-

Pfhorrest

4.6kAs already detailed in my previous thread on dissolving normative ethics, I take the usual different and competing approaches to normative ethics to be better viewed as different, mutually compatible answers to meta-ethical questions, e.g. deontological ethics leans toward a good answer to a question about something like moral epistemology, and consequentialist or teleological ethics leans toward a good answer to a question about something like moral ontology.

Pfhorrest

4.6kAs already detailed in my previous thread on dissolving normative ethics, I take the usual different and competing approaches to normative ethics to be better viewed as different, mutually compatible answers to meta-ethical questions, e.g. deontological ethics leans toward a good answer to a question about something like moral epistemology, and consequentialist or teleological ethics leans toward a good answer to a question about something like moral ontology.

In this thread I'd like to discuss the latter.

Teleology (from the Greek word telos, meaning "purpose") is often taken to be the study of purpose as it serves a role in descriptive, causal explanations of reality: looking at the ends to which things serve as means for an explanation of why those things came to exist, on the assumption that they were created by something to serve those ends. That is not the sense in which I mean the term here. Less often, teleology is taken to be the study of purpose in a prescriptive, moral sense, as in the ends toward which we aim our actions, the good that we seek to bring about. That is the sense in which I mean the term here.

Normative ethical models that concern themselves primarily with the ends or consequences brought about by actions are sometimes called teleological, though they are more often called consequentialist. And though I do not endorse such teleological models of normative ethics over other models, I do consider the ends or consequences brought about by actions to be one important aspect of morality worth consideration, and I use the term "teleology" here to denote the study of that aspect.

I consider this field something like moral ontology, but not literally, as I hold ontology to be entirely a descriptive matter and all moral topics to be entirely prescriptive matters, so strictly speaking, on my account, there is no ontology of anything to do with morality. But just as ontology is about the objects of reality, teleology in this sense is about the objects of morality, in the sense of the word "object" that means purpose, end, aim, or goal: it is about the states of affairs to be sought after and brought about by moral actions.

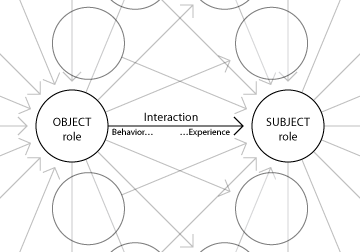

As explained in my earlier thread on the web of reality, I hold the fundamental constituents of reality to be what Alfred North Whitehead called "occasions of experience", but I elaborate upon that concept, holding those experiences to be fundamentally interactions that can equally be seen, from a different perspective, as behaviors: the behavior of various things upon another thing constituting the experience that thing has of the various other things; each thing being defined by the function from its experiences to its behaviors, the experiences constituting the input to that function and the behaviors constituting the output.

While most of the preceding threads reality and knowledge I've started here have concerned that experiential input to our own functions, this one and those that will follow about morality and justice instead concern the behavioral output of our functions.

As ontology is about the kinds of things that really do exist and the kinds of events that really do occur, that are the causes of our experiences, so too teleology in this sense is about the kinds of things that morally ought to exist and the kinds of events that morally ought to occur, that are the purposes of our behaviors. In this sense, purpose is the prescriptive analogue of the descriptive ontological concept of causation: cause is about why something does happen, while purpose is about why something should happen.

(Aristotle actually considered these two different senses of the Greek word for cause, differentiating them as the "efficient cause" and "final cause", along with what he called "formal cause" and "material cause" which were what we would today call just "form" and "substance".)

Similarly, the prescriptive analogue of the descriptive ontological concept of substance is wealth: wealth is stuff of value. And just as in my ontology I hold real objects of substance to be constituted by the things they cause to happen (ala "to be is to do"), so too I hold that the value of wealth is constituted by the purpose that it serves: a thing is of value for the good that can be done with it.

