-

Wayfarer

26.2kJust wondering’, you know, given my philosophical proclivities….what kind of answer can one expect when asking about the status of reason? — Mww

Wayfarer

26.2kJust wondering’, you know, given my philosophical proclivities….what kind of answer can one expect when asking about the status of reason? — Mww

I’m vary wary of any attempt to *explain* reason. It seems obvious to most that ‘it evolved’, as above, but I see that as reductionist, in that it reduces reason to a matter of adaptation. That’s why I frequently refer to Thomas Nagel’s essay Evolutionary Naturalism and the Fear of Religion, which is also a defence of the ‘sovereignty of reason’ against naturalistic accounts. -

Wayfarer

26.2kYes, and also, don't believe everything you read on the Internet.

Wayfarer

26.2kYes, and also, don't believe everything you read on the Internet.

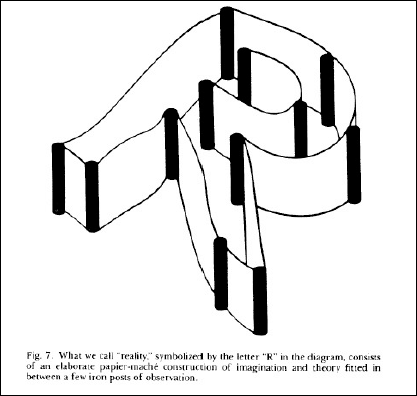

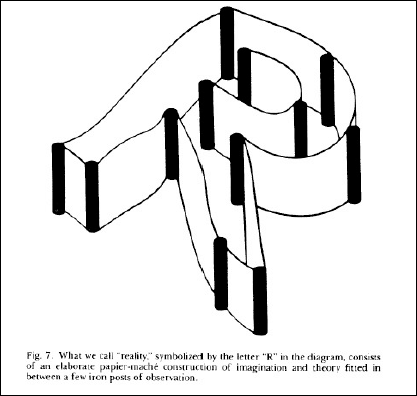

More germane to the actual argument, another graphic I posted previously, from John Wheeler's Law Without Law:

-

Janus

18kWheeler's diagram suggests that nature can be carved up in any number of ways. A good mathematician (which I'm not) would be able to tell you how many different ways the poles could be joined, each giving a different configuration. What do you think the analogy means?

Janus

18kWheeler's diagram suggests that nature can be carved up in any number of ways. A good mathematician (which I'm not) would be able to tell you how many different ways the poles could be joined, each giving a different configuration. What do you think the analogy means?

I'm curious as to who and what you're addressing here. -

Wayfarer

26.2kWhat do you think the analogy means? — Janus

Wayfarer

26.2kWhat do you think the analogy means? — Janus

It is in a rather curious essay called Law Without Law which you can find here https://m.psychonautwiki.org/w/images/3/30/Wheeler_law_without_law.pdf

Wheeler is well-known for his idea of the participatory universe, that the universe is somehow brought into being by the act of observation (although his definition of ‘observation’ is rather broad as shown below). There’s a well-written magazine article on him here, from which:

While conscious observers certainly partake in the creation of the participatory universe envisioned by Wheeler, they are not the only, or even primary, way by which quantum potentials become real. Ordinary matter and radiation play the dominant roles. Wheeler likes to use the example of a high-energy particle released by a radioactive element like radium in Earth's crust. The particle, as with the photons in the two-slit experiment, exists in many possible states at once, traveling in every possible direction, not quite real and solid until it interacts with something, say a piece of mica in Earth's crust. When that happens, one of those many different probable outcomes becomes real. In this case the mica, not a conscious being, is the object that transforms what might happen into what does happen. The trail of disrupted atoms left in the mica by the high-energy particle becomes part of the real world.

At every moment, in Wheeler's view, the entire universe is filled with such events, where the possible outcomes of countless interactions become real, where the infinite variety inherent in quantum mechanics manifests as a physical cosmos. And we see only a tiny portion of that cosmos. Wheeler suspects that most of the universe consists of huge clouds of uncertainty that have not yet interacted either with a conscious observer or even with some lump of inanimate matter. He sees the universe as a vast arena containing realms where the past is not yet fixed.

