-

Gus Lamarch

924[The dissertation below defends the philosophical-psychological hypothesis of the evolution, in the last six thousand years, of the human mind, from a Bicameral to a Unicameral consciousness, through the structuring of society, and its existence in the early periods of human history]

Gus Lamarch

924[The dissertation below defends the philosophical-psychological hypothesis of the evolution, in the last six thousand years, of the human mind, from a Bicameral to a Unicameral consciousness, through the structuring of society, and its existence in the early periods of human history]

[This is a discussion focused solely and exclusively on the human mind, regardless of the psyche of the rest of the animal kingdom]

[The following analysis and its conclusions may be of difficult understanding for certain readers without an average knowledge of history, psychology, and philosophy, therefore, it is necessary that the reading be carried out with patience and diligence so that it is easily digested]

First Topic: The Search for the Human Consciousness

The discussion of what substantiates the human mind and its consciousness, is a question that has been sought for the answer for more than 2,000 years, having been addressed even by the classical Greeks, such as Isocrates - 436 BC to 338 BC - who saw the spirit - pneuma - as if existing in humanity, through the internal and external rhetorical expression of feelings, logic and imagination - therefore, rhetoric would be the substance of the human intellect - or as Plato would establish, that "the intellect of Man is an infinite extension between the ideal metaphysical and the physical material worlds, who would be aware of himself and his finitude as well as of his absolute existence in the world of ideas".

The perception of conscience as something immaterial and essentially transcendental would remain the norm for more than 1600 years, until, with the intellectual revolutions of the centuries permeated by the Enlightenment, a new path that could answer the question of conscience had been discovered, which is made concrete for its foundation in research and historical-rational evidentiality.

In fact, Western philosophers since the time of Descartes and Locke have struggled to comprehend the nature of consciousness and how it fits into a larger picture of the world. One of the primary conceptions of the perception of "the body's interdependent existence with the mind" had been established by the dualistic view.

The dualistic perception of the relationship between the body and the mind was first established by Descartes - 1596 AD to 1650 AD - with his "Cartesian Dualism" in which he argued that "the mind is a nonphysical — and therefore, non-spatial — substance".

It is interesting to realize that, every inquiry about the human mind until Descartes, was conceived as completely metaphysical, without any connection or interaction with the physical - brain - body. It is with Descartes that, for the first time in history, through rational intuition, we have the hypothesis of the intrinsic interaction of a part of the body - in his - Descartes's - case, the pineal gland - for the expression and projection of consciousness.

As Gert-Jan Lokhorst, in his article, "Descartes and the Pineal Gland" states:

"He was the first to suggest that the interaction between these two domains - mind and body - occurs inside the brain, he hypothesized that perhaps this occured in a small midline structure called the pineal gland. Refuted or not, the fact is that it was with his intuition that the contemporary quest for consciousness began."

With the rational view established, several other thinkers, psychologists and philosophers put themselves at the forefront of the duty to seek the answer to consciousness, and several decided to seek this conclusion in history; more precisely, in ancient human history.

Second Topic: The Historical-Evolutionary View

Entering the 20th century, already having the historical and archaeological record of the distant past, commonly known as the "Bronze Age", and its societies, many sought to study through history, how consciousness could have arisen in humanity. One of the pioneers in this field was Julian Jaynes - 1920 to 1997 - who spent 25 years of his academic career studying the development of human consciousness, which, within the archaeological and historical records of the ancient period, seemed to resemble another type of aspect of "consciousness" other than the one pre-established by the evolutionary vision of its time - which categorized "conciousness" as simply "awareness" -.

As Jaynes would state in his book, "The Origin of Consciousness in the Breakdown of the Bicameral Mind":

"This search took me to the earliest writings of mankind to see if we can find any hints as to when this important invention of "consciousness" might have occurred. I went to ancient texts searching for early evidence of consciousness, and found what I believed to be evidence of remarkably recent voice-hearing without consciousness."

In his studies of the classic epic of the "Iliad", when assessing the linguistics of the individual perceptions of its characters and their allegories regarding the introspective nature of the existence of the Archaic Greeks, Jaynes would state:

"In the semi-historical Greek epic "The Iliad", the earliest writing of men in a language that we can really comprehend, when looked at objectively, reveals a very different mentality from our own.”

Through the following conclusion, Jaynes set out to describe the theory of how consciousness was born out of the end of the Bicameral mind:

- Humanity, until the period of the first historical manuscripts, does not present in any form a conception of the understanding of conscience - introspectiveness, which has the capacity to "think about itself -;

- We cannot access and study the habits and psychological functionalities of the ancients in first instance - from 700 BC to 6000 BC - to prove through evidence that they had the mental and conceptual structure that humans post-500 BC, however, there is historical-archeological evidence that strengthens the contrary notion;

- Therefore, the ancient human conscience was not necessarily identical to the current one.

The Bicameral theory of mind would therefore be established.

Third Topic: The Origin of Consciousness in the Breakdown of the Bicameral Mind

In his theory, Jaynes goes on to explain consciousness, “the human ability to introspect”. Abandoning the assumption that consciousness is innate, Jaynes explains it instead as a learned behavior that “arises from language, and specifically from metaphor”.

With this understanding, Jaynes then demonstrated that ancient texts and archeology can reveal a history of human mentality alongside the histories of other cultural products. His analysis of the evidence led him not only to place the origin of consciousness during the 2nd millennium BC but also to hypothesize the existence of an older non-conscious mentality that he called the "bicameral mind", referring to the brain’s two hemispheres.

In the third chapter of the book, "The Mind of the Iliad", Jaynes states that people of the era - Bronze Age - Ancient Era - - had no consciousness:

"There is in general no consciousness in the Iliad. I am saying "in general" because I shall mention some exceptions later. And in general therefore, no words for consciousness or mental acts. The words in the Iliad that in a later age come to mean mental things have different meanings, all of them more concrete. The word psyche, which later means soul or conscious mind, is in most instances life-substances, such as blood or breath: a dying warrior bleeds out his psyche onto the ground or breathes it out in his last gasp. The thumos, which later comes to mean something like emotional soul, is simply motion or agitation. When a man stops moving, the thumos leaves his limbs. But it is also somehow like an organ itself, for when Glaucus prays to Apollo to alleviate his pain and to give him strength to help his friend Sarpedon, Apollo hears his prayer and “casts strength in his thumos”. The thumos can tell a man to eat, drink, or fight."

