-

Rich

3.2kTherefore it is logically impossible that an object, and its parts coexist, at the same time, as objects. — Metaphysician Undercover

Rich

3.2kTherefore it is logically impossible that an object, and its parts coexist, at the same time, as objects. — Metaphysician Undercover

This is as far from an issue of logic as it comes. It is a matter of whether one can conceive of a unity of forms which in themselves contain forms. The answer is obviously yes. We have waves within an ocean, mountains arising from the beach, a sky arising from the mountains, etc. It is all a unity as is our body yet we can still perceive forms within these forms.

How does the mind create all if this. Just try doing contour drawing where forms are created by continuous waving lines without ever picking the pen off a sheet of paper. The critical concept is that there is no emptiness anywhere in the universe. Everything is connected. Duality sinks into unity as does everything else. However. unity does have fundamental characteristics or else it could not get things rolling along. -

Metaphysician Undercover

14.8kThis is as far from an issue of logic as it comes. It is a matter of whether one can conceive of a unity of forms which in themselves contain forms. The answer is obviously yes. We have waves within an ocean, mountains arising from the beach, a sky arising from the mountains, etc. It is all a unity as is our body yet we can still perceive forms within these forms. — Rich

Metaphysician Undercover

14.8kThis is as far from an issue of logic as it comes. It is a matter of whether one can conceive of a unity of forms which in themselves contain forms. The answer is obviously yes. We have waves within an ocean, mountains arising from the beach, a sky arising from the mountains, etc. It is all a unity as is our body yet we can still perceive forms within these forms. — Rich

I'm not talking about forms, I'm talking about objects. A form cannot be said to be an object unless it has substantial existence. Take your waves and ocean for example. We'd commonly say that the ocean has substantial existence, and the waves are a property of the ocean. The ocean is the logical subject, and the waves are the predicate. So long as the ocean is the object of your attention (the logical subject), the waves will always be the property of the ocean and not objects themselves. If you shift your attention to the wave, then it becomes the object of your attention (the logical subject) and the ocean is no longer the object of your attention. You predicate properties of the waves. If you insist that your object (logical subject) is both the ocean and the waves, the you have contradiction. -

Rich

3.2kwaves will always be the property of the ocean and not objects themselves — Metaphysician Undercover

Rich

3.2kwaves will always be the property of the ocean and not objects themselves — Metaphysician Undercover

Only because that is the way you view it. I see them all as objects as real forms.

You predicate properties of the waves. If you insist that your object (logical subject) is both the ocean and the waves, the you have contradiction. — Metaphysician Undercover

No, just a different way of viewing things. A good example is this:

Here is how a single unitary line creates forms:

https://www.pinterest.com/pin/535295105679649688/ -

Metaphysician Undercover

14.8kOnly because that is the way you view it. I see them all as objects as real forms. — Rich

Metaphysician Undercover

14.8kOnly because that is the way you view it. I see them all as objects as real forms. — Rich

Because I view it logically, and you view it illogically?

No, just a different way of viewing things. A good example is this: — Rich

That's an adequate example. It's either a duck or a rabbit. To say that it's a duck and a rabbit is contradictory, illogical. We can take one as the object, or the other, but there is incompatibility which prevents us from saying that the two things coexist as the object. It's not two objects, its one.

And that's the point with wayfarer's statementthings that exist on one level, do not exist on another. — Wayfarer

We could say that on one level it's a duck, and on another level it's a rabbit, but we cannot say that on the same level it is a rabbit and a duck, because that is to make one object into two objects, and that's contradictory.

All the numbers are like that. Consider the numeral "4". On one level, this signifies four distinct units. But on another level, it signifies one unit, the number four which is a unified group, as a unit. It cannot signify four distinct unities, and one unity, at the same time, because this would be contradictory. -

Rich

3.2kBecause I view it logically, and you view it illogically? — Metaphysician Undercover

Rich

3.2kBecause I view it logically, and you view it illogically? — Metaphysician Undercover

Your logic has become an obstruction that limits you. I don't have such an obstruction. I'm only interested in understanding by whatever means available.

It's either a duck or a rabbit. — Metaphysician Undercover

It's actually both at the same time and the same place.

We could say that on one level it's a duck, and on another level it's a rabbit, but we cannot say that on the same level it is a rabbit and a duck, because that is to make one object into two objects, and that's contradictory. — Metaphysician Undercover

Clearly they are both at the same level. What changes is the perception of mind as it superimposes the form on memory.

The Pinterest continuous line drawing in my post's link illustrates how a never-ending number of forms are created out of unity. -

Metaphysician Undercover

14.8k

Metaphysician Undercover

14.8k

There's a reason why we make rules of logic, and adhere to them. That's so we don't get confused by simple issues, as you have.

