-

Hanover

15.3k[and if "empirical" denotes how something is experienced or appears to us — 180 Proof

Hanover

15.3k[and if "empirical" denotes how something is experienced or appears to us — 180 Proof

I'd argue that this definition of empirical realism is actually of indirect realism in particular and not of empirical realism generally (as direct realism wouldn't allow for a distinction between the real and perceived).

I take Kant's position to deal heavily with how the mind organizes perceptions and what is required for the perception. As to the thing in itself, I take that as beyond the limit of perception and not knowable.

Because of the emphasis upon the mind's peculiar way of knowing things, his position is referred to as transcendental, and because of the mind's inability to know the thing in itself, it's idealistic, thus transcendental idealism and not empirical realism better describes Kant.

The unknowablity of the thing in itself is a major problem with Kant, as it cannot even be said it's causative of the perception. -

Jamal

11.7ktranscendental idealism and not empirical realism better describes Kant. — Hanover

Jamal

11.7ktranscendental idealism and not empirical realism better describes Kant. — Hanover

Your summary of Kant is fine, but here you miss the fact that transcendental idealism and empirical realism are complementary. Kant says it explicitly: he's arguing for both, because they go together. And on the other side, he's against transcendental realism and empirical idealism. This is the structure of his system. -

Michael

16.8kWell, that's not the common view. Where did you get this from, or is it just yours? — Banno

Michael

16.8kWell, that's not the common view. Where did you get this from, or is it just yours? — Banno

https://plato.stanford.edu/entries/idealism/

Idealism in sense (1) has been called “metaphysical” or “ontological idealism”, while idealism in sense (2) has been called “formal” or “epistemological idealism”. The modern paradigm of idealism in sense (1) might be considered to be George Berkeley’s “immaterialism”, according to which all that exists are ideas and the minds, less than divine or divine, that have them.

...

We thus agree with A.C. Ewing, who wrote in 1934 that all forms of idealism

"have in common the view that there can be no physical objects existing apart from some experience, and this might perhaps be taken as the definition of idealism..."

...

We also agree with Jeremy Dunham, Iain Hamilton Grant, and Sean Watson when they write that

"the idealist, rather than being anti-realist, is in fact … a realist concerning elements more usually dismissed from reality. (Dunham, Grant, & Watson 2011: 4)"

namely mind of some kind or other: the idealist denies the mind-independent reality of matter, but hardly denies the reality of mind....

Metaphysical arguments proceed by identifying some general constraints on existence and arguing that only minds of some sort or other satisfy such conditions...

https://plato.stanford.edu/entries/dualism/

Materialist views say that, despite appearances to the contrary, mental states are just physical states.

…

Idealist views say that physical states are really mental.

…

Dualist views (the subject of this entry) say that the mental and the physical are both real and neither can be assimilated to the other.

Idealism is concerned with what does and doesn't exist. This has no prima facie relevance to truth, except insofar as it then follows that "X exists" is only true if X is reducible to mental phenomena. -

Michael

16.8kBut then if nothing is external, the difference between internal and external dissipates. — Banno

Michael

16.8kBut then if nothing is external, the difference between internal and external dissipates. — Banno

Words and concepts can have a meaning even if nothing exists which satisfies the conditions of that meaning. Nothing is "supernatural", but the difference between the natural and the supernatural doesn't dissipate. -

Gnomon

4.3k

Gnomon

4.3k

Kastrup seems to be swimming in the same esoteric waters that my own thesis merely dabbles in.I will admit I am interested in Bernardo Kastrup's 'analytical idealism'. — Wayfarer

The main difference is that he claims to have personally experienced "The Other" (Universal Mind?), while I lack such adventures into the non-physical. For me, "Other" and "G*D" are rationally inferred & hypothetical , not directly known & experiential. Anyway, his "analytical idealism" seems to be generally amenable to the fundamental role of abstract information as described in Enformationism.

However, since my mundane experience seems to fit the ordinary sensations of the majority of people, for all practical purposes (science) I accept the existence of an "external reality", as a communal mental model (paradigm). But for impractical philosophical purposes, I entertain the possibility that Rational Information (including Mathematics) is more fundamental that Physical Matter. For hardline Atheists, that puts me into their broad sh*t-can category of religious believers in invisible gods & ghosts & spooks & spirits. And those scathing skeptics won't accept my protestations to the contrary.

