-

Wayfarer

26.1kWe can lay consciousness on the research table in our most expensive labs. — EugeneW

Wayfarer

26.1kWe can lay consciousness on the research table in our most expensive labs. — EugeneW

Can’t, actually. That is a metaphor that must fail, as you then say.

A Guardian article just popped up in my newsfeed:

For thousands of years, humans have struggled to understand consciousness. Poets have examined perceptions of reality and the ‘self’ through experimentation in language and form. Artists have long created complex physical representations of the consciousness, while the priests and philosophers of yesteryear have committed years of study to discovering the truth behind what we call ‘reality’.

Today, neuroscientists are investigating the ways in which our brains absorb information and perceive the world around us, and they’re increasingly honing in on the mechanisms of consciousness in the brain

So - question - before this ‘homing in’, did anyone ‘understand consciousness’. How about the Buddha? Might he have? Even without magnetic resonance imaging and the knowledge of neurotransmitters? -

Mww

5.4kI think you have actually laid consciousness on the table. — EugeneW

Mww

5.4kI think you have actually laid consciousness on the table. — EugeneW

Rock and a hard place: you won’t find consciousness, insofar as to so claim is reification of an abstract conception, but to say that of which the body is conscious is not to still be contained in the body, is a logical contradiction.

Physics and metaphysics share an Uber. One sits in the front, one sits in the back, they don’t talk, and they pay their own way. All they have in common is the ride. -

EugeneW

1.7kPhysics and metaphysics share an Uber. One sits in the front, one sits in the back, they don’t talk, and they pay their own way. All they have in common is the ride. — Mww

EugeneW

1.7kPhysics and metaphysics share an Uber. One sits in the front, one sits in the back, they don’t talk, and they pay their own way. All they have in common is the ride. — Mww

That's actually very close to my conception! I think we're a body between the physical world (the outer side of matter) and the inside brain world (the mental aspect). -

Mww

5.4k

Mww

5.4k

I’d agree there’s an inside and an outside, but not that “we’re a body between” them. Problem is, as always, that the physical must be responsible for the mental.....somehow. Or maybe it’s just the more parsimonious to suppose it is, otherwise, what we take for knowledge is even more suspect than it already is. -

Mww

5.4kThe mental resides in matter. Like charge in an electron. — EugeneW

Mww

5.4kThe mental resides in matter. Like charge in an electron. — EugeneW

It would seem that way, yes, as an analogy. Or some quantification of the same sort. But if charge per se, because all matter contains electrons, you must also say the mental is a property of matter generally, as charge is a property of electrons generally, which gets you into all kindsa philosophical trouble. -

Metaphysician Undercover

14.7kI’d agree there’s an inside and an outside, but not that “we’re a body between” them. — Mww

Metaphysician Undercover

14.7kI’d agree there’s an inside and an outside, but not that “we’re a body between” them. — Mww

The body is between the inside and the outside, just like the present is between the future and the past. We can claim directions "toward the inside", "toward the outside", just like we claim "toward the future" and "toward the past". But we cannot produce a dividing line, because there is a massive body where we think there should be a divisor. -

Mike Radford

8Thanks for kick this ball into the playground Kuro. You are quite right to comment on the trend towards physicalism in philosophy. It compliments the trend towards scientism,

Mike Radford

8Thanks for kick this ball into the playground Kuro. You are quite right to comment on the trend towards physicalism in philosophy. It compliments the trend towards scientism,

The problem with physicalism is that it cannot account for function. However exhaustive my physical explanation is for a hammer there is no explanation as to the function of a hammer. Within physical systems, parts may have their functions although this cannot be known until one considers the system as a whole. In the case of human behaviours such as banging in nails with a hammer, physicalist explanations are invariably insufficient. -

Mww

5.4k

Mww

5.4k

Agreed; there is a body between. I was objecting to “we’re a body”, which I take to be a misconception. A categorical error of equating the mere representation of a metaphysical object of pure reason, with a concrete spacetime reality.

————-

where we think there should be a divisor. — Metaphysician Undercover

The explanatory gap? -

Gnomon

4.3k

Gnomon

4.3k

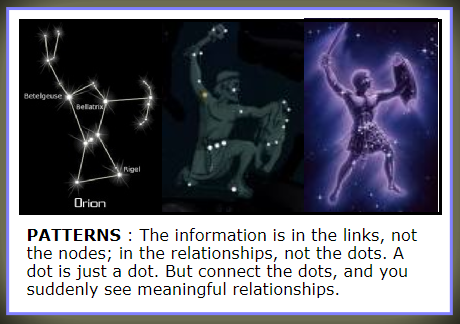

That's a new idea to me. But, in view of our discussion of the "logic of reality", I would imagine that Mathematical Logic (bonding relationships ; valence) is the structure of reality, and Mathematical Energy (ratios ; differences) is the cause of structural changes. That concept seems to be compatible with the Enformationism worldview, in which Generic Information (ratios, relationships, connections, differences) is the universal "substance" (per Spinoza) of the world.Right. To me that suggests an intrinsic connection between maths and the world. I'm interested in the idea that scientific laws exist where logical necessity meets physical causation. — Wayfarer

Just riffing on a metaphorical theme here : perhaps, the holistic Potential of the pre-BigBang Singularity (egg : zygote), after fertilization (by whom??), contained two Actual aspects : material structure (female ; mother) and dynamic causation (male : sperm). Hence, by analogy with biological development, that initial binary scenario has evolved over the intervening eons into the multiplex world of Matter & Energy we know as Reality. The role of Matter, in this myth, is the stable (Necessity) structure, and Energy is the dynamic (Chance) force of transformation, which explores all options within Possibility Space.

