-

Cheshire

1.1kAre you talking about the justification for assigning necessity or possibility to a proposition? SO your hierarchy has necessary truths at the top, necessary falsehoods at the bottom, and all sorts of contingencies in between?

Cheshire

1.1kAre you talking about the justification for assigning necessity or possibility to a proposition? SO your hierarchy has necessary truths at the top, necessary falsehoods at the bottom, and all sorts of contingencies in between?

I don't see what the problem you are trying to solve is. — Banno

In my car are a lot of fluids. One of them is necessary for the car to run. I suppose it doesn't mean anyone of them is more or less a fluid. I thought I saw something. Maybe not. -

Banno

30.6k

Banno

30.6k

There can be true things we don't know. but there can't be things we know that are not true. — Banno

knowledge is a belief that cannot be false — khaled

If you had said "knowledge is a belief that is not false" we might have agreement. The difference is that one can believe one knows something, but be mistaken. -

khaled

3.5kIf you had said "knowledge is a belief that is not false" we might have agreement. The difference is that one can believe one knows something, but be mistaken. — Banno

khaled

3.5kIf you had said "knowledge is a belief that is not false" we might have agreement. The difference is that one can believe one knows something, but be mistaken. — Banno

Yes, and I'm asking what the point of this is. Instead of simply saying "I do not know whether or not X is true/false", you now made it "If I know X that means X is not false, but I do not know whether or not I know X" so in the end, you do not know whether or not X is true/false.

So why define knowledge such that you are not wrong about something that you know, but you can still be wrong about whether or not you know something? It doesn't net you any extra certainty or anything. Just seems weird to me. -

Cidat

128It's one thing for something to be true, but another to know it's true. I can believe I exist, and it may be objectively true, without actually consciously knowing it's true. I define knowledge as conscious mental awareness of truth. Objectively I may experience something, without knowing this experience is actually occurring (according to my definition). Epistemological skeptics believe humans cannot actually know anything, only believe things.

Cidat

128It's one thing for something to be true, but another to know it's true. I can believe I exist, and it may be objectively true, without actually consciously knowing it's true. I define knowledge as conscious mental awareness of truth. Objectively I may experience something, without knowing this experience is actually occurring (according to my definition). Epistemological skeptics believe humans cannot actually know anything, only believe things. -

dclements

503

dclements

503

I believe you are talking about is do people still believe in Immanuel Kant Categorical Imperative or something along those lines.For example, does anyone continuously hold an absolute truth for how to speak? Does anyone continuously hold an absolute truth for never robbing a bank? Etc. — Cidat

https://www.britannica.com/topic/categorical-imperative

It is just about a given that the answer is "yes" that many people rely on such thinking, but thinking it such ways is both highly flawed and highly problematic. In a nutshell many of the philosophers and people during the time Kant was alive thought that morality and ethics were not that complicated so they treated it with some like kid gloves when dealing with it. However the issues with ethics/morality ARE NOT simple as Kant and other like him believe them to be and in fact they are what is called a NON-TRIVIAL problem (ie. a problem so complex that is so complex that it might not be able to be solved by humans or possibly not solved at all).

The first philosophy to really grapple the problem with such think (or at least the first one I'm aware of) is Søren Kierkegaard who explained that we have to use "subjective truths" to grapple with our understanding of moral/ethical issues and not reply on what we think are objective truths since there ma not be any objective truths or at least as far that we know of. It is Kierkegaard way of thinking who has guided many of the philosophers who came after him (at least in the subject of moral/ethical issue) and he is considered by some to be the "grandfather" of post-modern philosophy, although such a title many or many not be a good thing. -

Banno

30.6kAnd...?

Banno

30.6kAnd...?

It keeps the definition of knowledge consistent with the JTB model of knowledge. — Cheshire

Indeed it does, but that's not the motive here. Rather its just the observation that saying one knows something that is false is an erroneous use of "know"; that claims such as "I know the word is flat, but it isn't true that the world is flat" are infelicitous.

We talk about stuff we know all the time, but @khaled would have us not do so, replacing knowledge with mere belief. The infelicity remains: "I believe the word is flat, but it isn't true that the world is flat". Knowledge carries more weight than mere belief. The JTB account tries to capture this by adding truth and justification, and although not entirely successful, it does highlight the advantage knowledge has over belief.

