-

Metaphysician Undercover

14.9kNo two things can be in one space, but any one thing can be in two times. — Mww

Metaphysician Undercover

14.9kNo two things can be in one space, but any one thing can be in two times. — Mww

I like your post Mww, but this line stands out to me, as erroneous. Many things seem to share the same space, and that becomes problematic for physics. Consider a solution for example. Then we might assume that each molecule has its own distinct space. But within the molecule there are atoms which share electrons, so the distinct atoms overlap each other in spatial position. And separate electrons share spatial position in a shell. Things get even more difficult with fundamental particles which seem to be all over the place, all the time. So as much as it seems like two things cannot be in the same space at the same time, they really are. And that raises some very interesting questions about the nature of space and substance.

Where it does appear to be controversial is insofar as it calls into question the instinctive sense that the universe simply exists “just so,” wholly independent of — and prior to — any possible apprehension of it. But again, that is a philosophical observation, not an argument against science. It is an argument against drawing philosophical conclusions from naturalistic premises. — Wayfarer

The problem I see with "the universe simply exists 'just so,'” is that the nature of time and free will indicates that there is possibility for real change, at each passing moment. This means that the true "just so" of every moment is decided (selected from possibilities) at that moment. Then we need to conclude that the universe is actually recreated at each moment of passing time, to allow for the reality of deciding the "just so" at each moment.

That is why the passing of time is a very mysterious and misunderstood feature of the universe. And, because so much of the universe appears to be determined from one moment to the next, i.e. mass obeying the law of inertia, the simplistic cop-out, is to opt for determinism, and deny the real possibility for change at each passing moment. This leaves a very simple, linear representation of time, but it is one that is not consistent with human experience. -

Philosophim

3.6kDistance does not disappear if no one measures it — but “distance in meters,” embedded in a metric geometry and operationalized by instruments and conventions, does not exist independently of those frameworks. Likewise with clock time. What exists is change, passage, becoming; what we measure is an abstracted parameter extracted from it. — Wayfarer

Philosophim

3.6kDistance does not disappear if no one measures it — but “distance in meters,” embedded in a metric geometry and operationalized by instruments and conventions, does not exist independently of those frameworks. Likewise with clock time. What exists is change, passage, becoming; what we measure is an abstracted parameter extracted from it. — Wayfarer

Ok, I'm glad we're on the same page there.

The philosophical claim is simply that it does not follow from the existence of something independent to be measured that reality itself can be specified in wholly observer-independent terms. — Wayfarer

I agree with this quantitatively. Its the qualitative aspect that I'm struggling with. We acknowledge that there is something independent we are measuring, but how does the removal of our measuring remove the independent thing we are measuring? It logically can't, because its independent.

Let me imagineThat further move is a metaphysical assumption, not something licensed by the practice of measurement itself. It overlooks the role of the observing mind. — Wayfarer

And this is the part I think you're missing. Its not a metaphysical assumption without basis. The independent existent we are measuring, does not overlook the role of the observing mind. It notes that it is independent of it. Its a metaphysical assumption based on our real, predictable, and objectively confirmed understanding of measuring time. Time as a measurement cannot logically exist if there is not something that would exist independently of our measurement. That's the part I'm trying to get you to look at.

The point is that this quietly undermines the assumption that what is real independently of any observer can serve as the criterion for what truly exists. — Wayfarer

The point is that what truly exists is independent of any observer. Whether I observe change or not, it happens. Whether I observe and measure length or not it exists. Lets take the opposite. Length does not exist without an observer. How does that even work? It would rewrite the entirely of measurement and physics. Its not an assumption that change exists independently of our observation, our observed outcomes could not work without this being true. It is a truth that has to be for the framework of an observer to even work.

You can absolutely logically claim that if observers weren't there, the measurements that they invented in themselves would not exist. But you haven't proven that what is concluded inside of the framework itself, that there is change which independently exists of our measurement, isn't necessary for the framework to work. That is why it is not an assumption that if you remove the measurement, that the independent thing being measured suddenly disappears. My point is that you get into a reductio ad absurdum, because then it means the independent thing we are measuring is not independent of us, but relies on our observation.

I think there’s a deeper issue lurking here. Absent any perspective whatever, what could it even mean to say that something “exists”? — Wayfarer

True, and I like this issue. Maybe you're just jumping to it a little too quickly or using an example that doesn't quite lead there. You don't need time to think about that. It applies to any observed concept. I think logically without language or thoughts, there can be nothing to say about existence.

Everything that we use is a model or representative of something independent of ourselves. And that independence is incomprehensible minus the fact that something contradicts us outside of our will, thoughts, and beliefs that proves something is out there that isn't us. But what we can't remove is the notion that there is something independent from us as an observer. If we remove that independence as an observer, our observations no longer work. And that is why it is not a presupposition that there is something independent of our observations. Its a necessary truth for us to be observers.

I feel I'm just repeating myself at this point. I largely agree with most of your premises.

Space and time are intrinsic to that discriminative capacity. Without spatial differentiation and temporal ordering, there could be no stable objects, no persistence, no comparison, no calculation — and therefore no measurement at all. Conscious awareness and intelligibility presuppose these structuring forms. — Wayfarer

Its just the difference of one small word. "Without spatial differentiation and temporal ordering, there could be no observation of stable objects...etc. ... Conscious awareness and intelligibility require these structuring forms. -

Metaphysician Undercover

14.9kThat’s actually on point. It’s very close to Bergson’s argument about clock time: what gets measured is not concrete duration itself, but an abstracted, spatialized parameter extracted for practical and mathematical purposes. Precision applies to the abstraction — not to the lived or concrete whole. But then, we substitute the abstract measurement for the lived sense of time. — Wayfarer

Metaphysician Undercover

14.9kThat’s actually on point. It’s very close to Bergson’s argument about clock time: what gets measured is not concrete duration itself, but an abstracted, spatialized parameter extracted for practical and mathematical purposes. Precision applies to the abstraction — not to the lived or concrete whole. But then, we substitute the abstract measurement for the lived sense of time. — Wayfarer

I believe this is exactly how the false, determinist representation of time is created. We create abstract "units" of time based on certain activities. The traditional activities are the motions of the earth relative to the sun, day, year. Now we use vibrations of atoms. All the units are totally abstract though, and mark length of "duration". Then we take these abstract units of duration, and assume that they are "the lived sense of time".

The problem is that as measured units of duration is not at all how we experience time. We experience time at the present, as a continuous position relative to a determined past and a future full of possibility. So duration is just an abstract tool we come up with, which is very useful for many purposes, but our true experience of time is not as duration at all. -

Gnomon

4.4k

Gnomon

4.4k

Maybe the difference, between your concept of Time, and Wayfarer's, can be demonstrated in a poster's screen-name : Esse quam videri*1 (to be rather than to seem). God-only-knows (metaphor) what actually IS, from a universal-eternal perspective. And a scientist or philosopher only sees (observes) a narrow view (to seem ; appearances) of Ontology. Neither perspective is fully objective. So we can only interpret sample measurements, and infer or imagine or guess how that evolving aspect of Being would appear to omniscience : its cosmic function and meaning. Einstein inadvertently summarized this distinction in his Theory of Relativity and the Block Universe model.We can measure this quantitatively with time, but the qualitative concepts still exist without our measurement or observation. — Philosophim

Therefore, as I interpret 's intent : we humans only know how Time seems (subjectively) to us star-gazing animals, who measure Change in terms of astronomical or historical events*2. But the universe is, compared to us earthlings, near infinite. Therefore, based on the incomplete information of our native senses, and our artificial extensions, we can only know how Time appears to us (subjective observers) from our ant-like perspective. Even methodical & mathematical Science can only approximate what Time is*3 for the practical purposes of dissecting reality. But overweening philosophers and cosmologers attempt to read the Mind of God.