Instead, I believe that the purpose of Philosophy is to explore the metaphysical realm of "Ideas", beyond the physical limits of empirical science, while avoiding the slippery slope into blind faith. Does that openness to possibilities make me an un-skeptical believer in Idealism, as an irrational religious faith? I hope not. :smile:

Information Realism :

Artificial Intelligence researcher, Kastrup, seems to be finding evidence to support the ancient philosophy of Idealism, which further weakens the equally venerable Atomic & Materialistic paradigms of modern science. He is the author of a book, The Idea of The World, which argues for the “mental nature of reality”, also known as “metaphysical realism” . In this article he discusses “information realism”, and begins by quoting physicist Max Tegmark, author of the Mathematical Universe Hypothesis. “For Tegmark, the universe is a ‘set of abstract entities with relations between them,’ . . . Matter is done away with and only information itself is taken to be ultimately real.” Kastrup then describes how reductive methods failed to find the definitive atom, and instead discovered only amorphous fields. “At the bottom of the chain of physical reduction there are only elusive, phantasmal entities we label as “energy” and “fields”—abstract conceptual tools for describing nature, which themselves seem to lack any real, concrete essence.” This is the conceptual conundrum that launched by own investigation into “the mental nature of reality”, which I call Enformationism.

http://bothandblog4.enformationism.info/page18.html

Contra Idealism :

I develop this unresolved paradox into a rigorous argument against Analytic Idealism. . . . . Some of the omissions of this model given its theorising are that it fails to adequately account for:

1. The apparent fine-tuning of the universe: it proposes that mind at large is unreflective and non-self-aware, and it is hard to see how it could then be intelligent - which would seem to be required to design our universe.

2. The existence and extent of evil in our reality. A monistic theory (single subject of consciousness; single ontological substance) somehow has to reconcile the bad and the good, whereas a dualistic theory (distinct subjects of consciousness with differing essential natures, both good and evil) assumes no need for reconciliation. ]

https://creativeandcritical.net/ontology/analysing-the-analytic-idealism-of-bernardo-kastrup

Note -- My own thesis does attempt to account for those apparent deficiencies of Reality, primarily by denying the Genesis account of the intention behind Creation. -

Banno

30.6kSure. The question remains, what is external doing in the phrase "external reality"?

Banno

30.6kSure. The question remains, what is external doing in the phrase "external reality"?

Also not following how you got "idealism as simply being a substance monism" from "all that exists are ideas and the minds, less than divine or divine, that have them" or "there can be no physical objects existing apart from some experience, and this might perhaps be taken as the definition of idealism..", " the idealist denies the mind-independent reality of matter", or "Metaphysical arguments proceed by identifying some general constraints on existence and arguing that only minds of some sort or other satisfy such conditions"... even on bold.

Some Aristotelian notion of substance, I suppose. -

Michael

16.8kSure. The question remains, what is external doing in the phrase "external reality"? — Banno

Michael

16.8kSure. The question remains, what is external doing in the phrase "external reality"? — Banno

"External reality" refers to the notion of a domain of objects existing independently ("outside") of any subjective mental phenomena.

Also not following how you got "idealism as simply being a substance monism" from "all that exists are ideas and the minds, less than divine or divine, that have them" or "there can be no physical objects existing apart from some experience, and this might perhaps be taken as the definition of idealism..", " the idealist denies the mind-independent reality of matter", or "Metaphysical arguments proceed by identifying some general constraints on existence and arguing that only minds of some sort or other satisfy such conditions"... even on bold.

Some Aristotelian notion of substance, I suppose. — Banno

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Monism

Substance monism asserts that a variety of existing things can be explained in terms of a single reality or substance. Substance monism posits that only one kind of substance exists, although many things may be made up of this substance, e.g., matter or mind.

-

bert1

2.2k@Michael

bert1

2.2k@Michael

Back to basics!

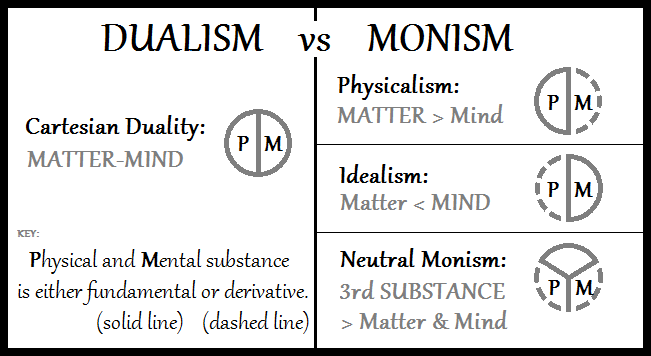

I guess non-emergent monistic property dualism would be one unbroken circle with a P and an M in it. Is that right?