This concept of wealth can be further decomposed into concepts of capital and labor, which in turn can be further decomposed to familiar ontological categories: capital is of value for the matter and space that it provides, while labor is of value for the energy and time that it provides. And just as matter is ultimately reducible to energy, so too capital is ultimately reducible to labor: capital is the distilled product of labor, worth at least the minimal time and energy it takes to obtain or create, and no more than the maximal time and energy it can save elsewhere.

Similarly, just as physical work happens when matter and energy flow through space and time, what we might call "ethical work" happens – good gets done – when wealth flows in an economy, each kind of wealth diffusing from where it is in higher concentration to where it is in lower concentration. The similarities between physical and economic systems are explored in more detail in the economic fields of thermoeconomics or more generally econophysics.

And lastly, I hold that the prescriptive analogue of the descriptive ontological concept of "mind", in the sense of "phenomenal consciousness" as elaborated in my previous thread on philosophy of mind, is a sense of "will" that will be further elaborated upon in a later thread on the will. These two things are about the "subjects", rather than the "objects", of reality and morality, respectively.

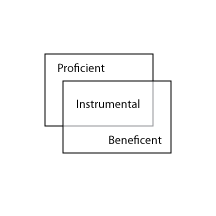

Just as in my previous thread about ontology I distinguished between concrete existence and abstract existence, deferring discussion of abstract existence to my even earlier thread about the existence of mathematical objects, so too I need to briefly distinguish between two types of goods here, which I will called "beneficent" and "proficient". By proficient goods, I mean things that are good in the sense of being good at or good for something, without any regard for whether that something is in itself an intrinsically good thing, in the usual moral sense; and by beneficent goods, in contrast, I mean things that are intrinsically good in themselves.

I do not draw a sharp division between all goods into one of these two categories, but rather hold them to overlap significantly, with the vast majority of good things being good for their proficiency at bringing about beneficence; in much the same way that, in ontology, I hold that most of the things we consider real are to some extent abstractions, that are nevertheless real inasmuch as they explain more concrete phenomena.

And just as I defer to my thread about mathematical objects for discussion of purely abstract existence, so too I defer now back to my earlier thread about rhetoric and the arts for discussion of purely proficient goods.

Later in this thread, or possibly in a subsequent thread, I am (finally) going to discuss the topic of beneficent goods, by which I mean hedonic goods, the kinds of goods that sate our experiential appetites; as well as the proficient goods that at least indirectly serve those same hedonic ends, what we might call instrumental goods.

But this OP is long enough already and this is kind of a natural break between talking about the nature of the field I'm going to discuss, and talking about my actual views in that field. -

Joshs

6.7kThis is a well articulated description of a dualist-based model of moral reasoning, replete with a separation of the affective-hedonic, the cognitive-rational and the conative aspects of human functioning, along with a split between the subjective and objective, and the ‘is’ and the ‘ought’.

Joshs

6.7kThis is a well articulated description of a dualist-based model of moral reasoning, replete with a separation of the affective-hedonic, the cognitive-rational and the conative aspects of human functioning, along with a split between the subjective and objective, and the ‘is’ and the ‘ought’.

The usual blind spots in making sense of human behavior are to be expected from such a traditional model. -

Pfhorrest

4.6kI wouldn’t call myself “dualist” in the usual ontological sense: I am a strong monist (physicalist phenomenalist) about ontology. I’m not proposing the existence of nonphysical beings or substances or properties here, but rather drawings attention to the prescriptive equivalents of such descriptive ontological things.

Pfhorrest

4.6kI wouldn’t call myself “dualist” in the usual ontological sense: I am a strong monist (physicalist phenomenalist) about ontology. I’m not proposing the existence of nonphysical beings or substances or properties here, but rather drawings attention to the prescriptive equivalents of such descriptive ontological things.

