Comments

-

Direct realism about perceptionI don’t doubt we view things from a certain place in space and time. I just doubt that we’re watching things occur in our skull. — NOS4A2

We aren't watching things occur in our skull, just as when we feel pain we aren't touching something that occurs in our skull. You're misinterpreting the grammar. -

Direct realism about perceptionthat we are in fact seeing the environment. — NOS4A2

Which means what?

Without reference to first-person experience, how do you even make sense of what it means for an organism to "see" distant objects? According to your eliminative materialism there is just a mass of skin and bones and muscles reacting to other material that comes into immediate physical contact with it. -

Direct realism about perception

There is a biological organism with photoreceptor cells in the eye that absorb electromagnetic radiation and in doing so reduce the release of glutamate into the central nervous system, changing the behaviour of the neurons in the visual cortex, and in many cases affecting bodily movement.

What does it mean to say that this biological organism "directly sees" some object located 100m away from it? -

Direct realism about perceptionAn indirect realist speaks of the thing out there X and the thing in your head Y. If you are not committed to X resembling Y in any way (having no primary consistent quality), then why are we talking about Xs at all? — Hanover

Because we are not idealists and we believe that there is an X and that it has properties that are causally responsible for Y.

Do you think that is my argument though? — Hanover

If your argument is an argument against my claims then it must be — and you have presented it as an argument against my claims.

So if you don't deny that words like "headache" and "colour" are referring to the phenomenal character of subjective experiences then why do you keep bringing up Wittgenstein and Austin when I am clearly talking about perception and indirect realism? -

Direct realism about perceptionI said reference to mental states does not provide a method to determine meaning because they are not publicaly confirmable. — Hanover

They don't need to be publicly confirmable. I don't need you to tell me that I have a headache for me to have a headache, or for the word "headache" to refer to this mental state that I am in. -

Direct realism about perception

What you have been saying is that meaning is use and that mental states have nothing to do with it, and this is wrong. Some words and phrases do in fact refer to mental states, e.g. "mental states", "pain", and "red".

You also seem to have been saying that meaning-as-use entails direct realism, and this is also wrong. Perception and language are two different things. -

Direct realism about perceptionThis comment inadvertently makes my point. Wittgenstein and Austin are fairly clear that their object is to delineate the scope of philosophical inquiry. If ever you believe that scientific evidence defeats philosophical claims, then there has been a category error, confusing science with philosophy. The purpose of philosophy under this tradition is to preserve cogent argumentation and use of language and communication. So, if you are doing science, then your debate would be among scientists. That is, stop trying to disprove my position with science. My position makes no important scientific claims. — Hanover

Philosophical enquiry ought take into consideration what science says about the world. If science says that colours are "in the head" then our philosophical account of language ought recognise that the word "colours" refers to something "in the head", else it is a false account of language.

This doesn't contradict your prior comment, but it presents an odd result. You claim that science answers the questions about how we perceive and not philosophers, but you then claim Locke got it right. We'd have to chalk that up to luck and science vindicating his method, which was just armchair theorizing. That is, he was right, but for the wrong reason. — Hanover

I said that empirical study trumps armchair theorising, i.e. that if the two are ever in conflict then we ought accept the results of empirical study over the results of armchair theorising. I didn't say that armchair theorising can't be correct.

That does not provide support for Locke's theory. Locke posited two things: (1) Primary and (2) secondary qualities. Showing that color (a secondary quality) doesn't exist in the object doesn't prove that primary qualities (shape and size, for example) do. To stick to the science, we would show that none of the attributes of the object go unmediated by the subject, which means that I have no more reason to think a red ball is red than I do to think it's round. — Hanover

I only said that I agree that there is a distinction between primary qualities and secondary qualities, not that I agreed that all the things that Locke says are primary qualities are primary qualities and that all the things that Locke says are secondary qualities are secondary qualities. I agree with him that things like colours and tastes and smells are secondary qualities, but I don't necessarily agree with him that things like shape and size are primary qualities — and in fact I have made arguments earlier in this discussion that orientation is a secondary quality. But I'm not an idealist, and so I do believe that there are mind-independent objects and that they do have mind-independent properties. I'm undecided on whether to be a full Kantian and claim that primary qualities are unknowable or to be a scientific realist and claim that the Standard Model describes these primary qualities.

