Comments

-

Is there an external material world ?Excellent interview with the founder of QBism here.

Philip Ball on why the many worlds interpretation sucks.

Bernard D'Espagnat says what we call reality is just a state of mind.

The only definite fact in all of this is that quantum physics undermines realism. -

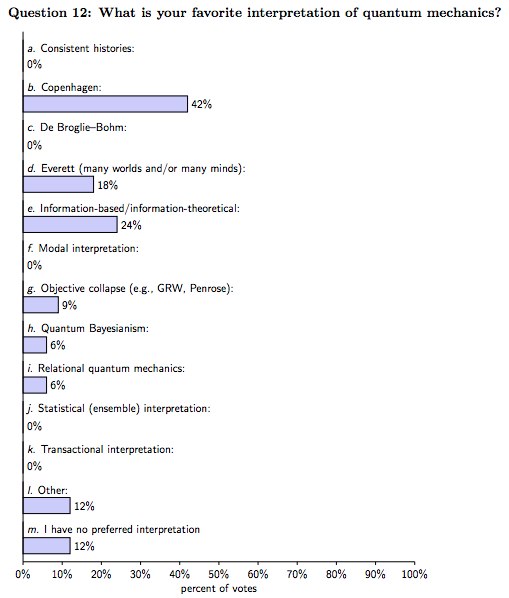

Is there an external material world ?Poll carried out by Maximilian Schlosshauer, Johannes Kofler, and Anton Zeilinger at a quantum foundations meeting. The pollsters asked a variety of questions which were patiently answered by the 33 participants. Here are the results:

From here. -

Is there an external material world ?What's going on here? — Isaac

Hey thanks for taking the trouble to find all those quotes, but I don't really understand what you're asking. What I'm arguing in all of those is that quantum physics has a tendency to undermine scientific realism. This is not news. There has been a lot of commentary and controversy about this point since the 1920's. So what's the question again? -

On whether what exists is determinateGlad to be not just another voice in the wilderness ;-)

-

On whether what exists is determinateAs you're seeing the point, I'll flesh out a bit more detail of where I'm up to in this quest. As we discussed, the status of mathematics - 'invented or discovered' - is an interesting philosophical conundrum. The typical modern view is that mathematics has to be a human invention, something that is created by us, for our purposes, because it can't see how the Universe has an innately mathematical structure.

There's an encyclopedia article I often refer to, The Indispensability Argument in the Philosophy of Mathematics, which is a useful summary of some of the main arguments. Briefly, it starts with reference to paper by a well-known math scholar, Paul Benacerraf, on the topic. According to this paper 'Standard readings of mathematical claims entail the existence of mathematical objects. But, our best epistemic theories seem to debar any knowledge of mathematical objects.'

What are these 'best epistemic theories' and why do they 'seem to debar' such knowledge? Reading on, we learn that:

Mathematical objects are in many ways unlike ordinary physical objects such as trees and cars. We learn about ordinary objects, at least in part, by using our senses. It is not obvious that we learn about mathematical objects this way. Indeed, it is difficult to see how we could use our senses to learn about mathematical objects. — IEP

So this is a hint that 'our best theories' are empiricist, namely, that knowledge is only acquired by sensory experience, and that there is no innate facility for knowledge, of the type that mathematical reasoning appears to consist in. The point is elaborated below.

Some philosophers, called rationalists, claim that we have a special, non-sensory capacity for understanding mathematical truths, a rational insight arising from pure thought. But, the rationalist’s claims appear incompatible with an understanding of human beings as physical creatures whose capacities for learning are exhausted by our physical bodies. — IEP

So, if the 'rationalist philosophers' are correct then we're not physical creatures whose capacities for learning are exhausted by our physical bodies! The horror! When 'our best theories' are all premised on the fact that we are! That's the motivation behind this whole argument. Because if number is real but it's not physical, then this defeats materialism, so it's acutely embarrasing for mainstream philosophy. Especially because the 'mathematicization of nature' has been so central to the ballyhoed advance of modern science (hence it's 'indispensability').

