-

Manuel

4.4kAfter spending considerable time thinking and reading on the topic, it is almost as obscure now as it was before I focused on it.

Manuel

4.4kAfter spending considerable time thinking and reading on the topic, it is almost as obscure now as it was before I focused on it.

Avoiding new age stuff, I believe the most accurate thing to say about metaphysics is that it focuses on the nature of the world and attempts to capture something in it that applies to all possible experience. It's always on the verge of attempting to say something very rudimentary of what lies beyond experience too. But this last point is like swimming in lava.

So, in short, I don't think it's easy to answer this. -

Wayfarer

26.2kDo you think there is one kind of metaphysics under the disguises in different cultures? And how would that look like? Like your vision of it? — Prishon

Wayfarer

26.2kDo you think there is one kind of metaphysics under the disguises in different cultures? And how would that look like? Like your vision of it? — Prishon

There are different schools of thought about metaphysics. My comment was more about the common belief that metaphysics has been superseded or rendered obsolete. The same problems which gave rise to metaphysics in the first place don't actually go away, they tend to re-appear in new forms. -

180 Proof

16.4k

180 Proof

16.4k

:up: I Agree.Avoiding new age stuff ... [Metaphysics] always on the verge of attempting to say something very rudimentary of what lies beyond experience too. But this last point is like swimming in lava.

So, in short, I don't think it's easy to answer this. — Manuel

I don't think so. Maybe for philosophical materialists the 'problem of consciousness' is intractably "hard" but not for methodological materialists (e.g. neuroscientists, cognitive psychologists, et al) as I point out here:The "Hard Problem" is hard for those who think in terms of Materialism. — Gnomon

https://thephilosophyforum.com/discussion/comment/511358. -

Wayfarer

26.2kphilosophy itself is not (equipped to effectively engage) in the 'theoretical explanation' business. — 180 Proof

Wayfarer

26.2kphilosophy itself is not (equipped to effectively engage) in the 'theoretical explanation' business. — 180 Proof

Well, that's exactly the business that 'natural philosophy' is in, isn't it? Why are the ice sheets melting? Because of increasing CO2 in the atmosphere. And so on.

The observation by Wittgenstein that I think you're referring to in the other post you link to are these:

6.41 The sense of the world must lie outside the world. In the world

everything is as it is, and everything happens as it does happen: in it no

value exists--and if it did exist, it would have no value. If there is any

value that does have value, it must lie outside the whole sphere of what

happens and is the case. For all that happens and is the case is

accidental. What makes it non-accidental cannot lie within the world, since

if it did it would itself be accidental. It must lie outside the world.

6.42 So too it is impossible for there to be propositions of ethics.

Propositions can express nothing that is higher.

6.421 It is clear that ethics cannot be put into words. Ethics is

transcendental. (Ethics and aesthetics are one and the same.)

So, note, he's not saying that philosophy doesn't provide theoretical explanations for anything whatever, but for values, in particular. There's a strongly Platonist flavour to this set of passages, in that they suggest that ethics and aesthetics - the Good and the Beautiful - are on a different plane to factual statements about states of affairs.

Propositions can't express anything that is higher, because of the nature of discursive reasoning, not because there isn't anything higher.

The most straight-forward expression of methdological materialism is behaviourism, which excludes consideration of mind altogether. Eliminative materialists are their descendants. (Dennett acknowledges this, somewhere.)