Emergent property dualism would be the same as the pysicalism diagram I suppose. So I guess physicalist emergentism divides into two, weak emergentism (no property dualism) and strong emergentism (property dualism). We should do another more complex diagram to include more positions. I think it's useful. Might head off a lot of pointless exchanges if we could all see the map of the various positions. @Nickolasgaspar Where are you in this scheme? Outside it throwing rotten eggs? -

Janus

18kIF Kant is an "empirical realist",

Janus

18kIF Kant is an "empirical realist",

and if "empirical" denotes how something is experienced or appears to us

and if Kant's ding-an-sich, or "in itself", denotes reality,

THEN, for the "empirical realist", appearances (i.e. "phenomena") are reality – or only aspects of reality;

THEREFORE, "for us"-"in itself" is a distinction without a difference either epistemically or onticly.

My re-question:

Where does my thinking about (the implications of) Kant's "empirical realism" go wrong? :chin: — 180 Proof

I am getting to this a tad tardily, but anyhow...

It's an interesting question whether Kant's "in itself" denotes a reality. I think it must since it is thought as being what is in itself independently of the appearances it, whatever it is, gives rise to.

As I wrote in an earlier post:

I have sometimes thought that Kant has his characterization of his philosophy as empirical realist and transcendental idealist backwards. We know the empirical world only via ideas; as I like to say the empirical world is a collective representation and in that sense it is ideal. About the transcendental we have no idea, except that if it is at all it must be real.

When Kant says the in-itself is transcendentally ideal, he seems to mean that it is so for us, since we have no sensory access to its inherent nature, but only to the appearances it gives rise to. So, as you said earlier it is an epistemological perspective, not an ontological perspective. Thinking from our perspective we can say that the world of the senses is real, and the world of ideas, which the in itself can only inhabit for us, is ideal.

If we take an ontological standpoint it seems to me that is reversed, the empirical world, being a collective representation is ideal, although founded in the transcendentally real. We could say that the world of the senses is just an aspect of the real, which seems to be what you are saying, and I think that makes sense too, although we must also admit that it is mediated by ideas.

In Kant's own words (as translated): "Thoughts without content are empty, intuitions without concepts are blind. The understanding can intuit nothing, the senses can think nothing. Only through their unison can knowledge arise.".

There is of course the basic dualistic character of Kant's philosophy in the sense of phenomena/ noumena or for us/ in itself, but that just reflects the ineliminably dualistic nature of all our thinking, and in no way entails substance dualism. — Janus

I read Kant's "dualistic thinking" as (an attempt at) 'ontologizing epistemology' (i.e. reify knowing) by designating "for us" the tip "phenomena" of the iceberg "in itself" above the water line "noumena". So on what grounds does Kant posit the "in itself" from which he then conjures-up the "for us" to 'retro-construct' with various "transcendental" sleights-of-mind? — 180 Proof

It certainly seems Kant can be read that way: as "ontologizing epistemology"; the question would be whether that was his intention or whether it is an unconscious or unacknowledged entailment of his ideas. It's a good question, and I have to say I'm not sure. If I recall correctly there is in the world of Kant scholarship a controversy as to whether Kant's emprical/ transcendental dichotomy should be interpreted as a "dual aspect" or a "dual world" proposition.

Hopefully @Mww (and informed others) might comment. -

Mww

5.4kIt's an interesting question whether Kant's "in itself" denotes a reality — Janus

Mww

5.4kIt's an interesting question whether Kant's "in itself" denotes a reality — Janus

“…. The schema of reality is existence in a determined time….”

“…. For I can say only of a thing in itself that it exists without relation to the senses and experience….”

“…. we can have no cognition of an object, as a thing in itself, but only as an object of sensible intuition, that is, as phenomenon…”

Put them together, you get an affirmation that the thing in itself denotes an existence in a determined time.

controversy as to whether Kant's emprical/ transcendental dichotomy should be interpreted as a "dual aspect" or a "dual world" proposition. — Janus

If there is no direct knowledge of the world, but only of its representations, there is no need for a dual world. There is one world affecting the senses, half of a dual aspect, and the system by which it is understood, the other half.

