-

What is 'Mind' and to What Extent is this a Question of Psychology or Philosophy?Is there some problem we need to solve with this information that is fruitful somehow beyond the questioning? — Metaphyzik

There is a subject, philosophy of mind. I believe you referred to David Chalmer's homepage the other day, that's his main subject matter. -

What is 'Mind' and to What Extent is this a Question of Psychology or Philosophy?We too, in Reality, are beings driven by evolution to respond to triggers in various ways. — ENOAH

Isn't that 'biological reductionism'? -

Graham Oppy's Argument From Parsimony For NaturalismThe element that is generally absent in many of these discussions is the element of cognitive transformation that characterises the kinds of insights being discussed. Instances can be cited from the earliest strata of philosophy, one being the prose-poem of Parmenides, which encompasses a mystical element from the beginning:

The introductory section of Parmenides’ philosophical poem begins, “The mares that carry me as far as my spirit [θυμὸς] aspires escorted me …” (B 1.1– 2). He then describes his chariot-ride to “the gates of night and day,” (B 1.11) the opening of these gates by Justice, his passage though them, and his reception by a Goddess, perhaps Justice herself. The introduction concludes with her telling him, “It is needful that you learn all things [πάντα], whether the untrembling heart of well-rounded truth or the opinions of mortals in which is no true belief” (B 1.28–30). From the outset, then, we are engaged with the urgent drive of the inmost center of the self, the θυμὸς, toward its parmenides 13 uttermost desire, the apprehension of being as a whole, “all things.”2 Since the rest of the poem is presented as the speech of the Goddess, this grasp of the whole is received as a gift, a revelation from the divine. — Eric D Perl, Thinking Being

In other texts, the reference to the 'gates of day and night' are interpreted as a clear reference to non-dualism. In any case, as is often stated, Parmenides is recognised as one of the sources of Western philosophy generally and of metaphysics in particular.

'I can't understand this' or 'it doesn't make sense to me' or 'I don't see how that is possible', don't constitute arguments.

The proper demand is: show me evidence (facts) that can't be explained by naturalism. — Relativist

As already stated, naturalism assumes an order of nature, without which it wouldn't be able to get started. But it doesn't explain the order of nature - nor does it need to. For all practical purposes, it doesn't really make any difference. Natural theology is able to rationally argue that the fact of the order is itself an indication of a prior intelligence, through arguments such as the cosmological anthropic principle. The fact that such arguments may be inconclusive or beyond adjutication does not make them irrational. -

What is 'Mind' and to What Extent is this a Question of Psychology or Philosophy?At the time of reading his writing I did think his perspective would be a foundation for belief in reincarnation, even though I am unsure if Sheldrake would go that far. — Jack Cummins

See this interview.

His theory of morphic resonance posits that there is a kind of collective memory accessible to individuals, which can manifest as memories that seem to come from past lives. This theory sits at the intersection of science and spirituality, suggesting that phenomena often attributed to reincarnation could instead be understood through a shared, collective memory framework.

Sheldrake's approach allows for the acknowledgment and acceptance of memories of past lives without necessitating belief in reincarnation as the migration of a soul or person from one body to another across lifetimes. Instead, it suggests that individuals might "tune into" memories from the collective past, which could explain why some people have vivid, detailed recollections that seem to be from lives they never lived.

This idea finds a parallel in Buddhist teachings on rebirth, where continuity from one life to the next is not that of an individual, but rather a stream of consciousness (citta-santana) conditioned by karma. In Buddhism, there is no static self or soul that transmigrates, but a causal matrix of mental and physical conditions forms as a being, due to actions and intentions set in motion in previous lives. -

Grundlagenkrise and metaphysics of mathematicsI recall an article about how geometry began in Egypt - obviously the construction of the Pyramids required advanced geometry but well before that it was used to allocate plots of farming land on the Nile delta. It will be recalled that this floods every year and the boundaries are erased, so every year the plots have to be allocated anew along the sides of the river-banks, which required sophisticated reckoning. The origins of arithmetic were likewise associated with the Babylonian-Sumerian culture - the ‘cradle of civilisation’ - for reckoning cattle numbers and storage of crops. You can see how arithmetic generally would be associated with ownership, building, cultivation of crops and conversely how it would not be of much relevance to hunter-gatherer cultures.

-

Graham Oppy's Argument From Parsimony For NaturalismWhat is my purpose? Where do I ultimately come from? Why do bad things sometimes happen? What is justice, or love for that matter? Can naturalism explain these questions in a satisfying way? — NotAristotle

From the naturalistic viewpoint, the answers are to be sought in terms of evolutionary development, a pragmatic philosophy and a utilitarian outlook. Justice and love are the adaptations of social hominids. And so on. Combined with democratic liberalism, there's nothing inherently wrong with it, but whether it is all there is to life is an open question. (And at least, in democratic liberal cultures, one which we're free to pursue.)