Consequently, quantitative scientific-measurements-of-appearances, and qualitative philosophical-inferences-of-meaning only tell us --- "late arrivals in the long history of the universe" --- how Cosmic Change seems to us, not how it absolutely IS, beyond the scope of our measurements or meanings. Wayfarer openly acknowledges the practical utility of quantitative Time, but on this forum, prefers to focus on its qualitative features & functions : how it seems to time-bound eternity-imagining creatures. :smile:

*1. Esse quam videri is a Latin phrase meaning "To be, rather than to seem."

Note --- In this context, I interpret the phrase as a reference to Absolute ontological Truth (to be), as contrasted with Relative experiential truth (to seem).

*2. What is Time : In philosophy, time is explored as a fundamental dimension, a mental construct, or an illusion, with major debates focusing on whether it's an absolute container (Newton) or relative to events (Leibniz/Aristotle), and if only the present exists (Presentism) or past, present, and future are equally real (Eternalism), questioning its flow, reality, and relationship to change, consciousness, and space. It's viewed as the measure of change (Aristotle), a framework for our minds (Kant), or a feature of the illusory world (Advaita Vedanta), often contrasting physical time with our subjective experience.

https://www.google.com/search?client=firefox-b-1-d&q=philosophy+%3A+what+is+time

*3. In physics, time is a fundamental quantity measuring the progression of events, the interval over which change occurs, and a dimension in the spacetime continuum, treated as the fourth dimension. -

Philosophim

3.6kTherefore, as I interpret ↪Wayfarer's intent : we humans only know how Time seems (subjectively) to us star-gazing animals, who measure Change in terms of astronomical or historical events*2. But the universe is, compared to us earthlings, near infinite. — Gnomon

Philosophim

3.6kTherefore, as I interpret ↪Wayfarer's intent : we humans only know how Time seems (subjectively) to us star-gazing animals, who measure Change in terms of astronomical or historical events*2. But the universe is, compared to us earthlings, near infinite. — Gnomon

But we only know this within our frame of referents as observers. You're removing an observer, than adding something an observer would include back in.

Therefore, based on the incomplete information of our native senses, and our artificial extensions, we can only know how Time appears to us (subjective observers) from our ant-like perspective. Even methodical & mathematical Science can only approximate what Time is*3 for the practical purposes of dissecting reality. — Gnomon

Correct. Wayfarer and I are in agreement on this.

Consequently, quantitative scientific-measurements-of-appearances, and qualitative philosophical-inferences-of-meaning only tell us --- "late arrivals in the long history of the universe" --- how Cosmic Change seems to us, not how it absolutely IS, beyond the scope of our measurements or meanings. — Gnomon

Right, we are observers who measure what is independent of us. My point is that we cannot be observers without the notion of something independent that we observe. Under what logic can we say that if we remove observers, what is independent of us will also cease to be? The only logical thing we can conclude is that if observers were removed, that only the observer and the things they conclude would be removed, not the independent thing they were observing. Logically, time as a qualitative concept or 'change of states' would have to be as that is independent of us. Our measurement of that independent state would vanish, but not the independent state itself by definition.

So I am with Wayfarer on the concept of a universe without an observer being something that an observer cannot observe. That doesn't require there to be a lack of observers, that's happening now elsewhere in the universe. If nothing is independent of our observation, then there is nothing independent at all, and the notion of observation changes completely. -

Wayfarer

26.2kThe distinction made between a realm of becoming and the realm of eternity in early Greek thought is an interesting frame to consider.

Wayfarer

26.2kThe distinction made between a realm of becoming and the realm of eternity in early Greek thought is an interesting frame to consider.

Change becomes the most difficult thing to talk about. — Paine

Yes — that distinction really does go back to Parmenides, for whom 'the Real' can’t change without becoming unintelligible, which is why becoming is relegated to the realm of appearance. Plato and Aristotle both respond by trying, in different ways, to show how something can remain the same while still genuinely changing. This was the origin of much of Aristotle's metaphysics of universals.

There’s also an interesting modern echo in Andrie Linde’s point that a purely observer-independent picture of the universe tends toward a kind of thermodynamic “deadness,” where time and becoming drop out of the equations in quantum cosmology. Meaningful change only manifests relative to observers in non-equilibrium conditions - 'an observer with a clock, and the rest of the Universe', as he puts it. It feels like a contemporary version of the same old tension between being and becoming (see this interview.)

The independent existent we are measuring, does not overlook the role of the observing mind. — Philosophim

But it does! This is the basis of the major arguments about 'observer dependency' in quantum physics. Here are some excerpts from an influential paper, which has really entered the realm of popular science, John Wheeler's Law without Law, something I've quoted previously. Here is Wheeler's gloss on the measurement problem in quantum physics, and it really shows in a few words, how it had called Einstein's lifelong belief in the 'mind independence of reality' into question:

The dependence of what is observed upon the choice of the experimental arrangement made Einstein unhappy. It conflicts with the view that the universe exists "out there" independent of all acts of observation. In contrast, Bohr stressed that we confront here an inescapable new feature of nature, to be welcomed because of the understanding it gives us. In struggling to make clear to Einstein the central point as he saw it, Bohr found himself forced to introduce the word "phenomenon". In today's words, Bohr's point - and the central point of quantum theory - can be put into a simple sentence: "No elementary phenomenon is a phenomenon until it is a registered (observed) phenomenon".

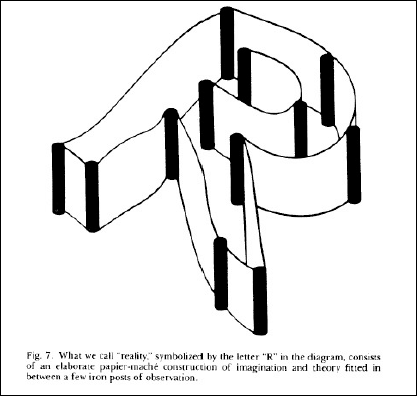

He also created this graphic to illustrate the point:

Caption reads: 'What we consider to be ‘reality’, symbolised by the letter R in the diagram, consists of an elaborate paper maché construction of imagination and theory fitted between a few iron posts of observation."

Notice this - the 'iron posts' are observations and measurements. But the shape of the R itself is a 'paper maché construction of imagination and theory'. That is what I mean by the way 'mind constructs reality'.

All this is elaborated in such books as Manjit Kumar. Quantum: Einstein, Bohr, and the Great Debate About the Nature of Reality. London: Icon Books; New York: W. W. Norton & Company, 2008 and David Lindley - Uncertainty: Einstein, Heisenberg, Bohr, and the Struggle for the Soul of Science. New York: Anchor Books/Random House, 2008. They make the centrality of the question of the 'mind-independence of reality' is central to these debates.

You can absolutely logically claim that if observers weren't there, the measurements that they invented in themselves would not exist. But you haven't proven that what is concluded inside of the framework itself, that there is change which independently exists of our measurement, isn't necessary for the framework to work. That is why it is not an assumption that if you remove the measurement, that the independent thing being measured suddenly disappears. — Philosophim

But the issue is, you can't stipulate anything about the 'independent thing' without bringing the mind to bear upon it. We know a lot about the early universe, before h.sapiens evolved, from cosmological science, geology and so on. But all of that is still structured within the framework the mind provides. You might say it was 'there all along' or 'there anyway' - but 'there' and 'anyway' are what the observer brings to the picture. This is what I mean by saying that there being an observer, nothing exists - not that does not exist, but neither does it exist, because there is no 'it'. Yes, when we discover 'it', we learn that it was there all along - but outside that framework, what is 'it'?

