-

Pfhorrest

4.6kSpeaking of circling back......hope you don’t mind. — Mww

Pfhorrest

4.6kSpeaking of circling back......hope you don’t mind. — Mww

Nope, glad to be talking about things other than just emergence!

Does your statement “indeterminism is no threat to the metaphysical sense” meant to indicate a metaphysical sense of free will? In which case, the statement then becomes.....indeterminism is no threat to the metaphysical sense of free will. — Mww

Yes.

If so, does it follow that indeterminism is no threat to the metaphysical sense of free will because (or, iff) the will is taken to be free to make determinations of its own kind, by its own right, in a metaphysical sense? — Mww

It's not clear to me what "make determinations of its own kind, by its own right" means, other than that the being in question causes or necessitates things to happen, but is not itself caused or necessitated to do so; i.e. it has an output that does not depend on its input.

If that's all you mean, then yes, but NB that that is just the same thing as indeterminism, which is the same thing as randomness. So indeterminism (or randomness) is not a threat to "free will" in the metaphysical sense of the term, because the metaphysical sense of the term just means "indeterminism (or randomness)".

But it doesn’t follow from that, that your “that sense just is freedom from determinism”, which if indeterminism is no threat because determinism is the case, contradicts itself. Indeterminism is freedom from determinism, but the metaphysical sense of free will makes determinism necessary, so indeterminism IS a threat to the metaphysical sense of free will. — Mww

I'm having trouble understanding this bit here, so I'll just try to clarify what I was saying before, in case that answers anything:

The metaphysical sense of free will doesn't make determinism necessary. (The psychological sense requires "determinism enough", but that's a completely different thing).

The metaphysical sense of free will just is being undetermined.

Therefore indeterminism is not a threat to free will in the metaphysical sense. (It would be a threat to it in the psychological sense, but that's a completely different thing).

Ok, so.....indeterminism is no threat because....or, iff....the will is free as a determining functionality. How, then, does it follow that the metaphysical sense of free will is not a useful sense of the term? How is it that the metaphysical sense is not the only possible sense of free will there can be, without getting involved in that damnable “....wretched subterfuge of petty word-jugglery...” (CpR, B1,C3, Para 45, 1788)? — Mww

Having trouble understanding that first sentence there still, so I'll just try to clarify my position with regards to the rest of it again.

There are several different things that we might want to talk about regarding a person's decisions and behavior:

- Did they do the behavior that they wanted to do under their own motor power, and not because something physically pushed them to do something or physically restrained them from doing otherwise?

- Did they do the behavior they wanted to do without being threatened or otherwise coerced into doing it?

- Did they do it because they thought about what the best thing to do was and decided that that was it, rather than doing something they they thought was the wrong thing to do but they just felt like they couldn't help themselves? (Like an addiction, compulsion, phobia, etc).

- Did they do something that was not necessitated by prior states of the universe?

A "yes" answer to any of these questions is something that someone has called "free will" at some point or another.

The first one is today generally called "freedom of action" instead, but some people like Hobbes said that that's all it takes to have "free will".

The second one is today generally called "political liberty" instead, but is also sometimes called "free will", at least in a casual sense.

The third one is what I'm calling the "psychological sense" of free will, and is what contemporary compatibilists like Frankfurt and Wolf mean.

The fourth one is what I'm calling the "metaphysical sense" of free will.

I say that the fourth one is not useful because all kinds of things "have free will" in that sense, but we wouldn't normally care to talk about whether or not those things have free will; I gave the example of radioactive decay, which is not determined, and therefore is "freely willed" in this sense, but nobody cares whether or not a uranium atom "has free will".

The third one is useful, because that's the kind of thing that determines whether it makes any practical sense to praise or blame, reward or punish, someone for their actions, i.e. it's the kind of thing that makes them morally responsible. If someone already agrees that what they did was bad, and regrets doing it, but felt like they just couldn't help themselves, telling them that they're bad for doing it or making them suffer to drive home that point is useless; they already agree! They intended to do otherwise but that intent was not effective in making them do otherwise; therefore, their will was not free.

The second and first ones are also useful things to care about, but they're different kinds of freedom with their own names, and so don't have to be addressed until the topic of "free will" specifically.

Isn’t there a need to distinguish kinds of determinism? If physical determinism is not true with respect to the metaphysical sense of free will, I don’t agree indeterminism is therefore true, under the same conditions. Given the metaphysical sense of free will, it is logically consistent that the sense of determinism should itself be metaphysical, in which case, determinism must be true if it be the case that the metaphysical sense of free will abides exclusively in its law-giving functionality. I don’t think it is reasonable to suppose that because a metaphysical sense of determinism is not susceptible to inductive support in the same way as physical determinism, that the conception is therefore inherently flawed. — Mww

I'm not clear what you mean here, but it sounds like you're talking about determinism in the physical world versus determinism in some kind of non-physical world that interacts with the physical world. I deny that any such non-physical world could possibly exist in the first place, but even if it did, that wouldn't solve any problems with regard to free will.

The non-physical agent would still either make the decisions it makes on the basis of prior facts (about some combination of the physical and non-physical world), in which case its decisions are determined by those facts; or else it makes its decisions without regard to the facts, at random, in which case its decisions are undetermined. There's no clear reason why we would want our decisions to be random, or any way that that makes us "free" in any useful sense, even though it's freedom from determinism.

