-

frank

19kIt's not so much capitalism that unleashed human potential. It's money. Read Jack Weatherford's book: The History of Money. He explains why money and banking transformed human life.

frank

19kIt's not so much capitalism that unleashed human potential. It's money. Read Jack Weatherford's book: The History of Money. He explains why money and banking transformed human life.

So even socialism without money (which is what the Bronze Age palace economy basically was) would take us down into a static existence. There would still be volatility, but not coming from the waves in the economic system itself, but from drought and war. -

boethius

2.7kIt's not so much capitalism that unleashed human potential. It's money. Read Jack Weatherford's book: The History of Money. He explains why money and banking transformed human life. — frank

boethius

2.7kIt's not so much capitalism that unleashed human potential. It's money. Read Jack Weatherford's book: The History of Money. He explains why money and banking transformed human life. — frank

But you can say the same thing about writing, or metal work, or the wheel, or essentially any technology required for our economy to work and the history of it's development. Money is a useful technology and has an interesting history, but it's one out of many such technologies. -

frank

19kMoney is a useful technology and has an interesting history, but it's one out of many such technologies. — boethius

frank

19kMoney is a useful technology and has an interesting history, but it's one out of many such technologies. — boethius

My point was that much of the benefits we sometimes think of as capitalist in origin are really just a side effect of the use of an abstract medium of exchange.

I'm not poo pooing the wheel. -

boethius

2.7kI'm not poo pooing the wheel. — frank

boethius

2.7kI'm not poo pooing the wheel. — frank

Yes I agree with your point about not equating money to capitalism, but your phrasing "It's not so much capitalism that unleashed human potential. It's money." seems to put special emphasis on money as unlocking human potential; seems a very ambitious statement relative other critical technologies (unless the author is saying the same thing about them too). Since this thread is on socialism and communism, I'd be interested if the author you cite, writing on the history of money and capitalism, is aware that, at least as how you phrase it as "unleashing human potential", seems an example of the fetishism Marx was talking about; does the author deal with this idea? -

frank

19kSince this thread is on socialism and communism, I'd be interested if the author you cite, writing on the history of money and capitalism, is aware that, at least as how you phrase it as "unleashing human potential", seems an example of the fetishism Marx was talking about; does the author deal with this idea? — boethius

frank

19kSince this thread is on socialism and communism, I'd be interested if the author you cite, writing on the history of money and capitalism, is aware that, at least as how you phrase it as "unleashing human potential", seems an example of the fetishism Marx was talking about; does the author deal with this idea? — boethius

It's not a history of capitalism. -

180 Proof

16.5kVLTTP ...

180 Proof

16.5kVLTTP ...

My argument against capitalism is that progress in human development doesn't happen fast enough, fairly enough, or securely enough, and ties us all into a system of endless toil and precarity. — jamalrob

Plutonomics?

My view of capitalism, or just modernity in general that would include soviet communism, is that it is akin to ever increasing doses of cocaine; there are short term "good effects" but at a massive long term cost; the short term "life improvement" is an illusion. If you have ever argued with someone in the honey moon phase of cocaine or other stimulants who think it's great and made their life better, you get the exact same structure of argument as the myth of progress (it's seems pretty good right now bro) and my argument against capitalism and modernity is exactly the same as you will be trying to make cocaine.

Yes, productivity has gone up (just like cocaine) but if it a dynamic that moves towards ecological collapse (cardiac arrest) then the goodness of this productivity is wholly illusionary (just like cocaine addiction).

[ ... ]

I do not view improvements that are not sustainable as improvements, ... — boethius

Entropology?

I also haven't considered myself to be a libertarian socialist since around 2015, or since whenever I read Mariana Mazzucato's book, The Entrepreneurial State. — Maw

:cool: -

Jamal

11.8kThat's the matter I'm taking issue with. I don't see how it makes any sense to say something is an improvement "in itself" where, by that, you mean "when ignoring certain other factors inextricably connected with it" . — Isaac

Jamal

11.8kThat's the matter I'm taking issue with. I don't see how it makes any sense to say something is an improvement "in itself" where, by that, you mean "when ignoring certain other factors inextricably connected with it" . — Isaac

It does make sense. If I couldn't buy a washing machine (income) and didn't have access to a launderette (infrastructure or economic development, not part of the HDI but significant for my example), it would make my life worse. To measure things at all requires the isolation of specific metrics. The ones we choose to measure here are based on the things we all value; they are factors that contribute to freedom, opportunity, health, leisure, and so on.