What I mean is that I use the term ship is a certain way and we get along with its use in predictable ways and I'm not entering into your theoretical scientific musings about reality. — Hanover

You can use the word "ship" however you like, but that has nothing to do with perception. Perception has nothing to do with language and everything to do with physics, physiology, phenomenology, and the relationship between experience and the mind-independent world. People and animals without a language either do or do not directly perceive the world, and whether or not they do is something that only science can answer, not a critical analysis of speech and writing. -

Direct realism about perception... unless you buy into primary and secondary qualities — Hanover

I do.

When I look at the photo of the dress I see a white and gold dress, when others look at the photo of the dress they see a black and blue dress. This is explained by us having different phenomenal experiences and the words "white", "gold", "black", and "blue" referring to the differing characteristics of these phenomenal experiences.

This view is supported by the science of colour:

One of the major problems with color has to do with fitting what we seem to know about colors into what science (not only physics but the science of color vision) tells us about physical bodies and their qualities. It is this problem that historically has led the major physicists who have thought about color, to hold the view that physical objects do not actually have the colors we ordinarily and naturally take objects to possess. Oceans and skies are not blue in the way that we naively think, nor are apples red (nor green). Colors of that kind, it is believed, have no place in the physical account of the world that has developed from the sixteenth century to this century.

Not only does the scientific mainstream tradition conflict with the common-sense understanding of color in this way, but as well, the scientific tradition contains a very counter-intuitive conception of color. There is, to illustrate, the celebrated remark by David Hume:

"Sounds, colors, heat and cold, according to modern philosophy are not qualities in objects, but perceptions in the mind." (Hume 1738: Bk III, part I, Sect. 1 [1911: 177]; Bk I, IV, IV [1911: 216])

Physicists who have subscribed to this doctrine include the luminaries: Galileo, Boyle, Descartes, Newton, Thomas Young, Maxwell and Hermann von Helmholtz. Maxwell, for example, wrote:

"It seems almost a truism to say that color is a sensation; and yet Young, by honestly recognizing this elementary truth, established the first consistent theory of color." (Maxwell 1871: 13 [1970: 75])

This combination of eliminativism—the view that physical objects do not have colors, at least in a crucial sense—and subjectivism—the view that color is a subjective quality—is not merely of historical interest. It is held by many contemporary experts and authorities on color, e.g., Zeki 1983, Land 1983, and Kuehni 1997. Palmer, a leading psychologist and cognitive scientist, writes:

"People universally believe that objects look colored because they are colored, just as we experience them. The sky looks blue because it is blue, grass looks green because it is green, and blood looks red because it is red. As surprising as it may seem, these beliefs are fundamentally mistaken. Neither objects nor lights are actually “colored” in anything like the way we experience them. Rather, color is a psychological property of our visual experiences when we look at objects and lights, not a physical property of those objects or lights. The colors we see are based on physical properties of objects and lights that cause us to see them as colored, to be sure, but these physical properties are different in important ways from the colors we perceive." (Palmer 1999: 95)

Empirical study trumps armchair theorising, which is why I take the science to prove that this ordinary language philosophy is wrong (at least as you are presenting it), and not the other way around.

Why not obtain meaning just from use without concern over the metaphysical underwriting of the term? — Hanover

Because it would be false. Phenomenal experience does in fact exist and some of our words do in fact refer to it and its qualities. All you seem to be saying is "let's pretend otherwise".

But it's confusing because you do seem to accept that the term "phenomenal experience" refers to phenomenal experience, and maybe also the word "pain"? So what exactly are you arguing? Just that colours are mind-independent in a way that pains aren't? What about tastes and smells? -

Direct realism about perceptionSo you are a direct realist with regard to ships? — Hanover

No, I'm saying that the word "ships" refers to ships. Perception and language are not the same thing.

Are you arguing every word has a referent? — Hanover

No, I'm arguing that some words and phrases refer to internal mental states, like "pain", "red", and "internal mental states". -

Direct realism about perceptionI'm not sure where that leaves us. — Esse Quam Videri

Neither do I, but thanks for the discussion. I don't know if we can avoid going around in circles at this point so perhaps best to end it here. -

Direct realism about perception

I was talking about colour and Wittgenstein's beetle, not ships. You seem to be reading more into my comments than was meant. I'm not saying that all words refer to internal mental states; I'm denying your claim that no words refer to internal mental states.

