-

noAxioms

1.7k

noAxioms

1.7k

Did they have feet? Did anything (back then) treat dinosaur feet as a particular? To the dinosaur, probably not. If it steps on something sharp, it might perceive that it hurts down there and to back off the further bearing of weight, but that's it. There's no no reason to draw a line where 'foot' is no longer applicable and 'rest of leg' comes into play. That's a complex model of a body with distinct parts all hooked together, and the dinos probably didn't work with such needlessly complex models. Maybe I'm wrong about this.Thus there was a time dinosaurs weren't conditioned by the human understanding. But they still had properties and stuff. Like they had teeth and bowel movements. They had feet. — fdrake

They likely did have concepts of some parts. There's this stegosaurus over there and one wants to maintain awareness of the Thaginator, the most dangerous end of it. That's a particular that both of them might model as a particular thing.

The chemistry examples are good. Chemistry, at a basic level, treats molecules as objects. At least small molecules. For big ones, the objects become more like receptor sites and such, and we start getting into semiotics when working at that level.

Another good point. Demarcation where the rules change. That's better than just 'if I pull here, the object is what all comes along with it', which is a difficult definition to apply. I cannot define a tree that way, because who knows where it will break when I pull hard enough. I might get an entire stand of trees if I pull in the right place, or I might get only a twig.Or I suppose you bite the bullet and make all of natures' processes effectively arbitrarily demarcated from each other. Even when they have different laws and levels.

Sort of. The momentum transfer there is almost the same whether the truck is empty, or loaded with double its unladen mass. It can almost be modelled as a car hitting a somewhat malleable brick wall.The process there is a collision, and in terms of momentum transfer the truck+load is the relevant object.

Yes. There's purpose to that activity, making it normative.But for the process of unloading the truck, the truck+load behaves as a truck with a load in it.

I will try to find this one. Yes, it seems relevant. I looked at the table of contents, if not chapter abstracts. First try: trip to the library.One of the books I was singing the praises of a couple of years back was Mind and the Cosmic Order, Charles Pinter. He’s a maths emeritus (now deceased although he lived until a ripe old age. I wrote to him about his book in 2022 and got a nice reply.) It’s not a fringe or new-age book, it’s firmly grounded in cognitive science and empiricism. A glance at the chapter abstracts in the link will convey something of its gist. — Wayfarer

I don't think 'a view from nowhere' is particularly coherent in our physics. An objective description may well be coherent, but it isn't a view. A picture cannot be drawn from it. Such seems to be the nature of our physics. I think this objective description is what is being sought, but anybody who calls it a view is going down the wrong path.It’s about the fact that science is conducted by humans, who are subjects of experience, who are attempting to arrive at the purported ‘view from nowhere’ which is believed to be something approaching complete objectivity — Wayfarer

That's an easy one; it would be the tree in its entirety that turns to gold. — NotAristotle

Why is that the answer? Why is it easy that the other answers are wrong? What if the twig was the intent? How did Midas not touch the forest?These explanations are sufficient. To touch a branch of a tree is to touch a tree. No confusion there. — L'éléphant

OK, so it's an attachment thing, but the tree is attached to the ground, and thus to the other trees, no? It wouldn't break if I lifted it by the trunk if it wasn't attached so.The twig is a portion of the tree, and the set of the latter is the density that makes up a forest. If Midas touches a twig, everything turns gold unintentionally because each element is interdependent. It would be different if Midas cut a twig with another object (like an axe) and then touched it. Once an element has been lost, the chain of turning into gold is no longer present. — javi2541997

Well, the difficulty isn't there for us because we have language and conventions. It isn't difficulty for physics because physics doesn't care. It has not need for it. It seems only a difficulty for fictions, and it's no problem of mine that not all fictions correspond to a meaningful reality. It's a problem for me only as an illustration of how people accept such impossibilities as sufficiently plausible that they're not even questioned.I am beginning to believe that you are contriving, intentionally or unintentionally, a difficulty that is not there. — L'éléphant

We lost sight of the twig because of the tree. How is that different?Right. Just because everything is touching, like the tree touches the Forrest floor, etc, doesn’t mean you lose sight of the separate things that are touching, you can’t lose site of the trees because of the forest either. — Fire Ologist

Again, that evades the question by using language to convey the demarcation to the device.It could do that with AI directed actuation. Just tell the AI what you want to shoot — frank

The poster doesn't burst into flames. It ignites only where the gun is pointed, and spreads from there. So the gun hasn't defined any definition of demarcation, the metal frame has.You've just designed a gun that emits a destructive heat ray. Your IC board supports three settings for the temperature of the emitted heat ray. In order to test your settings, you turn a dial to the middle setting. This setting maxes out at the combustion threshold for common notebook paper. Pointing your gun, you fire at a notebook paper poster framed within the boundary of an iron rectangle. Will your gun make a discrimination, thus destroying only the paper? Success! The poster bursts into flame, burns up to gossamer black carbon and stops at the edge of the iron frame. — ucarr

Glad you're reaching for real examples though. They're hard to find outside of fiction. -

frank

19kIt could do that with AI directed actuation. Just tell the AI what you want to shoot

frank

19kIt could do that with AI directed actuation. Just tell the AI what you want to shoot

— frank

Again, that evades the question by using language to convey the demarcation to the device. — noAxioms

Still, an inanimate object can make distinctions you program it to recognize. You don't have to be a magic human to do that. I think the rest is just a matter of purpose. The phaser doesn't have any motives that aren't given to it. -

Apustimelogist

946Strange. We seem to in principle put labels around things any way we want, nevertheless there seems to be directly apparent underlying distinctions that we experience regardless of those labels (Arguably - at least that is my strong inclination - but I think there can be intractable debate about this that I am not sure about: e.g. overflow of consciousness and phenomenal/access distinction which I think is probably somewhat illusory).