Here's a contrived example. We value education. It's usually better to go to school than not to go to school, even if there's a risk that you will be run over by a car on the way there. But, you may ask, what if going to school always leads to traffic-related premature death: surely that means going to school does not represent an improvement over not going to school? Of course not: it just means we need to do something about the traffic or the location of the school (or whatever).

But, you may further ask, what if going to school inevitably leads to traffic-related premature death? I.e., what if the increased HDI, and economic growth more generally, inevitably leads to environmental catastrophe and social breakdown? Well, that hasn't been shown.

So maybe this is all just about the choice of words. I think that @boethius could make his case more strongly by saying, yes, there have been improvements, but those improvements have been achieved unsustainably, and continuing to pursue them will lead to terrible consequences. And then we could argue about that, which is the substantial disagreement.

Maybe you can now see what I've been doing here. I have not really been arguing directly over that substantial disagreement, but trying to reveal what @boethius's choice of words, his choice to actually deny demonstrable improvements, says about his position more generally. -

Isaac

10.3k

Isaac

10.3k

OK, I get where you're coming from. Your third example is really what I'm thinking about, where some other factor in inextricably linked and so to ignore it in any judgement of 'improvement' would be perverse.

You're saying that the preference of the householder for having a washing machine has been shown (and so is a reasonable factor to include in the judgement), but the associated environmental and social problems have not (and so it is reasonable to exclude them from the judgment)?

I think that the case for environmental problems associated with mass production of white goods is almost unarguable. I grant it's not 100%, but then neither is the preference of the householder (do they really prefer it, how do we know what they really think, etc...). There's always room for doubt, but that goes both ways.

So I get what you're trying to say, but I disagree that problems are not inextricably linked to the benefits. I think they are, and I think the prevailing scientific opinion backs me up on that. The world simply has a finite supply of energy, materials and social resources (people who are prepared to do stuff you don't want to). Any benefit which relies on those thing, beyond the rate at which they can be replenished, is de facto coming along with a cost which cannot reasonably be ignored. -

Jamal

11.8kYou're saying that the preference of the householder for having a washing machine has been shown (and so is a reasonable factor to include in the judgement), but the associated environmental and social problems have not (and so it is reasonable to exclude them from the judgment)? — Isaac

Jamal

11.8kYou're saying that the preference of the householder for having a washing machine has been shown (and so is a reasonable factor to include in the judgement), but the associated environmental and social problems have not (and so it is reasonable to exclude them from the judgment)? — Isaac

No that's not my position. My position is that there have been associated problems, and that recent climate change and other environmental problems are caused by economic growth, but that the two things are not inevitably linked, at least not to the detriment of human beings. I believe that the primary aim of policy should be to improve people's lives and that the best way to do that while also solving the associated problems is more economic growth, which will allow us all to switch to cleaner energy, find more resources and use existing ones better, and also allow particularly vulnerable populations to protect themselves from change. In a nutshell, an economically growing humanity can clean up after itself, as is evident when we look at history.

There are several commentators who argue this case from across the political spectrum, but unfortunately many of them go too far in celebrating the wonders of capitalism. This is understandable: capitalism might not be the best way to solve these problems, but so far it is the best way we've found to achieve quick growth, and given the choice between capitalism and Malthusian de-growth, I'll take the former, along with the millions who buy washing machines as soon as they can afford them.

This is more or less where I'm coming from: https://www.neweurope.eu/article/the-no-growth-prescription-for-misery/

Obviously if I'm going all-out to argue for this I'll have to do a lot more, but I'm not sure I want to get into one of those statistics-drenched debates, and I hadn't really intended to get into it when I first entered this discussion--so if I decide to chicken out, I apologize. -

I like sushi

5.4kClimate change and environmental issues are serious problems - hopefully that can be agreed upon by all (give or take with varying degrees of severity).

I like sushi

5.4kClimate change and environmental issues are serious problems - hopefully that can be agreed upon by all (give or take with varying degrees of severity).

In regards to the OP in what fashion is this going to affect or effect any possible transition from a more capitalistic geopolitical world into something approximating a ‘better’ future for all?

Whilst many may reel against the idea of giving African households, and the means offload domestic duties, there is the negative impact of doing so on African society at large - the empowerment of women. You will generally find that poverty is an extremely potent motivator so those having a faction if time freed up generally look to improve their situations (through education/training and/or adding to machines/equipment that can free up more time). The knock-on effect of women having greater freedom is they are then able to help educate their children better and take control of how many children they have (because healthcare has slowed down child mortality).

Generally speaking the ‘western world’ (basically meaning Europe, North America and other countries o a similar economic/technological level) needs to lead the way in terms of creating sustainable, and affordable, energy sources.

