-

Brian A

25The following argument seems to be a convincing argument for holding that it is more probable that God exists than that God does not exist. The argument derives from my understanding after reading Aquinas and listening to some secondary Christian resources. Is there something flawed in it?

Brian A

25The following argument seems to be a convincing argument for holding that it is more probable that God exists than that God does not exist. The argument derives from my understanding after reading Aquinas and listening to some secondary Christian resources. Is there something flawed in it?

Premise-1: Everything in the world has a cause.

Premise-2: If we trace the causes back, we arrive at the big bang, and the cause of the big bang.

Premise-3: Even if God was not the cause of the big-bang, and something natural was, still, it is very improbable that there is an infinite chain of causes going back forever.

Conclusion: Therefore, it is very probable that a non-contingent first cause exists; and this must be God, since there is nothing greater than the non-contingent first cause.

I appreciate your criticism. Thanks. -

TheMadFool

13.8kInfinity is crucial to the argument. I've always wondered why.

There are two kinds of infinity:

1. Spatial

2. Temporal

1 is not a problem. Infinite space neither helps nor hinders the argument.

2 is problematic. If there's an infinite chain of causation then the past would be infinite. The universe is travelling along a timeline and if the past were infinite, how did the universe traverse infinity to reach this point in time? Impossible.

Therefore, the chain of causation can't be infinite. We need a beginning. God is defined as this beginning of the chain of causation.

That's the crux of the argument in my view.

Anyway, the problem with this argument is that it doesn't prove the omnipotency, omnibenevolence, and omniscience of God (O-O-O God)That's an issue because the Abrahamic God is the O-O-O God.

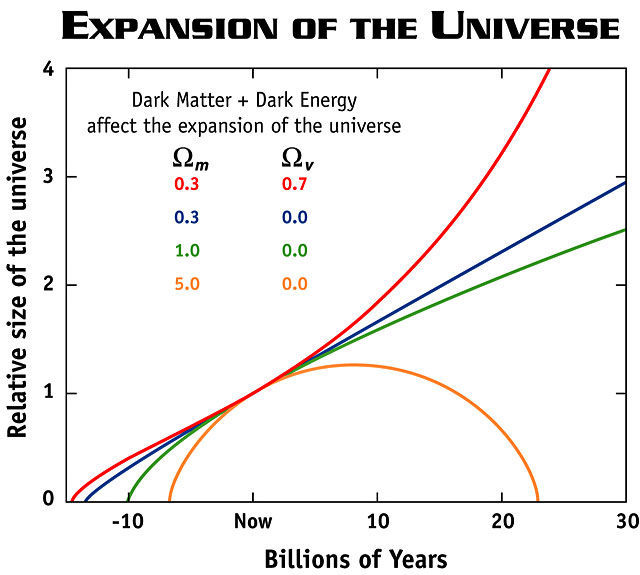

Also, we can counter the argument by positing a cyclical universe. The beginning causes the end and the end causes the beginning (circular). We get rid of the infinity problem and God isn't needed. If you look at nature, this view isn't that outlandish - water cycle, the elliptical orbits of planets, nitrogen cycle, etc. -

Brian A

25

Brian A

25

Therefore, the chain of causation can't be infinite.

I don't understand your argument about why the causal chain cannot be infinite. I don't know what you mean by the universe "traversing" the infinite. Could you explain a bit further?

Also, we can counter the argument by positing a cyclical universe.

I am hesitant to agree that this is an adequate counter-argument. For, the cyclical universe theory entails the view that there is X-amount of matter that cyclically explodes and implodes, and that matter is eternal. But it is improbable that matter is eternal; rather, it is more probable that the evolving-devolving-matter itself had a cause: viz. why something exists rather than nothing.

Anyway, the problem with this argument is that it doesn't prove the omnipotency, omnibenevolence, and omniscience of God (O-O-O God)That's an issue because the Abrahamic God is the O-O-O God.

