-

Pfhorrest

4.6k"Philosophy of will" is, so far as I am aware (please correct me if I'm wrong), not generally considered a field of study unto itself, the way that philosophy of mind is, but I consider it a topic of equal importance in the overall structure of philosophical topics, so it gets its own thread in this series I'm doing.

Pfhorrest

4.6k"Philosophy of will" is, so far as I am aware (please correct me if I'm wrong), not generally considered a field of study unto itself, the way that philosophy of mind is, but I consider it a topic of equal importance in the overall structure of philosophical topics, so it gets its own thread in this series I'm doing.

Despite not being considered a field of study unto itself, there is a long history of philosophers addressing the topic of the will, especially its freedom or lack thereof. The history of that topic extends back at least as far as Aristotle, who contemplated something called the problem of future contingents, which concerns whether or not there are yet facts about future events, including about things that people will do in the future.

He and many subsequent philosophers reasoned that if there are already, in the present, facts about what will happen in the future, including the things that people will do, then that implies that those people have no choice but to do those things when those future times arrive, because it is already a fact that they will, which they held would imply that nobody ever has any freedom to choose about anything: no freedom of will. Much debate on the topic since then has hinged merely on the question of whether or not those future events are already determined, a metaphysical question, with both sides of that argument tacitly agreeing that if future events are determined, then nobody ever has any freedom of will.

But in the centuries since then many other philosophers have argued that that assumption shared between both sides of the metaphysical debate over determinism fundamentally mischaracterizes what we ordinarily mean by free will; and that not only does determinism, even if true, pose no threat to freedom of will, but indeterminism might pose an even greater threat. These philosophers have been called "compatibilists", because they hold free will to be compatible with determinism; and in contrast, those who hold them to be incompatible, whether they hold determinism to be true or not, are called "incompatibilists".

Different compatibilists have put forth different views on what is a better way to characterize free will in the sense that we ordinarily mean it, separated from this one metaphysical concern that has overshadowed the entire topic. I agree with all of them that freedom from determinism is not the important kind of freedom for freedom of will, and I consider several of the different things they put forth as better characterizations of free will to be philosophically important kinds of freedom.

But I think only one of them is the correct characterization of freedom of will in the way that we ordinarily mean it, and the importance of it is not metaphysical at all, but rather wholly ethical: what's important about freedom of will is its relationship to moral responsibility, and as I will elaborate, I hold free will to be essentially synonymous with the capacity for moral judgement, the capacity for weighing what is better or worse.

The earliest compatibilists, such as Thomas Hobbes, held that free will is simply the ability to do what one wants: regardless or whether what one will want in the future is already determined in the present, so long as one is free to do whatever that will be when the time comes, as in not physically restrained from doing so as by bars or chains, then one has free will, according to that view. Philosophers today generally consider that ability to be something separate from free will, mere freedom of action, which is not in itself of particular philosophical interest.

Other compatibilists have held that free will is instead the freedom to act without censure or punishment. But that is similarly held to be a topic not to do with the will, but rather to do with political or ethical liberty, which I will address in the next thread I have planned in this series.

Contemporary compatibilists, such as Harry Frankfurt and Susan Wolf, instead equate freedom of will with a psychological functionality, a kind of self-control or self-determination. I find that to be the most important and substantial topic regarding the will, and will address it at greater length at the end of this post.

But first I must address the metaphysical kind of freedom that is held to be of greatest concern by incompatibilists, which I will call "metaphysical will", as distinct from "psychological will". I will treat those as two separate subtopics, analogous to phenomenal consciousness and access consciousness in philosophy of mind.

As in my philosophy of mind, the philosophy of will that I am about to lay out is a hybrid of different positions, a different kind of position for each of three different senses of the word "will".

- About one sense of the word "will", the sense in which there is some special volitional causation distinct from physical causation, you could say that my position is that "nothing has free will", a position called "hard incompatibilism". To have "free will" in that sense would straightforwardly violate my physicalist ontology: whether it is deterministic or random, all causation is physical causation.

- About another sense, the sense in which there is unpredictability in the behavior of something, you could say that my position is that "everything has a free will", a position I call "pan-libertarianism".

- I think that those are both unhelpful senses of the word "will", however, and that in the ordinary sense that we normally mean the word "will", only some things have free will and others don't (just as we ordinarily think), in the manner of a position called "functionalism".

I'm going to do something I should have done in my post about philosophy of mind, where the OP was way too long, and maybe in some other threads that I split up into multiple threads, and instead split this super-long OP up into multiple posts in this one thread... -

Pfhorrest

4.6kOn Metaphysical Will

Pfhorrest

4.6kOn Metaphysical Will

Metaphysical will is largely defined by its independence from the functional process of deliberation, in much the same way that phenomenal consciousness is defined by its independence from the functionality that defined access consciousness. If we stipulate the existence of some being, like a computer artificial intelligence, that performs a deliberative process of weighing evidence and priorities and determining a course of action that is exactly like the kind of deliberative process that a human being would do, there would still be an open question as to whether such a being has metaphysical will. That is because metaphysical will is not about that function, but about the metaphysics of the causation that underlies that function.

Incompatibilists generally argue that if such a deliberative function programmed into the being behaved deterministically, always giving the same output for the same inputs, in other words always making the same decision about what the best course of action is given the same knowledge of the same circumstances and the same priorities and so on, then it would not have freedom of its metaphysical will, if it could even be said to have such a will at all.