What sense of “dualism” do you mean, and what are the blind spots you speak of? I strongly suspect that they are not applicable to what I mean here, as this is not at all a traditional model; at least, I never learned of anything like it in the course of my philosophy degree. -

Joshs

6.7kWhat sense of “dualism” do you mean, and what are the blind spots you speak of? — Pfhorrest

Joshs

6.7kWhat sense of “dualism” do you mean, and what are the blind spots you speak of? — Pfhorrest

This is my suggested route to transcending dualistic tendencies:

Rather than distinguishing between what ‘is’ and what ‘ought to be’, recognize with Putnam, Rorty and others the inseparability of fact and value, description and prescription

Recognize that affectivity( the hedonic) is not separable from rationality but forms the core of intentional meaning.

Understand that both subjectivity and objectivity are constructed through intersubjective processes. Instead of the computer-based metaphor of the subjective agent receiving inputs from objective sense data and transforming this into behavioral output, see the organism-environment relation as a single system of of mutual transformation. Another way of saying this is that our propositions do not meet up with an independent nature but only with other propositions( ‘nature’ filtered though our purpose -driven interpretations of it). -

Pfhorrest

4.6kRather than distinguishing between what ‘is’ and what ‘ought to be’, recognize with Putnam, Rorty and others the inseparability of fact and value, description and prescription — Joshs

Pfhorrest

4.6kRather than distinguishing between what ‘is’ and what ‘ought to be’, recognize with Putnam, Rorty and others the inseparability of fact and value, description and prescription — Joshs

I recognize that there is a descriptive and prescriptive facet to everything, and that they are abstractions from a single experiential-behavioral process; that to non-sentient beings, every experience is simultaneously informative and motivational and directly leads to a subsequent behavior. But it is precisely the ability to differentiate those aspects, setting aside some kinds of experiences as merely informative, some as merely motivational, then reflecting on both of the models thereby generated, before then combining those "is" and "ought" thoughts (beliefs and intentions) together to drive behavior, that constitutes sentience (and sapience) itself. (As discussed in my thread on philosophy of mind).

Recognize that affectivity( the hedonic) is not separable from rationality but forms the core of intentional meaning. — Joshs

I'm not making a distinction between the hedonic and the rational, except to the same degree as the empirical and the rational; empiricism and hedonism are both about experiences (distinguished by direction of fit), while rationality is a structure of thinking about both, where everything we think is about those experiences. It's all one multidimensional continuum, but analyzing the different dimensions and directions in that continuum is what philosophy is for.

NB from the preceding thread:

In general, I view the correct approach to prescriptive questions about morality and justice to be completely analogous to, but also entirely separate from, the correct approach to descriptive questions about reality and knowledge. This is different from views that hold that one set of questions reduces entirely to the other set of questions, like both scientism (which reduces prescriptive questions to descriptive ones) and constructivism (which reduces descriptive questions to prescriptive ones).

But it is also different from views such as the "non-overlapping magisteria" proposed by Stephen Jay Gould, who held that questions about reality are the domain of science, with its methodologies, while questions about morality were entirely separate in the domain of religion, with its wholly different methodologies.

I hold, like Gould, that they are entirely separate questions, but that perfectly analogous, broadly-speaking scientific, methodologies can be applied to each, and that religious methodologies have historically been (wrongly) applied to both of them as well. This is largely because of my views that prescriptive assertions and opinions are generally analogous in every way to descriptive assertions and opinions, differing only in a quality called "direction of fit". — Pfhorrest

More on that direction-of-fit basis in my earlier thread about metaethics and philosophy of language.

Understand that both subjectivity and objectivity are constructed through intersubjective processes. Instead of the computer-based metaphor of the subjective agent receiving inputs from objective sense data and transforming this into behavioral output, see the organism-environment relation as a single system of of mutual transformation. — Joshs

In my ontology (already linked in the OP) I do explicitly acknowledge that already. All objects are subjects, all subjects are all objects, every experience is of something else's behavior, and every behavior constitutes something else's experience, experience and behavior being different perspectives on the same thing, an interaction. That's why in the diagram in the OP, the two things represented by circles are labelled "object role" and "subject role", to show that the interaction is a behavior of the thing considered as an object, and an experience from the perspective of the thing considered as a subject, and it's which role they're being considered in (which perspective we're taking) that determines which end of the interaction is experiential and which is behavioral.