Apustimelogist

946Strange. We seem to in principle put labels around things any way we want, nevertheless there seems to be directly apparent underlying distinctions that we experience regardless of those labels (Arguably - at least that is my strong inclination - but I think there can be intractable debate about this that I am not sure about: e.g. overflow of consciousness and phenomenal/access distinction which I think is probably somewhat illusory).

Those underlying distinctions also obviously depend on the way our brains happen to interact with the world - e.g. animals with different sense capabilities, the resolution we interact with world where solid objects are obviously constructed from something more fundamental - what seems like a "natural" object depends on the perspective. Even so, underneath we assume there are kinds of regularities in the world which, though we perceive and perhaps abstract through our limited perspectives, seem to capture objective distinctions out in the world beyond labels... distinctions we could never access mind-independently... what does a distinction even mean? How do you cash out the term "objective"? There is almost a paradox that clearly in principle there is some objective world, events, "things" not the same as other "things", changes in one place different from another place. But any labelling brings the arbitrarineas back.

Is object just not a coherent concept? One must just accept the limit that the mind constructs things in an arbitrary way about something which is "objective". Inherent contextual paradox. We can refer to an objective world but not without subjective machinery... but then how is that objective. Cannot be reconciled ever. No matter how you construe it, a reference, a label is an arbitrary label. This like an inherent glitch of epistemic perspectives. Maybe you can justify a label if it could not have been otherwise though. But we don't know enough. And even then you cannot say that other labels are invalid. The difference then is parsimony.

Fundamental object? But are there any in the universe? Is the universe a constant arrangement of little fundamental objects? Virtual particles emerge from the "aether". Elementary particles decay. Matter can be turned to energy and vice versa. Particles can change properties but I don't know how that works... once there was three weak bosons and hypercharge.. symmetry breaking, now there are two W, one Z boson and a photon. I also find it interesting that the discretization of fields into individual particle quanta seems in these models almost a side effect. It comes from boundary conditions which are the same reason anything else is quantized in quamtum mechanics. Only, a lot of things happen not to be quantized because they happen to not have those conditions. But do we really know what a field is? Seems quite abstract. Particles are then just due to energy levels of the field. What is energy even? Not even really a thing is it. Very abstract way of describing constraints on behavior. Literally everything in physics is about behavior, spatio-temporal transformations. Forces are about behavior involving symmetries. Particles representations of poincare symmetry groups. When you get down to it energy is the indicative of symmetry too... just perhaps the most fundamental one. There are no objects in physics in some sense... abstract functional behaviors... what even is mass but a resistence to force in some sense?

Do we need intrinsic fundamental objects in physics. What role would intrinsicness play? Would be almost epiphenomenal, homogenously indistinct... either that or inaccessible. Then when you try to imagine what the inaccessible would be like, you must still use labels, which ofcourse I have been using all along. Paradox I say. Because how can the world have no intrinsic nature... but again, "intrinsic nature" is an abstract concept we invent. Maybe just no possoble coherent access and so the paradox remains.

Maybe then you can identify distinct particles but they ephemeral and perhaps not fully well-defined scientifically (e.g. spatially). But again, label issue still there and deeper inaccessibility being beyond scientific model of observable behavior. Paradox. Can you define object in some other way? In terms of causal interactions and modal counterfactuals? Then again, causality is a construct and modality suffers same anti-realist arguments as any other scientific concept imo. -

Fire Ologist

1.7kWe lost sight of the twig because of the tree. How is that different? — noAxioms

Fire Ologist

1.7kWe lost sight of the twig because of the tree. How is that different? — noAxioms

No you didn’t. You said “twig” and then said “tree” and then noticed how they were “touching” which still sets out two separate objects in order for “touch” to make any sense either. THEN one can look closer at the two things touching and learn they are so connected they might be one thing, in which case you are just back to the same starting point where you said “twig” or carved out and identified one thing.

The process didn’t eliminate difference and identity, it just shows how it can be harder or easier to observe and delineate. -

NotAristotle

587Why is that the answer? Why is it easy that the other answers are wrong? What if the twig was the intent? — noAxioms

NotAristotle

587Why is that the answer? Why is it easy that the other answers are wrong? What if the twig was the intent? — noAxioms

It doesn't matter what the intent is, it matters what object has objectively been contacted by Midas' hand.

How did Midas not touch the forest? — noAxioms

I thought you said Midas touched a twig, not a forest. Why do you think the entire forest becomes golden? By this logic, wouldn't literally everything on Earth become golden when a twig is touched. I don't understand your reasoning here. -

fdrake

7.2kDid they have feet? — noAxioms

fdrake

7.2kDid they have feet? — noAxioms

Yes. Dinosaurs had feet. They're in the fossils. You can see the bones. You can see footprints.