But a counterargument, often called "The Mind Argument" for its prominence in a philosophy of mind journal called Mind, argues that if the execution of that function did not happen deterministically but instead sometimes randomly produced outputs that did not follow from the inputs, that would hardly seem to add any kind of substantial freedom to the process, because blindly following a dice roll to make a decision seems, if anything, even less free than deterministically weighing evidence and so on to make that decision. Metaphysical will is the kind of thing that is at question in these kinds of debates about determinism and randomness, regardless of what exactly the deliberative function that (deterministically, randomly, or somehow otherwise) chooses some course of action may be.

Without an answer the question of whether the universe is entirely deterministic or not, there are generally three possibilities when it comes to what kinds of beings might possibly have metaphysical will: either nothing could possibly have it, not even human beings, because the concept is simply confused nonsense; some beings, like humans, could have it, if the universe is not entirely deterministic, but not all beings would thereby have it; or if anything at all could have it, then all beings, not just humans but everything down to trees and rocks and electrons, would have it.

The first of these position, the view that nothing can possibly have metaphysical free will because the concept is confused nonsense, is called hard incompatibilism; while the latter two positions are variations of the view called metaphysical libertarianism, which so far as I know do not have well-established names for themselves, but I will dub them emergent libertarianism and pan-libertarianism for my purposes here. -

Pfhorrest

4.6kAgainst Hard Incompatibilism

Pfhorrest

4.6kAgainst Hard Incompatibilism

I am against hard incompatibilism, strictly speaking, though I am very sympathetic to the motivations for it. The incompatibilist quest for a useful notion of free will that depends on non-determinism, but is not simply randomness, does seem impossibly quixotic, because non-determinism simply is randomness. But I do not consider metaphysical will to be the useful notion of free will in the first place; that, I hold, is psychological will, which will be explored later in this post. But in answering the question of whether anything could possibly have metaphysical will or not, as useless a question as that may be to ask, I disagree with the hard incompatibilist that randomness undermines the possibility of it.

Instead, I hold, randomness is the entire essence of it: to have metaphysical will is just for the being in question to have a behavior, an output of its function, that is not entirely determined by its experience, the input of its function, and that simply is a definition of randomness. Too much randomness, or insufficient determinism, does indeed undermine the possibility of psychological will, which depends on an adequate degree of determinism to reliably maintain the functionality that constitutes it, but that is a separate question from whether anything has metaphysical will.

Against the hard incompatibilist, I hold that it is possible for things to have metaphysical will, because that would simply mean that determinism was false, which it very well could be (and according to contemporary theories of physics, it effectively is).

And if we instead slightly loosen the criterion for metaphysical free will from strict indeterminism to mere unpredictability, I hold that that is a necessary feature of any possible universe, regardless of whether determinism is strictly true or not, because predictability is self-defeating. An indeterministic universe would of course be unpredictable, but even a perfectly deterministic universe could not possibly be perfectly predictable, because the ability to perfectly predict the future is equivalent to information from the future coming to the past, and such backward transfer of information necessarily changes the future that proceeds from the moment of prediction.

In other words, predicting the future necessarily changes it, and thus renders the prediction, to some (if perhaps negligible) extent, inaccurate. These kinds of unstable feedback loops in dynamical systems, even perfectly deterministic systems, are called "chaotic", and all chaotic features render such systems inherently unpredictable, if for no other reason than the process of computing an accurate prediction in the face of such unstable complexity would necessarily take longer than the system being predicted would take to reach the future we're trying to predict.

Daniel Dennett calls this kind of unpredictability "elbow room", and holds it to provide for a kind of "compatibilist" free will that does not clash with determinism. But I hold that this sense of "free will" is still essentially the same sense as the one that incompatibilists concern themselves with – unpredictability is still not freedom of will in the ordinary, morally relevant sense, the sense that I call "psychological will" – and so is not really "compatibilist" in the same way that other forms of compatibilism are. -

Pfhorrest

4.6kAgainst Emergent Libertarianism

Pfhorrest

4.6kAgainst Emergent Libertarianism

I am also against what I dubbed above emergent libertarianism, as a part of my general position against (strong) emergentism, as already elaborated in my previous thread on the mind. I am against such emergentism on the grounds that it must draw some arbitrary line somewhere, the line between things that are held to be entirely without anything at all like metaphysical will and things that suddenly have it in full, and thus violates my previously established position against dogmatism.

Strong emergentism holds some wholes to be greater than the sums of their parts, and thus that when certain things are arranged in certain ways, new properties apply to the whole that are not mere aggregates or composites of the properties of the parts. Specifically, as regards philosophy of will, it holds that when simpler objects, that do not themselves have metaphysical free will on this account, are arranged into the right relations with each other, wholly new volitional properties apply to the composite object they create: a being with metaphysical free will is created from parts none of which had metaphysical free will.

I do agree with what I think is the intended thrust of the emergentist position, that will as we ordinarily speak of it is something that just comes about when physical things are arranged in the right way. But I think that will as we ordinarily speak of it is psychological will, to be addressed later in these posts, and that psychological will is a purely functional, deterministic property that is built up out of the ordinary deterministic behavior of the things that compose a psychologically willful being, and nothing wholly new emerges out of nothing like magic when things are just arranged in the right way.

So when it comes to metaphysical will, either it is wholly absent from the most fundamental building blocks of physical things and so is still absent from anything built out of them, including humans, or else it is present at least in humans, and so something of it must be present in the stuff out of which humans are built, and the stuff out of which that stuff is built, and so on so that at least something prototypical of metaphysical will as humans exhibit it is already present in everything, to serve as the building blocks of more advanced kinds of metaphysical will like humans exhibit. -

Pfhorrest

4.6kPan-Libertarianism

Pfhorrest

4.6kPan-Libertarianism

That latter position is what I have dubbed pan-libertarianism: the view that everything at least has something prototypical of metaphysical agency as we mean it regarding human will. That is the position that I hold: the kind of free will that incompatibilists are concerned about, that I've called "metaphysical will", is something that everything, even and especially the most fundamental particles in the universe, has. But in saying that everything has metaphysical will, I'm not really saying very much of substance.

