Comments

-

Why is the Hard Problem of Consciousness so hard?

that is the inside of their body, not the inside of their experience.I take a picture of with an x-ray that I can look at and see what is inside the person — T Clark -

Why is the Hard Problem of Consciousness so hard?Indeed. But there are philosophies that explore the limits and the transcendence of discursive analysis. After all philosophy is the attempt to understand the meaning of being.

The function of insight gives a transcendental content that, when reduced to an interpretive system, becomes subject ot the relativity of subject-object consciousness. Therefore, there can be no such thing as an infallible interpretation. Thus we must distinguish between insight and its formulation. — Franklin Merrell Wolff (quoted in Nature Loves to Hide, Shimon Malin) -

Why is the Hard Problem of Consciousness so hard?The expansion of space is a difficult issue to wrap one's head around. — Metaphysician Undercover

Yes. Perhaps one's head would need to expand correspondingly. -

Truths, ExistenceAristotle, as per a podcast I'm listening to, invented the notions of potential and actual to harmonize Parmenides (no change) and Hercalitus (all change). — Agent Smith

Bingo. Right on the money there, Smith. -

Why is the Hard Problem of Consciousness so hard?Well, I'm arguing that they're two different aspects of the same overall problem. What I'm saying is that David Chalmer's rather awkward expression of 'what-it-is-like-ness' is really just a way of referring to 'being'.

When Chalmers said 'Facing Up to the Hard Problem', what he's saying is that science can't describe 'being' (or 'what it is like to be' something) because it only deals with objects that can be understood in third-person terms. His paper is explicitly about what can't be described in those terms, namely, subjective experience. Whereas, as I said before, the eliminative materialists argue as follows:

In Consciousness Explained, I described a method, heterophenomenology, which was explicitly designed to be 'the neutral path leading from objective physical science and its insistence on the third-person point of view, to a method of phenomenological description that can (in principle) do justice to the most private and ineffable subjective experiences, while never abandoning the methodological principles of science. — Daniel Dennett, The Fantasy of First-Person Science

So, from Chalmers' perspective, there is something that the eliminativists are not seeing. And I'm saying, what it is that they are not seeing corresponds with 'the blind spot of science'. It's another aspect of the same basic issue.

(Incidentally, this also means that 'the hard problem' is not a problem at all outside that particular context. It's simply a kind of rhetorical device.) -

Why is the Hard Problem of Consciousness so hard?Yes, exactly. Do you agree with that? — frank

:100: It's what I've been trying to argue for all along. The problem is one of perspective. Naturalism starts from the presumption of the separation of subject and object. From a methodological point of view, that is perfectly sound - when you are indeed studying objects. But humans are not objects - they're subjects of experience. That is precisely the distinction which the 'eliminativists' seek to get rid of - hence the attempt to describe human subjects as 'robots' or as 'aggregatations of biomolecular structures', and not as beings per se. -

Why is the Hard Problem of Consciousness so hard?Alternately, we could say that to make progress, the realm of the physical will have to be rethought such that we recognize that the subjective was always baked into the very structure of physical science, but in such a thoroughgoing manner that it was never noticed. — Joshs

:clap:

Do you see any relationship with this and Heidegger's 'forgetfulness of being'?

What do you think about the "eye can't see itself" issue? Is it ultimately futile to look for a theory of consciousness? — frank

See The Blind Spot of Science:

Our account of the Blind Spot is based on the work of two major philosophers and mathematicians, Edmund Husserl and Alfred North Whitehead. Husserl, the German thinker who founded the philosophical movement of phenomenology, argued that lived experience is the source of science. It’s absurd, in principle, to think that science can step outside it. The ‘life-world’ of human experience is the ‘grounding soil’ of science, and the existential and spiritual crisis of modern scientific culture – what we are calling the Blind Spot – comes from forgetting its primacy.