But, who or what defines the limits on possibility? In my myth, the original Egg was programmed by a pre-existing Planner or Lawmaker. However, Materialists might imagine that pre-BB "substance" as a fecund Multiverse (the eternal Mother ; mater). And Spiritualists would picture the dynamic virility as a powerful Elan Vital (eternal Father ; pater). However, my metaphorical myth combines the dual aspects of Reality into a singular Source of Being (cosmic creative principle : Brahman). Of course, anything prior to our local space-time is inherently unknowable. But its causal & substantial (formal) role is still inferrable, by analogy with the substance & laws of the known world. Some might even like to call it the "Great Mathematician". :nerd:

How mathematics reveals the nature of the cosmos :

Mathematics is the language of the universe, and in learning this language, you are opening yourself up the core mechanisms by which the cosmos operates.

https://phys.org/news/2015-06-mathematics-reveals-nature-cosmos.html

Generic Information :

Information is Generic in the sense of generating all forms from a formless pool of possibility : the Platonic Forms.

BothAnd Blog. post 33 -

Metaphysician Undercover

14.7kAgreed; there is a body between. I was objecting to “we’re a body”, which I take to be a misconception. A categorical error of equating the mere representation of a metaphysical object of pure reason, with a concrete spacetime reality. — Mww

Metaphysician Undercover

14.7kAgreed; there is a body between. I was objecting to “we’re a body”, which I take to be a misconception. A categorical error of equating the mere representation of a metaphysical object of pure reason, with a concrete spacetime reality. — Mww

The temporal analogy holds quite well for this idea of "we're a body", or more precisely "I'm a body" ("we're a body" contains a further problem of unity). If the body, in its existence, is like the present in time, we still have to account for the reality of the future and the past. Future and past are somehow external to the present, outside it, but are still a very real part of it as defining features. Likewise, there are very real parts (defining features) of a living being, which are somehow outside the living body.

The explanatory gap? — Mww

I believe it's a failing in our understanding of what constitutes a "boundary". Peirce had some interesting ideas on this issue, but I do not agree with his proposed resolution. Suppose there are two distinct substances in contiguity. What keeps them separate? Either we propose a third substance which acts as the boundary to separate the two, or we assume a zone of mixing. If I remember correctly, Peirce chooses the latter, a mixing, and the boundary becomes vague, because that's how such situations appear empirically, through our senses. However, I believe that removing the need for a third substance introduces an unwarranted principle of unintelligibility into the explanation. Now we have no reason why the two are separated in the first place, they are simply not completely mixed. So I think, that to provide a true explanation we must always appeal to a "third substance" as the boundary, because it is only by understanding a third thing, that the reason why the two are separated will be grasped.

This is very evident in the nature of time. as well as the human experience of internal/external. If we propose that the human experience is just a mixing of internal/external, or that the present in time is just a mixing of future and past, without assuming a third thing which is the actual reason why the two sides of these apparently dichotomous divisions exist, then these two (human experience, and the present in time) become unintelligible. Therefore we must apprehend the reality that these are not true dichotomies, because in each case there is a third thing, which acts as the boundary separating the two which only appear to our senses to be dichotomous. -

Count Timothy von Icarus

4.3k

Count Timothy von Icarus

4.3k

This is not true at all. It is generally proposed in metaphysics, and supported by evidence, that a whole is greater than the sum of its parts. There is a logical fallacy, the composition fallacy, which results from what you propose.

I was speaking to identity in that post. The words "parts and wholes" is misleading there. When we say an object has the trait of being a triangle, or that it instantiates the universal of a triangle, we aren't referring to any one of its angles, right?

The concept of emergence and the composition fallacy doesn't apply to bundle theories of identity. A "trait" is not a stand in for a part of an object. For example, traits aren't parts in the sense that a liver is a part of a human body or a retina is part of an eye.

A trait - that is a trope (nominalism) or the instantiation of a universal (realism) - applies to the emergent whole of an object. They have to do so to serve their purpose in propositions. For example, the emergent triangularity of a triangle is a trait. The slopes of the lines that compose it are not traits, they are parts (they interact with traits only insomuch as they effect the traits of the whole). The way I wrote that was misleading, but the context is the identity of indiscernibles.

Traits are what allow propositions like "the bus is red," or "the ball is round" to have truth values. The sum total of an object's traits is not the sum total of its parts. It is the sum of all the predicates that can be attached to it. So an object that is "complex" but which is composed of "simple" parts still has the trait of being complex.

So to rephrase it better, the question is "is a thing defined by the sum of all the true propositions that can be made about it, or does it have an essential thisness of being unique to it?"

And this is nothing but nonsense. What could a "substratum of 'thisness'" possibly refer to? "

Yes, that is the common rebuttal I mentioned. It sounds like absurd gobbledygook. Now, its supporters claim that all ontologies assert ontologically basic brute facts, and so this assertion is no different, but it seems mighty ad hoc to me. That this theory still has legs is more evidence of the problems competitors face than its explicit merits.

You attempt to make the description, or the model, into the thing itself. But then all the various problems with the description, or model, where the model has inadequacies, are seen as issues within the thing itself, rather than issue with the description.

This sort of "maps versus territory" question begging accusation is incredibly common on this forum. It's ironic because in the context it is normally delivered, re: mental models of real noumena versus the real noumena in itself, it is itself begging the question by assuming realism.

As a realist, I still take the objection seriously, but I'm not totally sure how it applies here.