This lead me to look into why the faculty of reason was attributed with divine powers by Greek philosophy. Now there's a research topic for the ages. -

On whether what exists is determinate:up:

'nihil ultra ego'

"red jumper" reduces to an indexical such as this, which points directly without further linguistic mediation to the non-linguistic 'term' concerned. — sime

Interesting, but only speaks to the philosophical implications by way of analogy, I think. -

Is there an external material world ?Yet you've raised the apparent consequences of the double slit experiment in this very thread. Are you suggesting that wasn't an empirical observation? Or are you suggesting that, for example, a naive materialist need take no notice at all of that empirical result because empirical data need not constrain our metaphysics? Is materialism rescued after all? The main evidence thrown against it is from quantum physics. — Isaac

The debate over quantum physics is a debate over the meaning of the experiments. You can’t question what is observed - that is the empirical fact. But what it means is another matter. That’s the way in which quantum physics forced metaphysics back into the discourse. The naive materialist can completely ignore the question and just carry on using the method for his or her purposes - the attitude known as ‘shut up and calculate’. Quantum physics expertise is required for a huge range of disciplines and techniques nowadays, and many of those using it do exactly that. -

Is there an external material world ?All I'm trying to do here is bring what I know (cognitive science, psychology) to the discussion, together with the consequences I think that knowledge has for our options with regards to metaphysical positions. — Isaac

You do, and while I respect the discipline it often tends to be a pretty one-way street. It’s like ‘if you want to demonstrate the limitations of empiricism you’d better have darn good empirical evidence.’

Besides from an empirical pov the OP question is meaningless - it goes without saying that there’s an external material world (indeed someone started an OP on exactly that point.) Naturalism starts with the accepted reality of the sense-able domain, and from within that framework of course there’s an external material world. It’s only a meaningful question when you start to question what ‘material’ really means, or what ‘external’ really means. And that’s where metaphysical or meta-cognitive considerations come into play. That’s the sense in which it’s a philosophical question.

Of course we’re all subject to and influenced by the environment and circumstances. I’m not a cave-dwelling hermit. Where I started my philosophical quest was in pursuit of spiritual illumination. Strange as it seems, that used to be a real part of philosophy although it is long forgotten and now abandoned. But as I’m not a tenured academic with a publishing career I’m not obliged to conform with current intellectual fashion. But that’s the metaphysical thread I’m attempting to follow through the labyrinth. -

Evolution, creationism, etc?I like this quote from that article:

Haldane [in the 1930s] can be found remarking, ‘Teleology is like a mistress to a biologist: he cannot live without her but he’s unwilling to be seen with her in public.’ Today the mistress has become a lawfully wedded wife. Biologists no longer feel obligated to apologize for their use of teleological language; they flaunt it. The only concession which they make to its disreputable past is to rename it ‘teleonomy’. -

Is there an external material world ?I'm no expert on philosophy, not by a long way, but I don't think that my disagreeing with certain philosophical approaches is, alone, evidence that I've not understood them — Isaac

I don’t consider myself expert either, I did two two years of undergrad and have since read a bit. But I do know that it’s a different subject to cognitive science. -

Is there an external material world ?I don't see it as a competition, but as I've noted before, you look at the matter through an empiricist perspective, and you don't really see how it could be anything else - seems to me, anyway.

-

Evolution, creationism, etc?It was renamed (slightly revised) as teleonomy - apparent purpose.

-

Is there an external material world ?I don't see that as a positive for philosophy. — Isaac

Then again, you don't seem to hold philosophy in much esteem. -

Is there an external material world ?Are you suggesting that it can be deduced rationally that philosophers succeed at doing what they claim to do? That we can rationally determine that it a philosopher claims to study 'the unconditioned' that they succeed in that endeavour? — Isaac

They may not be successful, but that is what the purpose ought to be. (It is what the rationalist philosophers were all about!) Of course, as I've said, I recognise that in modern philosophy that is not at all the case, I have more in mind the traditional conception of philosophy up until the time of Descartes.

