-

Wayfarer

26.1kAnything that "is not objectively real" is, of course, "conceivable" — 180 Proof

Wayfarer

26.1kAnything that "is not objectively real" is, of course, "conceivable" — 180 Proof

As stated at the outset, the OP is an argument against the over-valuation of objectivity as the sole criterion of what is real. Accordingly, 'objectively existent' is not the sole criterion for what is real. There are kinds of things, like abstract objects such as numbers and logical principles, which are real but not necessarily objectively existent. There are a priori truths which are not necessarily objective, in that their veracity can be judged without recourse to external experience. More to the point, as you yourself said, the mind itself is not something that can be known objectively, in that it's never the object of cognition (except metaphorically). So when we try to consider what it is, or how it originated, then perhaps the best we can manage is suggestive metaphor. That doesn't necessarily fall to mere fantasy (unless you want to be completely positivistic about it.)

I don't deny that there is an entire vast domain which can be encompassed by the term 'objectively existent' although, as has been pointed out a few times already, this can also be understood as being 'inter-subjectively real'.

Speaking of 'anatman' - the Sanskrit term śūnyatā, meaning 'emptiness', is grounded in the awareness that objects of cognition have no intrinsic being (svabhava, literally 'own being'.) 'Realising emptiness' is the path of understand how the mind misconstrues objects of cognition as being inherently existent. I think the Buddhist expression 'realising emptiness' has a lot to do with seeing through the way in which the mind manufactures meanings about objects which they don't really possess. But it takes a pretty severe inner discipline to pursue that.

I agree with you about chasing enlightenment being very often a cult of the self — Janus

I would have hoped that a Philosophy Forum might be a place to discuss such endeavours, although there are always quite a few tourist members.

I can’t make heads or tails out of self-knowledge. — Mww

It's always struck me as one of the fundamental elements of philosophy, paradoxical and difficult though it might seem. -

Janus

18kI would have hoped that a Philosophy Forum might be a place to discuss such endeavours, although there are always quite a few tourist members. — Wayfarer

Janus

18kI would have hoped that a Philosophy Forum might be a place to discuss such endeavours, although there are always quite a few tourist members. — Wayfarer

Right, well isn't that what we've been doing? I don't deny that the kinds of philosophical practices such as the stoics, the epicureans, and the neo-Platonists pursued could be possible and even transformative today, but that is not what we are doing here. Here we are speculating and critiquing, the very activities which apparently had no place in such spiritual practices. -

180 Proof

16.4k

180 Proof

16.4k

I'm not sure what you mean by "objectively existent" or "objectivity". Please clarify what makes this "criterion" problematic.Accordingly, 'objectively existent' is not the sole criterion for what is real. — Wayfarer

Also, do you reject what I (briefly) say on the thread "What is real?" ...

https://thephilosophyforum.com/discussion/comment/839360 -

Wayfarer

26.1kI'm not sure what you mean by "objectively existent" or "objectivity". Please clarify what makes this "criterion" problematic. — 180 Proof

Wayfarer

26.1kI'm not sure what you mean by "objectively existent" or "objectivity". Please clarify what makes this "criterion" problematic. — 180 Proof

Not so much problematic as limited, not universal. Isn't to limit the scope of truth to what is objective a form of verificationism? As I already said, there are a priori truths, mathematical proofs, and so on which are not objective (meaning 'inherent in the object'), or rather, true in a way that is not necessarily objective in the strict sense. Objectivity is something to be valued - I'm not a relativist - but at the same time, it's not absolute, or rather, its scope is limited. For instance, Newtonian mechanics affords pretty well absolute objectivity when it comes to the laws of motion, but when you get to quantum mechanics, you encounter the whole issue of 'interpretation of the meaning of the theory' which is no longer an objective matter, even if the predictions it makes are extremely accurate.

What I was trying to get at is that I'm aware of the problem of conceiving life in terms of the 'elan vital'. That is very much like the imaginary ghost in the machine as you said. But, I said, If that sounds like vitalism, I am not proposing that 'life' or 'mind' is a substance in any objective sense - it is ill-conceived to consider mind as something objectively real, but it is AS IF there is a something like mind or life that animates the material form of creatures. But to say it is objectively existent is a reification. We can only be aware of it, because it is constitutive of our being, NOT because it is a knowable object or substance. That's what I'm working on trying to clarify.