This is not really true. Time is a constraint in thermodynamics, but thermodynamics is clearly not the ground for time, because time is an unknown feature. We cannot even adequately determine whether time is variable or constant. I think it's important to understand that the principles of thermodynamics are applicable to systems, and systems are human constructs. Attempts to apply thermodynamic principles to assumed natural systems are fraught with problems involving the definition of "system", along with attributes like "open", "closed", etc..

The "thermodynamic arrow of time," refers to entropy vis-á-vis the universe as a whole. Wouldn't this be a non-arbitrary system.

I agree with the point on systems otherwise. I don't think I understand what "time is an unknown feature," means here. Is this like the "unknown features" of machine learning?

This is a mistaken notion which I commonly see on this forum. Definition really does not require difference. Definition is a form of description, and description is based in similarity, difference is not a requirement, but a detriment because it puts uncertainty into the comparison. So claiming that definition requires difference, only enforces my argument that this is proceeding in the wrong direction, putting emphasis on the uncertainty of difference rather than the certainty of sameness. A definition which is based solely in opposition (difference), like negative is opposed to positive for example, would be completely inapplicable without qualification. But then the qualification is what is really defining the thing that the definition is being applied to.

The difference/similarity distinction is two heads of the same coin. I start with difference only because Hegel did and that's where my thinking was going.

If you start with the idea of absolute, undifferentiated being, then difference is the key to definition. If you start with the idea of pure indefinite being, a chaotic pleroma of difference, then yes, similarity is the key principal.

Hegel used both. In the illustration from sense certainty, we face a chaotic avalanche of difference in sensations. The present is marching ever forward so that any sensation connected to the "now" of the present is gone before it can be analyzed. This pure unanalyzable difference is meaningless. The similarities between the specific moments of conciousness help give birth to the analyzable world, a world of schemas, categories, and traits. However, these universals (in the generic, not realist sense) in turn shape our perception (something you see borne out in neuroscience). So the process of meaning is a circular process between specifics and universals, difference and similarity.

You cannot make definitions if all you have access too is absolute difference or absolute similarity. Similarity alone cannot make up a definition. As Sausser said, "a one word language is impossible." If one term applies to everything equally, with no distinction, it carries no meaning. In the framework of Shannon Entropy, this would be a channel of nothing but infinite ones or infinite zeros. There is zero surprise in the message.

For instance, you can define green things for a child by pointing to green things because they also see all sorts of things that aren't green. If, in some sort of insane experiment, you implant a green filter in their eyes so that all things appear to them only in shades of green, they aren't going to have a good understanding of what green is. Green for them has become synonymous with light, it has lost definition due to lack of differentiation.

The interesting thing is that this doesn't just show up in thought experiments. Denying developing mammals access to certain types of stimuli (diagonal lines for instance) will profoundly retard their ability to discriminate between basic stimuli when they are removed from the controlled environment in adulthood.

Can you explain how these folks get around the issues mentioned above though? The ones I am familiar with in this list have extremely varied views on the subject.

Nietzsche's anti-platonist passages are spread out, and I'm not sure they represent a completed system, but he would appear to fall under the more austere versions of nominalism I talked about. Like I said, these avoid the problem of the identity of indiscernibles, but at the cost of potentially jettisoning truth values for propositions.

Rorty is a prime example of the linguistic theories I mentioned. The complaint here is again about propositions. Analytical philosophers don't want to make propositions just about the truth values of verbal statements. Plus, many non-analytical philosophers still buy into realism, at least at the level of mathematics (the Quine–Putnam indispensability argument re: abstract mathematical entites have ontic status).

On a side note, I honestly find it puzzling that eliminativists tend to like Rorty. Sure, it helps their claims about how lost we are in assuming conciousness has the depth we "think," we experience, but it also makes their work just statements about linguistic statements.

I am familiar with Deleuze and to a lesser extent Heidegger on this subject. I have never seen how moving from ontological identity to ontological difference independent of a concept of identity fixes the problem of the identity of indiscernibles. It seems to me that it "solves" the problem by denying it exists.

However, it does so in a way that makes me suspicious of begging the question. Sure, difference being ontologically more primitive than identity gets you out of the jam mentioned above by allowing you to point to the numerical difference of identical objects as ontologically basic, but it's always been unclear to me how this doesn't make prepositions about the traits of an object into mere brute facts. So in this sense, it's similar to the austere nominalism I was talking about before.

Now I think Putnam might have something very different to say here vis-á-vis the multiple realizability of mental states, and what this says about the traits of objects as experienced, verses their ontological properties, but this doesn't really answer the proposition problem one way or the other. It does seem though, like it might deliver a similar blow to propositions as the linguistic models (e.g., Rorty). Propositions' truth values are now about people's experiences, which I suppose is still a step up from being just about people's words or fictions, and indeed should be fine for an idealist. -

Gnomon

4.3k

Gnomon

4.3k

I haven't read the previous posts in your dialog, but the "similarity vs difference" and "absolute undifferentiated being" rang a bell. In my personal worldview, the pre-BigBang source of our real world was what I call "BEING". I borrowed Plato's notion that real organized Cosmos emerged from ideal disorganized Chaos. But I have to distinguish the ideal concept of monolithic omnipotential Chaos -- no actual things, just potential for all things -- from the modern notion of irrational confusion & disorder. Another term for the unitary fullness of all possible things is a perfect Pleroma. But that has some specific religious references, that are not necessary for philosophical purposes.The difference/similarity distinction is two heads of the same coin. I start with difference only because Hegel did and that's where my thinking was going.