We don't notice that we're 'bringing the mind to bear' because that is the way that naturalism frames knowledge. There's the subject/observer, here, and the object/target, there, and never the twain shall meet.

I notice that you haven't actually commented on any of the philosophical arguments presented in the original post. I suggest that this is because you instinctively interpret the question through the frame of scientific realism. This is it intended as a pejorative statement, but as a way of understanding what the debate is about. Scientific realism is based on conviction of the reality of the observed world, and to question it is really a difficult thing to do. -

Philosophim

3.6kThe independent existent we are measuring, does not overlook the role of the observing mind.

Philosophim

3.6kThe independent existent we are measuring, does not overlook the role of the observing mind.

— Philosophim

But it does! This is the basis of the major arguments about 'observer dependency' in quantum physics. — Wayfarer

We have to be very careful when analyzing quantum physics as lay people because the language is not the common philosophical or even basic English phrasing we are comfortable with. It is a mathematical phrasing.

The reason we have to take the 'observer' into account, isn't our eyeballs or consciousness. Its our measuring tools. The quantum realm is so minute that the measuring tools we use to monitor the quantum state affect the state itself. Non-quantum measurement is like rolling a ping pong ball at a bowling ball. We bounce the ping pong ball off, then measure the velocity that the ball comes back to determine how solid the bowling ball is. The ping pong ball is rolled to not affect the movement of the bowling ball.

Quantum measurement reverses this. We are essentially pitching a bowling ball at a ping pong ball. Our measurements are always going to affect the outcome. Its why you can't know the velocity and location of the quantum object at the same time.

Scientists generally have pushed back against quantum equations as it is essentially probability equations. There is a need to know the exact location and velocity of every electron circling an atom, and yet we don't have the tooling to get that. Some take affront to this, 'giving up' on non-quantum specificity. Perhaps one day our tooling will get better and we will be able to measure and calculate with greater determinency. But for now this is what we have, and we can manipulate the limited states with probability to get outcomes in theory and practical application.

Bohr stressed that we confront here an inescapable new feature of nature, to be welcomed because of the understanding it gives us.

This is Bohr's point. Its about the math and accepting our measurement limitations.

Notice this - the 'iron posts' are observations and measurements. But the shape of the R itself is a 'paper maché construction of imagination and theory'. That is what I mean by the way 'mind constructs reality'. — Wayfarer

Correct, I understand your view point. My point is that its not the mind constructing reality, its the mind observing and creating a representative that is not contradicted by reality. Removing QM for a minute, lets just talk about the idea that there exists an R, but our measurement and observation only allow us to see those points on the R. That is how we model reality to our purposes. But the R still exists as a whole.

In general, models are as good as the needs of the one creating the model. Lets say that for our purposes, we can only see the points on the R, so what do we do? We make sure the model only makes assertions about those points, and not the points we can't observe. This is what I meant earlier by noting that science takes the observer into account when constructing models of reality.

But the issue is, you can't stipulate anything about the 'independent thing' without bringing the mind to bear upon it. — Wayfarer

Barring one thing: That it is independent. Meaning you are saying it exists apart from your observation. How? Who knows really. That's the definition of true independence. It does not depend in any way on your comprehension of it. You know it can exist in a way based on your tested and confirmed model. But how does it behave apart from that model? At that point, you can glean certain qualitative logic that necessarily must be from the working model. One being, "That is independent". Meaning it exists apart from observation. How exactly? Who knows. Its the "Thing in itself" problem from Kant. And it is a fascinating topic. I like your exploration of it here. My point is that if it is not independent, what does that logically mean? Does that break our current model use, our definition of observer, and everything we comprehend? It would seem to. Maybe it doesn't, and I was curious if you had given it thought and could propose what that would be like.

I notice that you haven't actually commented on any of the philosophical arguments presented in the original post. — Wayfarer

Didn't I address your citations and give a summary? Its been a few days since we started, is there something specifically you think I've missed as I've attempted to answer all of your follow ups from that.

Scientific realism is based on conviction of the reality of the observed world, and to question it is really a difficult thing to do. — Wayfarer

Science is not based on the conviction of the reality of the observed world. Its about what hypotheses have not been falsified yet. Science does not assert what it has discovered is truth. It asserts that the models it uses have not been proven false despite repeated tests, peer review, robust debate, and application. Scientific realism that asserts what has been found is truth, is flat out false. No disagreement here. The problem is that some scientific realists also take the common science standpoint, that it is an approximation to truth. This is in general why I shy away from broad categories and focus on the specific at hand. If your beef is purely with scientific realism that asserts our models are true representations of reality, I agree with you this cannot be logically asserted. -

Wayfarer

26.2kThe quantum realm is so minute that the measuring tools we use to monitor the quantum state affect the state itself. Non-quantum measurement is like rolling a ping pong ball at a bowling ball. We bounce the ping pong ball off, then measure the velocity that the ball comes back to determine how solid the bowling ball is. The ping pong ball is rolled to not affect the movement of the bowling ball. — Philosophim

Wayfarer

26.2kThe quantum realm is so minute that the measuring tools we use to monitor the quantum state affect the state itself. Non-quantum measurement is like rolling a ping pong ball at a bowling ball. We bounce the ping pong ball off, then measure the velocity that the ball comes back to determine how solid the bowling ball is. The ping pong ball is rolled to not affect the movement of the bowling ball. — Philosophim

Not so:

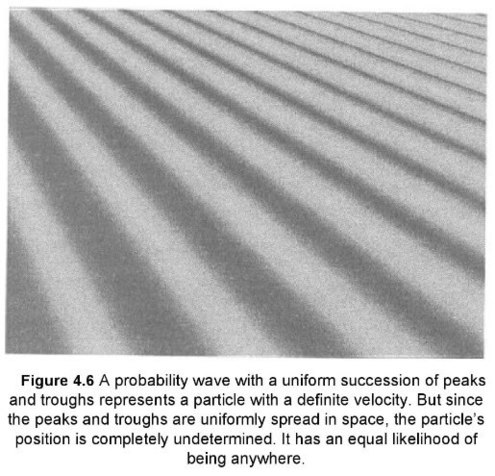

The explanation of uncertainty as arising through the unavoidable disturbance caused by the measurement process has provided physicists with a useful intuitive guide… . However, it can also be misleading. It may give the impression that uncertainty arises only when we lumbering experimenters meddle with things. This is not true. Uncertainty is built into the wave structure of quantum mechanics and exists whether or not we carry out some clumsy measurement. As an example, take a look at a particularly simple probability wave for a particle, the analog of a gently rolling ocean wave, shown in Figure 4.6.

Since the peaks are all uniformly moving to the right, you might guess that this wave describes a particle moving with the velocity of the wave peaks; experiments confirm that supposition. But where is the particle? Since the wave is uniformly spread throughout space, there is no way for us to say that the electron is here or there. When measured, it literally could be found anywhere. So while we know precisely how fast the particle is moving, there is huge uncertainty about its position. And as you see, this conclusion does not depend on our disturbing the particle. We never touched it. Instead, it relies on a basic feature of waves: they can be spread out. — Brian Greene, The Fabric of the Cosmos

There is a need to know the exact location and velocity of every electron circling an atom, and yet we don't have the tooling to get that — Philosophim

I'm sorry, but you're not seeing the real problem. The point of the uncertainty principle is that it's not a matter of 'tooling'. The uncertainty is genuine, as Brian Greene says above - a matter of principle. It is also true that scientific realists including Sir Roger Penrose don't accept this saying that there must be a better theory that hasn't been discovered yet. But I think that is far from a majority opinion. I acknowledge I'm not a physicist, but those references I mentioned (plus the Brian Greene one) do support what I'm saying.