On the other hand, the kind of process by which the facts of the world are considered and factored into the decisions that get made and the actions that get performed can be a useful kind of freedom, a freedom to do what you think you should do (and an ability to correctly assess what you should do), instead of doing things regardless of whether or not you think you should.

Correct, like all philosophy, like all art and all science... Like cars or computers, or zillions of other things. — Olivier5

Cars and computers and other physical objects that we make are made out of the stuff of the universe, and so follow whatever rules the stuff of the universe follows. They can only be strongly emergent if the universe already has such strong emergence in it: we can't just decide that e.g. if we arrange some bits of metal in a certain way it creates new energy that wasn't present in the bits of metal. We'd have to discover that the universe already had that strongly emergent feature to it, and then take advantage of that.

But we can write stories, come up with rules of games, etc, for imaginary things that exist only inasmuch as we pretend that they do, and stipulate that there's strongly emergent things in those imaginary worlds. We can stipulate that in some game, if you get five separate points all at once that batch of points gets doubled to ten points, whereas five separate points gained one at a time don't double like that. That would be a strongly emergent feature of the game world, but that wouldn't prove anything about reality, any more than writing a story about a unicorn proves that unicorns exist in reality. -

Olivier5

6.2kWe'd have to discover that the universe already had that strongly emergent feature to it, and then take advantage of that. — Pfhorrest

Olivier5

6.2kWe'd have to discover that the universe already had that strongly emergent feature to it, and then take advantage of that. — Pfhorrest

Okay so for you, all possibilities must have emerged at once, at time zero in the history of the universe, like in the mind of God. In my version, things and possibilities emerge more progressively. Emergence is spread over time and not finished or predetermined at time zero. -

Pfhorrest

4.6kThe way you've phrased that makes no sense in the most straightforward way I'd interpret it, so I can only assume you must mean something other than what it sounds like you mean.

Pfhorrest

4.6kThe way you've phrased that makes no sense in the most straightforward way I'd interpret it, so I can only assume you must mean something other than what it sounds like you mean.

Because it sounds like you mean e.g. if a bunch of atoms were to have been arranged together into the shape of a human so-and-so many billion years ago, they would not have had supposedly "emergent" features of humans like consciousness, willpower, and (to use your own example) reproduction, because the possibility of those features emerging didn't exist yet.

Or, in the case of cars and computers as you mentioned, that cars or computers at one point in the past weren't a possibility -- that arranging the same parts in the same way would not have resulted in machines that function as our cars and computers do -- but nowadays it does, because that is a possibility of emergence that has since emerged.

Or that, although right now it's not the case that if you arrange seven palladium hexagons of exactly the right proportions in the right way it will create a perpetual motion machine that outputs more energy than any of its components have, in the future that might become the case!

And of course that's all nonsense, so you must mean something else, which once again makes me think that you're taking word to mean something different than I am, and think that I mean something I don't too. -

Olivier5

6.2kI agree that the possibility was always "there" for everything, somehow, but possibilities do not actually exist ontologically. It's not like the ancient Egyptians had a thing in hand which they could call "the possibility of a steam engine". Instead, we present day folks, who know now what a steam engine is, can imagine that "it would have been possible to make one at the time of the pharaohs". But that is anachronistic. In reality, the steam engine was invented ("emerged") much later. And if the pharaohs had invented it, well, it would have emerged sooner, that's all.

Olivier5

6.2kI agree that the possibility was always "there" for everything, somehow, but possibilities do not actually exist ontologically. It's not like the ancient Egyptians had a thing in hand which they could call "the possibility of a steam engine". Instead, we present day folks, who know now what a steam engine is, can imagine that "it would have been possible to make one at the time of the pharaohs". But that is anachronistic. In reality, the steam engine was invented ("emerged") much later. And if the pharaohs had invented it, well, it would have emerged sooner, that's all. -

Pfhorrest

4.6kOkay, I figured that's probably the more sensible thing you meant, but also, that has nothing whatsoever to do with the kind of "emergence" that I've ever been talking about.

Pfhorrest

4.6kOkay, I figured that's probably the more sensible thing you meant, but also, that has nothing whatsoever to do with the kind of "emergence" that I've ever been talking about.

It was always possible to arrange bits of metal etc together into a steam engine, even if nobody did it until relatively recently. Someone starting to do something that was always possible to do isn't "emergence" in any philosophical sense, but of course I don't deny that that happens.

If you arrange the right bits of metal together in the right way, they can do something that none of the bits of metal etc alone did (like make a train move), but that thing they do all together is a combination of a bunch of things they could all already do. Compare: one person alone can't spin a car around from the outside, but a dozen people positioned in the right way each pushing in the right directions can; yet all you've done there is combine the abilities of the individual people in the right way. That's "weak emergence", and I have no objection to it, and never have, and have been explicit about that this whole time.

But some people say that if a bunch of atoms form into molecules that form into cells that form into a human being, that human being starts doing something that's not something any combination of things that cells / molecules / atoms / etc could already do, but something else entirely on top of that physical functionality. That's "strong emergence", and that's the only thing I've been arguing against with you.