But again, it's analyzing the different facets of these compound things that gives us greater insight into them. We could just de-analyze everything to "stuff happening" in the extreme other direction, but it's the distinctions that make for a philosophical examination. -

Joshs

6.7kIn reading your current op as well as previous threads, I notice that, while you reference writers like Jackson, Block and Chalmers , there seems to be no engagement with phenomenological philosophy and those researchers of consciousness who have been strongly influenced by it( Zahavi, Varela and Thompson), or writers coming from the radical constructivist tradition ( Von Glasersfeld, Maturana, Piaget) or embodied enactivist perspectives( Gallagher, Fuchs).

Joshs

6.7kIn reading your current op as well as previous threads, I notice that, while you reference writers like Jackson, Block and Chalmers , there seems to be no engagement with phenomenological philosophy and those researchers of consciousness who have been strongly influenced by it( Zahavi, Varela and Thompson), or writers coming from the radical constructivist tradition ( Von Glasersfeld, Maturana, Piaget) or embodied enactivist perspectives( Gallagher, Fuchs).

Instead I see formulations reminiscent of 1st generation cognitivism and representationalism , with the accompanying metaphor of mind as computer ( the mind inputs i interpreted sense dat and processes into output) with a bit of ‘subjective 1st person coloration sprinkled over it. For instance , you write “ Sensations are the raw, uninterpreted experiences, like the seeing of a color, or the hearing of a pitch.” That a classic dualistic move.

It seems to me this way of modeling conscious activity misses the fundamentally normative( an organism’s ‘is’ is anticipative in that it’s world matters to it in particular ways in relation to it’s functioning , and it evinces an inherently prescriptive , purposive and holistic character of experiencing at all levels. -

Pfhorrest

4.6kthere seems to be no engagement with phenomenological philosophy and those researchers of consciousness who have been strongly influenced by it( Zahavi, Varela and Thompson), or writers coming from the radical constructivist tradition ( Von Glasersfeld, Maturana, Piaget) or embodied enactivist perspectives( Gallagher, Fuchs). — Joshs

Pfhorrest

4.6kthere seems to be no engagement with phenomenological philosophy and those researchers of consciousness who have been strongly influenced by it( Zahavi, Varela and Thompson), or writers coming from the radical constructivist tradition ( Von Glasersfeld, Maturana, Piaget) or embodied enactivist perspectives( Gallagher, Fuchs). — Joshs

That would because I'm completely unfamiliar with them, which surprises me as if they're notable I'd have expected to have at least heard of them briefly in the course of my degree. Can you give me an overview of the general kind of view they represent? I'm always interested to learn more. (I did a quick scan through all their wikipedia articles and didn’t see anything that jumped out as objectionable to me).

Instead I see formulations reminiscent of 1st generation cognitivism and representationalism — Joshs

I am generally a cognitivist, though I'm not sure in what domain you mean that; in meta-ethics specifically (where I'm most familiar with that term) I'm specifically a non-descriptive cognitivist, which is a position that does not seem well known, that I arrived at independently myself after being unsatisfied with the spread of options presented to me, but which I've since discovered was also put forth a few years before me in 2000 by Terry Horgan and Mark Timmons.

However I am strongly anti-representationalist, if you mean that in the epistemological sense. I am a direct realist. I mentioned that in the previous thread:

This is similar to how my views on ontology and epistemology (see links for previous threads) entail a kind of direct realism in which there is no distinction between representations of reality and reality itself, there is only the incomplete but direct comprehension of small parts of reality that we have, distinguished from the completeness of reality itself that is always at least partially beyond our comprehension. We aren't trying to figure out what is really real from possibly-fallible representations of reality, we're undertaking a fallible process of trying to piece together our direct sensation of small bits of reality and extrapolate the rest of it from them. — Pfhorrest

with the accompanying metaphor of mind as computer ( the mind inputs i interpreted sense dat and processes into output) with a bit of ‘subjective 1st person coloration sprinkled over it — Joshs

It's not supposed to be specifically a computer metaphor, but an account of everything, not just minds, in terms of mathematical functions: things are what they do, specifically in response to what is done unto them, as what they do is what we experience of them, and conversely what is done unto them is what they experience and respond to.