"Bicameral" mentality would be non-conscious in its inability to reason and articulate about mental contents through "meta-reflection", reacting without explicitly realizing and without the meta-reflective ability to give an account of why one did so.

The bicameral mind would thus lack metaconsciousness, autobiographical memory, and the capacity for executive "ego functions" such as deliberate mind-wandering and conscious introspection of mental content. When bicamerality as a method of social control was no longer adaptive in complex civilizations - as in the Bronze Age Collapse -, this mental model was replaced by the conscious mode of thought which, Jaynes argued, is grounded in the acquisition of metaphorical language learned by exposure to narrative practice.

Ancient people in the bicameral state of mind would have experienced the world in a manner that has some similarities to that of a person with schizophrenia. Rather than making conscious evaluations in novel or unexpected situations, the person would hallucinate a voice or "god" giving admonitory advice or commands and obey without question.

The perception is that, humanity, until that point, without the scientific, social-political, moral and ethic perception of reality, would see their own "counsciouness" - the voice, aka, the introspectiveness of the subjective - as being the hallucinating voice of the Gods, as until then, mythology was seen as the principle that made reality "real".

The bicameral individual was guided by mental commands believed to be issued by external "gods" who told commands which were recorded in ancient myths, legends and historical accounts.

As Jaynes affirms:

"In ancient times, gods were generally much more numerous and much more anthropomorphic than in modern times, this was because each bicameral person had their own "god" who reflected their own desires and experiences."

Such a mentality is not seen in today's humanity, and the cause can also be found in the study of history.

Fourth Topic: Breakdown of Bicameralism

Jaynes theorized that a shift from bicameralism marked the beginning of introspection and consciousness as we know it today. This bicameral mentality began malfunctioning or "breaking down" during the 2nd millennium BC. He speculates that primitive ancient societies tended to collapse periodically, for example, Egypt's "Intermediate Periods", as well as the periodically vanishing cities of the Mayas, as changes in the environment strained the socio-cultural equilibria sustained by this bicameral mindset.

The Bronze age collapse of the 2nd millennium BC led to mass migrations and created a rash of unexpected situations and stresses which required ancient minds to become more flexible and creative. "Self-awareness", or "consciousness", was the culturally evolved solution to this problem.

This necessity of communicating commonly observed phenomena among individuals who shared no common language or cultural upbringing encouraged those communities to become self-aware to survive in a new environment. Thus consciousness, like bicamerality, emerged as a neurological adaptation to social complexity in a changing world.

In Jaynes words:

"When the world ended, and when the Gods stopped talking to us, in a sense, we made ourselves our own Gods."

Fifth Topic: The Evidence in the Dawn of Society

Having clarified all the points necessary to understand my arguments and my statements, it remains to present the evidence to you.

In addition to the evidence Jaynes demonstrates in his book, using the periods from 2000 BC to 700 BC, I believe that a greater and more substantial evidence about the bicamerality of the mind can be found, however, in a much older period; at the birth of society, more precisely, at the foundation of its first "city" - Uruk.

The Uruk period - 4000 to 3100 BC - existed from the protohistoric "Chalcolithic" to the "Early Bronze Age" period in the history of Mesopotamia, after the "Ubaid" period and before the "Jemdet Nasr" period. Named after the Sumerian city of Uruk, this period saw the emergence of urban life in Mesopotamia and the Sumerian civilization.

On the cusp of prehistory and history, the Uruk period can be considered "revolutionary" and foundational in many ways. Many of the innovations which it produced were turning points in the history of Mesopotamia and indeed of the world.

It is in this period that one sees the general appearance of the potter's wheel, writing, the city, and the state. There is new progress in the development of state-societies, such that specialists see fit to label them as "complex" - in comparison with earlier societies which are said to be "simple" -.

This period is, therefore, as a crucial step in the evolution of society, a long and cumulative process whose roots could be seen at the beginning of the Neolithic more than 6000 years earlier and which had picked up steam in the preceding Ubaid period in Mesopotamia.

The 4th millennium saw the appearance of new tools which had a substantial impact on the societies that used them, especially in the economic sphere.

Some of them, although known in the preceding period, only came into use on a large scale at this time. The use of these inventions produced economic and social changes in combination with the emergence of political structures and administrative states.

In the agricultural sphere, several important innovations were made between the end of the Ubaid period and the Uruk period, which have been referred to in total as the "Second Agricultural Revolution" - the first being the Neolithic Revolution -. A first group of developments took place in the field of cereal cultivation, followed by the invention of the ard - a wooden plough pulled by an animal - towards the end of the 4th millennium BC, which enabled the production of long furrows in the earth. This made the agricultural work in the sowing season much simpler than previously, when this work had to be done by hand with tools like the hoe.

The development of woolworking, which increasingly replaced linen in the production of textiles, had important economic implications. Beyond the expansion of sheep farming, these were notably in the institutional framework, which led to changes in agricultural practice with the introduction of pasturage for these animals in the fields, as convertible husbandry, and in the hilly and mountainous zones around Mesopotamia - following a kind of transhumance -.

In architecture, the developments of the Uruk period were also considerable. The builders perfected the use of molded mud-brick as a building material and the use of more solid terracotta bricks became widespread. They also began to waterproof the bricks with bitumen and to use gypsum as mortar.

New types of decoration came into use, like the use of painted pottery cones to make mosaics, which are characteristic of the Eanna in Uruk, semi-engaged columns, and fastening studs.

The Uruk period provides the earliest signs of the existence of states in the Near East. What kind of political organisation existed in the Uruk period is debated. No evidence supports the idea that this period saw the development of a kind of "proto-empire" centred on Uruk, as has been proposed by some historians. It is probably best to understand an organisation in "city-states" like those that existed in the 3rd millennium BC.

It is clear that there were major changes in the political organisation of society in this period.

It is visible the complexity already pre-established by humanity in its most primitive periods, which comprised several aspects of what is now also understood as "society".