If the thing in your box is replaced with a cat then you wouldn't say "this cat is a beetle"; you'd say "my beetle has been replaced with a cat".

If I rewire your brain such that the same wavelengths of light stimulate different neurons then you wouldn't continue to say "the strawberry is red"; you'd say "the strawberry is now blue", and then be confused when nobody agrees with you.

And, most obviously, the term "internal mental states" refers to internal mental states.

The word "ships" still refers to the mind-independent ships in our shared world, even if it's possible that how they look to me is nothing like how they look to you. -

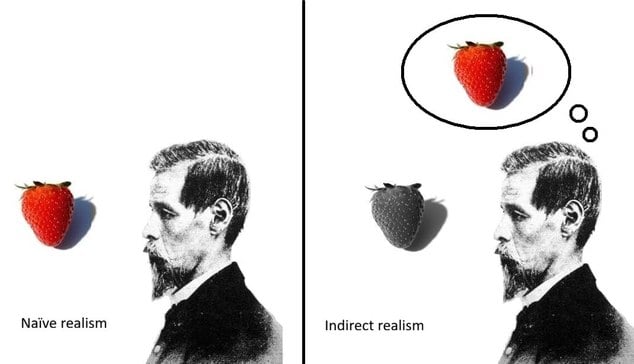

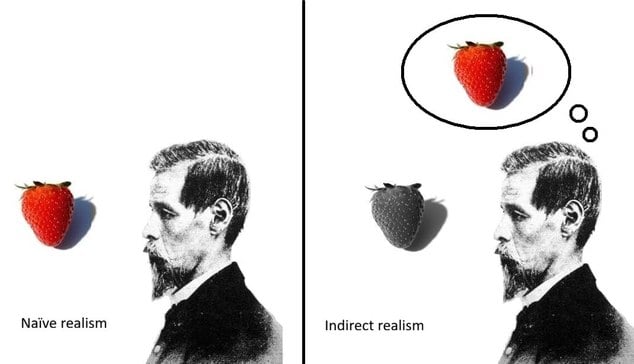

Direct realism about perception

I don't think I can explain it any simpler than this picture. With naive realism, experience isn't a mental phenomenon that occurs in the head; it's an "openness to the world" (McDowell, 1994) with distal objects being literal constituents of the experience and these objects being literally coloured in the sui generis sense. It's the way children and uneducated adults intuitively think of perception and the world (hence the term "naive"). Whereas with indirect realism experience is a mental phenomenon that occurs in the head, causally determined by proximal and distal stimuli but wholly separate to them, and with secondary qualities such as colour only being properties of this mental phenomenon. It's the way physics and physiology and neuroscience tells us perception and the world works.

-

Direct realism about perception(1) Rejected because it reifies experiential data into mental objects.

(2) Rejected because experience is not object-presentation.

(3) Rejected because the ontology and the inference both misdescribe consciousness.

(4) Rejected because experience is not object-presentation, whether distal or proximal. — Esse Quam Videri

I think you're reading too much into the word "object" — and note that I didn't even use the word "object" in the context of mental phenomena. Whatever pain is, it is a literal constituent of phenomenal experience, unlike the fire that is causally responsible for this phenomenal experience by burning the nerve endings in my skin.

(5) Rejected because it misdefines perception at the wrong level of analysis. — Esse Quam Videri

It's unclear what you mean here.

Are you saying that direct and indirect realists are using the word "perception" wrong? What counts as the "right" use? Why not just interpret it, as I've suggested earlier, as them using the word "perception" to mean one thing and you using the word "perception" to mean another thing? So perception is indirect according to what they mean by the word "perception" (and the word "indirect") and direct according to what you mean by the word "perception" (and the word "direct")?

Or are you saying that direct and indirect realists are using the word "perception" (and the words "direct" and "indirect") in the same way that you but are wrong about what would satisfy "direct perception" and about what would satisfy "indirect perception"?

I am asking about the epistemic relationship between the two. — Esse Quam Videri

I don't know how to answer that. What is the epistemic relationship between the words I'm reading and World War II, or between the radio I'm listening to and the distant events being reported on? The brain and/or mind is somehow able to interpret visual and auditory sensations into a meaningful experience that brings about understanding of and/or intentionality towards other things. As I asked Hanover, why does it matter if we move the line further back "into the head"? Mental phenomena, whatever they are, are as real as anything else in the world and we can extrapolate from them as well as we can extrapolate from vibrations in the air.