But the issue is, you can't stipulate anything about the 'independent thing' without bringing the mind to bear upon it.

— Wayfarer

Barring one thing: That it is independent. Meaning you are saying it exists apart from your observation. How? Who knows really. That's the definition of true independence. It does not depend in any way on your comprehension of it. You know it can exist in a way based on your tested and confirmed model. But how does it behave apart from that model? At that point, you can glean certain qualitative logic that necessarily must be from the working model. One being, "That is independent". Meaning it exists apart from observation. How exactly? Who knows. Its the "Thing in itself" problem from Kant. And it is a fascinating topic. I like your exploration of it here. My point is that if it is not independent, what does that logically mean? Does that break our current model use, our definition of observer, and everything we comprehend? It would seem to. Maybe it doesn't, and I was curious if you had given it thought and could propose what that would be like. — Philosophim

I agree that this lands us very close to the “thing in itself” problem — but my own way of thinking about it probably leans more towards Buddhism.

What I mean is this: the “in itself” is what lies beyond our conceptual and sensory reach. It is not just unknown in practice; it is unknowable in principle insofar as any determination already brings the mind’s discriminations to bear. Even to say “it exists independently” is already to ascribe an ontological predicate to what is supposed to lie beyond all predication.

From that point of view, saying that the 'in-itself exists' is already a kind of over-specification — but saying that it does not exist is equally a mistake. Both moves bring in conceptual determinations into what is precisely not available to conceptual determination. We 'have something in mind'. That’s the sense in which 'it' is neither existent nor non-existent: not as a mysterious third thing, but because the existence / non-existence distinction itself belongs to the world as it is articulated for us.

So when you say “barring one thing: that it is independent,” I would hold off on that — not because I think the world collapses into subjectivism (ceases to exist outside my particular mind), but because “independence,” taken as an claim about reality in itself, is already a conceptual construction. What we actually encounter is constraint, resistance, regularity, surprise — all within experience and modelling. Independence as such is an abstraction we draw from that, not something we can meaningfully attribute to what lies beyond all possible description.

None of this breaks scientific models or the practical notion of an observer. Science continues exactly as before, operating perfectly well within the conventional domain of determinate objects, measurements, and laws. The point is only that when we try to step outside that domain and make ultimate claims about what reality is “in itself,” our concepts outrun their legitimate scope.

Bottom line: reality itself is not something we're outside of or apart from. We are participants in it, not simply observers on the outside of it. And that points towards an existential stance or way-of-being. -

Janus

18kWhat I mean is this: the “in itself” is what lies beyond our conceptual and sensory reach. It is not just unknown in practice; it is unknowable in principle insofar as any determination already brings the mind’s discriminations to bear. Even to say “it exists independently” is already to ascribe an ontological predicate to what is supposed to lie beyond all predication. — Wayfarer

Janus

18kWhat I mean is this: the “in itself” is what lies beyond our conceptual and sensory reach. It is not just unknown in practice; it is unknowable in principle insofar as any determination already brings the mind’s discriminations to bear. Even to say “it exists independently” is already to ascribe an ontological predicate to what is supposed to lie beyond all predication. — Wayfarer

You contradict yourself―you say "the in itself is what lies beyond our conceptual and sensory reach", which is the very definition of human mind-independence. Then you say we cannot predicate its independence. Make up your mind. Is there an itself? If there is it is utterly independent of our perceptions and consciousness.

If there isn't then the commonality of experience, the shared world cannot be explained, and we would be left with a mere inexplicable phenomenalism or else some form of realism that allows us epistemological access to ontically mind-independent reality. You need to be consistent in your thinking or else you are really saying nothing. -

Philosophim

3.6kI'll be quick on the quantum answer as I don't want to distract from your real point. The reason we measure as a wave vs an point is again a limitation of measurements. Lets go back to the waves of the ocean for example. We have no way of measuring each molecule in the wave, and even if we did, we would need a measurement system that didn't change the trajectory of the wave itself. I agree, its not all 'lumbering instruments', sometimes its just the limitation of specificity in measurement. Even then, such specificity is often impractical and unneeded. Fluid dynamics does not require us to measure the force of each atom.

Philosophim

3.6kI'll be quick on the quantum answer as I don't want to distract from your real point. The reason we measure as a wave vs an point is again a limitation of measurements. Lets go back to the waves of the ocean for example. We have no way of measuring each molecule in the wave, and even if we did, we would need a measurement system that didn't change the trajectory of the wave itself. I agree, its not all 'lumbering instruments', sometimes its just the limitation of specificity in measurement. Even then, such specificity is often impractical and unneeded. Fluid dynamics does not require us to measure the force of each atom.

Regardless, I feel that's not your true point.What I mean is this: the “in itself” is what lies beyond our conceptual and sensory reach. It is not just unknown in practice; it is unknowable in principle insofar as any determination already brings the mind’s discriminations to bear. Even to say “it exists independently” is already to ascribe an ontological predicate to what is supposed to lie beyond all predication. — Wayfarer

Yes, I understood that was what you were going for. And it is very appealing and powerful the first time you encounter it. But what is the next step after that?

From that point of view, saying that the 'in-itself exists' is already a kind of over-specification — but saying that it does not exist is equally a mistake. Both moves bring in conceptual determinations into what is precisely not available to conceptual determination. We 'have something in mind'. That’s the sense in which 'it' is neither existent nor non-existent: not as a mysterious third thing, but because the existence / non-existence distinction itself belongs to the world as it is articulated for us. — Wayfarer

And this is the quandry. You are completely correct stating 'exists in-itself' is overspecification. But then we can't deny that it exists, and that is the 'independent' part. Independent in this case is pure independence. Undefinable, unknowable, and yet exists separate from us. From my view point, the only way we glean that things apart from us exist is the contradiction of our belief vs 'experience'. If we keep as you noted " What we actually encounter is constraint, resistance, regularity, surprise — all within experience and modelling. Independence as such is an abstraction we draw from that, not something we can meaningfully attribute to what lies beyond all possible description." we logically descend into solipsism. But we know that solipsism doesn't rationally hold in experience either.

What I'm trying to note is that the 'thing in itself' does not exist as a 'thing'. It exists as a necessary concept that leads to absurdity without it. Its the affirmative of the 'thing in itself' its the denial of it that leads to contradictions. Its a reducto ad absurdum. And that is how we know it. Not because we 'know' it, but because claims that it doesn't exist are known to lead to contradictions.

None of this breaks scientific models or the practical notion of an observer. — Wayfarer

Only if we note that the 'thing in itself' is a necessarily logical concept, and nothing more. We have to be careful here when we assert that the 'thing in itself' could not exist without an observer. The language and everything we speak in needs the 'thing in itself' as a logical necessity. Remove that necessity, and the entirety of language and observation falls apart. That's the part I'm hoping to hear your ruminations on. Is there an alternative way of us as observers even having reason without this necessary logical concept?

Bottom line: reality itself is not something we're outside of or apart from. We are participants in it, not simply observers on the outside of it. — Wayfarer

100% agree. I know I've asked a few times, and I'll stop if you want. :) But I would be keen to hear your thoughts on my knowledge paper. I think you and I would agree on much of it, but your unique passion for the way humans construct knowledge might point out something I've missed. -

Wayfarer

26.2kIt's not a contradiction at all.

Wayfarer

26.2kIt's not a contradiction at all.