Sort of. The momentum transfer there is almost the same whether the truck is empty, or loaded with double its unladen mass. — noAxioms

Yes. Almost the same. But not quite. Sum of masses blah blah.

Yes. There's purpose to that activity, making it normative. — noAxioms

Aye. One of those truck objects is normatively demarcated, one isn't. There's still underlying properties that need to be in place and individuated for both to make sense - like mass and spatial extent of the relevant particulars/placeholder terms. Like it really does behave like an object which is heavier for the collision, and it really does behave like a truck with another object inside of it for the unloading.

What I mean with the latter is that normative doesn't directly imply relative, 'cos it can be true that the truck was unloaded. You see what I mean? -

ucarr

1.9kThe poster doesn't burst into flames. It ignites only where the gun is pointed, and spreads from there. So the gun hasn't defined any definition of demarcation, the metal frame has. — noAxioms

ucarr

1.9kThe poster doesn't burst into flames. It ignites only where the gun is pointed, and spreads from there. So the gun hasn't defined any definition of demarcation, the metal frame has. — noAxioms

If we work backwards one causal step: "where the gun is pointed," how do we know the gun doesn't know the combustion differential between the paper and its iron border amounts to a stop? I ask this assuming we can reverse-engineer from outcomes to intentions. We see a gun pointed at a target made of multiple parts. How do we know the gun doesn't know what we know about combustion differentials? We see a gun pointed at a target. We don't know the scope of its intended destruction of the target until we see it. -

javi2541997

7.2kI thought you said Midas touched a twig, not a forest. Why do you think the entire forest becomes golden? By this logic, wouldn't literally everything on Earth become golden when a twig is touched. I don't understand your reasoning here. — NotAristotle

javi2541997

7.2kI thought you said Midas touched a twig, not a forest. Why do you think the entire forest becomes golden? By this logic, wouldn't literally everything on Earth become golden when a twig is touched. I don't understand your reasoning here. — NotAristotle

At first, I thought the same thing. According to his (@noAxioms) theory, everything would turn to gold with Midas' single touch. But I believe the essential point is that it only impacts things that are connected to one another. The twig, the tree, and finally the forest turn golden because they are all interdependent. However, Midas' touch will eventually lose its effectiveness. For example, consider the Sahara Desert and Antarctica. There are no woodlands there. The twig was the intended object, and the forest got golden on purpose because they are interdependent. Midas cannot turn Antarctica into gold with a single twig.

For this reason, I personally believe there is the possibility to stop the forest from becoming golden. If I chop the twig with the axe or rip out the roots, the process ends. Well, if I remove one element of the set, the magic of Midas is over. -

Wayfarer

26.1kThere's no no reason to draw a line where 'foot' is no longer applicable and 'rest of leg' comes into play. That's a complex model of a body with distinct parts all hooked together, and the dinos probably didn't work with such needlessly complex models. Maybe I'm wrong about this. — noAxioms

Wayfarer

26.1kThere's no no reason to draw a line where 'foot' is no longer applicable and 'rest of leg' comes into play. That's a complex model of a body with distinct parts all hooked together, and the dinos probably didn't work with such needlessly complex models. Maybe I'm wrong about this. — noAxioms

One of the main points of Pinter's book is the way cognition works is by carving out gestalts. A gestalt is a meaningful whole - basically, an object, but an object as perceived by a cognising subject, which distinguishes the object from its sorroundings and sees it as a unit. (The 'cognising subject' is not necessarily a human - this is something found in the cognition of even very simple animals, including insects - he gives the example of a fairy-fly, so small as to be impercetible to the naked eye.) These gestalts are the currency of structured cognition - along with every other sentient organism, we see the world in gestalts, in conjunction with the accompanying sensory and somatic inputs that enable us to navigate the world. In this context the mind has an active role in 'constructing' gestalts. That's what I think you're driving at. For us, there is clearly a reason to draw the line between 'foot' and 'leg' as we instinctively understand anatomy (which probably goes a long way back before knowledge of medical anatomy, to the carving up of prey animals with stone tools not to mention knowledge of your own and others’ bodies). So - I think you're on the right track.

The arche fossil is very much targeted against combining embodiment and materiality with reciprocal co-constitution. You can even read it as a constructive dilemma - reciprocal co constitution implies idealism about what is interacted with, or what is interacted with has independent properties, choose. — fdrake

Reciprocal co-constitution is the idea that human cognition and the material world mutually shape and define each other - that our understanding of the material world is inseparable from the cognitive frameworks we use to interpret it. But if in positing that, cognition is treated as an object or factor, alongside it's object, then that implies adopting a perspective outside of it, from which both cognition and its object can be contemplated. But how can that be done? This is why citing dinosaurs as an example of phenomena that pre-existed h.sapiens, and necessarily existing independently of the mind, misrepresents what it's seeking to criticize. Anything that pre-exists h.sapiens could be cited, as it is an empirical fact that h. sapiens evolved a finite period of time in the past (and relatively recently in geological time-scales). This criticism is not too far removed from Johnson's argument against Berkeley, the 'argumentum ad lapidem'. The idealist (or perhaps I should say the cognitivist) view is that the entire constellation of ideas and facts that are drawn upon to cite the fossil evidence, exist in a cognitive framework, which we bring to the picture. Whatever is 'outside' that cannot, as a matter of definiton, be cited or even referred to.

