-

praxis

7.1k

praxis

7.1k

To put it as succinctly as I can, the problem I'm having is that being is based in duality and Parmenides's One is supposed to represent the non-dual. We can't say anything about this 'one'. We can't say it's being or non-being. Anything we could say about it is "opinion," or relative. -

Mariner

374The language we use is indeed based in duality, but it can be used to point at non-dual "being". (In fact, we both just did precisely that). This is why theology (theos-logos, the discourse about the gods) must, of necessity, use symbolism and myth (as Plato pointed out), rather than direct speech.

Mariner

374The language we use is indeed based in duality, but it can be used to point at non-dual "being". (In fact, we both just did precisely that). This is why theology (theos-logos, the discourse about the gods) must, of necessity, use symbolism and myth (as Plato pointed out), rather than direct speech. -

praxis

7.1k

praxis

7.1k

I didn't point to non-dual being. I pointed to non-duality. Being is relative to not being and a duality.

If one thing exists then nothing can be said about that thing. You can't even say 'one' or 'thing', right? Attributing any qualities to it is pure fiction. -

Mariner

374I didn't point to non-dual being. I pointed to non-duality. Being is relative to not being and a duality. — praxis

Mariner

374I didn't point to non-dual being. I pointed to non-duality. Being is relative to not being and a duality. — praxis

You speak of non-duality, I put "being" in quotation marks to indicate that I was not talking about being (or, dual being).

Your following comments are apophatic in nature (and I agree with them taken in that context). -

Mariner

374how do you distinguish the being of numbers and napolean as nonexistent from the being of existing beings? What makes a being exist? — Blue Lux

Mariner

374how do you distinguish the being of numbers and napolean as nonexistent from the being of existing beings? What makes a being exist? — Blue Lux

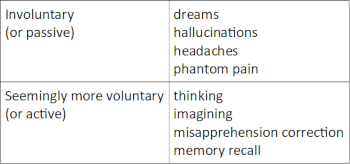

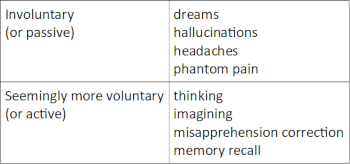

We have a non-sensorial property that allows us to distinguish between dream and non-dream, between hallucination and non-hallucination. (Even if there are borderline cases, perhaps drug-induced, the principle is sound and the property serves us in the vast, vast majority of cases).

The same property is at work in distinguishing between existence and non-existence of beings.

If I had to give a name to this property, I would call it "awareness". And the thing that it is aware of is "presence".

There are types of beings?

Sure, just as there are dreams and non-dreams, etc.

What makes something exist?

Here we go into the terrain of cosmological arguments. What makes something exist is always some pre-existing thing. (This is analogous, but not identical, to Aristotle's argument about act, potency, and the prime mover; but this argument is nothing but a roundabout way to provide an unnecessary justification to the property of awareness).

Are there types of existences?

Is the not a whole, universal here?

Why would these two sentences not be complementary rather than opposed? The universe (taken as the Parmenidean Being) can be one and whole, and still there can be types of existences within it. -

Blue Lux

581We have a non-sensorial property that allows us to distinguish between dream and non-dream, between hallucination and non-hallucination. — Mariner

Blue Lux

581We have a non-sensorial property that allows us to distinguish between dream and non-dream, between hallucination and non-hallucination. — Mariner

Husserl would disagree with you.

The intentional content of a hallucination or dream is absolutely indistinguishable in its being from the intentional content of any experience, which would be the content of the 'object' of an intentionality--which is what Husserl explains with terms like noema, noesis and hyle (originally Aristotelian).