So if that last thing is not the thing that you mean, then we have no fight! And I've been saying that all along, and I don't know why you keep acting like I'm arguing against against the second thing, or now the first thing. -

Olivier5

6.2kIt was always possible to arrange bits of metal etc together into a steam engine, even if nobody did it until relatively recently. — Pfhorrest

Olivier5

6.2kIt was always possible to arrange bits of metal etc together into a steam engine, even if nobody did it until relatively recently. — Pfhorrest

Physically, maybe, assuming that the laws of thermodynamics haven't changed since the bronze age. But historically, no, because you need a certain grade or quality of steel to build a steam engine, which ancient Egyptians did not have the technology for. -

Mww

5.4kIsn’t there a need to distinguish kinds of determinism?

Mww

5.4kIsn’t there a need to distinguish kinds of determinism?

— Mww

I'm not clear what you mean here, but it sounds like you're talking about determinism in the physical world versus determinism in some kind of non-physical world that interacts with the physical world. I deny that any such non-physical world could possibly exist in the first place, but even if it did, that wouldn't solve any problems with regard to free will. — Pfhorrest

I’ve not read where you deny the metaphysical domain of human reason, so I wonder how you can categorically deny the possibility of some kind of non-physical world here. If it is impossible to deny the appearance.....the seemingness......of human rationality, isn’t it permissible to grant the validity of its sufficiently critiqued cognitive machinations? Why can’t the metaphysical domain be a valid placeholder for a non-physical world?

I submit that a metaphysical domain does solve the problems of free will, if one is satisfied by mere acceptance of possible logical consistency, rather than necessary empirical proofs.

—————-

The non-physical agent would still either make the decisions it makes on the basis of prior facts (....), or else it makes its decisions without regard to the facts, at random, in which case its decisions are undetermined. — Pfhorrest

What of the possibility that determinations can be made without regard to facts, but with regard for law? In such case, those determinations cannot be in any way random.

I think we must account for A.)....circumstances in which the facts are not known, yet in which some determination is nonetheless required, and B.)....circumstances in which the facts are known but the agent makes his determinations in direct opposition to them. In other words, it doesn’t hold that the predicates of a purely physical world can be the sole arbiter of the human decision-making procedure. Which you apparently condone, given your “.....an ability to correctly assess what you should do...”, which presupposes some ability to relate a subjective judgement to its objective manifestation.

As I said.....applause for the conception of a metaphysical will, but I regret to see you spoil it by denying its usefulness. -

Olivier5

6.2kThat's "strong emergence", and that's the only thing I've been arguing against with you. — Pfhorrest

Olivier5

6.2kThat's "strong emergence", and that's the only thing I've been arguing against with you. — Pfhorrest

I hear you saying: only the things that can happen do in fact happen. Which I agree with, obviously. If they happen, they can happen.

What I am saying is: sometimes things happen for the first time, or for the first time somewhere. Say, abiogenesis happens on earth circa 4 billion years ago. Or a community of primates invents articulated language circa 50,000 years ago. Or a new book is written by a guy called Galileo. Or the steam engine is invented in Europe during the 18/19th century. And sometimes, as in these examples, this new thing works; in ways that old things did not. Truly new developments, behaviors and laws regarding them can emerge. Of course, these new behaviors and the laws regarding them are not impossible, they can emerge, after all they DO emerge. And thus they do not contradict previous laws. They just ADD something new to them.

Something like life. Or language. Or modern science. Or the industrial revolution.

That is emergence, properly conceived. It looks magic but it's not. It just happens when wholes are more than the algebraic sum of their parts. When structures matter more than their replaceable elements. -

Pfhorrest

4.6kIn short: Moral egoism; moral narcissism. — baker

Pfhorrest

4.6kIn short: Moral egoism; moral narcissism. — baker

Great reading comprehension there. :smirk:

(Hint: X as Y isn’t Y as X).

I’ve not read where you deny the metaphysical domain of human reason — Mww

I don't at all deny human reason, only that it depends at all on some kind of non-physical stuff.

so I wonder how you can categorically deny the possibility of some kind of non-physical world here — Mww

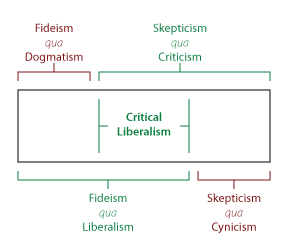

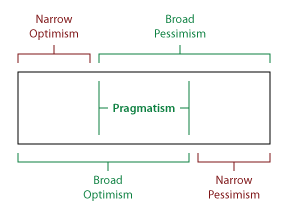

In the OP I linked to an earlier thread on my physicalist ontology. Short version is: physicalism is just empirical realism, and non-empiricism leaves no recourse except to dogmatism, while non-realism leaves no recourse except to relativism, and both dogmatism and relativism are just alternate ways of giving up on even trying to figure out what is real, so pragmatically must be rejected, which in turn (following the chain of inferences back up) necessitates empirical realism, i.e. physicalism.

What of the possibility that determinations can be made without regard to facts, but with regard for law? In such case, those determinations cannot be in any way random. — Mww

Sure, but then they would still be deterministic, and in an even less free way if what you mean by "law" is something that completely disregards the facts, i.e. if an agent will always do X regardless of circumstances, even if the circumstances would suggest he ought to do otherwise.

And thus they do not contradict previous laws. They just ADD something new to them. — Olivier5

None of the examples you gave add new laws; they are just inevitable consequences of the laws that already existed. Like I said already, if you model a whole lot of molecules just as molecules, without programming any concept of thermodynamics into your model, your model will automatically exhibit thermodynamic properties; you don't have to add anything to it. Thermodynamic properties are just shorthand for aggregates of more fundamental properties, and while it can be handy to use that shorthand when those aggregates are what you care about, you don't strictly have to; the more fundamental properties are enough, and you get the aggregate properties for free from them, without adding anything more.