Dan Zahavi, a phenomenologist with whom I've become acquainted through philosophyforum, put it like this:

Ultimately, what we call “reality” is so deeply suffused with mind- and language-dependent structures that it is altogether impossible to make a neat distinction between those parts of our beliefs that reflect the world “in itself” and those parts of our beliefs that simply express “our conceptual contribution.” The very idea that our cognition should be nothing but a re-presentation of something mind-independent consequently has to be abandoned.

(From Husserl’s Legacy: Phenomenology, Metaphysics, and Transcendental Philosophy.) -

noAxioms

1.7k

noAxioms

1.7k

But I suspect that nothing 100 million years ago envisioned a foot as a distinct object. That was the point of my comment. Maybe I don't give the being of that age enough credit. It's all just either 'me', 'not me', or perhaps bulk goods.A gestalt is a meaningful whole - basically, an object, but an object as perceived by a cognising subject, which distinguishes the object from its sorroundings and sees it as a unit. — Wayfarer

Question is, it is anything more than a concept? Nobody is suggesting that as a concept, it is incoherent. Well, mostly nobody.Is object just not a coherent concept? — Apustimelogist

Then you've communicated the convention to it. The question is if 'object' is defined in the absence of that communication.Still, an inanimate object can make distinctions you program it to recognize — frank

Are the motives given to the beam itself? Because the phaser doesn't pick what disappears, the beam does. It also doesn't shoot past the thing it just disintegrated, a strange side effect for something that emits a beam for a full half second or so.The phaser doesn't have any motives that aren't given to it. — frank

THEN one can look closer at the two things touching and learn they are so connected they might be one thing — Fire Ologist

But everything is connected, or nothing is. I mean, everything interacts via fields of force (as jkop put it). What is a connection if not that?But I believe the essential point is that it only impacts things that are connected to one another. — javi2541997

Not just Earth. So the logic (from 'twig' to 'tree') doesn't work.I thought you said Midas touched a twig, not a forest. Why do you think the entire forest becomes golden? By this logic, wouldn't literally everything on Earth become golden when a twig is touched. — NotAristotle

Because the gun 'knowing' anything violates the OP.how do we know the gun doesn't know ... — ucarr -

javi2541997

7.2kBut everything is connected, or nothing is. I mean, everything interacts via fields of force (as jkop put it). What is a connection if not that? — noAxioms

javi2541997

7.2kBut everything is connected, or nothing is. I mean, everything interacts via fields of force (as jkop put it). What is a connection if not that? — noAxioms

I agree. What I'm trying to say is that the interaction is dependent on a collection of 'things' or 'objects'. Your example began with a twig and continues as follows: a twig + the tree + the forest. These three elements combine to form a common set. If Midas touches one of the elements, the set turns gold. However, because 'everything' is connected, we may believe that the ground and then the earth will become golden as well. I disagree with the latter. I don't get how if Midas transforms a forest into gold, the Sahara Desert becomes linked to the same chain. There are no trees in the desert, thus I don't understand how it is dependant on the first set of twig + tree + forest.

Everything is not necessarily connected. -

Fire Ologist

1.7kBut everything is connected, or nothing is. — noAxioms

Fire Ologist

1.7kBut everything is connected, or nothing is. — noAxioms

In order for everything to be connected, you have to have separate things that connect. So saying everything is connected, is saying everything is separate as well. Otherwise you are saying all is one thing and nothing else.

My liver is connected to my brain but my liver is separated from my brain. Maybe we have to keep moving the lines as we define the point where these separate things connect, but we don’t need to see that my liver is my brain. -

Count Timothy von Icarus

4.3k

Count Timothy von Icarus

4.3k

But that's an answer isn't it?

Certainly. Like I said, multiplicity is given in experience, and this doesn't seem to be arbitrary. Yet you're not going to get canonical dividing lines between objects in physics. This jives well with classical arguments for the necessary "unity of being," (Unum as one of the Transcedentals). If you had a "second sort of being" that didn't interact with our sort (even mediately), it would be epistemologically inaccessible and, by definition, its existence or non-existence could never make any difference for us. All being then, or at least all being that isn't a completely inaccessible bare posit, shares in a sort of unity where everything interacts with everything else (even if this interaction is mediated in some cases).

But we could consider that an AI or machine could distinguish things based on form. A machine charged with eliminating White Snake's "Lonely Road," could identify it in disparate media: on magnetic tapes, in sound waves, encoded on hard drives or compact discs, or even encoded in in neurons. That is, we can define things in terms of substrate independent relationships (information). Yet a machine could obviously also distinguish between a magnetic tape and a sound wave by other means.

Form, at least form as information, seems to be definable in complete mathematical abstraction, but there are still problems with it. If we change one note in White Snake's song is it the same. What about covers? What happens if we keep losing fidelity until it becomes indistinguishable from many other possible recordings?