The error which I think Wittgenstein is calling out, is the belief that methodological naturalism has anything to say about ethics and aesthetics. It can't, because it rules out consideration of such things as a methodological step. But that doesn't mean what the logical positivists took it to mean, as explained in this essay. -

180 Proof

16.4kI can't think of a significant methodological materialist who is a mere (Skinnerian) behaviorist. Witty has little to nothing to do with my stated position (re: science), by the way; much more Peirce and Dewey, Popper and Feyerabend, Sellars and Dennett, et al. Again, Woofarer, you're barking at strawmen's shadows. Also, climatologists, not "natural philosophers", have modeled and predicted anthropogenic climate change. Wtf are you glossolaling about, sir? :roll:

180 Proof

16.4kI can't think of a significant methodological materialist who is a mere (Skinnerian) behaviorist. Witty has little to nothing to do with my stated position (re: science), by the way; much more Peirce and Dewey, Popper and Feyerabend, Sellars and Dennett, et al. Again, Woofarer, you're barking at strawmen's shadows. Also, climatologists, not "natural philosophers", have modeled and predicted anthropogenic climate change. Wtf are you glossolaling about, sir? :roll: -

Wayfarer

26.2kWhenever you can't answer an argument, you fall back to ad homs and accusations of 'straw men' which means you don't understand the criticism. I've been reading your postings for 10 years, I know exactly where you're at.

Wayfarer

26.2kWhenever you can't answer an argument, you fall back to ad homs and accusations of 'straw men' which means you don't understand the criticism. I've been reading your postings for 10 years, I know exactly where you're at.

To re-iterate - methodological naturalism excludes consideration of metaphysics, wherever possible, as a matter of practice. It's seeking explanations in terms of attributable causes and effects, and in terms of natural principles ('laws'). But excluding consideration of metaphysics is not the same as saying, as logical positivism does, that metaphysical statements are nonsense (although the best you can do is bluster on about 'woo'.) -

Shawn

13.5kPropositions can't express anything that is higher, because of the nature of discursive reasoning, not because there isn't anything higher. — Wayfarer

Shawn

13.5kPropositions can't express anything that is higher, because of the nature of discursive reasoning, not because there isn't anything higher. — Wayfarer

Actually, the highest a proposition can express is self-hood, by recursion. So, there is potential to build off of self-referential statements to talk about what it doesn't envelop.

The error which I think Wittgenstein is calling out, is the belief that methodological naturalism has anything to say about ethics and aesthetics. It can't, because it rules out consideration of such things as a methodological step. But that doesn't mean what the logical positivists took it to mean, as explained in this essay. — Wayfarer

I just read that essay, and the logical positivists had a point about nonsense speaking about ethics, as Wittgenstein would call it. Funny enough it really doesn't come off as nonsense.

And we do talk about aesthetics every day or state opinions about differing values. So, the mystical is in the differences, not the apparent. -

180 Proof

16.4kAgain, besides repeating what I've said countless times (re: distinction between methodological & philosophical, which you often conflate), wtf are you babbling about? (Rhetorical question, spare me more non sequiturs.) Yeah, I call you out when you object to statements or claims I have not made. Those are strawmen. This knack, or gag-reflex, of yours is probably why you won't debate me – you refuse to address what your interlocators actually say when they disagree with or criticize your woo.

180 Proof

16.4kAgain, besides repeating what I've said countless times (re: distinction between methodological & philosophical, which you often conflate), wtf are you babbling about? (Rhetorical question, spare me more non sequiturs.) Yeah, I call you out when you object to statements or claims I have not made. Those are strawmen. This knack, or gag-reflex, of yours is probably why you won't debate me – you refuse to address what your interlocators actually say when they disagree with or criticize your woo. -

Wayfarer

26.2kwtf are you babbling about. — 180 Proof

Wayfarer

26.2kwtf are you babbling about. — 180 Proof

Your remark:

philosophy itself is not (equipped to effectively engage) in the 'theoretical explanation' business. — 180 Proof

(re: distinction between methodological & philosophical, which you often conflate), — 180 Proof

Philosophy and science both are often engaged in exploring theoretical explanations. Naturalism seeks explanations which are based on observable facts of nature. Methodological naturalism eschews explanations which are not observable in nature, or derived from observations of natural phenomena. Metaphysical naturalism goes further, and claims that there is nothing significant beyond what can be observed in nature or derived from observations about nature. That attitude is what is generally known as positivism. As the article I linked to comments, the Vienna Circle positivists misinterpreted Wittgenstein's intent in this regard. (That's 'the folly' in the essay title.)

because philosophizing, as Witty et al point out, does not explain matters of facts — 180 Proof

How does that mitigate against Chalmer's contention that 'the problem of subjective experience' is a hard problem, because it's not amenable to objective explication? That no amount of objective description can capture or convey 'what it is like' to be the subject of experience. Isn't Wittgenstein, therefore, closer in spirit to David Chalmers, than to those you cite who believe that there can be such an objective explanation?