I certainly don’t claim to understand everything about it, but it’s interesting, and also very much the kind of science that the OP was about (as I point out in my earlier post.) -

fdrake

7.2kWheeler is well-known for his idea of the participatory universe, that the universe is somehow brought into being by the act of observation (although his definition of ‘observation’ is rather broad as shown below). There’s a well-written magazine article on him here, from which: — Wayfarer

fdrake

7.2kWheeler is well-known for his idea of the participatory universe, that the universe is somehow brought into being by the act of observation (although his definition of ‘observation’ is rather broad as shown below). There’s a well-written magazine article on him here, from which: — Wayfarer

We cannot speak in these terms without a caution and a question. The caution: "consciousness" has nothing whatsoever to do with the quantum process. — Wheeler -

Count Timothy von Icarus

4.3k

Count Timothy von Icarus

4.3k

Sure, but so is "if mind creates nature..."

If mind (and rationality) is completely sui generis, then I'm not sure why solipsism and radical skepticism about any external world wouldn't be justified. Our entire epistemological toolkit could only be said to apply to mind. And really, it would only apply to our own particular mind, as we'd have no reason to think all minds shape reality the same way. Any "noumena" is forever beyond us, and we might as well be locked in our own separate worlds, as Locke feared.

This problem plays out with the Kant - Fichte/Hegel divide, but it interestingly seems to show up in the mind of Augustine 1,600 years earlier. Augustine famously invokes what is essentially Descartes "cognito ergo sum," for dealing with radical skeptics, but he still has Locke's concerns about everyone being "locked in" to their own world by the senses. His bridge back to a unified world is the universal Logos through which things are known, in the dialectical phenomenology of "De Trinitate." What I find interesting here is that, down to the dialectical/phenomenological style, this is in a lot of ways similar to Hegel's version of the "transcendental deduction to repair the dualism problem. Both attempts are far from clear, but I think they're right to start from the essential aspects of experience.

Yes, and also, don't believe everything you read on the Internet.

Yeah, apparently they had done a lot to fix Chat GPT's famous problems with primes. Interestingly though, since it is sort of a black box, they got it to do a lot better on those questions for awhile, and apparently new tweaks have led to it failing them more often again. It's not meant to be a mathbot, so I don't really hold it against it.

I've seen it first hand with code. It's remarkably good at writing code in common languages like Java. If you ask it to use proprietary languages like DAX, it is less reliable. I asked it to use the quite rare logical language of Prolog as a test and it spat out convincing looking gibberish.

But that makes sense. It's only going to be as good as its inputs. -

Metaphysician Undercover

14.9kWheeler suspects that most of the universe consists of huge clouds of uncertainty that have not yet interacted either with a conscious observer or even with some lump of inanimate matter. He sees the universe as a vast arena containing realms where the past is not yet fixed.

Metaphysician Undercover

14.9kWheeler suspects that most of the universe consists of huge clouds of uncertainty that have not yet interacted either with a conscious observer or even with some lump of inanimate matter. He sees the universe as a vast arena containing realms where the past is not yet fixed.

I wonder what a cloud of uncertainty looks like. There's something essential missing from this perspective. What is the case, is that we do not in any way actually observe the "cloud" of uncertainty, or possibility, it is detected by logic, and not seen or sensed at all. What is observed is the posterior, the physical universe after those interactions which are referred to.

So, we do not observe the cloud of uncertainty, yet we do observe what is known as "interactions". And whatever it is that happens, which brings something to be from the cloud of possibilities, this, as an actual cause, cannot be an observable "interaction". But as a cause it is prior in time to the observable interactions of the physical universe, and it must itself be an "action".

This implies that there must be something actual, an actual cause, existing within that cloud of uncertainty, which is unobservable. As an actual cause though, it must also be intelligible. Recognition of this intelligible actuality, inherent within the cloud of uncertainty, as the cause of the particular event which is observable, is the essential aspect which is missing from that perspective. We must recognize that the cause of something observable, the cause of observability, is itself necessarily prior to the act of observation. This frees us from the illogical assumption that the posterior act of observation could be the cause of what is observable, also rendering the cloud of uncertainty or possibility, as inherently intelligible, in relation to the observable physical universe. -

Wayfarer

26.2kIf mind (and rationality) is completely sui generis, then I'm not sure why solipsism and radical skepticism about any external world wouldn't be justified. — Count Timothy von Icarus

Wayfarer

26.2kIf mind (and rationality) is completely sui generis, then I'm not sure why solipsism and radical skepticism about any external world wouldn't be justified. — Count Timothy von Icarus

I'll go back to this point:

If the mind creates the world, did the Moon exist before minds?