Consciousness is always consciousness of something, and this something it is conscious of always has a mode of being which is absolutely indistinguishable, in the proximal sense, relating to consciousness and the phenomenological paradigm of human experience. -

S

11.7kI don’t know if you really responded to S in that, as far as I can tell so far, there’s no meaningful difference between a “transcendent Deity” and, say, the Eastern concept of emptiness. An atheist can believe in emptiness. — praxis

S

11.7kI don’t know if you really responded to S in that, as far as I can tell so far, there’s no meaningful difference between a “transcendent Deity” and, say, the Eastern concept of emptiness. An atheist can believe in emptiness. — praxis

That was my reaction also - that it doesn't really get to what I was talking about. His reply contains a lot of words, but what are they really saying, and why? Are they basically just saying "Be more sceptical", but then my response would of course be "Why?". -

S

11.7kWhat you - not just you - are loosing sight of here is the understanding that there are things, the very knowledge of which are transformative. Meaning that, ‘worldly beings’ [that includes just about everyone] actually don’t know what is real at all, due to inherent un-wisdom. So the point of spiritual discipline is to ‘see things as they truly are’. And this is even preserved in scientific method, with the caveat that modern science is generally limited to what is quantifiable. Whereas, in the traditions of sapiential philosophy, you will encounter an approach which encompasses the domain of quality.

S

11.7kWhat you - not just you - are loosing sight of here is the understanding that there are things, the very knowledge of which are transformative. Meaning that, ‘worldly beings’ [that includes just about everyone] actually don’t know what is real at all, due to inherent un-wisdom. So the point of spiritual discipline is to ‘see things as they truly are’. And this is even preserved in scientific method, with the caveat that modern science is generally limited to what is quantifiable. Whereas, in the traditions of sapiential philosophy, you will encounter an approach which encompasses the domain of quality.

In any case, in any of the traditional schools of wisdom, there is an understanding that the mind has to clear itself of obstructions and hindrances so as to see the true ‘object of knowledge’. You will find that in Greek, Indian, Chinese and Semitic philosophies. But we have lost sight of that, for complex historical reasons, the main one being the reduction of everything to language and symbolic abstractions. The original discipline was always aimed at ‘meta-noia’ which mean ‘transformation of perception’. And if you understand that, it puts the whole question in a different perspective.

What you - again not just you - are caught up in, is the Enlightenment reaction against ecclesiastical religion. That is obviously a broad historical movement which has had vast consequences that are still all unfolding.

Regarding your question about the meaningful differences - I observed some time back, some debates between two philosophers you might call ‘classical theists’ - namely, Ed Feser [Catholic] and D B Hart [Orthodox] and some of the ID proponents. And both of them were accused of being atheist, or being near to atheist, in some basic way. But it’s precisely because they both understand the real meaning of the transcendent nature of Deity. Whereas, they argue, the ID advocates tend to loose sight of that or to depict ‘being’ as ‘a being’ - a super-engineer, in effect, which is pretty much the kind of God that Dawkins vituperates against. — Wayfarer

That's quite a long reply, which isn't necessarily a good thing. How much of it is on point? How much of it specifically addresses what you quoted of me? How much of it really needed to be said? How much of it requires clarification?

It's too long for me to address in my usual manner of meticulously breaking it down quote-by-quote.

The gist of much of it seems to be that you view me as though I am trapped inside Plato's cave. You think that I don't have sight of this "knowledge" which you say is "transformative", and that I don't know what's real "at all". I'm not of a "spiritual" mindset, and don't "see things as they truly are".

Well, my reaction to that is that that is just your perspective, and I would rather tackle the details behind these broad and unspecific statements of yours. What knowledge? Is it really knowledge? Transformative in what way? Is that good or bad? What don't you think I know is real? And, importantly, can you actually back any of this up?

As for the last paragraph, which is more on point, though still vague, you say that you've seen a video in which there are a couple of guys who "understand the real meaning of the transcendent nature of Deity". If you're able to "recognise" that, then does that mean that you also think that you understand the real meaning of the transcendent nature of Deity? If so, I have one simple request. Please answer the following questions. What is this meaning? What is the transcendent nature of Deity? How have you come upon this knowledge? Why is this meaning "the real" meaning?

You suggest that the ID advocates get it wrong by depicting "being" as "a being". But that's not what I have done. I associate "being" with existence, only it seems that "being" is a word that certain people use who treat it as something special, but seem to have difficulty explaining it or an unwillingness to do so. I associate "a being" with an entity, but again, it seems that certain people don't accept that with regards to God, because they treat God as special. But, of course, just because you might want to set some notion apart as special, that doesn't mean that it's right or true or reasonable or justified or that it makes any sense to do so. That's something that can be investigated, but it can't be if we don't go into the necessary details and get stuck at the tip of the iceberg. -