Your logic has become an obstruction that limits you. I don't have such an obstruction. I'm only interested in understanding by whatever means available. — Rich

I find it extremely doubtful that throwing away the fundamental rules of logic because they don't support what you happen to believe, is conducive to understanding. -

Rich

3.2kThere's a reason why we make rules of logic, and adhere to them. That's so we don't get confused by simple issues, as you have. — Metaphysician Undercover

Rich

3.2kThere's a reason why we make rules of logic, and adhere to them. That's so we don't get confused by simple issues, as you have. — Metaphysician Undercover

Rules of logic were designed so someone can rule. I feel no such constraint. I use every faculty and tool available to me.

I find it extremely doubtful that throwing away the fundamental rules of logic because they don't support what you happen to believe, is conducive to understanding. — Metaphysician Undercover

Sometimes it is time to move on. -

Wayfarer

26.1kIf we give to "existence" its etymological meaning, then what "exists" is "what" arises or what is "created". Whereas "reality" is a much more general concepts, for example even "dreams" are a "reality", in some sense. The "Absolute" of many philosophies instead simply "is", since it does not "arise". The same in some sense can be said to "truths" IMO, like mathematical ones (albeit there is also an element of contingency in mathematics: the language used etc). — boundless

Wayfarer

26.1kIf we give to "existence" its etymological meaning, then what "exists" is "what" arises or what is "created". Whereas "reality" is a much more general concepts, for example even "dreams" are a "reality", in some sense. The "Absolute" of many philosophies instead simply "is", since it does not "arise". The same in some sense can be said to "truths" IMO, like mathematical ones (albeit there is also an element of contingency in mathematics: the language used etc). — boundless

That is an insightful comment. What you’re touching on here is the relationship between ‘the uncreated’ and the phenomenal domain - the domain of sensory experience. Nowadays any mention of ‘the uncreated’ is categorised as a religious idea - which I suppose it is in some ways. But in the Western philosophical tradition the main source of philosophy about ‘the uncreated’ is the neoPlatonic tradition (as Metaphysician Undiscovered mentioned). And according to the Catholic Encyclopaedia, such philosophers are still categorised as ‘pagan’.

Overall, ‘the uncreated’ is a very difficult idea to grasp. Originally, the intuition was that ‘the uncreated, unconditioned, unborn’ was understood as ‘the source of Being’. In the early days of Christian theology such ideas, originally from the Greek philosophical tradition, were assimilated into Biblical prophecy, although the combination has always been characterised by some tension; the wisdom of Jesus being described as ‘folly to the Greeks’. Nevertheless Greek-speaking Christianity thoroughly absorbed the neo-Platonic philosophy. The Greek reverence for rationality and mathematical reasoning was based on the intuition that mathematical reasoning was inherently more reliable than the testimony of the senses, because the objects of dianoia we’re inherently knowable and constant in a way that sense-objects were not. So they were nearer to the uncreated, in that they likewise weren’t as subject to change and decay as were sense-objects. They were lower than the Ideas, but higher than knowledge concerning particulars.

I was trying to explain above, originally the intuitions of mathematics and rationalism were regarded in ancient philosophy as morally edifying, not simply for their instrumental value or technical power. But it was the association of mathematical and rational insight with mystical insight, typical of the Pythagoreanism, that differentiated Greek from Indian philosophy and was one of the major sources of the Western tradition of natural science. However, science has now basically abandoned the notion of the ‘uncreated’, perhaps because of its religious connotations. -

Pseudonym

1.2kIt is quite usual to believe, nowadays, that 'science knows' or 'science proves' many things that science neither knows nor proves. I am engaged in trying to draw that out, and will continue to do so. — Wayfarer

Pseudonym

1.2kIt is quite usual to believe, nowadays, that 'science knows' or 'science proves' many things that science neither knows nor proves. I am engaged in trying to draw that out, and will continue to do so. — Wayfarer

What is it exactly that people believe science 'knows' or 'proves' that it doesn't? Who are these people and what evidence do you have that they believe this?

If you want to argue that modern science is deeply flawed I'm all with you, our system of funding and publication is appallingly biased and allows some shockingly inaccurate theories to appear valid.

But if you want to argue that most people believe science as a method claims to be able to prove things that it actually cannot, then you'll need to provide some evidence, because I can't think of a single example from the published philosophical literature.

If you want to go further and suggest you have a better method to prove (or even argue meaningfully about) these things that science cannot, then you'll have to do a lot better in demonstrating how you arrived at that conclusion because its far from obvious as you have laid it out so far. -

Wayfarer

26.1kBut if you want to argue that most people believe science as a method claims to be able to prove things that it actually cannot, then you'll need to provide some evidence, because I can't think of a single example from the published philosophical literature. — Pseudonym

Wayfarer

26.1kBut if you want to argue that most people believe science as a method claims to be able to prove things that it actually cannot, then you'll need to provide some evidence, because I can't think of a single example from the published philosophical literature. — Pseudonym

The philosophical issue I see is not to do with scientific method so much as with ‘the scientific worldview’. I would never disparage scientific method when applied to the countless things for which it’s useful. The problem I have is more like science as the arbiter of what ought to be considered meaningful and important. And that naturally issues from the role that science occupies in modern culture, in the sense that it has displaced religion as kind of guide to what the educated person ought to believe. Even then, there are many things I don’t disagree with, or take issue with, except for when it is used to argue against classical philosophical and religious ideas, or to show that such ideas really can be better understood in terms of evolutionary or cognitive science - what is generally called ‘scientific reductionism’.