I agree. How is one to hold the view of the O-O-O God then? My guess is that the O-O-O view arises from the ontological argument and the argument-from-design: that the mere thought of an O-O-O God in our minds indicates that such a being really exists, and that the immensity, orderliness, and goodness perceived in the universe reflects an O-O-O God, respectively. Or are there other ways to affirm an O-O-O God? -

Mr Bee

735

Mr Bee

735

I'm having trouble reading your argument, since I don't see how your premises are all related to one

another (in the sense that they all should point to a single conclusion). Most of them seem to make unjustified assumptions about the world, and others seem to outright contradict each other if not the whole conclusion of the argument (with one of them being just a statement about the conclusion itself).

Premise-1: Everything in the world has a cause. — Brian A

Wait, wasn't your argument that an infinite chain of causation was impossible? That seems to be your conclusion, but apparently one of your premises assumes that the conclusion is false. If you're trying to prove that it is false by way of a reductio, then I do not see where that comes into play.

On top of that it may not necessarily be the case that the premise is true anyways. This premise assumes determinism but it is not clear that determinism is true.

Premise-2: If we trace the causes back, we arrive at the big bang, and the cause of the big bang. — Brian A

Willing to grant that current cosmological theories suggest that there was a big bang in the earliest moments of the universe that we know of, but the idea that there was a cause to the big bang is debatable. Some physicists have suggested that there is no meaning to a "time before the big bang" and therefore no meaning to a cause of the big bang.

Premise-3: Even if God was not the cause of the big-bang, and something natural was, still, it is very improbable that there is an infinite chain of causes going back forever. — Brian A

This is a bald assertion that basically states the conclusion you want to prove. Why is it improbable that there cannot be an infinite chain of causes? That is what your argument is trying to make the case for.

So on the one hand you have a premise that assumes that everything has a cause, and in another you have a premise that basically states that an infinite chain of causes is improbable, and your conclusion is that an infinite chain of causes is impossible.

Conclusion: Therefore, it is very probable that a non-contingent first cause exists; and this must be God, since there is nothing greater than the non-contingent first cause. — Brian A

Your conclusion makes other statements that might as well be additional premises: that there must exist a first cause, that it must be a non-contingent first cause, and that that cause must be God. Like the other premises, I think you need to offer some more supporting reasons for these statements as well. -

TheMadFool

13.8kI don't understand your argument about why the causal chain cannot be infinite. I don't know what you mean by the universe "traversing" the infinite. Could you explain a bit further? — Brian A

Let me give you an analogy.

It isn't possible to reach the end of an infinite line because infinite literally means ''without end''.

Say you're at a certain point on that line and now are contemplating the nature of your beginning. Is there a starting point where you began or is it infinity on both sides from the point where you're at?

If there's a beginning there's no problem. However, if you think that it's infinity on both sides of the point you're at there's a problem viz. how did you travel an infinite distance to reach the point you're at? It's impossible to travel an infinite distance and yet there you are at a particular point on the line.

Same reasoning applies to time. If the past is infinite how did you reach the present?

The causal chain if left unchecked suffers the same setback - the infinite regress. How did an infinite chain of causes ever ocur? Infinity can't have ocurred, passed or travelled by definition. -

TheMadFool

13.8kI am hesitant to agree that this is an adequate counter-argument. For, the cyclical universe theory entails the view that there is X-amount of matter that cyclically explodes and implodes, and that matter is eternal. But it is improbable that matter is eternal; rather, it is more probable that the evolving-devolving-matter itself had a cause: viz. why something exists rather than nothing — Brian A

I only posit it to solve the infinite regress problem of the cosmological argument. I'd also like to add to the issue @Mr Bee raised.

1. Everything has a cause

2. If everything has a cause then there'a an infinite regress of causes

3. Infinite regress of causes is impossible

So,

4. It's false that everything has a cause

As you can see, 4 doesn't need us to entertain a God as an uncaused cause. Why not just conclude the universe as the uncaused cause. -

unenlightened

10kThe notion of cause requires time, because cause has to precede effect. It follows (as effect follows cause, or as conclusion follows argument?) that if there is a beginning of time, there can be no cause of that beginning in sense in which 'cause' is understood in every other case. And if there is no beginning of time, there are the problems mentioned above.

unenlightened

10kThe notion of cause requires time, because cause has to precede effect. It follows (as effect follows cause, or as conclusion follows argument?) that if there is a beginning of time, there can be no cause of that beginning in sense in which 'cause' is understood in every other case. And if there is no beginning of time, there are the problems mentioned above.