So on the formal side there is an inherit instability and ambiguity too, precisely because form can be so precisely defined that minute changes constitute new mathematical entities. Thus, we might want to allow for such ambiguities and variance in form by looking at key morphisms that would allow for a mapping across similar entities. But which morphisms matter? Again, the mind and its relation to the object seems essential for defining this.

This back and forth instability reminds me of the sort of things both Hegel and Pryzwara like to deal in. I do think Hegel's doctrines of essence and concept represent a good answer here, but they are a bit much to get into. Ultimately, concepts are determined by what a thing is, but what a thing is includes its relation to Geist/mind. Concept and delineation evolution aren't arbitrary but evolve as part of what things are (which includes how they are known) .

I don't think so. There's no physical evidence behind the way we divide the world up.

None at all? It seems there is plenty of physical evidence behind the distinction between plant and animal, living and non-living, physical squares and physical triangles, etc. The problem is, to my mind, not lack of physical evidence for our distinctions but rather the desire to want to define the objects of knowledge without reference to the knower or that knowledge's own coming into being. It's the problem of presupposing a certain sort of atomism.

Well, this is the old problem of The One and the Many, no? Being has to be a unity of sorts, but there has to be some way to affirm multiplicity or else we end up like Parmenides, unable to affirm anything, only able to speak the all encompassing Eastern "ohm." But everything can't be completely discrete or arbitrary either, or else we also can't say anything about anything.

I do think the univocity of being makes this problem particularly acute, which is why Plato's original solution has a sort of vertical dimension to reality. -

frank

19kNone at all? It seems there is plenty of physical evidence behind the distinction between plant and animal, living and non-living, physical squares and physical triangles, etc. — Count Timothy von Icarus

frank

19kNone at all? It seems there is plenty of physical evidence behind the distinction between plant and animal, living and non-living, physical squares and physical triangles, etc. — Count Timothy von Icarus

You're talking about universals, there, so you're starting with a time-honored way of dividing things up. I was talking about particulars. For particulars, it's like this:

-

noAxioms

1.7k

noAxioms

1.7k

Indirectly. The comment talked about even bugs having gestalts, but a bug has no pragmatic use for a concept of a foot.And didn't my comment elaborate on that very idea? — Wayfarer

All kind of off topic, since I am looking for an 'object' that is independent of a gestalt, even if discussion of it necessarily isn't.

Doesn't stop with Earth either.If Midas touches one of the elements, the set turns gold. However, because 'everything' is connected, we may believe that the ground and then the earth will become golden as well. I disagree with the latter. — javi2541997

So what changes along the way? In the absence of semiotics, why demarks the border between what turns to gold and what doesn't? It isn't being 'connected' because there's no border to that. If that was the definition, the universe would contain exactly one object, rendering the term essentially meaningless.

I don't understand how it got from twig to tree. The word 'connected' was floated around, but no finite physical definition of that was supplied. If it means particles that interact by fields of force, then the twig is connected to the desert because there's force between the two subsets. There's no finite limit to that.There are no trees in the desert, thus I don't understand how it is dependant on the first set of twig + tree + forest.

Several people made similar comments. The concept of 'twig is part of a tree, but not part of a continent' is pretty intuitive for a human, but when you take away the human convention, it's not so easy to pin down.

Then come up with a definition of 'connected' that doesn't make everything into one connected thing.Everything is not necessarily connected. — javi2541997

Or there is but one thing. By the only definition of 'connected' I've seen, it implies one universal object, one that Midas cannot avoid touching.In order for everything to be connected, you have to have separate things that connect. — Fire Ologist

So come up with a better definition of 'thing' that still doesn't involve human convention. How is a device, to which the convention has not been communicated, able to perform its function on the object indicated, and not on just a part of it, or on more than what was indicated.Otherwise you are saying all is one thing and nothing else.

By what definition is this true? Sure, by language, 'liver' and 'brain' demark a region of certain biological life forms. But in the absence of that language, is 'this' the same thing as 'that'? Perhaps this and that are the same life form. Perhaps this and that each refer to only a cell wall and not an organ or organism at all. Only with language/semiotics does it become demarked, which is what this topic asserts.My liver is connected to my brain but my liver is separated from my brain.

I say 'semiotics' because it isn't just language. A seagull might pick out the eyes of some fresh dead thing it finds. It doesn't have words for that, but it knows that eyes are the best part.

You don't think so what? My comment that you quoted was a reply to your suggestion of communicating the convention to the device, and then you say "I don't think so", which makes it sound like either programming the device isn't a form of communication, or maybe denying your earlier suggestion of making the device 'smart'.I don't think so. — frank

I pretty much said that in my OP, yes.There's no physical evidence behind the way we divide the world up.

The sci-fi examples or the Midas Touch I think are unanswerable. — Count Timothy von IcarusBut that's an answer isn't it? — noAxioms

Of course. A machine has access to the same conventions and language as biological things. An AI would often be able to utilize the appropriate convention if there is language involved, but there still isn't language involved in shooting a gun, so it must rely on typical conventions and guesswork. Worse, it isn't the gun that needs to decide, but rather the energy beam that it shoots that needs to figure this stuff out.Certainly.

...