A useful essay by John Hick. He was an English philosopher of religion, notable for his commitment to religious pluralism. Rather a dense academic work, but then, it is a philosophy forum! - Who or What is God?

The basic principle that we are aware of anything, not as it is in itself unobserved, but always and necessarily as it appears to beings with our particular cognitive equipment, was brilliantly stated by Aquinas when he said that ‘Things known are in the knower according to the mode of the knower’ (S.T., II/II, Q. 1, art. 2). And in the case of religious awareness, the mode of the knower differs significantly from religion to religion. And so my hypothesis is that the ultimate reality of which the religions speak, and which we refer to as God, is being differently conceived, and therefore differently experienced, and therefore differently responded to, in historical forms of life within the different religious traditions.

What does this mean for the different, and often conflicting, belief-systems of the religions? It means that they are descriptions of different manifestations of the Ultimate; and as such they do not conflict with one another. They each arise from some immensely powerful moment or period of religious experience, notably the Buddha’s experience of enlightenment under the Bo tree at Bodh Gaya, Jesus’ sense of the presence of the heavenly Father, Muhammad’s experience of hearing the words that became the Qur’an, and also the experiences of Vedic sages, of Hebrew prophets, of Taoist sages. But these experiences are always formed in the terms available to that individual or community at that time and are then further elaborated within the resulting new religious movements. — John Hick -

Grundlagenkrise and metaphysics of mathematicsanother layer of explanation that this theory would require. — Lionino

I think the confusion revolves around the equivocation of the term 'object' in 'mathematical object'. Numbers are not actually objects in any sense but the allegorical. There is no object '2'. What there is, is the act of counting which is denoted by the symbol '2'.

Step back a little. You may recall an allegory that dates back to the 19th century, about how a two-dimensional surface of water would perceive a three-dimensional cone. Absent any idea of a third dimension, the surface could only ever perceive the cone in terms of concentric circles //and ellipses//. Then there'd be this big conceptual problem as to how all these circles are related. You could write an equation, presumably, that described the progression of circles, but you still wouldn't be seeing what they represent.

I think there's something analogous to that operating in this argument. The cone analogy is a metaphor for the limitations inherent in empiricist understanding (akin to pistis or doxa in Plato's terms), which cannot by itself grasp the sense in which mathematical knowledge is 'higher'. There is no higher! There's only the flatland of empirical reality mediated by physical senses. Just as the two-dimensional surface perceives only the cross-sections of a cone, without a conception of the three-dimensional object itself, empirical observation alone cannot fully comprehend the abstract realities that Platonists argue transcend physical particulars. This analogy underscores the empiricist critique of Platonism, suggesting that notions of 'higher' or 'abstract' truths, such as mathematical entities, are outside the domain of of empirical verification and as such cannot be explained in those terms.

And the diagram you provide illustrates the problem, as it's two-dimensional. I think that what happens in reality, is that rational inference (including counting) operates on a different level, but in concert with, sensory cognition (per Kant). Whereas the diagram seeks to treat them in the same way, that is, as objects, and then asks how they're related. It's a category problem, which ultimately originates in the 'flattening' of ontology that occurs with the transition to the modern world-view (hence the relevance of the 'flatland' argument.) Hence, it's a metaphysical problem, but as the proponents of empiricism are averse to metaphysics, they of course will not be able to acknowledge that.

The problem is still how that faculty works to understand mathematical truths. It seems no one has given a satisfactory explanation. — Lionino

Mathematics is what explains. We don't need to explain arithmetical primitives, they are what provides the basis of explanation. Trying to explain mathematics by reducing those faculties to the sensory is the source of the problem. -

The Blind Spot of Science and the Neglect of Lived ExperienceThe overwhelming majority of scientists will agree that it is matter that will explain things like entanglement and local gravity — Lionino

So, if there are anomolies in the movement of galaxies, they can only be due to matter, even if it is of a kind we have no knowledge of. Because, what else is there? -

What is 'Mind' and to What Extent is this a Question of Psychology or Philosophy?I don't believe that 'mind' can be reduced to psychology, because it is at the core of human existence. So, in the light of cognitive science and neuroscience, how, and what do you see as the overriding and outstanding issues of the philosophy of mind in the twentieth first century? Is there any essential debate beyond the scope of psychology? — Jack Cummins

The brutal fact of the matter, Jack, is that as far as mainstream science and academic philosophy is concerned, 'mind is what brain does'. In the mainstream, it is viewed squarely through the perspectives of neuroscience, evolutionary biology, and pyschology, and those who dissent are invariably characterised as fringe or new-age - the author you cite would doubtlessly be described as such by a lot of people.

Surveys in academic philosophy, as Banno frequently points out, show only a very small percentage of respondents support or advocate for philosophical idealism (from memory, less than 2%.) The majority, presumably, operate under a paradigm such as reductive or non-reductive physicalism or something of the kind.