It is, in short, unthinkable that there either is or is not a beginning to time. This is because thought is time. Fortunately, it is not necessary to encompass the world with thought. -

Cavacava

2.4k

Premise-1: Everything in the world has a cause.

The assumption then is that "the world"/nature/universe is uniform everywhere and will remain so into the future. Causes are only known by induction, they are not deductive, they are only contingently possible or probable. -

Brian A

25

Brian A

25

I see that my argument was ill-constructed. Now I understand that space and time are essentially associated with the universe: that is, before the universe "banged" (presupposing the big-bang theory) there was neither space nor time. Let me re-construct my argument. It will argue that it is likely that God exists. I will assume that (a) the big-bang theory is correct, that (b) causality is real, and (c) that causality is not necessarily contingent on time (when considering a cause of the universe).

P1: Everything in the universe (the earth and the activities therein, all the galaxies, etc.) is contingent on the big-bang: that is, without the big-bang, none of these things could have existed.

P2: Time and space emerged at the moment of the big-bang.

P3: Before the big-bang, there was neither time nor space.

P4: It is probable that there was a reason, or a cause, for the big-bang (for, the universe is magnificent and even contains conscious human beings with remarkable minds).

P5: Said reason/cause must transcend space and time (since before the big-bang, space-time did not exist).

Conc.: This supra-spatiotemporal cause is likely to be God.

Also:

Why not just conclude the universe as the uncaused cause.

Since something cannot cause itself. Also, the universe contains conscious rational beings: this suggests that the ultimate, supra-temporal cause of the universe is conscious, too. -

Mr Bee

735

Mr Bee

735

P2: Time and space emerged at the moment of the big-bang.

P3: Before the big-bang, there was neither time nor space.

P4: It is probable that there was a reason, or a cause, for the big-bang (for, the universe is magnificent and even contains conscious human beings with remarkable minds). — Brian A

Seems like you decided to go with the idea that the big bang was the origin of time and space. That seems to create a problem with your P4. though like I said earlier, because if there is no such thing as a "time before the big bang" then how can anything stand in a relation of causality to it? Causality conceptually requires time to exist.

Also, you say that the big bang, which caused the universe must have a cause because the universe is magnificent, but wouldn't the same reasoning apply to God, which I imagine you would also say is magnificent? -

Wayfarer

26.2kI think the real point of all of these style of arguments can only be understood if you consider what is the nature of the kind of causation that is being discussed.

Wayfarer

26.2kI think the real point of all of these style of arguments can only be understood if you consider what is the nature of the kind of causation that is being discussed.

The kinds of causation that the natural sciences are concerned with always seem to me to presuppose natural regularity or lawful relationships between cause and effect. For example, the point about physics and physical laws is that the behaviour of mass and energy is predictable, otherwise, there would be no such thing as 'the laws of physics'. But why there are laws is a question of a different order to the kinds of things that can be discovered on the basis of those laws. We might know that f=ma, but why f=ma is another question altogether. It might not even be an answerable question, but I think it is a question.

In respect to the so-called 'big bang' theory, this is why there is an absolute barrier, beyond which physics cannot penetrate. At the moment of the singularity, as mentioned above, there are no laws, no time, no space, nor any of the other fundamentals on which science itself is based. Science can 'see' back to an infinitesmal fraction of a second after that moment, but it can never see the moment.

So an argument from natural theology might be: the Universe that emerges from the complete nothingness of the 'singularity' subsequently assumes a form which gives rise to matter and energy and ultimately also intelligent beings who are able to analyse just these kinds of questions. Why the Universe is such that it produces such an outcome, and doesn't simply remain as an inert mass of chaos, is the kind of question that is being asked by cosmological arguments. So it is a 'why' of a different order, to the kinds of causative explanations that are sought by scientific analysis. -

TheMadFool

13.8kSince something cannot cause itself. — Brian A

That's not part of the argument. What's essential to the cosmological argument is that there has to be an ''uncaused'' cause. That ''uncaused'' cause can be anything God, the universe itself.