Whitehead, who taught at Harvard University from the 1920s, argued that science relies on a faith in the order of nature that can’t be justified by logic. That faith rests directly on our immediate experience. Whitehead’s so-called process philosophy is based on a rejection of the ‘bifurcation of nature’, which divides immediate experience into the dichotomies of mind versus body, and perception versus reality. Instead, he argued that what we call ‘reality’ is made up of evolving processes that are equally physical and experiential. -

US MidtermsMeanwhile in Kentucky.....

Rep. Ralph Norman of South Carolina has said a non-negotiable for him is if McCarthy is “willing to shut the government down rather than raising the debt ceiling.”

If these kinds of people cause a US debt default, then it's brush up your survival skills and buy lots of tinned supplies well in advance, because the resulting economic disruption will make The Great Depression seem like a picnic. And they're willing to do it! Some of them at least believe they are doing God's work. -

Is "good", indefinable?Ah yes, that must've been it. I copied a lot of quotes from this forum over the years.

-

Is "good", indefinable?Of course. Carry on.

(But then, I did read somewhere that 'The sense of the world must lie outside the world. In the world everything is as it is and happens as it does happen. In it there is no value—and if there were, it would be of no value.' Can't remember where, it's a scrapbook entry.) -

Is "good", indefinable?There's an expression one will sometimes happen across in the discussions of texts of spiritual philosophy, 'the good that has no opposite'. That is as near as you can get to an 'absolute good', as it connotes an unalloyed good. It is differentiated from what is good in ordinary discourse, where good is defined in terms of its opposite - good as distinct from bad (expressed in the taoist aphorism 'long and short define each other'.) Whereas the 'good that has no opposite' is an appeal to a good that lies beyond the opposites.

An example comes to mind from Mahāyāna Buddhism and the 'eight worldly concerns' (annotated by me):

hope for pleasure (good) and fear of pain (bad),

hope for gain (good) and fear of loss (bad),

hope for praise (good) and fear of blame (bad),

hope for good reputation and fear of bad reputation.

a commentary on that:

The World Knower (i.e. Buddha) has said:

Gain and loss, pleasure and pain,

Pleasant words and unpleasant words, praise and blame—

These are the eight worldly concerns.

Do not allow these concerns occupy your mind;

Regard them with equanimity.

Letter to a Friend by Nāgārjuna

Insofar as the 'definition' of the good is concerned, this doesn't offer a definition as such, which after all is only a matter of words, so much as a prescription whereby such an unalloyed good is to be sought. -

US MidtermsThey keep describing the republican dissidents as 'ultra conservatives', when in actual fact, as mentioned above, they're radicals. They don't want to govern, the want to bring down the government.

-

Why is the Hard Problem of Consciousness so hard?I approach the "first-person nature of experience" from the perspective of the difference between "inner and outer". — Metaphysician Undercover

That's what Bernardo Kastrup says. I think it's right, although I hadn't considered it from the perspective you suggest regarding the expansion of space. :chin: -

What jazz, classical, or folk music are you listening to?just watching that about 2 minutes ago. Zimmer is just totally digging it, he doesn’t know what to do with his hands ‘cause they’re not on a keyboard.

I found Govan through one of Rick Beato’s shows:

The versatility is amazing although I tried a couple of Govan’s albums and found them a bit too metallic for my tastes. -

Why is the Hard Problem of Consciousness so hard?I even understand why it's hard to imagine that that experience could be explainable in terms of biology and neurology. It's just so immediate and intimate. I can feel that, but I just don't get why people think that is any different from how all the other phenomena whirling around us come to be. — T Clark

Not seeing the point of an argument is not a rebuttal, but flogging dead horses is also not productive. -

Why is the Hard Problem of Consciousness so hard?I just don't see what the big deal is. I think it's just one more case, perhaps the only one left, where people can scratch and claw to hold onto the idea that people are somehow exceptional. — T Clark

Even though you've quoted the salient passage, you're not demonstrating insight into what the issue purports to be. The argument is about the first-person nature of experience - 'what it is like' is an awkward way of describing simply the nature of 'being'. Chalmers is pointing out that 'experience' or 'state of being' must always elude third-person description, because it's third person.

