-

Wayfarer

26.1kBut inasmuch as God is supposed to be a supernatural thing, I think it can't help but fail in that undertaking, because supernatural things by their very nature have no effect on the world that we experience (if they did, they would be natural), so we cannot tell anything about whether or not they are real, and so can only appeal to faith for claims about them. — Pfhorrest

Wayfarer

26.1kBut inasmuch as God is supposed to be a supernatural thing, I think it can't help but fail in that undertaking, because supernatural things by their very nature have no effect on the world that we experience (if they did, they would be natural), so we cannot tell anything about whether or not they are real, and so can only appeal to faith for claims about them. — Pfhorrest

That says much about your presuppositions. I did peruse your very well-written and presented website with some of the essays about this same question, but I think the distinction you're making is quite artificial. After all, what is supernatural and what is not, are usually defined almost solely in terms of previous religious doctrines - which, as I said, is a matter of cultural dynamics as much as anything else. Many of the things the modern world takes for granted might seem supernatural to earlier ages (although that's a problematical claim also.) 'Supernatural' and 'metaphysical' are Latin and Greek synonyms, so in effect, to confine the scope of philosophy to natural philosophy, is to confine the scope of reason to what can be known by the natural senses and mathematical inferences therefrom (which is after all the implication of empiricism.)

But, transcendental arguments, often invoked by Kant, show that reason itselfdoes not have a natural explanation. You might say, well reason is an adaptation, it can be explained in evolutionary terms. But then you are advocating evolutionary naturalism, which I argue is not a philosophy at all - it's a biological theory, and the only ends it can conceive of, are those of procreation and survival. 2 This is why many moderns are in effect nihilist, even if they don't know what that word means, and have never thought about philosophy or meaning or anything of the kind. Because they view life as the consequence of chance, and mankind as a kind of fluke of nature, then there's no real prospect of a philosophical relationship with the Universe. Sure, they're related in the way that evolution says everything is related, namely, as creatures, but humans are more than creatures, and the burden of the self-awareness that comes with that, if it not given some kind of larger goal, often results in an acute sense of meaninglessness. So that is why the well-known 'argument from reason' purports to indicate a goal beyond the merely sensory domain.

Every progress in evolution is dearly paid for; miscarried attempts, merciless struggle everywhere. The more detailed our knowledge of nature becomes, the more we see, together with the element of generosity and progression which radiates from being, the law of degradation, the powers of destruction and death, the implacable voracity which are also inherent in the world of matter. And when it comes to man, surrounded and invaded as he is by a host of warping forces, psychology and anthropology are but an account of the fact that, while being essentially superior to all of them, he is the most unfortunate of animals. So it is that when its vision of the world is enlightened by science, the intellect which religious faith perfects realises still better that nature, however good in its own order, does not suffice, and that if the deepest hopes of mankind are not destined to turn to mockery, it is because a God-given energy better than nature is at work in us. — Jacques Maritain

The Subjects of Reality

What is the nature of the mind, inasmuch as that means the capacity for believing and making such judgements about what to believe? — Pfhorrest

Here I have a principle which is rarely appreciated or even understood. It is based on an profound passage in the Brihadaranyaka Upaniṣad. It has been paraphrased and commented on by a contemporary scholastic swami, as follows. This is a passage comprising a dialogue between a questioner and a Vedantic sage, Yājñavalkya, regarding the nature of ātman, the Upaniṣadic 'self of all':

[The questioner asks] "You have only told me, this is your inner Self in the same way as people would say, 'this is a cow, this is a horse', etc. That is not a real definition. Merely saying, 'this is that' is not a definition. I want an actual description of what this internal Self is. Please give that description and do not simply say, 'this is that'.

Yājñavalkya replies: "You tell me that I have to point out the Self as if it is a cow or a horse. Not possible! It is not an object like a horse or a cow. I cannot say, 'here is the ātman; here is the Self'. It is not possible because you cannot see the seer of seeing. The seer can see that which is other than the Seer, or the act of seeing. An object outside the seer can be beheld by the seer. How can the seer see himself? How is it possible? You cannot hear the hearer of hearing. You cannot understand the Understander of understanding. That is the ātman."

Source

There is a paper by the French philosopher of science, Michel Bitbol, It is never known but is the knower: consciousness and the blind spot of science which elaborates this point from a contemporary perspective.

So the crucial point about this is that we have to learn to see beyond the process of 'objectification'. Objectification is seeking understanding solely in terms of what is objectively knowable, quantifiable, measurable. The evolutionary account of mankind is, generally, objectively true; but humans are not only objects, they are subjects of experience, and subjecting philosophy to the procrustean bed of scientific naturalism conceals that about them which is completely inexplicable in naturalistic terms (also the source of the 'hard problem of consciousness' which, of course, evolutionary naturalists must deny exists.)

Of course objectivism has many strengths in the objective domain as 'methodological naturalism'. When it becomes metaphysical naturalism then it exceeds its warrant and becomes a form of dogmatic belief, strangely mirroring the dogmatic belief-system which it descended from.

---------

2. The subject of an excellent essay by contemporary philosopher Thomas Nagel, Evolutionary Naturalism and the Fear of Religion (pdf). -

180 Proof

16.4kDo X and people will like you and help you. Do Y and people will dislike you and hinder you. We want to be liked and helped. Our dependence is extreme, and therefore hard for us to confess. — Eee

180 Proof

16.4kDo X and people will like you and help you. Do Y and people will dislike you and hinder you. We want to be liked and helped. Our dependence is extreme, and therefore hard for us to confess. — Eee

Sounds rather ... transactional. Manipulative. A narcissistic "dependency". At best, instrumental; not ethical in the least. Motivated "to be liked and helped" and "not disliked and hindered" rather than motivated to help and not to do harm. You "confess" a parody, Eee, or to arrested development - I can't tell which. So tell me what I'm missing. :confused: -

Eee

159

Eee

159

Ha. Well, it does look cynical as I reread it. Or cold. But try to see it from a alien point of view, without taking sides. And without dragging in more subjective words. What does a tribe punish or reward? Even an alien without human feelings could find patterns in that. For this you get a medal and a parade. For that you get a noose.