If you start with the idea of absolute, undifferentiated being, then difference is the key to definition. If you start with the idea of pure indefinite being, a chaotic pleroma of difference, then yes, similarity is the key principal. — Count Timothy von Icarus

In my usage, Chaos is "irrational" only in the sense that it is unitary & atomic, with no separate parts to rationalize or organize, and no pattern to disarray. So, BEING is "absolute & undifferentiated". It's also a Mathematical Singularity, in the sense of having no parts to define it, just pure Potential (creative power) from which all the components of our Reality are derived. Metaphorically, Chaos is like an ovum, which can split into two halves, which continue to divide & differentiate into Darwin's "endless forms most beautiful". However, since the Chaos egg is assumed to be omni-potent, our universe is just a tiny fragment of the infinite possibilities that remain undifferentiated.

Realists & Physicalists typically envision those possible un-known pre-cosmoses as a physical Multiverse, or a real array of Many Worlds. But, I prefer to avoid speculating beyond the only differentiation that we know is necessary for our temporary & contingent home world to exist. Like idealistic Plato, and using Ockham's Razor, I simplify the Beginning of Being (space-time) down to just "pure indefinite BEING" (AKA : Chaos) and alloyed differentiated things (AKA : Cosmos). So, our physical world is characterized by both Difference & Similarity, whereas BEING is Indifferent & Unitary. Hence I must agree that "If you start with the idea of pure indefinite being", then "similarity is the key principal" for defining the multiplicity of created beings & things in our world. :nerd:

BEING :

In my own theorizing there is one universal principle that subsumes all others, including Consciousness : essential Existence. Among those philosophical musings, I refer to the "unit of existence" with the absolute singular term "BEING" as contrasted with the plurality of contingent "beings" and things and properties. By BEING I mean the ultimate “ground of being”, which is simply the power to exist, and the power to create beings.

Note : Real & Ideal are modes of being. BEING, the power to exist, is the source & cause of Reality and Ideality. BEING is eternal, undivided and static, but once divided into Real/Ideal, it becomes our dynamic Reality.

BothAnd Blog Glossary

Mathematical Singularity :

In mathematics, a singularity is a point at which a given mathematical object is not defined, . . . .

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Singularity_(mathematics)

Note -- the BigBang "Singularity" is a mathematical expression of the Unitary source of our differentiated reality : the ground of our being.

MANY WORLDS OR MULTIVERSE , WHAT'S THE DIFFERENCE ?

-

Joshs

6.6k

Joshs

6.6k

I have never seen how moving from ontological identity to ontological difference independent of a concept of identity fixes the problem of the identity of indiscernibles. It seems to me that it "solves" the problem by denying it exists.

However, it does so in a way that makes me suspicious of begging the question. Sure, difference being ontologically more primitive than identity gets you out of the jam mentioned above by allowing you to point to the numerical difference of identical objects as ontologically basic, but it's always been unclear to me how this doesn't make prepositions about the traits of an object into mere brute facts. So in this sense, it's similar to the austere nominalism I was talking about before. — Count Timothy von Icarus

The numerical difference of identical objects is very far removed from the notion of difference that drives the work of authors like Derrida, Deleuze and Heidegger.

They don’t begin from identity and then add difference onto it. What is an identity? What is self-identicality? What is a logical proposition such as A=A? The concern of these writers is to show that what is assumed as an identity with attributes, traits and properties is o my so as an idealization.

Husserl wrote a book , Formal and Transcendental Logic, in which the starting point for writers like Frege and Russell , S is P, is the end product of a long and complex process of constitution. From their vantage, all that Husserl contributes was a pointless psychologistic analysis. But what he actually accomplished was the exposition of the hidden assumptions and conditions of possibility for the abstractions that Frege took as primordial . In other words , in order to have an adequate grasp of the nature of truth as it is asserted in propositions, one must recognize that the form of the proposition is a derived abstraction that takes for granted what is really at stake in determining the basis of assertions of truth. -

Bob Ross

2.6k@Kuro,

Bob Ross

2.6k@Kuro,

To briefly answer your original question, I think that most people nowadays default to materialism (physicalism). But since this discussion forum has seemingly naturally segued into an actual debate between more idealist minded individuals vs more materialistic minded individuals, let me give you my two cents (for whatever they are worth) on the topic. I think that a vast majority of what we know is empirical, but necessarily never solely such: some things are presupposed in any empirical investigation. To be clear and concise, let me provide one example: connectives (as the components of a conclusion which act as the connections, whether that be synthetic or analytic) is always necessarily presupposed in any empirical evaluation. To keep it brief, I think that reason is always met with a recursive potential infinite of connectives when attempting to empirically explain any given connective. For example, if A is connected (in any fashion or form) to B, we then can very well ask why that connective is valid. But when, let's say, explanations for the connective(s) involved in connecting A to B are derived (such as C and D or what have you), we can always ask the very same of those connectives utilized to derive such, and we can perform this for a potential infinite of times, thereby we never get any closer to explaining connectives (i.e. the actual connective's validity, for any further explanation necessarily utilizes connectives itself which are presupposed as valid in explaining the original connective); Only as we trudge along the path of the recursive potential infinite of explanations of connectives do (I think) we realize that the most cogent solution is that of connectivity being transcendental (as in not completely separate from reason--aka not transcendent--but proposed as necessarily an unconditional absolute grounding of reason itself as derived from reason), whereby we still freely concede that this was also a connection and, consequently, the connective(s) involved in that conclusion reveal connectives, as a whole, as truly something of a potential infinite prerequisite of reason itself. So, in relation to reason, it is reasoned that connectives can only be proficiently explained in reference to its potential infinite nature, which necessitates that it be conceptualized as transcendental of reason. Furthermore, this entire investigation into connectives was obtained empirically by analysis of reason on itself to determine that, actually, this entire process of empirical investigation always (for a potential infinite) presupposes the validity of all connectives. So, that which is transcendental (in this case, connectivity) is necessarily obtained empirically, but reveals that which is necessarily presupposed for empiricism in the first place (that which is not empirical). So, I hold, even if we could hypothetically explain (which involves connections) the mind as reduced to the brain, we would not have gotten any closer to explaining the connectives utilized in that empirical investigation: therefore, at best (hypothetically), the mind holistically being derived of the material brain (holistically in the sense that seemingly every manifestation of reason is properly explained by science--i.e. we could tell when you think of a car vs a cat, decide to do something, make you angry, etc) would only be in relation to reason and the connectives presupposed as valid in the first place and, consequently, only ever pertaining to what is manifested by reason and not what is transcendentally true of all manifestations of reason itself--therefore not truly holistically (as in completely) explanatory (there's always an aspect that will never to be explained).

