-

Banno

30.6k

Banno

30.6k

Take a look at the contents of the SEP article on Metaphysics. It contains two sections:

2. The Problems of Metaphysics: the “Old” Metaphysics

2.1 Being As Such, First Causes, Unchanging Things

2.2 Categories of Being and Universals

2.3 Substance

and

3. The Problems of Metaphysics: the “New” Metaphysics

3.1 Modality

3.2 Space and Time

3.3 Persistence and Constitution

3.4 Causation, Freedom and Determinism

3.5 The Mental and Physical

3.6 Social Metaphysics

It does this becasue what metaphysics is changed somewhat dramatically with the advent of both modern physics and modal logic.

To restrict oneself to the "old" metaphysics is to do oneself an injustice. -

Gnomon

4.3k

Gnomon

4.3k

Since I'm an old fogy, defining Essences in the infinite (undefinable) context of zillions of possible (not yet real) worlds just hyperbolically complicates the concept for me. Why not just define Forms in terms of concepts, patterns & meanings (Essences) in human minds, in the only uni-verse (one world) we know anything about? {i.e. parsimony} Wouldn't plain old Aristotelian Logic suffice to deal with that narrow definition*1?There is a clear way of talking about essences, as those properties had by an object in every possible world in which it exists. We can deal with the consequences of essences using this stipulation. — Banno

As I understand it, Plato's allegory of a perfect heavenly realm of ideal Forms was not one of a zillion worlds, but merely a metaphorical comparison to the only world from which we extract Mental images from Material sensations. Aristotle brought the notion of Forms back down to Earth in his theory of Hylomorphism*2 : a combination of Ideal & Real (mind & body). And the informed ideas are those of homo sapiens on planet Earth, not on fantasy planet X007-Stellaris in a parallel world far far away.

Personally, I still don't see any need for logical complications to understand the meaning & application of Essence*3. The philosophy of Materialism seems to have been formulated*4 specifically to deny the existence of immaterial Forms & Ideas & Meanings & Metaphors & especially Souls. But, doesn't that also deny all the features (e.g. abstract reasoning) that distinguish humans from animals? :smile:

PS___ If we actually had examples from each of those hypothetical possible worlds, the preponderance of evidence would get us closer to absolute Truth. Sadly we only have one sample world to study.

*1. In philosophical discussions, "forms" and "essences" are often used interchangeably, representing the fundamental nature or defining characteristics of a thing. Specifically, "forms" are the abstract, ideal, and unchanging essences of things, while physical objects are mere imitations or participants in these forms.

https://www.google.com/search?client=firefox-b-1-d&q=form+and+essence

*2. While Aristotle also recognized the importance of form, he saw it as residing within things themselves, not as a separate realm. For Aristotle, form and matter are inseparable aspects of a thing, and the form gives the matter its specific characteristics.

https://www.google.com/search?client=firefox-b-1-d&q=forms+are+essences

*3. Essences :

This term refers to the fundamental nature or defining characteristics of a thing, which gives it its identity. In other words, the essence of a thing is what it is, what it cannot be without losing its identity.

https://www.google.com/search?client=firefox-b-1-d&q=forms+are+essences

Note --- Where is the material substance in these examples?:

# The essence of love is unselfishness.

# The essence of capitalism is competition.

# The essence of justice is fairness.

*4. To Form-ulate :

To express (an idea) in a concise or systematic way. ___Oxford dictionary

Note --- in other words, to Formulate means to use words to convey the imaginary idea of the identifying characteristics that are abstractions from what can be known via the physical senses. In this case, the imaginary idea is that Matter is the Essence of everything in all possible worlds.

-

Shawn

13.5kI've returned to this thread after a pause in philosophizing, sorry.

Shawn

13.5kI've returned to this thread after a pause in philosophizing, sorry.

Regarding treating the theory of forms as an attempt to comprehend itself as a form of reference, I would say this is a mistaken view for the following reason:

1. The Forms are a separate domain of discourse, which one is only able to grasp with understanding of mathematics. With regard to mathematics, the OP still is cogent. If one were to render the truths of mathematics in an informal language, then sure, it would be a pointless and futile way to say, "see this doesn't make sense", as the sense of the whole theory lies with apperception of the platonic forms in the domain of discourse of mathematics. The very notion of Truth, which the Forms are placed in is in the domain of discourse of mathematics, and probably nowhere else, (possibly in mathematical-physics perhaps).

SO, what are your thoughts about the ineffability of mathematics and the problematic translation of Truth rendered in mathematics, which is poorly understood as a language that can be seen in informal languages? -

Gnomon

4.3k

Gnomon

4.3k

Yes. Plato used the formal structure of geometry (e.g. triangles) to describe the Truth & Utility of immaterial Ideas relative to material Objects*1. Likewise, modern quantum physics deals with the invisible structure of matter that can only be known by means of mathematics*2. Hence, we accept the statistical wave nature of subatomic "particles" as True, even though they don't behave like ordinary matter (e.g. quantum tunneling ; two-slit experiment).1. The Forms are a separate domain of discourse, which one is only able to grasp with understanding of mathematics. — Shawn

So, Quantum Physics is a "separate domain of discourse", apart from Newtonian Physics of ordinary experience. But quantum truths are useful as tools for manipulating macro matter, only by means of Newtonian mechanics. So notional Forms & material Things work together to make a livable Real World for human animals.