Obviously I could have given a more flowery version. As I said in another thread, the mature person embraces good laws as the highest expression of their freedom. -

Possibility

2.8kI'm not sure I understand you, and that makes me wonder if perhaps you misunderstood me. I was trying to say that wisdom is basically being able to evaluate both descriptive and prescriptive claims: where descriptive claims are those about what is or isn't, what's true or false, what's real or unreal; and prescriptive claims are those about what ought or oughtn't be, what's good or bad, what's moral or immoral. It sounds like you're saying that figuring out what's false, bad, unreal, or immoral is just as important as figuring out what's true, good, real, and moral; and I meant that to be implied by what I said before. Wisdom is the ability to discern one from the other (in both dimensions), or at least to place ideas somewhere in relation to each other on each of those scales. For the purposes (as will be elaborated later) of telling both where we are and where to go, figuratively speaking, and thus how to get there from here. — Pfhorrest

Possibility

2.8kI'm not sure I understand you, and that makes me wonder if perhaps you misunderstood me. I was trying to say that wisdom is basically being able to evaluate both descriptive and prescriptive claims: where descriptive claims are those about what is or isn't, what's true or false, what's real or unreal; and prescriptive claims are those about what ought or oughtn't be, what's good or bad, what's moral or immoral. It sounds like you're saying that figuring out what's false, bad, unreal, or immoral is just as important as figuring out what's true, good, real, and moral; and I meant that to be implied by what I said before. Wisdom is the ability to discern one from the other (in both dimensions), or at least to place ideas somewhere in relation to each other on each of those scales. For the purposes (as will be elaborated later) of telling both where we are and where to go, figuratively speaking, and thus how to get there from here. — Pfhorrest

I don’t think I’ve misunderstood you - I’m talking about how we then relate to what is false or immoral or what we claim ‘oughtn’t be’. Wisdom is more than just evaluating claims - it includes determining and initiating action in relation to those claims. I think that wisdom breaks down, for instance, when we isolate, exclude or attack what is but oughtn’t be. -

Eee

159

Eee

159

Hey, 180. It was in the same post that I amplified that thought. The cynical intro (perhaps an unconscious rhetorical device to rope in the grumps and haters) is followed by a little birdsong about the better angels of our nature.

It does seem to me that most prescriptive claims manifest the best part of our nature. Good laws and traditions aren't bondage but rather the highest expression of our freedom even (another stolen though[t].)....[W]ith time it became clear [to me] that many prohibitions are simply successful self-sculpture. We live above such things. Humans take profound pleasure in denying themselves things, and this is great. — Eee

We deny ourselves lying and stealing as beneath us, for example. Or we scoff a gas-guzzling SUVs or fast food or sloppy thinking, and so on. We enjoy carving away what is vulgar, too easy. I do think narcissism is involved, even profoundly involved, but I suggest that this narcissism is a group narcissism even when the group is potential rather than actual. -

Eee

159Bonus question: What do aesthetic claims, about beauty and comedy and tragedy and such, mean, and how do they relate to prescriptive claims about morality?

Eee

159Bonus question: What do aesthetic claims, about beauty and comedy and tragedy and such, mean, and how do they relate to prescriptive claims about morality?

The Objects of Morality

What are the criteria by which to judge prescriptive claims, or what makes something moral? — Pfhorrest

Roughly I think we try to make harmony out of cacophony of drives. While philosophers emit neat little systems of abstract nouns, artists give us flesh-out protagonists, showing rather than telling. Not always but quite often the virtuous protagonist is also physically beautiful. And even our poets (musicians these days) are as visual as they are sonic. We get the total package, an absolute art of virtuous flesh. Musicians offer us visceral attitudes that we can make our own. Not only the words, but also the clothes, the moves,... I'm a bit old to take video-musicians as my exemplars, but I think that many, many people get their philosophy viscerally-lyrically like this. Arguably the primary product is an entire personality. While the less bold imitate as well as they can, the bolder create their own fusions, which occasionally become famous/dominant and keep the game going. -

Brett

3k

Brett

3k

The Importance of Justice

Why does is matter what is moral or not, good or bad, in the first place? — Pfhorrest

I think you have to decide whether we are in a good place or not. If we’re in a good place it’s because of how we acted morally. Those morals formed societies that allowed us to evolve and develop, they’re behind what we regard as civilisation. Justice itself demonstrates the continued belief in those morals by acting on them.

That these morals are universal is proved by the commonality of successful societies. -

180 Proof

16.4k4.0

180 Proof

16.4k4.0

Bonus question:

What is the meaning of life? — Pfhorrest

4.1 If there was ever a pseudo-question (see 1.311) it's this one: "What is the ...

4.11

• ... 'meaning' of life" to whom?

• ... 'meaning' of life" for what?

• ... ???

4.12 Substitutes for 'meaning': purpose, goal, function, direction, destination, value ...

4.2 To make this less 'pseudo', I drop 'meaning' and insert purpose reformulating the question this way:

4.21 Q -

What is the purpose - primary task - of life?

4.211 A(philo) -

In the grandest sense, the struggle against stupidity (i.e. FOOLERY, or 'denial of contingency' (e.g. Rosset's "doubling", Becker's "symbolic self", Zapffe/Camus' "absurd", Spinoza's "bondage"), THAT MALADAPTIVELY SELF HARMS AND/OR HARMS OTHERS) - an infinite, yet reflective, task which I propose uniquely belongs to philosophy (see 1.1, 1.12, 2.62, 2.9, 3.8).

"Mit der Dummheit kämpfen Götter selbst vergebens."

~ F. S.

4.212 A(nonphilo) -

In a more technoscientific ( :wink: ) sense, in so far as inanimate matter (far-from-equilibrium entropy) has afforded animate matter (life) to emerge:

• life affords intelligence (i.e. optimization of adaptive error-correcting problem-solving) ...

• intelligence affords immortality ...

• immortality affords ephemeralization (i.e. yocto-compression of technoscience + matter & energy consumption: in effect, "doing more and more with less and less" ... until everything can be done with nothing)

:death: :flower:

4.3 Meaning presupposes context. Life is the context of the living. Context itself has no (wider) context; it is meaningless.

4.31 Life goes on without meaning. Yet the living demand - imagine - otherwise. Origin of art? music? dance? lovemaking (as opposed to merely fucking)? ... religion?

4.32 Each living thing means everything to herself as evidenced by her involuntary drive to survive and thrive. Eusociality emerges from shared recognition that each living member of a group means everything to herself. Thus, they are meaningful to one another through mutual recognition. Reinforced by natality and kinship bonds.