However, even though a civilization has been developed that borders on the administrative and bureaucratic complexity of contemporary society, with its intrinsic needs for economic, theological, historical and administrative records, at no time, tablet, inscription, tomb, memorial, etc... is described in any way, the individual introspective perception of the self-conscious mind. However, we have thousands and thousands of references to "divine prophecies", "sacred commands", "words of Gods", which are projected to the smallest detail.

In Conclusion:

In a comparative analysis of both evidential historical contexts - the lack of evidence to the perception of individual conscience and the large amount of evidence of the lack of individual conscience on ancient times - together with the analysis of the societal archeological context of the time, the following statement can be made:

"Humanity, in a hypothetical scenario where its mind would be structured bicamerally, would still be able to develop a society as complex and bureaucratic as that structured by unicameral humanity."

Therefore, the following affirmation is correct:

"For the historical evidence of the lack of citations on the subjectivity of the introspectivity of human consciousness, and for the vast amount of evidence that supports the hypothesis of an ancient bicameral humanity, the most substantial scenario in history is that of the Bicamerality of the Mind."

And therefore, the first civilization - Sumer - had been developed and composed by bicameral individuals. -

Wayfarer

26.1kVery interesting article, thank you. I think it is certainly true that different eras give rise to completely different forms of consciousness.

Wayfarer

26.1kVery interesting article, thank you. I think it is certainly true that different eras give rise to completely different forms of consciousness.

A couple of footnotes:

the mind is a nonphysical — and therefore, non-spatial — substance". — Gus Lamarch

'The philosophical term ‘substance’ corresponds to the Greek ousia, which means ‘being’, transmitted via the Latin substantia, which means ‘something that stands under or grounds things’. According to the generic sense, therefore, the substances in a given philosophical system are those that, according to the system, are the foundational or fundamental entities of reality.' ~ SEP

I say this because of the common misconception of Descartes' 'res cogitans' as 'spooky stuff' due to the equivocation with the ordinary use of the word 'substance' which means 'a material with uniform properties'.

"[Descartes] was the first to suggest that the interaction between these two domains - mind and body - occurs inside the brain, he hypothesized that perhaps this occured in a small midline structure called the pineal gland. Refuted or not, the fact is that it was with his intuition that the contemporary quest for consciousness began." — Gus Lamarch

Descartes' model also gives rise to the mind-body problem that characterises modern thought, generally:

The modern mind-body problem arose out of the scientific revolution of the seventeenth century, as a direct result of the concept of objective physical reality that drove that revolution. Galileo and Descartes made the crucial conceptual division by proposing that physical science should provide a mathematically precise quantitative description of an external reality extended in space and time, a description limited to spatiotemporal primary qualities such as shape, size, and motion, and to laws governing the relations among them. Subjective appearances, on the other hand -- how this physical world appears to human perception -- were assigned to the mind, and the secondary qualities like color, sound, and smell were to be analyzed relationally, in terms of the power of physical things, acting on the senses, to produce those appearances in the minds of observers. It was essential to leave out, or subtract, subjective appearances and the human mind -- as well as human intentions and purposes -- from the physical world in order to permit this powerful but austere spatiotemporal conception of objective physical reality to develop. — Thomas Nagel, Mind & Cosmos, Pp 35-36

As no account of how 'the mind' interacts with 'matter' ever was developed, this has left rather a large hole in the model, whereby Descartes' notion of 'spirit' was to be dismissed as a 'ghost in the machine'.

Also - it's interesting to compare a book called Shakespeare and the Invention of the Human, Howard Bloom, which claims that Shakespeare's famous plays, particularly Hamlet and Macbeth, essentially gave birth of the modern idea of the human person.

I've also encountered a book which claims that Augustine singlehandedly devised the idea of the 'inner self' - https://www.amazon.com/dp/019515861X/r - likewise a kind of milestone in the history of the self (Augustine is often regarded as the most influential Christian after Paul the Apostle.) -

Jack Cummins

5.7kI believe that it is a good idea to start a thread based on the ideas of Julian Jaynes. His work gets mentioned occasionally on various threads, but have never been explored fully and do have profound implications for the understanding of the emergence of human consciousness historically. I like your summary of his ideas because I didn't get a chance to write down the ideas when I read the book.

Jack Cummins

5.7kI believe that it is a good idea to start a thread based on the ideas of Julian Jaynes. His work gets mentioned occasionally on various threads, but have never been explored fully and do have profound implications for the understanding of the emergence of human consciousness historically. I like your summary of his ideas because I didn't get a chance to write down the ideas when I read the book.

Aside from the implications for understanding human consciousness, the ideas of Jaynes do present a challenge to the medical model of psychosis, especially schizophrenia. However, I am not sure if you are interested in that area. It was in that context that I came across Jaynes' ideas. It was a patient in the acute psychiatric admissions ward I was working on who introduced me to it. The particular patient was enthralled with it, but most of the staff seemed to think that it was ridiculous, and they seemed baffled by my long discussion of it with the patient himself. While the staff on the ward I was working with were dismissive of the whole idea of the bicameral mind, I do wonder how psychiatrists view Jaynes' work generally. -

Pfhorrest

4.6kI thought it was very cool when the HBO show "Westworld" incorporated the concept of a bicameral mind into their depiction of artificial intelligence achieving true self-awareness: that being when one realizes that the voice in their head telling them what to do is their own voice, not something outside of themselves.

Pfhorrest

4.6kI thought it was very cool when the HBO show "Westworld" incorporated the concept of a bicameral mind into their depiction of artificial intelligence achieving true self-awareness: that being when one realizes that the voice in their head telling them what to do is their own voice, not something outside of themselves.

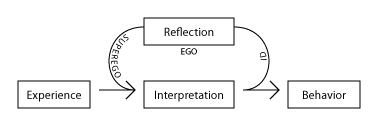

I just wrote something on a similar topic in my latest thread, though I relate it more to Freud's id, ego, and superego there, more of a "tricameral" mind; but I could see how that phenomenal appearance of three-part-ness could be implemented in a two-part brain:

...None of this is yet sufficient to call something free will in our ordinary sense of the word. For that, we need all of the above plus also another function, a reflexive function that turns that sentient intelligence back upon the being in question itself, and forms perceptions and desires about its own process of interpreting experiences, and then acts upon itself to critique and judge itself and then filter the conclusions it has come to, accepting or rejecting them as either soundly concluded or not. That reflexive function in general I call "sapience", and the aspect of it concerned with critiquing and judging and filtering desires I call "will" proper.