Also, do you reject what I (briefly) say on the thread "What is real?" ... — 180 Proof

There's not enough detail to really say. -

180 Proof

16.4kOkay, from your vague usage of terms "objectively exist" and "objectivity" what you are saying, Wayf, is too unclear for me to respond further. And since you've not raised compelling objections to my naturalistic position^^ on "mind" in this thread, I rest my case for now.

180 Proof

16.4kOkay, from your vague usage of terms "objectively exist" and "objectivity" what you are saying, Wayf, is too unclear for me to respond further. And since you've not raised compelling objections to my naturalistic position^^ on "mind" in this thread, I rest my case for now.

https://thephilosophyforum.com/discussion/comment/842850 ^^ -

Wayfarer

26.1kwhat you are saying, Wayf, is too unclear for me to respond — 180 Proof

Wayfarer

26.1kwhat you are saying, Wayf, is too unclear for me to respond — 180 Proof

Well, fair enough, but what I was attempting to respond to

Unless solipsism obtains, mind is dependent on (ergo, inseparable from) More/Other-than-mind, no? and that "experience" consists of phenomenal traces (or outputs) of the 'entangled, or reflexive, interactivity' of mind with More/Other-than-mind? — 180 Proof

is hardly a model of clarity itself, you must admit. -

plaque flag

2.7kabsent an observer, whatever exists is unintelligible and meaningless as a matter of fact and principle. — Wayfarer

plaque flag

2.7kabsent an observer, whatever exists is unintelligible and meaningless as a matter of fact and principle. — Wayfarer

So do we agree that the cup, unobserved in the cupboard, still has a handle? I'm going to take it that we do, that the cup in the cupboard is not the sort of thing that you are talking about as "absent an observer". — Banno

I get what Wayf is trying to say here, but there 'is' not a [metaphysical] subject except as a perspectival form of being. Husserl's discussion of spatial objects is helpful here. What we tend to mean by a cup is that familiar object viewed perspectively through human eyes. I can never see all of it at once. I can see it from this place or that, in this lighting or that. Our embodied experience has always been and seeming must always continue to be 'perspectival.'

We don't know what we could even mean by the cup 'apart from human cognition'. Or rather such a statement is paradoxical, aimed of course precisely at the same human cognition which is supposed to contemplate the mystically Real cup its own absence.

The 'objective' cup is something like the cup from a (virtual, postulated) 'average' human perspective. -

unenlightened

10kQuite simply, swapping places does not imply swapping perspectives, because the unique particularities of the being brings a lot to the perspective. If swapping perspectives was just a matter of swapping places, you could take a dog's perspective, or a cat's perspective, by taking that creature's place. But this is all wrong. And that is why "walking in someone else's shoes" is a matter of understanding the other person, not a matter of swapping physical positions. — Metaphysician Undercover

unenlightened

10kQuite simply, swapping places does not imply swapping perspectives, because the unique particularities of the being brings a lot to the perspective. If swapping perspectives was just a matter of swapping places, you could take a dog's perspective, or a cat's perspective, by taking that creature's place. But this is all wrong. And that is why "walking in someone else's shoes" is a matter of understanding the other person, not a matter of swapping physical positions. — Metaphysician Undercover

Yes, you are quite right. Even the map-reading is not simple; the information is there in the contours, but working out what can be seen from where is complex. Similarly, one can know something of a persons's economic position, social and psychological condition and perhaps work out to some extent their psycho-social 'perspective'. And if one understands a dog's sensibilities, the same applies. That you bring up such particularities shows that you can do so to some extent, and shows, again, that they are features of the world.