But we could consider that an AI or machine could distinguish things based on form. — Count Timothy von Icarus

Sounds like somebody communicated with it, demarking the boundaries, however arduous the task might be.A machine charged with eliminating White Snake's "Lonely Road,"

Note too that you're treating data like an object, not a particular, but all patterns that meets a certain criteria. Your question then becomes, where it that line drawn between something that matches sufficiently and something that isn't. The boundaries are demarked, but not clearly, so judgment must be employed.

Same logic can be used with a gun: "Kill Bob", which can be interpreted as "eliminate the existence of the current state of Bob" which is effortless since Bob is continuously changing. So it becomes 'make a sufficiently significant change to Bob, which may leave a life form behind that no longer qualifies as Bob. -

Apustimelogist

946Question is, it is anything more than a concept? Nobody is suggesting that as a concept, it is incoherent. Well, mostly nobody. — noAxioms

Apustimelogist

946Question is, it is anything more than a concept? Nobody is suggesting that as a concept, it is incoherent. Well, mostly nobody. — noAxioms

But then surely the concept of an object as an objective thing would be incoherent? -

javi2541997

7.2kThen come up with a definition of 'connected' that doesn't make everything into one connected thing. — noAxioms

javi2541997

7.2kThen come up with a definition of 'connected' that doesn't make everything into one connected thing. — noAxioms

To be honest, I believe we are mixing up distinct notions here. 'Connected' means to be joined to something else. For example, when I connect the red wire to the red port or connect the electricity and water supply to my home. It appears (to me) that some elements are linked to one or two things at most, but not to everything.

While 'interdependent' (as I used in my argument) refers to groups that are dependent on one another. We may say that if every element is interdependent, then everything will turn gold with the touch of Midas. Nonetheless, I still disagree. There are some elements dependent upon one another (twig + branch + tree = forest. All these are a common and interdependent set) while others don't. I can't see how the air or the clouds could be golden too, according to your argument. -

ucarr

1.9k

ucarr

1.9k

how do we know the gun doesn't know ... — ucarr

Because the gun 'knowing' anything violates the OP. — noAxioms

I could only conclude that what constitutes an 'object' is entirely a matter of language/convention. There's no physical basis for it. I can talk about the blue gutter and that, by convention, identifies an object distinct from the red gutter despite them both being parts of a greater (not separated) pipe. — noAxioms

Is this the premise you're examining? -

Count Timothy von Icarus

4.3k

Count Timothy von Icarus

4.3k

Ha, that's a funny clip.

You're talking about universals, there, so you're starting with a time-honored way of dividing things up.

Aren't they two sides of the same coin? We have evidence to tell us that a plant is different from an animal (universal ). We also have plenty of empirical evidence to support the idea that this pumpkin right here is different from the one "over there on the shelf," namely their different, observable histories, variance in accidental properties, and obviously their appearing to be in two different spaces (concrete).

Likewise, there is plenty of physical evidence to support contentions like "this pumpkin here is the same pumpkin that was here last night." Yes, the pumpkin has changed overnight, so we might consider if it is really the same pumpkin, but nonetheless, we still have physical evidence that to help us distinguish what we mean by "this pumpkin that has been on the shelf all night." For instance, a video of the pumpkin sitting on the shelf all night is such physical evidence.

If there was absolutely no physical evidence to demarcate particulars then decisions about them would be completely arbitrarily, and it should random whether I consider my car today to be the same car I drove last month. But our consideration of particulars isn't arbitrary, nor do they vary wildly across cultures, even if they can't be neatly defined.

I think the problem here is the same problem I referenced before, wanting to try to define objects, delineation, continuity, etc. completely without reference to things' relationships with Mind ("Mind" in the global sense since this is where concept evolve). -

Manuel

4.4kI mostly agree. I would merely add that if we keep in mind that what we are constantly dealing with are mental constructions, this should not be surprising that a lot of what we interact with is a matter of convention.

Manuel

4.4kI mostly agree. I would merely add that if we keep in mind that what we are constantly dealing with are mental constructions, this should not be surprising that a lot of what we interact with is a matter of convention.

I would only quibble with the topic of a "physical basis". Does that mean a basis in physics? Well physics will tell you little about ordinary objects. Novelists and ordinary people may say more about these things.

If physical basis means something else, then I would like to know. Until someone can present a convincing argument as to what "physical" must contrast with (and why is this so) we may do away with "physical" and speak about "objective basis" of objects. -

frank

19kIf physical basis means something else, then I would like to know. Until someone can present a convincing argument as to what "physical" must contrast with (and why is this so) we may do away with "physical" and speak about "objective basis" of objects. — Manuel

frank

19kIf physical basis means something else, then I would like to know. Until someone can present a convincing argument as to what "physical" must contrast with (and why is this so) we may do away with "physical" and speak about "objective basis" of objects. — Manuel

The cultural background of this discussion is the image of God as a clockmaker, who sets the world in motion, then leaves it to itself. Subtract out the God, and you have a mechanistic universe, which is part of our present worldview. Things like universals, ideas, abstract objects, etc. become ill-fitting phantoms . They aren't addressed by physics because they don't count as real in the sense an atom is supposed to be. So this worldview says the real is physical. It's contrasted to unreal ideas.