Whereas Daniel Dennett, who is Chalmer's antagonist in such debates, says straight out:

In Consciousness Explained, I described a method, heterophenomenology, which was explicitly designed to be 'the neutral path leading from objective physical science and its insistence on the third-person point of view, to a method of phenomenological description that can (in principle) do justice to the most private and ineffable subjective experiences, while never abandoning the methodological principles of science. — Daniel Dennett, The Fantasy of First-Person Science

So, Dennett is claiming that science can arrive at a complete, objective understanding of the human from a scientific point of view. There are many philosophers who have claimed this is preposterous - (Galen Strawson has said that he ought to be sued under Trade Practices for false advertising.) Among other things, this leads to Dennett's insistence that humans really are no different to robots, and that what we perceive as intelligence is really the consequence of the 'mindless' activities of billions of cellular connections that generate the illusion of intelligence (never mind that even an illusion requires a subject capable of suffering illusion).

Dennett's book Consciousness Explained was parodied as 'Consciousness Explained Away' or 'Consciousness Ignored' by many of his peers - not by your proverbial man-in-the-street but other philosophers, one of whom said that Dennett's claims were so preposterous as to verge on the deranged.

Nagel's review of Dennett's last book says:

Dennett asks us to turn our backs on what is glaringly obvious—that in consciousness we are immediately aware of real subjective experiences of color, flavor, sound, touch, etc. that cannot be fully described in neural terms even though they have a neural cause (or perhaps have neural as well as experiential aspects). And he asks us to do this because the reality of such phenomena is incompatible with the scientific materialism that in his view sets the outer bounds of reality. He is, in Aristotle’s words, “maintaining a thesis at all costs.”

Dennett is situated squarely in the middle of 'the blind spot of science' - there is something fundamental to philosophy that he is incapable of comprehending. So while I don't agree with Galen Strawson's solution, I certainly agree with his assessment of Daniel Dennett.

Hope you're doing well! — frank

Well, thanks! (although one of the reasons I had stopped posting for six months was because of this debate, I am continually mystified as to why people can't see through Dennett.) -

Why is the Hard Problem of Consciousness so hard?Chalmers is one of the most influential philosophers of our time. Seems like you'd be more interested to discover what his views actually are. — frank

:100:

There's been very little discussion of the actual issue. -

Why is the Hard Problem of Consciousness so hard?I will say that there is no reason the mind would not be among entities amenable for study by science. — T Clark

Well, pack it and send it, and I'll check it out. -

Why is the Hard Problem of Consciousness so hard?That science has not explained. I see no reason to believe it can't. — T Clark

It's not complicated. Science (or at least a lot of it) begins with the presumption of objectivity, that it is studying something that really so, independently of your or my opinions. It assumes the separation of subject and object, and attempts to arrive at objective descriptions of measurable entities. And the mind is not among those entities. The hardline eliminative materialists will insist that the mind nevertheless can be described completely in third-person terms without omission. That is the target of David Chalmer's original formulation of 'the hard problem', for instance, when he says:

The really hard problem of consciousness is the problem of experience. When we think and perceive, there is a whir of information-processing, but there is also a subjective aspect. As Nagel (1974) has put it, there is something it is like to be a conscious organism. This subjective aspect is experience. When we see, for example, we experience visual sensations: the felt quality of redness, the experience of dark and light, the quality of depth in a visual field. Other experiences go along with perception in different modalities: the sound of a clarinet, the smell of mothballs. Then there are bodily sensations, from pains to orgasms; mental images that are conjured up internally; the felt quality of emotion, and the experience of a stream of conscious thought. What unites all of these states is that there is something it is like to be in them. All of them are states of experience. — David Chalmers, Facing Up to the Hard Problem

My paraphrase of this is simply that experience is first-person. It cannot be fully described in third-person terms, as there must always be a subject to whom the experience occurs. What I think Chalmers is awkwardly trying to describe is actually just being, as in human being. And what I think the 'eliminativists' exemplify is what is criticized by philosophers as 'the forgetfulness of being'.