One of the frequent imputations of the scientific attitude is taken to be that the world is fundamentally meaningless, the product of interactions which can be ultimately understood in terms of physics, and that life itself is essentially a kind of accidental by-product of an essentially meaningless process (which is brilliantly articulated in Bertrand Russell’s classic essay A Free Man’s Worship.) This is not an academic argument - I’ve been posting on forums for ten years and there’s a regular stream of contributors who ask existential questions which are often rationalised in terms of evolutionary psychology, or what I calll ‘Darwinian rationalism’. And they’re often quite despairing, or even pleading, for some reason that life might be considered meaningful.

So, in respect of this thread, the question of whether there is a meaningful distinction between what is real and what exists, is not a scientific question but a philosophical one. And while I certainly agree with you that scientists generally take maths very seriously and understand how powerful it is, the question of the ontological status of number - of what number actually is - is also not a scientific question. (Actually the Wikipedia entry on ‘philosophy of mathematics’ is quite good. One thing that is clear from it, is the enormous range of views on the question.) -

Pseudonym

1.2kThe problem I have is more like science as the arbiter of what ought to be considered meaningful and important. — Wayfarer

Pseudonym

1.2kThe problem I have is more like science as the arbiter of what ought to be considered meaningful and important. — Wayfarer

This is where I think you're going wrong. I don't think anyone is seriously claiming that science is the arbiter of what is meaningful and important. What those who espouse a scientific worldview are saying is that the scientific method is the only way of claiming any objective knowledge about what is meaningful or important. This is very important distinction.

If you feel like there's a god, for example, then no one of a scientific worldview is seriously claiming that you may not have that belief, but if you claim, in the public domain, that there is a God, based on the fact that you think there is, there are people who will, quite fairly, argue that this is not a useful way to further public knowledge.

The strawman I think you're making is to conflate this view about the practicality of methods for arriving at public knowledge, with assumptions about the axioms that are required by any epistemological approach.

The claim that is being made by the scientific world view is that it is successful, that it makes useful prediction which could not be accounted for by chance. No-one to my knowledge, is claiming that such a system is not founded on axioms that must simply be taken as brute fact. They are claiming that such axioms are useful ones to adhere to because of the empirically proven utility of the system they allow.

We might all be brains in a vat, we might all be figment of my imagination, logic might not be justified, causality might be wrong, but presuming these things to be true has yielded no demonstrably useful epistemology. Assuming they are not has given us physics, sociology, psychology, biology and a whole host of useful information about ourselves and the world.

Of course if the axioms it is all based on turn out to be wrong, the whole thing comes crashing down, but what use is that knowledge if there's nothing more useful to replace it with? -

boundless

740

boundless

740

My view actually is that while we can say that even dreams are real, we have to make some "distinctions" between "the levels of reality". For example there is clearly a distincion between a "table" and an electron. And between an electron and a dream.

Edited because the response was incomplete. Sorry, Rich !

That is an insightful comment. What you’re touching on here is the relationship between ‘the uncreated’ and the phenomenal domain - the domain of sensory experience. Nowadays any mention of ‘the uncreated’ is categorised as a religious idea - which I suppose it is in some ways. But in the Western philosophical tradition the main source of philosophy about ‘the uncreated’ is the neoPlatonic tradition (as Metaphysician Undiscovered mentioned). And according to the Catholic Encyclopaedia, such philosophers are still categorised as ‘pagan’. — Wayfarer

Yeah, actually what we call "Catholicism" comes largely from St Thomas Aquinas. And IMO in Aquinas there are a lot of ideas that come directly from Platonism (both "old" and "neo"). These "pagan" philosophies ironically over the centuries helped to "define" the "orthodoxy".

Overall, ‘the uncreated’ is a very difficult idea to grasp. Originally, the intuition was that ‘the uncreated, unconditioned, unborn’ was understood as ‘the source of Being’. In the early days of Christian theology such ideas, originally from the Greek philosophical tradition, were assimilated into Biblical prophecy, although the combination has always been characterised by some tension; the wisdom of Jesus being described as ‘folly to the Greeks’. Nevertheless Greek-speaking Christianity thoroughly absorbed the neo-Platonic philosophy. The Greek reverence for rationality and mathematical reasoning was based on the intuition that mathematical reasoning was inherently more reliable than the testimony of the senses, because the objects of dianoia we’re inherently knowable and constant in a way that sense-objects were not. So they were nearer to the uncreated, in that they likewise weren’t as subject to change and decay as were sense-objects. They were lower than the Ideas, but higher than knowledge concerning particulars. — Wayfarer

Agreed! At first the "uncreated" was thought in a lot very ancient philosophies (see the "Apeiron" of Anaximander, "Brahman" of the Hindus, the "Dao"...) as the "Source". It was seen as a sort of "ineffably simple", so to speak, ground of being that "is" (rather than ex-ist). Interestingly in the Greek World, especially in Platonic philosophies the idea of "simplicity" reamined and in fact in neo-Platonism "the First" was seen "beyond being", simple etc. At the same time however Plato introduced the idea of a plurality of "uncreated" objects, the Forms. This appealed to those who believed in a "Personal God", since it was very simplet to identify them with the "ideas in the Divine Mind". For example human beings were seen as "particular" of the idea of "Human Being" in God's MInd.