The unexamined preconceptions I'm referring to aren't matters of personal prejudice - they're the well-recognised assumptions of the scientific attitude of Galileo, Descartes, Newton, and the other founders of modern science. If you study philosophy of science (Kuhn, Feyerabend, Polanyi) it is the subject of considerable analysis. -

On whether what exists is determinatealthough I know it's controversial. — litewave

:up: If you get that, you're seeing the point.

If you would be so generous, what is the greatest criticism you've heard of the traditional view? I always assumed it was dismissed in our time, not because of any major deficieny in itself, but because of modern arrogance. — Merkwurdichliebe

You're not wrong! The roots go back to the disputes about universals in medieval times, between the scholastic realists (Aquinas and others) the nominalists (Ockham, Bacon) and then later the empiricists (who were mainly nominalist.) And history was written by the victors. All of it happened so long ago that collectively we've forgotten about it.

Thomists and other critics of Ockham have tended to present traditional realism, with its forms or natures, as the solution to the modern problem of knowledge. It seems to me that it does not quite get to the heart of the matter. A genuine realist should see “forms” not merely as a solution to a distinctly modern problem of knowledge, but as part of an alternative conception of knowledge, a conception that is not so much desired and awaiting defense, as forgotten and so no longer desired. Characterized by forms, reality had an intrinsic intelligibility, not just in each of its parts but as a whole. With forms as causes, there are interconnections between different parts of an intelligible world, indeed there are overlapping matrices of intelligibility in the world, making possible an ascent from the more particular, posterior, and mundane to the more universal, primary, and noble.

In short, the appeal to forms or natures does not just help account for the possibility of trustworthy access to facts, it makes possible a notion of wisdom, traditionally conceived as an ordering grasp of reality. Preoccupied with overcoming Cartesian skepticism, it often seems as if philosophy’s highest aspiration is merely to secure some veridical cognitive events. Rarely sought is a more robust goal: an authoritative and life-altering wisdom. — What's Wrong with Ockham, Joshua Hothschild

That essay is a good starting point, although by no means an easy read (it used to be posted online but the site is no more. (Unfortunately (or so it seems to me) this kind of critique is often associated with social conservatism, which I am not really comfortable with, but it's a matter of 'let the chips fall where they may'.)

The other book I found really helpful, I read pretty well straight after discovering philosophy forums, there's a very good reader review here. It's a revisionist history of how modernity got to be how it is. -

On whether what exists is determinateI am not using the word 'object' metaphorically but generally, as 'something' — litewave

It's too general a distinction for the purposes of philosophy. I agree that abstract objects are real, but many do not agree with that, on the basis that they have no concrete or objective existence. There is a difference between the sense in which the [tree/apple/chair] exists, and the sense in which prime numbers exist, because the latter can only be deduced by an act of counting and reasoning, not perceived by the senses. -

On whether what exists is determinateIt is this "union of knower with known" that is difficult for me because it insinuates a division (knower/known). — Merkwurdichliebe

There is an actual division, isn't there? When I see the proverbial [apple/tree/cup] then there's a distinction between the knowing subject and the known object, surely?

The way it is explained in terms of traditional realism (as I understand it) is that the senses apprehend the material thing, but the rational mind realises the form.

Knowledge presupposes some kind of union, because in order to become the thing which is known we must possess it, we must be identical with the object we know. But this possession of the object is not a physical possession of it. It is a possession of the form of the object, of that principle which makes the object to be what it is. This is what Aristotle means when he says that the soul in a way becomes all things. Entitatively the knower and object known remain what they are. But intentionally (cognitively) the knower becomes the object of his knowledge as he possesses the form of the object, That is why Aquinas says with reference to intellectual knowledge:

Intelligent beings are distinguished from non-intelligent beings in that the latter possess only their own form; whereas the intelligent being is naturally adapted to have also the form of some other thing; for the idea of the thing known is in the knower. — Summa

As expressed by a classics scholar:

Aristotle, in De Anima, argued that thinking in general (which includes knowledge as one kind of thinking) cannot be a property of a body; it cannot, as he put it, 'be blended with a body'. This is because in thinking, the intelligible object or form is present in the intellect, and thinking itself is the identification of the intellect with this intelligible. Among other things, this means that you could not think if materialism is true… . Thinking is not something that is, in principle, like sensing or perceiving; this is because thinking is a universalising activity. This is what this means: when you think, you see - mentally see - a form which could not, in principle, be identical with a particular - including a particular neurological element, a circuit, or a state of a circuit, or a synapse, and so on. This is so because the object of thinking is universal, or the mind is operating universally.