Bob -

Metaphysician Undercover

14.7kA "trait" is not a stand in for a part of an object. For example, traits aren't parts in the sense that a liver is a part of a human body or a retina is part of an eye. — Count Timothy von Icarus

Metaphysician Undercover

14.7kA "trait" is not a stand in for a part of an object. For example, traits aren't parts in the sense that a liver is a part of a human body or a retina is part of an eye. — Count Timothy von Icarus

I don't agree with this. Concepts are composed of parts, and the parts are "traits", only in a slightly different way from the way that physical objects are composed of parts. This is because the parts which are said to make up a physical object are understood as concepts anyway. So an object has different formations of molecules, which might be referred to to separate one part of the eye from another, but this is a conceptual description. And we see this more clearly when we say a molecule consists of atoms, and atom of other parts. It's all theory. conceptual. Unless you take an object, and start physically breaking it apart, there is no basis for your claim of difference. But when you do this, the object doesn't necessarily break at the points indicated. If you cut up the eyeball the retina does not necessarily separate itself out, because this is a theoretical distinction you have made.

A trait - that is a trope (nominalism) or the instantiation of a universal (realism) - applies to the emergent whole of an object. They have to do so to serve their purpose in propositions. For example, the emergent triangularity of a triangle is a trait. The slopes of the lines that compose it are not traits, they are parts (they interact with traits only insomuch as they effect the traits of the whole). The way I wrote that was misleading, but the context is the identity of indiscernibles. — Count Timothy von Icarus

So these assumptions are not true at all. The lines and angles are traits. The line and the angle are concepts which are traits of the concept of triangle, and they are also the parts of the triangle.

So to rephrase it better, the question is "is a thing defined by the sum of all the true propositions that can be made about it, or does it have an essential thisness of being unique to it?" — Count Timothy von Icarus

Each particular thing is unique, in itself, having a thisness all to itself, but it is defined by the true propositions made about it. There is a gap between these two due to the deficiencies of the human capacities. -

Count Timothy von Icarus

4.3k

Count Timothy von Icarus

4.3k

Yeah, that's sort of where I was headed at first thinking about these things. The problem of parts being traits though is that it seems like objects reduce to fundemental particles, as in your example.

Interestingly, there are forms of realism people have proposed where the only universals/forms are the fundemental particles. I've never seen nominalism of this sort before, but I could see how it would work. Fundemental particles would be the only tropes, and tropes would really just be names for the excitations of quantum fields we observe.

These are pretty neat. The problem they might have for your stand point comes up here:

Each particular thing is unique, in itself, having a thisness all to itself,

Physicists generally claim that fundemental particles do lack haeccity. Lately though, there has been some debate as to how indiscernible particles really are. In some cases, they may not be fully indiscernible, the jury is out.

For the most part though, we are told not to assume that an electron we trapped in a box will remain the same electron when we open the box. Or, another proposed way to look at it is to say there is only one electron. The electron is not affected by time, and so it can be everywhere at once.

For a bit more detail:

French & Redhead’s proof is based on the assumption that when we consider a set of n particles of the same type, any property of the ith particle can be represented by an operator of the form Oi = I(1) ⊗ I(2) ⊗ … ⊗ O(i) ⊗ … ⊗ I(n), where O is a Hermitian operator acting on the single-particle Hilbert space ℋ. Now it is easy to prove that the expectation values of two such operators Oi and Oj calculated for symmetric and antisymmetric states are identical. Similarly, it can be proved that the probabilities of revealing any value of observables of the above type conditional upon any measurement outcome previously revealed are the same for all n particles.

The original paper.

An easier write up .

Now, keep this lack of haecceity in mind and think of how different particles might be seen to function very much like the way letters function in a text (a "T" is always a T; the specific T is meaningless, only its role in a word matters). Words are made up of letters, but words can have properties like "adjective" or "noun." Their traits don't come from their parts. Then, their role as subject or predicate in a sentence is further not derived from their letters, but by their relationship to other words.

So these assumptions are not true at all. The lines and angles are traits. The line and the angle are concepts which are traits of the concept of triangle, and they are also the parts of the triangle.

But then which letter/concept in a word holds the trait "noun?" Which parts can be summed up into the concept "noun?" This property can't just be attributed to the rules of spelling, the way the rules of geometry denote "triangle" from the slope of a triangle's three lines, because random mixes of letters can be proper nouns in fiction novels and we create new words all the time. Additionally, words have a meaning when spoken as well as written, and illiterate people can understand words without the letters that make them up.

Same holds for the trait of "predicate." It seems the traits a word posseses can't just be coming from the parts, no? In this case, a part of a sentence gets its trait from a whole that it is a part of, in the same way eyes have the trait of being organs due to being parts of whole bodies. Even if the components of words are actually "ideas," I don't know how this gets you to nouns being subjects of sentences, as in the property of the word "Jamie" in a sentence like "Jamie is a dog," which features two nouns.