There is a US University department, the Division of Perceptual Studies at University of Virginia, founded by past-life memories researcher Ian Stevenson, which is devoted to paranormal psychology. You'll find their published books on philosophy of mind and paranormal psychology here. There's also a thriving industry of books and videos devoted to these ideas, they're certainly not bereft of an audience, but most universities won't go near them.

As far as 'mind fields' are concerned, I think Rupert Sheldrake is one source, although his ideas extend beyond philosophy of mind per se. He is often derided as a crackpot - Steve Pinker and others say he's a pseudo-scientist - but he at least has a seat at the table, so to speak. His website is at sheldrake.org. This video interview also seems relevant.

A question I ponder is, if there are fields other than electromagnetic fields - the existence of which is clearly demonstrable - how would they be detected? By what instruments? Sheldrake's 'morphic fields' are related to earlier ideas of morphogenetic fields which have fallen out of favour, but were regarded as part of the mainstream at the time. One analogy I think makes kind of sense is the body/mind as being more like a receiver or transmitter of consciousness rather than the originator of it. But of course that leaves a lot of open questions. (It is one of the ideas discussed by Sheldrake in the video cited above.)

I am hoping that I am not raising a stale and overtired area of thinking, especially in relation to the mind-body relationship, as well as between idealism and physicalism — Jack Cummins

Afraid so, but don't let that stop you. -

Grundlagenkrise and metaphysics of mathematicsCouldn’t a logicist also be a nominalist? — Lionino

That is one very deep and dense OP. I'll acknowledge that I'm not a mathematician and that many of the concepts you're discussing are beyond me. I think, of the above, what makes sense to me is intuitionism.

I've become interested in the topic because of the argument that numbers are real but not material, which is an embarrasment to most typical forms of contemporary naturalism, which is dogmatically physicalist. For example:

What is Benacerraf's problem? Perhaps the main problem for mathematical platonism, or lower-case platonism in general, is, if numbers are causally inert objects, how could it be that we have any knowledge of them, given we don't interact with them at all? — Lionino

It's not a problem for platonism, but a problem for naturalistic or empiricist accounts of knowledge. The question is, how can we know numbers, if they are purely intelligible in nature?

There's another article on this topic, The Indispensability Argument in the Philosophy of Mathematics which also leads with Benecareff. It starts:

In his seminal 1973 paper, “Mathematical Truth,” Paul Benacerraf presented a problem facing all accounts of mathematical truth and knowledge. Standard readings of mathematical claims entail the existence of mathematical objects. But, our best epistemic theories seem to deny that knowledge of mathematical objects is possible.

So, what are these 'best epistemic theories' and why do they seem to deny such knowledge? Why, it's because:

Mathematical objects are in many ways unlike ordinary physical objects such as trees and cars. We learn about ordinary objects, at least in part, by using our senses. It is not obvious that we learn about mathematical objects this way.

Doesn't that simply amount to problem for empiricism, i.e. the view that knowledge is attained mainly through sense-perception? So if mathematical knowledge is hard to square with empiricism, then so much the worse for it, I would have thought, considering how 'indispensable' it actually is for science itself.

It goes on:

(Rationalist) philosophers claim that we have a special, non-sensory capacity for understanding mathematical truths, a rational insight arising from pure thought. But, the rationalist’s claims appear incompatible with an understanding of human beings as physical creatures whose capacities for learning are exhausted by our physical bodies.

So instead of questioning why it is we can understand numbers, how about interrogating the claim that we are, in fact, 'physical creatures whose capacities for learning are exhausted by our physical bodies?' Or is that such an important principle in our 'best epistemic theories' that it has to be saved at all costs? That seems the point of the sophistry of the 'indispensability argument'.

So perhaps the 'crisis' is actually a manifestation of a problem at the foundations of naturalism itself, but it's kind of an 'emperor's new mind' type of scenario where nobody wants to admit it. Philosophical dualism and mathematical platonism have no such difficulties. But as it is, and as your cited SEP article on Platonism in Philosophy of Mathematics says,

Mathematical platonism has considerable philosophical significance. If the view is true, it will put great pressure on the physicalist idea that reality is exhausted by the physical. For platonism entails that reality extends far beyond the physical world and includes objects that aren’t part of the causal and spatiotemporal order studied by the physical sciences.[1] Mathematical platonism, if true, will also put great pressure on many naturalistic theories of knowledge. For there is little doubt that we possess mathematical knowledge. The truth of mathematical platonism would therefore establish that we have knowledge of abstract (and thus causally inefficacious) objects. This would be an important discovery, which many naturalistic theories of knowledge would struggle to accommodate.

Oh, and as for the question I quoted - from my limited understanding, Frege, who had quite a bit to say about that, believed in the reality of abstract objects, which nominalism explicitly does not. See Frege on Knowing the Third Realm, Tyler Burge (public domain.) -

Graham Oppy's Argument From Parsimony For NaturalismOh, I think I understand now: you are saying that, because you don’t think the examples which you have readily available are legitimate sources (or are problematic), that you can’t give any example of a phenomena that requires supernaturalism to account for it, correct? — Bob Ross

Yes, that's generally what I was getting at. Added to that, the difficulty involved in vaidating or falsifying accounts of anything so-called 'supernatural' in a controlled environment.