It is merely the flip side of my panpsychist philosophy of mind, in light of the relationship between experience and behavior outlined in my earlier thread about ontology: every experience is in truth an interaction, seen equally well from a different perspective as a behavior instead of an experience.

Indeed, just as I compared that kind of panpsychist phenomenal experience to quantum-mechanical "observation" (distinguished from a more useful and robust access-conscious sense of "observation"), so too in quantum mechanics are those "observations" held to in fact be simply interactions, and it is those very interactions that introduce randomness, or at least the subjective appearance of randomness, to a quantum-mechanical model of the world (which otherwise models everything as deterministically evolving wave functions until the moment of "observation", or interaction with another system, at which point, at least from the perspective of the "observer", the wave function appears to randomly collapse into one of many possible classical states).

I hold that everything, even simple particles like electrons, has "free will", but only to the same extent that they have "consciousness": in an obscure technical sense they do, but only a pragmatically useless sense of the word that is only the topic of long-intractable philosophical quandaries.

Everything has control (and thus freedom) of some sort, in that its very existence changes the flow of events – otherwise they would not appear to exist at all, and so not be real at all on my empirical realist account of ontology – but only some things have self-control, and that is what the rest of these posts will discuss. Being able to predict what someone or something will do is not the same as them being forced to do it in any practical sense, and likewise, merely being unpredictable is not a pragmatically useful kind of freedom. -

Pfhorrest

4.6kOn Psychological Will

Pfhorrest

4.6kOn Psychological Will

The pragmatically useful sense of "free will" is, I hold, a functional one, just like the pragmatically useful sense of "consciousness". Just producing behavior that is not determined by experience is not really anything of note; it is the function that produces that behavior that may or may not be worth considering "free willed" in the ordinary sense that we use that term.

And not only is randomness or non-determinism unnecessary for such a function to constitute free will in that ordinary sense, but too much randomness, or too little determinism, would actually undermine that function, because I hold freedom of will to be essentially the ability to evaluate reasons to do one thing over another, to weigh possible intentions against each other and decide which of them is the right one to intend, and then for that evaluation to be actually effective on your behavior (as opposed to either not doing such an evaluation to begin with, or to finding yourself behaving in ways you had already decided you shouldn't, as from a compulsion or phobia). Randomness would only add errors to the evaluative process, or impede it's effectiveness upon behavior, and so only serve to undermine free will, not to enhance it.

I call this combination of pan-libertarianism about metaphysical will and functionalism about psychological will "functionalist pan-libertarianism". And like with consciousness, defining exactly what the function of a free will is in full detail is more the work of psychology (mapping the functions of naturally evolved minds) and computer science (developing functions for artificially created minds) than it is the proper domain of philosophy, but for the rest of these posts I will outline a brief sketch of the kinds of functions that I think are important to qualify something as a free will, in the ordinary sense by which we would say that humans definitely sometimes have free will, and dogs occasionally might, but a tree probably never does, and a rock definitely does not. -

Pfhorrest

4.6kOn Appetites and Desires

Pfhorrest

4.6kOn Appetites and Desires

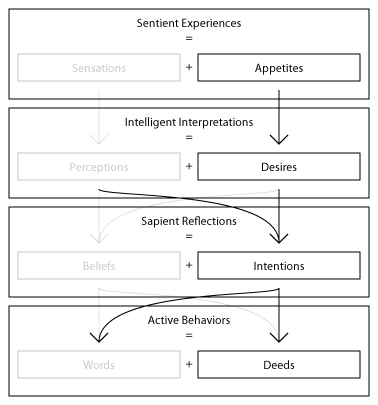

As with consciousness, the first of these important functions, which I call "sentience", is to differentiate experiences toward the construction of two separate models, one of them a model of the world as it is, and the other a model of the world as it ought to be. These differentiate aspects of an experience, which as outlined in my thread about ontology is an interaction between oneself and the world, into those that inform about about the world, including what kind of things are most suited to it, which form the sensitive aspect of the experience; and those that inform about oneself, and what kind of world would be most suited to oneself, which form is the appetitive aspect of the experience.

From these two models we then derive the output behavior from a comparison of the two, so as to attempt to make the world that is into the world that ought to be. This is in distinction from the simpler function of most primitive objects, where experiences directly provoke behaviors in a much simpler stimulus-response mechanism, and no experience is merely indicative of the nature of the world, but all are directly imperative on the next behavior of the object.

Those experiences that are channeled into the model of the world as it is I call "sensations", and I have already discussed them, their interpretations into perceptions, and the reflection upon perceptions to arrive at beliefs, in my earlier thread on the mind.

Meanwhile, those experiences that are channelled into the model of the world as it ought to be I call "appetites". Appetites are the raw, uninterpreted experiences, like the feeling of pain or thirst or hunger. When those appetites are then interpreted, patterns in them detected, identified as abstractions, that can then be related to each other symbolically, analytically, that is part of the function that I call "intelligence" (the other part of intelligence handling the equivalent process with sensation), and those interpreted, abstracted appetites output by intelligence are what I call "desires", or "emotions". -

Pfhorrest

4.6kOn Intentions

Pfhorrest

4.6kOn Intentions

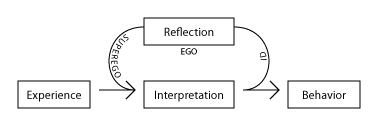

None of this is yet sufficient to call something free will in our ordinary sense of the word. For that, we need all of the above plus also another function, a reflexive function that turns that sentient intelligence back upon the being in question itself, and forms perceptions and desires about its own process of interpreting experiences, and then acts upon itself to critique and judge itself and then filter the conclusions it has come to, accepting or rejecting them as either soundly concluded or not. That reflexive function in general I call "sapience", and the aspect of it concerned with critiquing and judging and filtering desires I call "will" proper.