S

11.7kIt can be argued that both faith and reason can lead to the same place if followed far enough. Perhaps what creates the supposedly huge gap between theism and atheism is that most of us only follow our chosen path a short way down the trail, and then we stop, and build a fort. — Jake

S

11.7kIt can be argued that both faith and reason can lead to the same place if followed far enough. Perhaps what creates the supposedly huge gap between theism and atheism is that most of us only follow our chosen path a short way down the trail, and then we stop, and build a fort. — Jake

Yes, that can be argued, but that doesn't seem to address my point. By a meaningful difference, I simply meant that the two positions should be mutually exclusive. That is, I shouldn't be able to be both an atheist and a theist in the same sense. That's a precursor to a meaningful discussion, in my assessment. Do you agree? -

Jake

1.4kYes, that can be argued, but that doesn't seem to address my point. — S

Jake

1.4kYes, that can be argued, but that doesn't seem to address my point. — S

Apologies, but I've forgotten what your point is in this particular case.

By a meaningful difference, I simply meant that the two positions should be mutually exclusive. — S

In the real world, or in the dictionary? As example...

In the dictionary, things exist or not, yes or no. The dictionary is created by humans, and humans are made of thought, a highly dualistic electro-chemical information medium which operates by a process of conceptual division. The dictionary attempts to impose this human generated dualistic conceptual system upon reality.

In the real world, the largest part of reality by far, space, can not be firmly said to either exist or not exist. Our dualistic minds demand that we file space in to one category or another, but reality is not required to comply with our limitations. Space is not required to either exist or not exist, one or the other, just because that's how we like to look at things.

That is, I shouldn't be able to be both an atheist and a theist in the same sense. — S

It's the same with theism/atheism, faith/reason. You declare yourself to be an atheist, and your atheism is built upon faith. You are against faith, and for faith, both at the same time. You are against reason, and for reason, both at the same time. It's not all neat and tidy, black and white, like you want it to be.

But of course, you've totally missed the larger point I was attempting to make. Faith and reason can lead to the same place if followed far enough. -

Rank Amateur

1.5kFort Agnostic, featuring high walls, a lovely moat, and a tall tower upon which to look down on the ignorant masses — praxis

Rank Amateur

1.5kFort Agnostic, featuring high walls, a lovely moat, and a tall tower upon which to look down on the ignorant masses — praxis

you forgot to add " and fart in their general direction " -

Mariner

374Husserl would disagree with you. — Blue Lux

Mariner

374Husserl would disagree with you. — Blue Lux

Perhaps he would, but not on the strength of what followed in your post, which basically reinforced my point. (Incidentally, Husserl is part of what informed my views about this).

If "the intentional content of a hallucination or dream is absolutely indistinguishable in its being from the intentional content of any experience", but we distinguish ordinary experience from hallucinations and dreams without any difficulty, there must be something not derived from the intentional content which allows us to do it. This is what I called "presence". But the name is just a label and does little more than to give us a handy tool to refer to it. What matters is that we can distinguish them, and this requires some distinction between the objects of consciousness (which, as Husserl said, is not derived from their intentional content), as well as some property in the subject of experience that is attuned to this distinction. -

jorndoe

4.2kWe have a non-sensorial property that allows us to distinguish between dream and non-dream, between hallucination and non-hallucination. — Mariner

jorndoe

4.2kWe have a non-sensorial property that allows us to distinguish between dream and non-dream, between hallucination and non-hallucination. — Mariner

Well, I can generally differentiate dream and awake when I wake up (☕ time).

I don't hallucinate often (I think) :) in some cases I can probably reason it out; in general, not so sure.

Anyway, I'd just call them more phenomenological (mind, self, occurrences).

Could perhaps be contrasted by extra-selves (empirical, perception involves phenomenologicals).

And maybe abstracts (numbers, Platonia, inert, lifeless, ideals).

Where dreams and hallucinations are imaginary/fictional, I guess non-dream and non-hallucination are intended to be real (in this context)?