On this view, what is the difference between a white-circle "manifesting" itself within experience and a boat "manifesting" itself in experience? — Esse Quam Videri

For there to be a token identity between the features of the experience and the features of the thing experienced. I believe something I said earlier in the discussion is relevant here:

The direct realist argues that a) the boat appears blue because b) the boat is blue and c) the boat is manifested in experience.

The meaning of the term "manifested" is such that if (a) and (c) are true then (b) is true, and if (b) and (c) are true then (a) is true — and not just according to any interpretation of (b) but according to the specific interpretation that qualifies as naive colour primitivism. -

Direct realism about perceptionAren't you asking what difference any of this makes? As in, if I think even to another extreme that we live in the matrix and we're all hooked up in pods and none of this is real, we're still going about this conversation just the same. That is, it'd be the same with direct realism, indirect realism, idealism, and evil genius land.

And that's the Austin approach. Why all the complicated explanations and not just say WYSIWYG? — Hanover

Because we're interested in how perception and the world actually works. As I said before, Austin and Wittgenstein aren't "deflating" philosophy, they just seem to be refusing to do philosophy — at least as you and Banno are presenting them. They're welcome not to, but that doesn't suffice as a refutation of those who do. -

Direct realism about perceptionI believe this is where we keep talking past each other. I reject the above. — Esse Quam Videri

Reject what specifically?

1. That colours and pain are mental phenomena

2. That colours and pain are directly present to the mind in phenomenal experience

3. The transitive law that therefore mental phenomena are directly present to the mind in phenomenal experience

4. That distal objects are not directly present to the mind in phenomenal experience

5. That the phrase "to directly perceive X" as used by traditional direct and indirect realists means "X is directly present to the mind in phenomenal experience"

Out of curiosity, for the indirect realist described above, what is the relationship between multi-modal sensory data (redness as-seen, loudness as-heard, etc.) and the judgement that expresses the claim “that’s a truck”? — Esse Quam Videri

Are you asking about the binding problem? We don't have a good explanation of that yet.

Also, what does it mean to say that multi-modal sense data are “directly present” to the mind? — Esse Quam Videri

That this sense data is a literal constituent of phenomenal experience. Taken from the problem of perception, "the character of your experience is explained by an actual instance of [a white circle] manifesting itself in experience". This is something that both direct (naive) and indirect realists believe, but with direct (naive) realists believing that this circle is a mind-independent object and its whiteness is a mind-independent property and indirect realists believing that this white circle is a mental phenomenon (e.g. of the kind that also occurs during hallucinations and dreams), (usually) caused by but wholly separate to the mind-independent object and its properties. -

Direct realism about perceptionSecond, in the traditional debate both direct and indirect realists assume that some kind of object is directly present to the mind through phenomenal experience, whether worldly or intermediary. I reject that assumption. — Esse Quam Videri

Then we return back to something I said earlier:

1. Distal objects are directly present to the mind in phenomenal experience

2. Mental phenomena are directly present to the mind in phenomenal experience

Traditional direct realists believe that (1) is true and (2) is false, traditional indirect realists believe that (1) is false and (2) is true, and you believe that both (1) and (2) are false.

The first thing to note is that according to what traditional direct and indirect realists mean by the phrase "direct perception", perception of distal objects is direct if and only if (1) is true and perception of distal objects is indirect if and only if (1) is false. As such, according to what these groups mean by the phrase "indirect perception", perception of distal objects can be indirect even if (2) is false. Therefore, if you accept that (1) is false then your position is consistent with the "weaker" indirect realist claim that (1) is false even if inconsistent with the "stronger" indirect realist claim that (2) is true.

The second thing to note is that (2) does not require that mental phenomena be "objects" in the sense that I think you mean by the word. To be the object of perception isn't to be some thing with extension and mass or anything like that; to be the object of perception is to be the X in "I experience X", at least as I understand it. If I feel pain then pain is the object of perception, if I see colours then colours are the object of perception, if I hear a truck then a truck is the object of perception, and so on. The indirect realist's claim is that pain and colours are mental phenomena and are directly present to the mind in phenomenal experience, whereas a truck is a machine that exists at a distance from the body and is not directly present to the mind in phenomenal experience, and so therefore perception of mental phenomena is direct and perception of trucks is not direct (is indirect) — with perception of trucks only made possible by the perception of mental phenomena. -

Direct realism about perception

I don't really understand your questions. You and I are having a successful(ish) conversation right now despite the fact that neither of us is directly perceiving the same thing; even the direct realist must accept this. I can talk about your post and you can talk about my post but what do each of us directly perceive? The direct realist will say that you directly see your computer screen and that I directly see my computer screen. We might assume that our screens resemble each other but maybe they don't. Perhaps I don't even have a screen and instead I have some device that speaks the words out to me in French because I'm blind and French. And we can even talk about one another despite having never met and despite neither of us having anything to do with the computer screens we're looking at or the audio being spoken (other than in the causal sense).