(I see the concepts of "id", "ego", and "superego" as put forward by Sigmund Freud arising out of this reflexive judgement as well, with the third-person view of oneself that one is casting judgement upon being the "id", the third-person view of oneself casting judgement down on one being the "superego", and the first-person view of oneself, being judged by the superego while in turn judging the id, being the "ego"; an illusory tripartite self, as though in a mental hall of mirrors).

The output of that function – an experience taken as imperative, interpreted into a desire, and accepted by sapient reflection – is what I call an "intention".

As you may recall from my earlier thread on meta-ethics and the philosophy of language, I take such intentions to be equivalent to what are sometimes called "moral beliefs", or more accurately, the normative equivalent of beliefs, prescriptive thoughts or judgements (as distinguished both from descriptive thoughts, or beliefs, and from prescriptive feelings, or desires). The forming of intentions is what I take to constitute willing, so the will (and its intentions, and their predecessors like desires and appetites) is on this account the "subject of morality" in the same way that the mind is the "subject of reality": it is the aspect of subjective experience that is concerned with morality, with what ought to be.

The will, in this more important sense of psychological will rather than metaphysical will, is not at all about causation or lack thereof, but about purpose, a prescriptive issue, not a descriptive one. And the efficacy of willing upon actual behavior is what I take to constitute freedom of the will: you have free will if the process of deliberating about what is the best course of action is effective in making you do what you decided would be the best course of action; which is about causation, yes, but only in that it depends upon it, not in that it is threatened by it.

The proper conducting of this process of willing or intention-formation is the subject of the next thread I'll do once this one dies down, which, as promised earlier, will also tackle the last of the three philosophically interesting senses of "free will" laid out near the start of this thread, the sense equivalent to liberty, as well as its inverse, duty. -

javi2541997

7.3kthe importance of it is not metaphysical at all, but rather wholly ethical: what's important about freedom of will is its relationship to moral responsibility, and as I will elaborate, I hold free will to be essentially synonymous with the capacity for moral judgement, the capacity for weighing what is better or worse. — Pfhorrest

javi2541997

7.3kthe importance of it is not metaphysical at all, but rather wholly ethical: what's important about freedom of will is its relationship to moral responsibility, and as I will elaborate, I hold free will to be essentially synonymous with the capacity for moral judgement, the capacity for weighing what is better or worse. — Pfhorrest

Despite the fact that is free interpretation of what we should consider as better or worse I think there have to be a way to reinforce it. Thus, justice or judicial power. I truly believe this is the most important tool to use in ethics. You quoted previously Thomas Hobbes and as this philosopher said: Homo homini lupus. There always been there someone who wants hurt other because they do not understand basic ethics.

So, in this way we have to improve the most representative authority about responsibility and ethichs: courts..

I have to admit that somehow law is sometimes flawed. But this is not a cause of not believing in justice because if we do not do so, everything would be a chaos and ethics could disappear.

Too much randomness, or insufficient determinism, does indeed undermine the possibility of psychological will, which depends on an adequate degree of determinism to reliably maintain the functionality that constitutes it, but that is a separate question from whether anything has metaphysical will. — Pfhorrest

Interesting explanation. This is another thought I learned today :100:

Everything has control (and thus freedom) of some sort, in that its very existence changes the flow of events – otherwise they would not appear to exist at all, and so not be real at all on my empirical realist account of ontology – but only some things have self-control, and that is what the rest of these posts will discuss. — Pfhorrest

Could be this a good argument to reinforce the judicial power/law then? -

Pfhorrest

4.6kI'm not arguing against institutes of justice, if that's what you're talking about. I'm not saying that we should just "let our free will judge what is morally good", as in "do as thou wilt shall be the whole of the law".

Pfhorrest

4.6kI'm not arguing against institutes of justice, if that's what you're talking about. I'm not saying that we should just "let our free will judge what is morally good", as in "do as thou wilt shall be the whole of the law".

What I'm suggesting in this thread is that what it means to "freely will" something is to judge that something is the correct thing to do, and then have that judgement actually guide your actions; in contrast to doing something you didn't mean to do, or something that you didn't realize was a bad thing, or something you just didn't give any thought to, or anything like that, which are all paradigmatic cases of un-free will.

People exercising their will / moral judgement are still likely to make errors in that judgement, so it's still important that other people correct them, but that's a different topic to the one that I'm talking about here, which is simply "what does it even mean to will something?" I think it means to judge something as the correct course of action. And for that will to be free is for that judgement to actually direct your action. -

javi2541997

7.3k

javi2541997

7.3k

Yes! I did understand your point but I was only suggesting that justice could be just another tool of reinforce the good ethics in free will.

My intention was not go against your topic and you are right that probably bringing here law and justice is a stupid tangent that is not connected with the main thread.