Lots between the lines in all that, if you’re inclined to dig it out. -

Janus

18kI'll try to "dig it out":

Janus

18kI'll try to "dig it out":

“…. The schema of reality is existence in a determined time….”

“…. For I can say only of a thing in itself that it exists without relation to the senses and experience….”

“…. we can have no cognition of an object, as a thing in itself, but only as an object of sensible intuition, that is, as phenomenon…”

Put them together, you get an affirmation that the thing in itself denotes an existence in a determined time. — Mww

If "the schema of reality is existence in a determined time" then that is referring to a reality for us; a collective representation, no?

If " a thing in itself [...] exists without relation to the senses and experience" then does it not follow that it is real and yet undetermined, or better, indeterminable?

If " we can have no cognition of an object, as a thing in itself, but only as an object of sensible intuition, that is, as phenomenon" then does it not follow that the object, or whatever it is that appears as an object, insofar as it exists "in itself" is real, even though unknown/ unknowable?

If there is no direct knowledge of the world, but only of its representations, there is no need for a dual world. There is one world affecting the senses, half of a dual aspect, and the system by which it is understood, the other half. — Mww

If there is just one world affecting the senses and the understanding, which are also part of that world, and yet "there is no direct knowledge of that world" where does that leave us? -

Mww

5.4k

Mww

5.4k

If #1…..not so sure a reality is a collective representation.

If #2…..real, and indeterminable.

If #3….that object which appears to us is determinable/knowable. The object in itself is the object as it doesn’t appear, hence is not determinable/knowable.

————-

where does that leave us? — Janus

With the hard problem of consciousness? -

Janus

18kI'm not an adherent, so not what I had in mind.

Janus

18kI'm not an adherent, so not what I had in mind.

If #1…..not so sure a reality is a collective representation.

If #2…..real, and indeterminable.

If #3….that object which appears to us is determinable/knowable. The object in itself is the object as it doesn’t appear, hence is not determinable/knowable.

————- — Mww

#1: "The world (reality) is the totality of facts..." what is a fact if not a collective representation?

#2&3: You agree the object in itself is transcendental (to experience) and real...so why not Transcendental Realism...? -

Wayfarer

26.2kIt's a mistake to say in respect of the opposition of materialism and idealism, that they are somehow equivalent or that they are two horns of a dilemma - where materialists say that 'everything is composed of matter', idealists say that 'it's composed of mind'. It's far less simple than that.

Wayfarer

26.2kIt's a mistake to say in respect of the opposition of materialism and idealism, that they are somehow equivalent or that they are two horns of a dilemma - where materialists say that 'everything is composed of matter', idealists say that 'it's composed of mind'. It's far less simple than that.

Materialism takes many forms - as does idealism - but it must rely on there being some ultimately real object or thing, which comprises the basic constituent of all other things. (Of course, this simple picture has been considerably muddied by modern physics, but that's a whole other issue.)

Idealism, on the other hand, does not necessarily posit 'the mind' as an ultimate constituent in that sense; mind is not necessarily understood as 'a constituent' or a 'building block' in the way that, say, Lucretius' atoms were. So it's not a matter of one side saying that 'matter' is the ultimate constituent, and the other side insisting that 'mind' must be (although there are some idealists who will, but I'm leaving them aside.)

Rather idealism is saying that, whatever you say is the 'ultimate constituent of reality', that will always occur to you as an appearance, or as a consistent sensory experience - tables are consistently tables, this experiment always produces that result, and so on. It will then point out that whatever you claim is an ultimate constituent or object, can be nothing other than a consistent form of experience, something that appears invariant through time in your experience of the world. And that's not to deny the reality of such experiences - they're repeatable, governed by laws, observable by third parties, and so on. But they're all ultimately experiential in nature, rather than ultimately material in nature. So what that undercuts is the idea, not of material entities, but of their mind-independence. That's what I take idealism to be saying.