I think this is what the thread is suggesting; that the objective world is an abstract theoretical construct, and to arrive at the real, one has 'to put' back the subjectivity that has been discounted. -

plaque flag

2.7kWhatever experience we have or knowledge we possess, it always occurs to a subject — a subject which only ever appears as us, as subject, not to us, as object. — Wayfarer

plaque flag

2.7kWhatever experience we have or knowledge we possess, it always occurs to a subject — a subject which only ever appears as us, as subject, not to us, as object. — Wayfarer

I basically agree. We can only speak with confidence from our actual, embodied experience. We know nothing about a world from no perspective at all. We know the world for sapience. Some have postulated a to-me-paradoxical urstuff, admittedly not without their reasons.

But others postulate too much on the side of the subject. It's the world that is given perspectively, not some private dream. Though dreamers and dreams are also given. Still, language is more social than individual, so we intend always the same world, and that includes the toothaches of others, which figure like prime numbers and pretzels in the same kind of justifications of claims and deeds. -

Jamal

11.7k

Jamal

11.7k

A very nicely presented argument which I think is substantially wrong. I hope you don’t mind if I boil things down…

The following analogical argument is obviously wrong (or is it?):

You cannot look at a landscape except from a point of view.

Therefore the landscape is constituted by (or created by) your point of view.

So the question is either: what is the crucial difference in the case of empirical reality in general (as opposed to a landscape) that turns the argument into a good one; or what are the missing premises? -

plaque flag

2.7k

plaque flag

2.7k

The following analogical argument is obviously wrong (or is it?):

You cannot look at a landscape except from a point of view.

Therefore the landscape is constituted by (or created by) your point of view.

So the question is either: what is the crucial difference in the case of empirical reality in general (as opposed to a landscape) that turns the argument into a good one; or what are the missing premises? — Jamal

:up:

The subjectivist camp is right that the world is always given perspectively, but they don't squeeze enough juice from the fact that it's the world, our world that is so given. Logic is ours not mine. We always intend the one and only 'landscape.'

My mind didn't create our world, but maybe my mind, understood as this world entire but from a point of view, has a genuine if merely supporting ontological role. -

plaque flag

2.7k

plaque flag

2.7k

:up:the objective world is an abstract theoretical construct, and to arrive at the real, one has 'to put' back the subjectivity that has been discounted. — unenlightened

In other words, the scientific image is (of course, in retrospect?) just a useful image. It's a map that deserves respect, but it's bonkers ontologically -- if taken as some kind of self-supporting independently-meaningful Thing. -

plaque flag

2.7kFor it doesn't matter if I believe that a eating a rotten apple is healthy, the reality of illness will follow. If it were the case that there was nothing underlying to model on, then there would never be any contradictions to the models we create. — Philosophim

plaque flag

2.7kFor it doesn't matter if I believe that a eating a rotten apple is healthy, the reality of illness will follow. If it were the case that there was nothing underlying to model on, then there would never be any contradictions to the models we create. — Philosophim

I hear you, but we replace one fallible belief with another. I do think you nailed the practical sense of 'reality.' But I don't think you've made a case for the truly independent object (the one from no perspective.) -

Wayfarer

26.1kYou cannot look at a landscape except from a point of view.

Wayfarer

26.1kYou cannot look at a landscape except from a point of view.

Therefore the landscape is constituted by (or created by) your point of view. — Jamal

That was given as an illustrative analogy, not as the main point of the argument. Note also I that I say that a perspective is required for any judgement as to what exists. There can be no answer to the question 'does [the object] exist irrespective of any judgement?' as that question requires that the questioner already has [the object] in mind, in order to frame the question. You may plausibly accept that [the object] continues to exist in the absence of any perspective, but that remains conjecture, even if plausible.

But the main part of the argument occurs further on, where I say 'there is no need for me to deny that the Universe ('the object') is real independently of your mind or mine, or of any specific, individual mind. Put another way, it is empirically true that the Universe exists independently of any particular mind. But what we know of its existence is inextricably bound by and to the mind we have, and so, in that sense, reality is not straightforwardly objective. It is not solely constituted by objects and their relations. Reality has an inextricably mental aspect, which itself is never revealed in empirical analysis ¹. Whatever experience we have or knowledge we possess, it always occurs to a subject — a subject which only ever appears as us, as subject, not to us, as object.'