But the relationship between the "pagan" thought and Christian orthodoxy was always a complex one. For example the view that "the pious is loved by the gods beceause he is pious" comes directly from Plato and IMO it is the reason behind the "primacy of conscience" of Catholic theology. At the same time however Catholicism aaccepts the "salvation from grace". Or the view that we can know God by His creation (an idea found already in the Pauline Epistles) but at the same time we cannot really know Him without the Revelation. So there are a lot of "paradoxes" raised by this issue.

I was trying to explain above, originally the intuitions of mathematics and rationalism were regarded in ancient philosophy as morally edifying, not simply for their instrumental value or technical power. But it was the association of mathematical and rational insight with mystical insight, typical of the Pythagoreanism, that differentiated Greek from Indian philosophy and was one of the major sources of the Western tradition of natural science. However, science has now basically abandoned the notion of the ‘uncreated’, perhaps because of its religious connotations. — Wayfarer

Yeah, the Greek emphasis on mathematics and quantitative reasoning is IMO the greatest break between Western and Indian (and Daoist) philosophy, according to which the only "reality" that was important to study was the experiential one (again Buddhism IMO is the most radical form of this type of "view"). At the same time however the notion of "uncreated" seems to be central to most of the major philosophical and religious system both of the East and the West. And also the reason behind the rise of science in the West rather than in the East.

Being myself interested in both "studies" I have a hard time in reconciling the opposing tendencies of the two types of philosophy.

Regarding the "uncreated", in contemporary science this notion is seen as "unnecessary". In fact to the scientific study the "uncreated" has no "quantitative" role. The problem is that to many scientists this means that it is either an "useless" or even a "superstitious" concept. -

Metaphysician Undercover

14.8kThis is where I think you're going wrong. I don't think anyone is seriously claiming that science is the arbiter of what is meaningful and important. What those who espouse a scientific worldview are saying is that the scientific method is the only way of claiming any objective knowledge about what is meaningful or important. This is very important distinction. — Pseudonym

Metaphysician Undercover

14.8kThis is where I think you're going wrong. I don't think anyone is seriously claiming that science is the arbiter of what is meaningful and important. What those who espouse a scientific worldview are saying is that the scientific method is the only way of claiming any objective knowledge about what is meaningful or important. This is very important distinction. — Pseudonym

I think that this is a misrepresentation. Meaningful things, such as God and the supernatural, are asserted by most of those who hold the scientific worldview, to be non-existent. Therefore it is more than just the case that this worldview decides "objective knowledge about what is meaningful or important", it actually decides what "is" meaningful and important, and denies the existence of that which it deems as not meaningful and important. -

Rich

3.2kOf course if the axioms it is all based on turn out to be wrong, the whole thing comes crashing down, but what use is that knowledge if there's nothing more useful to replace it with? — Pseudonym

Rich

3.2kOf course if the axioms it is all based on turn out to be wrong, the whole thing comes crashing down, but what use is that knowledge if there's nothing more useful to replace it with? — Pseudonym

Theoretically it should come crashing down, in practice scientists just make up new universes or make our current universe 95% invisible. What ever happened to the Mind? Now it is neurons located in the brain that do the thinking? Or is it the neurons in the gut? Sometimes it is genes and often it is that ubiquitous Evolution and Laws of physics that forces our actions. Which is it? And what is it that has feelings? Or is it the frequently used scientific phrase Illusion (as opposed to Dark Matter/Energy).

When there is lots at stake, science just fabricates new stories, and like all professions there is a code of silence and anyone who breaks that code is quickly labeled a mystic, eccentric, or aberration if the carefully codified system of acceptable and unacceptable words. -

Thorongil

3.2kI guess to my ear the term "exists" means to be actualised. — apokrisis

Thorongil

3.2kI guess to my ear the term "exists" means to be actualised. — apokrisis

To be actualized from what? You presuppose the existence of what is being actualized here. I think to be actual is to exist in one manner, namely, in reality, whereas to be potential is to exist in another manner, namely, in the mind or nature of a thing. Language, for example, doesn't actually exists in infants, but it exists potentially. No tree actually exists in my backyard, but it potentially exists. The only category of thing that doesn't exist are impossible things, like square circles. Otherwise, things exist potentially or actually.