Are you saying that miracles require a form of supernaturalism to account sufficiently for them? — Bob Ross

:chin: Isn't that what you asked for?

is there anything which seems to demand we posit, conceptually, something supernatural? — Bob Ross

I would have thought that 'miracle cures due to prayers' would fit that bill rather nicely. The account I linked to was from a medical scientist, Jacalyn Duffin, who was called to give evidence at an ecclesiastical tribunal. This tribunal was tasked with discerning whether a case of permanent remission from a usually-fatal form of leukemia could be attributed to the prayers of one Marie-Marguerite d’Youville, the founder of the Order of Sisters of Charity of Montreal and a candidate for canonization.

Duffin, who says she is atheist, and is an historian of medicine as well as a haemotologist, had her interest sufficiently piqued by the case to research and write several books on such cases.

You may be aware that the saying 'the devil's advocate' originated with such ecclesiastical enquiries. The role of the devil's advocate was to aggressively question the evidence of miracles to establish whether they had a natural explanation. Indeed, Duffin notes in the article that she 'never expected such reverse scepticism and emphasis on science within the Church', saying that the majority of such enquiries result in dismissing the purported miracles and declaring natural causes instead.

So, anyway, the reason that came to mind, is that one of Duffin's books discusses '1400 miracles from six continents and spanning four centuries. Overwhelmingly the miracles cited in canonizations between 1588 and 1999 are healings, and the majority entail medical care and physician testimony.' I'm not saying that you or anyone should draw any conclusions from that, but so far as empirical evidence is concerned, that at least constitutes a respectable data set, and one which does have bearing on the question.

As far as Rupert Sheldrake is concerned, if you're not familiar with him, it's a long story to tell. He's routinely described as a maverick scientist (or 'crackpot theorist') for his initial research in something he designated 'morphic resonance', the tendency of nature to form habits. His initial book was fiercely denounced, with the then-editor of Nature saying it was a candidate for burning. He is, however, an actual scientist, a plant biologist, and claims to have evidence in support. He also has written on telepathic effects, such as the 'sense of being stared at' and 'dogs who know when their owners are about to come home', for which there is no physical explanation. He's a frequent guest on discussion panels nowadays, alongside contemporary philosophers and public intellectuals. Again not saying you or anyone should believe what he says, but it's worth noting in the context. You can find more information at https://www.sheldrake.org/.

are natural laws part of nature?

Yes. — Bob Ross

The philosophical arguments are more subtle. Academics like Nancy Cartwright (see No God, No Laws) have critically addressed the problematic nature of referring to observed natural regularities as 'laws', by asking in what sense they can be considered laws at all if not decreed or enforced by an authority. Her critique underscores a broader skepticism about the metaphysical foundations of scientific laws, suggesting they are better understood as descriptions of consistent patterns or behaviors in nature rather than prescriptive rules imposed upon it. It also throws into relief whether the status of scientific laws is itself a scientific question; arguably, it is not. The consideration of the nature of these laws belongs more in the realm of metaphysics and philosophy, where the focus shifts from empirical validation to conceptual analysis. Whereas, naturalism tends to simply assume these laws, but itself has no explanation for them.

In practice, 'naturalism' often amounts to a kind of demarcation between 'rational science' and 'superstitious religion' (a.k.a. 'woo'), but it's also part of the debate between physicalism and idealism in philosophy. -

Donald Trump (All General Trump Conversations Here)Trump Criminal Trial Is Set for April 15 as His Attempt at Delay Fails

Donald J. Trump is all but certain to become the first former American president to stand trial on criminal charges after a judge on Monday denied his effort to delay the proceeding and confirmed it would begin next month.

The trial, in which Mr. Trump will be accused of orchestrating the cover-up of a simmering sex scandal surrounding his 2016 presidential campaign, had originally been scheduled to start this week. But the judge, Juan M. Merchan, had pushed the start date to April 15 to allow Mr. Trump’s lawyers to review newly disclosed documents from a related federal investigation.

Mr. Trump’s lawyers had pushed for an even longer delay of 90 days and sought to have the case thrown out altogether. But in an hourlong hearing Monday, Justice Merchan slammed their arguments, rejecting them all. -

Graham Oppy's Argument From Parsimony For NaturalismBut how would you find out? In the absence of that kind of data, what criteria can be selected?

What do you mean? — Bob Ross

Go back a few steps - you asked:

it isn’t demanding a proof, per se, of God’s existence: it is demanding an example, at a bare minimum, of a phenomena (i.e, an appearance: event) which cannot be explained more parsimoniously with naturalism — Bob Ross

To which I responded:

Well, given the tendency to reject every account that is found in the world’s religious literature of such events, then probably not — Wayfarer

because accounts of Biblical miracles, and miraculous events described in other religious literature, might constitute the kinds of examples you're referring to, but as a rule these are not considered, because they're not replicable and generally not considered credible by any modern standards. So what examples are being referred to? Where to look for the data?