I will add that the picture of mind and body being two equal-but-opposing kinds of stuff originates fairly and squarely with Descartes, and is responsible for many of the plights of the modern condition. -

Isaac

10.3kIt will then point out that whatever you claim is an ultimate constituent or object, can be nothing other than a consistent form of experience, something that appears invariant through time in your experience of the world. And that's not to deny the reality of such experiences - they're repeatable, governed by laws, observable by third parties, and so on. But they're all ultimately experiential in nature, that than ultimately material in nature. — Wayfarer

Isaac

10.3kIt will then point out that whatever you claim is an ultimate constituent or object, can be nothing other than a consistent form of experience, something that appears invariant through time in your experience of the world. And that's not to deny the reality of such experiences - they're repeatable, governed by laws, observable by third parties, and so on. But they're all ultimately experiential in nature, that than ultimately material in nature. — Wayfarer

I think the mistake here is to confuse that which is being posited with the justification for doing so. Had I only ever seen teacups, I might reasonably conclude the world was composed entirely of teacups. What I'm positing is an external world made of teacups. My reasons for doing so are that my experiences (my personal world) consists entirely of teacups, and so it seems reasonable.

Materialists are not denying their experiences form the source of their conjecture. They're simply taking the fairly parsimonious position that "if our experiences are all pretty consistently like this, then maybe that's because the world is constituted that way"

The latter is the hypothesis, the experiences are the evidence/justification. -

Isaac

10.3khow does it show that the elements of experience have any ultimate material constituent? — Wayfarer

Isaac

10.3khow does it show that the elements of experience have any ultimate material constituent? — Wayfarer

I don't think it does (though doubtless some materialists do). It's a conjecture. A hypothesis to explain how things seem to be. It has against it the complexities of quantum physics, but it has in it's favour the compelling parsimony that that's exactly how things do seem to be.

I don't think the old-fashioned notion of actual atomism is defensible any more in the light of modern physics (though maybe string theory? I get very lost in physics), but 'materialism' sensu lato, is more about externality than 'matter'. -

Michael

16.8kMaterialism takes many forms - as does idealism - but it must rely on there being some ultimately real object or thing, which comprises the basic constituent of all other things. — Wayfarer

Michael

16.8kMaterialism takes many forms - as does idealism - but it must rely on there being some ultimately real object or thing, which comprises the basic constituent of all other things. — Wayfarer

That strikes me as atomism, not materialism. String theory is perhaps an example of atomistic materialism, but the Standard Model is perhaps an example of non-atomistic materialism. -

Mww

5.4kYou agree the object in itself is transcendental (to experience) and real….so why not transcendental realism? — Janus

Mww

5.4kYou agree the object in itself is transcendental (to experience) and real….so why not transcendental realism? — Janus

I suppose transcendental to experience just means has nothing to do with it. Transcendental merely indicates a method of reason, and is always a priori, so I’d agree the thing in itself has nothing to do with experience. Took me awhile to sort that out, and I’m still not sure if I read you correctly.

As to why not transcendental realism, is the assignment of a mere conception alone to validate a physical object, and as we all know, conception alone is in no way sufficient for empirical knowledge. On the other hand, the fact of perception makes explicit the reality necessary for its cause, which makes the thing in itself a necessary antecedent condition, even if nothing can be known of it in itself, insofar as it is the representation only, of the thing in itself, that is.

So….here we go.

There are established philosophies in which is found a mix of Kantian transcendental conceptions adjoined to real objects, re: Berkeley and successor dogmatic idealists, the ground of which is the attribution of Kantian transcendental conceptions of space and time as properties adhering in objects.

(The granting of singular space and time to an object, as opposed to the relation of object to space and time generally. This thing is right here, right now, therefore a space and a time belong to any object right here right now)

For those who think thus, a form of realism in which space and time are properties belonging to objects, they wouldn’t thereby consider themselves transcendental realists, insofar as, transcendentally, in Kant, space and time are two conceptions embracing the infinite, yet having no intrinsic substance belonging to them, the seriously contradictory results of that being quite obvious.

1.) If space and time are infinite, it is impossible to even think, must less determine, which space and which time belongs to a particular object immediately appearing to our senses.

2.) If a space and a time belong to an object, it is impossible to explain motion and duration, without claiming the space and time follow the object because it is a property belonging to it. But if that is the reality, it needs be said what fills the void left by change of position and change in successive durations of such object. While empty space is conceivable as having no object in it, it is impossible to conceive of no space at all, which must be admitted if a moving object includes its own space.

(Sidebar: back in my higher education days, in the theory of electron movement….electrons go this way, holes go the opposite way, insofar as a moving electron leaves a hole where it was. But this, just as for space and time, can be a misappropriated conceptual device)

3.) Without the possibility of determining which space and which time, of the infinite manifold of each, belongs to an object, it is impossible to prove that one and only one object can have that one singular spatial property and it is impossible to prove that an object can exhibit the very same existence in a succession of times. Before thinking this is preposterous, reflect on Feynman positing that if it is impossible to determine which path the particle takes through the slit, we must admit it took all of them., a.k.a., “sum over histories” hypothetical premise. And with that initial premise, is given the starting point for demonstrations otherwise.