If you insist that the universe has a cause then you'll have to explain why the chain of causation has to terminate with God. -

Wayfarer

26.2kMy guess is that the O-O-O view arises from the ontological argument and the argument-from-design: that the mere thought of an O-O-O God in our minds indicates that such a being really exists, and that the immensity, orderliness, and goodness perceived in the universe reflects an O-O-O God, respectively. Or are there other ways to affirm an O-O-O God? — Brian A

Wayfarer

26.2kMy guess is that the O-O-O view arises from the ontological argument and the argument-from-design: that the mere thought of an O-O-O God in our minds indicates that such a being really exists, and that the immensity, orderliness, and goodness perceived in the universe reflects an O-O-O God, respectively. Or are there other ways to affirm an O-O-O God? — Brian A

None of the traditional 'proofs of God' were ever intended as 'proofs' in the sense understood by modern or analytic philosophy. They were primarily exercises in intellectual edification; but Aquinas, for instance, never would have deployed such arguments to 'prove' that God existed. I think that like any Christian, he would insist that first you have to have faith in God; absent that, no argument can be convincing on its own merits.

There are some exceptions, however. There was a well-known case of British philosopher, Anthony Flew. who said that after being a convinced atheist most of his life, he came to the view that there must be some kind of higher intelligence, although he preferred to think of it along deist lines. -

WISDOMfromPO-MO

753— Brian A

WISDOMfromPO-MO

753— Brian A

Two points:

1.) We do not observe causation.

2.) The existence of causation is in doubt:

"It is easy to sympathise with those philosophers who have come to regard causes as, well, a lost cause. The venerable idea that everything that happens is caused to happen by other, distinct and separate, previous happenings – going right back to the First Cause, the mysterious Uncaused Cause (God or the Big Bang according to taste) that got happening to happen – has been under increasing attack for nearly quarter of a millennium. While it has fought back valiantly (mainly by re-defining itself), things are looking pretty bad for the idea of causation..." -- "Causes As (Local) Oomph"; Raymond Tallis; Philosophy Now, Issue 100

How is this "tracing back" of something that we do not observe done?

If causation does not exist--if there is no chain of causes and effects--then what other way would you describe reality? -

WISDOMfromPO-MO

753— Brian A

WISDOMfromPO-MO

753— Brian A

"At any rate, physical reality is seamless and law-governed, (possibly) unfolding over time, not a chain or network of discrete events that have somehow to be connected by causal cement. Causes, far from being a constitutive stuff of the physical world, are things we postulate to re-connect that which has been teased apart...", Tallis continues. -

jorndoe

4.2kHere are two arguments that an infinite past is logically impossible, and why they’re wrong.

jorndoe

4.2kHere are two arguments that an infinite past is logically impossible, and why they’re wrong.

Last Thursdayism:

- assumption (towards reductio ad absurdum): infinite temporal past

- let’s enumerate past days up to and including last Wednesday as: {..., t, ..., -1, 0}

- that is, there exists a bijection among those past days (including Wednesday) and the non-positive integers

- now come Thursday

- observation: {..., t, ..., -1, 0} cannot accommodate Thursday

- let’s re-enumerate the same past days but including Thursday as: {..., t, ..., -1, 0}

- that is, there exists a bijection among those past days (including Thursday) and the non-positive integers

- observation: {..., t, ..., -1, 0} can accommodate Thursday

- the two observations are contradictory, {..., t, ..., -1, 0} both cannot and can accommodate Thursday

- Conclusion: the assumption is wrong, an infinite past is impossible

Note, this argument could equally be applied to infinite causal chains, and nicely lends support to the Omphalos hypothesis (hence why I named it Last Thursdayism). Another thing to notice about the infinite set of integers: Any two numbers are separated by a number. And this number is also a member of the integers. The integers are closed under subtraction and addition. For the analogy with enumerating past days, this means any two events are separated by a number of days. Not infinite, but a particular number of (possibly fractional) days. That’s any two events. To some folk this is counter-intuitive, but, anyway, there you have it.