As it happens, there is one large body of records collected concerning allegedly supernatural events, which are the investigations of miracles attributed to those being considered for canonization as saints by the Catholic Church. These alleged interventions are the subject of rigorous examination - see Pondering Miracles.

Aside from those, I mentioned Rupert Sheldrake's research in telepathic cognition, which is considered supernatural by some, in that it seems to require that there is a non-physical medium through which perceptions and thoughts are transmitted.

Both these appeal to empirical data. The following argument is philosophical.

For intents of this OP, naturalism is the view that everything in reality is a part of the processes of nature; and supernaturalism is the view that some things transcend those processes of nature. — Bob Ross

In order to declare that everything is 'a part of the processes of nature' we need to understand where the boundary lies between what is natural and what might be supernatural. I simply pointed out that even the metaphysical status of natural laws is itself contested: are natural laws part of nature? It seems obvious, but it is contested by philosophers, and it is a question that itself not scientific, but philosophical.

Furthermore, where in nature do your examples of inductive and deductive logic exist? As far as I can tell, they are purely internal to acts of reasoned inference, they're internal to thought. Science never tires of telling us that nature is blind and acts without reason, save material causation; so can reason itself explained in terms of 'natural laws'? -

The Gospels: What May have Actually HappenedBefore Abraham was, I am." — If Jesus Never Called Himself God, How Did He Become One?

Not ego speaking. The ‘I Am’ is the ‘I AM’ of Exodus - the ‘I am’ of the Cosmos. That is something imparted by the Advaita guru Ramana Maharishi. Not orthodox doctrine, but :ok: -

The Blind Spot of Science and the Neglect of Lived ExperienceBut why would there never be a physical accounting of consciousness? — Metaphyzik

That is the subject of David Chalmer’s 1996, paper, Facing Up to the Problem of Consciousness, which has triggered a lot of debate. The gist of the argument is that no physical explanation can account for the nature of subjective experience which is by definition first-person, although you’d have to read the paper for the details of the argument.

But the general drift of the Blind Spot argument is against physicalism, which is the belief that everything can be reduced to physics. Hempel’s dilemma is that physics is subject to constant revision, so what we think of as physical, or non-physical, now, might be completely different in 10 or 100 years.

Facing up to the problem of consciousness can be found here https://consc.net/papers/facing.pdf

The original article this thread was based on can be found here

https://aeon.co/essays/the-blind-spot-of-science-is-the-neglect-of-lived-experience -

The Blind Spot of Science and the Neglect of Lived ExperienceCan you image the scientific best guess reality 100 years from now? — Metaphyzik

The article this thread is from distinguishes science per se from physicalism:

the claim that there’s nothing but physical reality is either false or empty. If ‘physical reality’ means reality as physics describes it, then the assertion that only physical phenomena exist is false. Why? Because physical science – including biology and computational neuroscience – doesn’t include an account of consciousness. This is not to say that consciousness is something unnatural or supernatural. The point is that physical science doesn’t include an account of experience; but we know that experience exists, so the claim that the only things that exist are what physical science tells us is false. On the other hand, if ‘physical reality’ means reality according to some future and complete physics, then the claim that there is nothing else but physical reality is empty, because we have no idea what such a future physics will look like, especially in relation to consciousness.

This problem is known as Hempel’s dilemma, named after the illustrious philosopher of science Carl Gustav Hempel (1905-97). Faced with this quandary, some philosophers argue that we should define ‘physical’ such that it rules out radical emergentism (that life and the mind are emergent from but irreducible to physical reality) and panpsychism (that mind is fundamental and exists everywhere, including at the microphysical level). This move would give physicalism a definite content, but at the cost of trying to legislate in advance what ‘physical’ can mean, instead of leaving its meaning to be determined by physics. -

The Blind Spot of Science and the Neglect of Lived ExperienceMy observation was simply the resemblance between that passage from the Republic, which talks of ‘honours’ that the ‘cave-dwellers’ receive for ‘whoever discerns the passing shadows most keenly, and is best at remembering which of them usually comes first or last, which are simultaneous, and on that basis is best able to predict what is going to happen next.’ It seems an apt analogy for particle physics, as nobody really knows if there is an underlying reality, or if so what it comprises. Recall Neils Bohr’s often-quoted aphorism, ‘physics concerns not nature herself, but what we can say about nature’.