The "being" versus "existence" thing just seems to add confusion. -

praxis

7.1k... humans are made of thought, a highly dualistic electro-chemical information medium which operates by a process of conceptual division. — Jake

praxis

7.1k... humans are made of thought, a highly dualistic electro-chemical information medium which operates by a process of conceptual division. — Jake

What is it that makes an electro-chemical information medium dualistic? Is, for example, a mechanical recycling device that separates bottles from cans dualistic? If not, is that because the machine doesn’t have ‘thoughts’? What if the machine were computerized, utilizing an information medium. Would it then be dualistic? -

Limitless Science

17Doesn't Atheism just mean: "I don't believe, I want proof!"? I'd recommend to move to a different word like just: "the non believers". I'm not an Atheist. I'm just a no believer! Why doesn't we change our expression? Why say I'm an Atheist over I'm not a believer?

Limitless Science

17Doesn't Atheism just mean: "I don't believe, I want proof!"? I'd recommend to move to a different word like just: "the non believers". I'm not an Atheist. I'm just a no believer! Why doesn't we change our expression? Why say I'm an Atheist over I'm not a believer?

Because yes, people have asked me what is an Atheist! Why speak in riddles like Gandalf? :cry: -

Jake

1.4kWhat is it that makes an electro-chemical information medium dualistic? Is, for example, a mechanical recycling device that separates bottles from cans dualistic? — praxis

Jake

1.4kWhat is it that makes an electro-chemical information medium dualistic? Is, for example, a mechanical recycling device that separates bottles from cans dualistic? — praxis

I'm referring to human thought, which is an electro-chemical information medium, that operates by a process of division. Don't believe me, see it for yourself, observe your own mind.

Consider the experience "I am thinking XYZ". You experience the thinker as being separate, divided from, the content of thought. Within your own mind you experience 1) the observer and 2) the observed. That's the dualistic operation of thought dividing you from yourself.

I don't know anything about mechanical recycling devices, sorry. -

Wayfarer

26.2kThe gist of much of it seems to be that you view me as though I am trapped inside Plato's cave. You think that I don't have sight of this "knowledge" which you say is "transformative", and that I don't know what's real "at all". I'm not of a "spiritual" mindset, and don't "see things as they truly are". — S

Wayfarer

26.2kThe gist of much of it seems to be that you view me as though I am trapped inside Plato's cave. You think that I don't have sight of this "knowledge" which you say is "transformative", and that I don't know what's real "at all". I'm not of a "spiritual" mindset, and don't "see things as they truly are". — S

That's a pretty accurate paraphrase but as I said, this is not peculiar to you. As the original analogy suggests, it is the common lot of mankind (myself included, although I am at least prepared to acknowledge it.)

As for the last paragraph, which is more on point, though still vague, you say that you've seen a video in which there are a couple of guys who "understand the real meaning of the transcendent nature of Deity". If you're able to "recognise" that, then does that mean that you also think that you understand the real meaning of the transcendent nature of Deity? If so, I have one simple request. Please answer the following questions. What is this meaning? What is the transcendent nature of Deity? How have you come upon this knowledge? Why is this meaning "the real" meaning? — S

The 'couple of guys' are academics with many books to their credit on these topics. I cite them because they're educated in classical theology - Catholic and Orthodox, respectively, which, I think, is superior to much of the 'pop theology' of current evangelical Christianity.

The point I'm labouring to make, is that the claim that there is no evidence for 'belief in God' rests on a misunderstanding of what kind of belief it is. In science, you have an equation or hypothesis on the left hand side, which makes a prediction about something specific, on the right hand side. You test your hypothesis against the results or observations. Science works by excluding everything which is not germane to that particular theory, even if the theory is very broad in application. Many of the atheist criticisms of religious belief implicitly assume that they serve the same kind of purpose - but they don't. Religion doesn't attempt to do that; it is about, let's see, establishing a relationship with the foundational principle of the universe (to express it in the philosophical lexicon.) So it is irremediably first-person in some important sense, as distinct from the third-person, arms-length procedures of science.

As has been pointed out, a lot of this confusion rests on the way that science developed out of 'natural philosophy' in the 17-18th Century. It was commonplace for Newton, Galileo, and the like, to assume that the natural laws were 'God's handiwork'. However the problem with that attitude is that it is a two-edged sword - as more became known about the physical universe, the apparent need of a 'God of the gaps' correspondingly diminished (until He became 'a ghost in his own machine', as one writer put it). But it's positing God as a link in the chain of scientific reasoning that is the problem from the outset.