Sorry because I tried to participate here but I guess I need more knowledge in this topic. It will not happen again. -

Pfhorrest

4.6kNo worries, I'm just happy that anyone is engaging with my ideas at all! I just thought maybe I wasn't clear what those ideas were. I agree with you that we need institutes of justice, and more generally methods of justice for those institutes to exercise, and my very next thread is going to be about those methods, which is to say, how to conduct the will. :-)

Pfhorrest

4.6kNo worries, I'm just happy that anyone is engaging with my ideas at all! I just thought maybe I wasn't clear what those ideas were. I agree with you that we need institutes of justice, and more generally methods of justice for those institutes to exercise, and my very next thread is going to be about those methods, which is to say, how to conduct the will. :-) -

Huh

127I don't think you can freely will anything

Huh

127I don't think you can freely will anything

To freely will you need to not be restricted by anything. -

Pfhorrest

4.6kTo freely will you need to not be restricted by anything. — Huh

Pfhorrest

4.6kTo freely will you need to not be restricted by anything. — Huh

That would be what I called 'metaphysical will' above, and gave arguments for why that is not a useful sense of the word "will"; but also, in practice everything is at least a little bit 'unrestricted', and so in that (useless) sense everything has at least a little bit of 'free will'. -

Mww

5.4k

Mww

5.4k -

Pfhorrest

4.6kApplause for the inclusion of at least the conception of a metaphysical will. — Mww

Pfhorrest

4.6kApplause for the inclusion of at least the conception of a metaphysical will. — Mww

:up: A general tactic I like using in philosophy is recognizing positions that claim to be competing answers to the same question to instead be answers to completely different questions. I did a similar thing in my thread on philosophy of mind ("by 'mind' do you mean a mental substance, the having of first-person experiences, or a kind of functionality? I have different views on all three of those things"), the same tripartite split here, in my thread about dissolving normative ethics I take something like utilitarianism and something like Kantianism as good-ish answers to two different ethical questions... come to think of it even my core philosophical principles are all about differentiating between different senses of broad concepts like "objectivism", "subjectivism", "skepticism", and "fideism", and approving of one sense while disapproving of the other.

I don't have any objections to any of what you said, and it reminds me of a thought that I had a long time ago regarding determinism and free will: if determinism is true, it works backward just as much as it works forward: things that I do right now logically necessitate that things have happened in the past such that I end up doing the things I do right now. So, if determinism is true, then by typing this sentence I have determined that the dinosaurs went extinct -- because me typing this sentences necessitates me being here, which necessitates humans evolving, which necessitates the dinosaurs having gone extinct. But of course, in the way we usually talk about willing and choosing, it's ridiculous to say that by typing that sentence I chose for the dinosaurs to go extinct; the dinosaurs going extinct is just a necessary condition of me choosing to type that sentence. And because determinism is time-symmetric, it works the other way around too: (if determinism is true) the dinosaurs going extinct necessitates that I choose to type that sentence, but that has nothing to do with it being my free choice to type that sentence, because the usual way that we talk about "free choice" has nothing to do with the logical relations between disparate periods of time.

Or, an even simpler version of the above, relating back to the problem of future contingents: suppose metaphysical libertarianism were true. Presumably most people would still say that there are facts about things that happen in the past, right? I'm about to freely choose a word to type: freebird. Now the fact of my choosing that is in the past. There is a fact now about what I did choose in the past. Does that entail that my choice could not have been free? Ordinarily we would say no. So why does it matter if there's a fact about what I will do in the future, any more than it matters there's a fact about what I did in the past? It has no bearing on whether the thing I do is chosen freely or not. -

Janus

18k. The incompatibilist quest for a useful notion of free will that depends on non-determinism, but is not simply randomness, does seem impossibly quixotic, because non-determinism simply is randomness. — Pfhorrest

Janus

18k. The incompatibilist quest for a useful notion of free will that depends on non-determinism, but is not simply randomness, does seem impossibly quixotic, because non-determinism simply is randomness. — Pfhorrest

It's not so black and white. Antecedent events may influence events, not necessarily exhaustively determine them.

The idea of freedom is logically incompatible with the idea of rigid determinsim; 'nuff said! -

Pfhorrest

4.6kIt's not so black and white. Antecedent events may influence events, not necessarily exhaustively determine them. — Janus

Pfhorrest

4.6kIt's not so black and white. Antecedent events may influence events, not necessarily exhaustively determine them. — Janus

You can have a mix of determinism and randomness, sure, not just 100% of one or 100% of the other. But still the only thing you've changed about the fully deterministic picture is to add some randomness to it, which doesn't really seem like it makes anyone more free in the sense that matters to us, a morally relevant sense. "I only did it because prior events determined that I would" and "I only did it because as random chance would have it that's what I ended up doing" both sound just as bad, and "I only did it because it was the one out of several possibilities allowable by prior events that I randomly ended up doing" is no better. -

Pierre-Normand

2.9kOrdinarily we would say no. So why does it matter if there's a fact about what I will do in the future, any more than it matters there's a fact about what I did in the past? It has no bearing on whether the thing I do is chosen freely or not. — Pfhorrest

Pierre-Normand

2.9kOrdinarily we would say no. So why does it matter if there's a fact about what I will do in the future, any more than it matters there's a fact about what I did in the past? It has no bearing on whether the thing I do is chosen freely or not. — Pfhorrest

That's a very nice multi-part OP! I just finished reading the whole thing. I had copy-pasted all parts in a unique documents and saved it as a pdf in order to be able to highlight and annotate.

It looks like I will have many quibbles on a background of broad agreement about some of the core issues. My positive characterisation of the power of the will is quite similar to yours although I stress social aspects of the constitutive role of the 'reactive attitudes' a little more. I also deal somewhat differently with the thesis of 'leeway incompatibilism', which relates imperfectly to what you call 'metaphysical will'. I had very much enjoyed Susan Wolf's Freedom Within Reason, and read it two or three times. You seem to also have gained much from it, or, at least, to find common ground with her.