The first observation is incorrect. Whether or not the set can accommodate Thursday (one more day), is not dependent on one specific bijection (the first selected), rather it is dependent on the existence of some (any such) bijection. A bijection also exists among {..., t, ..., -1, 0} and {..., t, ..., -1, 0, 1}, and the integers, for that matter.

Therefore, the argument is not valid.

The unnumbered now:

- if the universe was temporally infinite, then there was no 1st moment

- if there was no 1st moment (but just some moment), then there was no 2nd moment

- if there was no 2nd moment (but just some other moment), then there was no 3rd moment

- ... and so on and so forth ...

- if there was no 2nd last moment, then there would be no now

- since now exists, we started out wrong, i.e. the universe is not temporally infinite

Seems convincing at a glance?

In short, the argument (merely) shows that, on an infinite temporal past, the now cannot have a definite, specific number, as per 1st, 2nd, 3rd, ..., now. Yet, we already knew this in case of an infinite temporal past, so, by implicitly assuming otherwise, the argument can be charged with petitio principii. That is, the latter (conclusion) is a non sequitur, and the latter two could be expressed more accurately as:

- if there was no 2nd last moment with an absolute number, then there would be no now with an absolute number

- since now exists, we started out wrong, i.e. any now does not have an absolute number

Additionally, note that 1,2,3 refer to non-indexical “absolute” moments (1st, 2nd, 3rd), but the following steps are indexical and contextual (2nd last, now), which is masked by “... and so on and so forth ...”. We already know from elsewhere (originating in linguistics) that such reasoning is problematic.

Still no proof, as some of the religious apologists propose. :-| -

Brian A

25I concede that the statement "before the big-bang" is nonsensical because time arises precisely with the big-bang. But surely one can acknowledge of a sort of causality, or more precisely, responsibility, that does not pivot in the existence of time. For instance, what is responsible for the big-bang? It seems probable that something beyond space-time is responsible for the big-bang. Like a God simpliciter. Of course, this would result merely in deism: but the view that something Transcendent is responsible for the big-bang seems so clear.

Brian A

25I concede that the statement "before the big-bang" is nonsensical because time arises precisely with the big-bang. But surely one can acknowledge of a sort of causality, or more precisely, responsibility, that does not pivot in the existence of time. For instance, what is responsible for the big-bang? It seems probable that something beyond space-time is responsible for the big-bang. Like a God simpliciter. Of course, this would result merely in deism: but the view that something Transcendent is responsible for the big-bang seems so clear.

So then, my understanding is the following: the human mind simply cannot cognize about "what happened prior to the big-bang", since (1) our minds operate under space and time, and (2) there was either space nor time before the big bang. So to believe in a God requires a leap of faith. But that leap of faith, by itself, does not contradict reason, as the issue of God cannot be adjudicated by reason.

If you have assumed causality is necessary, you have already assumed god.

This seems too good to be true. Is it true that if we assume the existence of causality in general (which, incidentally, seems to be a common-sense view), and trace it back, "God exists" is the necessary conclusion? So then, non-theists necessarily hold that causality is unreal?

Also, you say that the big bang, which caused the universe must have a cause because the universe is magnificent, but wouldn't the same reasoning apply to God, which I imagine you would also say is magnificent?

God is necessarily the first cause: "being the first cause" is analytically a predicate of the subject "God." The reason why God must be the first cause is because that is part of God's definition as it were, viz. "the first cause."

Thanks, I read the article. But the view that causation does not exist contradicts common intuition to such a degree that the view is rendered suspect. We can "trace back" easily, though I am not sure about the technical aspects of how. For instance, I exist due to the coming together of my parents, they exist for a likewise reason, the human species exists because of some original lifeforms in the ocean, the elements supporting life exist because of some exploding star, etc. The "tracing back" is obvious and convincing, in my view. It is true that if causality does not exist, my entire argument collapses. But I confidently assume that causality does exist, because such a view corresponds with experience and intuition. -

Brian A

25

Brian A

25

"Last Thursdayism" I am not smart enough to even follow or understand. I will agree that it fails. :).