I associate "a being" with an entity, but again, it seems that certain people don't accept that with regards to God, because they treat God as special. But, of course, just because you might want to set some notion apart as special, that doesn't mean that it's right or true or reasonable or justified or that it makes any sense to do so. — S

It's because in philosophy of religion, what is referred to as deity or first principle or God is differentiated from the 'domain of phenomena' as a matter of ontology. Now, as ontology (and metaphysics) has generally fallen out of favour, the distinction itself has become generally unintelligible; there is no conceptual space in modern discourse which accommodates such distinctions.

I do appreciate that you are taking the argument seriously, and trying to fathom why 'being' could be different from 'beings', and that it is a difficult idea. Perhaps this blog post by Bill Vallicella will help cast some light. And also this review of a book by 'one of those guys' that sets out explain why atheist criticisms of God frequently miss the mark. -

praxis

7.1k

praxis

7.1k

The point is that you’re apparently confusing thought or information processing with dualism or something that ‘operates by a process of division’. We’re not continuously self-conscious, nor is self-consciousness necessary for information processing.

Dualism is only an issue because of our self concept, or rather, our attachment to the concept. -

Jake

1.4kThe point is that you’re apparently confusing thought or information processing with dualism or something that ‘operates by a process of division’. We’re not continuously self-conscious, nor is self-consciousness necessary for information processing.Dualism is only an issue because of our self concept, or rather, our attachment to the concept. — praxis

Jake

1.4kThe point is that you’re apparently confusing thought or information processing with dualism or something that ‘operates by a process of division’. We’re not continuously self-conscious, nor is self-consciousness necessary for information processing.Dualism is only an issue because of our self concept, or rather, our attachment to the concept. — praxis

Consider the noun. It's purpose is to conceptually divide one part of reality from another. -

praxis

7.1kGod is a not a being among beings, but the very Being of beings. To deny God, then, is not like denying an orbiting teapot; it is more like denying Being itself. Or it is more like denying truth itself as opposed to denying that a particular proposition is true.

praxis

7.1kGod is a not a being among beings, but the very Being of beings. To deny God, then, is not like denying an orbiting teapot; it is more like denying Being itself. Or it is more like denying truth itself as opposed to denying that a particular proposition is true.

And the widely-bruited 'death of God?' It is an 'event' of rather more significance than the discovery that there is no celestial teapot (or Santa Claus, or . . . ) after all. — Bill Vallicella [from Wayfarer's link]

Imagine the above as a timeless, uniform, unchanging, undivided, ungenerated, indestructible whole and the only thing that exists: The Parmenidean One. Attributing any qualities to it can only be considered fiction. It cannot be considered God because God exists in relation to something else (most relevantly us). If God exists in relation to us then there must be a larger whole that we share.

The impetus to fill this conceptual space with God is understandable, it being the ultimate, and therefore the last refuge for ultimate authority. Can we deny "truth itself"? Yeah, we can.

God didn't die in the Enlightenment, he's alive and well. Ultimate authority died. -

Mariner

374No disagreement there. Meaningfulness does not run across these lines. And notice that drug-induced experiences were singled out in my first comment about this subject. The point here is that the dinstiction between existent and non-existent is very, very, very often a clear one. Even prophetic experiences (which are, by definition, the epitome of meaningfulness) are not confused by the subject with ordinary ones.

Mariner

374No disagreement there. Meaningfulness does not run across these lines. And notice that drug-induced experiences were singled out in my first comment about this subject. The point here is that the dinstiction between existent and non-existent is very, very, very often a clear one. Even prophetic experiences (which are, by definition, the epitome of meaningfulness) are not confused by the subject with ordinary ones. -

Blue Lux

581How is the hallucination something nonexistent, especially when 'its' noema is existent?

Blue Lux

581How is the hallucination something nonexistent, especially when 'its' noema is existent?

An eidetic reduction in place to determine the whether or not veridical nature of a noema seems to be inconsequential. This is the case for a few reasons, namely that questioning the veridicality of a noema is to establish a disconnect between reality and the immediacy of consciousness, and secondly it is to presuppose what reality is and consequently how a veridical noema is anything more than a superfluous demonstration. If there is a noema, manifest in hyle, there is a veridicality: this is obvious, no? And so what makes the experience of something not real? What makes, perhaps, a phenomenal object different than a perceptual, tangible object, that is, in terms of its existence? And, I guess the bigger question is, is a thought existent? Does an abstract or phenomenal object exist? Is there a being of such an object? -

Mariner

374I think you are overthinking this. The issue is not meaningfulness or veridicality. The issue is whatever it is that we use to distinguish between hallucination and non-hallucination. Call it "X" if you prefer. The simple fact is that we don't have ordinary problems in making this distinction. Even borderline cases (e.g. phantom limbs) can be distinguished by all involved (including the subject of the hallucination), rather easily in practice.