4.33 "The meaning of life" becomes manifest in common, as a commons, or soil of community-roots, cultivated and thereby reproduced through culture (i.e. forms of life --> language-games).

“Blues music is an aesthetic device of confrontation and improvisation, an existential device or vehicle for coping with the ever-changing fortunes of human existence, in a word, entropy, the tendency of everything to become formless. Which is also to say that such music is a device for confronting and acknowledging the harsh fact that the human situation . . . is always awesome and all too often awful . . . But on the other hand, there is the frame of acceptance of the obvious fact that life is always a struggle against destructive forces." ~Albert Murray

4.4 "What's my philosophy?" Don't be a fool (or an asshole) - minimize frustrations by reflectively aligning expectations with the real - is the whole of philosophy; the rest, like the Rabbi says, is commentary. (See 2.52)

Thus Spoke 180 Proof.

:fire: -

AnarchoRedneck

7I haven't the slightest clue.

AnarchoRedneck

7I haven't the slightest clue.

I never went to college, and I'm only beginning to understand just how little I know about anything.

But I think I'm somewhere trying to examine the differences between enlightenment and romantic thought that converged together to build fascistic philosophy so that I could maybe through some different experiences render it hypocritical and self-defeating.

...and I realized once again how little I understand about anything. -

Pfhorrest

4.6kI don’t think I’ve misunderstood you - I’m talking about how we then relate to what is false or immoral or what we claim ‘oughtn’t be’. Wisdom is more than just evaluating claims - it includes determining and initiating action in relation to those claims. I think that wisdom breaks down, for instance, when we isolate, exclude or attack what is but oughtn’t be. — Possibility

Pfhorrest

4.6kI don’t think I’ve misunderstood you - I’m talking about how we then relate to what is false or immoral or what we claim ‘oughtn’t be’. Wisdom is more than just evaluating claims - it includes determining and initiating action in relation to those claims. I think that wisdom breaks down, for instance, when we isolate, exclude or attack what is but oughtn’t be. — Possibility

I don't think we disagree in the end. As I frame it, all action is driven by a combination of what we think is and what we think ought to be, so the practical upshot of evaluating both of those kinds of claims is always in driving our actions. And it is precisely those differences in evaluation between the two scales, what is but oughtn't be, or ought to be but isn't, that are the primary drivers of such action, as we act always to eliminate that difference, and make what (we think) is into what (we think) ought to be.

4.4 "What's my philosophy?" Don't be a fool (or an asshole) is the whole of philosophy; the rest, like the Rabbi says, is commentary. — 180 Proof

That's a great summary. (And I enjoy that, being point 4.4, it is the fourest point in your response. I like fourest things, it's in my name; I was even born at 4:44 PM).

I've been so busy I've been falling behind on answering my own questions one per other response, so I'll do a couple more now:

The Institutes of Philosophy

Who is to do philosophy and how should they relate to each other and others, socially speaking? — Pfhorrest

The question is largely whether philosophy is a personal activity, or an institutional one. Given that I have just opined that the faculty needed to conduct philosophy is literally personhood itself, it should come as no surprise that I think that philosophy is for each and every person to do, to the best of their ability to do so. Nevertheless, institutions are made of people, and I do value the cooperation and collaboration that has arisen within philosophy in the contemporary era, so I don't mean at all to besmirch professional philosophy and the specialization that has come with it. I merely don't think that the specialized, professional philosophers warrant a monopoly on the discipline. It is good that there be people whose job it is to know philosophy better than laypeople, and that some of those people specialize even more deeply in particular subfields of philosophy. But it is important that laypeople continue to philosophize as well, and that the discourse of philosophy as a whole be continuous between those laypeople and the professionals, without a sharp divide into mutually exclusive castes of professional philosophers and non-philosophers. And it is also important that some philosophers keep abreast of the progress in all of those specialties and continue to integrate their findings together into more generalized philosophical systems.

(I feel like I weirdly straddle all those divides, having some degree of professional education in the field but not nearly deep enough to teach it professionally, and working on a generalized philosophical system that draws from the more contemporary findings of all those specialties).

The Importance of Philosophy

Why do philosophy in the first place, what does it matter? — Pfhorrest

On the one hand, doing philosophy is literally practice at being a person, exercising the very faculty that differentiates persons from non-persons. Doing philosophy literally helps develop you into a better person, increasing your self-awareness and self-control, improving your mind and your will, and helping you to find meaning in the world, both in the sense of descriptive understanding, and in the sense of prescriptive purpose.