If there is, it is utterly independent of our perceptions and consciousness — Janus

Note the use of “is” and "it" here — “if there is X,” “if there is something unknown.” In designating it as a something, the grammar is already treating it as a determinate entity, when the whole point of the discussion is precisely that it is not even a thing in that sense. (In fact, this is where I think Kant errs in the expression 'ding an sich', 'thing-in-itself'. I think it would be better left as simply 'the in itself'.)

The phrase “in itself” is not meant to name a hidden object standing behind appearances, but to mark a limit: the point at which our concepts, predicates, and categories no longer legitimately apply. Once we start saying, of the in itself, that “it exists,” “it is independent,” “it has properties,” we have already introduced the very conceptual determinations that the notion of the in-itself was supposed to suspend. Remember this was Kant's argument against dogmatism (although I know you think that Kant was dogmatic.) But it should engender a genuine sense of not knowing.

That is why there is no contradiction in saying, on the one hand, that what reality is in itself lies beyond our conceptual and sensory reach, and on the other hand, that we cannot meaningfully predicate independence, existence, or non-existence of it. The first is a negative or limiting claim about the scope of cognition; the second is a refusal to reify that limit into a metaphysical object, a mysterious 'thing behind the thing.'

To insist that “if there is an in-itself, then it must be utterly independent” is already to assume the very issue under question — namely, that reality must be a kind of thing standing over against a mind, describable in abstraction from the conditions under which anything becomes intelligible at all.

None of this commits me to phenomenalism or to denying a shared world. We plainly inhabit a common world structured by stable regularities, constraints, resistance, error and correction. But those features belong to the world as it is disclosed within experience and inquiry, not to a metaphysical description of what reality supposedly is “in itself” apart from any standpoint whatsoever.

The deeper point is simply this: we are not outside reality looking in. We are participants within it. Treating the in-itself as a hidden object that either exists or does not exist already presupposes a spectator standpoint that the argument is calling into question.

Glad we have some points of agreement here and I appreciate the way you’ve framed this.

I agree entirely that something like a limiting or grounding function is logically indispensable. If we remove the idea that our experience is constrained by something not reducible to our beliefs or constructions, then reason, error, correction, and a shared world really do start to collapse. In that sense, I also agree that simply denying the “in itself” leads to incoherence.

Where I still want to be careful is about sliding from that logical indispensability to an ontological claim that what plays this limiting role therefore exists independently as some kind of determinate something — even if we immediately say it is unknowable or indefinable. My worry is that this quietly reintroduces the very reification the limit-concept was meant to address.

I’m not saying there’s a hidden thing behind the world that we can’t access. I’m saying that the fact we’re always inside reality — participating in it rather than standing outside it — means that our ways of describing it are never final or complete. Reality keeps pushing back on our concepts and forcing revision, but that doesn’t mean there’s a separate metaphysical object called “the in-itself.” The limit shows up in the openness and corrigibility of our own understanding, not as a mysterious thing beyond it.

So I’m not trying to remove the limit, but to interpret it differently: not as a hidden entity or substrate standing apart from us, but as a structural feature of our participation in reality — the fact that conceptual determination never closes upon itself, that experience is always constrained and corrigible without being exhaustively capturable in metaphysical predicates.

On that reading, reason, language, science, and intersubjective objectivity remain entirely intact. What drops out is only the picture of a fully observer-external reality that could, even in principle, be described as it is “in itself” from nowhere in particular. That seems to me a modest but important shift rather than a radical one.

With that, I offer another quote from the irascible but brilliant Arthur Schopenhauer, which I think makes the point that I was trying to press earlier, about how cogniive science validates aspects of philosophical idealism. The second sentence, in particular:

All that is objective, extended, active—that is to say, all that is material—is regarded by materialism as affording so solid a basis for its explanation, that a reduction of everything to this can leave nothing to be desired (especially if in ultimate analysis this reduction should resolve itself into action and reaction i.e. physics). But ...all this is given indirectly and in the highest degree determined, and is therefore merely a relatively present object, for it has passed through the machinery and manufactory of the brain, and has thus come under the forms of space, time and causality, by means of which it is first presented to us as extended in space and active in time. — Schopenhauer

And with that, I've said enough already, I need to log out for a few days to return to a writing project which is languishing for want of concentration. But thanks for those last questions and clarifications, I think the discussion has moved along. :pray: -

Janus

18kOnce we start saying, of the in itself, that “it exists,” “it is independent,” “it has properties,” we have already introduced the very conceptual determinations that the notion of the in-itself was supposed to suspend. — Wayfarer

Janus

18kOnce we start saying, of the in itself, that “it exists,” “it is independent,” “it has properties,” we have already introduced the very conceptual determinations that the notion of the in-itself was supposed to suspend. — Wayfarer

I don't see how you can escape the contradiction if you say

which is exactly to say that the in itself is human mind-independent.the “in itself” is what lies beyond our conceptual and sensory reach. — Wayfarer

Also, when you say "the in-itself is...whatever", you have posited it as something (not some thing of course) to which some predicate or even no predicate at all may be attached, and this devolves into incoherence because it makes the appearance of saying something while actually saying nothing at all.

You say I think Kant is dogmatic, and I do because Kant, having said we can say nothing about the in itself, inconsistently and illegitimately denies that the in itself is temporal, spatial or differentiated in any way, which is the same as to say it is either nothing at all or amorphous. He would be right to say that we cannot be sure as to what the spatiotemporal status of the in itself else, and that by very definition.

So I get that it can rightly be said that the in itself cannot be known to be spatial, temporal or differentiated in the ways that we understand from our experience inasmuch as we have defined it as being beyond experience, but it does stretch credibility to think that something which is either utterly amorphous or else nothing at all could give rise to the world of phenomena. Kant posits it simply on the logical grounds that if there are appearances then there must be something which appears.

The idea also depends on accepting that the in itself is completely inaccessible to us, but if it gives rise to the world of differentiated spatiotemporal phenomena, if phenomena depend upon it, then by definition we do have access to it, even if we do not have exhaustive access to it. On the other hand if it has nothing at all to do with sense experience then it is completely irrelevant and as good as nothing at all.

In any case, lack of certainty does not preclude reasoned speculation about the in itself, particularly if it is accepted that the phenomenal world of experience is dependent on the in itself. And note, you objected to the "it", but the "it" is already couched within the in itself. Much of what you say seems to come down to the attempt to play policeman to what we are allowed, not merely to claim or speculate, but to say coherently at all, and I do find that approach dogmatic. One persons' incoherence may be another's coherence.

I'm the first to admit that our understanding is limited by language, given its inherently dualistic nature. On the other hand our understanding is also facilitated by language. Our experience itself is, pre-linguistically, non-dual, and that experience plays a powerful part in our intuitive synthetic assessments of how things are. If we try to drill down strictly in analysis, we are always going to strike paradoxes, antinomies and aporia. So, I think a more playful, allusive kind of language is called for, free of the excessive concern with knowing whether we are strictly correct or not. Seek insight, not certainty. -

Tom Storm

10.9kYou say I think Kant is dogmatic, and I do because Kant, having said we can say nothing about the in itself, inconsistently and illegitimately denies that the in itself is temporal, spatial or differentiated in any way, which is the same as to say it is either nothing at all or amorphous. He would be right to say that we cannot be sure as to what the spatiotemporal status of the in itself else, and that by very definition. — Janus

Tom Storm

10.9kYou say I think Kant is dogmatic, and I do because Kant, having said we can say nothing about the in itself, inconsistently and illegitimately denies that the in itself is temporal, spatial or differentiated in any way, which is the same as to say it is either nothing at all or amorphous. He would be right to say that we cannot be sure as to what the spatiotemporal status of the in itself else, and that by very definition. — Janus

Yes, this tension could label Kant as dogmatic on noumena: he is meant to remain entirely agnostic, yet he slips into asserting what the noumenon cannot be, which, in effect, are claims about the thing-in-itself. Is this just one those performative contradictions many theories seem to generate? -

boundless

760I don’t want to give the impression that I doubt science’s capacity for extraordinary accuracy in the measurement of time (and distance). — Wayfarer

boundless

760I don’t want to give the impression that I doubt science’s capacity for extraordinary accuracy in the measurement of time (and distance). — Wayfarer

Yes, I know.