I'll be back with more comments. I just wanted to congratulate you for the very well crafted OP! -

Pfhorrest

4.6kI'll be back with more comments. I just wanted to congratulate you for the very well crafted OP! — Pierre-Normand

Pfhorrest

4.6kI'll be back with more comments. I just wanted to congratulate you for the very well crafted OP! — Pierre-Normand

Thanks a bunch! This is perhaps the most positive response I've ever received to any OP here -- it's exactly what I always want, "I like what you're trying to do and I have some ideas on how to do it better" -- so I'm looking forward to your further comments!

had very much enjoyed Susan Wolf's Freedom Within Reason, and read it two or three times. You seem to also have gained much from it, or, at least, to find common ground with her. — Pierre-Normand

To be honest, I haven't actually read Wolf herself, I've just read about her, when someone else compared the views I'd independently come up with to hers. The biggest actual influence on my views would probably be Frankfurt, but from what I understand Wolf's views are probably closer to mine than his. -

Mww

5.4kA general tactic I like using in philosophy is recognizing positions that claim to be competing answers to the same question to instead be answers to completely different questions. — Pfhorrest

Mww

5.4kA general tactic I like using in philosophy is recognizing positions that claim to be competing answers to the same question to instead be answers to completely different questions. — Pfhorrest

From a general academic point of view, perhaps, yes, but then I think merely as a matter of interest. And this is technically philosophizing, the dissemination of various theory qualifications, historically given.

—————

even my core philosophical principles are all about differentiating between different senses of broad concepts (....), approving of one sense while disapproving of the other. — Pfhorrest

This more like being used in philosophy proper. Still, given core principles, hasn’t one already approved one sense over all the others? I suppose one may exercise his core principles without the necessity of knowing what they actually are, but recognizing the validity of them from the feeling he gets in their manifestation in the world post hoc. -

Janus

18kYou can have a mix of determinism and randomness, sure, not just 100% of one or 100% of the other. But still the only thing you've changed about the fully deterministic picture is to add some randomness to it, which doesn't really seem like it makes anyone more free in the sense that matters to us, a morally relevant sense. — Pfhorrest

Janus

18kYou can have a mix of determinism and randomness, sure, not just 100% of one or 100% of the other. But still the only thing you've changed about the fully deterministic picture is to add some randomness to it, which doesn't really seem like it makes anyone more free in the sense that matters to us, a morally relevant sense. — Pfhorrest

If hard determinism were the case, then all acts and events would be predetermined, in which case it seems obvious there would be no freedom. If indeterminism were the case then all acts and events would be only probablistically deterministic, and that leaves room for freedom.

We understand natural events in terms of causation, so we shouldn't expect to be able to understand freedom in those terms, because if a free act were (exhaustively) caused by anything other than the actor it would not be free at all. Also if the nature of the actor were fully determined by anything other than the actor then the actor would not be free on that account either, but could only act as their fully determined nature caused.

Contemporary compatibilists, such as Harry Frankfurt and Susan Wolf, instead equate freedom of will with a psychological functionality, a kind of self-control or self-determination. — Pfhorrest

So, this is the problem with this kind of thinking, as I see it. If determinism were true then people would be either destined to achieve "self-control or self-determination", with those who do being able to control what they do and those who don't not being able to.

But the fact of whether control is achieved or not would be fully determined, meaning that those who lacked it cannot be blamed for doing what they do, and those who were able to exercise it could not rightly be praised. If humans are fully subject to the causation of nature then there is nothing to rationally justify the idea of moral responsibility, or praise and blame.

It would be like counting the corn as being morally responsible and praiseworthy for feeding us and sustaining life, and the lightning for being moral responsible and blameworthy for striking us dead. -

Pfhorrest

4.6khard determinism — Janus

Pfhorrest

4.6khard determinism — Janus

NB, FYI, that the term "hard determinism" refers specifically to the combination of determinism with incompatibilism. It doesn't just mean "full determinism with no indeterminism".

If hard determinism were the case, then all acts and events would be predetermined, in which case it seems obvious there would be no freedom. If indeterminism were the case then all acts and events would be only probablistically deterministic, and that leaves room for freedom. — Janus

And to the extent that determinism is not true, indeterminism is true, which then makes the argument for hard incompatibilism: one way or another free will is impossible.

The problem with that argument is that it conflates two different senses of the term "free will". Indeterminism is a threat to the usual, useful, psychological sense, because if you just do things at random, you're obviously not choosing what to do. But indeterminism is not a threat to the metaphysical sense, since that sense just is freedom from determinism, which just is indeterminism. And then we circle back around to indeterminism not being a useful kind of freedom... which just goes to show that the metaphysical sense of the term "free will" is not a useful sense of the term.

We understand natural events in terms of causation, so we shouldn't expect to be able to understand freedom in those terms, because if a free act were (exhaustively) caused by anything other than the actor it would not be free at all. Also if the nature of the actor were fully determined by anything other than the actor then the actor would not be free on that account either, but could only act as their fully determined nature caused. — Janus

Something behaving in a way independent of causal effect on it just is what "randomness" means. A person who sprung into being with a character uninfluenced by anything about the world prior to their creation and who behaved in ways uninfluenced by anything about the world prior to that behavior would be a randomly-generated person doing random things. You could imagine instead a person whose character and behaviors are somewhat influenced by the prior states of the world, but now you're just adding a little determinism to that randomness.

You can keep adding more determinism until the person's character and behaviors are completely necessitated by prior events, or take more away until they're completely random again, but where in there does some mix of determinism and randomness amount to "freedom" in any useful sense? The random person is in a sense "free" from prior influences, sure, but doing things at random is not really what we usually mean when we say that someone did something of their own free will.