….the fact that in thinking, your mind is identical with the form that it thinks, means (for Aristotle and for all Platonists) that since the form 'thought' is detached from matter, 'mind' is immaterial too.

Lloyd Gerson, Platonism vs Naturalism, 39:00

I'm not saying I believe it but I'm very interested in understanding it, and also in understanding criticisms of it.

Is it as simple as saying humankind has a dual nature (appetitive and rational) which directly relates to the dual nature of reality (the perceptual and the intelligible)? — Merkwurdichliebe

Is that a simple thing to say? Besides, the two principles are generally described as sensible (sense-able) and intelligible, i.e. what can be apprehended by the senses and what can be known by the mind.

And, although they are objects in the metaphorical sense, they have literal existence in the same way a cup does. — Merkwurdichliebe

Ah, but do they? I'm saying that @litewave is glossing over the issue by saying that e.g. 'time and space are objects'. In fact, the nature of time and space are unresolved questions, and arguably not scientific questions at all. Time and space may be regarded as 'objects' (or parameters) for the purposes of mathematical physics but it doesn't make them objects in the literal sense. Same with other intelligible objects. Whereas most empirical philosophers will deny that they have any kind of existence except as mental acts. -

On whether what exists is determinateBut you're still using the term 'objects' metaphorically. Numbers, space-time, the wave equation - none of these are actually 'objects' in the literal sense.

Object 1. a material thing that can be seen and touched.

"he was dragging a large object"

2. a person or thing to which a specified action or feeling is directed.

"disease became the object of investigation"

They're objects in the sense of 'objects of thought' but they're not literally objects. -

Is there an external material world ?The only way to study anything at all, is to represent it as a phenomenon if it’s a real object, or as a conception if it’s an abstract object. But the human system, predicated on relations, can cognize nothing by a single representation, insofar as a single representation doesn’t have anything to which it relates. So to study a thought, considered as an abstract object in itself, and without regard to the content of it, it must be turned into a conception. How can we conceive of something that has no content? — Mww

:100: -

On whether what exists is determinatespacetimes are just a special kind of objects. — litewave

That is a figure of speech. It might make no difference in terms of manipulating the concepts required to understand relativity theory, but it's the kind of difference that philosophy ought to consider.

Perhaps we infer universals from particular instances. — Banno

says John Stuart Mill, and the other empiricists, but I do realise that we're at the boundary of what you consider acceptable, so I won't press the point. -

Evolution, creationism, etc?The philosophical issue comes down to one word: purpose. Any ideas of purpose, and therefore meaning, were jettisoned by early modern science, associated with the dreaded scholasticism. The only admissable kinds of causes were what the scholastics would call material and effiecient causes. So, in the Aristotelian sense, nothing happens in evolutionary theory for any reason, other than to propogate. And all behaviours are subordinated to, and explained by, that requirement.

A bit more reading - Evolution and the Purposes of Life, Steve Talbott. -

On whether what exists is determinateSomething exists only if there is a suitable description of that thing. — Banno

Right. And aren't universals the determinates of predication? Insofar as the mind is capable of grasping universals, then it is able to specify what that thing is. 'No entity without identity'. That is the subject of the Kelly Ross essay on my profile page, Meaning and the Problem of Universals. -

On whether what exists is determinateHowever, i must point out that the world of shared meanings has a massive subjective component, and is not necessarily universal like mathematics. — Merkwurdichliebe

Of course. But I question the naturalistic assumption that there's a clear-cut division between 'in the mind' (subjective, internal) and 'in the world' (objective, external). What that sense is, in actuality, is one of the underlying dynamics of 'the human condition' - that sense of otherness or separateness from the world (recall Alan Watts' books). You do find, in classical philosophical literature, scattered references to the 'union of knower with known' - which harks back to the insight that transcends this 'illusion of othernesss'. And that, I say, is something lost to modern philosophy, due to its incompability with individualism.