And don't accuse me of not answering you, when whenever I respond, I am hit with 'woofarer' and 'strawman' which is all bluff and bluster on your part. If you can't do better than ad homs and bluster, then really why should I bother? -

TheMadFool

13.8kMetaphysics is the branch of philosophy that studies the first principles of being, identity and change, space and time, causality, necessity and possibility. It includes questions about the nature of consciousness and the relationship between mind and matter. — Wikipedia

Now, from the above, "definition", it might appear that there's an essence to metaphysics but I don't think there's one because the term was simply a label for what followed physics in Aristotle's body of works and it was an assortment of topics that weren't in any way unified by a common theme. Metaphysics is just a fancy way of saying miscellaneous. -

Gnomon

4.3k

Gnomon

4.3k

I'm guessing that the age-old question of Consciousness is not a major problem for "methodical materialists" because they don't concern themselves with Qualia, being content to focus on Quanta. Feynman's motto of "shut-up and calculate" is a way of saying, "if you can't put a number on it, don't waste time worrying about it". Conscious minds are not a problem for empirical physicists, because Thoughts can't be dissected physically or defined numerically. Hence, they might agree with Dennett that Consciousness is not Real. Which is a truism, because it's Ideal.I don't think so. Maybe for philosophical materialists the 'problem of consciousness' is intractably "hard" but not for methodological materialists (e.g. neuroscientists, cognitive psychologists, et al) as I point out here:

https://thephilosophyforum.com/discussion/comment/511358. — 180 Proof

Ironically, in the linked thread, you concluded : " I just can't take serious mysterians like Chalmers (or other panpsychists) who propose that the 'explanatory gap' is a "hard problem" for philosophy, which it is not, because philosophy itself is not (equipped to effectively engage) in the 'theoretical explanation' business." Which sounds ironic to me, because when empirical scientists propose "theoretical explanations" for their experimental results, they are engaging in Philosophy. They are "supposing" universal principles that are not experimentally observed, but rationally imagined. A theory, such as Darwin's is essentially a just-so story, which assumes that empirical evidence will eventually be found to support the generalized conjecture. Those who share your axioms and pre-conceptions will quickly "see" the overall implications of the theory, beyond what can be directly observed, and will fill-in-the-blanks with assumptions.

For those who think of Qualia in terms of Mental Objects (such as bits of knowledge), the "mystery" of the mind is more tractable. And the developments of Information Theory post-Shannon, provide mental tools for manipulating intangible objects. Moreover, IIT is a step toward quantifying those invisible bits & bytes of Meaning & Aboutness, so that even "methodological materialists" can shut-up and calculate. Even so, until Minds can be examined under a microscope, they will remain in the philosophical category of Meta-Physical. :cool:

Theory :

a supposition or a system of ideas intended to explain something, especially one based on general principles independent of the thing to be explained.

Suppose :

assume that something is the case on the basis of evidence or probability but without proof or certain knowledge.