To quote from that ontology thread just linked above:

George Berkeley famously said that "to be is to be perceived", and I don't agree with that entirely, in part because I take perception to be a narrower concept than experience in a broader sense, and because I don't think it is the actual act of being experienced per se that constitutes something's existence, but rather the potential to be experienced. I would instead say not that to be is to be perceived, or that to be is to be experienced, but that to be is to be experienceable.

And I find this adage to combine in very interesting ways with two other famous philosophical adages: Socrates said that "to do is to be", meaning that anything that does something necessarily exists; and more poignantly, Jean-Paul Sartre said that "to be is to do", meaning that what something is is defined by what that something does. Being, existence, can be reduced to the potential for or habit of some set of behaviors: things are, or at least are defined by, what they do, or at least what they tend to do. (Coupled with the association of mass to substance and energy to causation, this notion that to be is to do seems to me a vague predecessor to the notion of mass-energy equivalence).

To combine this with my adaptation of Berkeley's adage, we get concepts like "to do is to be experienced", "to be experienced is to do", "to be done unto is to experience", and "to experience is to be done unto".

This paints experience and behavior as two sides of the same coin, opposite perspectives on the same one thing: an interaction. Our experience of a thing is that thing's behavior upon us. An object is red inasmuch as it appears red, and it appears red inasmuch as it emits light toward us in certain frequencies and not others: the emission of the right frequencies of light, a behavior in a very broad sense, constitutes the property of redness. Every other property of an object is likewise defined by what it does, perhaps in response to something that we must do first: an object's color may be relative to what frequencies of light we shine on it (e.g. something that is red under white light may be black under blue light), the shape of the object as felt by touch is defined by where it pushes back on our nerves when we press them into it, and many other more subtle properties of things discovered by experiments are defined by what that thing does when we do something to it.

We can thus define all objects by their function from their experiences to their behaviors: what they do in response to what it done to them. The specifics of that function, a mathematical concept mapping inputs to outputs, defines the abstract object that is held to be responsible for the concrete experiences we have. Every object's behavior upon other objects constitutes an aspect of those other objects' experience, and every object's experience is composed of the behaviors of the rest of the world upon it. — Pfhorrest

For instance , you write “ Sensations are the raw, uninterpreted experiences, like the seeing of a color, or the hearing of a pitch.” That a classic dualistic move. — Joshs

This still seems like some unfamiliar sense of "dualism" to me. Can you elaborate more on what you mean by it? At first I thought you meant the familiar ontological dualism, i.e. material things vs mental things. I am strongly against that. Then I thought you meant the "dualism" of the is/ought or fact/norm distinction, but the above doesn't seem related to that. So I have no idea what you mean now. -

Gregory

5k

Gregory

5k

Teology is a blurry question. Do you believe homosexuality bad and straight sex good?

In a moment of conscience the "law" is objective, but maybe everyone has different situational experiences -

Gregory

5kteleology is taken to be the study of purpose in a prescriptive, moral sense, as in the ends toward which we aim our actions, the good that we seek to bring about. That is the sense in which I mean the term here. — Pfhorrest

Gregory

5kteleology is taken to be the study of purpose in a prescriptive, moral sense, as in the ends toward which we aim our actions, the good that we seek to bring about. That is the sense in which I mean the term here. — Pfhorrest

Saying we apply morality to ourselves refers to my second my point. My first point was that Greek teleology leads directly to: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=rynlfggqAcU -

Pfhorrest

4.6kSaying we apply morality to ourselves refers to my second my point. — Gregory

Pfhorrest

4.6kSaying we apply morality to ourselves refers to my second my point. — Gregory

Still not following.