This is why it can be startling to realize that when I look around, I'm seeing ideas. It's just Plato back again, right? -

frank

19kAren't they two sides of the same coin? We have evidence to tell us that a plant is different from an animal (universal ) — Count Timothy von Icarus

frank

19kAren't they two sides of the same coin? We have evidence to tell us that a plant is different from an animal (universal ) — Count Timothy von Icarus

There isn't a scientific definition of life according to Robert Rosen. If pressed to come up with one, we'd have to say it has something to do with a final cause, but this isn't something we find in the physical realm. Plants have chlorophyl, but so do euglenas, which aren't plants or animals. We can't say plants don't eat, because Venus flytraps do. It's fuzzy boundaries.

We also have plenty of empirical evidence to support the idea that this pumpkin right here is different from the one "over there on the shelf," namely their different, observable histories, variance in accidental properties, and obviously their appearing to be in two different spaces (concrete). — Count Timothy von Icarus

It's true that pumpkin distinctions seem to be the sort of thing we discover. I don't recall deciding to divide the pumpkin off from the rest of the world, for instance. The distinction is there whether I'm looking at it or not. But look again. Look at the visual field that includes the pumpkin. Feel of the pumpkin with your hand. Smell the pumpkin. Where in any of this data is pumpkin?

f there was absolutely no physical evidence to demarcate particulars then decisions about them would be completely arbitrarily, and it should random whether I consider my car today to be the same car I drove last month. But our consideration of particulars isn't arbitrary, nor do they vary wildly across cultures, even if they can't be neatly defined. — Count Timothy von Icarus

The object is a fusion of idea and matter. We can hardly reject physicality. It's definitely there. It's just that the way we divide up the universe is conventional. It could be divided up differently.

I think the problem here is the same problem I referenced before, wanting to try to define objects, delineation, continuity, etc. completely without reference to things' relationships with Mind ("Mind" in the global sense since this is where concept evolve). — Count Timothy von Icarus

I agree. If an object is a fusion of idea and matter, then subtracting out idea, gives us something we can't imagine. -

Manuel

4.4kyou have a mechanistic universe, which is part of our present worldview — frank

Manuel

4.4kyou have a mechanistic universe, which is part of our present worldview — frank

Yes. That is correct as a matter of intuition, or folk-psychology. It's built-in the way we interpret things.

Things like universals, ideas, abstract objects, etc. become ill-fitting phantoms . They aren't addressed by physics because they don't count as real in the sense an atom is supposed to be. So this worldview says the real is physical. It's contrasted to unreal ideas. — frank

Something like this seems to be the drive between such thinking. It's kind of curious then, when you consider what our most accurate physics says what an atom is, has nothing to do with the intuition that leads us to believe that atoms are these visible concrete things, that make the world up.

And atom is far from that, and perhaps should be considered more of a kind of "cloud" of activity, which is so far removed from anything we can visualize it starts to look like an idea of sort, which is NOT to say that the atom itself is an idea.

It's just Plato back again, right? — frank

Plato... I suppose it depends on how he is interpreted now. If the interpretation is that we have a single perfect idea of a horse or a tree, then that's too strict, imo. If he is interpreted more softly as ideas are the mediation through which we experience the world, that is better.

But yes, on the whole. -

Count Timothy von Icarus

4.3k

Count Timothy von Icarus

4.3k

There isn't a scientific definition of life according to Robert Rosen. If pressed to come up with one, we'd have to say it has something to do with a final cause, but this isn't something we find in the physical realm. Plants have chlorophyl, but so do euglenas, which aren't plants or animals. We can't say plants don't eat, because Venus flytraps do. It's fuzzy boundaries.

Right, there is not a perfect physical definition, but there is certainly physical evidence for such definitions. Conventions could be different. They sometimes are from place to place or time to time. But they only tend to differ so much, and they don't develop arbitrarily, but rather develop in line with sense evidence (physical evidence). Historically, things obviously help to develop the notions that they can be said to instantiate.

Things are defined by their relations, including their relationships to mind.

But look again. Look at the visual field that includes the pumpkin. Feel of the pumpkin with your hand. Smell the pumpkin. Where in any of this data is pumpkin?

It's in there. Otherwise, when kids point at things and ask "what is this?" we should have little idea what they are referring to, since it could be any arbitrary ensemble of sense data. But when a toddler points towards a pumpkin and asks what it is, you know they mean the pumpkin, not "half the pumpkin plus some random parts of the particular background it is set against."

Yet if there were no objects (pumpkins, etc.) given in sensation, kids should pretty much be asking about ensembles in their visual field at random, and language acquisition would be hopelessly complex. The woes of people with agnosia have been enough to convince me that a cognitive grasp of the intelligibility of objects is fundamental to perception. If we had to conciously abstract from and learn the visual ques that represent depth, for example, we'd have quite a time learning to walk.