But the fact of whether control is achieved or not would be fully determined, meaning that those who lacked it cannot be blamed for doing what they do, and those who were able to exercise it could not rightly be praised. If humans are fully subject to the causation of nature then there is nothing to rationally justify the idea of moral responsibility, or praise and blame. — Janus

In the way we ordinarily talk about free will and moral responsibility, we do say that someone who lacks that self-control cannot be rightly blamed or praised for their actions, precisely because they lacked that self-control. The person who was able to exercise such self-control, conversely, can be praised or blamed for their actions. It's not that self-control is supposed to be praiseworthy and lack of it is supposed to be blameworthy. It's that self-control is what makes anything either praiseworthy or blameworthy, and lack of it absolves one of any praiseworthiness or blameworthiness.

Because the function of praise and blame is to reinforce or alter people's decision-making patterns: if someone makes the right choice, we give them positive feedback to let them know to make choices like that in the future, and if someone makes the wrong choice, we give them negative feedback to let them know to not make choices like that in the future. Whereas if someone did not make any choice at all, but just ended up doing something without really intending to do it, then there's no point praising or blaming them for it, because there was no choice to be made either correctly or incorrectly.

If someone's behavior was completely undetermined, they could not engage in any kind of reflective process of evaluating their own behavior, because that process would have to depend on information about the state of the universe. So completely undetermined behavior could not be freely-willed, in the sense of warranting praise or blame. That doesn't mean that their behavior has to be completely determined in order for them to have free will in that sense, but it needs to be determined enough at least that being praised or blamed will actually influence their future decisions, and it could be fully determined without undermining that requisite functionality at all.

And sure, then it wouldn't be "metaphysically free", but we already established above that that's a useless kind of freedom. -

Janus

18kNB, FYI, that the term "hard determinism" refers specifically to the combination of determinism with incompatibilism. It doesn't just mean "full determinism with no indeterminism". — Pfhorrest

Janus

18kNB, FYI, that the term "hard determinism" refers specifically to the combination of determinism with incompatibilism. It doesn't just mean "full determinism with no indeterminism". — Pfhorrest

Maybe so in the academic sphere; I use it to denote rigid or exhaustive determinism.

And to the extent that determinism is not true, indeterminism is true, which then makes the argument for hard incompatibilism: one way or another free will is impossible. — Pfhorrest

If there is a random element in nature, which allows for an open future, it doesn't follow that our actions are random; it merely allows for real self-determination, which would be impossible if all our acts were rigidly determined by antecedent causes.

NB, we have no way of determining what is actually the case. All this talk about determinism and indeterminism is just speculation about the possibilities we can imagine. But these distinctions have a logic and the logic of determinism is incompatible with the logic of freedom. That is all you need to know to put this to rest.

In the way we ordinarily talk about free will and moral responsibility, we do say that someone who lacks that self-control cannot be rightly blamed or praised for their actions, precisely because they lacked that self-control. The person who was able to exercise such self-control, conversely, can be praised or blamed for their actions. — Pfhorrest

This is incorrect; people ordinarily do praise and blame people because they think people are responsible for their actions barring mental illness. The presumption behind ordinary talk about moral responsibility and praise and blame is based on the assumption of libertarian free will.

Compatibilism is incoherent, self-contradictory, as I see it; I have read a fair bit about compatibilism and I have yet to find a clear account of how it is possible that real freedom could be compatible with determinism. I've seen a lot of fancy verbal spin, but nothing cogent. The logic of being determined by natural forces contradicts the logic of moral freedom and responsibility, end of story. So, as I see it we are either fully determined by natural forces or we are not. and to the extent that we are not we are free. Unless you can provide a plausible argument showing why this is not so I will remain unconvinced.

If someone's behavior was completely undetermined, they could not engage in any kind of reflective process of evaluating their own behavior, because that process would have to depend on information about the state of the universe. — Pfhorrest

This seems to be another example of a black and white mode of thinking. I haven't said that anyone's behavior could be "completely undetermined" by nature, all I am saying is that if it is completely determined by nature then logically it cannot be free.That is the problem you need to address. The other issue I see for your view is that you expect that if there is free self-determination then we should be able to give a causal account of how that's possible; but this very demand is self-contradictory. -

Pfhorrest

4.6kIf there is a random element in nature, which allows for an open future, it doesn't follow that our actions are random; it merely allows for real self-determination, which would be impossible if all our acts were rigidly determined by antecedent causes. — Janus

Pfhorrest

4.6kIf there is a random element in nature, which allows for an open future, it doesn't follow that our actions are random; it merely allows for real self-determination, which would be impossible if all our acts were rigidly determined by antecedent causes. — Janus

It sounds like you are separating the human agent from nature, i.e. assuming a non-physicalist philosophy of mind. But even if that were the case, the logic of causation is still the same regardless of the ontological substrate in question: if there is a non-physical thing steering the motion of the physical body within the range allowed by an only-partially-determined physical world, we still have to ask if that non-physical thing behaves deterministically or not; and if the answer is "not", then the absence of determination is still exactly what "randomness" means, so to the extent that some non-physical agency drives our physical behavior, it's still some mix of determination and randomness, and it's still not clear what about mixing those two things produces meaningful freedom.

This is incorrect; people ordinarily do praise and blame people because they think people are responsible for their actions barring mental illness. — Janus

That's exactly what I just said. I just gave an elaboration of what it means to take responsibility for your actions: it's to reflect on the reasons to do one thing versus another thing, and based on that decide that one or the other thing is the right thing to do. If you decide correctly, you deserve praise, and if you decide incorrectly, you deserve blame. If you don't make any decision at all and something just ends up happening without any intent from you involved, then you're not responsible for what happened, and don't deserve any praise of blame.