When it makes sense to use such shorthand, that is emergent behavior in the "weak" sense of the term, and not anything I've ever argued against. (NB that the examples you gave above aren't even emergent in this sense; there's nothing emergent about them at all, in the way that word is usually used). It's only when you have to explicitly add new laws to account for the higher-level behavior -- like if a bunch of molecules modeled as such would not exhibit temperature unless you added a temperature parameter to the model -- that it's emergence in the "strong" sense, that I'm against.

That is emergence, properly conceived. — Olivier5

That's how you conceive it, but it's not how anyone in the philosophical literature conceives of it. -

Olivier5

6.2kNone of the examples you gave add new laws; they are just inevitable consequences of the laws that already existed. — Pfhorrest

Olivier5

6.2kNone of the examples you gave add new laws; they are just inevitable consequences of the laws that already existed. — Pfhorrest

That is simply not true. Life created new laws, like the laws of genetics.

That's how you conceive it, but it's not how anyone in the philosophical literature conceives of it. — Pfhorrest

It's how it is conceived by biologists. -

Pfhorrest

4.6kThat is simply not true. Life created new laws, like the laws of genetics. — Olivier5

Pfhorrest

4.6kThat is simply not true. Life created new laws, like the laws of genetics. — Olivier5

So you're saying that you think genetics is not just an inevitable consequence of molecules doing what molecules do, when the right molecules come together the right way, but in addition to the laws that govern those molecules, the universe has entirely separate "laws of genetics" that it invokes when molecules get together like that?

I.e. that if you build a simulation of a simple living organism, it would not be enough to simulate the laws that govern the molecules that organism is built of, but you would also have to simulate a completely separate genetic function to make the organism behave like a real organism does?

It's how it is conceived by biologists. — Olivier5

Citation needed. -

Olivier5

6.2kgenetics is not just an inevitable consequence of molecules doing what molecules do, when the right molecules come together the right way, but in addition to the laws that govern those molecules, the universe has entirely separate "laws of genetics" that it invokes when molecules get together like that? — Pfhorrest

Olivier5

6.2kgenetics is not just an inevitable consequence of molecules doing what molecules do, when the right molecules come together the right way, but in addition to the laws that govern those molecules, the universe has entirely separate "laws of genetics" that it invokes when molecules get together like that? — Pfhorrest

Whether natural laws exist or not by themselves is a matter of dispute. But it cannot be disputed that human beings have identified regularities in the working of nature, which they call laws. Some of these laws pertain to how genetics work. Get used to it.

These, by the way, are most probably NOT inevitable. Other rules could work just as well. You could replace the bases serving as letters in DNA by other bases for instance. The genetic code is arbitrary, just like any code.

Citation needed. — Pfhorrest

The concepts of systems and the possibility of their emergence are all over biology. They are the dominant paradigm since the mid-20th century. You cannot learn biology today without dabbing into system theory. One example among millions:

https://journals.physiology.org/doi/full/10.1152/japplphysiol.00942.2007

If you want to get more familiar with these ideas, I recommend François Jacob (The Logic of Life; The possible and the actual). Gregory Bateson is also very good. -

Pfhorrest

4.6kWhether natural laws exist or not by themselves is a matter of dispute. But it cannot be disputed that human beings have identified regularities in the working of nature, which they call laws. Some of these laws pertain to how genetics work. Get used to it. — Olivier5

Pfhorrest

4.6kWhether natural laws exist or not by themselves is a matter of dispute. But it cannot be disputed that human beings have identified regularities in the working of nature, which they call laws. Some of these laws pertain to how genetics work. Get used to it. — Olivier5

That doesn't answer the question at all.

Of course we've identified laws of genetics. The question is: if we perfectly modeled the molecules that, when put together the right way in real life, obey those laws of genetics, and didn't explicitly program our model with those laws of genetics, just the laws of chemistry (etc), would we just see the complex systems of molecules obeying the laws of genetics in our model automatically, even though we didn't tell the model anything about genetics?

If yes, that's only weak emergence and I've never argued against it.

If no -- if we'd have to program the model with those laws of genetics in addition to the laws of chemistry (etc) in order to see the same behavior in the complex system of molecules that we see in real life -- then that's strong emergence and that's the only thing I'm against.

These, by the way, are most probably NOT inevitable. Other rules could work just as well. You could replace the bases serving as letters in DNA by other bases for instance. The genetic code is arbitrary, just like any code. — Olivier5

You're understanding "inevitable" backward. I don't mean "is it inevitable that life would evolve to use DNA as we know it as its genetic code", but "if you simulated just the molecules of life as we know them, like DNA, in the right arrangement, would that automatically simulate life as we know it, whether we were trying to simulate life or not, because the laws governing those molecules entail the laws governing life without any additional input about the laws of life specifically?"