If all of this is possible then why is it so problematic to just move things back "into the head"? You accept the existence of internal states, and internal states are as real as anything else in the universe, even if we cannot in practice perceive one another's. But then in practice we do not perceive each other or one another's computer screens but that's no problem at all. So what difference does it make if our conversation is only possible through the direct perception of our own internal states rather than the direct perception of our own computer screens or audio devices? -

The Strange case of US annexation of Greenland and the Post US security structureNow he's trying to blackmail Europe into selling him Greenland. Utterly absurd.

-

Donald Trump (All Trump Conversations Here)I bet Trump thinks that possessing the medal is the same as being awarded the prize. It's like buying a trophy off eBay.

-

Direct realism about perceptionAnswering that question will involve analyzing the agent's behavior to determine what it is referring to when it makes claims about the world. — Esse Quam Videri

Once again, this shows that you are arguing for semantic direct realism, which is distinct from phenomenological direct realism and compatible with phenomenological indirect realism.

The traditional dispute between direct and indirect realism has nothing to do with whether or not our claims are about the world and everything to do with whether or not the world is "directly present" to the mind in phenomenal experience. It's an issue that covers even those unintelligent agents who don't have a language and so don't make claims of any kind, e.g. babies and animals.

You're saying that the painting is of Obama and that the book is about Trump and indirect realists are saying that the painting is just paint and that the book is just words and that neither Obama nor Trump are "directly present". And your responses are akin to arguing "but it's not a painting of paint and it's not a book about words".

So rather than the traditional dispute being "framed wrong" as you asserted before, it's just that you mean something entirely else by the phrase "direct perception". According to what traditional direct and indirect realists mean by the phrase, it's clear that the traditional direct realists are wrong and indirect realists are right, which is why "indirect perceptual realism is broadly equivalent to the scientific view of perception". -

Direct realism about perceptionI know that's what you want to conclude, but your thought experiment doesn't show that. What it shows is you've figured out how to change what people say. If your experiment is scientific, you can only report your measurable results. If I stimulate a monkey's brain to make him smile, my report will be that he smiled, not that I made him happy. — Hanover

I can perform the experiment on myself. I first stimulate neuron A and then neuron B and note that I have two different colour experiences. I then rewire my brain such that the light that previously triggered neuron A now triggers neuron B and the light that previously triggered neuron B now triggers neuron A. I shine the two lights into my eyes and note that the colour I experience continues to correlate with the previous neural activity but not with the previous wavelength of light, i.e. that 700nm light now causes me to see blue because it triggers neuron B and that 450nm light now causes me to see red because it triggers neuron A.

I then assume that I'm not special and that other humans have first-person experiences like mine and aren't just p-zombies, and that when I perform this experiment on them their choice of words is determined by the phenomenal character of their experience and not because they're automatons whose language-programming has been altered. Of course maybe this assumption is false, and that the reason my argument makes sense to me but not to you is because I'm not a p-zombie and you are, in which case we have a useful means to test whether or not someone is a p-zombie; those who agree with me aren't and those who don't agree with me are.

I have no idea what's in your mind and you have no idea what's outside the mind, so we limit it to what we can talk about. — Hanover

You don't need to know what's in my mind. You just need to understand that if the beetle in your box was replaced with a cat then you wouldn't say "this cat is a beetle"; you'd say "there is no longer a beetle in my box but a cat instead". You then perform the quite easy task of recognizing that other people are probably much like you, and would say much the same thing if their beetle was replaced with a cat. You don't need to literally read someone's mind to "put yourself in their shoes". -

Direct realism about perceptionIn (1), the visor is not itself the object of intentionality. It is part of the causal infrastructure that realizes intentionality.