Even animals recognize discrete wholes; the sheep knows "wolf" and knows it from the time it is a lamb. -

Count Timothy von Icarus

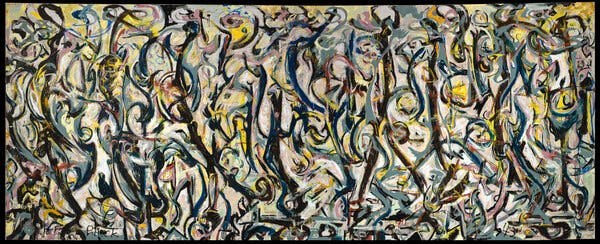

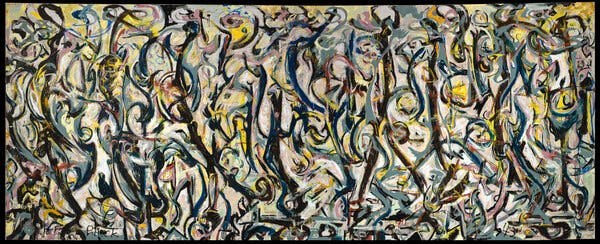

4.3kI also think this gets at why AI images full of unrecognizable images are generally taken as "creepy" or "disgusting."

Count Timothy von Icarus

4.3kI also think this gets at why AI images full of unrecognizable images are generally taken as "creepy" or "disgusting."

Whereas abstract art can be quite lovely:

-

Apustimelogist

946It's in there. Otherwise, when kids point at things and ask "what is this?" — Count Timothy von Icarus

Apustimelogist

946It's in there. Otherwise, when kids point at things and ask "what is this?" — Count Timothy von Icarus

But is this a child detecting objects or a child that is detecting statistics (which maybe has been honed over development too)? You then ask that doesn't detecting statistics depend on what kind of statistics you are sensitive too and where you find yourself in the world? A pumpkin looks very obviously like a single object to us but these statistical regularities that make up a pumpkin are decomposable because we know a pumpkin is made up of lots of different things inside which generally we are not aware of - many scales above and below. The child certainly isn't aware of atoms, forces etc. Is the child detecting an object? Or statistics.

You can train people to detect all sorts of statistics and things in the right context which they normally wouldn't consider significant in any other. I think another point is that I think our perception and language is sophisticated and flexible that it can detect any kind of objects it wants given the need. No one normally uses the concepts bleen or grue... but if we wanted to we obviously can. The indeterminacy is there all the time and we can use it but choose to restrict ourselves.

Here is one thing I am inclined to recently. Concepts aren't really a thing. Knowledge is not in words. We can have knowledge without words and use it very well. And once you take away the words its pretty vague the idea of drawing boundaries and labels around things because when we manipulate the world and predict things it transcends any fixed, coarse labels. My ability to use objects with my hands and maybe invent new ones, new uses has nothing to do with fixed boundaries I must respect. There is an extreme fluidity in how I enact my knowledge.

Words are just about communication. It is just something we use to help convey information. Words don't define the things in themselves and words don't even have rigid meanings beyond our ability to manipulate them.

There are no concepts just our interactions with the world through a neural space with incredible ability to distinguish through its many degrees of freedom. We can detect regularities. But that in itself is utilizing the same kind of space of degrees of freedom. There are an enormous numberways we can act, react, distinguish in ways which differ and overlap in regard to the things that show up in the cortical space. -

Wayfarer

26.1kThis is why it can be startling to realize that when I look around, I'm seeing ideas. It's just Plato back again, right? — frank

Wayfarer

26.1kThis is why it can be startling to realize that when I look around, I'm seeing ideas. It's just Plato back again, right? — frank

I've been puzzling over, and reading up on, the basic dictum of Plato's metaphysics, which is 'to be, is to be intelligible'. From what I've gleaned, it means that to grasp an object's intelligibility is to see what it really is. Perhaps that's why @Count Timothy von Icarus's non-objects are intuitively felt to be 'creepy and disgusting'.

Even animals recognize discrete wholes; the sheep knows "wolf" and knows it from the time it is a lamb. — Count Timothy von Icarus

Hence the 'gestalts' in this post.

Welcome to The Philosophy Forum!

Get involved in philosophical discussions about knowledge, truth, language, consciousness, science, politics, religion, logic and mathematics, art, history, and lots more. No ads, no clutter, and very little agreement — just fascinating conversations.

Categories

- Guest category

- Phil. Writing Challenge - June 2025

- The Lounge

- General Philosophy

- Metaphysics & Epistemology

- Philosophy of Mind

- Ethics

- Political Philosophy

- Philosophy of Art

- Logic & Philosophy of Mathematics

- Philosophy of Religion

- Philosophy of Science

- Philosophy of Language

- Interesting Stuff

- Politics and Current Affairs

- Humanities and Social Sciences

- Science and Technology

- Non-English Discussion

- German Discussion

- Spanish Discussion

- Learning Centre

- Resources

- Books and Papers

- Reading groups

- Questions

- Guest Speakers

- David Pearce

- Massimo Pigliucci

- Debates

- Debate Proposals

- Debate Discussion

- Feedback

- Article submissions

- About TPF

- Help

More Discussions

- Artificial Super intelligence will destroy every thing good in life and that is a good thing.

- Do physical models give a good view in the physical reality?

- Can you imagine a different physical property that is doesn't exist in our current physical universe

- For Kant, does the thing-in-itself represent the limit or the boundary of human knowledge?

- Other sites we like

- Social media

- Terms of Service

- Sign In

- Created with PlushForums

- © 2026 The Philosophy Forum