___Oxford Dictionary

Philosophy may be called the "science of sciences" probably in the sense that it is, in effect, the self-awareness of the sciences and the source from which all the sciences draw their world-view and methodological principles, which in the course of centuries have been honed down into concise forms

https://www.researchgate.net/post/Is-science-a-part-of-or-separate-from-philosophy -

180 Proof

16.4kIn my understanding, explaining some physical transformation manifested as a testable mathematical model is indispensible for doing science whereas interpreting such explanatory models and what the outcomes of testing them 'imply' about some aspect of the world (and, perhaps, the human condition) is doing philosophy. Scientists are also human and often unadvisedly engage in pseudo-philosophizing; however, philosophers (usually, though not exclusively, idealists & anti-realists, non-naturalists & other woo-of-the-gapsters), who rarely if ever engage in theoretical or experimental scientific practices themselves, far too often prefer to, unadvisedly, speculate pseudo-scientifically. One thing which makes them pseudo-p/s is that they both tend to conflate explanations with interpretations (e.g. the "Copenhagen Interpretation of QM" by scientists and the "Hard Problem of Consciousness" by philosophers, respectively), which can be, in effect, mutually reinforcing confusions.

180 Proof

16.4kIn my understanding, explaining some physical transformation manifested as a testable mathematical model is indispensible for doing science whereas interpreting such explanatory models and what the outcomes of testing them 'imply' about some aspect of the world (and, perhaps, the human condition) is doing philosophy. Scientists are also human and often unadvisedly engage in pseudo-philosophizing; however, philosophers (usually, though not exclusively, idealists & anti-realists, non-naturalists & other woo-of-the-gapsters), who rarely if ever engage in theoretical or experimental scientific practices themselves, far too often prefer to, unadvisedly, speculate pseudo-scientifically. One thing which makes them pseudo-p/s is that they both tend to conflate explanations with interpretations (e.g. the "Copenhagen Interpretation of QM" by scientists and the "Hard Problem of Consciousness" by philosophers, respectively), which can be, in effect, mutually reinforcing confusions. -

Wayfarer

26.2kWhich sounds ironic to me, because when empirical scientists propose "theoretical explanations" for their experimental results, they are engaging in Philosophy. — Gnomon

Wayfarer

26.2kWhich sounds ironic to me, because when empirical scientists propose "theoretical explanations" for their experimental results, they are engaging in Philosophy. — Gnomon

My thoughts exactly. Mainstream culture has drawn conclusions from the supposed 'discoveries of science', such as that the Universe is the product of physical forces, which have considerable philosophical and social ramifications.

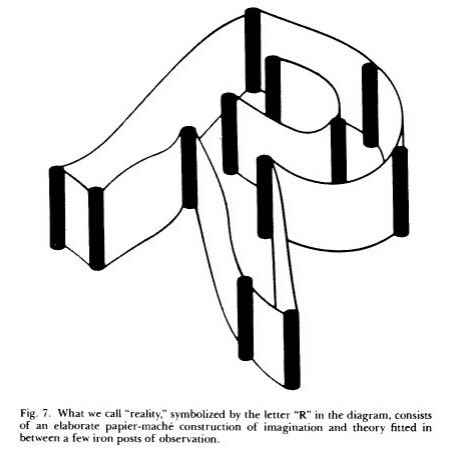

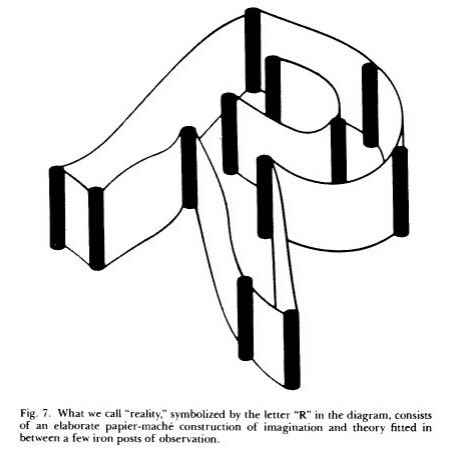

There's a graphic from a paper on the interpretation of physics which illustrates this point.