That would be where we differ in that you take a theist and Platonist route here? — apokrisis

I don't know. Maybe? Why do you think I am? -

Thorongil

3.2kthings that exist on one level, do not exist on another. — Wayfarer

Thorongil

3.2kthings that exist on one level, do not exist on another. — Wayfarer

This way of couching it corresponds to my correction and confirms my suspicion about Moran's description, which was misleading.

That is the subject of Richard Weaver, Michael Allen Gillespie, and also the 'radical orthodoxy' movement, of which there is quite a good review here (starts from the bottom of the page.) — Wayfarer

My point is that the Radical Orthodoxy people, from whom Brad Gregory imbibes, get Scotus totally wrong, especially on the univocity of being. I agree that Ockham was responsible for some deleterious metaphysical turns in the West, which trickled down into culture. But it is wrong to unambiguously link Scotus with him and thereby to all the bad stuff Gregory speaks of, the foremost of which being the Protestant Reformation.

Do you know what this is an image of? It's an early modern painting of Duns Scotus trampling Lucifer and the heads of various Lutheran reformers underfoot. One wonders what Gregory and his ilk would make of it.... -

apokrisis

7.8kTo be actualized from what? You presuppose the existence of what is being actualized here. I think to be actual is to exist in one manner, namely, in reality, whereas to be potential is to exist in another manner, namely, in the mind or nature of a thing. — Thorongil

apokrisis

7.8kTo be actualized from what? You presuppose the existence of what is being actualized here. I think to be actual is to exist in one manner, namely, in reality, whereas to be potential is to exist in another manner, namely, in the mind or nature of a thing. — Thorongil

Well, we could say they exist in different manners or that they are real in different manners. That still leaves us with the issue of how they are both the same in some sense, but also sharply different. It is the metaphysical distinctions we are trying to draw out which matter.

I think it is just less confusing to talk about potential being and actual being. And I would call both real in that they are ontically distinct yet related - nicely opposed in a mutual dialectical fashion. You really need both to make sense of being.

But then to exist seems to relate to actuality - to being that is definite, concrete, part of the here and now. Potentiality is about what does not yet exist right here and now in concrete fashion, but which might exist at some future place and time. To the degree a potential exists in the here and now, it is a vagueness, an indeterminancy, an Apeiron. It is the opposite of the concrete when it comes to existing.

So there are problems in saying that the potential simply does not exist, and that it is thus not real. That is going too far. It leads to a metaphysics where something must come from nothing - the familiar problem of a metaphysics of being.

But a potential whose existence is vague, unmaterialised, unformed, can be the proper opposite of the kind of existence which is concrete and here and now - a substantial existence. A vague potential is effectively a "nothingness" right at this moment. Or better yet, an "everythingness", as no possibilities have yet been concretely eliminated. And so it can be both real - present as unformed and unmaterialised - and yet completely lack the concrete actuality which denotes "existence".

The same way of thinking can apply to that other standard metaphysical distinction - this time between the concrete and the abstract. An advantage of a triadic Peircean metaphysics is of course that it includes this as well.

So universals or generalities can be considered to be real even when they are abstract objects. Or more accurately for a Peircean process metaphysics, when they are mathematical-strength finalities or necessities. They too "exist" - just not in the concrete here and now fashion of the actual. They exist as ultimate or ideal limits on form.

Again, the terminology gets pushed and pulled about by the underlying metaphysical positions being taken. But Aristotle did do a good job at establishing the basic jargon - missing out only the one crucial dichotomy really, that of the vague~crisp.

So a Peircean metaphysics makes a triad of the potential, the actual, and the necessary.

You have actual concrete substantial existence arising in the middle as the emergently definite and individuated in terms of a time and place.

Then there is the vague potential which is unexpressed possibility. And indeed, unsuppressed possibility. Nothing has yet happened to limit it.

Then there is formal necessity waiting to limit it. The possible becomes the actual by becoming substantially formed in terms of latent regularities. Possibility contains everything, but not everything can be actualised as many of those possibilities would conflict and cancel. You can be a circle, or a square, but not a square circle.

So the term "real" would span all three fundamental categories of being. But "exist" would be reserved for what seems obviously the most developed state of being - the concrete actuality of substantial being where a free potential has been most fully constrained or determined. -

foo

45I think there’s a genuine distinction between the terms, and the reason the distinction has been lost is indeed metaphysical. That is why we can only understand things on a horizontal plane, so to speak. — Wayfarer

foo

45I think there’s a genuine distinction between the terms, and the reason the distinction has been lost is indeed metaphysical. That is why we can only understand things on a horizontal plane, so to speak. — Wayfarer

As far as I can tell, you are making a metaphysical point against other metaphysicians. Reading some of your other posts in this thread, it seems to me that your opponent or the target of your complain is not really the scientific worldview but rather a small group of metaphysicians who build their metaphysics around science rather than the philosophical or religious tradition.