[1] This insight is central to the philosophy of Immanuel Kant. Kant has been described as the ‘godfather of modern cognitive science’ for his insights into the workings of the mind. -

Wayfarer

26.1kLogic is ours not mine. We always intend the one and only 'landscape.' — plaque flag

Wayfarer

26.1kLogic is ours not mine. We always intend the one and only 'landscape.' — plaque flag

Indeed. That is how language, mathematics, and all forms of communication are effective - they are part of a 'shared mindscape', so to speak, that have agreed references that we all understand. Or rather, that all those of our cultural type understand. (Because, as Wittgenstein says, even if a lion could speak, we would not understanding him.)

But this is also why my approach is not solipsistic. When I say the world is 'mind-made' I don't mean made only by my mind, but is constituted by the shared reality of humankind, which is an irreducibly mental foundation. -

Wayfarer

26.1kSo the question is either: what is the crucial difference in the case of empirical reality in general (as opposed to a landscape) that turns the argument into a good one; or what are the missing premises? — Jamal

Wayfarer

26.1kSo the question is either: what is the crucial difference in the case of empirical reality in general (as opposed to a landscape) that turns the argument into a good one; or what are the missing premises? — Jamal

What I said was that 'empirical reality in general is not solely constituted by objects and their relations but has an inextricably mental aspect, which itself is never revealed in empirical analysis' - thereby pointing out a lack or absence in the empirical account, namely, the inextricably mental. Doesn't that address your question? -

Wayfarer

26.1kCross-checked a possible reference against ChatGPT:

Wayfarer

26.1kCross-checked a possible reference against ChatGPT:

Q: What is 'the myth of the given' in Sellars?

A. In traditional empiricism, sensory experiences (or "sense data") were thought to provide a direct, foundational basis for knowledge. This foundation was "given" to the mind in a direct, unmediated fashion. From these basic sensory experiences, the mind could then build more complex structures of knowledge.

Sellars criticized this view by arguing against the idea that there are immediate and self-justifying foundations for our beliefs. He challenged the notion that sensory experiences could serve as a non-conceptual, unmediated foundation for knowledge. In essence, he argued that what we often take to be raw, uninterpreted sensory data are already shaped and structured by our conceptual framework.

For Sellars, all knowledge is mediated by concepts, and there is no direct, unmediated access to the world. Even our most basic perceptual experiences are informed by a backdrop of concepts, beliefs, and prior knowledge. Thus, to treat any part of our knowledge as simply "given" without the influence of concepts or beliefs is a mistake. This idea is encapsulated in his critique of "the myth of the given." -

Jamal

11.7kWhat I said was that 'empirical reality in general is not solely constituted by objects and their relations but has an inextricably mental aspect, which itself is never revealed in empirical analysis' - thereby pointing out a lack or absence in the empirical account, namely, the inextricably mental. Doesn't that address your question? — Wayfarer

Jamal

11.7kWhat I said was that 'empirical reality in general is not solely constituted by objects and their relations but has an inextricably mental aspect, which itself is never revealed in empirical analysis' - thereby pointing out a lack or absence in the empirical account, namely, the inextricably mental. Doesn't that address your question? — Wayfarer

I’m not sure. On the face of it it’s more or less repeating the analogical argument with empirical reality substituted for the landscape. Also, isn’t there a tension—it could be worse than just a tension, I’m not sure—between the claim that the mental aspect of empirical reality is not revealed empirically, and your appeal to cognitive science? Kant’s transcendental subject is a kind of vanishing point, not a real mind. -

Wayfarer

26.1kisn’t there a tension between the claim that the mental aspect of empirical reality is not revealed empirically, and your appeal to cognitive science? — Jamal

Wayfarer

26.1kisn’t there a tension between the claim that the mental aspect of empirical reality is not revealed empirically, and your appeal to cognitive science? — Jamal

'It might be thought that a neuroscientific approach to the nature of the mind will be inclined towards just the kind of physicalist naturalism that this essay has set out to criticize. But, and perhaps ironically, that is not necessarily so. Many neuroscientists stress that the world we perceive is not an exact replication of external stimuli, but rather is actively constructed by the brain in a dynamic and interleaved process from one moment to the next. Every act of perception involves the processes of filtering, amplifying, and interpretation of sensory data — physical, environmental, somatic — and in the case of h. sapiens, refracted through language and reason. These are the constituents of our mental life which constitute our world. The world is, as phenomenologists like to put it, a lebenswelt, a world of lived meanings.'

