels to categorize and identify properties, we often treat them as more concrete than they might actually be.

Platonism takes this same idea and applies it to universal forms (but it is the same historically influenced idea!).

In Platonism, 'Forms' are abstract, perfect, unchanging concepts or ideals that exist independently of the physical world. According to Plato, the physical world is just a shadow or imitation of this realm of Forms.

Unlike nominalism, which treats properties as mere labels, Platonism asserts that these properties have an essential, independent existence in the world of Forms, but the issues with concretized identity are the same as in nominalism.

Platonism provides a framework where properties and identities have a deeper, more substantial existence beyond the physical realm, which SEEMS to contrast sharply with the nominalist view, butthe premise is based on the same historical development of nominalistic thought. This has its origins in religious theology. As I explained before, the view was that God can only be omnipotent if able to damn an individual sinner or save an individual saint. Discrete, individual forms/objects is the foundational idea behind both nominalism and Platonism. Continuity is disrupted in both of them. -

Metaphysician Undercover

14.8kNo. This is where the misconception lies. Perhaps you didn't read what I posted on the other thread. I will post it here for your review.

Metaphysician Undercover

14.8kNo. This is where the misconception lies. Perhaps you didn't read what I posted on the other thread. I will post it here for your review.

-----

Intrinsic Properties are characteristics that an object has in itself, independently of anything else. For example, the shape of an object is an intrinsic property.

Extrinsic Properties are characteristics that depend on an object's relationship with other things. For instance, being taller than another person is an extrinsic property.

Essential Properties are attributes that an object must have to be what it is. For example, being a mammal is an essential property of a human.

Accidental Properties are attributes that an object can have but are not essential to its identity. For example, having brown hair is an accidental property of a human. — Mapping the Medium

This just demonstrates Peirce's use of "object" is not only ambiguous, but equivocal as well.

By labeling, nominalism often concretizes properties that are actually relational. Nominalism argues that properties, types, or forms only exist as names or labels and does have the effect of concretizing abstract or relational properties. When we use labels to categorize and identify properties, we often treat them as more concrete than they might actually be. — Mapping the Medium

This makes no sense to me at all. I see no logical connection between a nominalist saying that the concrete existence of any specific property is nothing more than a label to be interpreted by a mind, and your conclusion that this "concretizes properties". Clearly, the only concrete thing here is the label, and it's obvious that the label is not the meaning. Also, it's clear that when we use a relational label, like "near" for example, we are not "concretizing" this property to say that it is part of the thing referred to as "near". Even with labels like "red", the nominalist respects that this is a word to be interpreted for meaning, conceptually, and it does not refer to a concrete part of a named object. That is just naive realism which you are criticizing, and that's worlds apart from nominalism.

In Platonism, 'Forms' are abstract, perfect, unchanging concepts or ideals that exist independently of the physical world. According to Plato, the physical world is just a shadow or imitation of this realm of Forms.

Unlike nominalism, which treats properties as mere labels, Platonism asserts that these properties have an essential, independent existence in the world of Forms, but the issues with concretized identity are the same as in nominalism. — Mapping the Medium

I can't follow what you're saying here. The law of identity "concretizes" identity by placing a thing's identity within the thing itself. This means that a thing's identity is not the whatness we assign to the thing by naming its type, nor is it a collection of properties which we define, or anything like that. it is not even the name we give to the thing, as a proper noun assigned to that particular thing only. The thing's identity is the thing itself.

Platonism, as you describe it here, does not run a foul of the law of identity. However, when these "abstract, perfect, unchanging concepts or ideals that exist independently of the physical world" are given identity as objects, then this is a problem. And that is what Peirce does with his conception of "sameness" which you describe as "functional continuity across interpretations". It is this "sameness" which allows a conception to have an identity as an object. But it's a qualified "sameness", relative only to the specified function. So that sort of "sameness" exists only within the domain of a specific purpose, and is not a true identity.

Platonism provides a framework where properties and identities have a deeper, more substantial existence beyond the physical realm, which SEEMS to contrast sharply with the nominalist view, butthe premise is based on the same historical development of nominalistic thought. This has its origins in religious theology. As I explained before, the view was that God can only be omnipotent if able to damn an individual sinner or save an individual saint. Discrete, individual forms/objects is the foundational idea behind both nominalism and Platonism. Continuity is disrupted in both of them. — Mapping the Medium

I agree with most of this, and that there is really very little difference between traditional Platonism and traditional nominalism. These two are just different ways of interpreting the relationship between the physical world, and the world of ideas. The big difference is that nominalism pays respect to the role of signs and symbols, as a necessary, and essential aspect of human concepts. This perspective denies the characterization of "abstract, perfect, unchanging concepts or ideals that exist independently of the physical world". Human abstractions and conceptions are understood to rely on physical signs and symbols, this makes it impossible for them to exist independently of the physical world.

This makes the described form of nominalism and the described form of Platonism incompatible. Now Peirce wanted to pay respect to the importance of signs and symbols, in the nominalist way, but he also wanted to hang on to the benefits of Platonism (as an easy ontology) at the same time. So he proposed that triadic system which allows for that separate, independent object, as an idea or concept, along with the signs of nominalism, all together. But what this does, as I've argued, is annihilate the distinction between a physical object and a concept. And that is not a good ontology.

Welcome to The Philosophy Forum!

Get involved in philosophical discussions about knowledge, truth, language, consciousness, science, politics, religion, logic and mathematics, art, history, and lots more. No ads, no clutter, and very little agreement — just fascinating conversations.

Categories

- Guest category

- Phil. Writing Challenge - June 2025

- The Lounge

- General Philosophy

- Metaphysics & Epistemology

- Philosophy of Mind

- Ethics

- Political Philosophy

- Philosophy of Art

- Logic & Philosophy of Mathematics

- Philosophy of Religion

- Philosophy of Science

- Philosophy of Language

- Interesting Stuff

- Politics and Current Affairs

- Humanities and Social Sciences

- Science and Technology

- Non-English Discussion

- German Discussion

- Spanish Discussion

- Learning Centre

- Resources

- Books and Papers

- Reading groups

- Questions

- Guest Speakers

- David Pearce

- Massimo Pigliucci

- Debates

- Debate Proposals

- Debate Discussion

- Feedback

- Article submissions

- About TPF

- Help

More Discussions

- Other sites we like

- Social media

- Terms of Service

- Sign In

- Created with PlushForums

- © 2026 The Philosophy Forum