(I see the concepts of "id", "ego", and "superego" as put forward by Sigmund Freud arising out of this reflexive judgement as well, with the third-person view of oneself that one is casting judgement upon being the "id", the third-person view of oneself casting judgement down on one being the "superego", and the first-person view of oneself, being judged by the superego while in turn judging the id, being the "ego"; an illusory tripartite self, as though in a mental hall of mirrors). — Pfhorrest

-

bongo fury

1.8kWe all talk to ourselves from time to time — jgill

bongo fury

1.8kWe all talk to ourselves from time to time — jgill

Might the comic possibilities of that line maybe explain our willingness to indulge such a brilliantly bonkers theory?

Language gave us imagination, but a deep confusion about it, too. Witness our precarious and probably dangerous modern pathologising of "hearing voices".

I'd buy (and for a long while tried to) the hypothesis of "godlike instructions", if only I could believe that humans haven't always and ever been inwardly rehearsing clever things to say to each other. (And the likely replies.) -

Ciceronianus

3.1kInteresting, but unpersuasive.

Ciceronianus

3.1kInteresting, but unpersuasive.

Polytheism and anthropomorphic gods remained quite popular in the West at least until Christianity began stamping the gods out so relentlessly commencing in the 4th century C.E., and may be said to have survived for quite some time after that in the cult of the saints. Also, the belief in the divinity of Jesus requires an anthropomorphic view of God, which theologians have strived to cover over, unsuccessfully I would say, for centuries by attempting to incorporate into Christianity the "god of the philosophers."

Perhaps our ancestors in Sumer and elsewhere were too busy with other things to ponder human consciousness. For good or ill, its seems that we have more (too much?) time on our hands -

simeonz

310

simeonz

310

I was trying to get off the forum , but this thread brought me to ask for a few clarifications.

Does the above statement imply that the solipsistic question of other people's experience of the mind is meaningless, or is this categorically different question? Jaynes, as a researcher, may not have had interest in such riddle at all, but does he operate under the premise that inquiries about the metaphysics of the mind are meaningless, or are they simply not in the purview his interests?In his theory, Jaynes goes on to explain consciousness, “the human ability to introspect”. Abandoning the assumption that consciousness is innate, Jaynes explains it instead as a learned behavior that “arises from language, and specifically from metaphor”. — Gus Lamarch

From a brief survey of the topic on Wikipedia. I was surprised that the lateralization of the brain is conjectured to not only encompass creativity and learning, but also the self and others. Very enlightening. Part of the criticism appears to be around the dating of an early literary work, the "Epic of Gigamesh". I wouldn't know either way and I can't judge on that alone. What seemed more justifiably concerning however, was that proliferation and cultural penetration of genetics was very unlikely to happen in just centuries, if I am not misunderstanding the implied timeline. Lactose tolerance/persistence started at about the same time, even earlier, and we are still observing significant amount of intolerant people unevenly distributed around the globe's continents. If this theory is suggesting a new genetic allele, it is either suggesting that it was dominant or that it was highly advantageous, or that not all of us have the ability developed in this regard? If idea was elaborated in terms of graduations, it would allow some people to develop lower IQ for this reason, but if we are talking about one spontaneous mutation, I would expect some non-negligible part of the population would still continue to be unaware of their intents and function like animal species.- Humanity, until the period of the first historical manuscripts, does not present in any form a conception of the understanding of conscience - introspectiveness, which has the capacity to "think about itself -;

- We cannot access and study the habits and psychological functionalities of the ancients in first instance - from 700 BC to 6000 BC - to prove through evidence that they had the mental and conceptual structure that humans post-500 BC, however, there is historical-archeological evidence that strengthens the contrary notion;

- Therefore, the ancient human conscience was not necessarily identical to the current one. — Gus Lamarch

Does that give them some kind of substitute cognitive loop, without explicit self-referentiality, or was it incomparably limiting experience? Just to be clear about the distinguishing cognitive aspect - I surmise that we are talking about lack of acknowledged mental agency, not merely lack of auto-psychological skill. I assume that those people did probably understand involvement in situations, just not involvement in mental judgements, if I interpreted the conjecture correctly.Ancient people in the bicameral state of mind would have experienced the world in a manner that has some similarities to that of a person with schizophrenia. Rather than making conscious evaluations in novel or unexpected situations, the person would hallucinate a voice or "god" giving admonitory advice or commands and obey without question. — Gus Lamarch

It is reasonably convincing argument, from my uneducated point of view, but personally, it remains a conjecture. It seems probable, maybe could be factual. Looking from the sidelines, I would like more scientific consensus to inspire my confidence and to have more details about the cognitive effects, and the chronological account elaborated. You deem this theory accurate through process of elimination, but this is finicky practice, even if necessary, for lack of proper historical account.

P.S. Thanks. For the interesting and conscientiously presented work. -

Gnomon

4.3k

Gnomon

4.3k

When I fist heard of Jayne's hypothesis, I thought the notion of a bicameral brain -- to explain the emergence of human-type consciousness -- was a good literary or historical metaphor, if not a scientific thesis, based on hard evidence. Unfortunately, it seems that neuroscience has not taken it very seriously. That may be because their emphasis is on the physical substrate of the mind (neurons), rather than the spiritual Cartesian res cogitans. As you said, "the mind is a nonphysical — and therefore, non-spatial — substance". If so, it might not be limited to physical spatial boundaries. Which sounds spooky to pragmatic scientists, because it might also be able to transcend the individual's brain & body. However, I assume that the conscious & subconscious Mind is not a ghostly Spirit, but merely a brain Function : Mind is a name for what the brain does -- thinking, feeling, etc.invention of "consciousness" — Gus Lamarch

Freud may have intuitively referred to the bicameral nature of the mind in his metaphors of Id, Ego, and Superego. In that case, the "Super-ego" might refer to the role of the dominant "conscious" chamber of the brain. But, I still doubt that General Consciousness is limited to one hemisphere. The creative-emotional "language" of the right brain seems to be a non-verbal form of conscious awareness. But only the left brain can make itself known to other minds via language. Lacking the words to express its visions and urges, schizophrenics may appear to be motivated by external demons, rather than conflicting inner emotions or drives.