The concepts of systems and the possibility of their emergence are all over biology. — Olivier5

That's not the question. The question is whether the sense of emergence that you insist is the "proper" one, a sense that just means "new things happen that didn't happen before" and not any of the philosophically specific things I'm talking about above, is what biologists all mean when they say that word. -

Olivier5

6.2kRead the link.Of course we've identified laws of genetics — Pfhorrest

Olivier5

6.2kRead the link.Of course we've identified laws of genetics — Pfhorrest

Okay then.

if we'd have to program the model with those laws of genetics in addition to the laws of chemistry (etc) in order to see the same behavior on the complex system of molecules that we see in real life -- then that's strong emergence and that's the only thing I'm against. — Pfhorrest

That is I suppose the crux of your argument. Factually speaking, it is NOT TRUE that we can model, derive or compute the laws of genetics from the laws of chemistry. It hasn't been done yet. Likewise, we cannot really derive the laws of chemistry from those of QM. -

Mww

5.4kI don't at all deny human reason, only that it depends at all on some kind of non-physical stuff. — Pfhorrest

Mww

5.4kI don't at all deny human reason, only that it depends at all on some kind of non-physical stuff. — Pfhorrest

Agreed....reason cannot depend on non-physical stuff, in the strictest sense. So you.....and everybody else that “...rises to the level of speculation....” grants the necessity of physical ground for reason, but nobody knows how one follows from the other. So we don’t deny the reality of that which we know nothing real about. An insurmountable paradox best left alone.

I don’t see why we can’t say reason depends on non-physical stuff, if only because reason is itself non-physical, FAPP, and it is reason that tells us about itself. It’s how humans operate, so to reject that operational character is to reject our own intrinsic humanity.

You do decent philosophy, but at what cost? -

Pfhorrest

4.6kThat is I suppose the crux of your argument. Factually speaking, it is NOT TRUE that we can model, derive or compute the laws of genetics from the laws of chemistry. It hasn't been done yet. Likewise, we cannot really derive the laws of chemistry from those of QM. — Olivier5

Pfhorrest

4.6kThat is I suppose the crux of your argument. Factually speaking, it is NOT TRUE that we can model, derive or compute the laws of genetics from the laws of chemistry. It hasn't been done yet. Likewise, we cannot really derive the laws of chemistry from those of QM. — Olivier5

"We have not done it" is not the same as "it cannot be done".

Of course in that case we're still not certain as empirical facts can be that it can be done, which is why this is a philosophical issue rather than a scientific one. The question at hand is whether (it is reasonable) to expect that it can eventually be done, or instead that it is just in principle not possible.

That's the repeated theme throughout a bunch of my philosophy: "we haven't done it yet, but should we conclude on that basis that it therefore can't, or instead assume that it can and just keep trying to?" My answer is always the latter.

This is actually a much clearer way of formulating my objection to strong emergentism, so this has turned out to be a productive conversation after all; I'll make a note to myself to phrase it this way in the future.

In any case, I would be interested to hear a synopsis of where exactly the difficulties in reducing biology to chemistry or chemistry to physics are, because in the biology I've studied macroscopic organisms were easily reducible to microscopic organisms, and we've gotten really good at modelling the nanoscopic molecular machinery that those microscopic organisms are made of, which seems like that's already a reduction to chemistry. Likewise, in the chemistry I've studied, all the aggregate chemical reactions were explained in terms of molecule-by-molecule interactions, which appealed ultimately to the physics of electron orbitals for how the atoms of those molecules do their things to each other. At no point in my (admittedly non-specialist) education in these fields were any specific problems where something could not be clearly reduced to something simpler ever detailed, so I'd be curious to hear about some.

I don’t see why we can’t say reason depends on non-physical stuff, if only because reason is itself non-physical — Mww

That's begging the question there. -

Olivier5

6.2kThis is actually a much clearer way of formulating my objection to strong emergentism, so this has turned out to be a productive conversation after all; I'll make a note to myself to phrase it this way in the future. — Pfhorrest

Olivier5

6.2kThis is actually a much clearer way of formulating my objection to strong emergentism, so this has turned out to be a productive conversation after all; I'll make a note to myself to phrase it this way in the future. — Pfhorrest

You might as well, because all this talk about weak and strong emergence is cheap.

The main problem I see with reductionism (the actual name for this idea of yours; an idea from the 19th century) is the elusive bottom: there's no reason to assume that there is some rock bottom somewhere on the path to the infinitely small.

Another problem is that our present understanding of biology contradicts reductionism, in that in a living being, the structure is more important than the elements, and in fact manages its own elements. This is evidence of top-down causation, an anathema for reductionists.

Finally, reductionism is tragically penny-wise dollar-stupid. It makes the quest of truth about some sort of sad bean counting. By that I mean that instead of taking the human condition seriously, it makes gestures in the direction of muons and quarks, assuring us that one day, we will know who we are by looking at our smallest pieces... This is alienating, and may explain the tragedies of the 20th century. After all, if human beings are nothing more than clusters of atoms, one might as well kill them en masse.

Reductionism is a death cult. -

Olivier5

6.2kAt no point in my (admittedly non-specialist) education in these fields were any specific problems where something could not be clearly reduced to something simpler ever detailed, so I'd be curious to hear about some. — Pfhorrest

Olivier5

6.2kAt no point in my (admittedly non-specialist) education in these fields were any specific problems where something could not be clearly reduced to something simpler ever detailed, so I'd be curious to hear about some. — Pfhorrest

The fundamental problem to "jump" from QM to chemistry is that we can't solve the Schrödinger equation for molecules. So we cannot predict, say, the V-shape form of the molecule of water from our QM models of oxygen and hydrogen. The shape of molecules being a big factor in their chemical reactivity (stericity), this means we can't predict chemistry from QM.