As I understand, science doesn't need more than a certain minimum of metaphysics. Similarly, math doesn't need a metaphysical position on numbers. What really matters are the tangible criteria for progress in the discipline. Metaphysical or religious preferences fall on the other side of the public-private split.

I don't see how we "can only understand things on a horizontal plane." It may be that certain scientistic metaphysicians intentionally pursue this project self-consciously with or without a sense of its limitations. But I think you'd have to make a case for this 'we' at large seeing things horizontally.

Consider also that anti-metaphysical positions are possibly motivated by the desire not to be trapped in systems. Metaphysical systems can themselves be read as attempts to flatten experience with 'magic' words.

There’s more to mind than experience - which is after all textbook empiricism. But as Kant showed, the mind makes use of the categories of the understanding, the primary intuitions, and so on, in order to understand. So there’s more to that than just ‘experience’, there’s also intellectual capacity. — Wayfarer

Yes, I know Kant and Hume. But I wasn't using 'experience' in some fancy way that alludes to books that were long ago state of the art. Reading the traditional books liberated me from the authority of traditional books. Allowing for some exceptions, I think the flight from ordinary usage tends to involve a mystification.

I don't want to be a jerk here, but you are telling me above that there is also 'intellectual capacity' in or 'to' the mind. That is to say that you are telling me nothing. The way you interpreted me to mean the word 'experience' suggests to me that (without realizing it perhaps), you can only see other metaphysicians 'out there.' Those who think science is a trustworthy source of objective knowledge must have some metaphysical as opposed to epistemological position. But we don't have to have some position on what things 'ultimately' are.

We need rather a way of separating fact from opinion. This is a matter of life and death for both the individual and the species. We have a tendency to deceive ourselves or be deceived. We have a tendency to exaggerate the importance of our own discoveries and to mistake our opinions for facts. In my view, this is what grounds our need for science. In this context, it makes perfect sense that science would be built around the measurement of public and non-controversial entities.

'Just the facts, mam.' -

apokrisis

7.8kMetaphysical systems can themselves be read as attempts to flatten experience with 'magic' words. — foo

apokrisis

7.8kMetaphysical systems can themselves be read as attempts to flatten experience with 'magic' words. — foo

We have a tendency to exaggerate the importance of our own discoveries and to mistake our opinions for facts. ... In this context, it makes perfect sense that science would be built around the measurement of public and non-controversal entities. — foo

Hah. This level of commonsense is going to kill the thread. Kudos. :) -

Pseudonym

1.2kMeaningful things, such as God and the supernatural, are asserted by most of those who hold the scientific worldview, to be non-existent. — Metaphysician Undercover

Pseudonym

1.2kMeaningful things, such as God and the supernatural, are asserted by most of those who hold the scientific worldview, to be non-existent. — Metaphysician Undercover

Yes, and magic flying unicorns are asserted by the scientific worldview to be non-existent too. That's what the scientific worldview does and one of the reasons why it has been so successful for the last few hundred years.

A theory is developed which is as simple as possible, inventing a few new concepts as it can and which is falsifiable. That theory is tested and whilst it remains unfalsified, it is held to be a currently good approximation to the truth.

The theory that there is no God is a simple theory - it avoids having to create a new concept not already demonstrated to be 'true' (by the standards set out above). Every event, with the exception of the creation of the universe, can currently be explained without God.

The theory that there is no God (in the Abrahamic sense) is falsifiable - the Bible, the Torah and the Koran are all littered with examples of their God making manifest appearances and affecting the world in way which are obviously divine, so the theory that there isn't a God is perfectly falsifiable, any time "I Am Real" appears in the night sky by rearranging the stars, that would pretty soundly falsify the theory.

So it's entirely within the realms of science to posit a theory that there isn't a God (in the Abrahamic sense), and so far as that theory has not been falsified (nothing has happened that can't be explained by some other valid theory we already have), then it is entirely reasonable for scientists to say that God probably doesn't exists, which is all they've ever said.

Even the Arch atheist himself Richard Dawkins only ever said that God "probably" didn't' exist.

it actually decides what "is" meaningful and important, and denies the existence of that which it deems as not meaningful and important. — Metaphysician Undercover

So this is also a misrepresentation. No-one is denying the existence of anything which is outside of a falsifiable theory. The creation of the universe for example is an "all bets are on" scenario. What science does is simply say that we have no way conducting objective knowledge-seeking discourse about things which are entirely subjective. -

Wayfarer

26.1kReading some of your other posts in this thread, it seems to me that your opponent or the target of your complain is not really the scientific worldview but rather a small group of metaphysicians who build their metaphysics around science rather than the philosophical or religious tradition. — foo

Wayfarer

26.1kReading some of your other posts in this thread, it seems to me that your opponent or the target of your complain is not really the scientific worldview but rather a small group of metaphysicians who build their metaphysics around science rather than the philosophical or religious tradition. — foo

Right. That is what I mean by ‘the scientific worldview’. Because science isn’t ‘a worldview’ - it’s a methodology, a way of doing things, and also a body of knowledge, large and ever-growing. But one can pursue science along any number of axes without making any judgements on ‘the nature of the world’. Saying that ‘the nature of the world’ is such that it can only be understood by science, is going beyond scientific method and in effect putting science in the place formerly occupied by religion. And you can’t say that doesn’t happen on a large scale in today’s culture.