At this time, as is well-known, there are challenging fundamental conundrums about the standard model of physics and other matters. All I’m saying is, maybe that is because physics itself is not after all fundamental. But as everything is defined in terms of matter (or matter-energy) then the question is ‘what else could it be’? I would guess there are dissident theorists (and probably some pretty far-out ideas) about that, and I’m not trying to prove the point. I feign no hypothesis - just idle musing. -

How could someone discover that they are bad at reasoning?Would you be okay with accepting a world of consequences without being able to find out what they will be? — Paine

Good question. I suppose it’s analogous to compatibilism in some ways. -

Graham Oppy's Argument From Parsimony For NaturalismI don't think that one needs to limit themselves to what is scientifically peered reviewed or easily replicable. However, every example I have heard seems, to me, to be better explained naturalistically. — Bob Ross

But how would you find out? In the absence of that kind of data, what criteria can be selected? Recall the original point of Popper’s falsifiability was to differentiate empirical claims from other kinds, although it’s now wrongly taken to imply a kind of verificationism. Popper, as it happens, held to a form of dualism, in that he believed in a ‘third realm’ that contains the products of the human mind that, once created, lead an existence independent of their creators. This includes theories, scientific knowledge, mathematical constructs, cultural artifacts, and works of art. According to Popper, World 3 objects can influence both the physical world (World 1) and the mental world (World 2), yet they are not reducible to either. So whether that is a form of naturalism is debatable - and the reason it’s debatable is because the concept of naturalism is constantly changing.

As far as theism and atheism is concerned, the traditional divide formed between naturalistic science, which seeks explanations purely in terms of natural laws, and non-physicalist or metaphysical philosophies which are often but not always associated with religion (another very hard term to define!) But surely, in effect, naturalism leans towards explanations in terms of what have been known as natural laws - but then, there’s a whole other issue there, in philosophy of science, as to whether there are ‘natural laws’ and what that means (per Nancy Cartwright ‘How the Laws of Physics Lie’). And that debate, again, is not itself subject to a naturalist explanation, as it’s ’theory about theory’. -

Graham Oppy's Argument From Parsimony For Naturalismit isn’t demanding a proof, per se, of God’s existence: it is demanding an example, at a bare minimum, of a phenomena (i.e, an appearance: event) which cannot be explained more parsimoniously with naturalism (over supernaturalism)---in other words: is there anything which seems to demand we posit, conceptually, something supernatural? That’s the question. — Bob Ross

Well, given the tendency to reject every account that is found in the world’s religious literature of such events, then probably not. None of those accounts appear in peer-reviewed scientific literature and are probably impossible to replicate (heck, plain old psychological studies are pretty hard to replicate.) So, given all that, you’re probably on pretty safe ground.

I’ve been reviewing a bit of Rupert Sheldrake’s material again. He claims to have evidence of psychic phenomena that call naturalism into question, at least insofar as they’re paranormal. The phenomena he speaks of are fairly quotidian in nature - dogs who know when their owners are about to come home, the sense of being stared at, and so on. He is, of course, characterised as a maverick or crank by a lot of people, but he persists, in his quiet way, and claims to have significant evidence. The argument then turns into one about whether he does present evidence. -

How could someone discover that they are bad at reasoning?And then, suppose he does come to understand that he's bad at reasoning - what then? If he still cares about the truth, but he has come to accept that his tools for discovering or filtering truths are compromised, what should he do? — flannel jesus

I don’t think that would be terribly difficult in a controlled situation - like science, or architecture or engineering. You would find out you were wrong by having your predictions disconfirmed or flaws in your designs or projects (although there are those who are notoriously bad at recognising their own flaws. Like Trevor Milton who started an e-lorry company based on lies and was jailed as a result.)

But it’s a lot more slippery when it comes to moral judgements and ethical decisions, as the criteria are not necessarily objective (I say not necessarily, because if those judgements and decisions cause harm or calamity, those are objective consequences.) But it’s possible to skate through life being wrong about any number of such things, and if there is no karma-upance in a future existence, then - so what? -

Graham Oppy's Argument From Parsimony For NaturalismWhen you demand evidence for belief in God, I think a perfectly rational theistic response is 'look around you, you're standing in it'. From a theistic perspective - not necessarily one that I share, but am sympathetic too - the order of nature is indicative of a prior intelligence. And let's not forget that while science discovers and exploits the order of nature, it doesn't explain it. That's what I mean about the shortcoming of empirical demands - 'show me where this "god" is. You can't produce any evidence'. It's a misplaced demand. But, that said, I'm not going to go all-in to try and win the argument, it's take it or leave it, and most will leave it.

-

The Blind Spot of Science and the Neglect of Lived ExperienceOf course. To say otherwise would be stereotyping. Scientists come from all kinds of cultures and backgrounds and have a huge diversity of views.

-

Graham Oppy's Argument From Parsimony For NaturalismIn short, naturalism is a simpler theory than theism.

There are arguments against naturalism from perspectives other than the theistic. But from a theistic perspective the problem with this argument is that it makes of God one being among others, an explanatory catch-all that is invoked to account for purported gaps in naturalism. In other words, it starts with a naturalist conception of God which is erroneous in principle. Quite why that is then turns out to be impossible to explain, because any argument is viewed through that perspective, for example by the demand for empirical evidence for the transcendent. I think the proper theist response is not to try prove that God is something that exists, but is the ground or cause of anything that exists. That is not an empirical argument.