The second argument, the "Unnumbered Now," seems to be Aquinas' 2nd of 5 proofs, the one on efficient causes. I agree that this argument fails. (I can follow it).

But has not modern science reached a consensus that time has a temporally finite past, namely via the big-bang? One thing I still haven't figured out for sure, is whether time can theoretically exist before the big bang: say, if a universe existed before the big bang.

Is it safe to say that reason cannot adjudicate the question whether or not a God exists? (And I mean God simpliciter, perhaps as it deism, and not interventionism or superstitions). -

WISDOMfromPO-MO

753Thanks, I read the article. But the view that causation does not exist contradicts common intuition to such a degree that the view is rendered suspect. We can "trace back" easily, though I am not sure about the technical aspects of how. For instance, I exist due to the coming together of my parents, they exist for a likewise reason, the human species exists because of some original lifeforms in the ocean, the elements supporting life exist because of some exploding star, etc. The "tracing back" is obvious and convincing, in my view. It is true that if causality does not exist, my entire argument collapses. But I confidently assume that causality does exist, because such a view corresponds with experience and intuition. — Brian A

WISDOMfromPO-MO

753Thanks, I read the article. But the view that causation does not exist contradicts common intuition to such a degree that the view is rendered suspect. We can "trace back" easily, though I am not sure about the technical aspects of how. For instance, I exist due to the coming together of my parents, they exist for a likewise reason, the human species exists because of some original lifeforms in the ocean, the elements supporting life exist because of some exploding star, etc. The "tracing back" is obvious and convincing, in my view. It is true that if causality does not exist, my entire argument collapses. But I confidently assume that causality does exist, because such a view corresponds with experience and intuition. — Brian A

You are doing what Tallis says here: "At any rate, physical reality is seamless and law-governed, (possibly) unfolding over time, not a chain or network of discrete events that have somehow to be connected by causal cement. Causes, far from being a constitutive stuff of the physical world, are things we postulate to re-connect that which has been teased apart..."

You are taking things that have been "teased apart" and injecting causation in between them.

If Hume and Tallis are right, it is all in our minds--causes are not, as Tallis puts it, "constitutive stuff of the physical world".

You started out by saying that everything in the world has a cause. But it seems that all of the evidence says that causes do not even exist.

It is going to take more than your subjective experience or anybody's intuition to rescue causes as something that really exists. It is going to take metaphysical evidence or objectively verifiable empirical evidence. -

TheMadFool

13.8kGod is necessarily the first cause: "being the first cause" is analytically a predicate of the subject "God." The reason why God must be the first cause is because that is part of God's definition as it were, viz. "the first cause." — Brian A

The Kalam argument:

1. There can't be an infinite chain of causes

So,

2. There was a first cause

I agree so far.

You then say God is defined as this first cause.

Ok but that still doesn't prove any of the other defining features of God such as omnibenevolence, omniscience and omnipotence or that he still exists (he could be dead by now). In short, your version of God is rather diminished.

Also, defining God as the first cause is rather tricksy. What I mean is the God-first cause relation isn't an equivalence as is asserted by defining God as the first cause. What I mean is:

1. If God exists then a first cause exists

2. If a first cause exists then God exists

1 seems reasonable but 2 is not. As you said, ''is the first cause'' is a predicate which means God has to, well, first exist before we can check whether the predicate applies or not. Not the other way round as you've done - finding the predicate (first cause) and inferring God's existence from it. -

WISDOMfromPO-MO

753Do any religions really say that anything causes anything, or is causation an extra-religious concept that people are projecting onto religious beliefs and ideas in order to support their theistic apologetics or agnosticism, atheism, anti-theism, etc.?

WISDOMfromPO-MO

753Do any religions really say that anything causes anything, or is causation an extra-religious concept that people are projecting onto religious beliefs and ideas in order to support their theistic apologetics or agnosticism, atheism, anti-theism, etc.? -

Brian A

25

Brian A

25

I agree with your last post: I see that the view that the cosmological argument proves the existence of God is begging the question, since a conception of God being the first cause is sort of presupposed: the argument is being constructed in order to fit this belief. In other words, a subjectively attractive belief is being dressed up with a ostensibly rationalistic exterior. And, as you said, even if God is this first cause, we cannot know much about this God from the mere fact that he is a first cause.