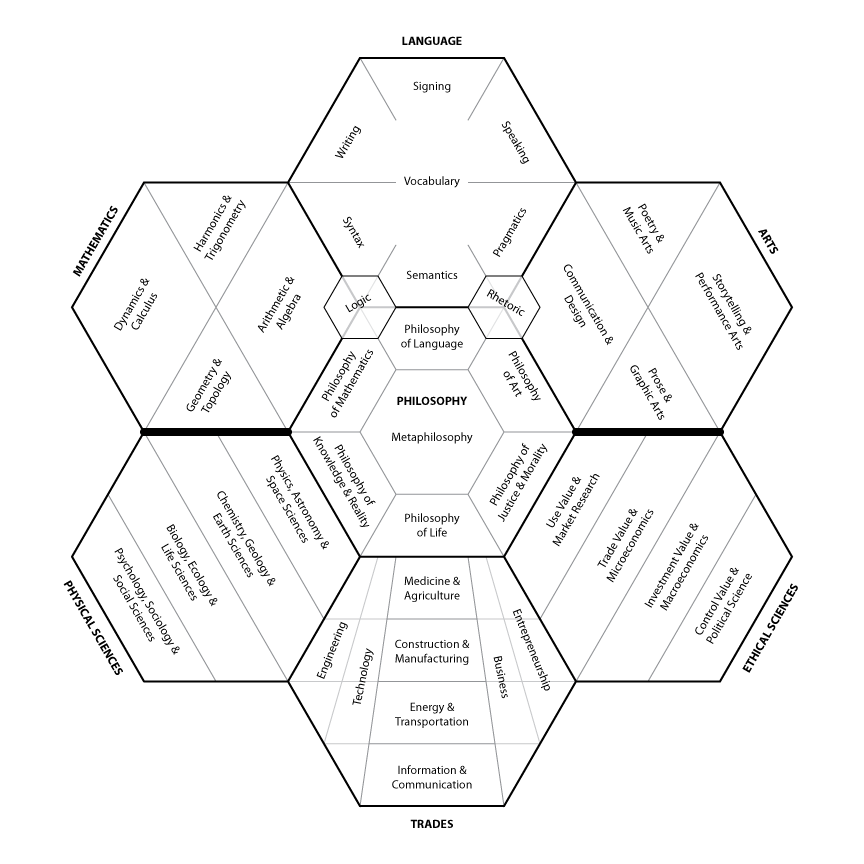

But also, as I already elaborated upthread, I think philosophy is sort of the lynch pin of all human endeavors. All the many trades involve using some tool to do some job. Technology administers those tools, business administers those jobs; engineers make new tools, entrepreneurs make new jobs; the physical sciences find more "natural tools" for the engineers to work with, and the ethical sciences I propose would find more "natural jobs" (i.e. needs that people have) for the entrepreneurs to work toward. Both those physical and ethical sciences depend on philosophy for the tools they need to do their jobs. Philosophy in turn relies on the tools of language, mathematics, and the arts to do its job, and then reflexively also examines those topics, as well as itself.

I drew a picture:

-

Eee

159Cynical I get. My only point is that you didn't answer the question. 'Ethics' is an urgent need because we are so species-defective. — 180 Proof

Eee

159Cynical I get. My only point is that you didn't answer the question. 'Ethics' is an urgent need because we are so species-defective. — 180 Proof

I think I'm slow to offer a particular ethics because it would feel like merely spouting preferences. I think that knowledge might even come, to some degree, at the cost of righteousness. If I cling to an identification with the good, that may force me block out an understanding of 'evil.' This connects to one image (among others) of the philosopher as a kind of alien. -

Eee

159Wittgenstein showed that philosophy, yes in it's entirety, consists in language on being on holiday. And that's it really. It supposedly ends in quietism. — Wallows

Eee

159Wittgenstein showed that philosophy, yes in it's entirety, consists in language on being on holiday. And that's it really. It supposedly ends in quietism. — Wallows

It seems to me that only a certain kind of philosophy is subject to that accusation. Philosophy often seems to operate at the strategic level of human affairs. People wrestle with where we should be going, what kinds of arguments or people should be trusted, etc. It wrestles with whether 'I' should volunteer for the next war or have children or stop reading philosophy and learn to code. How is this more 'on holiday' than asking a bus-driver to pull over or telling a kid not too talk with her mouth full?

Strangely enough it's the philosophy just adjacent to Wittgenstein's (language-obsessed stuff) that seems most subject to the accusation. I love Wittgenstein, but still... -

Pfhorrest

4.6kThe Meaning of Reality

Pfhorrest

4.6kThe Meaning of Reality

What do descriptive claims, that attempt to say what is real, even mean? — Pfhorrest

I hold to roughly the verificationist theory of meaning, but limited in domain to only descriptive propositions, those trying to say what is real. That is to say the such claims communicate an idea, a mental image (in more senses than just vision) of the world being some way, and an attitude toward that idea such that the idea is meant to fit the world: you should expect to find the world that way, and if you don’t, the idea is wrong, not the world. -

Possibility

2.8kThe Meaning of Philosophy

Possibility

2.8kThe Meaning of Philosophy

What defines philosophy and demarcates it from other fields? — Pfhorrest

Philosophy is the seeking of wisdom - not simply knowledge, or even an understanding of the world. As such it permeates every field. To demarcate the seeking of wisdom from any field of endeavour is to claim that there is no wisdom to be found in that field. I think you showed this with your diagram.

Knowledge is an awareness of information; Understanding is the connection we make with the information we have about the world; and Wisdom is how we collaborate with that information. Wisdom ties in with knowledge and understanding in such a way that all three are inseparable. You can’t really understand something, even if you think you know as much as you can about it, until you can apply that knowledge in how you interact with the world. In the same way wisdom isn’t really wisdom if we ignore information or cannot (or will not) strive to understand all the information available to us.

Philosophy values all information, regardless of its current usefulness, and seeks to make effective use of all that we know and understand about the world - paying particular attention to what we don’t yet know, what we know but fail to understand, and what we know and understand but fail to integrate or apply to our interactions with the world. -

Possibility

2.8kThe Objects of Philosophy

Possibility

2.8kThe Objects of Philosophy

What is philosophy aiming for, by what criteria would we judge success or at least progress in philosophical endeavors? — Pfhorrest

Philosophy aims to structure and restructure our conceptual models of the world, to make the most effective use of all the information we have. Progress in philosophical endeavour, then, is achieved when we can account for anomalous data or experiences, when we can include and collaborate with alternative viewpoints, and when we can revive and integrate suppressed or forgotten knowledge into how we interact with the world.

Successful philosophical endeavour aims to integrate useful information from disparate sources for application to living well - ie. interacting with the world with less prediction error.

The Method of Philosophy

How is philosophy to be done? — Pfhorrest

All information is potentially useful, so the first step would be to reserve judgement on information in an objective sense.

We are, however, each progressively limited in our capacity to be aware, connect and collaborate with information by the five dimensions of our existence, and so we cannot always make use of information ourselves. We are equipped, all the same, with the means to share that information with those for whom it may prove much more useful.

Philosophy may sometimes involve, therefore, extracting incomplete information as raw experience from what has been integrated and reduced to suit these individual or cultural limitations any number of times. This may involve grafting the information onto our own experiences or other experiential accounts, or borrowing structural patterns as a guide to completing the experiential information. This type of speculative philosophy is fraught with error, but relying only on reducible information encourages us to be dismissive of the additional aspects available in information from subjective experience. Keeping track of where and how we depend on assumptions, concepts and modelling can be more important than avoiding them altogether. -

creativesoul

12.2kAll attribution of meaning consists of correlations drawn between different things. I would not pursue a question about the meaning of descriptive statements.

— creativesoul

I don't understand what you're trying to say. — Pfhorrest

Did you understand the first claim? -

Possibility

2.8kThe Subjects of Philosophy

Possibility

2.8kThe Subjects of Philosophy

What are the faculties that enable someone to do philosophy, to be a philosopher? — Pfhorrest

Short version, I think self reflection and self evaluation are the key faculties for doing philosophy. The capacity to be aware of our conceptual systems, and be critical of the specific way that we interact with the world in relation to how the universe interacts with each other in its diversity, provides the potential for us to strive towards more accurate conceptual systems that minimise prediction error while maximising interaction.