For those who think of Qualia in terms of Mental Objects (such as bits of knowledge), the "mystery" of the mind is more tractable. — Gnomon

Notice the link between 'qualia' and 'qualitative'. Why is that significant? Because of the objective sciences exclusive concentration on the quantitative and the measurable as the sole criteria for what ought to be considered real. This is what underlies David Hume's recognition of the is/ought problem. In my view, the attempt to 'solve' the hard problem, only denotes a failure to recognise what kind of problem it is. Or perhaps what is happening is that the response to the hard problem is actually producing a kind of paradigmatic shift in the way the question is being asked - it's not resolvable in the context of the scientific stance that existed at the time it was written, but scientific attitudes have shifted as a consequence (just watching CTT interview with Chalmers.)

//ps// he still (2014) says it hasn't been 'solved'.// -

Wayfarer

26.2kI had the understanding that quantum physics had obliged science to allow for the role of the observer in the conducting of experiments - the 'observer problem'. That that is one of the factors that has started to blur the boundary between object and subject which had not been noticed prior to the 1920's and the Solvay Conferences where the uncertainty principle and its implications were first discussed.

Wayfarer

26.2kI had the understanding that quantum physics had obliged science to allow for the role of the observer in the conducting of experiments - the 'observer problem'. That that is one of the factors that has started to blur the boundary between object and subject which had not been noticed prior to the 1920's and the Solvay Conferences where the uncertainty principle and its implications were first discussed.

Whereas, what is at stake in the debate over the hard problem of consciousness, is that the nature of consciousness (I prefer 'mind') is a hard problem because consciousness has an unavoidably subjective dimension. That is what is expressed in saying 'what it is like to be...' in David Chalmer's original paper on the subject.

Daniel Dennett, who is the invisible antagonist in that argument, believes that everything about the mind (soul, self, person, consciousness) can be fully explicated, in principle if not yet in practice, in objective terms. So he's denying the reality of first-person experience, or rather asserting that it's apparent reality is simply the effect of millions of automatic cellular processes that operate to create the illusion of first-person consciousness. Never mind that such an effect can only be considered illusory, if there is a subject who is mis-intepreting it; Dennett's views are riddled with such contradictions.

According to Dennett... the reality is that the representations that underlie human behavior are found in neural structures of which we know very little. And the same is true of the similar conception we have of our own minds. That conception does not capture an inner reality, but has arisen as a consequence of our need to communicate to others in rough and graspable fashion our various competencies and dispositions (and also, sometimes, to conceal them):

'Curiously, then, our first-person point of view of our own minds is not so different from our second-person point of view of others’ minds: we don’t see, or hear, or feel, the complicated neural machinery churning away in our brains but have to settle for an interpreted, digested version, a user-illusion that is so familiar to us that we take it not just for reality but also for the most indubitable and intimately known reality of all.

The trouble is that Dennett concludes not only that there is much more behind our behavioral competencies than is revealed to the first-person point of view—which is certainly true—but that nothing whatever is revealed to the first-person point of view but a “version” of the neural machinery. In other words, when I look at the American flag, it may seem to me that there are red stripes in my subjective visual field, but that is an illusion: the only reality, of which this is “an interpreted, digested version,” is that a physical process I can’t describe is going on in my visual cortex.

I am reminded of the Marx Brothers line: “Who are you going to believe, me or your own eyes?” Dennett asks us to turn our backs on what is glaringly obvious—that in consciousness we are immediately aware of real subjective experiences of color, flavor, sound, touch, etc. that cannot be fully described in neural terms even though they have a neural cause (or perhaps have neural as well as experiential aspects). And he asks us to do this because the reality of such phenomena is incompatible with the scientific materialism that in his view sets the outer bounds of reality. He is, in Aristotle’s words, “maintaining a thesis at all costs.” — Thomas Nagel, Is Consciousness an Illusion?

All you have to do to deny the hard problem, is agree with Dennett that it's an illusion - something I'm not prepared to do. -

Janus

18kI'd say Nagel's got Dennett all wrong. Dennett doesn't deny that we are immediately aware of experiences of colour.(I left out the 'real' and the 'subjective' because such experiences are real by definition just on account of the fact that we have them, and subjective by definition just on account of the fact that we are classed as subjects which means those two qualifiers are redundant). What Dennett denies is that the ideas about those experiences of colour that we form intuitively tell us anything about the real nature of consciousness, any more than they tell us anything about the real nature of colour. Of course that is not to say that we don't know the nature of our experiences of colour, because the real nature of our experiences of colour is just our experiences of colour.