The point is that this quietly undermines the assumption that what is real independently of any observer can serve as the criterion for what truly exists. That move smuggles in a standpoint that no observer can actually occupy. It’s a subtle point — but also a modest one. It doesn't over-reach. — Wayfarer

It seems to me that you're saying that the intelligible structure of the empirical world comes from the interaction between the subject and the world. From this interaction, you get the empirical world with its intelligible structure. OK.

However, this clearly raises the question of how the subjects come into being, if you also accept that the subjects are contingent (i.e. that both their existence and their non-existence is a possibility). If you say that there is an explanation of their coming into being (albeit perhaps unknowable for us) you would say that there intelligibility 'prior' (not necessarily in a temporal sense of the word) to the subjects, i.e. independent from them. If, however, you say that there is no explanation (even if unkowable for us) for their coming into being, you have either to admit that (1) independendently from the subject the world isn't intelligible and therefore the coming into being of the subjects is also unintelligible which, however, would raise the question of how consistent such a claim can be or (2) that intelligibilty simply doesn't apply outside the context of the subjects and the problems that a view like (1) would raise do not apply because ultimately there are no subjects (i.e. non-dualism).

In other words, the 'weaker', non-committal view is IMO unstable. It either 'degenerates' into an indirect realism in which the world independently of the subjects has an intelligible structure. Or it 'degenerates' into a non-dualist view in which, ultimately, the subjects, the empirical worlds and so on are seen as ultimately illusory. -

Ludwig V

2.5k

Ludwig V

2.5k

Ok. I must admit, I have never thought of it as a knock-down argument. Perhaps that's because I don't really believe that such things really exist. in this case, it seems like a mere assertion, which I expected you to challenge directly. I did have my reply to your reply ready, but I guess you've taken the discussion in a different direction.Presuming anything is the act of a conscious being, so it is certain that presumption of the physical world presupposes a conscious being. But we know that the physical world existed long before any conscious beings existed (at least on this planet) and, since we know of no conscious beings that exist without a physical substrate, we can be sure that the physical world can exist without any conscious beings in it.

— Ludwig V

This is a popular and seemingly knock-down objection to philosophical idealism. After all, how could the mind (or the observer, or consciousness) be fundamental to reality, as such, when rational sentient beings such as ourselves (and ours are the only minds we know of) are such late arrivals in the long history of the universe?

It is this line of argument that is to be scrutinised here (sc. in the thread "About Time. — Wayfarer

From my point of view, this is a case study of the concept of time to clarify the idealist thesis in general. In a way, I think case-by-case is a much more appropriate way to approach the question.

No. I was expecting a challenge on that point. One aim in the argument was to demonstrate that our language is constituted to identify and describe objects that exist indepdently of it. Indeed, these are so pervasive that we are often deceived into thinking that a language-independent reality is being described, when it isn't. So the distinction is not always obvious.You haven't presented evidence that the world did not exist prior to consciousness. The only thing you've observed is that humans have measured change with units we call time, and you think that if there isn't a consciousness measuring change that change cannot happen. That's a big claim with nothing backed behind it. — Philosophim

There are other clues. In (modern) science, the methodological importance attached to experiments and observations depends entirely on the fact that they provided independent evidence that posited laws are correct or need amendment.

Well, its good to see that we agree on so much. But then, I wonder what we disagree about. Berkeley makes a similar claim, which, at first sight, prompts the same issue. In his case, tracking the shifts in the meaning of the crucial terms is a fascinating exercise and can only increase one's respect for him.To begin with, it is important to be clear about what is not at issue. I am entirely confident that the broad outlines of cosmological, geological, and biological evolution developed by current science are correct, even if many of the details remain open to revision. I have no time (irony intended) for the various forms of science denialism or creationist mythology that question its veracity. I am well acquainted with evolutionary theory as it applies to h.sapiens, and I see no reason to contest it. — Wayfarer

"Constitution" is, I gather, a bit of a term of art in philosophy. It seems to mean the process by means of which we make things up, construct them. So your thesis is that we construct time.What the following argument turns on instead is the role of the observer in the constitution of time. — Wayfarer

This seems to be an acknowledgement of something that is observer-independent. But you suggest a different conception of time, which includes, what mere change, you say, doesn't include - succession or before-and-after or duration.So the claim is not that change requires an observer, but that time as succession—as a unified before-and-after—does. Without such a standpoint, we still have physical processes, but not time understood as passage or duration. — Wayfarer

Physics relates states to one another using a time parameter. What it does not supply by itself is the continuity that makes those states intelligible as a passage from earlier to later. I don't understand this. Every morning, the sun rises, then it moves across the sky and finally sets. That seems like succession and continuity to me. The dawn is before noon and dusk is after noon.

However, I do accept that developing clocks changes things radically. — Wayfarer

I'm afraid you may have been hypnotized by the traditional clock-work (!) clock. But the first clock (and calendar) was (most likely) the sun. However, the moon also acts as a measure, and we have, for example, water-clocks and candle-clocks as well as electric clocks that do not tick. In fact, the ticking clock is also a process of change in the world and not really any different from any other clock.A clock records discrete states; it does not experience their succession as a continuous series amounting duration. The fact that we can say “one second has passed” already presupposes a standpoint from which distinct states are apprehended as belonging to a single, continuous temporal order. — Wayfarer

So what is measured is a process in the mind-independent world and the measure is a process in the mind-independent world. Our contribution is to enable more accurate measurement; it does not create of constitute anything (except some units of measurement).

But the fact that we can compare any process with any other can create an illusion - that there is some absolute process with which any other process can be compared - absolute time and absolute space which exists independently of any actual objects or processes. But the concept of empty space and empty time is the result of our ability to compare processes and objects in certain respects and our ability to create an abstract framework for them. That's all. -

Corvus

4.8k

Corvus

4.8k

You misunderstood my point. I never said or implied, just 2 folks agreeing on something is objective. My idea of objectivity means - widely or officially accepted by scientific tradition or customs in the world.Well, "objective" has many meanings. Here, you imply that if two people agree, then it is "objective". That would imply a meaning of "objective" which is based in intersubjectivity. So, when I said the measurement is "subjective", this is not inconsistent, or contrary to your use of "objective" here. — Metaphysician Undercover

Size, weight, distance and duration has no meaning without measurements for them. I have never said they are objects. Again you seem to have misunderstood my points.You ignored the point I made. "Size", "weight", etc., are not "the object", those terms refer to a specific feature, a property of the supposed object, and strictly speaking it is that specific property which is measured, not the object. — Metaphysician Undercover -

Corvus

4.8kSo measurement is twice removed from the object. It is not a property of the object, but a property of the property. It is an idea applied to an idea, therefore subjective. — Metaphysician Undercover

Corvus

4.8kSo measurement is twice removed from the object. It is not a property of the object, but a property of the property. It is an idea applied to an idea, therefore subjective. — Metaphysician Undercover

Measurement is not idea. It is reading of the objects in number. Numeric value read by the instruments i.e in case of time or duration, it would be stop watch or clock. The instruments are set for the universal reading methods in numeric value, which is objective knowledge on the objects. -