Your actions happening in a way less dependent on the facts of the world, i.e. less deterministically, more randomly, makes you less responsible, because it reduces your ability to make any decision at all.

The presumption behind ordinary talk about moral responsibility and praise and blame is based on the assumption of libertarian free will. — Janus

It's based on the assumption of free will, certainly; but "libertarian free will" is another of those technical terms like "hard determinism", that means the combination of free will with incompatibilism. Ordinary people don't always have opinions on compatibilism vs incompatibilism, and when they do have some intuition about it, they don't all side with incompatibilism. A lot of people's intuitive opinion is something like "of course determinism is true, but of course we have free will; incompatibilism is crazy because that would mean we have no free will since determinism is obviously true". (i.e. they view it as a choice between hard determinism and compatibilism, and see metaphysical libertarianism as such nonsense it's not even a consideration). I'm not saying that as an argument for compatibilism, but just contesting your claim that ordinary people are all metaphysical libertarians.

So, as I see it we are either fully determined by natural forces or we are not. and to the extent that we are not we are free. — Janus

Sure, in the sense of "free" by which a uranium atom is "free" to decay at any time, i.e. a sense that means undetermined, or random. In that sense of "free" my view called pan-libertarianism above is that everything "has free will". That just illustrates what a useless sense of "free will" that is, though. Certainly you don't think a uranium atom is morally responsible for its decay, just because its decay was not determined? Assuming you agree it's not, that then leaves us with the question of what does make one morally responsible, that a uranium atom lacks? And I gave an account of that across several posts above. -

Pierre-Normand

2.9kIt sounds like you are separating the human agent from nature, i.e. assuming a non-physicalist philosophy of mind. — Pfhorrest

Pierre-Normand

2.9kIt sounds like you are separating the human agent from nature, i.e. assuming a non-physicalist philosophy of mind. — Pfhorrest

Indeed. It seems like this is what tends to happen when libertarians hold that the 'circumstances' in which an agent acts must be taken to include the immediate 'past' of the agent herself, including the state of her own body and of her cognitive apparatus (brain, habits, character, etc.). In that case, libertarians who insist on an indeterminist requirement, treat this requirement as the provision of alternative physical possibilities when the universe has been 'rolled back', as it were, in the same exact state just before the agent deliberated or acted. While this libertarian requirement brings along troublesome consequences about luck and the intelligibility of actions that are now severed from their intelligible cognitive sources, it's not so much indeterminism that is at fault, on my view(*), but rather the disembodied conception of agency that is carried into the picture by a flawed conception of the 'circumstances' of human actions. Someone's character, just before she acts, isn't an external constraint on what she can do. It's rather part of what she is at that time, and what her intentional action will therefore reveal her to have been.

(*) ...although your point about too much indeterminism actually undermining free agency is well taken. -

Pfhorrest

4.6kSomeone's character, just before she acts, isn't an external constraint on what she can do. It's rather part of what she is at that time, and what her intentional action will therefore reveal her to have been. — Pierre-Normand

Pfhorrest

4.6kSomeone's character, just before she acts, isn't an external constraint on what she can do. It's rather part of what she is at that time, and what her intentional action will therefore reveal her to have been. — Pierre-Normand

:up: :100: -

Janus

18kYour actions happening in a way less dependent on the facts of the world, i.e. less deterministically, more randomly, makes you less responsible, because it reduces your ability to make any decision at all. — Pfhorrest

Janus

18kYour actions happening in a way less dependent on the facts of the world, i.e. less deterministically, more randomly, makes you less responsible, because it reduces your ability to make any decision at all. — Pfhorrest

I think you have it utterly arse about, but I have no further interest in discussing it with you, since all I get is the same misunderstandings of what I'm saying and the same unjustified assertions over and over, so I think I'll leave you to it.. -

Janus

18ktreat this requirement as the provision of alternative physical possibilities when the universe has been 'rolled back', as it were, in the same exact state just before the agent deliberated or acted. — Pierre-Normand

Janus

18ktreat this requirement as the provision of alternative physical possibilities when the universe has been 'rolled back', as it were, in the same exact state just before the agent deliberated or acted. — Pierre-Normand

What you seem to be missing is the realization that the idea that human decision making is determined by natural forces is a groundless assumption. How would you ever set about testing it?

Welcome to The Philosophy Forum!

Get involved in philosophical discussions about knowledge, truth, language, consciousness, science, politics, religion, logic and mathematics, art, history, and lots more. No ads, no clutter, and very little agreement — just fascinating conversations.

Categories

- Guest category

- Phil. Writing Challenge - June 2025

- The Lounge

- General Philosophy

- Metaphysics & Epistemology

- Philosophy of Mind

- Ethics

- Political Philosophy

- Philosophy of Art

- Logic & Philosophy of Mathematics

- Philosophy of Religion

- Philosophy of Science

- Philosophy of Language

- Interesting Stuff

- Politics and Current Affairs

- Humanities and Social Sciences

- Science and Technology

- Non-English Discussion

- German Discussion

- Spanish Discussion

- Learning Centre

- Resources

- Books and Papers

- Reading groups

- Questions

- Guest Speakers

- David Pearce

- Massimo Pigliucci

- Debates

- Debate Proposals

- Debate Discussion

- Feedback

- Article submissions

- About TPF

- Help

More Discussions

- A diary entry of mine regarding free will, determinism and its implication for morality

- Reasoning badly about free will and moral responsibility

- The Free Will prob:Distinguishing the relevance of the quest'n of moral over that of amoral autonomy

- The Importance of Divine Hiddenness for Human Free Will and Moral Growth

- Other sites we like

- Social media

- Terms of Service

- Sign In

- Created with PlushForums

- © 2026 The Philosophy Forum