Some relevant domain distinctions are Abstract vs Concrete & Relations vs Things & Ideal vs Real & Mental vs Material & Cultural vs Natural. The Forms, like Math, are logically true even though materially false. In their relevant cultural domain (psychology ; philosophy), Forms are useful tools for thinking, even though useless for manipulating matter, until trans-formed into a natural domain (physics ; science). :smile:

*1. Math is Form :

Yes, that's a key aspect of mathematics. It's considered a formal science because it deals with abstract structures and relationships, rather than directly with physical objects or the natural world. Mathematical statements are not about tangible objects, but rather about the relationships within formal systems

https://www.google.com/search?client=firefox-b-1-d&q=mathematics+is+formal+not+physical

*2. Quantum Math :

Because many of the concepts of quantum physics are difficult if not impossible for us to visualize, mathematics is essential to the field. Equations are used to describe or help predict quantum objects and phenomena in ways that are more exact than what our imaginations can conjure.

https://scienceexchange.caltech.edu/topics/quantum-science-explained/quantum-physics -

Shawn

13.5kSome relevant domain distinctions are Abstract vs Concrete & Relations vs Things & Ideal vs Real & Mental vs Material & Cultural vs Natural. The Forms, like Math, are logically true even though materially false. In their relevant cultural domain (psychology ; philosophy), Forms are useful tools for thinking, even though useless for manipulating matter, until trans-formed into a natural domain (physics ; science). — Gnomon

Shawn

13.5kSome relevant domain distinctions are Abstract vs Concrete & Relations vs Things & Ideal vs Real & Mental vs Material & Cultural vs Natural. The Forms, like Math, are logically true even though materially false. In their relevant cultural domain (psychology ; philosophy), Forms are useful tools for thinking, even though useless for manipulating matter, until trans-formed into a natural domain (physics ; science). — Gnomon

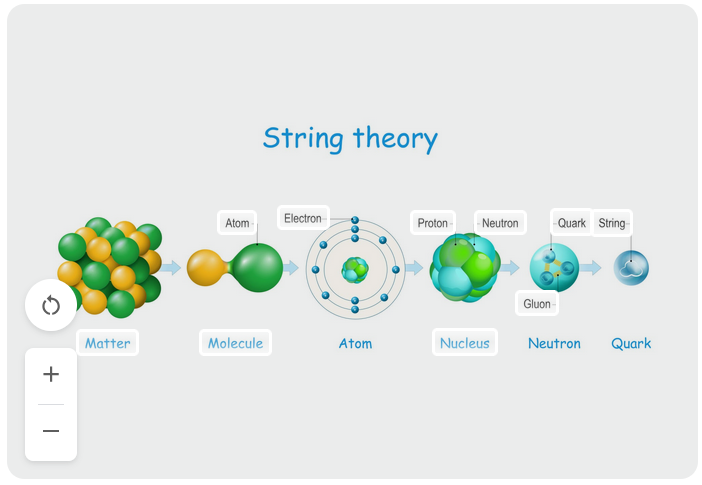

I believe that string theory is closest one can approach the Forms in terms of mathematics and physics as one would or could imagine. It's the only field in physics that is entirely dependent on mathematical relations. -

Wayfarer

26.1kSO, what are your thoughts about the ineffability of mathematics and the problematic translation of Truth rendered in mathematics, which is poorly understood as a language that can be seen in informal languages? — Shawn

Wayfarer

26.1kSO, what are your thoughts about the ineffability of mathematics and the problematic translation of Truth rendered in mathematics, which is poorly understood as a language that can be seen in informal languages? — Shawn

I think the intuition that animated the Greeks was that mathematical reasoning (Dianoia) provided an insight into a higher level of reality than did sensory perception. Even though it may be true that understanding advanced mathematics is a difficult task (one I’ve never mastered), it’s not that difficult to understand this intuition. After all, numbers never come into or go out of existence, they are not subject to change and decay as are the objects of sense, so surely, the argument has it, they are nearer the source of truth than the opinions we have about the material world. And if you consider the role that mathematics has played in science I think this basic intuition has been amply validated.

The reason that it is at odds with much of what modern philosophers think is because of the cultural impact of empiricism, which, recall, emphasises sense-experience as fundamental:

Scientists tend to be empiricists; they imagine the universe to be made up of things we can touch and taste and so on; things we can learn about through observation and experiment. The idea of something existing “outside of space and time” makes empiricists nervous: It sounds embarrassingly like the way religious believers talk about God, and God was banished from respectable scientific discourse a long time ago.

Platonism, as mathematician Brian Davies has put it, “has more in common with mystical religions than it does with modern science.” The fear is that if mathematicians give Plato an inch, he’ll take a mile. If the truth of mathematical statements can be confirmed just by thinking about them, then why not ethical problems, or even religious questions? Why bother with empiricism at all?

And from another source:

Mathematical objects are in many ways unlike ordinary physical objects such as trees and cars. We learn about ordinary objects, at least in part, by using our senses. It is not obvious that we learn about mathematical objects this way. Indeed, it is difficult to see how we could use our senses to learn about mathematical objects.

So does the distrust of Platonism really come down to the fact that Plato's 'ideas' are not things that exist in space and time, and that the only reality they could possess are conceptual? -

Gnomon

4.3k

Gnomon

4.3k

Ironically, although Strings are defined as vanishingly small --- smaller than sub-atomic particles --- they are still assumed to be material & physical, not just mathematical. The image below indicates that some physicists imagine Strings as physical things : building blocks of Quarks, which themselves present no physical evidence to support their theoretical existence.I believe that string theory is closest one can approach the Forms in terms of mathematics and physics as one would or could imagine. It's the only field in physics that is entirely dependent on mathematical relations. — Shawn

However, for all practical purposes, String Theory has been criticized as merely a plaything for extreme math aficionados. So in that sense, the String Theory may qualify for the same criticisms of Plato's hypothetical Forms : they're not Real. :smile:

PS___ Since all they do is vibrate, I would equate the mathematical strings with pure matterless Energy.

-

Wayfarer

26.1kWerner Heisenberg was a lifelong Platonist. He was known for carrying a copy of the Timeaus with him when a student, and wrote intelligently on philosophy and physics. See his The Debate between Plato and Democritus', a transcribed speech, from which:

Wayfarer

26.1kWerner Heisenberg was a lifelong Platonist. He was known for carrying a copy of the Timeaus with him when a student, and wrote intelligently on philosophy and physics. See his The Debate between Plato and Democritus', a transcribed speech, from which:

...the inherent difficulties of the materialist theory of the atom, which had become apparent even in the ancient discussions about smallest particles, have also appeared very clearly in the development of physics during the present century.