My first point was that Greek teleology leads directly to: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=rynlfggqAcU — Gregory

I'm not gonna watch almost 2hrs of video to get your point here, can you summarize for me? -

god must be atheist

5.1kThe opening post was way above my pay-grade. I can't understand a single notion described in it, even if I read it. -

Gregory

5k

Gregory

5k

I agree. I thought his point was that we know morality from the purpose of functions. If this is true, than we would know the morality of sexuality from its function and thus the position advocated by Dr. Feser would seem to infallibly follow. I don't śee how the idea of "purpose" can be anything but subjective, but maybe Pfhorrest has a more subtle point to make -

Pfhorrest

4.6kI thought his point was that we know morality from the purpose of functions. If this is true, than we would know the morality of sexuality from its function and thus the position advocated by Dr. Feser would seem to infallibly follow. — Gregory

Pfhorrest

4.6kI thought his point was that we know morality from the purpose of functions. If this is true, than we would know the morality of sexuality from its function and thus the position advocated by Dr. Feser would seem to infallibly follow. — Gregory

Okay, I think I see the confusion here.

In my ontology, previously discussed, I argue that what a thing is at all boils down entirely to its function, in the mathematical sense of a mapping from inputs to outputs, where in this case the inputs are its experiences, what happens to it, and its outputs are its behaviors, what it does; what it does in response to what happens to it, basically. I don't at all mean "function" as in "the function of a vagina is to receive sperm"; that is a thing that it can do, and so is at least a part of the definition of what it is, but that doesn't at all tell us what it should be used for.

The question of "what X should be used for" is, I'm claiming here, the most useful sense of the word "purpose" -- one divorced from any agent-centric explanation of how X came to be, one that doesn't depend on someone having created X "on purpose", but just something good that X can do -- and thus, the analogous feature to "what X even is". The ontological question, about what X is, boils down to (on my aforementioned account) a question of what it does in response to what is done to it, a question of causes and effects; this teleological question, about what X should be used for, is a question of what X should do and what should be done to it to prompt that response, a question of means and ends. One is the question of what causes X to be, and the other is the question of what purpose there is for X to be, which once again doesn't mean "what did someone make X for?", but only "what good can X do?".

So to use your example, "what is the purpose of sex?" boils down to "what is sex good for?", i.e. "what good ends can come about by means of sex?" One of those things could be reproduction, sure, if reproduction is good; another could just be the momentary pleasure, if pleasure is good; etc. It all hinges on what things are good, and what things sex can bring about.

I have a continuation of the OP in the wings that I saved for a followup post or maybe another thread entirely, about how to go about gauging what states of affairs are good, and thus, what the purpose of anything is. But I cut that short because the OP was getting too long already, so for now the rest of the OP is just exploring that analogy further:

- Substance is stuff that is real (for some cause).

- Wealth is stuff that is good (for some purpose).

- Substance can by analyzed in terms of matter-energy and space-time.

- Wealth can be analyzed in terms of capital (matter+space) and labor (energy+time).

- Work in the physical sense (stuff really happening) happens when substances move around.

- Work in an "ethical" sense (good stuff happening) happens when wealth move around.

- Abstractly real stuff is instrumental in the explanation of concretely real stuff.

- Proficient goodness is instrumental in the attainment of beneficent goodness.

Etc. -

Gregory

5k

Gregory

5k

I get where you are coming from, or at least it sounds like Stoicism to me, which is much like my position. Do you yourself see similarities with your thesis and Stoicism? -

Gregory

5k

Gregory

5k

Stoics speak of purpose and such in nature, and of us as nature. They are not as specific as the Catholics though (Feser) for whom contraception is forever forbidden and masturbation a mortal sin -

Pfhorrest

4.6kStoics speak of purpose and such in nature, and of us as nature. — Gregory

Pfhorrest

4.6kStoics speak of purpose and such in nature, and of us as nature. — Gregory

I think I see the connection you mean now. I only half-agree with the Stoics in their "just go with the flow and do what you're meant to do by nature" attitude. (Half as in "the serenity to accept the things I cannot change", but half not as in "the courage to change the things I can" -- and yeah I know that's Christian not Stoic, but the first part of it is very Stoic in character).