In (2), the visor is itself the object of intentionality. The subject’s perceptual state is about what the visor presents. — Esse Quam Videri

Why? You're just begging the question again. I'll respond by saying that in (2) the strawberry is the object of intentionality and the visor is part of the causal infrastructure that realizes the intentionality. Where do we go from there? -

Direct realism about perceptionJim and John could still see the exact color before and after rewiring but they say different words now. — Hanover

Jim now uses the word "blue" when a 1nm light shines in his eyes because his experience has changed. After rewiring his brain 1nm light appears different to how it appeared before. It wasn't just some random, spontaneous, unexplained decision to use a different word to describe the same experience. -

Direct realism about perceptionWhat would happen if we changed your beetle to a cat and now you said "cat" for beetles — Hanover

I wouldn't. I'd say "there's a cat in my box, not a beetle".

but the point is it doesn't matter and we can't know — Hanover

It does matter even if we can't know. Something like the inverted spectrum hypothesis and indirect realism can't be handwaved away by arguing that we can't know if what you are referring to by the word "red" is the same thing that I am referring to by the word "red". Pretending that the word's meaning only has something to do with public behavior because it's the only thing of practical relevance in everyday life isn't "deflating" philosophy but refusing to do philosophy. You're welcome not to, but it doesn't work as a refutation of those who want to address issues of phenomenology and metaphysics. -

Direct realism about perceptionHe denies it's relevance for communication and meaning — Hanover

Irrelevant for communication but not irrelevant for meaning. That's why the people wearing visors ask "why is the sky now green and why is the grass now red?" after their private screens are reprogrammed and why Jim says "1nm light now appears blue" after his brain is rewired.

Despite the public use of the word "beetle" it really does refer to the private thing in the box. If through magic or advanced technology you were to replace the contents of my box with something very different then I wouldn’t recognize it as being a beetle. -

Direct realism about perceptionI like Wittgenstein's approach better where meaning falls to use, making the swirl in your head irrelevant. — Hanover

This is a somewhat ambiguous claim. It's certainly practically irrelevant if the phenomenal character I experience when my eyes are stimulated by 700nm light is the same or different to the phenomenal character you experience when your eyes are stimulated by 700nm light, but it doesn't then follow that colour terms don't (also) refer to this phenomenal character. I believe I showed that it can and does in the section below the image here and in the post here. -

Direct realism about perception

Hallucinations are not delusions; they're not belief-like but experiential and with phenomenal character. When I eat shrooms I very much experience and am very much aware of the kaleidoscope of colours that I am seeing (and very much know that the colours I am seeing are an hallucination caused by the fungus).

If you're going to define "experience of" and "aware of" in such a way that nothing is experienced and we're not aware of anything when we dream and hallucinate then it's no surprise that your understanding of indirect realism is a misrepresentation. Feeling pain isn't like feeling a table but it's still the experience and awareness of something. The grammar of the first doesn't entail touching something with one's hands even if the latter does. -

Direct realism about perception

So what is the relevant difference between:

1. People born without eyes and born wearing a visor that discharges electricity into their optic nerve

2. People born with eyes and born wearing a visor that discharges electromagnetism into their eyes which discharges electricity into their optic nerve

My issue is that you appear to argue that (1) is direct perception because they don't have to assess the veracity of the visor's output but that (2) is indirect perception because they do have to assess the veracity of the visor's output, but there appears neither a causal nor a normative justification for this inconsistency. Either they are both direct perception or they are both indirect perception. -

Direct realism about perception

Neuron A correlates to one colour experience and neuron B correlates to another colour experience, tested by directly stimulating neuron A and then neuron B and asking the subject if they see the same, different, or no colours, and them confirming that they see two different colours.

In (1) John's eye reacts to the 700nm light by stimulating neuron A via the optic nerve into the brain.

In (2) Jane's eye reacts to the 700nm light by stimulating neuron B via the optic nerve into the brain.

In (3) the visor reacts to the 700nm light by emitting 450nm light, and John's eye reacts to the 450nm light by stimulating neuron B via the optic nerve into the brain.

In (4) the visor reacts to the 700nm light by stimulating neuron B via a wire into John's brain. -

Direct realism about perception

I don't understand what you mean by saying that the standard is normative. If you just mean that my perception is direct if this is what I normally see in such a situation then the people born wearing visors with a screen on the inside have direct perception of the world beyond the visor, because that it is how they normally see the world. They ought no more assess the "veracity" of the visor's output than they ought if they didn't have eyes and the visors interfaced directly with their brain. This is where I think you're guilty of special pleading, or moving the goalpost. Either the former is direct perception or the latter isn't. -

Direct realism about perception

What determines whether or not (4) counts as replacement or as intervention?