Just the facts, mam.' — foo

In the video in the thread on the Einstein-Bergson debate, Jimena Carneles quotes one of her colleagues who says that ‘facts are like ships in bottles - they’re carefully constructed to seem as if no-one was there to build them’.

We need rather a way of separating fact from opinion. — foo

Perfectly true. But how to do this in respect of what is good, or whether there is anything that is truly good - as distinct from useful, or instrumentally powerful - that is NOT simply a matter of doxai or pistis. And science doesn’t offer that, because its sole concern is with ‘the measurable’.

Interesting fact: in Buddhism there is a list - Buddhists love lists - of the four immeasurables. I won’t list them here, but the fact that they have canonical significance is what is germane. Philosophy, as distinct from science, has to accomodate immeasurables, and at least recognise unknowables.

As far as evolutionary biology is concerned, there can only one measure of success, which is propagation. But there’s not point asking ‘why’ - the only ‘why’ is to survive (which seems very Schopenhauerian to me.)

I don't think anyone is seriously claiming that science is the arbiter of what is meaningful and important. — Pseudonym

Many serious people claim it regularly.

the worldview that guides the moral and spiritual values of an educated person today is the worldview given to us by science. — Steve Pinker

In Science is not the Enemy of the Humanities which is a long and much-discussed essay on this very topic.

The theory that there is no God is a simple theory - it avoids having to create a new concept not already demonstrated to be 'true' (by the standards set out above). Every event, with the exception of the creation of the universe, can currently be explained without God. — Pseudonym

Now, the ‘standards set out above’, namely, those of falsifiability and simplicity, pertain specifically to the empirical sciences. That is, you make a prediction, then you observe and/or experiment and test the hypothesis against the results.

But I don’t think any serious theistic philosophy claims that ‘God’ is this kind of ‘hypothesis’ in the first place. IN fact the very reason that Popper devised ‘falsifiability’ was to differentiate the empirical sciences from such things as metaphysics and theology. So to say that falsifiability is an argument against a metaphysical postulate, is to precisely misunderstand the significance of the criterion of falsifiability.

And the claim that God is ‘a concept’ can only be a kind of category mistake. Concepts have considerable range and scope, but they have to have some way of either representing or saying something meaningful about what it is that they are attempting to depict. But the basic nature of Deity, in the classical tradition, is ‘beyond conceptual thought’. So if it is reduced to a concept, what that ‘concept’ likely is, is a set of words used or arguments deployed in situations such as this - which mean nothing, and which have no relationship to what ‘God’ means to anyone who engages with a theistic tradition. So there’s one less god you have to bother about; I can confidently state that the God you don’t believe in truly doesn’t exist.

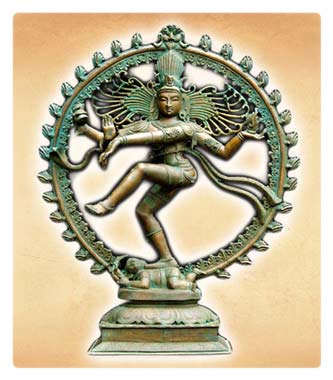

Do you know what this is an image of? — Thorongil

Spot the archetype -

Pseudonym

1.2kMany serious people claim it regularly.

Pseudonym

1.2kMany serious people claim it regularly.

the worldview that guides the moral and spiritual values of an educated person today is the worldview given to us by science. — Steve Pinker — Wayfarer

Not that I wouldn't rather cut my own arm off than agree with anything Steven Pinker says, but he specifically says here that science guides moral and spiritual values, not 'all that there is'. He's claiming that science can provide us with a method of obtaining morals and of determining what have traditionally been called 'spiritual' values. That is a far cry from your claim that it tries to be "the arbiter of what ought to be considered meaningful and important."

Nothing in what Pinker says tells you what you 'ought' to find meaningful or important. You might find opera to be meaningful and important, science makes no judgement on that. You might find that the intricacies of particle physics mean nothing to you and are totally unimportant. The scientific worldview (such as there is one) makes no comment on that.

You're trying to conflate 'meaningful and important' with 'true'. The scientific worldview has a massive amount to say on how we can talk about things being 'true' or likely, and with a huge amount of evidence to support it's right to do so. That's completely different to making claims about what's 'important, or meaningful' in a subjective sense, about which it makes little comment.

The only place science could intervene on what is meaningful is in evolutionary biology, psychology, or neuroscience. For example, It is a good hypothesis that we all evolved by a process of natural selection, it is a good simple hypothesis that all our features are therefore determined by this process, it is a good hypothesis that features which appear to serve no purpose in this regard might be better explained some other way.