Husserl, as @Constance points out, anticipated this in his criticism of naturalism. -

The possibility of fields other than electromagneticIf you liked that, you'd love this.

-

The possibility of fields other than electromagneticBut ontologically, if 'two' fields are totally co-extensive, there's a sense in which they are one thing, no? — bert1

The point I was trying to make in the OP is that while magnetic field effects can be easily demonstrated by observing the behaviour of iron filings the existence of such things as 'morphogenetic fields' is much more difficult to establish.

The former can be demonstrated in a primary-school classroom with a magnet, some iron filings, and a sheet of paper, whereas the latter relies on sophisticated inferences from the observation of biological reproduction.

And as electromagnetic fields were described by Maxwell's equations, their effects can be observed to conform with predictions, which are nowadays fundamental in the operations of almost every electrical device.

Whereas even if there are field effects in biological systems, they might be much harder to observe because of the complexity of organisms and the range of possible explanations. That's where Sheldrake is at least relevant - at least he claims to have demonstrated morphic resonance, even if his many critics reject his findings. Again, morphogenic (or morphogenetic) field theory differs from Sheldrake's - whilst not being universally accepted it's also not regarded as fringe as I understand it.

There was a guy on one of the old forums, Alan McDougall, who always used to say that everything was waves and vibrations. I said we could test it - 'I'll wave, and you vibrate! :-) -

The possibility of fields other than electromagneticthanks, interesting article. I'm a fan of that writer, she produces some excellent material. (Notice there's a headline 'Good Vibrations' :-) )

-

The possibility of fields other than electromagneticThere's an essay on Sheldrake's website about reaction to his books, called 'The Sense of being Glared At' :-)

-

Truths, ExistenceQuestion: 'What is 'modal realism' in philosophy?'

ChatGPT: 'Modal realism is a philosophical theory that holds that possible worlds exist and are as real as the actual world. The theory was first proposed by the philosopher David Lewis, who argued that possible worlds should be understood as concrete, spatiotemporal entities rather than as abstract concepts or mere possibilities.

According to modal realism, possible worlds are like alternative versions of reality that could have been actualized but were not. These possible worlds may differ from the actual world in terms of their history, their physical laws, and the events that take place within them. Modal realism suggests that it is possible to talk about and make sense of these alternative realities as if they were real, even though they are not the actual world we happen to inhabit.

One of the main motivations for modal realism is to provide a more satisfactory explanation for modal concepts such as possibility and necessity. Modal realism allows us to understand these concepts in terms of the existence of possible worlds, rather than in terms of logical or epistemic notions that are more difficult to explain.

However, modal realism is a highly controversial theory and has been the subject of much criticism from philosophers. Some have argued that it is too speculative or that it lacks sufficient evidence to be taken seriously. Others have pointed out that it is difficult to see how modal realism could be reconciled with our common-sense understanding of the world.'

I've bolded what I consider the salient passage. What modal realism provides is that ideas such as possibility and necessity are 'concretized' by allowing that they have real existence in some possible world. It solves the problem of the way in which possibility and necessity can be conceived to be real.

This 'solution' is similar in many respects to the motivation behind the many-worlds interpretation of quantum physics. This too seeks to dissolve the apparent conundrum of the wave-function collapse by saying it doesn't really happen.

Again, I suggest that both these problems (which may be versions of the same problem) can be solved by recognising degrees of reality - that is, things can be more or less real. And I suggest the underlying philosophical problem is that modern philosophy generally has nothing which corresponds with the idea of 'degrees of reality'. The mainstream consensus is that things either exist, or they don't exist. There is no provision for different kinds or degrees of reality (which is what I would have thought 'modal metaphysics' really should be about.)