— Count Timothy von Icarus

Definitely not. But neither did it not exist. — Wayfarer

You didn't respond to this point, but it is the crux of the matter.

You will remember that Einstein asked, ironically, 'doesn't the moon continue to exist if we're not watching it?' (which I presume you're referring to). He was doubtless pondering the sense in which the act of measurement seems to bring about (or manifest) a material outcome in quantum physics. He was adamantly of the view that what is to be measured must exist anyway, regardless of it having been measured or not. That was the crux of his dispute with Neils Bohr over his many years of debates (as described in Manjit Kumar 'Quantum'.) I take Einstein's view to represent scientific realism.

Whereas I have the understanding that the answer to the question, 'does the electron exist prior to the act of measuring it?' just is the wave equation. And that equation provides degrees of likelihood for the subject's location across a range of probabilities. It doesn't unambiguously provide a yes/no answer to the question 'does it exist?' I think this is the origin of Einstein's discomfort with quantum physics.

I think the implications are philosophically very interesting, because it introduces the concept of there being degrees of reality. The kind of existence the electron has is not definite, but it is governed by probabalistic laws. Werner Heisenberg said in Physics and Philosophy 'It introduced something standing in the middle between the idea of an event and the actual event, a strange kind of physical reality just in the middle between possibility and reality.' Heisenberg compares this to Aristotle's 'potentia', which I think can be paraphrased as 'the real realm of possibility'.

It has been experimentally demonstrated that measurements on entangled particles, such as photons, display an inexplicable correlation. You can set up an experiment so that before a measurement is made, either photon could be spinning clockwise or counterclockwise. Once one is measured, though (and found to be, say, clockwise), you know the other will have the opposite spin (counterclockwise), no matter how far away it is. But no secret signal is (or could possibly be) sent from one photon to the other after the first measurement. But drawing on Heisenberg's 'potentia' concept, it’s simply the case that "counterclockwise" is no longer on the list of res potentia for the second photon. An “actuality” (the first measurement) changes the list of potentia that still exist in the universe. Potentia encompass the list of things that may become actual; what becomes actual then changes what’s on the list of potentia. (This is the 'transactional' interpretation of QM.)

Generally speaking, observations of any quantum state, containing many possibilities, turns one of those possibilities into an actual one. And the new actual event constrains the list of future possibilities, without any need for physical causation. “We simply allow that actual events can instantaneously and acausally affect what is next possible … which, in turn, influences what can next become actual, and so on."

Measurement, then, is a real physical process that transforms (or manifests) quantum potentia into actual, real stuff in the ordinary sense. Space and time, or spacetime, is something that “emerges from a quantum substratum,” as actual reality that manifests from "the realm of possibles.” Spacetime, therefore, is not all there is to reality (Quantum mysteries dissolve if possibilities are realities).

There is more to be said but that's enough for one post. -

RogueAI

3.5kI'll go back to this point:

RogueAI

3.5kI'll go back to this point:

If the mind creates the world, did the Moon exist before minds?

— Count Timothy von Icarus

Definitely not. But neither did it not exist.

— Wayfarer — Wayfarer

I don't get this. If all minds disappeared right now, either the moon would continue to exist or cease to exist. There's no middle ground between existing and not existing. -

jgill

4kThere's no middle ground between existing and not existing. — RogueAI

jgill

4kThere's no middle ground between existing and not existing. — RogueAI

There's the problem, whether regarding the moon or a quantum particle. Were philosophical terms defined more clearly some threads would vanish. Exist physically, or exist metaphysically? One or the other or both or neither? Then there are those damned probability waves, always collapsing like snowcones on a summer day just because we stare at them.

The moon shows a tendency to persist when we look away. -

Wayfarer

26.2kPhilosophy, of all subjects, is concerned with the meaning of existence. It is often commented that in the preamble to Aristotle's Metaphysics he mentions the difficulties presented by the different meanings of the verb 'to be'. '‘being’, as Aristotle tells us in Γ.2, is “said in many ways”. That is, the verb ‘to be’ (einai) has different senses, as do its cognates ‘being’ (on) and ‘entities’ (onta). So the universal science of being qua being appears to founder on an equivocation: how can there be a single science of being when the very term ‘being’ is ambiguous?'(SEP)