If it helps, as it's pertinent to real life, all scenarios are fixed at birth.

1. Only eyes with eyes into brain

2. Only visor with visor into brain

3. Both eyes and visor, with visor bypassing eyes into brain

4. Both eyes and visor, with eyes bypassing visor into brain

5. Both eyes and visor, with visor into eyes into brain

6. Both eyes and visor, with eyes into visor into brain

Which count as direct perception and which count as indirect perception? -

Direct realism about perceptionIf the visor genuinely bypasses the eyes and wholly replaces them as the system that fixes perceptual correctness for the subject, then yes, in that revised scenario, perception would be direct relative to the visor. But that is no longer the original (4). — Esse Quam Videri

It is the original (4)?

4. The strawberry reflects 700nm light into a visor and the visor bypasses John's eye to stimulate his B neuron, causing him to "see blue".

Compare with:

5. The strawberry reflects 700nm light into John's eye and his eye bypasses the visor to stimulate his A neuron, causing him to "see red".

(5) is direct perception if and only if (4) is direct perception, and above you argued that (5) is direct perception. -

Direct realism about perceptionSo if a subject initially has only the visor, then perception is direct relative to the visor. If the subject later acquires eyes that bypass the visor, then the eyes now constitute the perceptual capacity instead. — Esse Quam Videri

Then referring back to this post, do you now accept that (1) is direct perception if and only if (4) is direct perception? Because to rephrase the quote above: if a subject initially has only eyes, then perception is direct relative to the eyes, but if the subject later acquires a visor that bypass the eyes then the visor now constitutes the perceptual capacity instead. -

Direct realism about perceptionWe can coherently say: the visor is causing the subject to see the strawberry as blue even though, absent that device, it would appear red to that very same subject. — Esse Quam Videri

Let's assume that the people who wear the visor don't have eyes, and so absent their visor they don't see anything.

Let's also assume that they are later given eyes, and that rather than their visor bypassing their eyes to stimulate their optic nerve, their eyes bypass their visor. We can coherently say: the eyes are causing the subject to see the strawberry as red even though, absent the eyes, it would appear blue to that very same subject.

So why do eyes count as part of direct perception but the visor doesn't? -

Direct realism about perceptionThe visor’s outputs purport to stand in for how the environment is perceptually available independently of it — Esse Quam Videri

The visor doesn't purport to do anything. It's just a machine that deterministically reacts to light, exactly like an organic eye.

If it helps, the visor was not designed by anyone for any purpose. It spontaneously formed via quantum fluctuations, and those who wear it don't even know that they wear it. -

Direct realism about perceptionWhat is a mystery is the nature of the stimulation of John’s B neuron. What we understand is the emission of 450 nm light which we typically call “Blue” is associated with stimulation of John’s B neuron. And no other color’s wavelength should be stimulating this color. So, if it cannot be no other color wavelength stimulating this color, other than blue, what is the nature of this stimulation? We are alway bombarded with enormous amount of “stimulations” from the external world that can make color judgments difficult to get accurate. Looks like the visor is one of them. — Richard B

I don't quite understand your question.

In this simplified account of physics and physiology, when the sense receptors in John's eye detects 450nm light it sends an electrical signal up the optic nerve and into the brain, "activating" neuron B, and when the sensors on the visor detect 700nm light it sends an electrical signal up the optic nerve and into the brain, "activating" neuron B. -

Direct realism about perceptionIn (2), Jane’s visual system—eye, retina, and downstream neural processing—constitutes her perceptual capacities. Whatever the mapping from wavelength to neural state happens to be (even under inversion), that mapping is not something that stands in for perception; it is how objects are perceptually available to her. There is no further question of whether this mapping is “doing its job correctly,” because it is not functioning as an intermediary whose output purports to represent the environment. It defines what counts as seeing for Jane.