So there may be a realism in which space and time are properties belonging to objects, but it is impossible for those holding with it to be transcendental realists in a Kantian sense. And if it be granted Kant defines transcendental philosophy, then the notion of transcendental realism itself, is refuted, from which follows necessarily, that those holding with it, have misunderstood the world.

For transcendental realism to be a valid doctrine, the concept of transcendental itself, and all that follows from it, must be conceived quite differently.

————

I'm not an adherent, so not what I had in mind. — Janus

Not an adherent taken to mean regarding the hard problem…..hence my question mark. So did you have something else in mind, as to where we are left when it is the case there is one world but for which we cannot have direct, unmediated knowledge? -

Banno

30.6k, , this one:

Banno

30.6k, , this one:

Idealism and the Mind-Body Problem

's schema does not quite capture the full depth and breadth of idealist thinking...

The salient point being that we might all agree with David Chalmers' conclusion. Anyone who pretends to having the answer to the mind-body problem is having a lend. But in addition, any discussion of idealism and realism will flail about unless some clarity is enforced on what is being discussed.

There was a brief period in which the realism/anti-realism discussion made some small progress, now perhaps only historical.

But rehashing Kant, yet again, ain't going to cut it. -

Janus

18kThanks, there's a lot there and I don't have much time today, so just one clarifying question:

Janus

18kThanks, there's a lot there and I don't have much time today, so just one clarifying question:

Do you take 'transcendental' to mean beyond experience, unknowable?

And a response that hopefully will make my idea clearer:

As to why not transcendental realism, is the assignment of a mere conception alone to validate a physical object, and as we all know, conception alone is in no way sufficient for empirical knowledge. On the other hand, the fact of perception makes explicit the reality necessary for its cause, which makes the thing in itself a necessary antecedent condition, even if nothing can be known of it in itself, insofar as it is the representation only, of the thing in itself, that is. — Mww

Right, so we cannot be talking about empirical knowledge of the transcendental as it is in-itself. Empirical knowledge can only be knowledge of the in-itself as it is represented by us. Empirical knowledge is suffused with ideas; that's why I say it is ideal. We don't know whether how we represent what is given to us via the senses in any way reflects or corresponds to an independent reality, or what that could even mean.

All we know is that we think there must be such a reality, a transcendental (because unknowable-as-it-is-in-itself reality), but a reality nonetheless, so that is why I say transcendental realism seems to logically follow. But again that is not an empirically established conclusion (other than that our perceptual representations seems to be consistent enough for us to stay out of trouble most of the time, which suggests that our senses are representing the noumenal accurately enough for practical purposes). It is, rather, an inference to the best explanation.

This from the Chalmers paper seems to support my interpretation of Kant:

Kant’s transcendental idealism is not really a version of idealism in the metaphysical sense I am concerned with here. It is sometimes called a version of epistemological idealism: at most it is idealist about the knowable phenomenal realm but not the unknowable noumenal realm, so it is not idealist about reality in general.

Welcome to The Philosophy Forum!

Get involved in philosophical discussions about knowledge, truth, language, consciousness, science, politics, religion, logic and mathematics, art, history, and lots more. No ads, no clutter, and very little agreement — just fascinating conversations.

Categories

- Guest category

- Phil. Writing Challenge - June 2025

- The Lounge

- General Philosophy

- Metaphysics & Epistemology

- Philosophy of Mind

- Ethics

- Political Philosophy

- Philosophy of Art

- Logic & Philosophy of Mathematics

- Philosophy of Religion

- Philosophy of Science

- Philosophy of Language

- Interesting Stuff

- Politics and Current Affairs

- Humanities and Social Sciences

- Science and Technology

- Non-English Discussion

- German Discussion

- Spanish Discussion

- Learning Centre

- Resources

- Books and Papers

- Reading groups

- Questions

- Guest Speakers

- David Pearce

- Massimo Pigliucci

- Debates

- Debate Proposals

- Debate Discussion

- Feedback

- Article submissions

- About TPF

- Help

More Discussions

- Other sites we like

- Social media

- Terms of Service

- Sign In

- Created with PlushForums

- © 2026 The Philosophy Forum