Some scientists think consciousness is directly related to language. Hence, dependent on the typically “dominant”, “rational” and verbal left-brain. But that could be due to their bias toward rational thinking, and distrust of irrational motives. But both "fast" Right Brain & "slow" Left Brain modes of thinking are normal for humans. However sub-conscious thoughts & feelings are mostly concerned with emotional functions. In that case, the commanding "voices" & visions might be merely non-verbal automatic reflex urges & feelings (i.e. "Fast" thinking).

Split-brain experiments seem to result in two minds in one body, But that's difficult to parse into an understandable model of general consciousness, which might explain how the "bicameral mind" could present a consistent singular.personality . It's possible that a study of close relations to humans, e.g. chimpanzees & bonobos, could shed some light on Jayne's notion of "pre-conscious" humans. If they are driven only by inner emotional urges, chimps might be equivalent to philosophical zombies, or robots. Their inner drives would not be experienced consciously, but more like encoded instructions, blindly converted into explainable actions. Has anyone done such a study, with a view toward a bicameral explanation? :chin:

Fast vs Slow Thinking : "System 1" is fast, instinctive and emotional; "System 2" is slower, more deliberative, and more logical.

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Thinking,_Fast_and_Slow

Right Brain, Left Brain: A Misnomer : A More Holistic Picture

https://dana.org/article/right-brain-left-brain-really/ -

Wayfarer

26.1kSome scientists think consciousness is directly related to language. Hence, dependent on the typically “dominant”, “rational” and verbal left-brain. — Gnomon

Wayfarer

26.1kSome scientists think consciousness is directly related to language. Hence, dependent on the typically “dominant”, “rational” and verbal left-brain. — Gnomon

Also worth knowing about Iain McGilchrist The Master and His Emissary: The Divided Brain and the Making of the Western World

McGilchrist presents a fascinating exploration of the differences between the brain’s left and right hemispheres, and how those differences have affected society, history, and culture. McGilchrist draws on a vast body of recent research in neuroscience and psychology to reveal that the difference is profound: the left hemisphere is detail oriented, while the right has greater breadth, flexibility, and generosity. McGilchrist then takes the reader on a journey through the history of Western culture, illustrating the tension between these two worlds as revealed in the thought and belief of thinkers and artists from Aeschylus to Magritte. -

Gnomon

4.3k

Gnomon

4.3k

The title Master & Emissary reminded me of Jonathan Haidt's interesting metaphor of the relationship between Conscious & Subconscious mind as the Mahout (rider) and his Elephant. That may not be what McGilchrist is referring to though.Some scientists think consciousness is directly related to language. Hence, dependent on the typically “dominant”, “rational” and verbal left-brain. — Gnomon

Also worth knowing about Iain McGilchrist — Wayfarer

Opinions on the book were polarized. Some reviewers focused on the poor quality of an $85 book, while others praised its focus on the whole brain, and others complained about its technical denseness and "verbal diarrhea", plus one described it as "for masochists only". Is it really that off-putting for those who don't buy his holistic view?

Jayne's notion of the "invention" of consciousness placed its emergence around the time of written language. But presumably un-written verbal language evolved long before written symbols began to replace or supplement untold millennia of communication via vocalizations along with hand & body gestures, as in chimps. Surely, some form of self-other consciousness accompanied those early forms of communication of inner concepts & feelings. Perhaps what coincided with complex social communities and written language was a more modern conception of self-consciousness and individualism. :smile:

Elephant & Rider :

https://www.jch.com/jch/notes/TheElephantAndTheRiderMetaphor.html -

Wayfarer

26.1kI watched a video interview with McGilchrist, he makes sense to me. Glad to see people of that stature exploring such ideas.

Wayfarer

26.1kI watched a video interview with McGilchrist, he makes sense to me. Glad to see people of that stature exploring such ideas.

Jayne's notion of the "invention" of consciousness placed its emergence around the time of written language. — Gnomon

There's an earlier book, not nearly so well-known in the academic mainstream, R M Bucke's Cosmic Consciousness. I liked that book better than Jayne's although it might derail the thread so I won't go into detail. (Some detail here.) But, I will say, I think the notion that Jayne's theory 'explains' the ancient Gods is a reductionist reading. My intuition is that in the ancient world, there was not nearly so strong a sense of 'I' and consequently humans had a more first-person relationship with the world at large - an 'I-thou' relation, rather than our 'I-it' sense. -

Jack Cummins

5.7k

Jack Cummins

5.7k

I was read Bucke's, 'Cosmic Consciousness' fairly recently and I think that it is a fascinating area for discussion, but similarly I would not wish to derail the thread. The whole area of debate opened up by Gus's exploration of the ideas of Jaynes and associates ones, opens up fascinating possibilities for discussion, but I imagine that we need to be patient to wait and see what direction he wishes the thread to take. I certainly would not wish to mess it up. -

Gregory

5kYe there was a theory among the counter culture in the 60's that says that ever since humans began to walk upright they have gotten less blood flow to the brain and that the relationship between the left and right bran has been disturbed in humans for many thousands of years. I don't know if there is any truth in this, but it was also alleged back then that the human skull is overly right in modern human adults and that this restricts the proper bloodflow to the two hemispheres of the brain. The "cure" that was offered back then was trepanning and acid, which I don't think is a good idea. I do wonder though if there is some truth to humans having an imbalance in their bicameral minds that results in confusion on issues of free will, the supernatural, and stuff like that.