I think an effective philosopher has a handle on critical and creative thinking, and employs an inclusive approach to knowledge. Courage, respect and curiosity also enable one to do philosophy without limitations.

The Institutes of Philosophy

Who is to do philosophy and how should they relate to each other and others, socially speaking? — Pfhorrest

A closed mind cannot do philosophy. If you take the trouble to avoid making mistakes, then perhaps philosophy isn’t for you. History shows that philosophers can’t really avoid being mistaken about something. The best we can hope for is the rare gem of conceptual structure that leads us to new ways of thinking.

The mind isn’t structured temporally or spatially, but according to value. Reality, however, is ultimately structured according to meaning. So when we relate to each other, socially speaking, it should be with a focus on a shared value regardless of distance, space or time. But when we relate to what others experience, particularly the form in which they present it to us, it should be with a focus on reaching a shared sense of meaning regardless of value.

The Importance of Philosophy

Why do philosophy in the first place, what does it matter? — Pfhorrest

When we interact with the world, we encounter new information. We either use that information in subsequent interactions with the world, or we don’t. If we do, then the way that we use it, our philosophy, matters. But it is also the information that we don’t use, and why - the value and significance we attribute to information - that structures this philosophy.

Evolutionary theory says that the most important thing we pass on to our descendants is our genetic information, but I disagree with this. The way I see it, the most important thing we pass on is the capacity to make effective use of new information. Without it, we’re not really living, are we? -

Pfhorrest

4.6kI think the distinction you're making is quite artificial. After all, what is supernatural and what is not, are usually defined almost solely in terms of previous religious doctrines — Wayfarer

Pfhorrest

4.6kI think the distinction you're making is quite artificial. After all, what is supernatural and what is not, are usually defined almost solely in terms of previous religious doctrines — Wayfarer

You'll note that in that essay (thank you for the praise BTW) I explicitly clarify what I mean by supernatural, and say that I'm not saying that any of the particular things that are called supernatural definitely don't exist -- just that if they exist, in any way that we can notice that their existence, then they are natural things. If some ghost hunters manage to actually capture incontrovertible evidence for ghosts, for example, I'm not going to say "that's supernatural so it doesn't count", I'm going to look forward to the amazing scientific discoveries that are sure to follow from this newly-confirmed unexplained phenomenon.

So if by "God" someone means something that has a noticeable effect on the universe, such that we could tell by looking at the universe whether or not such a being existed, then that's a natural phenomenon they're positing, and they're welcome to do science to it without any philosophical complaint from me -- but also vulnerable to science being done about it, perhaps to conclusions they don't like. Many people in modern ages therefore place their notion of God as something entirely beyond that kind of experiential import, which then puts it into the category of supernatural as I mean it, about which we can only believe one way or another on faith. (Look at all the agnostics and theists on this very forum who insist that atheism also be taken on faith, because God as they mean it is beyond the proof or disproof.)

reason itself does not have a natural explanation — Wayfarer

I'm not sure what you mean here. What exactly about reason is in need of an explanation? "How did humans come to be able to use reason?"? That is, as you say, not a philosophical question, but a biological one, and evolutionary explanations work just fine there. I suspect you mean something deeper and more philosophical than that though, or at least you want to mean that, but I'm not clear what it is exactly.

Thank you for your responses!

You'll have to tell me if I understand you right. That sounds to me like you're saying all meaning is of the type meant by expressions like "clouds mean rain" and "smoke means fire": one thing signifies another thing, because of the correlation between those things. Is that what you mean by that claim? If so, what do you take statements that purport to describe reality to signify, or correlate with -- what do they mean? Or if you somehow object to asking that question, can you explain why?All attribution of meaning consists of correlations drawn between different things. I would not pursue a question about the meaning of descriptive statements.

— creativesoul

I don't understand what you're trying to say. — Pfhorrest

Did you understand the first claim? — creativesoul

Oh boy, this is a fun one.Bonus question:

What do mathematical claims, about numbers and geometric shapes and such, mean, and how do they relate to descriptive claims about reality? — Pfhorrest

Mathematical claims are ultimately claims about the logical implications of definitions — you state some axioms that define what rules the imaginary objects under discussion are defined to obey, and then explore in more details the logical implications of objects that have to obey those rules. In one sense this is completely detached from any claims about reality -- at least, about concrete reality, the world that we can experience. But as I will elaborate in my answer to the next question, the actual existent objects of that concrete reality aren't the sorts of things that we ordinarily think of as "real", things like rocks and trees and such. Rather, those are themselves abstractions aware from the more fundamentally, concretely real things, projected behind the concrete reality we have direct contact with as an explanation of that. More and more abstract, and recognizably mathematical, objects are projected behind those things, the objects of our theories of physics. All of those things are "real" in an instrumental sense, lying in the intersection of abstract and concrete things: they are abstract objects that are instrumental in explaining concrete reality, and so concretely real to that extent.

But behind all of those, we aim to construct a single mathematical object that is a 1:1 map of concrete reality, a theory of everything. Whatever mathematical object that will turn out to be just is concrete reality: "concrete" is indexical, it signifies only the mathematical structure of which we are also a part. Other mathematical objects are just like it, ontologically, except that we aren't a part of them; they are purely abstract, with no connection to the object of which we are a part. This is unlike Platonism in that it doesn't posit that there is the world we're familiar with and then separately some kind of Heaven full of Forms. In terms comparable to that, I'd say that there are only Forms, no Heaven in which they exist, and one of those Forms just is the concrete universe we're familiar with (which, like most mathematical objects, is constructed out of lots and lots of copies of simpler objects, which is why we see other "Forms" expressed within our concrete world). -

Possibility

2.8kThe Meaning of Reality

Possibility

2.8kThe Meaning of Reality

What do descriptive claims, that attempt to say what is real, even mean? — Pfhorrest

When we attempt to describe what is real, we draw from our conceptual system: from what we assume exists, and from what we predict will occur. These conceptual systems have been developed from information gained through past interactions with the world, and evaluated whenever we encounter prediction error: when what assume or predict doesn’t match with the information coming in. This occurs more often as children, as our conceptual systems develop, and it’s expected that we encounter less new information or prediction error as adults - that the mark of a fully-formed adult is to know what is real. But the mark of a philosopher is to recognise that our conceptual systems are in a continual state of flux.