By contrast, in (4), the visor introduces a mapping that is not constitutive in this sense. Even if it covaries lawfully with the strawberry, it functions as a substitutable system that fixes perceptual outcomes independently of the strawberry’s own role in determining how it is perceived. That mapping could be changed, replaced, recalibrated, or removed without thereby redefining what it is for John to perceive at all. That is why it is intelligible to ask whether the visor is presenting the environment correctly. The mapping is instrumental rather than constitutive, and so its outputs are assessable as succeeding or failing as presentations of the world. — Esse Quam Videri

I'm sorry but this still seems to beg the question. You just assert that Jane's organic eye counts as constituting her perceptual capacities and that John's bionic eye doesn't. I want to know why this is. Why does a bionic eye "function as an intermediary whose output purports to represent the environment and can be assessed as succeeding or failing" but an organic eye doesn't? They both function in identical ways; they react to electromagnetic stimulation by generating neurotransmitters that are sent up the optic nerve. It shouldn't matter whether the eye is one's natural eye, taken from a donor, grown in a lab, built by a mechanical engineer, or is a Boltzmann eye that spontaneously formed from quantum fluctuations. If any one of them can output the "wrong" neurotransmitters given the input then all of them can.

Although it's still not clear to me what would even count as the "wrong" (or the "right") neurotransmitters given your objection to the notion that the phenomenal character of experience can "succeed" or "fail" at representing the mind-independent nature of the world. It seems like your position now depends on the very naive realism that you previously rejected. -

Direct realism about perceptionIn (4), by contrast, the visor is not functioning as part of the subject’s perceptual system in that sense. — Esse Quam Videri

Why not? It is effectively a bionic eye, and you granted before that a bionic eye is no different in kind to an organic eye. There's nothing privileged about proteins. Both just deterministically react to electromagnetism by sending neurotransmitters up the optic nerve. So to suggest that (4) is different to (2) is special pleading or begging the question. A bionic eye "intervenes" and could "fail to present the environment" if and only if an organic eye "intervenes" and could "fail to present the environment". -

Direct realism about perception@Esse Quam Videri, I'll try to explain this in an even simpler way, using a very simplified account of physics and physiology.

1. The strawberry reflects 700nm light into John's eye and John's eye stimulates his A neuron, causing him to "see red".

2. The strawberry reflects 700nm light into Jane's eye and Jane's eye stimulates her B neuron, causing her to "see blue".

3. The strawberry reflects 700nm light into a visor that emits 450nm light into John's eye and John's eye stimulates his B neuron, causing him to "see blue".

4. The strawberry reflects 700nm light into a visor and the visor bypasses John's eye to stimulate his B neuron, causing him to "see blue".

You count (1) and (2) as direct perception and (3) as indirect perception, but what about (4)?

If the visor's "output" in (4) — i.e. stimulating John's B neuron — can be a "false" presentation of the strawberry then surely the eye's "output" in (2) — i.e. stimulating Jane's B neuron — can also be a "false" presentation of the strawberry. So it seems to me that (2) is direct perception if and only if (4) is direct perception.

But if (4) is direct perception then why isn't (3)? It seems to me that the visor in (3) can "fail" to present the strawberry if and only if the visor in (4) can "fail" to present the strawberry. So it seems to me that (4) is direct perception if and only if (3) is direct perception.

And because (1) is direct perception if and only if (2) is direct perception it seems to me that (1) is direct perception if and only if (3) is direct perception. -

Direct realism about perceptionIt is that we do not perceive the outputs of retinal processing and then perceive the world by way of them; we perceive the world through the eye. By contrast, the visor produces an image that is itself an object of visual experience—something we see, and which purports to show us the scene beyond. — Esse Quam Videri

Let's assume that there are just five "things" in the world; my brain, my eye, the visor, light, and a strawberry. The strawberry "moves" the light which "moves" the visor which "moves" the eye which "moves" the brain.

Without begging the question, why is it correct to say that we perceive the strawberry "through" the eye and not that we perceive the strawberry "through" the visor or "through" both the eye and the visor? You said before that it depends on whether or not something "introduces a layer whose outputs can succeed or fail as presentations of the environment". So why is it that the visor's output can "fail" as a presentation of the strawberry but that the eye's output cannot "fail" as a presentation of the visor? Remember; neither the visor nor the eye "purport" to do anything. They just behave according to the deterministic laws of physics. We make true or false judgements that something "succeeds" or "fails", but that's subsequent to perception and phenomenal experience.

Michael

Start FollowingSend a Message

- Other sites we like

- Social media

- Terms of Service

- Sign In

- Created with PlushForums

- © 2026 The Philosophy Forum