Regardless, people will have more freedom when they have easier access - money generally allows people wiggle room to improve their situation and step up. Mobile phones are hugely important and can/do help people at the bottom broaden their opportunities. Sadly I don’t think we’ve any serious idea about what kind of impact the internet will have: let alone what impact it already has had.

I’m more worried about the future of less developed countries and their ability to produce food. The climate is certainly changing and this means some areas will not be able to produce as much food - such crisis in certain areas around the world could (and probably will) be hugely disruptive.

Another worry is that I believe the ‘western world’ is going to be hit much harder as the rest of the world catches up - simply because people feel a slight pinch as a chasm where in other parts of the globe such financial difficulties are the norm.

Some guidance from the OP may be helpful at this moment? I don’t know exactly what area they wished to focus on, but I’m sue we cannot cover everything from trade, education, environment, climate change, geopolitics, social action, media influences, technological advances (in various areas) and the power of private companies over governments, not to mention the potential positive and negative effects of all of these. -

I like sushi

5.4kI wouldn’t call it chickening out. If there is literally no common point of agreement it’s going to be little more than finger-pointing and unsubstantiated accusations.

I like sushi

5.4kI wouldn’t call it chickening out. If there is literally no common point of agreement it’s going to be little more than finger-pointing and unsubstantiated accusations.

I stepped aside for those reasons initially. I’m more interested in what the OP has to add if anything? If nothing I doubt I’ll do much more than watch from now on. -

Jamal

11.8kWe've certainly strayed a long way off topic. I forgot it was about the "leap from socialism to communism."

Jamal

11.8kWe've certainly strayed a long way off topic. I forgot it was about the "leap from socialism to communism." -

boethius

2.7kIt does make sense. If I lost my washing machine (income) and didn't have access to a launderette (infrastructure or economic development, not part of the HDI but significant for my example), it would make my life worse. To measure things at all requires the isolation of specific metrics. The ones we choose to measure here are based on the things we all value; they are factors that contribute to freedom, opportunity, health, leisure, and so on. — jamalrob

boethius

2.7kIt does make sense. If I lost my washing machine (income) and didn't have access to a launderette (infrastructure or economic development, not part of the HDI but significant for my example), it would make my life worse. To measure things at all requires the isolation of specific metrics. The ones we choose to measure here are based on the things we all value; they are factors that contribute to freedom, opportunity, health, leisure, and so on. — jamalrob

This is exactly what @Isaac is saying in the what you quoted. I'm pretty sure he doesn't disagree that a metric can be measured, but to say that it is therefore good or bad, the change requires extrinsic factors (an understanding of the system that isolated metric is apart of).

You cannot say an "to measure things at all requires the isolation of specific metrics" to the conclusion "therefore that metric has improved" and from there "therefore the system that metric is apart has improved", without more context (as well as a moral system from which to judge what is good and bad).

Which is exactly why you bring up yourself, "and didn't have access to a launderette": this is an extrinsic factor!

If we see laundry machine ownership is going down we need context to understand if this is good or bad, even from the perspective of just laundry. If people are replacing laundry machines with a more efficient laundromat service (new and cool uber for laundry) we may conclude "insofar as laundry is concerned, it's getting better", but again it's only a "judgement that it's good" if it excludes other extrinsic factors tied to laundry in general.

Now, if both laundry machines and laundry services are going down, you may say "well certainly that's bad" but again we need context. What if people were unnecessarily doing too much laundry and a campaign of awareness was able to decrease the laundry metric and we'd look at the decrease and say "this is great, the program is working, resources are being saved".

What if someone invents clothes that never have to be washed or can be just produced a new every time! Sure, doesn't seem plausible, but it's not plausible due to extrinsic factors, due to context, we must actually go and check this context.

Just as isolated metrics about a patient aren't sufficient to claim the "patient is improving", just like isolated metrics about a corporation finances isn't sufficient to claim "the company is improving".

If the context of all economic development is unsustainable, or comes at the cost of greater 1984 style tyranny, then, yes metrics have gone up and down, but there is no way to jump to the conclusion that "therefore things have improved". If you want to make a claim such as "life for most people has improved" isolating a part of "what life means" such as tracking a metric or two, doesn't get to that conclusion. The myth of progress gets to that conclusion through the various fallacies I have been deconstructing. -

Jamal

11.8kI've answered all this already. We choose to measure specific metrics because they're the things we value, the things we want more of. We favour them as being more important than other things. It's reasonable on this basis to describe their increase as improvements, and this doesn't entail ignoring the context.