Gregory

5kYe there was a theory among the counter culture in the 60's that says that ever since humans began to walk upright they have gotten less blood flow to the brain and that the relationship between the left and right bran has been disturbed in humans for many thousands of years. I don't know if there is any truth in this, but it was also alleged back then that the human skull is overly right in modern human adults and that this restricts the proper bloodflow to the two hemispheres of the brain. The "cure" that was offered back then was trepanning and acid, which I don't think is a good idea. I do wonder though if there is some truth to humans having an imbalance in their bicameral minds that results in confusion on issues of free will, the supernatural, and stuff like that. -

Gregory

5kJoey Mellen and Bart Huges were advocates of trepanning in the 60's They would make very small holes in peoples' skulls and people claimed it gave them a permanent high. The Beatles almost did it as a group but chickened out. I can blame them. It is true however that in modern medicine they take ou parts of the brain in people with very serious mental illness. A little hole to relieve pressure is nothing compared to that, but of course most people aren't seriously mentally ill

Gregory

5kJoey Mellen and Bart Huges were advocates of trepanning in the 60's They would make very small holes in peoples' skulls and people claimed it gave them a permanent high. The Beatles almost did it as a group but chickened out. I can blame them. It is true however that in modern medicine they take ou parts of the brain in people with very serious mental illness. A little hole to relieve pressure is nothing compared to that, but of course most people aren't seriously mentally ill -

Gregory

5k"Trepenning puts more blood in the brain. When you're born the plates of your skull aren't jioned together. When they are completely sealed it suppresses a pulsating in the brains arteries. The capillaries then shrink. You lose blood volute from the brain when you grow up. That is why children are 'higher' than grown-ups. It is the age that the plates seal- between eighteen and twenty- when people start to drink and take drugs in order to get high. They are trying to regain the consciousness they had as a child." Joey Mellen

Gregory

5k"Trepenning puts more blood in the brain. When you're born the plates of your skull aren't jioned together. When they are completely sealed it suppresses a pulsating in the brains arteries. The capillaries then shrink. You lose blood volute from the brain when you grow up. That is why children are 'higher' than grown-ups. It is the age that the plates seal- between eighteen and twenty- when people start to drink and take drugs in order to get high. They are trying to regain the consciousness they had as a child." Joey Mellen

The Extraction of the Stone of Madness is a famous painting by Hieronymus Bosch depicting trepanation -

Gus Lamarch

924Perhaps our ancestors in Sumer and elsewhere were too busy with other things to ponder human consciousness. For good or ill, its seems that we have more (too much?) time on our hands — Ciceronianus the White

Gus Lamarch

924Perhaps our ancestors in Sumer and elsewhere were too busy with other things to ponder human consciousness. For good or ill, its seems that we have more (too much?) time on our hands — Ciceronianus the White

The topic "The Evidence in the Dawn of Society" focuses explicitly on this point:

We have the most diverse archaeological, historical, anthropological and cultural records that Sumerian society had in a way that almost identifies to our society, a complexity that established the capacity of city-states, empires, and the bureaucratization of the economy and social-political stratification that still exists today, even without evidence that they had already evolved a "unicameral" consciousness capable of introspectively realizing, reflecting, and deciding on matters by themselves and not by the command of the "Gods".

They had plenty of time to spend with "abstract and metaphysical concepts", however, they did it through the misunderstanding of their own minds - aka, "Gods" -.

As I mentioned in my article:

"Rather than making conscious evaluations in novel or unexpected situations, the person would hallucinate a voice or" god "giving admonitory advice or commands and obey without question.

The perception is that, humanity, until that point, without the scientific, social-political, moral and ethic perception of reality, would see their own "counsciouness" - the voice, aka, the introspectiveness of the subjective - as being the hallucinating voice of the Gods, as until then, mythology was seen as the principle that made reality "real".

The bicameral individual was guided by mental commands believed to be issued by external "gods" who told commands which were recorded in ancient myths, legends and historical accounts." -

Gus Lamarch

924Does the above statement imply that the solipsistic question of other people's experience of the mind is meaningless, or is this categorically different question? Jaynes, as a researcher, may not have had interest in such riddle at all, but does he operate under the premise that inquiries about the metaphysics of the mind are meaningless, or are they simply not in the purview his interests? — simeonz

Gus Lamarch

924Does the above statement imply that the solipsistic question of other people's experience of the mind is meaningless, or is this categorically different question? Jaynes, as a researcher, may not have had interest in such riddle at all, but does he operate under the premise that inquiries about the metaphysics of the mind are meaningless, or are they simply not in the purview his interests? — simeonz

I believe that Jaynes, being a psychologist who based his hypotheses on the philosophy and historiography of the evolution of the human mind, would have no interest in the metaphysical questions of the arising of the mind.

The solipsist question is something that I believe to be intrinsically categorized within the field of study of metaphysics, which, if it is concluded that the mind is a social construction that has a biological effect, has no foundation.

In the aspect of the "physicality" of the mind, that is, that it is a product of the organic brain, I tend to disagree with Jaynes. Consciousness, if constructed by language and, consequently, by culture, is something that cannot be instrisically physical because the human mind is itself a construction that, within the animal kingdom, has no use for the simple and primitive objetctives of reproduction and survival of the species.

If the mind is a biological evolution of the adaptation of humanity, we should not be reflecting on this issue, as it has no use for the innate survival of humanity.

From a brief survey of the topic on Wikipedia. I was surprised that the lateralization of the brain is conjectured to not only encompass creativity and learning, but also the self and others. Very enlightening. Part of the criticism appears to be around the dating of an early literary work, the "Epic of Gigamesh". I wouldn't know either way and I can't judge on that alone. What seemed more justifiably concerning however, was that proliferation and cultural penetration of genetics was very unlikely to happen in just centuries, if I am not misunderstanding the implied timeline. Lactose tolerance/persistence started at about the same time, even earlier, and we are still observing significant amount of intolerant people unevenly distributed around the globe's continents. If this theory is suggesting a new genetic allele, it is either suggesting that it was dominant or that it was highly advantageous, or that not all of us have the ability developed in this regard? If idea was elaborated in terms of graduations, it would allow some people to develop lower IQ for this reason, but if we are talking about one spontaneous mutation, I would expect some non-negligible part of the population would still continue to be unaware of their intents and function like animal species. — simeonz

The point is that this hypothetical evolution did not occur over a span of centuries, but it was a process that lasted more than 6,000 years - let it be clear that, the "Bicamerality of the mind" discussed here, if taken as a fact, only ceased to exist as a norm in humanity less than 5,000 years ago, but quite possibly, it existed since the beginning of the species more than 200,000 years ago - and that "collapsed" together with the complex society that it slowly built - of which, its synthesis was the Bronze Age -.