[an object] it is defined by the true propositions made about it

And here is the other big problem with these fundemental systems: fundemental particles can't be triangles, they don't have a color, they can't be circles, they can't be lighter or darker than each other, they can't be translucent, etc. All these properties are emergent.

So, if traits are actually just parts, I'm not sure I see a way for propositions such as "the block Thomas picked up is triangular," can have truth values. Because the block is actually made up of atoms that aren't triangular, and if you say that the triangularity comes from the block's parts, then you are admitting that objects can have traits that their parts lack, and of course "being made of atoms" isn't necissary or sufficient as a cause of being triangular.

Arguably, the block isn't triangular. It's like Mandelbrot's map of the British coastline, which actually has infinite length because you can always measure at finer and finer detail, which will reveal ever smaller irregularities in the coast line that add to its length. So, the edge of the block is actually a roiling landscape of microscopic bumps, not a straight line.

However, this seems like a pretty big blow to propositions. You can get around this problem with Mandelbrot's insight that the same shape has a different number of dimensions when viewed from different perspectives. His example was a ball of string. From very far away, it is a one dimensional point. As you get closer, it becomes a two dimensional line of string. Get closer still, and it is a three dimensional cylindrical entity. Get closer still, to the scale of fundemental particles, and it is now a group of one dimensional points. (The insightful kicker here is that the strong has fractional dimensions at different points along this analysis).

But if you do this, you're back to looking at the traits of the object as a whole, not the parts. -

Metaphysician Undercover

14.7kInterestingly, there are forms of realism people have proposed where the only universals/forms are the fundemental particles. I've never seen nominalism of this sort before, but I could see how it would work. Fundemental particles would be the only tropes, and tropes would really just be names for the excitations of quantum fields we observe. — Count Timothy von Icarus

Metaphysician Undercover

14.7kInterestingly, there are forms of realism people have proposed where the only universals/forms are the fundemental particles. I've never seen nominalism of this sort before, but I could see how it would work. Fundemental particles would be the only tropes, and tropes would really just be names for the excitations of quantum fields we observe. — Count Timothy von Icarus

This is Platonic realism. "Fundamental particles" are nothing but mathematical equations made to represent observations. When we claim that these mathematical representations constitute the reality of what is observed, this is Platonism. I don't think this qualifies as nominalism, because nominalism would say that these equations are just our way of describing what is observed.

Physicists generally claim that fundemental particles do lack haeccity. Lately though, there has been some debate as to how indiscernible particles really are. In some cases, they may not be fully indiscernible, the jury is out. — Count Timothy von Icarus

The problem I see is with this assumption: that the observation of a particle, at one time, then a particle at another time, is the same particle. So for instance, a photon is emitted, and an equal photon is absorbed at another place, in a way which corresponds. It is assumed that these are the same particle but that is where the problem is. The continuous existence of the particle between t1 and t2 cannot be accounted for, so the claim that the two instances are instances of the same particle, is not really a valid claim.

Now, keep this lack of haecceity in mind and think of how different particles might be seen to function very much like the way letters function in a text (a "T" is always a T; the specific T is meaningless, only its role in a word matters). Words are made up of letters, but words can have properties like "adjective" or "noun." Their traits don't come from their parts. Then, their role as subject or predicate in a sentence is further not derived from their letters, but by their relationship to other words. — Count Timothy von Icarus

The "role" of a thing, like its function, is an attribute of its context, which presumes a larger whole. The problem though is that we cannot entirely remove meaning from the thing by negating or ignoring the context. So meaning is not completely determined by context, resulting in some form of intrinsic meaning inherent within the thing, as the thing which it is according to its form (law of identity). So we might say the meaning of a word is dependent on the context of usage, but this is not entirely true, or absolute, because there must be something intrinsic within the word, or else any combination of words could have any meaning, and we couldn't figure out any meaning. So the word has some built in limitations which restrict the scope of its usage. Likewise, in you example of letters, the symbol "T" has built in limitations as to acceptable usage, as a letter for example, and we cannot accurately say that the generic "T" "is meaningless", and "only its role in a word matters".

But then which letter/concept in a word holds the trait "noun?" Which parts can be summed up into the concept "noun?" This property can't just be attributed to the rules of spelling, the way the rules of geometry denote "triangle" from the slope of a triangle's three lines, because random mixes of letters can be proper nouns in fiction novels and we create new words all the time. — Count Timothy von Icarus

In general, the narrower, more restrictive concept, holds within it, the broader, less restrictive, as explained by Aristotle. So the concept "man" holds within it, as a defining feature, the concept of "animal", which holds within it, "living", etc.. In this way, "living" is an essential part of "animal", which is an essential part of "man". So "sentence" has "noun" within it, as a defining feature, "sentence being the narrower or stricter, while "noun" is the broader concept. Therefore "noun" is a trait of "sentence", like "animal" is a trait of "man".

When we get to the very particular, the individual, what Aristotle calls primary substance, we see that it is not within anything. So "animal" is within "man", and "man" is within "Socrates", but "Socrates" being a name (proper noun) referring to an individual, is not within any further concept. This allows that the proper noun has no restrictions, not being within anything, so a name could be a random mix of letters, or whatever, and the name is valid or true, substantiated, by the individual which it refers to. The individual has an identity, or existence according to the law of identity.

If the individual named is fictitious, and it is claimed that this individual is supposed to be a real individual, then we have a form of sophistry because the named thing is really a specific concept within a conceptual structure. So the named fictitious thing, Santa Clause for example, is really within, and dependent on a conceptual structure, whereas Socrates names a thing outside and independent of conceptual structure. When it comes to "photon" and other fundamental particles, the named thing is within a conceptual structure supported by observation. So it's halfway between fiction and nonfiction, the conceptual structure is supported by some sort of observational data, but the substantial existence of the thing named as "photon X" cannot be validated through temporal continuity, so it is not really a thing with identity, as primary substance is supposed to be.