Kant’s transcendental subject is a kind of vanishing point, not a real mind. — Jamal

In my taxonomical schema, real but not phenomenally existent.

Incidentally, that above passage has a footnote reference in the original to this video:

I love that Richard Dawkins appears as Witness for the Defense (of objectivity) :-) -

Mww

5.4kWhatever experience we have or knowledge we possess, it always occurs to a subject — a subject which only ever appears as us, as subject, not to us, as object.' — Wayfarer

Mww

5.4kWhatever experience we have or knowledge we possess, it always occurs to a subject — a subject which only ever appears as us, as subject, not to us, as object.' — Wayfarer

Paradox resolved. Self-knowledge is a transcendental paralogism, a logical misstep of pure reason, re: knowledge of self treats that to which knowledge belongs, as object the knowledge is about. (B411)

————

It's not just me then.…. — Tom Storm

Reason: the source of both wondrous insight and debilitating confusion. -

plaque flag

2.7kI got a copy of Pain and Pleasure by Thomas Szasz, and reads like a work of metaphysics, in a good way. Szasz quotes Russell making surprisingly (to me) phenomenological points that seem relevant to this thread.

plaque flag

2.7kI got a copy of Pain and Pleasure by Thomas Szasz, and reads like a work of metaphysics, in a good way. Szasz quotes Russell making surprisingly (to me) phenomenological points that seem relevant to this thread.

When a crowd of people all observe a rocket bursting, they will ignore whatever there is reason to think peculiar and personal in their experience, and will not realize without an effort that there is any

private element in what they see. But they can, if necessary, become aware of these elements. One part of the crowd sees the rocket on the right, one on the left, and so on. Thus when each person's perception is studied in its fullness, and not in the abstract form which is most convenient for conveying information about the outside world, the perception becomes a datum for psychology. But although every physical datum is derived from a system of psychological data, the converse is not the case. Sensations resulting from a stimulus within the body will naturally not be felt by other people ; if I have a stomach-ache I am in no degree surprised to find that others are not similarly afflicted. — Russell

I agree w/ Russell (and Husserl) that we tend to look right thru our own looking. The personal and typically irrelevant how is forgotten in the worldly what. It takes work to really see our own seeing, because such seeing of seeing is even potentially counterpractical. -

plaque flag

2.7kThat is how language, mathematics, and all forms of communication are effective - they are part of a 'shared mindscape', so to speak, that have agreed references that we all understand. Or rather, that all those of our cultural type understand. — Wayfarer

plaque flag

2.7kThat is how language, mathematics, and all forms of communication are effective - they are part of a 'shared mindscape', so to speak, that have agreed references that we all understand. Or rather, that all those of our cultural type understand. — Wayfarer

I think we agree here. This is Geist, spirit, form of life, culture, the they, one, the who of everyday dasein. -

plaque flag

2.7kBut this is also why my approach is not solipsistic. When I say the world is 'mind-made' I don't mean made only by my mind, but is constituted by the shared reality of humankind, which is an irreducibly mental foundation. — Wayfarer

plaque flag

2.7kBut this is also why my approach is not solipsistic. When I say the world is 'mind-made' I don't mean made only by my mind, but is constituted by the shared reality of humankind, which is an irreducibly mental foundation. — Wayfarer

Our views aren't that far apart probably. I don't think you are being solipsistic, by the way. And the timebinding human species is the best candidate for a transcendental ego. But consider that this species is part of what it finds in the world. So I'd call it a sine qua non. And what is awareness of...if not the world ? The 'mental,' grasped most profoundly, is precisely the very being of its of 'objects.'