There's a reason we have the word "know" and use it sometimes rather than "belief". Mandating that we not do so decreases the power of English. -

Apollodorus

3.4kThat's why I've always been interested in the reality of intelligible objects - like numbers. — Wayfarer

Apollodorus

3.4kThat's why I've always been interested in the reality of intelligible objects - like numbers. — Wayfarer

My theory is that intelligible objects like numbers or like Plato's Ideas are too close to the subject that thinks about them to be perceived as objects.

But if we assume that Plato was committed to a reductivist approach that sought to reduce the number of fundamental principles to the absolute minimum, then he was very close to it. I think it makes sense to say that when consciousness organizes itself in order to generate cognition, it would start with the most basic universals such as number, size, shape, color, distance, etc. which it would use as building blocks of experience. -

Banno

30.6kIt's one thing for something to be true, but another to know it's true. I can believe I exist, and it may be objectively true, without actually consciously knowing it's true. I define knowledge as conscious mental awareness of truth. Objectively I may experience something, without knowing this experience is actually occurring (according to my definition). Epistemological skeptics believe humans cannot actually know anything, only believe things. — Cidat

Banno

30.6kIt's one thing for something to be true, but another to know it's true. I can believe I exist, and it may be objectively true, without actually consciously knowing it's true. I define knowledge as conscious mental awareness of truth. Objectively I may experience something, without knowing this experience is actually occurring (according to my definition). Epistemological skeptics believe humans cannot actually know anything, only believe things. — Cidat

Good to have you back in the conversation, since it is your OP.

Scepticism has a habit of capturing one's attention. Once one learns to question everything, one can feel that it is impossible to reestablish a firm footing. But there's a funny thing about doubt: one needs a basis in order to start doubting.

But consider this image:

-

Wayfarer

26.2kMy theory is that intelligible objects like numbers or like Plato's Ideas are too close to the subject that thinks about them to be perceived as objects — Apollodorus

Wayfarer

26.2kMy theory is that intelligible objects like numbers or like Plato's Ideas are too close to the subject that thinks about them to be perceived as objects — Apollodorus

'Object' is perhaps a metaphorical expression in this context, as in 'object of thought'. Read Augustine on Intelligible Objects. -

Apollodorus

3.4k

Apollodorus

3.4k

Yes. I meant that people often conceive of Plato's ideas as some kind of mental "objects" when in fact they are part of the subject. Though not the individual subject but the Cosmic Intellect or "Mind of God". -

Cheshire

1.1k

Cheshire

1.1k

It's surely informative. If I bought a book from you titled knowledge I would anticipate anything I found in it to correspond to the facts, but if you wanted to guarantee it was free from unknown errors; I wouldn't expect to pay extra. Because your definition doesn't account for them to be there, so there removal must be costless.There's a reason we have the word "know" and use it sometimes rather than "belief". Mandating that we not do so decreases the power of English. — Banno -

180 Proof

16.5kThe thing about truth is that it doesn't matter who knows it or whether or not it is known "subjectively". Reality even moreso (whether or not a specific aspect of it is subjectively encountered). "Subjectivity" is meant to be kept to oneself ... as its private contents rarely hold up to public examination (e.g. fantasy, faith, idealism, mysticism, woo-of-the-gaps, etc).

180 Proof

16.5kThe thing about truth is that it doesn't matter who knows it or whether or not it is known "subjectively". Reality even moreso (whether or not a specific aspect of it is subjectively encountered). "Subjectivity" is meant to be kept to oneself ... as its private contents rarely hold up to public examination (e.g. fantasy, faith, idealism, mysticism, woo-of-the-gaps, etc). -

Wayfarer

26.2kI meant that people often conceive of Plato's ideas as some kind of mental "objects" when in fact they are part of the subject. — Apollodorus

Wayfarer

26.2kI meant that people often conceive of Plato's ideas as some kind of mental "objects" when in fact they are part of the subject. — Apollodorus

Ideas transcend the subject-object distinction, in that they’re neither ‘in the word’ nor ‘in the mind’ but are facets of the intelligible nature of reality, structures of thought. Not private or personal thinking but the way the mind operates on a more general, inter-subjective level. -

Wayfarer

26.2kCan science answer many of the questions philosophy asks?