Mariner

374I think you are overthinking this. The issue is not meaningfulness or veridicality. The issue is whatever it is that we use to distinguish between hallucination and non-hallucination. Call it "X" if you prefer. The simple fact is that we don't have ordinary problems in making this distinction. Even borderline cases (e.g. phantom limbs) can be distinguished by all involved (including the subject of the hallucination), rather easily in practice.

...what makes the experience of something not real? — Blue Lux

Nothing. The issue is not one of "real x not-real" either. Experiences are real, period. (Else they are not experiences at all). The referent of an experience may be real or not -- we can think about our mother or about Frodo Baggins. The experience of thinking will be real, but the referent of the thinking will be fictional in one case, factual in the other.

And, I guess the bigger question is, is a thought existent? Does an abstract or phenomenal object exist? Is there a being of such an object? — Blue Lux

Well, our thoughts are (all of them) existent. But the thought of, say, Sherlock Holmes is fictional (since he is fictional). We can recreate Holmes' thoughts in our own mind by reading a book, but it will be our recreation of a (fictional) thought, it will not be "Holmes' thoughts". We can discuss what is the kind of existence that thoughts have. It need not be a binary, black-and-white property. Thoughts have existence in a different mode than rocks; they exist more as processes than as static entities. But processes exist in a bona fide manner, although dynamically rather than statically. (Of course, a rock is merely a slow process, slow enough for us to treat it statically; but this is not the core of our discussion)

An abstract object, pretty much by the definition of "abstract" (which means, "extracted from"), does not exist. It was abstracted from something which did exist, but it did not exist before some mind abstracted it (or it would not have been necessary to abstract it in the first place). The universal property that was extracted from a series of observations does not exist, even though each instance exists. So, dogs exist, but dogness does not. We cannot distinguish between imaginary and non-imaginary (or, hallucinatory, or, dream) dogness. But we can distinguish between imaginary and non-imaginary dogs.

However, there is something which is common to dogs which we use to identify them; in other words, there is dogness, even though it does not exist. This, in a nutshell, is the distinction between being and existence. There is a being of dogness, but there is no existence of dogness. And the criteria for defining whether X has "being but not existence" or "being and existence" -- there cannot be something which has existence but not being, since existence is a subset of being -- is the imagination/hallucination test. What this test identifies is the possibility of presence, which is, as indicated earlier, the "perception of existence" that we humans deal with in our everyday lives. (This becomes more and more circular as we dive into thinking about it rather than experiencing it first-hand, and no wonder. Thought is not the dominant property here, and to think otherwise is a path that leads us nowhere).

Welcome to The Philosophy Forum!

Get involved in philosophical discussions about knowledge, truth, language, consciousness, science, politics, religion, logic and mathematics, art, history, and lots more. No ads, no clutter, and very little agreement — just fascinating conversations.

Categories

- Guest category

- Phil. Writing Challenge - June 2025

- The Lounge

- General Philosophy

- Metaphysics & Epistemology

- Philosophy of Mind

- Ethics

- Political Philosophy

- Philosophy of Art

- Logic & Philosophy of Mathematics

- Philosophy of Religion

- Philosophy of Science

- Philosophy of Language

- Interesting Stuff

- Politics and Current Affairs

- Humanities and Social Sciences

- Science and Technology

- Non-English Discussion

- German Discussion

- Spanish Discussion

- Learning Centre

- Resources

- Books and Papers

- Reading groups

- Questions

- Guest Speakers

- David Pearce

- Massimo Pigliucci

- Debates

- Debate Proposals

- Debate Discussion

- Feedback

- Article submissions

- About TPF

- Help

More Discussions

- Other sites we like

- Social media

- Terms of Service

- Sign In

- Created with PlushForums

- © 2026 The Philosophy Forum