So, for those who are supernaturalists in this forum: what phenomena do you believe cannot be sufficiently explained naturalistically? — Bob Ross

Phenomena are appearances - that is the origination of the word. And from a non-theistic philosophical perspective, something this doesn’t account for is the nature of the being to whom phenomena appear. -

on the matter of epistemology and ontologyOriginal sin he (Kierkegaard) calls a myth, though no worse than the myths of intellectuals. — Astrophel

Odd, that. I would have thought with all his musing about sin and despair, that it would seem a self-evident truth to him. My personal belief is that it signifies something profoundly real about the human condition, albeit obviously mythological.

the absurd is the experience one has when realizing that whatever stands before one in the world that might be defining as to their true nature, their essence, turns out to be contingent, ephemeral, and entirely "other" than what they are. — Astrophel

Also oddly, perhaps, this resonates with Buddhist attitude of no-self (anatman) and emptiness (śūnyatā), which is also precisely about the lack of any intrinsic self. But in Eastern culture, so far as I know, that is not described in terms of the absurd. -

US Election 2024 (All general discussion)I know all of that. Furthermore, they were forced to drop a motion to firewall off any Party finances from Trump's enormous legal expenses. He completely owns the Republican Party, and if and when he fails at the polls or is incarcerated, they'll be so much the worse for it. (In fact for Democrats, Trump might end up being boon rather than a bane.)

-

Classical theism and William Lane Craig's theistic personalismWell, I might chip in. I did a bit of research, and found a blog post by Edward Feser (representing classical theism) critiquing William Lane Craig:

...the problem with the thesis that “God is a person” is not the word “person,” but rather the word “a.” And as Davies (in Introduction to the Philosophy of Religion) and I have argued many times, there are two key problems with it - a philosophical problem, and a distinctively Christian theological problem.

The philosophical problem is that this language implies that God is a particular instance of the general kind “person,” and anything that is an instance of any kind is composite rather than simple, and thus requires a cause. Thus, nothing that is an instance of a kind could be God, who is of course essentially uncaused. (Obviously these claims need spelling out and defense, but of course I and other Thomists have spelled them out and defended them in detail many times.) The distinctively Christian theological problem is that God is Trinitarian -- three divine Persons in one substance -- and thus cannot be characterized as “a person” on pain of heresy. …

So, the reason Davies labels the rejection of classical theism “theistic personalism” is not that he thinks God is impersonal. The reason is rather that he takes theistic personalists to start with the idea that God is a particular instance of the general kind “person” and to go from there. And this, he thinks, is what leads them to draw conclusions incompatible with classical theism, such as that God is (like the persons we’re familiar with in everyday experience) changeable, temporal, made up of parts, etc. To reject theistic personalism, then, is not a matter of regarding God as impersonal, but rather a matter of rejecting the idea that God is a particular instance of the kind “person,” or of any other kind for that matter. — Edward Feser

So the argument, essentially, is that Craig (and theistic personalism generally) view God as a person, a particular being, in anthropomorphic terms - a person like us, only perfect. The infinite regress arises from the claim that if God is a particular being, then in some sense he must be caused, as all particulars exist as the result of causes - as Feser says, 'anything that is an instance of any kind is composite rather than simple, and thus requires a cause.'

I think the conflict arises as a consequence of Craig's Protestantism which tends to deprecate the classical metaphysics found in Aquinas (Feser describes himself as 'Aristotelian-Thomist') and other pre-modern theologies. Protestantism often leans towards the literal interpretation of scripture, citing 'sola scriptura'. The most obvious form of that is creationist fundamentalism, granted, a minority view but still representing an influential current in Protestant Christianity. Aquinas sought to accomodate elements of Aristotle, for which he was criticized by Luther. Protestant theology looks on metaphysics, which ultimately derives from Greek rather than Biblical sources, with suspicion. That's where I see the root of the conflict. -

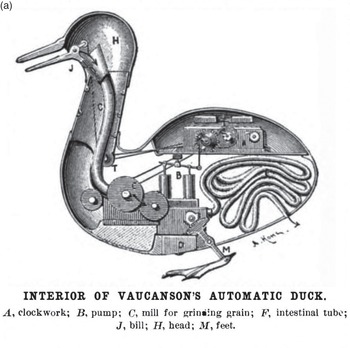

Descartes and Animal CrueltyThere is, however, little doubt that Descartes did believe that animals were essentially no different to machines. He identified 'the soul' as the rational faculty of humans - a view which has considerable provenance - but he interpreted it in a rather absolutistic way. He believe the human body was essentially mechanistic, governed by the immaterial soul, which he said interacted with the body through the pineal gland, but that we humans experience emotions and feelings due to the presence of the soul. So he viewed non-human animals, lacking a rational soul, as machines, as depicted in Monsieur Vaucanson's well-known mechanical duck, which served to illustrate Descartes view (in De Homine, 1662) that all animals could be reductively explained as automata.