Mutations and biological genetic changes can occur occasionally within millennia; together with the evolution that had occurred during the period, and the radically changing establishment by the new reality that humanity saw itself with the end of the bronze age, it is possible that such adaptation may have occurred.

Concerning Jaynes's focus on the Middle East and the European region, and the historical period he chose to talk about his theory, it is possible to find evidence of such a structuring of the mind not only in the same region before the period he studied - as I prove with my article - but also in other regions of the world.

The oldest inscriptions ever found in China - between 6,000 and 5,000 BC - are known as "Bone Oracles" - inscriptions made on human and other animal bones - which are, in their entirety, conceptions of their writers received by "divine sources" - another proof of the perception of ancient humanity that their own introspectiveness - the voice - was not of them but of the Gods -.

I believe that in resume, we could conclude from Jayne's work, the following:

"It is made obvious that, through the study of ancient humanity, they - the ancients and pre-historic humans - did not think the same way as we do."

We take as "normal" the way in which we structure our perception of reality based on our experiences.

Most likely, not even the Romans, who established a civilization as globalized, prosperous, diverse, and pluralistic as ours did not think like today's humans, and the same can be concluded from the future's humanity.

Does that give them some kind of substitute cognitive loop, without explicit self-referentiality, or was it incomparably limiting experience? Just to be clear about the distinguishing cognitive aspect - I surmise that we are talking about lack of acknowledged mental agency, not merely lack of auto-psychological skill. I assume that those people did probably understand involvement in situations, just not involvement in mental judgements, if I interpreted the conjecture correctly. — simeonz

Jaynes theorizes that the lack of self-awareness was not only a lack of meta-realization but also a biological disability of humans at the time - that's why he theorizes that they perceived the world in a quasi-schizophrenic state -. For him, humanity was unable to conceive introspective thoughts because of the structuring of the brains of the people of the era.

My perception agrees much more with the view that, humankind, at that time, only lacked the realization that they were capable of introspection thanks to the cultural, social, moral and technological limitations of the period in question. It's very probable that the biological composition and structuring of the brain remains the same, what differentiates us - unicameralists - from the bicameralist humanity is the way in which we began to structure "our interpretation of the structuring of reality".

P.S. Thanks. For the interesting and conscientiously presented work. — simeonz

Thank you for taking the time to read and conduct your inquiries from my article. -

Gus Lamarch

924I was read Bucke's, 'Cosmic Consciousness' fairly recently and I think that it is a fascinating area for discussion, but similarly I would not wish to derail the thread. The whole area of debate opened up by Gus's exploration of the ideas of Jaynes and associates ones, opens up fascinating possibilities for discussion, but I imagine that we need to be patient to wait and see what direction he wishes the thread to take. I certainly would not wish to mess it up. — Jack Cummins

Gus Lamarch

924I was read Bucke's, 'Cosmic Consciousness' fairly recently and I think that it is a fascinating area for discussion, but similarly I would not wish to derail the thread. The whole area of debate opened up by Gus's exploration of the ideas of Jaynes and associates ones, opens up fascinating possibilities for discussion, but I imagine that we need to be patient to wait and see what direction he wishes the thread to take. I certainly would not wish to mess it up. — Jack Cummins

The discussion exists so that it can take the course that it decides. It is not up to me to decide it. -

Jack Cummins

5.7k

Jack Cummins

5.7k

Okay, that's useful to know, because it is just that the whole area of thought arising from the ideas of Jaynes, leads onto so many other ones. The question of how consciousness developed in human culture gives so much scope for speculation. -

Jack Cummins

5.7k

Jack Cummins

5.7k

One aspect which I think is particularly interesting is your remark that about mental commands believed to be coming from gods or God. This has specific relevance for considering the whole spectrum of visionary experiences, which would probably include auditory aspects.

I am particularly interested in Jung's ideas about religious experience. One idea which he develops about modern human experiences is that in many ways aliens have replaced angels and, he sees people's experiences of such phenomena as having a basis in the psyche rather than in the objective world. However, while Jung speaks of alien encounters, there are many people who do claim to see spirit guides. Jung himself, spoke of his encounter with a guide which he referred to as Philemon.

Of course, many people who hear voices in our time do struggle with them and some act on the voices. Also, some people hear voices which are extremely unpleasant. If the bicameral mind thesis is correct, I wonder if the problematic nature of psychosis is because voices, and other hallucinatory experiences, occur out of context of a general bicameral way of being. -

Gus Lamarch

924Of course, many people who hear voices in our time do struggle with them and some act on the voices. Also, some people hear voices which are extremely unpleasant. If the bicameral mind thesis is correct, I wonder if the problematic nature of psychosis is because voices, and other hallucinatory experiences, occur out of context of a general bicameral way of being. — Jack Cummins

Gus Lamarch

924Of course, many people who hear voices in our time do struggle with them and some act on the voices. Also, some people hear voices which are extremely unpleasant. If the bicameral mind thesis is correct, I wonder if the problematic nature of psychosis is because voices, and other hallucinatory experiences, occur out of context of a general bicameral way of being. — Jack Cummins

I find interesting your comment on the problematization caused by the misunderstanding of potentially "bicameral" minds.

It is a fact that such a perception of the world, if true, if witnessed by an exclusive individual who sees himself established in a species already pre-established in the unicameral structuring of consciousness, would be completely frowned upon and even expunged from such a society, through legitimate justifications in the differentiation of the perception of the world, and consequently, of its conclusions about reality.