I don't think that there's any one specific purpose that is given by "God or Nature" (to borrow Spinoza) to something/someone that it/they must do to be good. Sort of the opposite of that, kind of. We start out not knowing much of anything about what the purpose of anything is, because we start out completely ignorant of what specifically is a good state of affairs, just some criteria by which to judge what's good (which is the topic of the second part of the OP that I trimmed for length), and then from there we fallibly set out to figure out what good can be done by what means, and so discover what the purpose of anything is. -

Gregory

5k

Gregory

5k

The Stoics with their Stoa (a word I found in Nietzsche with respect to them) are like Greek Daoists to me. They are good but they don't tell the full story.

What I meant above about "imposing morality on ourselves" is that we seem to contain an infinity of potentiality inside us and are forced by something elsewhere inside us to impose some of these potentials on ourselves in the form of "laws". I realized this fact when I was studying Fitche. A relevant quote to this is from Hegel: " The will that is genuinely free, and contains freedom of choice sublated (canceled-while-preserved in new form) within itself, is conscious of its content as something steadfast in and for itself; and at the same time it knows the content to be utterly its own." -

Pfhorrest

4.6kThe Stoics with their Stoa (a word I found in Nietzsche with respect to them) are like Greek Daoists to me. They are good but they don't tell the full story. — Gregory

Pfhorrest

4.6kThe Stoics with their Stoa (a word I found in Nietzsche with respect to them) are like Greek Daoists to me. They are good but they don't tell the full story. — Gregory

Agreed. Stoicism, Daoism, and Buddhism all have the "accept the things you cannot change" side of the equation right. In practice their practitioners often do also have the "courage to change the things they can" part down too, but from what I've read of them that's not emphasized so much in the teachings.

What I meant above about "imposing morality on ourselves" is that we seem to contain an infinity of potentiality inside us and are forced by something elsewhere inside us to impose some of these potentials on ourselves in the form of "laws". I realized this fact when I was studying Fitche. A relevant quote to this is from Hegel: " The will that is genuinely free, and contains freedom of choice sublated (canceled-while-preserved in new form) within itself, is conscious of its content as something steadfast in and for itself; and at the same time it knows the content to be utterly its own." — Gregory

I'm not completely sure I understand you, but if I do, then I think I agree. That's actually sort of the thesis of the next topic I'm planning to do after I finish this one (including the second half of the OP that was cut for space): free will, and how it's pretty much equivalent to the capacity for moral judgement; how to will something is the same as to think that it is good, to not only want it, but to judge that it is correct to want and so want to want it; and how freedom of will is for that kind of self-judgement to be causally effective on your behavior, such that your behavior is directed as you reflectively judge that it should be, rather than just blindly in response to outside influences.

Welcome to The Philosophy Forum!

Get involved in philosophical discussions about knowledge, truth, language, consciousness, science, politics, religion, logic and mathematics, art, history, and lots more. No ads, no clutter, and very little agreement — just fascinating conversations.

Categories

- Guest category

- Phil. Writing Challenge - June 2025

- The Lounge

- General Philosophy

- Metaphysics & Epistemology

- Philosophy of Mind

- Ethics

- Political Philosophy

- Philosophy of Art

- Logic & Philosophy of Mathematics

- Philosophy of Religion

- Philosophy of Science

- Philosophy of Language

- Interesting Stuff

- Politics and Current Affairs

- Humanities and Social Sciences

- Science and Technology

- Non-English Discussion

- German Discussion

- Spanish Discussion

- Learning Centre

- Resources

- Books and Papers

- Reading groups

- Questions

- Guest Speakers

- David Pearce

- Massimo Pigliucci

- Debates

- Debate Proposals

- Debate Discussion

- Feedback

- Article submissions

- About TPF

- Help

More Discussions

- Other sites we like

- Social media

- Terms of Service

- Sign In

- Created with PlushForums

- © 2026 The Philosophy Forum