Wayfarer

26.2kPhilosophy, of all subjects, is concerned with the meaning of existence. It is often commented that in the preamble to Aristotle's Metaphysics he mentions the difficulties presented by the different meanings of the verb 'to be'. '‘being’, as Aristotle tells us in Γ.2, is “said in many ways”. That is, the verb ‘to be’ (einai) has different senses, as do its cognates ‘being’ (on) and ‘entities’ (onta). So the universal science of being qua being appears to founder on an equivocation: how can there be a single science of being when the very term ‘being’ is ambiguous?'(SEP)

There seems to be a casual assumption that 'everyone knows' what it means for something to exist. After all you can open your eyes and see it. But again philosophy is exploring that question from a critical - not necessarily outright sceptical - perspective. -

Janus

18kWhat does it mean to say that possibilities are realities? Does it just mean that some possibilities are real, as opposed to merely logical? Unless it means something more than that it is certainly not a novel idea. — Janus

Janus

18kWhat does it mean to say that possibilities are realities? Does it just mean that some possibilities are real, as opposed to merely logical? Unless it means something more than that it is certainly not a novel idea. — Janus

Suggest you read the Science News article. They note the idea goes back to Aristotle, but I think it is one of the things that fell out of favour with the abandonment of Aristotelian realism. — Wayfarer

I did read the article. You haven't answered the question as to whether you think the claim that possibilities are realities means something beyond what I believe is commonly accepted: namely that there are real possibilities and merely logical possibilities.

If that idea has not "fallen out of favour" then what exactly is the idea that you think has fallen out of favour?

There seems to be a casual assumption that 'everyone knows' what it means for something to exist. After all you can open your eyes and see it. But again philosophy is exploring that question from a critical - not necessarily outright sceptical - perspective. — Wayfarer

Everyone knows what it means to exist in the most basic sense; it simply means 'to be actual' as opposed to being imaginary or fictional. But now you may ask what being actual, imaginary or fictional themselves mean. When we are called upon to precisely define or explain terms the problems begin as Augustine pointed out with regard to time.

This is because such concepts can only be defined and explained in terms of other concepts, which in turn can only be defined and explained in terms of yet others and so on. This leads to an endless regression.

But we have an intuitive sense of what such terms mean even if we cannot precisely define and explain that meaning. I would say that intuitive sense derives from experiencing the contexts in which such usages occur.

If we don't have an intuitive understanding of these terms, we are not going to get to an understanding via the endless regress of definition and explanation or via etymology which is fraught with its own set of interpretive pitfalls. How else do you think we could arrive at understanding such concepts? -

Wayfarer

26.2kYou haven't answered the question as to whether you think the claim that possibilities are realities means something beyond what I believe is commonly accepted: namely that there are real possibilities and merely logical possibilities. — Janus

Wayfarer

26.2kYou haven't answered the question as to whether you think the claim that possibilities are realities means something beyond what I believe is commonly accepted: namely that there are real possibilities and merely logical possibilities. — Janus

I think it's an intriguing ontological issue - what kind of existence possibilities have. ' Reality ought also be assigned to certain possibilities, or “potential” realities, that have not yet become “actual.” These potential realities do not exist in spacetime, but nevertheless are “ontological” — that is, real components of existence.' (From the article.) Whereas, I noticed, for example, in another article, debating the possible reality of mathematical objects, that it is said that ' Scientists tend to be empiricists; they imagine the universe to be made up of things we can touch and taste and so on; things we can learn about through observation and experiment. The idea of something existing “outside of space and time” makes empiricists nervous.'

If that idea has not "fallen out of favour" then what exactly is the idea that you think has fallen out of favour? — Janus

I think it harks back to the idea of there being degrees of reality. As I said, the answer to the question 'does the particle exist' just is the probability equation. You may brush it off but I'm suggesting, this is just what caused Einstein to ask the question 'doesn't the moon continue to exist when we're not looking at it?'

I think there might be connection between that idea of there being degrees of reality in sub-atomic physics, with the general idea that reality comes in degrees.

In the context of the kind of idealism I'm advocating, it simply serves to point to the constructive role of perception in experience. That what we take to be simply existent, is also constituted in some sense by our perception of it. Not that it doesn't exist when not perceived, but that 'existence' itself is a manifold, for which perception is foundational.