Corvus

4.8kThe point I made is that if we adhere to a strict definition of "objective", meaning of the object, then measurement is not objective. This is because measurement assigns a value to a specified property, it does not say anything about the object itself. Assigning the property to the object says something about the object, but assigning a value to the property says something about the property. — Metaphysician Undercover

Corvus

4.8kThe point I made is that if we adhere to a strict definition of "objective", meaning of the object, then measurement is not objective. This is because measurement assigns a value to a specified property, it does not say anything about the object itself. Assigning the property to the object says something about the object, but assigning a value to the property says something about the property. — Metaphysician Undercover

Your confusion seems to be coming from the fact that you misunderstands the idea of "measurement". Please read the proper definition from my previous post. It is not property of property. Measurement is always in numeric value of the objects read by the instruments. -

Philosophim

3.6kNote the use of “is” and "it" here — “if there is X,” “if there is something unknown.” In designating it as a something, the grammar is already treating it as a determinate entity, when the whole point of the discussion is precisely that it is not even a thing in that sense. (In fact, this is where I think Kant errs in the expression 'ding an sich', 'thing-in-itself'. I think it would be better left as simply 'the in itself'.) — Wayfarer

Philosophim

3.6kNote the use of “is” and "it" here — “if there is X,” “if there is something unknown.” In designating it as a something, the grammar is already treating it as a determinate entity, when the whole point of the discussion is precisely that it is not even a thing in that sense. (In fact, this is where I think Kant errs in the expression 'ding an sich', 'thing-in-itself'. I think it would be better left as simply 'the in itself'.) — Wayfarer

I get your point. I think the difference between ourselves is I see it as a known unknown. We're probably getting into the 'agree to disagree' territory. Its a fair debate, but you understand what I'm noting, I think I understand what you're noting, and that's the important thing here.

The deeper point is simply this: we are not outside reality looking in. We are participants within it. Treating the in-itself as a hidden object that either exists or does not exist already presupposes a spectator standpoint that the argument is calling into question. — Wayfarer

I think another thing here is that I believe both to be true. We are both participants, but outsiders also looking in. The 'outsiders looking in' part is a role we participate in, and in creating the model's we do we formulate terms and concepts that would themselves not exist. Let me paint a fun picture for you that we see an elephant walking around. Unknown to us, its an Eldritch horror of 6 dimensions. But since we can't experience 6 dimensions, our model is not contradicted by the 4D experiences we have with the animal, and it works objectively for us.

'The in itself' is a variation of the evil demon and the brain in a vat. It is the question of, "What is it like to be a bat?" It is the known unknowable that vexes some and creates wonderment in others. As I referenced above, I always wondered if HP Lovecraft viewed it as 'the forbidden knowledge that man was not means to understand, and would drive them mad if they did'.

To insist that “if there is an in-itself, then it must be utterly independent” is already to assume the very issue under question — namely, that reality must be a kind of thing standing over against a mind, describable in abstraction from the conditions under which anything becomes intelligible at all. — Wayfarer

I won't repeat in detail on this, just a brief mention that I think this is our main disagreement. Part of the wonder of human accomplishment isn't just knowing things, it is knowing the limits to things and logically putting together possibilities that apply to reality correctly. That's quantum mechanics and chaos theory. Its sitting on a logic puzzle and figuring out the last x,y check mark based purely on the fact that you've eliminated all other possibilities from the clues given. It is logically known only. We know where that election is, but we don't know what velocity it will travel in next. We know the limits of where a lightning bolt can land, but not exactly where it will. And sure, Jane has the walrus, but we've never seen Jane nor the Walrus.

Glad we have some points of agreement here and I appreciate the way you’ve framed this. — Wayfarer

Same. Also, you created a very well written essay and counterpoints.

Where I still want to be careful is about sliding from that logical indispensability to an ontological claim that what plays this limiting role therefore exists independently as some kind of determinate something — even if we immediately say it is unknowable or indefinable. My worry is that this quietly reintroduces the very reification the limit-concept was meant to address. — Wayfarer

This is a good point. For all we know, it could be an indeterminate 'thing/event'. That is why for me the only thing I think we can logically assert is 'independence'. It is something completely independent from us, and as such exists apart from us. It is 'the behind' of our observations. The temptation to add more knowledge claims than this is always there, but the bar is set high and rarely met by the inductions thrown at it.

I’m not saying there’s a hidden thing behind the world that we can’t access. I’m saying that the fact we’re always inside reality — participating in it rather than standing outside it — means that our ways of describing it are never final or complete. Reality keeps pushing back on our concepts and forcing revision, but that doesn’t mean there’s a separate metaphysical object called “the in-itself.” The limit shows up in the openness and corrigibility of our own understanding, not as a mysterious thing beyond it. — Wayfarer

I find it amusing that we both are using nearly identical language, but it is only a matter of perspective that separates. I find this to be a common thing in epistemology as people gaze into the 'known unknown'. I agree, when we assert 'the in itself' its not 'an object'. Its not a claim to "There's Jane in the flesh", its a claim that there is something with the quality of independence from ourselves, and that's the limit of what we can know.

So I’m not trying to remove the limit, but to interpret it differently: not as a hidden entity or substrate standing apart from us, but as a structural feature of our participation in reality — the fact that conceptual determination never closes upon itself, that experience is always constrained and corrigible without being exhaustively capturable in metaphysical predicates. — Wayfarer

Agreed. I do think there is a logical way to navigate through this uncertainty, and that logical navigation is proper deductive an inductive application. As such we can find logical models that work, but its understood that the logical models are not claims to understand independent reality 'in itself'.

And with that, I've said enough already, I need to log out for a few days to return to a writing project which is languishing for want of concentration. But thanks for those last questions and clarifications, I think the discussion has moved along. — Wayfarer

Yes, thanks as well Wayfarer! I wish you clear thoughts and limber hands. -

Mww

5.4kMany things seem to share the same space, and that becomes problematic for physics. — Metaphysician Undercover

Mww

5.4kMany things seem to share the same space, and that becomes problematic for physics. — Metaphysician Undercover

True enough, but my response would be….my experiences are not on so small a scale. I remember reading…a million years ago it seems….if the nucleus of a hydrogen atom was the size of a basketball, and it was placing on the 50yd-line of a standard American football field, its electron’s orbit would be outside the stadium. Point being, there’s plenty of room for particles to share without bumping into each other. And even if the science at this scale says something different, it remains a fact I can’t seem to get two candles to fit in the same holder without FUBARing both of ‘em.

Another way to look at the overall problem of distinctions and differences, and more of my particular interest: find out what the rules are, let the sufficiently related exceptions to those rules be what they may.

—————-

….you accept the idea that intelligibility doesn't come from the subject? — boundless

Yes. Intelligence comes from the subject; intelligibility is that to which the subject’s intelligence responds.

—————-

….this tension could label Kant as dogmatic on noumena… — Tom Storm

Noumena being altogether irrelevant, Kant labels himself as dogmatic, that is, to be dogmatic is to prove conclusions from “secure principles” a priori (Bxxxv). Technically, it is reason itself that is dogmatic.

The subject himself, on the other hand in the use of his reason, engages in dogmatism in its “loquacious shallowness under the presumed name of popularity”…. ibid

(The regular run-of-the-mill genius Prussian academic’s way of saying, hey, don’t gimme that look; I’m just repeating what I been told)

…..but in dogmatism is technically using “philosophical concepts according to principles which reason has been using for a long time without first inquiring in what way and by what right it has obtained them.” (ibid

And how, you ask, and I know you are….doesn’t everyone?…..is the way obtained and the right secured, for these principle’s use as dogmatically conclusive proofs? Why, from the critique of pure reason, of course.

And there’s more. Oh so much more.