This difficulty relates to the question whether the smallest units are ordinary physical objects, whether they exist in the same way as stones or flowers. Here, the development of quantum theory some forty years ago has created a complete change in the situation. The mathematically formulated laws of quantum theory show clearly that our ordinary intuitive concepts cannot be unambiguously applied to the smallest particles. All the words or concepts we use to describe ordinary physical objects, such as position, velocity, color, size, and so on, become indefinite and problematic if we try to use them of elementary particles. I cannot enter here into the details of this problem, which has been discussed so frequently in recent years. But it is important to realize that, while the behavior of the smallest particles cannot be unambiguously described in ordinary language, the language of mathematics is still adequate for a clear-cut account of what is going on.

During the coming years, the high-energy accelerators will bring to light many further interesting details about the behavior of elementary particles. But I am inclined to think that the answer just considered to the old philosophical problems will turn out to be final. If this is so, does this answer confirm the views of Democritus or Plato?

I think that on this point modern physics has definitely decided for Plato. For the smallest units of matter are, in fact, not physical objects in the ordinary sense of the word; they are forms, structures or — in Plato's sense — Ideas, which can be unambiguously spoken of only in the language of mathematics.

I find the question of whether sub-atomic phenomena exist 'in the same way' that stones and flowers do very interesting. -

David Hubbs

9I read the first and last pages of this thread and would like to contribute. If any contributor thinks I would learn significantly more by reading some other pages before I post, please just say so. If you choose to do so, please include the relevant pages (even if its all of them) in your recommendation.

David Hubbs

9I read the first and last pages of this thread and would like to contribute. If any contributor thinks I would learn significantly more by reading some other pages before I post, please just say so. If you choose to do so, please include the relevant pages (even if its all of them) in your recommendation.

I must confess that at times, as I read, I was not sure if I was reading a rebuttal or an agreement. Sometimes the language is fairly obtuse to me. I am familiar with Platonic forms but it has been nearly fifty years since I read Plato and it’s possible I was mistaken about how well I understood it then. Today, I only loosely understand many of the posts here and have considerable uncertainty whether my ideas are relevant or appropriately expressed. If you think my post is not relevant, it’s okay to stop reading at any time and just skip/ignore this post.

In my view the Platonic forms are not dependent on physical manifestation to be real. Their existence is demonstrated/proven mathematically (at least enough for me) as an ideal that we can compare physical objects to. When concepts cannot be understood mathematically, it is difficult for me to consider them real. For example, I cannot prove mathematically or observationally that a teapot is not in orbit around Mars. I require such evidence before I would concede the teapot’s existence. I apply the same principle to string theory and multiple universes. Perhaps some physicist have proven them to their own satisfaction but they have not persuaded me. I am not suggesting that I have to be persuaded of something for it to be real, just that I have to understand the proof or have enough confidence in the claimant to accept the claim.

When Cro-Magnon hunted with spears (perhaps in groups), they understood arc and force enough to kill large animals so they could have lunch. If they failed in their effort they would either go hungry or become lunch themselves. Newton, demonstrated that arc and force could be understood mathematically (Calculus). Even though Co-Magnon did not do Calculus they understood how much force and angle to apply to be successful hunters. I call this Analog Knowledge.

I am of the camp that holds that accomplishments in mathematics are discoveries, not inventions. In other words, the mathematics to understand arc and force existed in Cro-Magnon’s time but was discovered by Newton. In this way, it is the pursuit of the ideal that allows us to calculate the behavior of objects in motion sufficiently enough to visit other bodies in space. In my view, by doing so humanity clearly demonstrated that the ideal was real. -

Gnomon

4.3k

Gnomon

4.3k

I agree. The ancient Greeks didn't have the technology to dissect real material things into their substantial elements (e.g. Atoms). So instead, they tried to analyze Reality into the Ideal/Mathematical essences of the world (e.g. Forms). We now call that "pursuit" of abstraction Philosophy. Over time though, technological inventions, such as the telescope and microscope, allowed Natural investigators to actually see what before could only be envisioned via Mathematics and imagined by Reason.In this way, it is the pursuit of the ideal that allows us to calculate the behavior of objects in motion sufficiently enough to visit other bodies in space. In my view, by doing so humanity clearly demonstrated that the ideal was real. — David Hubbs

However, I still like to maintain the distinction between scientifically Real (material, physical) and philosophically Ideal (mathematical, logical). Otherwise, our forum communication would become confusing. So, I would say that Philosophy has demonstrated that visible tangible material Reality, is fundamentally invisible essential logical Ideality. Plato's Logos & Forms were early allegories (parables?) for understanding essential unseen structures & causes of Matter & Mind. But Materialists tend to interpret those abstract metaphors literally*1.

Some modern philosophers, perhaps envying the practical successes of Physical Science, tend to interpret the world in terms of sensable/material objects (Things), instead of logical/mathematical concepts (Forms). Therefore, we need to be careful to define what Real means to each party. :smile:

*1. For example, Quarks & Strings --- as illustrated in the String Theory image above --- that can only be defined mathematically, are still imagined as geometrical lines & spheres of matter, not mind. -

Gnomon

4.3k

Gnomon

4.3k

In quantum physics today, the "smallest units of matter" (e.g. quarks, preons) are statistical probabilities rather than physical objects. Yet, the units of Statistics are data : bits of Information. And the four main types of statistical data are nominal, ordinal, discrete, and continuous. All of which are categories of mental concepts, not instances of material objects*1.I think that on this point modern physics has definitely decided for Plato. For the smallest units of matter are, in fact, not physical objects in the ordinary sense of the word; they are forms, structures or — in Plato's sense — Ideas, which can be unambiguously spoken of only in the language of mathematics.

The philosophical worldview of Atomism seems to imply that the material world is infinitely divisible into smaller components. The current title-holder of minimal matter is the hypothetical particle labeled Preon*2. Yet, they are only known to exist in the minds of theoreticians as mathematical definitions. Would Plato accept Preon in his realm of ideal Forms?