'I' am the there itself. But this is not the psychological 'I' or the person with a credit score. It's vanishingly pure witness, which no longer deserves anthropomorphic trappings, having been recognized as [the perspectival character of ] being itself. -

plaque flag

2.7kReality has an inextricably mental aspect, which itself is never revealed in empirical analysis ¹. Whatever experience we have or knowledge we possess, it always occurs to a subject — a subject which only ever appears as us, as subject, not to us, as object.' — Wayfarer

plaque flag

2.7kReality has an inextricably mental aspect, which itself is never revealed in empirical analysis ¹. Whatever experience we have or knowledge we possess, it always occurs to a subject — a subject which only ever appears as us, as subject, not to us, as object.' — Wayfarer

I tend to agree with the spirit of what you are saying in this thread, but I think this metaphysical subject must be dissolved,

https://plato.stanford.edu/entries/sartre/#TranEgoDiscInteInstead of a transcendental subject, the Ego must consequently be understood as a transcendent object similar to any other object, with the only difference that it is given to us through a particular kind of experience, i.e., reflection. The Ego, Sartre argues, “is outside, in the world. It is a being of the world, like the Ego of another” (Sartre 1936a [1957: 31; 2004: 1]).

When I run after a streetcar, when I look at the time, when I am absorbed in contemplating a portrait, there is no I. […] In fact I am plunged in the world of objects; it is they which constitute the unity of my consciousness; […] but me, I have disappeared; I have annihilated myself. There is no place for me on this level. (Sartre 1936a [1957: 49; 2004: 8])

When I run after the streetcar, my consciousness is absorbed in the relation to its intentional object, “the streetcar-having-to-be-overtaken”, and there is no trace of the “I” in such lived-experience. I do not need to be aware of my intention to take the streetcar, since the object itself appears as having-to-be-overtaken, and the subjective properties of my experience disappear in the intentional relation to the object. They are lived-through without any reference to the experiencing subject (or to the fact that this experience has to be experienced by someone). This particular feature derives from the diaphanousness of lived-experiences.

This is close to Heidegger's being-in-the-world. The 'I' is the world, but this world exists in the style of a sentient citizen's chasing of a streetcar. -

Metaphysician Undercover

14.8kI think this is what the thread is suggesting; that the objective world is an abstract theoretical construct, and to arrive at the real, one has 'to put' back the subjectivity that has been discounted. — unenlightened

Metaphysician Undercover

14.8kI think this is what the thread is suggesting; that the objective world is an abstract theoretical construct, and to arrive at the real, one has 'to put' back the subjectivity that has been discounted. — unenlightened

I agree with this, and I think the issue is the question of how we can arrive at a "correct way" to put back the subjectivity. If we define "correct way" as the way that follows the conventions, and these conventions are the ones which are consistent with the abstract theoretical construct, then any application of the "correct way" will not put back the subjectivity, as desired, because it will just create a new aspect of the same old "objective world". To "put back the subjectivity" requires including the features of subjectivity which are outside the boundaries of convention.

The interesting aspect of this type of thread, is that there is a significant number of hard realists who flatly refuse to acknowledge this need to put back the subjectivity, as required to have an honest approach to reality. Since these people think that "the real" can be arrived at simply by following the conventions, they are in great agreement with each other, and you'll see them on these threads, slapping each other on the back, giving thumbs up and high fives etc.. On the other hand, those who apprehend and agree with this need, "to put back the subjectivity" as a requirement for an approach to "the real", can never agree with each other as to how this ought to be done. This is because the very thing that they are arguing for, the need to respect the concrete base of subjectivity, as very real, and a very essential and true part of reality, is also the very same thing which manifests as the differences between us, which make agreement between us into a very difficult matter.

So we are broken into two groups. The first group agrees with each other, and commits to an ontology which denies the significance or importance of perspectival difference. The "objective world" is the one we understand through certain conventions of abstract theoretical thought, and those who see "the world" in a different way are by definition "wrong", therefore we can exclude them, and their absurd perspectives, as irrelevant to our objective reality. This first group has explicit terms of agreement supported by the conventions of language, so there is great conformity and unity amongst them. The second group, which supports the real, essential, and significant nature of difference, is pushed further and further away from the first, by the first, so that the first can apply terms of mental illness and things like that, to the second, as required to support the illusion of the reality of their "objective world" construct.