You are not here saying that whatever we believe to exist has an associated description; that if we encounter a previously-unseen celestial object, there is a description of what kind of thing it is? — Banno

What I was trying to say is that I think there's a widespread assumption that phenomena comprise the whole of reality. So that, were we to discover a previously-unknown planet - there must be trillions of them - it's simply a question of discovering another instance of something that is already familiar, another phenomenally real object*.

Whereas what is indeterminate does not exist in that sense. It is not 'out there somewhere'. And note how easily that expression is taken to indicate 'everything that might exist'. The previously-discussed Smithsonian essay on the nature of maths says:

Some scholars feel very strongly that mathematical truths are “out there,” waiting to be discovered—a position known as Platonism.

You see the point? If it's real, it must be out there - i.e. 'existing in time and space'. Whereas, I'm of the view that intelligible objects (such as number) are real - same for everyone - but not existent - they're not out there somewhere. But if they're not 'out there' then where are they? Aha, comes the conclusion, 'in the mind'. But they're the same for all minds, do they're not subjective, either. In fact, neither subjective nor objective - but those two categories exhaust our instinctive ontology of what the world must be like.

So, in pre-modern and early modern philosophy, 'phenomenon' was one of a pair, the other term being 'noumenon' (not necessarily in the strictly Kantian sense) meaning appearance and reality. So my sense is that due to the overwhelming influence of empiricism and (broadly speaking) positivism, that we now have a conviction that only phenomena are real - that the totality of the universe comprise phenomena, 'out there somewhere', and apart from that, there's only the internal, private, subjective domain. So, back to that Smithsonian essay:

Scientists tend to be empiricists; they imagine the universe to be made up of things we can touch and taste and so on; things we can learn about through observation and experiment. The idea of something existing “outside of space and time” makes empiricists nervous: It sounds embarrassingly like the way religious believers talk about God, and God was banished from respectable scientific discourse a long time ago.

This is an undercurrent to a lot of the debates on this forum.

----

* There are of course kinds of objects, like black holes and various sub-atomic particles, which we have never empirically validated but which are predicted to exist by mathematical physics. But whatever they may be, they're still 'out there somewhere', or supposed to be. -

On whether what exists is determinateRather peculiar to refer to math as an intelligible object since the intelligible is subjective. — Merkwurdichliebe

Not so. Your seven is exactly identical to mine. Otherwise nothing would ever work. They're not subjective, but they're only discernable to the mind. The base confusion of the modern world is that 'in the mind' means 'subjective'. We live in a world of shared meanings.

But are you saying something like that there are no individuals, only descriptions? That an individual is some sort of shorthand for a definite description? — Banno

No, I'm interested in the reality of intelligible objects. I was recently reading about the idea that the form of a thing determines its nature:

[Kant's] starting point...is the dualism between sensibility and intellectuality, which is a species of the relation between the determinable and its determination.

Pollok, Konstantin. Kant's Theory of Normativity: Exploring the Space of Reason (p. 118). Cambridge University Press. Kindle Edition.

Now notice the similarity to this passage:

if the proper knowledge of the senses is of accidents, through forms that are individualized, the proper knowledge of intellect is of essences, through forms that are universalized. Intellectual knowledge is analogous to sense knowledge inasmuch as it demands the reception of the form of the thing which is known. But it differs from sense knowledge so far forth as it consists in the apprehension of things, not in their individuality, but in their universality.

Thomistic Psychology: A Philosophical Analysis of the Nature of Man, by Robert E. Brennan.

I'm trying to trace this theme back through the history of ideas.

Ok, so in a limited (physicalist) sense you could say that extraspatiotemporal objects are not determinate, but in a general (mathematical) sense they are just as well-defined and hence determinate as spatiotemporal mathematical objects. — litewave

I guess you could say that. -

On whether what exists is determinatethere are interminable arguments in philosophy of mathematics as to whether maths is invented or discovered, whether it's in the mind of humans or is something real in the world." — Merkwurdichliebe

And it's a subject of great interest to me, and one of the motivations for this thread.