Jamal

11.8kI've answered all this already. We choose to measure specific metrics because they're the things we value, the things we want more of. We favour them as being more important than other things. It's reasonable on this basis to describe their increase as improvements, and this doesn't entail ignoring the context. -

Isaac

10.3kMy position is that there have been associated problems, and that recent climate change and other environmental problems are caused by economic growth, but that the two things are not inevitably linked — jamalrob

Isaac

10.3kMy position is that there have been associated problems, and that recent climate change and other environmental problems are caused by economic growth, but that the two things are not inevitably linked — jamalrob

Yes, I did get that, I just didn't paraphrase it very clearly, my mistake.

I believe that the primary aim of policy should be to improve people's lives and that the best way to do that while also solving the associated problems is more economic growth — jamalrob

I disagree with this, I don't see how, on the face of it, more of the same could possibly be a cure for the problems the previous growth caused.

if I'm going all-out to argue for this I'll have to do a lot more, but I'm not sure I want to get into one of those statistics-drenched debates, and I hadn't really intended to get into it when I first entered this discussion--so if I decide to chicken out, I apologize. — jamalrob

I think you're right. It's not really what this topic is about, and I'm not sure I've time for a full-throated attack on growth either.

The relevant part of what we've been discussing though is this...

capitalism might not be the best way to solve these problems, but so far it is the best way we've found to achieve quick growth — jamalrob

I think this is more myth-building. Its the only way we've found because it's the only way we've really tried. That's not much to commend it. For a start, economic growth does not seem at all to depend on how capitalist a country is. Some very socialist economies are doing very well, some extremely free-market economies have done very badly. If the degree, or proportion, of capitalism in an economy does not correlate well with human development, it seems, on the face of it, quite unlikely that its capitalism that's responsible. -

Jamal

11.8kI disagree with this, I don't see how, on the face of it, more of the same could possibly be a cure for the problems the previous growth caused. — Isaac

Jamal

11.8kI disagree with this, I don't see how, on the face of it, more of the same could possibly be a cure for the problems the previous growth caused. — Isaac

There are several ways. For climate change, there are technological solutions, such as clean energy, and they require massive research and investment; and societies with highly developed infrastructure and commanding resources effectively can protect themselves from unwelcome changes. So both mitigation and adaptation can be achieved with growth. For other environmental problems, we can see the positive results in developed countries already, where e.g., pollution has been reduced.

It's not more of the same, but more and different.

I think this is more myth-building. Its the only way we've found because it's the only way we've really tried. That's not much to commend it. For a start, economic growth does not seem at all to depend on how capitalist a country is. Some very socialist economies are doing very well, some extremely free-market economies have done very badly. If the degree, or proportion, of capitalism in an economy does not correlate well with human development, it seems, on the face of it, quite unlikely that its capitalism that's responsible — Isaac

But you appear to agree that "it's the only way we've found", which is what I said (although I actually said "best way we've found so far") Otherwise sure, you're pretty much right here I think. I'm not arguing for capitalism but for growth. -

Isaac

10.3kthere are technological solutions, such as clean energy — jamalrob

Isaac

10.3kthere are technological solutions, such as clean energy — jamalrob

I don't disagree with technology, but I do think there's a big problem in the "growth to solve" argument when it comes to unknowns.

Past development wasn't undertaken and promoted by people who didn't care a fig about the consequences. It was undertaken and promoted by people who were (almost) completely unaware of the consequences. They went ahead anyway, and here we are with a very serious social and environmental crisis on our hands.

So the solutions you talk about obviously seem like solutions now. We're in the same situation now as the early fossil-fuel enthusiasts were in 200 years ago. What happens when we find out the Indium in solar panels causes devastating damage to microbes, the disruption to air streams caused by wind power results in damaging weather pattern changes, the habitat loss from converting to biodiesel is worse than the fossil-fuel it's replacing... These are all real concerns by the way, just not well researched enough to provide any concrete worries yet. The point is our optimism about growth blinds us to the historic fact that virtually everything we thought was going to be some brilliant development turned out to be shit, in terms of some (usually long-term) undesirable consequences.