The fundamental issue to "jump" from chemistry to life is the problem of abiogenesis. We don't have a good model of how life emerged from non-life. In life, chemistry is instrumentalized to transmit messages, so there is an epistemic jump here, not just an organizational one like exists between QM and chemistry. How chemicals did learn to communicate and coordinate with one another is therefore a major issue.

Then there is the "jump" from biology to consciousness, which is where we happen to live. This is the mind-body problem, and it's not near being solved. I also think of it as an epistemic jump, not just as a more complex form of organisation. The mind is life trying to understand itself. -

Mww

5.4kI don’t see why we can’t say reason depends on non-physical stuff, if only because reason is itself non-physical

Mww

5.4kI don’t see why we can’t say reason depends on non-physical stuff, if only because reason is itself non-physical

— Mww

That's begging the question there. — Pfhorrest

.....says the guy that doesn’t deny human reason, insists it must in no way depend on non-physical stuff, yet can’t measure it. Can’t show how signals from a sense organ enable some quanta of neurotransmitters such that Lima beans are translated into that which the brain registers as gawd-awful. Then, even enables itself to inform some other brain it has registered Lima beans as gawd-awful, with which that other brain may not agree. Maybe because it has no “gawd-awful” pathways enabled....dunno.

I’d rather just beg the question. -

Pfhorrest

4.6kYou might as well, because all this talk about weak and strong emergence is cheap. — Olivier5

Pfhorrest

4.6kYou might as well, because all this talk about weak and strong emergence is cheap. — Olivier5

I'm still talking about weak and strong emergence. Your refusal to acknowledge that we're talking about different things is the root of this entire disagreement. Philosophical progress is made almost entirely by differentiating concepts that would otherwise cause intractable confusion when conflated together.

The main problem I see with reductionism (the actual name for this idea of yours; an idea from the 19th century) is the elusive bottom: there's no reason to assume that there is some rock bottom somewhere on the path to the infinitely small. — Olivier5

Reductionism is much older than the 19th century, and that's not a fault with it; lots of old ideas are still the right ideas. Literally the first ever philosophical theory in recorded history was "maybe everything is made of the same stuff" (water, according to Thales), and that notion that everything is connected in one continuous unified whole has been the driving force behind most of science. It's not about finding a "rock bottom", it's about not having discontinuities in our understanding: having every account or everything transition seamlessly into each other with no sudden new fundamental laws of nature added anywhere, just building up from simpler laws of simpler things, and analyzing those simple laws of simple things down in to even simpler laws of even simpler things. We start in the middle and connect both up and down.

Man, the more I talk about this with you the more I realize my overarching philosophical principles apply to this situation more directly than I thought. Your recourse to strong emergence to avoid the bottomless pit of reductionism is exactly analogous to the transcendental dogmatist who thinks the only alternative to that worldview is cynical relativism (a la "you have to believe in magic or else you believe in nothing"). You're taking a side on a dichotomy that I consider false. I'm not on the opposite side of that dichotomy from you, I reject the dichotomy entirely.

Another problem is that our present understanding of biology contradicts reductionism, in that in a living being, the structure is more important than the elements, and in fact manages its own elements. This is evidence of top-down causation, an anathema for reductionists. — Olivier5

This is still misunderstanding what's even at issue here. What you're talking about is multiple realizability: you can have a high-level structure realized in many different kinds of low-level structures. That doesn't change that all you need to get the high-level structure it to put some such low-level structure or another in place; you don't have to arrange the parts and then wave your magic wand to bring them to life, just arranging any appropriate parts the appropriate way is enough. That different parts can be used to the same effect is beside that point.

Finally, reductionism is tragically penny-wise dollar-stupid. It makes the quest of truth about some sort of sad bean counting. By that I mean that instead of taking the human condition seriously, it makes gestures in the direction of muons and quarks, assuring us that one day, we will know who we are by looking at our smallest pieces... This is alienating, and may explain the tragedies of the 20th century. After all, if human beings are nothing more than clusters of atoms, one might as well kill them en masse.

Reductionism is a death cult. — Olivier5

I've suspected that some kind of attitude like this was behind your recalcitrance. You think that a deeper understanding of something somehow makes it less special, takes away some kind of magic. Never mind that this is completely mixing up is and ought. You can understand that human beings are fundamentally just really complex patterns of excitations in quantum fields, and still also understand that their lives have moral value; because one has nothing to do with the other. -

Olivier5

6.2kYour refusal to acknowledge that we're talking about different things is the root of this entire disagreement. — Pfhorrest

Olivier5

6.2kYour refusal to acknowledge that we're talking about different things is the root of this entire disagreement. — Pfhorrest

This is how it feels from my side:

Olivier5: there exist donkeys.

Pfhorrest: only weak donkeys exist. Strong donkeys are impossible.

O5: ???

Pfh: strong donkeys are those traveling faster than the speed of light. They cannot possibly exist.

O5: mmmmokay... So weak donkeys exist.

Pfh: yes but weak donkeys are trivial. The important point is that strong donkeys do not exist.

.......

I suspect you use this distinction between strong and weak donkeys to muddy the water and avoid facing the existence of real donkeys. Because you and I happen to agree on the impossibility of transluminous donkeys. Where we disagree is where you say "weak emergence is trivial". I believe it is massively important and non trivial, as it created you and me.