The Objects of Reality

What are the criteria by which to judge descriptive claims, or what is it that makes something real? — Pfhorrest

Reality has a number of aspects that correspond initially to the dimensions with which we are familiar: one dimensional reality consists of a linear relationship between two points, two dimensional reality determines shape, and three dimensional reality determines a spatial aspect. The fourth dimension of reality determines a temporal aspect, and it is at this point that the way we talk about reality must take into account the role of the observer. As much as we can map and measure these first three dimensions objectively, we are far less certain of our own temporal positioning in the world.

To map two dimensions, the information must be obtained in relation to a three dimensional viewpoint - ie. from above. To map three dimensional reality, therefore, the viewpoint must be four-dimensional: measured in relation to a temporal aspect. We often forget that this external viewpoint even exists, pointing to an aspect of reality that is necessary to confirm what is real.

Here’s where it gets interesting. We know that the universe exists as a four-dimensional reality at minimum - and that we are four dimensional - because we can confirm a three dimensional aspect to reality. But in order to know anything about this four dimensional aspect, the information must be obtained in relation to a five-dimensional viewpoint: from a position beyond time.

It has been our naive attempts to blindly navigate this five dimensional aspect of reality that has enabled us to develop any understanding at all about time outside of our direct experience. What began as a recognition of elements of reality that transcend and connect our experiences to those of our ancestors and descendants, soon developed into concepts such as family, people, gods, eternity, infinity, space, energy, gravity, etc - enabling us to relate to and understand this reality that we know exists beyond our bodily or temporal experience.

The Methods of Knowledge

How are we to apply those criteria and decide on what to believe, what descriptive claims to agree with? — Pfhorrest

So I know that a vision is real regardless of distance when I can get agreement from others on its relative shape in space. I know that an object is real regardless of shape when I can get agreement from others on its relative spatial aspects over time. I know that an event is real regardless of physical aspects when I can get agreement on its relative temporal aspects in others’ experiences. And I know that an experience is real regardless of its time or duration when I can get agreement on its relative significance or value in relation to what it means. But I cannot know if meaning is real (ie. if matter or anything is real) regardless of how I experience it.

When I can reliably assert that an event is real, I can then relate that event to a collection of spatial aspects in an agreed temporal duration. By doing this, I reduce the event to its relationship with real objects, further strengthening the concept in my mind.

Likewise, with an experience in which there is no agreement on temporal aspects, we obtain agreement from others on its value aspects or significance in relation to what that experience means. This conceptualised experience can then be reduced to certain real events in relation to their significance, which can be further reduced to real objects that are then imbued with the significance of the experience. -

creativesoul

12.2kAll attribution of meaning consists of correlations drawn between different things. I would not pursue a question about the meaning of descriptive statements.

— creativesoul

I don't understand what you're trying to say. — Pfhorrest

Did you understand the first claim?

— creativesoul

You'll have to tell me if I understand you right. That sounds to me like you're saying all meaning is of the type meant by expressions like "clouds mean rain" and "smoke means fire": one thing signifies another thing, because of the correlation between those things. Is that what you mean by that claim? If so, what do you take statements that purport to describe reality to signify, or correlate with -- what do they mean? Or if you somehow object to asking that question, can you explain why? — Pfhorrest

Do you know what all attribution of meaning consists of?

Not one type.

Does that help? -

I like sushi

5.3kThis is what drew me to your website. I was going to ask if you’d tried to show how these relate.

I like sushi

5.3kThis is what drew me to your website. I was going to ask if you’d tried to show how these relate.

Hopefully we have a lot to discuss about how best to structure the current layout of philosophy in this ‘zoological’ manner :) -

creativesoul

12.2k...one thing signifies another thing, because of the correlation between those things...

Sometimes.

If so, what do you take statements that purport to describe reality to signify, or correlate with -- what do they mean? Or if you somehow object to asking that question, can you explain why?

What do statements about the world and/or ourselves mean?

Does that work for you? Is that close enough to your questions? -

creativesoul

12.2kWhat exactly about reason is in need of an explanation? — Pfhorrest

Everything. What is the minimum criterion that need be met prior to our assent that the candidate under consideration qualifies as a case of reason, or Reason, or...

What does all reason consist entirely of? -

Wayfarer

26.1kIf some ghost hunters manage to actually capture incontrovertible evidence for ghosts, for example, I'm not going to say "that's supernatural so it doesn't count", I'm going to look forward to the amazing scientific discoveries that are sure to follow from this newly-confirmed unexplained phenomenon. — Pfhorrest

Wayfarer

26.1kIf some ghost hunters manage to actually capture incontrovertible evidence for ghosts, for example, I'm not going to say "that's supernatural so it doesn't count", I'm going to look forward to the amazing scientific discoveries that are sure to follow from this newly-confirmed unexplained phenomenon. — Pfhorrest

There's Jacalyn Duffyn's research into miraculous cures associated with Catholic saints. (Duffyn says she remains an atheist and that she hasn't been persuaded by this research to believe in God, but she does acknowledge that the evidence is incontrovertible that these cases lack a scientific explanation, and she's working off a large set of cases.)

Another class of evidence is that concerning children who recall their previous lives. One Ian Stevenson researched many thousands of cases of children who recalled their past lives; there's a recent editorial on him here. He wrote many books on his research including Where Reincarnation and Biology Intersect which contains many cases where children were born with birthmarks and physical deformities that seemed to be associated with their manner of death from their recalled previous lives. And he too had a pretty large data set (~ 2,700 cases, not counting thousands more that had been rejected.)

Belief in rebirth is a cultural taboo, and most people will refuse to consider it, and I'm not saying anyone ought to believe it. But these cases exist, and there are many other cases of studies of paranormal phenomena that defy naturalistic explanation. Stevenson tried to approach the question empirically but overall he was maligned, not because of his methodology, but because of the subject matter. Philosophically, that is the main point.

And besides, what makes you think modern scientific method is universal? It rests on certain (often unstated) axioms, which rule in and out certain kinds of lines of research. After all modern naturalism was founded on the Enlightenment conviction that the Universe is basically dumb stuff, matter~energy developing in accordance with physical forces; what if it's not? What would the 'scientific evidence' be for that?