Well, they are not nothing and so they are something. — litewave

You're glossing over a fundamental philosophical distinction in saying that. As I noted above, one of the points of interest in the Kastner paper on quantum physics is this:

three scientists argue that including “potential” things on the list of “real” things can avoid the counterintuitive conundrums that quantum physics poses. ... At its root, the new idea holds that the common conception of “reality” is too limited. By expanding the definition of reality, the quantum’s mysteries disappear. In particular, “real” should not be restricted to “actual” objects or events in spacetime. Reality ought also be assigned to certain possibilities, or “potential” realities, that have not yet become “actual.” These potential realities do not exist in spacetime, but nevertheless are “ontological” — that is, real components of existence.

“This new ontological picture requires that we expand our concept of ‘what is real’ to include an extraspatiotemporal domain of quantum possibility,”...

Considering potential things to be real is not exactly a new idea, as it was a central aspect of the philosophy of Aristotle, 24 centuries ago. An acorn has the potential to become a tree; a tree has the potential to become a wooden table. Even applying this idea to quantum physics isn’t new. Werner Heisenberg, the quantum pioneer famous for his uncertainty principle, considered his quantum math to describe potential outcomes of measurements of which one would become the actual result. The quantum concept of a “probability wave,” describing the likelihood of different possible outcomes of a measurement, was a quantitative version of Aristotle’s potential, Heisenberg wrote in his well-known 1958 book Physics and Philosophy “It introduced something standing in the middle between the idea of an event and the actual event, a strange kind of physical reality just in the middle between possibility and reality.”

Note 'extraspatiotermporal' which in plain language means 'not in time and space'. So these kinds of 'objects' are not existent in the sense that phenomena are existent, as phenomena exist in time and space. The act of measurement literally precipitates them as phenomena (which is the very implication that the many worlds intepretation seeks to avoid, by saying that this never happens.) Bohr said 'no elementary phenomena is a phenomena until it is a registered (observed) phemomena'. So here you're actually seeing a demonstration of the borderline between phenomenal and noumenal.

Prima facie it seems odd for someone with an idealist bent to hark back to Bertrand Russell. — Banno

I'm interested in the meaning of universals and other such intelligible objects. -

On whether what exists is determinateaccording to classical metaphysics, the concept 'apple' subsists while the particular apple exists.

I am using the term object simply as "something". — litewave

But that's what I'm questioning. Such 'objects' as the wave equation, or many other logical or mathematical laws and principles, do not exist as things, but only as intelligible objects - they are only perceptible to a rational mind, not to empirical observation although they may have empirical implications. -

On whether what exists is determinatea precisely defined mathematical object...And spaces themselves are mathematical objects. — litewave

Using the term 'object' metaphorically, don't you think? They are what would be called in philosophy a 'noetic object', meaning 'only perceptible by the intellect.' -

Is there an external material world ?"The mind" is not an empirical object, to be sure, but it is also not determinably anything more than a concept. — Janus

How could the mind be a concept? The mind is the faculty by which concepts are grasped. Of course, completely defining something as basic as 'concept' is a tricky business but going with the dictionary entry '1. something conceived in the mind : thought, notion. 2 : an abstract or generic idea generalized from particular instances the basic concepts of psychology the concept of gravity.' So, the mind is the faculty which can grasp concepts, but that doesn't make the mind itself a concept, although philosophers will have various concepts of mind. -

On whether what exists is determinateThere is a modal realist interpretation of quantum mechanics where all quantum possibilities are regarded as real/determinate - the many worlds interpretation, which currently seems to be the favorite interpretation with physicists. — litewave

While I'm not a physicist, I feel the MWI is posited purely as a means to avoid the anti-realist implications of the 'Copenhagen interpretation'. The problem it sets out to solve is the so-called 'wave function collapse', by declaring that it is not necessary, but at the cost of introducing infinite branching universes. To me it seems blatantly obvious that in this case, the solution is infinitely worse than the problem. (See Sean Carroll's 'most embarrasing graph in modern physics'.)