What makes you so confident that, unlike almost every development in the past, today's 'solutions' won't just end up being tomorrow's problems? -

Jamal

11.8kSo the solutions you talk about obviously seem like solutions now. We're in the same situation now as the early fossil-fuel enthusiasts were in 200 years ago. What happens when we find out the Indium in solar panels causes devastating damage to microbes, the disruption to air streams caused by wind power results in damaging weather pattern changes, the habitat loss from converting to biodiesel is worse than the fossil-fuel it's replacing... These are all real concerns by the way, just not well researched enough to provide any concrete worries yet. The point is our optimism about growth blinds us to the historic fact that virtually everything we thought was going to be some brilliant development turned out to be shit, in terms of some (usually long-term) undesirable consequences. — Isaac

Jamal

11.8kSo the solutions you talk about obviously seem like solutions now. We're in the same situation now as the early fossil-fuel enthusiasts were in 200 years ago. What happens when we find out the Indium in solar panels causes devastating damage to microbes, the disruption to air streams caused by wind power results in damaging weather pattern changes, the habitat loss from converting to biodiesel is worse than the fossil-fuel it's replacing... These are all real concerns by the way, just not well researched enough to provide any concrete worries yet. The point is our optimism about growth blinds us to the historic fact that virtually everything we thought was going to be some brilliant development turned out to be shit, in terms of some (usually long-term) undesirable consequences. — Isaac

True, and yet...

Few things are more important.

What makes you so confident that, unlike almost every development in the past, today's 'solutions' won't just end up being tomorrow's problems? — Isaac

That's not exactly what I'd say. I'd say I'm confident that we can deal with the problems that come up. It's never absolutely certain but I think the alternatives to technological progress are immoral, unfair, dangerous. My attitude to the precautionary principle is, roughly, that if you know you can make a change for the better, and if it won't be outweighed by changes for the worse as far as you can tell, then there is no justification for failure to make that change. This is how we do it.

And it's important to point out that past developments have not just ended up being today's problems. They have been good in many ways.

There are exceptions, of course. Nuclear weapons, for example, which could end up being a really stupid idea. This does show that the technological cannot be separated from the political, but I don't think it should lead us to seek to slow down technological progress as such. -

frank

19kI'm not arguing for capitalism but for growth. — jamalrob

frank

19kI'm not arguing for capitalism but for growth. — jamalrob

Growth usually goes hand in hand with population growth. Countries that afford rights to women become reliant on immigration because women who aren't chained to childbirth avoid it.

So continued growth tends to be somewhat reliant on human rights violations somewhere, if not here.

Otherwise, growth is possible because we're coming out of a depression. Devotion to that is devotion to occasional mass suffering.

How do you hold to growth as inherently good? I think it just happens. It's not good or bad. -

I like sushi

5.4kLack of growth means less literacy, higher child mortality, larger families, and poorer healthcare. Of course places like the US and Europe will be relatively peachy, but elsewhere? War, famine, corruption and further exploitation - plus those other countries tend to have some pretty nice nature reserves that won’t be a priority for them when they’re mostly struggling to survive the day.

I like sushi

5.4kLack of growth means less literacy, higher child mortality, larger families, and poorer healthcare. Of course places like the US and Europe will be relatively peachy, but elsewhere? War, famine, corruption and further exploitation - plus those other countries tend to have some pretty nice nature reserves that won’t be a priority for them when they’re mostly struggling to survive the day.

Of course this may well be the death throes of the human species. I don’t think so though, but like all the other obstacles we’ve faced I believe in the resourcefulness of humanity. People are very vocal today - it’s something we should take as an encouraging sign. If everyone was simply rolling over waiting to die (as some folks actually profess) we’d already be finished.

For some reason my post sparked this digression. I didn’t bring up the environment or climate change; both of which are going to get worse before they get better. We’re currently in a damage limitation phase right now and financial clout should probably be directed toward areas that benefit these rather than merely treating the symptoms (ie. Educating young women as no.1 priority) not pumping resources into some one in a million shot that looks good but is both ineffective and could possibly exacerbate the situation. -

boethius

2.7kI've answered all this already. — jamalrob

boethius

2.7kI've answered all this already. — jamalrob

You haven't. My criticism is exactly the fallacy you continuously repeat such as in your next sentence:

We choose to measure specific metrics because they're the things we value, the things we want more of. — jamalrob

Yes, I get that your measuring things.

It's reasonable on this basis to describe their increase as improvements, and this doesn't entail ignoring the context. — jamalrob

This is your mistake. It is not reasonable to describe their increase as improvements in themselves, even less make the leap to "therefore things have improved generally" that "life has improved generally or for most people".

It does entail ignoring the context, that's exactly what it entails. You can only bestow a "moral satisfaction" about the metrics if you ignore the context, if you include the statement "all else being equal" (this is the catchall phrase to say exactly this: if we ignore anything in the context that might lead us to another conclusion, then we would conclude this metric going this way is a good thing) otherwise, the context can lead us to another conclusion.

If the growth comes at massive ecological costs in the future that are far more onerous than all the short term increases in the various metrics, then we can question that growth represents an improvement for humanity.