—————-

….he is meant to remain entirely agnostic, yet he slips into asserting what the noumenon cannot be…. — Tom Storm

He is perfectly justified in asserting what a thing is not, without ever knowing what it is. A thing is or is not (this or that) iff it does or does not conform to the relevant principles the critique of pure reason as shown to be rightfully secure. From which follows, a noumenon is in every way and by every right a valid conception according to the principles by which any conception is possible, but in no way and not by any right at all, is anything to be known of it, according to those principles by which knowledge is possible.

All that is mainly responsible for the advent of analytical philosophy, re: the attempt to relegate systemic speculative metaphysics to practical nonsense, insofar as the proofs are all logical, conditioned by premises, rather than empirical, conditioned by observation.

Over ’n’ out. -

Metaphysician Undercover

14.9kI'll be quick on the quantum answer as I don't want to distract from your real point. The reason we measure as a wave vs an point is again a limitation of measurements. Lets go back to the waves of the ocean for example. We have no way of measuring each molecule in the wave, and even if we did, we would need a measurement system that didn't change the trajectory of the wave itself. I agree, its not all 'lumbering instruments', sometimes its just the limitation of specificity in measurement. Even then, such specificity is often impractical and unneeded. Fluid dynamics does not require us to measure the force of each atom. — Philosophim

Metaphysician Undercover

14.9kI'll be quick on the quantum answer as I don't want to distract from your real point. The reason we measure as a wave vs an point is again a limitation of measurements. Lets go back to the waves of the ocean for example. We have no way of measuring each molecule in the wave, and even if we did, we would need a measurement system that didn't change the trajectory of the wave itself. I agree, its not all 'lumbering instruments', sometimes its just the limitation of specificity in measurement. Even then, such specificity is often impractical and unneeded. Fluid dynamics does not require us to measure the force of each atom. — Philosophim

I don't think your analogy works. Particles like photons and electrons, in their relation to electromagnetic waves, are not analogous to water molecules in their relation to ocean waves. The waves in water are composed of molecules, and the movement of these particles comprises the visible wave activity. The case of electromagnetic waves is completely different. The observed wave activity is not comprised of underlying particles. And although the energy is known to be transmitted as wave activity, the transmitted energy can only be measured as particles. This is not an issue of limited specificity, it is an issue having no understanding of the relationship between the material particle which is measured, and the immaterial wave which cannot actually be measured.

You say I think Kant is dogmatic, and I do because Kant, having said we can say nothing about the in itself, inconsistently and illegitimately denies that the in itself is temporal, spatial or differentiated in any way, which is the same as to say it is either nothing at all or amorphous. He would be right to say that we cannot be sure as to what the spatiotemporal status of the in itself else, and that by very definition. — Janus

I think you misunderstand Kant. Since space and time are a priori intuitions, these two are proposed as the conditions for sense appearances which are internal to the human being. Therefore the proposed "in itself" cannot have any "spatiotemporal status". You talk as if it would be consistent with Kant to assign to the in itself, a spatiotemporal status which we cannot understand. That is an incorrect interpretation, because by Kant's principles we cannot describe things such that the in itself can even be said to have a spatiotemporal status. The spatial temporal status is a creation of thiose intuitions.

This is not inconsistent, or illegitimate at all. His claim is that space and time are conditionings which the human body imposes, therefore it would be wrong to think that the in itself would be composed of them. Take the map/territory analogy for example. The intuitions of space and time are part of the map. Even though the symbols on the map are intended to represent some aspect of the territory, it would be wrong to assume that you could go out and find those very symbols existing in the territory. In the same way, Kant implies that it would be wrong to think that there is space and time in the in itself.

So I get that it can rightly be said that the in itself cannot be known to be spatial, temporal or differentiated in the ways that we understand from our experience inasmuch as we have defined it as being beyond experience, but it does stretch credibility to think that something which is either utterly amorphous or else nothing at all could give rise to the world of phenomena. Kant posits it simply on the logical grounds that if there are appearances then there must be something which appears. — Janus

This does not "stretch credibility". Living beings are known to be creative beings. It ought not appear to you as "incredible" that they have created these a priori intuitions of space and time, as useful in their living ventures. Further, it ought not seem unreasonable to you, that the symbols used by a living being may not be in any way similar to the thing symbolized. Does the word "symbol" to you, appear to be in any way similar to what the symbol means or refers to. Likewise, the sense representations produced through the means of the intuitions of space and time, may not be in any way similar to the in itself.

You misunderstood my point. I never said or implied, just 2 folks agreeing on something is objective. My idea of objectivity means - widely or officially accepted by scientific tradition or customs in the world. — Corvus

The issue of the difference between true and justified remains. That a principle is "officially accepted by scientific tradition or customs in the world" implies that it is justified, but it might still be false. If "objective knowledge" requires justification and truth, then "officially accepted by scientific tradition or customs in the world", is insufficient for "objectivity" because the condition of truth is not there. So your proposed definition of "objective" cannot be accepted.

Measurement is not idea. It is reading of the objects in number. Numeric value read by the instruments i.e in case of time or duration, it would be stop watch or clock. The instruments are set for the universal reading methods in numeric value, which is objective knowledge on the objects. — Corvus

I'm sorry Corvus, but this line, ("It is reading of the objects in number") makes no sense to me at all. How could a person read an object, unless it was written language like a book. Are you suggesting that you, or an instrument, could look at an object and see numerals printed on it, and interpreting these numerals forms a measurement? That's craziness.

Your confusion seems to be coming from the fact that you misunderstands the ideas of "measurement". Please read the proper definition from my previous post. It is not property of property. Measurement is always in numeric value of the objects read by the instruments. — Corvus

Yikes! You seem to believe in that craziness.

True enough, but my response would be….my experiences are not on so small a scale. I remember reading…a million years ago it seems….if the nucleus of a hydrogen atom was the size of a basketball, and it was placing on the 50yd-line of a standard American football field, its electron’s orbit would be outside the stadium. Point being, there’s plenty of room for particles to share without bumping into each other. And even if the science at this scale says something different, it remains a fact I can’t seem to get two candles to fit in the same holder without FUBARing both of ‘em. — Mww

I believe that this idea, this common instinct or intuition, that two things cannot occupy the same space at the same time, significantly misleads us in our understanding of the world.

The problem is that we place far too much emphasis on what is seen. so when a multitude of things exist at the same place, we see them as one, and think that there is only one thing there. But if we understand a thing as consisting of fields (for example) then we understand that there is always an overlapping of multiple fields, existing at the same place.

The light from the sun for example, is a field, and the earth is within this field. So the sun and the earth exist in the very same place, as a single object, the solar system, just like the hydrogen atom nucleus and its electron exist at the same place, as the atom. We cannot separate the two, to say that they occupy different places, because it is essential to the atom's existence, as a thing, an object, that their fields overlap each other, interacting with each other, to have a multitude of things existing together at the same place, with the appearance that they are one united thing.

This way of looking at things becomes very clear in a hierarchical model. From one direction to another, some levels may be entirely subsumed within another to to exist completely within that one, whereas some just overlap like Venn diagrams. This is the way we understand the existence of conceptions, logically, like a sort of set theory sometimes. One concept may be entirely within another, and this produces logical priority. -

Corvus

4.8k

Corvus

4.8k

It sounds crazy to me if someone cannot read numbers on the speedo meter or watch. Do you mean you can only read English words, but not numbers?I'm sorry Corvus, but this line, ("It is reading of the objects in number") makes no sense to me at all. How could a person read an object, unless it was written language like a book. Are you suggesting that you, or an instrument, could look at an object and see numerals printed on it, and interpreting these numerals forms a measurement? That's craziness. — Metaphysician Undercover