Now the second group, by the very nature of what they are arguing for, lacks unity. Because of this lack of unity, they will always be "wrong", and even my act of classing them together as one group is wrong. They are better characterized as wayward individuals lacking what is required for categorization. And even if some of them find points of agreement, that small group will still be in the minority compared to the first group, and therefore wrong. This ought to serve as a demonstration of how the first group is always "correct", but correct by their own theoretical constructs of what is true and real, and not "correct" by the true reality of honest subjectivity.

Here's an evolutionary example which may or may not be helpful to some. Imagine a species appears on earth, and flourishes greatly, to the point where it overruns and inhabits every space of the entire plane. The species does not understand the toxicity of its own waste, such that its own annihilation from the effects of its own waste becomes imminent. At this point individuals come into existence amidst the toxicity of "the species", demonstrating various differences, perhaps mutations caused by the toxic elements of the waste. Each individual separates from "the species" in its own way, with an instinctual form of knowledge, knowing that the species is toxic and that there is a need to separate from it. Not one of these individuals is "normal" by the conventions of "the species", and not one of them has the characteristics required to be called a new species. Each one is a monstrosity or deformity relative to "the species" They are all within some intermediate condition not covered by the norms of our "objective world" so they are simply mutations. However, these differences are essential and necessary for the continuation of all the features of that life form, which have been progressively building for millions of years, producing the necessary conditions for its extreme flourishment, and this would all be completely lost if the species proceeded to annihilate itself prior to the individuals establishing something new.

The subjectivist camp is right that the world is always given perspectively, but they don't squeeze enough juice from the fact that it's the world, our world that is so given. Logic is ours not mine. We always intend the one and only 'landscape.' — plaque flag

This is very good evidence of the problem I discuss above. In reality, the assumption of "the world" is only supported by the truth of "our world". And "our world" implies an inter-subjectivity, of agreements and conventions. So long as agreement holds, there is such a thing as "the world". But as more and more people see faults and defects in "our world", and those who cling to "our world" refuse to address these faults because they automatically reject those people as simply "wrong", insignificant and irrelevant, the foundation of "our world" gets shakier and shakier as the concrete which supports it, is that very agreement which is not being properly maintained. -

plaque flag

2.7kI offer this not as an appeal to authority but only as potentially useful.

plaque flag

2.7kI offer this not as an appeal to authority but only as potentially useful.

Is phenomenological research solipsistic research? Does it restrict the research to the individual I and, more precisely, to the area of its individual psychic phenomena? It is anything but this. Solus ipse — that would mean I alone exist or I disengage everything remaining of the world, excepting only myself and my psychic states and acts.

On the contrary, as a phenomenologist, I disengage myself just as I disengage everyone else and the entire world, and no less my psychic states and acts, which, as my states and acts, are precisely nature. One may say that the nonsensical epistemology of solipsism emerges when, being ignorant of the radical principle of the phenomenological reduction, yet similarly intent on suspending all transcendence, one confuses the psychological and the psychologistic immanence with the genuine phenomenological immanence. — Husserl

I disengage myself just as I disengage everyone else and the entire world, and no less my psychic states and acts, which, as my states and acts, are precisely nature.

I read this as: the ego, which might be postulated as constituting, is at least also one more thing in the world, so that it would have to be self-constituting. It seems cleaner to me to indeed grant the lived body the status of a sine qua non...but to hesitate to speak of the priority of mentality. The lifeworld is 'given' as a rushing river, as a symphony. I can't see without a brain, but I also need eyes. But then I also need something in the world to see. And perception is conceptual (Sellars was mentioned above), so I need a linguistic conceptual community too. This without-which-nothing or condition-for-the-possibility approach memorably appears in The Fire Sermon.