It's not something that can be resolved in principle, you actually have to go out and check. If you value sustainability then you need to actually go and checkup on the metrics that tell us something about sustainability and if the economic growth you find pleasing comes at an ecological cost you have to make an argument that it was worth it, the argument "I look at some metrics because I care about those metrics ... but I also care about a context out there ... but I don't bother to look at metrics representing that context" doesn't make sense.

If you don't look at ecological metrics: it's because you don't value the ecosystems! Otherwise, by your own logic you would look at metrics that inform us of the state of the ecosystem because you care about the ecosystem. If those metrics are going in a bad direction, you can no longer say "look at this growth, look how everything is going up, certainly a good thing". You need to make an argument that the trade-off is worth it, otherwise your argument is simply "if you only look at things that are going in a good direction then you conclude things are going in a good direction and we can assume will continue to do so".

You can't just throw in a patch-up that "ok, I care about other things too ... I just don't look at them closely ... but I'm sure things are ok over there and in the future". That's what your argument boils down to, a completely baseless assumption that whatever the costs have been, whatever they will be, we don't need to look at those costs closely.

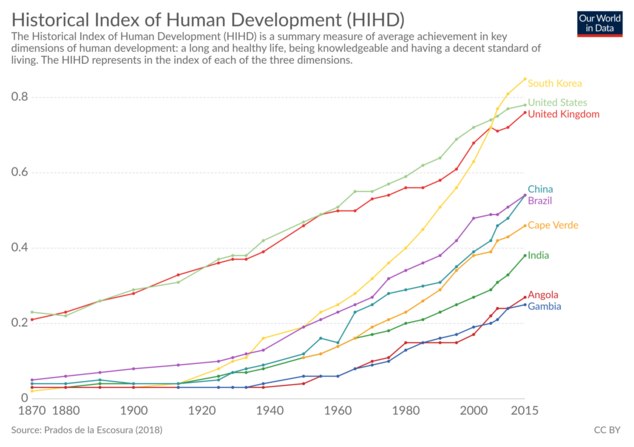

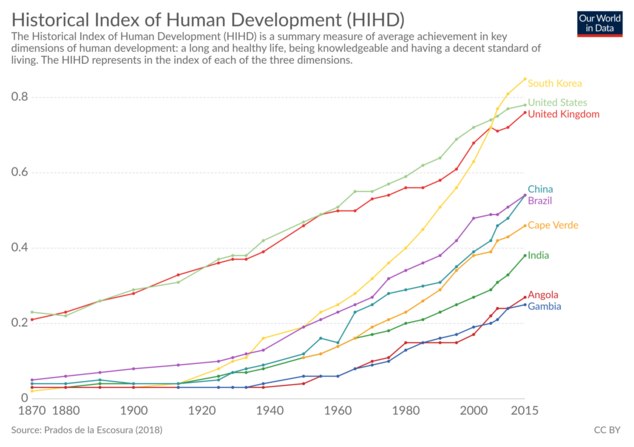

You throw up a graph of growth as I'm sure you've been itching to do as soon as you sense the myth of progress has stood it's ground. But you don't put up a graph of "level of free speech in China" of a graph of "bio-diversity" or "a graph of global forest cover" or "a graph of cultivatable land" or "a graph of remaining seed diversity" or "a graph of ground-water stores" or "a graph of top-soil". You simply assume, if these really are problems, that we'll solve those problems. This is an empirical claim and requires an empirical investigation to know anything about. There are physical limits to what we can do.

However, if industrialization is inherently unsustainable -- that it's industrialization, whether capitalist or socialist or a mix of the two, that has caused the ecological crisis in a physical "cause-effect" relationship (the actual physical objects that make-up industrial civilization) -- then it's simply not reasonable to say "well, more of the same will certainly cure the disease it's causing". Maybe it can! But you need very powerful arguments to convince someone more of what's making them sick is actually going to cure them.

If industrial civilization is not sustainable, you can put up as many graphs as you want showing things, that I agree "all else being equal" are good things, but if the system those metrics are describing is not sustainable then all those metrics are going to crash (that is what not-sustainable means) so not only will you lose the things you haven't bothered to throw up graphs about you'll also lose those things you do like looking at graphs about. You can argue "ok, things may crash for future generation, sooner or later, don't really care; I value people today and an industrial way of life for those people", then your argument is sound, but what follows it that it's not compelling to someone who does value future generations.