Janus

18kI'd say Nagel's got Dennett all wrong. Dennett doesn't deny that we are immediately aware of experiences of colour.(I left out the 'real' and the 'subjective' because such experiences are real by definition just on account of the fact that we have them, and subjective by definition just on account of the fact that we are classed as subjects which means those two qualifiers are redundant). What Dennett denies is that the ideas about those experiences of colour that we form intuitively tell us anything about the real nature of consciousness, any more than they tell us anything about the real nature of colour. Of course that is not to say that we don't know the nature of our experiences of colour, because the real nature of our experiences of colour is just our experiences of colour.

Hence, they might agree with Dennett that Consciousness is not Real. Which is a truism, because it's Ideal. — Gnomon

That is a common misunderstanding of Dennett by his critics who apparently haven't even bothered to read his works. He doesn't deny that it's real, he just says that it isn't what we folksily think it is. If you say consciousness is not real then you are actually committing the very error you mistakenly attribute to Dennett. What could it mean to say it is ideal other than that it is merely an idea? -

Wayfarer

26.2kNagel's review of Dennett's Bacteria to Bach and Back is called 'Is Consciousness an Illusion?' David Bentley Hart's review in The New Atlantis is called 'The Illusionist'. And why? Because Dennett absolutely does assert that the first-person sense of being conscious is an illusion, created by the 'unconscious competence' of billions of interacting cellular mechanisms. You don't have to read much of Dennett to understand that, because it's the only thing he's ever said. Where Dennett has performed a great service is in showing how self-contradictory materialist philosophy of mind must be.

Wayfarer

26.2kNagel's review of Dennett's Bacteria to Bach and Back is called 'Is Consciousness an Illusion?' David Bentley Hart's review in The New Atlantis is called 'The Illusionist'. And why? Because Dennett absolutely does assert that the first-person sense of being conscious is an illusion, created by the 'unconscious competence' of billions of interacting cellular mechanisms. You don't have to read much of Dennett to understand that, because it's the only thing he's ever said. Where Dennett has performed a great service is in showing how self-contradictory materialist philosophy of mind must be. -

Janus

18kYou obviously haven't read Dennett because that is not what he says at all. How could our sense of being conscious be an illusion if we actually have a sense of being conscious? It is what we think that sense of being conscious tells us about the nature of consciousness that Dennett says is illusory. It's a subtle, but important distinction.

Janus

18kYou obviously haven't read Dennett because that is not what he says at all. How could our sense of being conscious be an illusion if we actually have a sense of being conscious? It is what we think that sense of being conscious tells us about the nature of consciousness that Dennett says is illusory. It's a subtle, but important distinction. -

theRiddler

260In order to explain consciousness, which seems to require Time in which to exist, one must explain Time itself.

theRiddler

260In order to explain consciousness, which seems to require Time in which to exist, one must explain Time itself.

It isn't enough even to find that neuron by which it is activated/deactivated. -

Janus

18kYou always run away when you are presented with good arguments against your position. I have actually read Dennett's Consciousness Explained, have you? I'm not saying that I agree with all of Dennett's conclusions either, but I don't like seeing would-be critics accuse him of claiming what he doesn't claim; particularly when it is obvious they haven't even bothered to read him; it's intellectually dishonest.

Janus

18kYou always run away when you are presented with good arguments against your position. I have actually read Dennett's Consciousness Explained, have you? I'm not saying that I agree with all of Dennett's conclusions either, but I don't like seeing would-be critics accuse him of claiming what he doesn't claim; particularly when it is obvious they haven't even bothered to read him; it's intellectually dishonest.