The mind is burning, ideas are burning, mind-consciousness is burning, mind-contact is burning, also whatever is felt as pleasant or painful or neither-painful-nor-pleasant that arises with mind-contact for its indispensable condition, that too is burning. Burning with what? Burning with the fire of lust, with the fire of hate, with the fire of delusion. — Fire Sermon

I can sum up by suggesting that it's enough to challenge the intelligibility of the 'pure' object. We probably don't want to put ourselves in the vulnerable position of proposing a pure subject. -

wonderer1

2.4kThe interesting aspect of this type of thread, is that there is a significant number of hard realists who flatly refuse to acknowledge this need to put back the subjectivity, as required to have an honest approach to reality. Since these people think that "the real" can be arrived at simply by following the conventions, they are in great agreement with each other, and you'll see them on these threads, slapping each other on the back, giving thumbs up and high fives etc.. On the other hand, those who apprehend and agree with this need, "to put back the subjectivity" as a requirement for an approach to "the real", can never agree with each other as to how this ought to be done. This is because the very thing that they are arguing for, the need to respect the concrete base of subjectivity, as very real, and a very essential and true part of reality, is also the very same thing which manifests as the differences between us, which make agreement between us into a very difficult matter. — Metaphysician Undercover

wonderer1

2.4kThe interesting aspect of this type of thread, is that there is a significant number of hard realists who flatly refuse to acknowledge this need to put back the subjectivity, as required to have an honest approach to reality. Since these people think that "the real" can be arrived at simply by following the conventions, they are in great agreement with each other, and you'll see them on these threads, slapping each other on the back, giving thumbs up and high fives etc.. On the other hand, those who apprehend and agree with this need, "to put back the subjectivity" as a requirement for an approach to "the real", can never agree with each other as to how this ought to be done. This is because the very thing that they are arguing for, the need to respect the concrete base of subjectivity, as very real, and a very essential and true part of reality, is also the very same thing which manifests as the differences between us, which make agreement between us into a very difficult matter. — Metaphysician Undercover

What do you mean by "put back the subjectivity"? -

Wayfarer

26.1kSelf-knowledge is a transcendental paralogism, a logical misstep of pure reason... — Mww

Wayfarer

26.1kSelf-knowledge is a transcendental paralogism, a logical misstep of pure reason... — Mww

I always thought the maxim 'know thyself' was simply about seeing through your own delusions and false hopes. It doesn't necessarily pre-suppose a 'real self' that needs to be known, except maybe as a figure of speech. Self knowledge as an important aspect of wisdom and maturity.

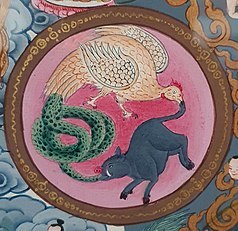

Burning with the fire of lust, with the fire of hate, with the fire of delusion.

— Fire Sermon — plaque flag

Those are the 'three poisons' of Buddhism, represented iconographically as the pig (greed) snake (hate) and rooster (stupidity/delusion) chasing each other around an endless circle (saṃsāra).

These are said to be the chief motivators of the 'deluded worlding', replaced in the wise by their opposites, namely:

amoha (non-delusion) or paññā (wisdom)

alobha (non-attachment) or dāna (generosity)

adveṣa (non-hatred) or mettā (loving-kindness)

Welcome to The Philosophy Forum!

Get involved in philosophical discussions about knowledge, truth, language, consciousness, science, politics, religion, logic and mathematics, art, history, and lots more. No ads, no clutter, and very little agreement — just fascinating conversations.

Categories

- Guest category

- Phil. Writing Challenge - June 2025

- The Lounge

- General Philosophy

- Metaphysics & Epistemology

- Philosophy of Mind

- Ethics

- Political Philosophy

- Philosophy of Art

- Logic & Philosophy of Mathematics

- Philosophy of Religion

- Philosophy of Science

- Philosophy of Language

- Interesting Stuff

- Politics and Current Affairs

- Humanities and Social Sciences

- Science and Technology

- Non-English Discussion

- German Discussion

- Spanish Discussion

- Learning Centre

- Resources

- Books and Papers

- Reading groups

- Questions

- Guest Speakers

- David Pearce

- Massimo Pigliucci

- Debates

- Debate Proposals

- Debate Discussion

- Feedback

- Article submissions

- About TPF

- Help

More Discussions

- Other sites we like

- Social media

- Terms of Service

- Sign In

- Created with PlushForums

- © 2026 The Philosophy Forum