Many people in modern ages therefore place their notion of God as something entirely beyond that kind of experiential import, which then puts it into the category of supernatural as I mean it, about which we can only believe one way or another on faith. (Look at all the agnostics and theists on this very forum who insist that atheism also be taken on faith, because God as they mean it is beyond the proof or disproof.) — Pfhorrest

There is the evidence of kinds that can't be captured in peer-reviewed literature, especially in light of the above-mentioned convictions.

It is certainly true that God is beyond empirical evidence. Actually I am of the view that religious literalism, such as creationism and intelligent design, misunderstands this point, and so envisages God as a kind of 'uber architect'. Scientific atheists such as Dawkins make the opposite error of believing that the existence of God can be disproved by science - but in so doing, they're arguing for the non-existence of something which those who are not fundamentalists never believed in the first place (a 'straw god', so to speak).

How I see it is that scientific reason has a range, and there are domains beyond its range, also therefore beyond its methodological scope. (Actually, the nature of number is one of them.)

The crucial point is that the domain of phenomena, the domain which is amenable to empirical investigation, is what 'the transcendent' is transcendent in relation to. So, from the viewpoint of the empiricist, it is certainly true that 'nothing exists beyond what can be known by science', but that is, again, a methodological presumption, or a statement about this mode of understanding, rather than a statement about reality as a whole. To take is as the latter is, again, to cross over from methodological to metaphysical naturalism (which is near to positivism, in a general sense.)

Getting the idea of what 'the transcendent' means can be extraordinarily difficult (although it's not always). It appears to the sensory mind as mere nothing, but the mystics speak of 'luminous emptiness' or 'the nothing which is everything'. These expressions are widespread enough, being found in every culture and historical period, to indicate they have a real reference, although it's not a referent that can be known by science. (I don't expect you to accept that, but as someone sympathetic to mysticism I am obliged to point it out.)

reason itself does not have a natural explanation

— Wayfarer

I'm not sure what you mean here. What exactly about reason is in need of an explanation? "How did humans come to be able to use reason?"? That is, as you say, not a philosophical question, but a biological one, and evolutionary explanations work just fine there. — Pfhorrest

There is a very interesting and completely mainstream philosophical argument called 'the argument from reason'. I don't know if I will try and paraphrase it here, which would take at least 500-750 words. Maybe I'll create an OP, now you're around. It was recently revived by C S Lewis, and then by Victor Reppert. But rather than lay the whole argument out, I will make a couple of peremptory remarks.

The first is, that we can't explain reason, as 'reason is what explains'. I mean, from your remarks, you seem to think it's obvious that rationality can be understood as an adaptation. But the problem is, it sells reason short. How can I illustrate that? I have a really succinct quote from Descartes, to wit:

if there were machines that resembled our bodies and if they imitated our actions as much as is morally possible, we would always have two very certain means for recognizing that, none the less, they are not genuinely human. The first is that they would never be able to use speech, or other signs composed by themselves, as we do to express our thoughts to others. For one could easily conceive of a machine that is made in such a way that it utters words, and even that it would utter some words in response to physical actions that cause a change in its organs - for example, if someone touched it in a particular place, it would ask what one wishes to say to it, or if it were touched somewhere else, it would cry out that it was being hurt, and so on. But it could not arrange words in different ways to reply to the meaning of everything that is said in its presence, as even the most unintelligent human beings can do. The second means is that, even if they did many things as well as or, possibly, better than anyone of us, they would infallibly fail in others. Thus one would discover that they did not act on the basis of knowledge, but merely as a result of the disposition of their organs. For whereas reason is a universal instrument that can be used in all kinds of situations, these organs need a specific disposition for every particular action. — Rene Descartes

Bear in mind, that was written in 1630. And notwithstanding the huge progress in AI, this remains true. (As it happens, I worked in an AI startup for three months, as a tech writer, a year ago, and the capabilities of AI are still strictly mechanical. No AI system knows why it does anything, or really understands what it is outputting; it is not actually intelligence as such, but a vast interconnected network of devices. I have some amusing anecdotes which testify to this.)

I've already said too much, I sit down to write a brief reply and the next minute I've written a few hundred words. Thanks again for your input, by the way the diagram is excellent, although predictably I will say it's missing a piece, but we'll take that up again later. ;-) -

Pfhorrest

4.6kI am winding down for bed so this will be brief but then I’ll be mostly away for a few days so I want to reply with something.

Pfhorrest

4.6kI am winding down for bed so this will be brief but then I’ll be mostly away for a few days so I want to reply with something.

Mostly I think you’re reading too much of your impression of a materialist into my philosophy when those elements aren’t there. I’m not familiar with the evidence about the paranormal things you describe and I’m skeptical about claims regarding them but on philosophical principle I don’t object to claims about such things, since they are in principle amenable to investigation and it’s just a contingent question as to how that investigation will turn out. Paranormal is not the same as supernatural.

I agree that the physical sciences have a limited domain, but that domain is only limited to the description of reality. Other kinds of activities, like prescribing morality, are outside the dominant of physical science. But that’s because such science says nothing about them, so you’re not going to end up in conflict with science about them. But if you’re saying something is real, but in a sense that we cannot tell the difference between this world where it’s supposedly real and a world where it wasn’t — which is all I mean by empirical — then it seems to me you’re not actually saying anything about reality at all. Maybe you’re emoting? I’ve got no problem with theological noncognitivism so long as it’s self-aware and not confused with cognitive claims.

On which note, I don’t think mystical experiences like you describe really count as evidence for any kind of descriptive claim about reality, because I’ve been a frequent recipient of them, a profound feeling of empty meaningfulness, as in feeling meaningfulness but not about anything in particular or for any reason, just an overwhelming feeling of awe, oneness, connectedness, etc, accompanying an otherwise mundane experience. I think such experiences are very important in a meaning of life way I’ll get into later (or just read my final essay), but insofar as it matters for figuring out what’s real or not, I recognize them for just the feelings that they are, not as some kind of glimpse into a deeper reality. (I feel here kind of like a Tolkien elf telling mortals that magic isn’t real, while having just done something that those mortals call “magic”).