Since the foundations of modern Quantum Physics are more statistical than empirical, their primary tool today is Mathematics. Yet, practitioners seem to imagine their subject matter as Material (particles) instead of Mathematical (ratios, relationships). However, some theoretical mathematicians may admit to being Platonic Idealists*3. Which is more a matter of Faith : Materialism or Platonism? :smile:

*1. Yes, generally speaking, mathematics is considered a mental process rather than a physical one. Math deals with abstract concepts, numbers, and relationships that exist within the mind, rather than being physically tangible. While we might use physical tools like paper, pencils, or calculators to aid in calculations, the underlying mathematical principles are mental constructs.

https://www.google.com/search?client=firefox-b-1-d&q=math+is+mental+not+physical

*2. Preon models are theoretical frameworks that propose that quarks and leptons are themselves composed of smaller, more fundamental particles called preons.

Preon models arose from the desire to find a simpler, more fundamental level of building blocks, akin to the periodic table for atoms, and to address certain theoretical inconsistencies within the Standard Model.

While preon models attempt to explain certain aspects of particle physics, they lack experimental confirmation and are considered speculative.

https://www.google.com/search?client=firefox-b-1-d&q=evidence+for+preons

*3. Yes, in a philosophical sense, mathematicians are often described as idealists, particularly within the context of mathematical platonism. This view suggests that mathematical objects, like numbers and geometric shapes, exist independently of our minds and are part of a realm of ideal objects.

https://www.google.com/search?client=firefox-b-1-d&q=mathematicians+are+idealists -

Wayfarer

26.1kIt’s tempting to draw parallels between Plato’s Forms and modern physics—especially when figures like Heisenberg make explicit reference to Platonic ideas. But we should be cautious about pressing these analogies too far. The concept of Forms in Plato is not about invisible particles or mathematical abstractions per se, but about the intellect’s ability to grasp stable, intelligible principles that underlie the flux of experience.

Wayfarer

26.1kIt’s tempting to draw parallels between Plato’s Forms and modern physics—especially when figures like Heisenberg make explicit reference to Platonic ideas. But we should be cautious about pressing these analogies too far. The concept of Forms in Plato is not about invisible particles or mathematical abstractions per se, but about the intellect’s ability to grasp stable, intelligible principles that underlie the flux of experience.

This ability—what Plato would associate with the logistikon, the rational part of the soul—is foundational to reason itself. The Forms are not hypotheses about what “really exists” in some otherworldly sense, but expressions of the truth that the rational mind is oriented toward what truly is, not just to appearances. We can only recognize something as a tree, as just, as a triangle, because our minds can apprehend something universal, not merely register a bundle of sensations.

This whole conception of reason—as the faculty that “sees” the intelligible—is central to classical philosophy but has largely fallen out of favor in modern thought, due in no small part to the cultural and intellectual impact of empiricism. When knowledge is reduced to sensation and association, the idea that the mind participates in intelligible being comes to seem obscure or mystical - even if we're actually doing it every moment! And then when attention is drawn to that, we can't see it for looking.

But perhaps the real insight in Plato—and what Heisenberg may have been reaching for—is that the intelligibility of nature is not something we impose on the world, but something we discover because of the rational capacity to see what is. That’s a metaphysical claim, not a physical one, but it's crucial to any deeper understanding of what Plato's forms are supposed to mean.

Oh - and welcome to the Forum. :clap: -

Gnomon

4.3k

Gnomon

4.3k

Yes. And the Quantum physics of early 20th century seems to have required a Philosophical return to Platonic logistikon*1 (reasoning ability) after years of reliance on technological mēkhanikos*2. When subatomic particles proved to be too small for their devices to resolve, scientists were forced to resort to statistical math*3 to determine the structure & properties of unseen things. Thus, modern Physics became more Theoretical, and less Empirical. For example, Einstein & Planck didn't work in gadget-filled laboratories, but in pencil & chalk provisioned offices.The concept of Forms in Plato is not about invisible particles or mathematical abstractions per se, but about the intellect’s ability to grasp stable, intelligible principles that underlie the flux of experience. — Wayfarer

Ironically, the "seat" of Reason is sometimes referred to as a "part" of the immaterial soul, instead of a specialized function (ability) of the body/brain. I suppose thinking of Logic/Reason as-if a plug-in component is easier than imagining a non-local ghostly Form that mysteriously "grasps" other "intelligible principles".

Even more thought-provoking is the notion that fundamental particles, such as the Higgs Boson*4, are defined as local disturbances in a non-local Field of statistical potential. Underneath its invisibility cloak, the boson masquerades as inertial Mass, which is a mathematical property, not a particular thing. You could say that it is the "intelligible principle" of Gravity. Apparently, Plato took that formal essence of weightiness for granted, without comment. :smile:

*1. The logistikon is the part of the soul that deals with logic, thought, and learning.

https://www.google.com/search?client=firefox-b-1-d&q=logistikon

*2. As particles get smaller machines get larger :

The Large Hadron Collider (LHC) is considered the largest machine ever built. It's a massive particle accelerator located at CERN near Geneva, Switzerland. The LHC consists of a 27 km circular tunnel where beams of protons are accelerated to near light speed and then collided to study fundamental particles.

https://www.google.com/search?client=firefox-b-1-d&q=biggest+machine+on+earth

*3. "Subatomic math" refers to the calculations and concepts used to understand the structure and properties of atoms and their constituent particles. It involves understanding the number of protons, neutrons, and electrons in an atom, as well as the relationship between atomic number, mass number, and atomic mass.

https://www.google.com/search?client=firefox-b-1-d&q=subatomic+math

*4. God Particle :

The Higgs boson, sometimes called the Higgs particle, is an elementary particle in the Standard Model of particle physics produced by the quantum excitation of the Higgs field, one of the fields in particle physics theory. ___Wikipedia

Note --- Excitation is an exchange of Energy, which is causal potential, not material particle. But where does this mysterious incitement to Gravity come from? -