How did the religious philosophers come up with a omnipotent, omnipresent, and omnibenevolent God when inductive knowledge could not demonstrably indicate such a God? Could the explanation be something akin to Descartes' trademark argument (in which case, the deist's case would be bolstered), or is the explanation related to the philosophers' psychological need to postulate some grand myth?

Is there any way to rescue the cosmological argument as a reasonable indicator of God's existence (as in an omnipresent, omnipotent, and omni-benevolent God)? -

TheMadFool

13.8kHow did the religious philosophers come up with a omnipotent, omnipresent, and omnibenevolent God when inductive knowledge could not demonstrably indicate such a God? — Brian A

I don't know. I guess power, goodness and knowledge are highly valued qualities. If an entity has the power to create universes, it seems reasonable that it has unlimited power over its creation.

Following the same line of thought, this entity would surely have complete knowledge over its creation from the atomic to the cosmic.

Goodness isn't that easy to explain. There's no necessity in it. Perhaps as a human ideal that is clearly universal in terms of benefit (even plants and animals can be benefited from morality), it's reasonable to project it onto God who we expect loves his creation and has the noblest of intentions for it.

Is there any way to rescue the cosmological argument as a reasonable indicator of God's existence (as in an omnipresent, omnipotent, and omni-benevolent God)? — Brian A

We need separate arguments to prove God is omnipresent, omniscient and omnipotent. We can define him as such but there are inconsistencies associated with each property:

1. Omnibenevolence: problem of evil

2. Omnipotence: the paradox of the stone

3. Omniscience: free will - omniscience problem -

Thorongil

3.2kI concede that the statement "before the big-bang" is nonsensical because time arises precisely with the big-bang — Brian A

Thorongil

3.2kI concede that the statement "before the big-bang" is nonsensical because time arises precisely with the big-bang — Brian A

You don't know this, though. You seem to be taking certain physicists' word for it, who tend to be ignorant of philosophy, that time began with the Big Bang. The Big Bang is what's known as a singularity, which in layman's terms is code for "we don't know what we're talking about," because the laws of physics break down and we reach the limits of observation. It's more accurate to say, "based on our current measurements (which may change), we can't observe anything past about 13.7 billion years."

Consider also that you have shackled your argument to a claim that may not be made by scientists in the future. There's no reason to believe that another Einstein will not come along and fundamentally change our understanding of the physical universe, such that the Big Bang is then subsumed into an even more expansive and cogent theory, much like how the physics of Newton was subsumed into relativity theory. Who knows what could happen to the claim that time began with the Big Bang in that case. In other words, it would be like a 19th century person basing an argument for the existence of God on the notion of the ether. At the time, scientific consensus accepted its existence, but scientists in the 20th century discarded the notion, and so too would one then have to discard that theistic argument.

The best cosmological arguments don't start from mutable scientific claims but from certain basic concepts, like motion. -

Agustino

11.2k

Agustino

11.2k

Yes, and the deeper problem is that physical laws may actually change with time, but they may change so slowly that we haven't yet managed to perceive the changes. It would be like Newton's laws work on Earth because the curvature of space-time here is so small that it's basically imperceptible to us.Consider also that you have shackled your argument to a claim that may not be made by scientists in the future. There's no reason to believe that another Einstein will not come along and fundamentally change our understanding of the physical universe, such that the Big Bang is then subsumed into an even more expansive and cogent theory, much like how the physics of Newton was subsumed into relativity theory. Who knows what could happen to the claim that time began with the Big Bang in that case. In other words, it would be like a 19th century person basing an argument for the existence of God on the notion of the ether. At the time, scientific consensus accepted its existence, but scientists in the 20th century discarded the notion, and so too would one then have to discard that theistic argument. — Thorongil

So all our physical laws may work for 10,000 years say, but what is 10,000 years in the history of the universe? It is like the curvature of spacetime on Earth, negligible. What we're doing is basically projecting:

See how what we're doing with the size of the universe is merely projecting backwards and forwards based on theories and conjectures that we form about the model of our Universe (whether it's accelerating expansion, decelerating, etc.). The reality is, that those prior and future conditions could really be anything. Any mathematical function we can imagine, which passes through the points of observable history (which is a few thousand years) can account for the data. Likewise the age of our universe is the result of our projection. -

jorndoe

4.2k, as far as I can tell it just means that there's no purely logical argument either way, rather it comes down to evidence.

jorndoe

4.2k, as far as I can tell it just means that there's no purely logical argument either way, rather it comes down to evidence.