Notice the convergence with Madhyamaka (Middle Way) philosophy:

By and large, Kaccayana, this world is supported by a polarity, that of existence and non-existence. But when one sees the origination of the world as it actually is with right discernment, "non-existence" with reference to the world does not occur to one. When one sees the cessation of the world as it actually is with right discernment, "existence" with reference to the world does not occur to one. — The Buddha -

Janus

18k' Reality ought also be assigned to certain possibilities, or “potential” realities, that have not yet become “actual.” These potential realities do not exist in spacetime, but nevertheless are “ontological” — that is, real components of existence.' (From the article.)

Janus

18k' Reality ought also be assigned to certain possibilities, or “potential” realities, that have not yet become “actual.” These potential realities do not exist in spacetime, but nevertheless are “ontological” — that is, real components of existence.' (From the article.)

The idea of something existing “outside of space and time” makes empiricists nervous.' — Wayfarer

The interesting {but unfortunately unanswerable) question is as to whether there are real possibilities that never become actual or whether all real possibilities are determined to become actual. Of course, it certainly seems that no possibility exists as anything more than a possibility until (and unless?) it becomes actual.

Does anything exist outside of spacetime (presuming that by "spacetime" we don't mean human phenomenological space and time).? I'd say again that we have no way of determining the truth regarding that question.

The idea of something existing “outside of space and time” makes empiricists nervous.' — Wayfarer

It might make some empiricists nervous...beyond that I think it is an unwarranted generalization. In any case even if it were true, it would be a psychological observation, not a philosophical insight.

I think it harks back to the idea of there being degrees of reality. — Wayfarer

I can't make sense of the idea of degrees of reality, except in terms of degrees of definiteness, which would seem to come down to experiential intensity, and so would be relevant only in regard to human experience. In other words, some things may seem more real (vivid or definite) than others.

As I said, the answer to the question 'does the particle exist' just is the probability equation. You may brush it off but I'm suggesting, this is just what caused Einstein to ask the question 'doesn't the moon continue to exist when we're not looking at it?' — Wayfarer

From the little I know of QM, this is controversial. I don't like to speculate about things of which I have no expert or at least reasonably educated knowledge. What prompted Einstein to ask that question is a matter of psychological speculation. He was probably a realist so it would likely have seemed most plausible to him that the moon does continue to exist when we're not looking.

But again, the answer may vary depending on what we mean by "the moon".; do we mean 'the moon as appearance' or 'the extra-human conditions that give rise to the human perception of what we call 'the moon'. Different ways of thinking about it is what it comes down to as far as I am concerned; there is no final and absolute answer to questions like that.

In the context of the kind of idealism I'm advocating, — Wayfarer

I wonder why you are advocating it—do you think it really matters for human life in general (as opposed to say you or anyone else who cares about it either way) whether idealism or realism is true or at least more accurate?

For example, do you want idealism to be true because you think it would allow for an afterlife? -

Wayfarer

26.2kThe interesting {but unfortunately unanswerable) question is as to whether there are real possibilities that never become actual or whether all real possibilities are determined to become actual. Of course, it certainly seems that no possibility exists as anything more than a possibility until (and unless?) it becomes actual. — Janus

Wayfarer

26.2kThe interesting {but unfortunately unanswerable) question is as to whether there are real possibilities that never become actual or whether all real possibilities are determined to become actual. Of course, it certainly seems that no possibility exists as anything more than a possibility until (and unless?) it becomes actual. — Janus

But the wave equation specifies a range of possibilities. The philosophical question is 'does the electron described by those possibilities exist' to which the answer is, it is kind of real, up until the time it is registered on plate. at which point it becomes definite. This is the much ballyhoed 'collapse of the wave function' that the Everett interpretation seeks to avoid having to acknowledge.

What prompted Einstein to ask that question is a matter of psychological speculation. He was probably a realist so it would likely have seemed most plausible to him that the moon does continue to exist when we're not looking. — Janus

He was indeed a realist, and his debate with Bohr over quantum physics and realism occupied him for decades. That book Quantum by Manjit Kumar is basically about all of that. It's still an open question.

do you want idealism to be true because you think it would allow for an afterlife? — Janus

No, simply because there is no material ultimate, materialism is like a kind of popular myth. -

Metaphysician Undercover

14.9kThe interesting {but unfortunately unanswerable) question is as to whether there are real possibilities that never become actual or whether all real possibilities are determined to become actual. — Janus

Metaphysician Undercover

14.9kThe interesting {but unfortunately unanswerable) question is as to whether there are real possibilities that never become actual or whether all real possibilities are determined to become actual. — Janus