Reductionism is much older than the 19th century, — Pfhorrest

They have been precursors, but I think you are confusing reductionism with the idea that nature is one, an idea at least as old as monotheism, and to which I subscribe. But just because nature is one, does not mean there's no emergence in it. A theory of everything would include some description of life, societies, language, literature, science, philosophy, and the likes, and therefore would need to account for their emergence. The TOE won't be just about muons. There is no reason to prioritize one scale of reality over another, which is what reductionists do.

You can understand that human beings are fundamentally just really complex patterns of excitations in quantum fields, and still also understand that their lives have moral value; because one has nothing to do with the other. — Pfhorrest

Quantum fields have moral values? Since when? -

Pfhorrest

4.6kI suspect you use this distinction between strong and weak donkeys to muddy the water and avoid facing the existence of real donkeys. Because you and I happen to agree on the impossibility of transluminous donkeys. Where we disagree is where you say "weak emergence is trivial". I believe it is massively important and non trivial, as it created you and me. — Olivier5

Pfhorrest

4.6kI suspect you use this distinction between strong and weak donkeys to muddy the water and avoid facing the existence of real donkeys. Because you and I happen to agree on the impossibility of transluminous donkeys. Where we disagree is where you say "weak emergence is trivial". I believe it is massively important and non trivial, as it created you and me. — Olivier5

I only mean trivial in the sense that it's not something in dispute. Nobody denies the existence of subluminal donkeys, so there's no point arguing about them. And you and I may exist that there are no superluminal donkeys, but there are other people who claim that they do exist. I suspect that you think it's pointless arguing about whether superluminal donkeys because they obviously don't, but if you agree that that's obvious you're not the target of the argument, the people who think they do exist are. If the only donkey's you're talking about are subluminal ones, I don't know why we're even arguing, and in that sense (the "where's the disagreement?" sense) it's trivial.

However, as the conversation has gone on, it's begun to sound like you really do believe in superluminal donkeys, think all donkeys are superluminal, and take disputing the existence of superluminal donkeys to be equivalent to disputing the existence of donkeys entirely. Or at other times, in the other direction, like you think a "donkey" is just any ungulate. Or possibly both at once, that all ungulates are donkeys and all of them are superluminal, and take my denial of anything superluminal as a denial that even cows exist.

A theory of everything would include some description of life, societies, language, literature, science, philosophy, and the likes, and therefore would need to account for their emergence. The TOE won't be just about muons. — Olivier5

Sure, but the TOE should be able to relate phenomena on any level to phenomena on any other level, in principle, even if it's impractically difficult and not something we'd want to do in the ordinary routine of things. It should be able to describe psychological phenomena in terms of biological phenomena, and biological phenomena in terms of chemical phenomena, and chemical phenomena in terms of physical phenomena. Just like in mathematics, we can in principle describe things as complicated as Special Unity groups (a kind of locally-flat geometric space, obeying certain rules, where every point in that space is a square matrix of complex numbers, also obeying certain rules) entirely in terms of empty sets nested inside of each other.

There's no practical reason why we would want to do that ordinarily, but being able in principle to zoom into the details of someone on one level of abstraction and see a complex arrangements of things on another lower level means we never have any discontinuities in our understanding of things: we can understand how all of these different kinds of objects at different scales relate to each other. Weak emergence is just the converse of that: if you zoom out and ignore the details on the smaller scale you'll begin to see new structures on a larger scale, just as a natural consequence of those smaller-scale things doing what they do. Strong emergence OTOH is the claim that those higher-level structures are not such a natural consequence: that there are special higher-level rules that explicitly cause those higher-level structures to exist, and as a consequence if you zoom in too far ("reductionism") you lose information.

It would perhaps be handle to speak also of "weak reductionism" and "strong reductionism", where weak reductionism is compatible with weak emergentism and vice versa, while strong reductionism is incompatible with strong emergentism and vice versa. Which once again fits the kind of pattern that comes up over and over again in my general philosophy:

etc

Quantum fields have moral values? Since when? — Olivier5

Patterns of information encoded in quantum fields have moral value (singular, i.e. are of moral value) since they developed into forms that differentiate the experiences they are subjected to into types with different directions of fit, thereby becoming susceptible to suffering upon mismatch of those experiences. -

Olivier5

6.2kbeing able in principle to zoom into the details of someone on one level of abstraction and see a complex arrangements of things on another lower level means we never have any discontinuities in our understanding of things: we can understand how all of these different kinds of objects at different scales relate to each other. — Pfhorrest

Olivier5

6.2kbeing able in principle to zoom into the details of someone on one level of abstraction and see a complex arrangements of things on another lower level means we never have any discontinuities in our understanding of things: we can understand how all of these different kinds of objects at different scales relate to each other. — Pfhorrest

No disagreement there, as long as the specificity of each level is adequately and equally reflected, rather than abolished. There is no level having some greater existence or causality than another. They are all just one reality. The different scales are a view of the mind and therefore no particular scale takes precedence over the others in reality.

We might think of our level as the "ground level" or reference level for instance. We often do, in fact, but that is just because it is literally our point of view, our locus of experience. It's how the world looks from where we are. If the universe could think, it would probably see itself, the whole universe, as the "ground level" and everything else as mere details.