And there is an alternative: non-industrial technological civilization, meaning local production and consumption -- which can include doctors, literacy, democracy, low infant mortality, longevity -- but with the critical difference that it can be sustainable and the critical problem that it is a very radical change. However, that it's a radical change and politically difficult to implement (departs from the industrial status quo) is not a counter argument if the thesis that industrialization (large infrastructure with globally integrated material flows) is not sustainable, is correct; it becomes inevitably the only option (again, that's what non-sustainable means), the only questions are "do we get there at all" and "how much damage do we let industrialization do to the planet before making these changes". In other words, if industrialization is not sustainable then we have taken a wrong turn and the further we go down that path the worse off we are. -

Saphsin

387I think both of us may be among the small minority on the Left on de-growth here. But I also think that not only is de-growth undesirable, but that it is politically impossible, hard to make sense of it as a policy agenda anyone is crafting and implementing. When I look at what is described when people mean by de-growth, you have to practically abolish the global market economy as it is to make it happen. They should just admit that is what they're advocating instead of being roundabout. (I personally think it's delusional to think it'll take only a few decades to get to socialism, we have to start off with deeper structural reforms of global capitalism. Whether you believe in revolutions or not, it's the kind of goal that takes a lot of steps. Not a current solution to climate change.)

Saphsin

387I think both of us may be among the small minority on the Left on de-growth here. But I also think that not only is de-growth undesirable, but that it is politically impossible, hard to make sense of it as a policy agenda anyone is crafting and implementing. When I look at what is described when people mean by de-growth, you have to practically abolish the global market economy as it is to make it happen. They should just admit that is what they're advocating instead of being roundabout. (I personally think it's delusional to think it'll take only a few decades to get to socialism, we have to start off with deeper structural reforms of global capitalism. Whether you believe in revolutions or not, it's the kind of goal that takes a lot of steps. Not a current solution to climate change.) -

Saphsin

387I used to be attracted to Anarchism/Anarcho-Syndicalism because of its theoretical flexibility (as what initially seemed to me at least) and rejection of Stalinism. I thought the message was "yes Soviet & Chinese Communism led to economic development, but authoritarian regimes aren't acceptable" so one of the key questions I've always been interested in was democratic economic development, examples around the world of how to pursue both at once. And in the process, I realized, that a lot of these types of socialists say "yes to economic development, no to authoritarianism & capitalist exploitation", but don't actually care all that much about economic development, or at least they're not willing to see that the local-oriented projects they're inspired by won't realistically be used as models to improve the lives of most people living on this planet.

Saphsin

387I used to be attracted to Anarchism/Anarcho-Syndicalism because of its theoretical flexibility (as what initially seemed to me at least) and rejection of Stalinism. I thought the message was "yes Soviet & Chinese Communism led to economic development, but authoritarian regimes aren't acceptable" so one of the key questions I've always been interested in was democratic economic development, examples around the world of how to pursue both at once. And in the process, I realized, that a lot of these types of socialists say "yes to economic development, no to authoritarianism & capitalist exploitation", but don't actually care all that much about economic development, or at least they're not willing to see that the local-oriented projects they're inspired by won't realistically be used as models to improve the lives of most people living on this planet.

I had a discussion with this fellow anarchist once about my admiration for what the Costa Ricans achieved, they abolished their military and developed a welfare-state capitalist industrialization in combination with worker cooperatives. Not perfect, but we could learn from it as a model for third world development that's preferable to other countries who pursued economic growth in very authoritarian ways. And I was met with dismissal. And that's when I abandoned anarchism.

I guess I call myself a socialist. The term "Democratic Socialism" sounds nice. Others on the Left accuse that label of being just an ambitious form of social democracy, but that's definitely not right with respect to my views. -

boethius

2.7kWhen I look at what is described when people mean by de-growth, you have to practically abolish the global market economy as it is to make it happen. — Saphsin

boethius

2.7kWhen I look at what is described when people mean by de-growth, you have to practically abolish the global market economy as it is to make it happen. — Saphsin

The issue is "what is good growth" and "what is bad growth". This requires an understanding of the system and where it's going but also a moral theory to be able to decide what's good and bad about where it's going; with an understanding of the economic-ecological system as it exists today and a moral theory it is then also possible to decide what is feasible and justifiable to do about it.

De-growth of globalized industry while growing local production, from the perspective of most people, is actually higher growth in terms of more activity, more things to do; if there is suddenly no mass imports made with slave-labour from China this is going to create room for local fabrication of a lot of things; an activity boom in most places importing from China (perhaps a total collapse of the Chinese economy, but overall more activity).

The core problem with "free-trade is always good" is that it does not account for the ecological costs of the infrastructure and ecological cost of the energy spent to physically trade globally nor the political cost of being dependent on a potentially coercive force (i.e. economists who present free-trade as "efficient" without considering the negatives, are just propagandists -- they are certainly aware the negatives can outweigh the positives, they just choose to ignore reality to fool their gullible students).