The so-called "Hard Problem" exists because we can't imagine how what we intuitively take consciousness to be could evolve out of what we intuitively take matter to be. If either or both of those intuitions are mistaken then the problem itself is an illusion, or to put it another way it is more a problem of the limitations of what we are able to imagine than anything else.. -

Wayfarer

26.2kAll I've asked is for you to quote some text from Dennett himself that says what you claim he says. — Janus

Wayfarer

26.2kAll I've asked is for you to quote some text from Dennett himself that says what you claim he says. — Janus

Dennett, in one of his characteristic remarks, assures us that “through the microscope of molecular biology, we get to witness the birth of agency, in the first macromolecules that have enough complexity to ‘do things.’ … There is something alien and vaguely repellent about the quasi-agency we discover at this level — all that purposive hustle and bustle, and yet there’s nobody home.” Then, after describing a marvelous bit of highly organized and seemingly meaningful biological activity, he concludes:

Love it or hate it, phenomena like this exhibit the heart of the power of the Darwinian idea. An impersonal, unreflective, robotic, mindless little scrap of molecular machinery is the ultimate basis of all the agency, and hence meaning, and hence consciousness, in the universe.

From: Daniel Dennett, Darwin’s Dangerous Idea: Evolution and the Meanings of Life (New York: Simon and Schuster, 1995), 202-3. — Steve Talbott, Evolution and the Illusion of Randomness

That is it. It is his whole philosophical approach in a nutshell, everything else comes from that. The 'acid' of 'Darwin's dangerous idea' eats through everything - philosophy included. -

Janus

18kLove it or hate it, phenomena like this exhibit the heart of the power of the Darwinian idea. An impersonal, unreflective, robotic, mindless little scrap of molecular machinery is the ultimate basis of all the agency, and hence meaning, and hence consciousness, in the universe. — Steve Talbott, Evolution and the Illusion of Randomness

Janus

18kLove it or hate it, phenomena like this exhibit the heart of the power of the Darwinian idea. An impersonal, unreflective, robotic, mindless little scrap of molecular machinery is the ultimate basis of all the agency, and hence meaning, and hence consciousness, in the universe. — Steve Talbott, Evolution and the Illusion of Randomness

He says there that the basis of consciousness is material, he doesn't say it is an illusion, You're making my argument for me; his claim is that our intuitive or "folk" notion of consciousness, that it is not materially generated and based is an illusion, he's not saying that consciousness itself is an illusion. That's the subtle, but important, distinction I referred to earlier; if you don't get that then you will be misunderstanding Dennett as Nagel apparently does.It seems surprising that Nagel would misunderstand him; which makes me think it is perhaps a wilful misunderstanding that affords Nagel a good sensationalist target that he can then seek to refute in a (he might hope) best-selling book.

Welcome to The Philosophy Forum!

Get involved in philosophical discussions about knowledge, truth, language, consciousness, science, politics, religion, logic and mathematics, art, history, and lots more. No ads, no clutter, and very little agreement — just fascinating conversations.

Categories

- Guest category

- Phil. Writing Challenge - June 2025

- The Lounge

- General Philosophy

- Metaphysics & Epistemology

- Philosophy of Mind

- Ethics

- Political Philosophy

- Philosophy of Art

- Logic & Philosophy of Mathematics

- Philosophy of Religion

- Philosophy of Science

- Philosophy of Language

- Interesting Stuff

- Politics and Current Affairs

- Humanities and Social Sciences

- Science and Technology

- Non-English Discussion

- German Discussion

- Spanish Discussion

- Learning Centre

- Resources

- Books and Papers

- Reading groups

- Questions

- Guest Speakers

- David Pearce

- Massimo Pigliucci

- Debates

- Debate Proposals

- Debate Discussion

- Feedback

- Article submissions

- About TPF

- Help

More Discussions

- Other sites we like

- Social media

- Terms of Service

- Sign In

- Created with PlushForums

- © 2026 The Philosophy Forum