Weak emergence is just the converse of that: if you zoom out and ignore the details on the smaller scale you'll begin to see new structures on a larger scale, just as a natural consequence of those smaller-scale things doing what they do. Strong emergence OTOH is the claim that those higher-level structures are not such a natural consequence: that there are special higher-level rules that explicitly cause those higher-level structures to exist, and as a consequence if you zoom in too far ("reductionism") you lose information. — Pfhorrest

Rather, I see a new structure as one of the many possible manners in which certain elements could be arranged to do things these elements cannot do in isolation. Structures are not pre-determined, they just happen a certain way but could have happened another way. And structures do things that don't "show up" at elemental level. For instance, you cannot observe or describe phenomena like reproduction or predation at elementary particle level. Of course, when you eat a carrot (or use it to simulate or stimulate reproduction) certain things happen to the electrons of that carrot, but if you'd zoom on them, you won't see your electrons eating up the carrot's electrons or shaging them. You wouldn't see anything in fact, because that's not the level at which predation or reproduction happens. It is in this sense that reductionism is absurd. -

Olivier5

6.2kThe important point being that there is no level having some greater causality or existence than another. Reductionism is needlessly micro-centric.

Olivier5

6.2kThe important point being that there is no level having some greater causality or existence than another. Reductionism is needlessly micro-centric. -

Pfhorrest

4.6kIf that’s your point, it’s completely beside my point.

Pfhorrest

4.6kIf that’s your point, it’s completely beside my point.

Emergence came up in this thread in the course of making the point that the higher and lower level structures are metaphysically continuous, such that the higher level can be broken down to the lower level and the lower level built up into the higher level and at no point do all new metaphysics have to be invoked: it’s all the same kind of stuff, examined at different levels of detail or abstraction. Strong emergentism definitionally runs counter to that. If you’re not counter to that, then I’m not arguing against you. As I’ve been saying all along. -

Olivier5

6.2kTypically, there are ethical consideration for human beings, which are not needed for rocks or even for plants and lower animals. This would need a recognition that human beings do bring something new to the picture: ethical considerations (among others).

Olivier5

6.2kTypically, there are ethical consideration for human beings, which are not needed for rocks or even for plants and lower animals. This would need a recognition that human beings do bring something new to the picture: ethical considerations (among others).

When I asked you since when wavefunctions have moral values, you answered in essence: since they can suffer. Can't electrons suffer? Is suffering an emerging phenomenon then?

My whole problem with reductionism is that it is alienating. It places truth and causality artificially and needlessly outside of the human realm. It makes a mockery of human beings. Hence the people adopting it become sad, depressed and often aggressive. I believe it is important to recognize a certain sanctity to the human person. The idea comes from religion: man was supposedly made in the image of God. Even an atheist such as myself can see in the 20th century the horrors that the trivialization of human beings as mere objects can bring. God was dead alright, and man was expandable.

There is something radically new in life, and in human consciousness. Something precious and rare that does not exist in electrons.

Philosophies have consequences. A philosophy that does not see life as precious and does not recognize human beings as specially precious, is a dangerous philosophy. If your form of reductionism is not like that, if it can find ways to calculate moral values based on the Schrödinger equation, maybe indeed it is a weak form of reductionism, one that allows quite a lot of emergence to happen in it. -

Pfhorrest

4.6kIf your form of reductionism is not like that, if it can find ways to calculate moral values based on the Schrödinger equation — Olivier5

Pfhorrest

4.6kIf your form of reductionism is not like that, if it can find ways to calculate moral values based on the Schrödinger equation — Olivier5

It isn't like that, but not because it can "calculate moral values based on the Schrödinger equation", but because questions about what is real and questions about what is moral are completely separate kinds of questions, on my account. Analyzing what a human being (or anything) is, down into quantum fields or whatever, tells us nothing one way or the other about what ought to be; the answers to the latter question are independent of answers to the former question.

And that's not strongly emergent, because it's not that new "ethical properties" arise when amoral matter is arranged the right way, but that ethical questions are completely separate from what kinds of properties what kinds of things have and how they relate to each other.

Welcome to The Philosophy Forum!

Get involved in philosophical discussions about knowledge, truth, language, consciousness, science, politics, religion, logic and mathematics, art, history, and lots more. No ads, no clutter, and very little agreement — just fascinating conversations.

Categories

- Guest category

- Phil. Writing Challenge - June 2025

- The Lounge

- General Philosophy

- Metaphysics & Epistemology

- Philosophy of Mind

- Ethics

- Political Philosophy

- Philosophy of Art

- Logic & Philosophy of Mathematics

- Philosophy of Religion

- Philosophy of Science

- Philosophy of Language

- Interesting Stuff

- Politics and Current Affairs

- Humanities and Social Sciences

- Science and Technology

- Non-English Discussion

- German Discussion

- Spanish Discussion

- Learning Centre

- Resources

- Books and Papers

- Reading groups

- Questions

- Guest Speakers

- David Pearce

- Massimo Pigliucci

- Debates

- Debate Proposals

- Debate Discussion

- Feedback

- Article submissions

- About TPF

- Help

More Discussions

- A diary entry of mine regarding free will, determinism and its implication for morality

- Reasoning badly about free will and moral responsibility

- The Free Will prob:Distinguishing the relevance of the quest'n of moral over that of amoral autonomy

- The Importance of Divine Hiddenness for Human Free Will and Moral Growth

- Other sites we like

- Social media

- Terms of Service

- Sign In

- Created with PlushForums

- © 2026 The Philosophy Forum