Gnomon

4.3k

Gnomon

4.3k

Philosophy Now magazine (April 2025) presents the Question of the Month : Is Morality Objective or Subjective? And one writer said "Objective moral principles are necessary to reconcile worldviews". So, it occurred to me that his theory of universal Forms might have been an attempt to objectify-by-edict ("thus saith the Lord") mandatory ethical rules that would otherwise be endlessly debatable.So does the distrust of Platonism really come down to the fact that Plato's 'ideas' are not things that exist in space and time, and that the only reality they could possess are conceptual? — Wayfarer

Yet, those imaginary abstract Forms out there in the intangible-yet-rational Aether are obviously not Empirically real. So it seems we must accept them on Plato's authority, or by agreement of our own reasoning with his. Similarly, the ancient Hebrews were presented by Moses with a compendium of ethical rules, that were supposed to be accepted as divine Laws. And violations would be punishable by real-world experiences, up to and including death & genocide. However, rather than using direct lightening bolts to punish transgressors, Yahweh used the communal belief system of his chosen people to do the job. Moses, like Plato, may have gotten his rules & principles via subjective reasoning (and historical precedent), not by divine revelation. But did P expect people to take them on faith?

Plato's Ethics*1 were based on certain moral virtues (principles) that may qualify as universal Forms. But some of Moses' Commandments, such as "Thou Shalt Not Kill" were in need of nuance. So Plato kept his Virtues general enough to apply to various situations : by interpretation from general to specific. My question is this : did Plato ever imply that his ethical rules (Forms) had something like divine authority*2 and real world enforcement? If not, then we would expect practical Morality to be subjective & disputatious, and oft-broken in deed and in principle. :smile:

*1. In Plato's ethical theory, moral virtues like justice, courage, and wisdom are considered Forms, representing the ideal and unchanging essence of these qualities. Plato believed that moral actions and character are guided by a higher realm of perfect Forms, with the Form of the Good at the apex, influencing the existence and intelligibility of all other Forms, including those of morality.

https://www.google.com/search?client=firefox-b-1-d&q=plato+morality+forms

*2. Plato believed that forms are divine. Their connection to divinity is what makes forms perfect: they lack the flaws of humans and of the physical realm. They are of a higher order of existence than their physical representations.

https://study.com/learn/lesson/plato-theory-forms-realm-physical.html

Note --- Natural "Laws" (Principles), like Gravity, can be learned by experience, and violations are immediately punished by the physical system of cause & effect. But some of the long-term evolutionary processes, such as Ecology, may take generations to see the objective results. Scientists attempt to see (infer) future states, by application of rationally-acquired general logical & mathematical rules. Perhaps Natural Morality requires more logical insight than the average person possesses. So, maybe we still need those divine edicts. -

Wayfarer

26.1kSo it seems we must accept them on Plato's authority, or by agreement of our own reasoning with his. Similarly, the ancient Hebrews were presented by Moses with a compendium of ethical rules, that were supposed to be accepted as divine Laws. And violations would be punishable by real-world experiences, up to and including death & genocide. — Gnomon

Wayfarer

26.1kSo it seems we must accept them on Plato's authority, or by agreement of our own reasoning with his. Similarly, the ancient Hebrews were presented by Moses with a compendium of ethical rules, that were supposed to be accepted as divine Laws. And violations would be punishable by real-world experiences, up to and including death & genocide. — Gnomon

Many would say that Plato and Moses were completely different historical types. After all Plato’s dialogues are meticulously rational albeit with some mythological elements. But Plato’s academy, which operated for centuries and was re-constituted in various ways over nearly a millenium, was the precursor to the modern university. Students were expected to master a comprehensive curriculum of which philosophy was only one part - there were also athletics and other subjects. In any case, rational argument and rhetoric was a major part of it, even though in other respects Platonism seems religious by today’s standards.

Moses was part of the Biblical prophetic tradition relying entirely on the truth revealed by God in the Burning Bush. And there is an inherent tension between those two traditions, one religious, the other rationalistic. (Although early in the Christian era there was a school of thought that somehow Plato had learned from or was an inheritor of the Abrahamic tradition.)

So - I wouldn’t at all agree with this ‘similarly’. -

Wayfarer

26.1kPhilosophy Now magazine (April 2025) presents the Question of the Month : Is Morality Objective or Subjective? And one writer said "Objective moral principles are necessary to reconcile worldviews". So, it occurred to me that his theory of universal Forms might have been an attempt to objectify-by-edict ("thus saith the Lord") mandatory ethical rules that would otherwise be endlessly debatable. — Gnomon

Wayfarer

26.1kPhilosophy Now magazine (April 2025) presents the Question of the Month : Is Morality Objective or Subjective? And one writer said "Objective moral principles are necessary to reconcile worldviews". So, it occurred to me that his theory of universal Forms might have been an attempt to objectify-by-edict ("thus saith the Lord") mandatory ethical rules that would otherwise be endlessly debatable. — Gnomon

In a culture of revealed truth, the Commandments weren't simply 'objective' principles to be observed from a distance, nor were they subjective wishes. For the believer, they had an existential weight that transcended the subject-object divide. They weren't just rules about reality; they were constitutive of reality itself for those who lived under their sway. They were experienced as demands - on one's being, shaping identity and defining the very framework of a meaningful life.

To violate a Commandment wasn't just to break an external rule; it was to commit an act of self-alienation, a rupture with one's fundamental relationship to God and community. It was a failure of authenticity within that revealed framework, akin to what an existentialist might describe as choosing 'bad faith' – not by denying one's freedom, but by denying the profound, revealed truth that defined one's moral landscape.

While modern existentialism often grapples with a lack of pre-given meaning, it highlights the profound personal commitment required for moral choice. In a similar vein, for those living under divine revelation, the Commandments weren't just intellectual propositions; they were existential imperatives that demand commitment. It’s very hard for us to see that, as embedded as we are in the ‘Self-Other’ paradigm of modern individualism.