Wayfarer

26.2kCan science answer many of the questions philosophy asks?

No, science cannot answer any philosophical questions. The sciences are (very roughly) intellectual disciplines that pursue the discovery of empirical truths and, where possible, laws of nature in their several domains, and the construction of empirical theories that explain them.

The questions of philosophy are not empirical questions, but conceptual and axiological ones. Scientific truths are to be attained by the employment of our conceptual network, the conceptual scheme articulated in our language (including, of course, the technical language of a given science). But one should not confuse the catch with the net. — Peter Hacker

How do we know this is the case? — 180 Proof

Through reflection on the nature of knowing - which is the basic task of self-knowledge. That is where philosophy differs profoundly from science. Science always has an object in view, as the above quote says. Philosophy is much nearer to 'now, why do I think that?' It can also be very rigorous, but it's rigorous in a different and even more difficult way than science, because of the intangibility of the subject matter. -

Wayfarer

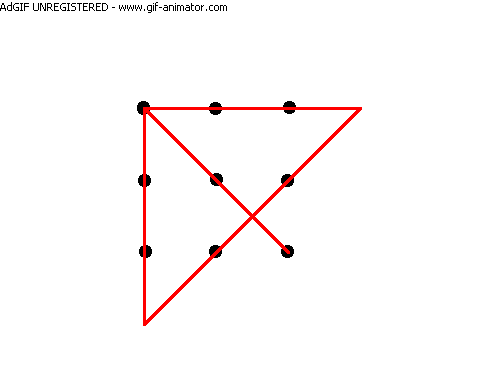

26.2kThere's that saying described as 'thinking outside the square'. The idea behind that comes from a puzzle, whereby you need to draw a straight line through a grid of dots without lifting your pencil. It turns out that the only way it can be done is by extending one of the lines beyond the grid of dots - 'outside the square'.

Wayfarer

26.2kThere's that saying described as 'thinking outside the square'. The idea behind that comes from a puzzle, whereby you need to draw a straight line through a grid of dots without lifting your pencil. It turns out that the only way it can be done is by extending one of the lines beyond the grid of dots - 'outside the square'.

By analogy, this is why we have to be willing to consider metaphysics, which are 'outside the square' of what can be objectively known.

That is in keeping with classical philosophy which always admitted ‘reasonable surmise’ as part of its reckonings. But in much of modern philosophy the naturalist attitude is taken for granted, not seeing how this limits the scope of philosophical conceivability to what is 'inside the square', what can be definitely known by means of sense and science.

Not that thinking ‘outside the square’ is venturing into completely unknown territory, it has been imaginatively mapped and charted by philosophers from many traditions. But I think we have to open to those perspectives to connect the dots, as it were.

Welcome to The Philosophy Forum!

Get involved in philosophical discussions about knowledge, truth, language, consciousness, science, politics, religion, logic and mathematics, art, history, and lots more. No ads, no clutter, and very little agreement — just fascinating conversations.

Categories

- Guest category

- Phil. Writing Challenge - June 2025

- The Lounge

- General Philosophy

- Metaphysics & Epistemology

- Philosophy of Mind

- Ethics

- Political Philosophy

- Philosophy of Art

- Logic & Philosophy of Mathematics

- Philosophy of Religion

- Philosophy of Science

- Philosophy of Language

- Interesting Stuff

- Politics and Current Affairs

- Humanities and Social Sciences

- Science and Technology

- Non-English Discussion

- German Discussion

- Spanish Discussion

- Learning Centre

- Resources

- Books and Papers

- Reading groups

- Questions

- Guest Speakers

- David Pearce

- Massimo Pigliucci

- Debates

- Debate Proposals

- Debate Discussion

- Feedback

- Article submissions

- About TPF

- Help

More Discussions

- Other sites we like

- Social media

- Terms of Service

- Sign In

- Created with PlushForums

- © 2026 The Philosophy Forum