Sure, the evidence we have thus far, which Big Bang (mostly) is based on, suggests that (at least) the observable universe was significantly denser and "smaller" in the distant past, and has been expanding ever since. Supposing a non-infinite past, there are still some options. Whether or not it had a definite earliest time or not is speculation I guess.

The strongest intuitive argument against an infinite past I know of, is allegedly due to Wittgenstein:

However, completing an infinite process is not a matter of starting at a particular time that just happens to be infinitely far to the past and then stopping in the present. It’s to have always been doing something and then stopping. This point is illustrated by a possibly apocryphal story attributed to the philosopher Ludwig Wittgenstein. Imagine meeting a woman in the street who says, “Five, one, four, one, dot, three! Finally finished!” When we ask what is finished, she tells us that she just finished counting down the infinite digits of pi backward. When we ask when she started, she tells us that she never started, she has always been doing it. The point of the story seems to be that impossibility of completing such an infinite process is an illusion created by our insistence that every process has a beginning. — https://books.google.com/books?id=VXEuCgAAQBAJ&lpg=PT197&pg=PT197#v=onepage&q=%22Five,%20one,%20four,%20one,%20dot,%20three!%20Finally%20finished!%22&f=false

There is no logical or conceptual barrier to the notion of infinite past time.

In a lecture Wittgenstein told how he overheard a man saying '...5, 1, 4, 1, 3, finished'. He asked what the man had been doing.

'Reciting the digits of Pi backward' was the reply. 'When did you start?' Puzzled look. 'How could I start. That would mean beginning with the last digit, and there is no such digit. I never started. I've been counting down from all eternity'.

Strange, but not logically impossible. — http://www.philosophypathways.com/questions/answers_47.html#94

There are also counter-intuitive implications of a definite earliest time. -

Wayfarer

26.2kto believe in a God requires a leap of faith. But that leap of faith, by itself, does not contradict reason, as the issue of God cannot be adjudicated by reason. — Brian A

Wayfarer

26.2kto believe in a God requires a leap of faith. But that leap of faith, by itself, does not contradict reason, as the issue of God cannot be adjudicated by reason. — Brian A

That is mainstream Christian doctrine. Furthermore Christians would add that the Biblical narratives constitute evidence, which is why they're called 'revealed truth'.

if the universe were eternal and events are finite then everything would be over already.

Welcome to The Philosophy Forum!

Get involved in philosophical discussions about knowledge, truth, language, consciousness, science, politics, religion, logic and mathematics, art, history, and lots more. No ads, no clutter, and very little agreement — just fascinating conversations.

Categories

- Guest category

- Phil. Writing Challenge - June 2025

- The Lounge

- General Philosophy

- Metaphysics & Epistemology

- Philosophy of Mind

- Ethics

- Political Philosophy

- Philosophy of Art

- Logic & Philosophy of Mathematics

- Philosophy of Religion

- Philosophy of Science

- Philosophy of Language

- Interesting Stuff

- Politics and Current Affairs

- Humanities and Social Sciences

- Science and Technology

- Non-English Discussion

- German Discussion

- Spanish Discussion

- Learning Centre

- Resources

- Books and Papers

- Reading groups

- Questions

- Guest Speakers

- David Pearce

- Massimo Pigliucci

- Debates

- Debate Proposals

- Debate Discussion

- Feedback

- Article submissions

- About TPF

- Help

More Discussions

- Other sites we like

- Social media

- Terms of Service

- Sign In

- Created with PlushForums

- © 2026 The Philosophy Forum