While Moses's revelation is of eternal commandments, Plato's noetic apprehension of the Forms (especially the Form of the Good) is more intellectual ascent. Both have a profound, transformative impact on the individual's moral and epistemological landscape, but the path to that is different. Moses's commands are given; Plato's Forms are apprehended through rigorous, self-cultivated effort.

For Plato, too, the "seeing" of the Form of the Good transcends the simple subject-object binary. The individual intellect (subject) doesn't merely observe the Form (object) from a detached distance. Instead, the intellect must become attuned to the Form, participate in its nature, and be transformed by it through participatory knowing. The boundary between knower and known is transcended in this insight. The Form of the Good isn't just "out there" to be observed; it's something that, once "seen," reorders the entire internal landscape of the individual.

This is all very much part of what used to be the Western cultural heritage of Christian Platonism. -

Gnomon

4.3k

Gnomon

4.3k

Ha! I didn't mean to equate them as "historical types", such as a messianic prophet. I imagined them as more like analogous divine intermediary types, handing down the Truth of God (Laws vs Forms) to ordinary mortals.Many would say that Plato and Moses were completely different historical types — Wayfarer

I was just using Moses as an example of a system-maker whose supposedly divine rules were accepted on the basis of his designated authority as an interpreter of divine intentions. A more modern formal system is the notion of Natural Law that is based on the authority of secular Science, not any particular person. Hence, the ultimate authority is Nature (ultimate Reality ; Pantheos) itself, and scientists are merely self-designated interpreters. Moses' system of Divine Laws was built upon the ultimate authority of God (Ideality), and Moses was simply his messenger. Likewise, Plato's system of eternal Forms was also supposed to reveal True Reality (Ideality) that was unknown by ordinary people. So the ultimate author of those Forms was not Plato, but Nature, or God, or Good*1.

Anyway, it looks like I'm forced to answer my own poorly-formed amateur philosopher query : "My question is this : did Plato ever imply that his ethical rules (Forms) had something like divine authority?" Apparently, the answer is a provisional Yes : Plato wrote the books, but implied that the ultimate author is the essential principle of Perfect Good, and Plato is his messenger*2. Just as the Demiurge is the PanEnDeistic builder (enforcer) of our imperfect world, not of Forms, but of Things. Is that a plausible comparison of religious/philosophical system-builder, acting as intermediary for the ultimate law-maker?

Autocratic human rulers have always been aware that subjective rules are hard to enforce in a mob of independent thinkers. So, most societies & civilizations, until recently, have officially claimed that their laws are actually objective, and ideally universal, instituted not by the human on the national throne, but by the supreme God on a heavenly cathedra. Even modern secular societies may play lip service to something like Kant's Categorical Imperative : an objective universal principle that applies to all people everywhere all the time.

Perhaps Plato's perfect Forms were a similar attempt to overrule the varying opinions of quibbling quarreling philosophers with a "buck stops here" set of divine opinions, defined as perfect, unchanging, eternal verities. Surely, an ideal god-mind wouldn't create a not-yet-perfect, evolving, space-time world of relative truths and real things. Hence, the necessity for a subordinate (Demiurge) to blame for screwing-up God's divine plans. 2500 years later many of us still revere Plato as the revealer of the formal structure of the good-God's more perfect realm, for us mortals to strive for and fail. Or did he just make it all up from bits of previous philosophical systems, sans revelation? :smile:

PS___ This rambling notion, of how Ideal Forms were disclosed to humans as a supernatural system, still seems garbled, so I'll blame its imperfections on the semi-divine Demiurge we call material Evolution.

*1. In Plato's philosophy, the term "God" can be understood in a few different ways. Plato believed in a single, transcendent, and all-good being, which he often referred to as the Form of the Good. He also acknowledged the existence of other, lesser gods, often associated with the Greek pantheon, and saw them as divine beings, but not on the same level as the ultimate source of all good. Plato's concept of God also involves a Demiurge, a divine artisan who shaped the universe according to the Forms.

https://www.google.com/search?client=firefox-b-1-d&q=plato%27s+god

*2. Islamic Shahada : "There is no God but God, and Muhammed is his messenger"

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Shahada -

David Hubbs

9The distinction between logical reality and physical reality is an important one. Although humanity is not done, we recognize today that more of our view of physical reality is consistent with logical reality. I am hopeful that someday we will discover more laws of nature and not fall into the abyss of superstition. As Richard Feynman said, “I would rather have questions that can”t be answered than answers that can’t be questioned.”

David Hubbs

9The distinction between logical reality and physical reality is an important one. Although humanity is not done, we recognize today that more of our view of physical reality is consistent with logical reality. I am hopeful that someday we will discover more laws of nature and not fall into the abyss of superstition. As Richard Feynman said, “I would rather have questions that can”t be answered than answers that can’t be questioned.”

...the ancient Hebrews were presented by Moses with a compendium of ethical rules, that were supposed to be accepted as divine Laws. And violations would be punishable by real-world experiences, up to and including death & genocide. — Gnomon

If I jumped off a building I would splatter on the street as a result of gravity, not as punishment by an omniscient entity for believing I could fly. Elbert Hubbard said, “We are punished by our sins, not for them.”

Plato’s dialogues are meticulously rational albeit with some mythological elements. — Wayfarer

In Plato’s era belief in the Gods was assumed. It was normal. Although he teetered on the edge of normalcy I like to think he knew better than to alienate/insult his audience nonchalantly. -

Gnomon

4.3k

Gnomon

4.3k

What I'm still struggling with is the Subjective vs Objective nature of the Forms. Sure, Plato assures us that there is an ideal Concept, Pattern, Design of everything, but not in the Real world, so why should we believe him? As a professional designer myself, I like the idea that there is a perfect house for this couple, for example. But I've never even come close.While Moses's revelation is of eternal commandments, Plato's noetic apprehension of the Forms (especially the Form of the Good) is more intellectual ascent. — Wayfarer

Kant reasoned his way to the Categorical Imperative of morality, and others generalized the Golden Rule. But Plato implies that there is a perfect universal Form, on a shelf in the heavenly treasury, corresponding to every thing and every idea in our imperfect world*1. Carried to an extreme, presumably, there is a perfect Pickle, that is not subject to personal taste. Ideal Perfection is a nice idea, but is it true in any verifiable sense? Why should we "intellectually assent" to his noetic notion of The Good? Was Good/God a poor designer, or is there a good reason for the sorry state of our local world, after 14B years of development?