Like most mystics, you're trying to subtly make the jump from "science is based on axioms which science itself cannot prove" to "we might as well consult Buddha as Churchland on the problem of conciousness. You cannot make that leap. Churchland 'knows' an vast amount more about conciousness than Buddha did, by any common meaning of the term 'knows'. -

Wayfarer

26.1kThat is a far cry from your claim that it tries to be "the arbiter of what ought to be considered meaningful and important." — Pseudonym

Wayfarer

26.1kThat is a far cry from your claim that it tries to be "the arbiter of what ought to be considered meaningful and important." — Pseudonym

It’s not a ‘ far cry’ - it’s the same thing. The rest of the post builds on this false premise.

You're trying to conflate 'meaningful and important' with 'true'. The scientific worldview has a massive amount to say on how we can talk about things being 'true' or likely, and with a huge amount of evidence to support it's right to do so. That's completely different to making claims about what's 'important, or meaningful' in a subjective sense, about which it makes little comment. — Pseudonym

The point at issue, is the extent to which science does or doesn’t say anything meaningful about questions of quality. So here, you’re basically saying that everything that is not measurable, not quantitative, is subjective. So ‘it’s your business what you believe, but don’t think for a minute it’s scientifically true’.

That is the very point at issue. What I’m concerned with, in this debate, indeed on this forum, is a metaphysic of value - something which can be considered the basis for qualitative judgement, not what is simply measurable or quantifiable. All the bluff and bluster apart, that is what is at issue as far as I’m concerned. -

Pseudonym

1.2kSo here, you’re basically saying that everything that is not measurable, not quantitative, is subjective. So ‘it’s your business what you believe, but don’t think for a minute it’s scientifically true’. — Wayfarer

Pseudonym

1.2kSo here, you’re basically saying that everything that is not measurable, not quantitative, is subjective. So ‘it’s your business what you believe, but don’t think for a minute it’s scientifically true’. — Wayfarer

Yes, that's pretty much the definition of 'objective' and 'subjective'

something which can be considered the basis for qualitative judgement — Wayfarer

There already is something which can be considered the basis for qualitative judgement, it is the sum total of all our biological and cultural influences which lead us to be of a certain opinion about a topic that is entirely subjective. You haven't explained what it is you find unsatisfactory about that such that some other basis is required.

All the bluff and bluster apart, that is what is at issue as far as I’m concerned. — Wayfarer

Your posts read as entirely 'bluff and bluster' you haven't said anything concrete yet on the matter.

The point at issue, is the extent to which science does or doesn’t say anything meaningful about questions of quality. — Wayfarer

This is what I'm sure you'd like the point at issue to be, but science does not have any comment on matters of quality, other than to say that no other approach can say anything meaningful on the matter either. That's what you really take issue with. You're never advocating a Wittgensteinian “Whereof one cannot speak, thereof one must be silent.” approach to metaphysics, but always beneath the surface is the idea, not just that science cannot say anything meaningful about quality, but that theology can.

Science can talk meaningfully about an increasingly wide range of subjects because it can demonstrate the remarkable predictive power of its theories, and thereby show a remarkable justification for it's metaphysical presumptions in terms of utility.

Theology can say nothing meaningful about anything because its purview is entirely subjective. Nothing objectively verified in the world we share supports a theological view. That's not to say that no-one can believe in God, or fairies or solipsism, insofar as they come up with some theory as to how such beliefs fit with the sense-experiences we all share, but it is to say that such theories have no authority, they are qualitative, like artwork, no right, no wrong, just opinion.

Welcome to The Philosophy Forum!

Get involved in philosophical discussions about knowledge, truth, language, consciousness, science, politics, religion, logic and mathematics, art, history, and lots more. No ads, no clutter, and very little agreement — just fascinating conversations.

Categories

- Guest category

- Phil. Writing Challenge - June 2025

- The Lounge

- General Philosophy

- Metaphysics & Epistemology

- Philosophy of Mind

- Ethics

- Political Philosophy

- Philosophy of Art

- Logic & Philosophy of Mathematics

- Philosophy of Religion

- Philosophy of Science

- Philosophy of Language

- Interesting Stuff

- Politics and Current Affairs

- Humanities and Social Sciences

- Science and Technology

- Non-English Discussion

- German Discussion

- Spanish Discussion

- Learning Centre

- Resources

- Books and Papers

- Reading groups

- Questions

- Guest Speakers

- David Pearce

- Massimo Pigliucci

- Debates

- Debate Proposals

- Debate Discussion

- Feedback

- Article submissions

- About TPF

- Help

More Discussions

- Is an ontological fundamental [eg,God] really the greatest mystery in reality? Is reality ineffable?

- Derrida's view on reality and reality and representation relationship

- Relationship between our perception of things and reality (and what is reality anyway?)

- Did the movie SIXTH SENSE destroy the myth that perception is absolute reality?

- Other sites we like

- Social media

- Terms of Service

- Sign In

- Created with PlushForums

- © 2026 The Philosophy Forum