Jaynes in his book does not disregard the possibility that individual cases are experienced by "consciously modern" humans to occur. He even cites the example of a "modern" case of the bicameral mind, and its consequences:

"An exclusive and recent case of the construction of a bicameral mind can be found in Joan d'Arc. She had an isolated childhood, almost in a complete destruction of the social relationship pre-established in the first years of life. It had been seen by her contemporaries that Joan had a different experience of reality, be it for her moments of "contact with God" and for her physiognomy and distant expression, almost unconscious of herself. That the only answer found by society was that of the total extermination of such a vision in opposition to the common "reality" is not incomprehensible as we ourselves put them into asylums in a petty way of empathic falsehood." -

Gus Lamarch

924I think it is certainly true that different eras give rise to completely different forms of consciousness. — Wayfarer

Gus Lamarch

924I think it is certainly true that different eras give rise to completely different forms of consciousness. — Wayfarer

Indeed. -

Jack Cummins

5.7k

Jack Cummins

5.7k

I had a strange coincidence today. I was in a newsagents, looking at magazines and, I found a magazine with an article which discusses Julian Jaynes' ideas on the bicameral mind. The article is in 'New Statesman' (26 March- 15 April 2021).It is called, 'The voice in your head', by Sophie McBain. It discusses a psychiatrist, Maurius Romme, who took a particular interest in the work of Jaynes. He had used it as a basis for aiding people who hear voices. Romme was interested in the work of Charles Fernyhough, who focused on the way in which thoughts are processed as inner speech and the role of trauma, which can lead to dissociation of consciousness.

Romme worked with a particular woman, Patsy Hage, a voice hearer, who contributed to Romme's writing. The writer of the article summarises how Patsy Hage,

'found it remarkable how similar the gods were to the voices she heard. They dispensed threats and orders, they bullied and mocked, they provided comfort and advice. The gods were always obeyed, just as she and other voice-hearers often obeyed their voices, finding it hard to know where the voices ended and their true selves began. "We voice-hearers are probably living in the wrong era," she concluded.

Apart from the article, I think another area relevant to your discussion is the way in which hallucinogenics can trigger voices. When I experimented on cannabis biscuits and Lsd at a warehouse rave, I experience voices. I was worrying about all the work I had to do on the course I was doing and I began hearing voices, telling me, ' Its a very life' repeatedly and, also, when I kept hearing voices saying, 'He's eaten skunk cake'. I was not sure if the voices were probably in my head or external, because

boundaries seemed unclear. Perhaps, hallucinogenics trigger a throwback to a bicameral mental state. -

unenlightened

10kEstimates of the current prevalence of hearing voices vary from less than 1% to over 80%.Of course, many people who are hear voices in our time do struggle with them and some act on the voices. Also, some people hear voices which are extremely unpleasant. If the bicameral mind thesis is correct, I wonder if the problematic nature of psychosis is because voices, and other hallucinatory experiences, occur out of context of a general bicameral way of being. — Jack Cummins

unenlightened

10kEstimates of the current prevalence of hearing voices vary from less than 1% to over 80%.Of course, many people who are hear voices in our time do struggle with them and some act on the voices. Also, some people hear voices which are extremely unpleasant. If the bicameral mind thesis is correct, I wonder if the problematic nature of psychosis is because voices, and other hallucinatory experiences, occur out of context of a general bicameral way of being. — Jack Cummins

Hearing voices is a matter of identification. I hear this voice in my head as I type, and identify with it - I call it "my voice". If one does not identify with it, but still has an identification with something, the body, perhaps, then the narrative voice is 'other'. A change of identification can seem world shattering, an end to identification can seem like death; but it is a very small tweak to one's point of view. -

bongo fury

1.8k

bongo fury

1.8k

:100:

And when I read your post I "imagine your voice", or so shiver my brain as to invite that modern rationalisation. Any rationalising is potentially disturbing. I can easily "hear" a chorus of competing drafts (more or less deranged) of each new sub-vocal thought. The more vivid the more deprived of sleep, I have to say. -

Jack Cummins

5.7k

Jack Cummins

5.7k

I do agree that the matter of hearing voices is about identification, although from discussion which I have had with people who hear them regularly, they are variable. Some voices seem to be perceived inside the head and others outside, and they can vary in intensity. Also, how people perceive the voices is an important distinction. I am more familiar with people believing that their voices are a form of psychic attack rather than being from God, but it does depend on underlying beliefs.

It does seem that the literal experience of voices as auditory hallucinations is related to brain chemistry, neurotransmitters, because antipsychotic medication seems to change it dramatically. What is also interesting is that medication also seems to alter the perception and interpretation of voices. I have come across people who still hear voices when they 'feel well' but see the voices as being 'unreal.'

Of course, we all have inner dialogue and while most people don't see describe them as voices, thoughts can be of an intrusive nature. They probably also reflect different aspects of the self

One idea which I think is relevant here is the concept of the daimon, which I believe goes back to Plato. This is related to the true, or higher self, and it could be that this daimon was experienced as an external voice in the consciousness of human beings in ancient cultures. -

unenlightened

10kIn case anyone wants some basic information about visions and voices as currently experienced or needs a friendly chat _

unenlightened

10kIn case anyone wants some basic information about visions and voices as currently experienced or needs a friendly chat _

https://www.hearing-voices.org/voices-visions/

Welcome to The Philosophy Forum!

Get involved in philosophical discussions about knowledge, truth, language, consciousness, science, politics, religion, logic and mathematics, art, history, and lots more. No ads, no clutter, and very little agreement — just fascinating conversations.

Categories

- Guest category

- Phil. Writing Challenge - June 2025

- The Lounge

- General Philosophy

- Metaphysics & Epistemology

- Philosophy of Mind

- Ethics

- Political Philosophy

- Philosophy of Art

- Logic & Philosophy of Mathematics

- Philosophy of Religion

- Philosophy of Science

- Philosophy of Language

- Interesting Stuff

- Politics and Current Affairs

- Humanities and Social Sciences

- Science and Technology

- Non-English Discussion

- German Discussion

- Spanish Discussion

- Learning Centre

- Resources

- Books and Papers

- Reading groups

- Questions

- Guest Speakers

- David Pearce

- Massimo Pigliucci

- Debates

- Debate Proposals

- Debate Discussion

- Feedback

- Article submissions

- About TPF

- Help

More Discussions

- Other sites we like

- Social media

- Terms of Service

- Sign In

- Created with PlushForums

- © 2026 The Philosophy Forum