I suppose the reason I'm quibbling is because an atheist or materialist would deny that anything is perfect in our randomized accidental world. Karl Marx wanted to make the material world better, but did he envision a perfect Utopia? Why is perfection always unattainable? Why is Reality so screwed up? Why did God/Good create an inferior world of shoddy things, and keep the quality stuff for himself in Form Heaven? I'm talking like an a-form-ist here, so I can learn to answer such skeptical questions.

Back to Objectivity, would any two people agree on what constitutes an Ideal Dog? Or an ideal God? :wink:

*1. The Forms are not limited to geometry. According to Plato, for any conceivable thing or property there is a corresponding Form, a perfect example of that thing or property. The list is almost inexhaustible. Tree, House, Mountain, Man, Woman, Ship, Cloud, Horse, Dog, Table and Chair, would all be examples of putatively independently-existing abstract perfect Ideas.

https://philosophynow.org/issues/90/Plato_A_Theory_of_Forms

*2. Moral & Mathematical Forms :

"So I believe that morality is something that's discovered, in the same manner that pure mathematics discovers universal truth : it's not within us but out there."

Philosophy Now magazine p64 (April 2025) -

Gnomon

4.3k

Gnomon

4.3k

Yes. I'm sure you are not used to thinking of Forms in such irreverent terms. But my ignorant subjective/objective question about ideal Forms vs real Things, is "which is the caricature, and which is the original"? Did Plato discover the Forms, or did he invent them? It's just a rhetorical thought, no need to answer. :wink:Your depiction of the forms is something of a caricature. All I can say is, do more readings. — Wayfarer

PS___ Did Moses discover God's (formerly concealed) ideal laws on the mountain, or did he invent them? It's a question about authorship. :joke:

Plato's "Forms" are not discovered in the sense of being found by exploration. Instead, they are understood through a process of philosophical reasoning, particularly through dialectical reasoning (questioning and discussion). Plato believed that the Forms are eternal, unchanging, and the ultimate reality, and our understanding of them is a matter of recollection or intuitive grasp, not empirical discovery.

https://www.google.com/search?client=firefox-b-1-d&q=plato+forms+discovered -

Wayfarer

26.1kPlato’s so-called ‘Forms’ might be better understood as principles of intelligibility —not ghostly objects in another realm, but the structural grounds that make anything knowable or what it is. To know something is to grasp its principle, to see what makes it what it is.

Wayfarer

26.1kPlato’s so-called ‘Forms’ might be better understood as principles of intelligibility —not ghostly objects in another realm, but the structural grounds that make anything knowable or what it is. To know something is to grasp its principle, to see what makes it what it is.

And they’re neither objective - existing in the domain of objects - nor subjective - matters of personal predilection. That is why they manifest as universals -

Gnomon

4.3k

Gnomon

4.3k

Thanks for that insight. I hope you'll pardon me for my layman's playful use of less technical terms for discussing "spooky" invisible concepts that are only apparent to highly intelligent beings. Although Principles are of primary importance for philosophers, they may be un-intelligible to non-philosophers. I suppose that all humans have some minimal ability to broadly categorize their environment, but only a few go so far as to break it down into fundamental (essential) concepts for understanding (intellectual comprehension). For example, most people can count up to ten, but only a few can deal with infinities & differentials.↪Gnomon

Plato’s so-called ‘Forms’ might be better understood as principles of intelligibility —not ghostly objects in another realm, but the structural grounds that make anything knowable or what it is. To know something is to grasp its principle, to see what makes it what it is.

And they’re neither objective - existing in the domain of objects - nor subjective - matters of personal predilection. That is why they manifest as universals — Wayfarer

We tend to broadly categorize obvious things, and their essential forms, into either Objective (material things) or Subjective (mental experiences). But, as you implied, Universals may be an overarching third class of knowables, and yet we only know them via rational extrapolation from objective observation. They are not obvious, but must be discovered (revealed) by means of rational work.

In my own profession, engineers view "structure" in terms of invisible force relationships (e.g. gravity, wind, earthquake), while laymen think of "structure" in terms of obvious beams, columns, and bricks. Engineer's design diagrams symbolize those unseen forces with vectors (arrows), which might be called "principles of intelligibility" or symbols (ideograms ; mind pictures) that stand-in for the physical flow of forces that our senses cannot detect directly. Likewise, the Form "Justice" is symbolized by a conventional word, that allows the mind to make invisible political inter-relationships intelligible. :smile:

In philosophical discussions, intelligibility refers to what the human mind can understand, contrasting with what can be perceived by the senses. Intelligible forms, according to ancient and medieval philosophers, are the abstract concepts used for understanding, such as genera and species, as opposed to concrete objects. The intelligible realm, as conceptualized by Plato, includes mathematics, forms, first principles, and logical deduction. Kant's work also explores the relationship between the sensible and intelligible realms, and the principles governing each.

https://www.google.com/search?client=firefox-b-1-d&q=forms+principles+of+inteligibility -

Wayfarer

26.1kmost people can count up to ten, but only a few can deal with infinities & differentials. — Gnomon

Wayfarer

26.1kmost people can count up to ten, but only a few can deal with infinities & differentials. — Gnomon

But any normal human can converse in rational language, which relies on abstractions.

as you implied, Universals may be an overarching third class of knowables, and yet we only know them via rational extrapolation from objective observation. They are not obvious, but must be discovered (revealed) by means of rational work. — Gnomon

I've quoted this previously but it bears repeating:

Forms...are radically distinct, and in that sense ‘apart,’ in that they are not themselves sensible things. With our eyes we can see large things, but not largeness itself; healthy things, but not health itself. The latter, in each case, is an idea, an intelligible content, something to be apprehended by thought rather than sense, a ‘look’ not for the eyes but for the mind. This is precisely the point Plato is making when he characterizes forms as the reality of all things. “Have you ever seen any of these with your eyes?—In no way … Or by any other sense, through the body, have you grasped them? I am speaking about all things such as largeness, health, strength, and, in one word, the reality [οὐσίας, ouisia] of all other things, what each thing is” (Phd. 65d4–e1). Is there such a thing as health? Of course there is. Can you see it? Of course not. This does not mean that the forms are occult entities floating ‘somewhere else’ in ‘another world,’ a ‘Platonic heaven.’ It simply says that the intelligible identities which are the reality, the whatness, of things are not themselves physical things to be perceived by the senses, but must be grasped by reason. — Eric D Perl, Thinking Being, p28

So much of this has actually filtered through to the way we understand the world today - after all the Greek philosophers are foundational to Western culture. So to understand principles, to see why things are the way they are, is to see a 'higher reality' in the sense that it gives you a firmer grasp of reality than those who merely see particular circumstances. Indeed the scientific attitude is grounded in it, with the caveat that all of Plato's writings convey a qualitative dimension generally absent from post-Galilean science. -

Gnomon

4.3k

Gnomon

4.3k

Like Plato & Kant, due to the Materialistic bias of our language, I have been forced to borrow or invent new words (neologisms) to describe Metaphysical*1 concepts that don't make sense in Physical terms. In my Enformationism thesis, I describe those "occult entities" as Virtual or Potential things. I'm appropriating terms that scientists use to describe not-yet-real particles and incomplete electrical circuits for use as metaphors of un-real Forms. At my advanced age, I am still learning the lingo.This does not mean that the forms are occult entities floating ‘somewhere else’ in ‘another world,’ a ‘Platonic heaven.’ It simply says that the intelligible identities which are the reality, the whatness, of things are not themselves physical things to be perceived by the senses, but must be grasped by reason. — Eric D Perl, Thinking Being, p28

So much of this has actually filtered through to the way we understand the world today - after all the Greek philosophers are foundational to Western culture. So to understand principles, to see why things are the way they are, is to see a 'higher reality' in the sense that it gives you a firmer grasp of reality than those who merely see particular circumstances. Indeed the scientific attitude is grounded in it, with the caveat that all of Plato's writings convey a qualitative dimension generally absent from post-Galilean science. — Wayfarer

The physical focus of ordinary language may be why Plato & Aristotle used allegories & metaphors to convey the idea of unseen things. That's also why Jesus spoke in parables about spiritual notions. Whereas Plato spoke of a "higher reality", I coined the term Ideality*2 to convey the same idea, without confusing it with mundane Reality. You could say, metaphorically, it's a parallel dimension of Qualia, yet it exists side-by-side with the phenomenal world as noumenal notions in rational minds. Unfortunately such abstruse language makes philosophy enigmatic for those who don't speak Jargon or Klingon. :smile:

*1. Meta-physics :

Physics refers to the things we perceive with the eye of the body. Meta-physics refers to the things we conceive with the eye of the mind. Meta-physics includes the properties, and qualities, and functions that make a thing what it is. Matter is just the clay from which a thing is made. Meta-physics is the design (form, purpose); physics is the product (shape, action). The act of creation brings an ideal design into actual existence. The design concept is the “formal” cause of the thing designed.

https://blog-glossary.enformationism.info/page14.html

*2. Ideality :

In Plato’s theory of Forms, he argues that non-physical forms (or ideas) represent the most accurate or perfect reality. Those Forms are not physical things, but merely definitions or recipes of possible things. What we call Reality consists of a few actualized potentials drawn from a realm of infinite possibilities.

#. Materialists deny the existence of such immaterial ideals, but recent developments in Quantum theory have forced them to accept the concept of “virtual” particles in a mathematical “field”, that are not real, but only potential, until their unreal state is collapsed into reality by a measurement or observation. To measure is to extract meaning into a mind. [Measure, from L. Mensura, to know; from mens-, mind]

#. Some modern idealists find that quantum scenario to be intriguingly similar to Plato’s notion that ideal Forms can be realized, i.e. meaning extracted, by knowing minds. For the purposes of this blog, “Ideality” refers to an indefinite pool of potential (equivalent to a quantum field), of which physical Reality is a small part. A traditional name for that infinite fertile field is G*D.

https://blog-glossary.enformationism.info/page11.html

Welcome to The Philosophy Forum!

Get involved in philosophical discussions about knowledge, truth, language, consciousness, science, politics, religion, logic and mathematics, art, history, and lots more. No ads, no clutter, and very little agreement — just fascinating conversations.

Categories

- Guest category

- Phil. Writing Challenge - June 2025

- The Lounge

- General Philosophy

- Metaphysics & Epistemology

- Philosophy of Mind

- Ethics

- Political Philosophy

- Philosophy of Art

- Logic & Philosophy of Mathematics

- Philosophy of Religion

- Philosophy of Science

- Philosophy of Language

- Interesting Stuff

- Politics and Current Affairs

- Humanities and Social Sciences

- Science and Technology

- Non-English Discussion

- German Discussion

- Spanish Discussion

- Learning Centre

- Resources

- Books and Papers

- Reading groups

- Questions

- Guest Speakers

- David Pearce

- Massimo Pigliucci

- Debates

- Debate Proposals

- Debate Discussion

- Feedback

- Article submissions

- About TPF

- Help

More Discussions

- Plato vs Aristotle (Forms/forms)

- Buddha's Nirvana, Plato's Forms, Schopenhauer's Quietude

- Wittgenstein, Cognitive Relativism, and "Nested Forms of Life"

- Should troll farms and other forms of information warfare be protected under the First Amendment?

- An objection to the Teleological Argument: Other forms of life

- Other sites we like

- Social media

- Terms of Service

- Sign In

- Created with PlushForums

- © 2026 The Philosophy Forum