As for that Descartes quote, I’ll just say that it begs the question. I know that AI isn’t there yet still, but it’s presumptive to declare that it is in principle impossible. That’s something we could have a much longer argument about, maybe in another thread. -

Possibility

2.8kThere is a paper by the French philosopher of science, Michel Bitbol, It is never known but is the knower: consciousness and the blind spot of science which elaborates this point from a contemporary perspective. — Wayfarer

Possibility

2.8kThere is a paper by the French philosopher of science, Michel Bitbol, It is never known but is the knower: consciousness and the blind spot of science which elaborates this point from a contemporary perspective. — Wayfarer

Interesting read - a much better way of explaining what I’ve alluded to in my response to the ‘Objects of Reality’ question here. -

Wayfarer

26.1kI think you’re reading too much of your impression of a materialist into my philosophy when those elements aren’t there — Pfhorrest

Wayfarer

26.1kI think you’re reading too much of your impression of a materialist into my philosophy when those elements aren’t there — Pfhorrest

It's not your philosophy in particular, but I do acknowledge that this style of criticism is my focus, so I apologize if it's annoying. But it's the zeitgeist I'm criticizing, the spirit of the age - what happens when you take God out of the picture, and interpret the world through the perspective of science, where science is the arbiter of what is real. And again, that is vastly preferable to theocracy, I would not like to live in a theocratic culture and firmly support the benefits of living in the secular state. But let's remember what 'secular' is - it is 'affairs of state'. It is making the trains run on time, providing public education, improving medicine and science, and other things, many of which are beneficial. I think your philosophy is a splendid example of what philosophy in the secular context should be, and I really think you should be teaching it. But those who are aware of a kind of spiritual lack (includes myself) are seeking something other than, or more than, what secular culture provides. And those who make of secularism a philosophy, are sometimes trying to make a religion out of it. (By way of footnote, Auguste Comte, founder of social science and positivism, started a 'religion of humanity', a secular religion, which today, oddly, only has any real presence in Brazil.)

I agree that the physical sciences have a limited domain, but that domain is only limited to the description of reality. Other kinds of activities, like prescribing morality, are outside the dominant of physical science. — Pfhorrest

Limited only to the description of physical reality, with the tacit assumption that reality is physical. Again, a splendid assumption to have - for scientists and engineers. But not necessarily any kind of final truth.

And again, don't take that as a criticism of you in particular - it's one of the quandaries of the time we live in. Because science has taken over that role of 'umpire of reality', and because the reality science assumes is devoid of meaning, then meaning is provided by the individual - hence subjectivism and relativism. This is the subject of one of the seminal texts of moral philosophy of our day, After Virtue, Alisdair McIntyre (which incidentally I learned of on a forum, although not this one.)

But the point reflects the division of quantity and quality, is and ought - Hume's 'is/ought' problem in a nutshell. And I maintain that one purpose of philosophy is to try to efface that division. In pre-modern philosophy, 'the sage' was always one with a vision of 'what is' that also implied 'what one ought to do'. You will find that in nearly all classical philosophy, east and west.

I don’t think mystical experiences like you describe really count as evidence for any kind of descriptive claim about reality — Pfhorrest

The mystics I'm thinking of, are the Christian, Hindu and Buddhist mystics. Probably out-of-scope for this forum.

A much better way of explaining what I’ve alluded to in my response to the ‘Objects of Reality’ question — Possibility

Still, yours is a very good analysis, and well-written. But Michel Bitbol (another person I was alerted to through forums, this one in this case) is a very interesting modern philosopher and well worth studying. -

Pfhorrest

4.6k

Pfhorrest

4.6k

You'll note that I don't say anything at all about whether God exists until the very last chapter of my book. It's an open question, and most of the book is about how to go about answering questions. My philosophy isn't built around an absence of God; rather, the conclusion that nothing that would count as God is likely to exist is a consequence that falls out of more general questions.'m criticizing, the spirit of the age - what happens when you take God out of the picture — Wayfarer

Limited only to the description of physical reality, with the tacit assumption that reality is physical — Wayfarer

Where by "physical" I mean "empirical" and by "empirical" I mean "you could tell the difference between a world where it's true and a world where it's not". Non-physical things, by such definition, make no noticeable difference. Conversely, anything that makes any noticeable difference in the world is empirical for that reason, and so counts as physical by this definition.

because the reality science assumes is devoid of meaning, then meaning is provided by the individual - hence subjectivism and relativism [...] Hume's 'is/ought' problem in a nutshell — Wayfarer

You'll note that I am very much against subjectivism and relativism too. I think we agree that that is a major fault in modern society, that assumes that "is" is the only kind of question that has objective answers, and "ought" is all sentiment. I agree with the is/ought distinction inasmuch as I don't think "oughts" are reducible to "is", but I think Hume is completely wrong about how to deal with "oughts", and that there is a completely analogous way to treat them as objective, grounded in phenomenal experience, open to criticism, but not destroyed by infinite regressions -- just like the physical sciences treat reality.

Me too.The mystics I'm thinking of, are the Christian, Hindu and Buddhist mystics. — Wayfarer

Welcome to The Philosophy Forum!

Get involved in philosophical discussions about knowledge, truth, language, consciousness, science, politics, religion, logic and mathematics, art, history, and lots more. No ads, no clutter, and very little agreement — just fascinating conversations.

Categories

- Guest category

- Phil. Writing Challenge - June 2025

- The Lounge

- General Philosophy

- Metaphysics & Epistemology

- Philosophy of Mind

- Ethics

- Political Philosophy

- Philosophy of Art

- Logic & Philosophy of Mathematics

- Philosophy of Religion

- Philosophy of Science

- Philosophy of Language

- Interesting Stuff

- Politics and Current Affairs

- Humanities and Social Sciences

- Science and Technology

- Non-English Discussion

- German Discussion

- Spanish Discussion

- Learning Centre

- Resources

- Books and Papers

- Reading groups

- Questions

- Guest Speakers

- David Pearce

- Massimo Pigliucci

- Debates

- Debate Proposals

- Debate Discussion

- Feedback

- Article submissions

- About TPF

- Help

More Discussions

- Elemental philosophy, on teaching philosophy to kids, from protophilosophy upwards

- Dubious Stance: "Philosophy Questions. Religion Preaches. I Choose Philosophy."

- Are most solutions in philosophy based on pre-philosophical notions/intuitions? Is Philosophy useful

- Philosophy 101, 8 minute lectures pertaining philosophy.

- Would a “science-based philosophy” be “better” than the contemporary philosophy?

- Other sites we like

- Social media

- Terms of Service

- Sign In

- Created with PlushForums

- © 2026 The Philosophy Forum