What would be the ontological difference between a potentially real object and an actually real object? — litewave

Actual existence, I would think. If it's only potentially real, then it doesn't exist. In is in that sense that electrons and the like can be said to only have a tendency to exist. The wave function is a distribution of possibilities, but it's not as if the object is in a definite but undisclosed location, it has no definite location until it is measured. (Different type of answer to joshs, mine is drawn mainly from Nature Loves to Hide, Shimon Malin.)

So one of the key things about the 'potentia' view is the idea that there can be degrees of reality. That, I think, is something that has been lost. -

Is there an external material world ?I asked if it actually did. there's no rational argument can be brought to bear on that question. It's answered with examples. — Isaac

You understand why that is implicitly empiricist? In any case, the examples of philosophy are, of course, the philosophers, although that looses cogency in modern culture, where the subject has become an academic speciality (except for the exemplary few actual popular philosophers, like Jules Evans, Alain du Bouton, Eckhart Tolle.) -

On whether what exists is determinateWhat I mean by cosmic philosophy, is a philosophy in which life is integral to the Cosmos, not an accidental byproduct of a meaningless process. (Although it's arguable that the term 'cosmos' insofar as it refers to 'a unified whole' is no longer meaningful.)

-

Climate change denialhttps://www.abc.net.au/news/2022-07-20/united-kingdom-record-temperatures-fires-burn-london/101252668

The birthplace of the Industrial Revolution is now reaping the whirlwind. -

On whether what exists is determinateI'm interested in a lot of things. — Tom Storm

I guess what I’m asking is, do you think the difference between a philosophy that makes a place for the significance of life, and one that doesn’t, is significant? I mean, as far as philosophies go, there can't be a much greater degree of difference.

A meta narrative is a claim to universal truth. — Joshs

I'm interested in the possibility of a cosmic philosophy. Maybe that's what cosmology is supposed to be. In any case, our culture doesn't have one. All we have is the remnants of passed ones. -

Evolution, creationism, etc?Evolutionary biology is a scientific discipline.

Neo-darwinian materialism (Dawkins, Dennett etc) is a philosophical ideology which claims support from evolutionary biology - however that is contested.

Creationism is linked to American Protestant Fundamentalism and is a religious ideology.

Intelligent design is arguably an offshoot of creationism which claims to demonstrate the inadequacy of Darwinian theory with reference to arguments from irreducible complexity.

The debate between scientific materialism and religious fundamentalism is one of the frontlines of the so-called 'culture wars'.

There are also many divergent views from within science about the overall adequacy of darwinian principles, a recent one being Do we need a new theory of evolution? (Guardian). See also The Third Way. -

On whether what exists is determinatePast cultural history( sciences. philosophy , art) is made use of in a transformed way. — Joshs

Fair enough. I guess that is where hermeneutics is important. -

Is there an external material world ?In any case in that paper it is asseted that Kant rejects introspection, while saying that behavior can only be understood subsequent to "studying the mind". How would it be possible to study the mind other than via observing behavior, if introspection is ruled out? — Janus

That's a very interesting question. One of the papers that @Joshs linked to is about that - Killing the Straw Man: Dennett and Phenomenology. It distinguishes between the 'straw man' depiction of introspection as the mere 'reporting of what comes to mind', and the discipline involved in phenomenological analysis illustrated with reference to Husserl's Logical Investigations.

Skinner was one of the two guys I loved to hate as an undergrad. (The other being Ayer.) -

On whether what exists is determinateI find it hard to see what difference this makes to a life lived. — Tom Storm

Something about it must interest you, otherwise why would you keep asking questions about it? -

On whether what exists is determinateRead Lucretius' De rerum natura — 180 Proof

Did a term paper on it, as part of Keith Campbell's Philosophy of Matter course. -

Is there an external material world ?Behavourism eschews any consideration of the mind whatever, so it's not likely!

Wayfarer

Start FollowingSend a Message

- Other sites we like

- Social media

- Terms of Service

- Sign In

- Created with PlushForums

- © 2026 The Philosophy Forum