For a very large amount (though not all) of products, if you perform an an analysis where the negative externalities are internalized, suddenly it is not at all clear-cut that local production is not-competitive. So why not internalize those costs?

The only argument for not internalizing the cost of negative externalities is:

1. deny such negative externalities even exist (which is not an argument against the principle that negative externatilities should be internalized, just a coping mechanism for being unable to think critically when confronted with empirical evidence one is in denial as well as existing protection from negative externalities that one does not want removed) or

2. not valuing future generations that are most affected by those negative externalities (nor any poor person today affected by those externalities). This is a sound argument to not internalize externalities, but it is not compelling to people who do care about future generations and the poor.

3. society has no right to protect itself from negative externalities from individuals and companies (there is so many problems with this I'll need to make another post if people don't see the obvious fundamental contradictions).

Now, if negative externalities (ecological, social and political) are internalized (which is a case-by-case empirical question requiring empirical investigation), and a product is still competitive being centrally produced, I have no argument against it. For instance, if computer chips simply can't be made locally and all the pollution externalities are internalized into the cost, I have no problem with a centralization of this process. However, if you imagine a world where only things like computer chips or similar complexity are being transported globally, this is a massive reduction in global transport: yes, basically dismantling what globalize industry as we know it today.

A regulated market is trivially easy to render sustainable: you just enforce internalization of costs. It's also not even that disruptive to do this to most people, life improves without those negative externalities (that's why it's negative; the myth of progress is the idea that negative externalities are somehow good for you or intrinsically tied to good things). Who it's not good for are the economic elite who's wealth is tied to global scale infrastructure and material flows.

Now, I agree that the first step is social democracy, we need government able to regulate in the interests of people. But I disagree (with Marx) that capitalism will fail resulting in a socialist uprising that then results in communism. Capitalism (laws dominated by capital rather than people to allow those profitable negative externalities to continue; i.e. "money should be equal to votes, ideally directly but failing that through unconstrained ability for money to influence politics") will fail, in terms of internal contradictions, due to ecological collapse (something that has been revealed empirically, not knowable in principle), and if we want to avoid ecological collapse we need to do something about it before capitalism collapses due to ecological collapse, not afterwards.

And I also agree that part of this step is distribution of wealth (social safety net) so that people aren't subsistence wage slaves and have time to think about global issues and future generations and be able to review what really are negative externalities and how best to internalize those costs.

Vis-a-vis the OP, if communism results from this process it is not because of the failure of markets and revolution, but because enforcing negative externalities in a reasonable way simply makes local production more and more competitive until (most people) are living in relatively small communities and are no longer alienated and, through these direct relationships, money is no longer the principle medium of relation (might still be around, just not a dominant force). -

Saphsin

387Modern capitalist countries will dip into a depression and harm people’s lives & stifle social development without continuous economic growth, that’s how the market economy works. If you don’t like how it works, we can debate about an ideal future society to aspire towards. But we’re not playing some Sims City video game where you pick and choose your designs of society, you have to deal with institutions in the current existing world in order to reorient and change the established order step by step.

Saphsin

387Modern capitalist countries will dip into a depression and harm people’s lives & stifle social development without continuous economic growth, that’s how the market economy works. If you don’t like how it works, we can debate about an ideal future society to aspire towards. But we’re not playing some Sims City video game where you pick and choose your designs of society, you have to deal with institutions in the current existing world in order to reorient and change the established order step by step.

Welcome to The Philosophy Forum!

Get involved in philosophical discussions about knowledge, truth, language, consciousness, science, politics, religion, logic and mathematics, art, history, and lots more. No ads, no clutter, and very little agreement — just fascinating conversations.

Categories

- Guest category

- Phil. Writing Challenge - June 2025

- The Lounge

- General Philosophy

- Metaphysics & Epistemology

- Philosophy of Mind

- Ethics

- Political Philosophy

- Philosophy of Art

- Logic & Philosophy of Mathematics

- Philosophy of Religion

- Philosophy of Science

- Philosophy of Language

- Interesting Stuff

- Politics and Current Affairs

- Humanities and Social Sciences

- Science and Technology

- Non-English Discussion

- German Discussion

- Spanish Discussion

- Learning Centre

- Resources

- Books and Papers

- Reading groups

- Questions

- Guest Speakers

- David Pearce

- Massimo Pigliucci

- Debates

- Debate Proposals

- Debate Discussion

- Feedback

- Article submissions

- About TPF

- Help

More Discussions

- Other sites we like

- Social media

- Terms of Service

- Sign In

- Created with PlushForums

- © 2026 The Philosophy Forum