So, if traits are actually just parts, I'm not sure I see a way for propositions such as "the block Thomas picked up is triangular," can have truth values. Because the block is actually made up of atoms that aren't triangular, and if you say that the triangularity comes from the block's parts, then you are admitting that objects can have traits that their parts lack, and of course "being made of atoms" isn't necissary or sufficient as a cause of being triangular. — Count Timothy von Icarus

I don't see the problem. The block is an object, and is therefore primary substance. We can name it, and the name becomes the subject, and we predicate. The block is shaped like a pyramid. If we say that the block is really atoms, then we have made the atoms into the objects, or named subjects, and the block is something made from the relations of those atoms. But the atoms are now supposed to be the individual objects we are talking about, the primary substances, not the block. If real substantial existence cannot be given to the atoms, as is the case with photons, then we are back to talking about the block as the objects, and the atoms only exist within the conceptual structure, not referring to any real particles with substantial existence. -

EugeneW

1.7kInterestingly, there are forms of realism people have proposed where the only universals/forms are the fundemental particles. I've never seen nominalism of this sort before, but I could see how it would work. Fundemental particles would be the only tropes, and tropes would really just be names for the excitations of quantum fields we observe. — Count Timothy von Icarus

EugeneW

1.7kInterestingly, there are forms of realism people have proposed where the only universals/forms are the fundemental particles. I've never seen nominalism of this sort before, but I could see how it would work. Fundemental particles would be the only tropes, and tropes would really just be names for the excitations of quantum fields we observe. — Count Timothy von Icarus

It could be that fundamental particles are structures of space. If you consider an elementary an object in a 6d space of which 3 are curled up to tiny Planck-sized dimensions they appear pointlike and can be on top of each other without becoming a singularity as in a black hole. Lots of problems would be solved, like a Lorentz-invsriant invariant Planck length and the already mentioned avoidance of the singularity. -

Alkis Piskas

2.1k

Alkis Piskas

2.1k

From my experience in TPF, I can't say that physicalism as a subject is at the focus. Rather the opposite. It's quite scarce. But this is of no surprise, since, based on a poll I carried out about 7 months ago and also discussions I have had, about 80% of the people in here are "materialists", well, labels aside, they believe that everything that exists is matter or ibased on matter". So, indeed what's the purpose of making physicalism or materialism a central subject?Is it that the focus given to physicalism is due because it is truly central to philosophical discourse, or is it just an accident that occurred by coincidence due to the interests of the forum's userbase? — Kuro

Nevertheless. I fully undestand your saying that "it does not strike me to have such importance of a philosophical topic". You can see more about this in my topic "The problem with "Materialism" at https://thephilosophyforum.com/discussion/12480/the-problem-with-materialism/p1. -

Gnomon

4.3k

Gnomon

4.3k

That is a prescient observation. Both "Consciousness" and "Charge" seem to be intrinsic to matter. But to this day nobody knows what "Charge" is. The etymology literally refers to the "load" that a cart carries. But a wheeled cart could carry a variety of things as its "charge". So, the word is a place-keeper for a more specific definition. Like "Consciousness", empirical science takes its existence -- as an intrinsic property -- for granted -- because of what it does -- but cannot say exactly what it is. My philosophical guess is that Consciousness & Charge & Mass are various forms of Energy : the ability to cause change, to transform. But, what then is Energy or Force made of?The mental resides in matter. Like charge in an electron. — EugeneW

All of these mysterious "properties" are essences, not substances. Which is why empirical Science has to accept them for their functions, even though they can't say what their substance is. As suggested by the "intrinsic property" definition below, what all of these essences have in common is that they are relationships-between-points, not physical objects. The things related can be Physical objects, but the relationships are more like Mathematical ratios (relative values). Hence, a "Charge" can be imagined as the monetary value of a load of potatoes, or sheep, or bread-loaves. But a "monetary value" is simply an idea in a mind. So round & round we go.

Relationships are immaterial links, which can't be seen or touched, so they must be inferred by human "Reason", which "sees" the logical connections between things (see graphic below). And "Logic" is the essence of Semantics : the personal metaphorical or symbolic meanings we attribute to things, as-if their meaning was intrinsic, instead of extrinsic. Likewise, we can say that "Mind" is the function of a brain that sees (imagines) non-physical connections, or relative values, or logical conjunctions between concepts. But what then is "Mind" made of : some abstract ability to bind parts together into whole systems, or to analyze systems into component parts? That mental power itself has no known components -- it just is (Qualia, not Quanta). :cool:

Charge :

Middle English (in the general senses ‘to load’ and ‘a load’), from Old French charger (verb), charge (noun), from late Latin carricare, carcare ‘to load’, from Latin carrus ‘wheeled vehicle’.

___Oxford Dictionary

Intrinsic property :

An intrinsic property is a property that an object or a thing has of itself, including its context. An extrinsic (or relational) property is a property that depends on a thing's relationship with other things.

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Intrinsic_and_extrinsic_properties_(philosophy)

Essence : the intrinsic nature or indispensable quality of something, especially something abstract, that determines its character.