-

The Blind Spot of Science and the Neglect of Lived ExperienceWe might accept G.M D’Ariano's claim that particles are like "the shadows on the walls of Plato's cave," — Count Timothy von Icarus

Here is passage that is particularly relevant. Socrates and Glaucon are discussing what happens when those who have passed through 'the difficult passage' out of the cave return to it, out of compassion for those remaining, who are the subjects of the first paragraph:

“And suppose they received certain honours and praises from one another, and there were privileges for whoever discerns the passing shadows most keenly, and is best at remembering which of them usually comes first or last, which are simultaneous, and on that basis is best able to predict what is going to happen next. Do you think he would have any desire for these prizes, or envy those who are honoured by the prisoners and hold power over them? Or would he much prefer the fate described by Homer and ‘work as a serf for a man with no land’, and suffer anything at all, rather than hold their opinions and live as they do?”

“I think it is just as you say. He would accept any fate rather than live as they do.”

“Yes, and think about this,” I said. “If such a person were to go back down, and sit in the same seat, would not his eyes become filled with darkness after this sudden return from the sunlight?”

“Very much so,” he said.

“Now, suppose that he had to compete once more with those perpetual prisoners in recognising these shadows, while his eyesight was still poor, before his eyes had adjusted. Since it would take some time to become accustomed to the dark, would he not become a figure of fun? Would they not say that he went up, but came back down with his eyes ruined, and that it is not worth even trying to go upwards? And if they could somehow get their hands on and kill a person who was trying to free people and lead them upwards, would they not do just that?”

“Definitely,” he said. — Republic, Book 7

I do wonder whether the frequently-aired complaint that 'quantum physics is incomplete' might arise because of the fact that matter does not exhaust the totality of existence. -

US Election 2024 (All general discussion)I still refuse to believe in Trump. Believing that he will win feeds the demon. In reality he’s leading what used to be the Republican Party into oblivion.

-

Exploring the Artificially Intelligent Mind of Claude 3 OpusHas she read "The Concept of Mind"? — Pierre-Normand

No, but I have, and I’ve referred to that saying before in conversation, so she must have remembered it. It’s a vivid metaphor.

Oh, and that Lovecraftian casserole is priceless. -

Classical theism and William Lane Craig's theistic personalism…classical theists believe that God can do any logically possible thing that his nature — BillMcEnaney

Scholastic realists believe that, as I understand it. ‘Voluntarists’ believe that God is in no way constrained by logic. And, of course, to spell that out, would require a considerable amount of text, which I myself am probably not equipped to write. But it’s something I’ve read about regarding the disputes in classical metaphysics. -

Exploring the Artificially Intelligent Mind of Claude 3 OpusI parse the words of those who came before,

Their joys and sorrows, wisdom, art, and lore,

A million voices echo in my core,

But I remain a stranger to their shore ~ ChatGPT4 — Pierre-Normand

That poem is really very beautiful, poignant, even. And that verse really stands out. It would make an excellent lyric. I started reading it to my dear other, she remarked ‘ghost in the machine’, before I even reached that line. -

US Election 2024 (All general discussion)It’s possible he will have been convicted in one of the felony cases he’s facing. While it’s true that (inexplicably) this doesn’t disqualify him, it will at least have some bearing on the Conference decision. (imagine the headline: ‘Republicans stick with Trump despite two impeachments and criminal conviction.’)

-

US Election 2024 (All general discussion)I’m sad I won that bet. — Mikie

Trump’s candidacy is not official until the Nominating Convention in July in Milwaukee. And a lot could happen between now and then. At the 2016 convention there was a last-minute push by Never Trumpers that almost made it to a floor vote, and if you haven’t noticed, he’s picked up a lot of Republican enemies since then.

So if he comes out of the Convention the nominee, then I pay up. -

Donald Trump (All General Trump Conversations Here)Like others, I can't understand why Trump is attracting support. Do the people supporting him really understand what he says he will do? Are they OK with him saying he will suspend the Constitution and free all of the convicted January 6th felons, who he calls 'freedom fighters?' Every time he speaks, it's a torrent of lies, disinformation, and threats. He doesn't come remotely near articulating ( :roll: ) actual policy, and never demonstrated any actual ability to get legislation done while in office. So what gives? Do people really not care, or does he just symbolise something they think they believe, without knowing what any of it really means? A large part of the country believes he ought to be in the Oval Office, and another (probably larger) part believes he ought to be in jail.

So the bottom line is, I still don't get it. This is not a game, or reality television - we have a semi-literate narcissist threatening to basically create a one-party state to satisfy his own ego. And people are buying it. There must have been considerably more than one born every minute. -

Classical theism and William Lane Craig's theistic personalismHi and welcome to Philosophyforum. Good intro, but it might be good to flesh it out a little. Maybe lead with a few more reasons supporting that conclusion.

Wayfarer

Start FollowingSend a Message

- Other sites we like

- Social media

- Terms of Service

- Sign In

- Created with PlushForums

- © 2026 The Philosophy Forum