I don't see why you would say this is unanswerable. If there is real possibilities then many do not ever become actual, otherwise they would not be real possibilities. Possibility means that actualization is not necessary. -

sime

1.2kPossibility is an empirical notion. In the case of QM, possibilities either refer to directly observable interference patterns, or they refer to statistical summaries of repeated trials. It is also a good idea not to conflate the empirical meaning of possibility with the epistemic notion referring to possible world semantics, which refers to how people use and think about theories.

sime

1.2kPossibility is an empirical notion. In the case of QM, possibilities either refer to directly observable interference patterns, or they refer to statistical summaries of repeated trials. It is also a good idea not to conflate the empirical meaning of possibility with the epistemic notion referring to possible world semantics, which refers to how people use and think about theories.

IMO, reifying possibility to the status of multiple actual worlds is a mistake born out of equivocating the various uses of the term. -

Wayfarer

26.2kPossibility is an empirical notion. — sime

Wayfarer

26.2kPossibility is an empirical notion. — sime

That is true, but the nature of the object who's existence is only possible is not. And that is the point at issue in this context, as the putative object, a component of the atom, is supposed to be amongst the building blocks of material existence. -

sime

1.2kThat is true, but the nature of the object who's existence is only possible is not. And that is the point at issue in this context, as the putative object, a component of the atom, is supposed to be amongst the building blocks of material existence. — Wayfarer

sime

1.2kThat is true, but the nature of the object who's existence is only possible is not. And that is the point at issue in this context, as the putative object, a component of the atom, is supposed to be amongst the building blocks of material existence. — Wayfarer

If a weather-forecaster states that tomorrows weather is possibly heavy showers, i interpret his sentence to be an empirical report regarding his model of the weather, and not literally to be a reference to tomorrows unobserved weather. (In general, I don't consider predictions to be future-referring in a literal sense, for the very reason that it leads to conflating modalities with theory-content and facts)

Modalities only arise in conversation when a theory is used to make predictions. But the content of theories never mention or appeal to modalities, e.g neither the Bloch sphere describing the state-space of a qubit, nor the Born rule describing a weighted set of alternative experimental outcomes appeal to the existence of modalities. Rather the converse is true. E.g a set of alternative outcomes stated in a theory might be given possible world semantics, but the semantics isn't the empirical content of the theory and so does not ground the theory, in my empiricist opinion. -

Metaphysician Undercover

14.9k

Metaphysician Undercover

14.9k

Put predictions aside for a moment. How would you deal with possibilities in the sense of "it is possible for me to do X, and possible for me to do Y", when X and Y are mutually exclusive? If I act for Y, then X is made to be impossible, and if I act for X, then Y is made to be impossible. However, at the time when I am deciding, both are possible.

How can we model this type of future in relation to this type of past, when both X and Y change from being equally possible in the future, to being one necessary, and one impossible in the past? What happens at "the present" to change the ontological status of these events?

Surely it is not the human act of deciding which causes the change in ontological status, which is known as the difference between future and past. That would mean that human beings have the capacity to create real ontological possibilities when those possibilities would otherwise not be there. How could human beings create possibilities in an otherwise determined world? It makes far more sense to assume that the possibilities are already there, as a characteristic of passing time, and human beings just have the capacity to take advantage of those possibilities.

Welcome to The Philosophy Forum!

Get involved in philosophical discussions about knowledge, truth, language, consciousness, science, politics, religion, logic and mathematics, art, history, and lots more. No ads, no clutter, and very little agreement — just fascinating conversations.

Categories

- Guest category

- Phil. Writing Challenge - June 2025

- The Lounge

- General Philosophy

- Metaphysics & Epistemology

- Philosophy of Mind

- Ethics

- Political Philosophy

- Philosophy of Art

- Logic & Philosophy of Mathematics

- Philosophy of Religion

- Philosophy of Science

- Philosophy of Language

- Interesting Stuff

- Politics and Current Affairs

- Humanities and Social Sciences

- Science and Technology

- Non-English Discussion

- German Discussion

- Spanish Discussion

- Learning Centre

- Resources

- Books and Papers

- Reading groups

- Questions

- Guest Speakers

- David Pearce

- Massimo Pigliucci

- Debates

- Debate Proposals

- Debate Discussion

- Feedback

- Article submissions

- About TPF

- Help

More Discussions

- Other sites we like

- Social media

- Terms of Service

- Sign In

- Created with PlushForums

- © 2026 The Philosophy Forum