Q. What’s the nature of a charge or what gives a particle a negative charge or a positive one?

A. Simple answer is: we don't know.

It is simply an observation of reality that some elementary particles have an intrinsic property that we attribute to a charge. . . . Just as matter particles have an intrinsic mass property, so do charged particles have a charge.

https://www.quora.com/I-m-looking-for-a-philosophical-POV-on-what-exactly-a-charge-as-in-a-charged-particle-e-g-electron-really-means-How-and-what-really-is-a-charge

-

EugeneW

1.7kBut to this day nobody knows what "Charge" is. — Gnomon

EugeneW

1.7kBut to this day nobody knows what "Charge" is. — Gnomon

And I think we'll never know, as it's inside the particle. We can't know what the inside of a particle exactly is. Which implies that we can't explain consciousness. Of course we eat loads of charges each day. They become part of our total charge, so to speak. And we know how that feels like. Kind of you are what you eat. You can have 1001 explanations of charge, vibrational string modes, or coupling strength to fields, the true nature will stay a mystery. A longing maybe? -

Gnomon

4.3k

Gnomon

4.3k

Yes. Empirical evidence for the inner being of an electron may never be available. That's primarily because electrons are currently assumed to have no internal physical structure for dissecting scientists to analyze. However, that minor obstacle has never stopped theoretical scientists & philosophers from using their X-ray vision (imagination) to speculate on those opaque innards. For example, even a Neutron, with no charge, still contains Energy. So, we could assume that, like Mass, an Electron is made of Energy, which is not a material substance, but merely the potential for change.And I think we'll never know, as it's inside the particle. — EugeneW

Therefore, turning their attention to energy-in-general, some theorists have concluded that "Energy is Information". Moreover since, before Shannon, "information" was the common name for the intangible contents of a Mind (ideas ; thoughts ; memories ; intentions), we can guess that both Energy & Information are somehow related to Conscious Knowing. So, it seems that shape-shifting Energy takes on many different forms, from electron "Charge", to the "Mass" of matter, and even to the "Mind" of a brain. Consequently, some theoretical scientists have deduced that Energy/Information (my term : EnFormAction) is the fundamental substance of the universe. If so, what does that equation of Matter & Mind mean for the "metaphysical theory" of Physicalism? :gasp:

What is an electron made of? :

Electrons are fundamental particles so they cannot be decomposed into constituents. They are therefore not made or composed. An electron acts as a point charge and a point mass.

https://www.quora.com/What-are-electrons-made-up-of-Are-all-electrons-made-of-the-same-material

How is information related to energy in physics? :

Energy is the relationship between information regimes. That is, energy is manifested, at any level, between structures, processes and systems of information in all of its forms, and all entities in this universe is composed of information.

https://physics.stackexchange.com/questions/22084/how-is-information-related-to-energy-in-physics

Is ‘Information’ Fundamental for a Scientific Theory of Consciousness?

After a brief primer on Shannon’s information, we are led to the exciting proposition of David Chalmers’ ‘double-aspect information’ as a bridge between physical and phenomenal aspects of reality.

https://link.springer.com/chapter/10.1007/978-981-10-5777-9_21

In philosophy, physicalism is the metaphysical thesis that "everything is physical", that there is "nothing over and above" the physical, or that everything supervenes on the physical.

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Physicalism -

EugeneW

1.7kNice comment! Allow me to offer some critique (it's a philosophy forum,so...).

EugeneW

1.7kNice comment! Allow me to offer some critique (it's a philosophy forum,so...).

Currently the observations are such that the pointlike structure of electrons isn't challenged. One can dive into the electron by the power of imagination. I think all empirical data can be explained by considering electrons, like all quarks and other leptons, composite. Triplets of massless preons (linking pure kinetic particle energy with mass!) explain a lot of hitherherto unexplained phenomena in physics (particle/antiparticle asymmetry, particle families, force unification, etc.) but even proposing this or questioning on philosophy forums why this model is impopular gets you banned. It's an attack on the standard of pointlike standards and the basis of string theory would be endangered. The politics of power are employed to protect the sancta casa. The muon g2 experiment can be interpreted though in the light of compositeness. But this approach is not even considered. I don't understand why and no one was able to give convincing arguments against it. A ban was all they had eventually. The preons themselves can even be considered structures of space in which charges can be enclosed. So mass is a derivative of pure kinetic energy in massless particles. The content, charges, of particles is the unexplainable "mental" component.

I don't see the connection between information and mind. What's the connection between structure and mind? Of course, the structure of particles having a global shape, invisible at the small scale, is not physical. Particles in the shape of, say, a simple circle don't have necessarily a physical connection with diametrically opposite particles. Still they share a commodity. Otherwise the circle could not have its shape. But to say the shape is the mental? Dunno...

Welcome to The Philosophy Forum!

Get involved in philosophical discussions about knowledge, truth, language, consciousness, science, politics, religion, logic and mathematics, art, history, and lots more. No ads, no clutter, and very little agreement — just fascinating conversations.

Categories

- Guest category

- Phil. Writing Challenge - June 2025

- The Lounge

- General Philosophy

- Metaphysics & Epistemology

- Philosophy of Mind

- Ethics

- Political Philosophy

- Philosophy of Art

- Logic & Philosophy of Mathematics

- Philosophy of Religion

- Philosophy of Science

- Philosophy of Language

- Interesting Stuff

- Politics and Current Affairs

- Humanities and Social Sciences

- Science and Technology

- Non-English Discussion

- German Discussion

- Spanish Discussion

- Learning Centre

- Resources

- Books and Papers

- Reading groups

- Questions

- Guest Speakers

- David Pearce

- Massimo Pigliucci

- Debates

- Debate Proposals

- Debate Discussion

- Feedback

- Article submissions

- About TPF

- Help

More Discussions

- Other sites we like

- Social media

- Terms of Service

- Sign In

- Created with PlushForums

- © 2026 The Philosophy Forum