Werner Heisenberg explored these ideas in his writings on physics and philosophy. This article says that

At its root, the new idea holds that the common conception of “reality” is too limited. By expanding the definition of reality, the quantum’s mysteries disappear. In particular, “real” should not be restricted to “actual” objects or events in spacetime. Reality ought also be assigned to certain possibilities, or “potential” realities, that have not yet become “actual.” These potential realities do not exist in spacetime, but nevertheless are “ontological” — that is, real components of existence.

“This new ontological picture requires that we expand our concept of ‘what is real’ to include an extraspatiotemporal domain of quantum possibility,” write Ruth Kastner, Stuart Kauffman and Michael Epperson.

Considering potential things to be real is not exactly a new idea, as it was a central aspect of the philosophy of Aristotle, 24 centuries ago. An acorn has the potential to become a tree; a tree has the potential to become a wooden table. Even applying this idea to quantum physics isn’t new. Werner Heisenberg, the quantum pioneer famous for his uncertainty principle, considered his quantum math to describe potential outcomes of measurements of which one would become the actual result. The quantum concept of a “probability wave,” describing the likelihood of different possible outcomes of a measurement, was a quantitative version of Aristotle’s potential, Heisenberg wrote in his well-known 1958 book Physics and Philosophy. “It introduced something standing in the middle between the idea of an event and the actual event, a strange kind of physical reality just in the middle between possibility and reality.”

The problem for modern philosophy, however, is that the 'realm of possibility' can only be understood as being 'in the mind' - that is, subjective, and therefore not 'objectively real'. That is the central conundrum in my view. -

The possibility of fields other than electromagneticThere are as many answers as there have been scientific discoveries, but one thing is common to all of them: merely positing "subtle forces that hadn’t yet been discovered" won't cut it, even if you make up a sciency-sounding name for these subtle forces, such as "morphic fields." — SophistiCat

According to the abstract for the article I mentioned in the OP, morphogenetic fields have a long history, and address specific problems in biology (although I haven’t been able to access the paper in full.)

There’s a well–known interview with an editor of Nature who had remarked in his review that Rupert Sheldrake’s first book which introduced his morphic fields was ‘a book for burning’. When asked later as to why he made this remark, he said that ‘Sheldrake is putting forward magic instead of science, and that can be condemned in exactly the language that the Pope used to condemn Galileo, and for the same reason. It is heresy.’ And why it is ‘heresy’ is because there is no discernible medium in which Sheldrake’s ‘habits of nature’ can be formed or transmitted. In his terms, there is no mechanism for such formations, such as that provided by genetic transmission. However, interestingly, one rather more mainstream figure whose ideas may be convergent with Sheldrake’s in some respects was C.S. Pierce, who also posited that ‘nature forms habits’. But the point is, these proposals undermine the predominantly mechanistic explanations that underlie the scientific worldview, and that’s why they’re deemed heretical. -

The possibility of fields other than electromagneticthanks Jack, appreciated. I've always liked Sheldrake but I'm mindful of his critics, although their stridency is revealing. I suppose the specifically philosophical point is that, until electromagnetic field effects were discovered, nobody really had any idea of 'fields' as such, but I wonder if there might be other kinds of fields and if so how they would manifest and how they would be detected.

-

The possibility of fields other than electromagnetica quantum field is the one you're talking about when you reference "atomic particles are conceived of as 'excitations of fields'.." — T Clark

Right, that's what I was thinking of.

There are no tides in Evanston, Illinois. — T Clark

That's the point - that's what made it an anomaly. Frank Brown took oysters from the Eastern seaboard and sealed them in a tank in Evanston with no exposure to sunlight or the elements. Over the next month or so, their opening/closing timelines shifted to match what the tide would be in that location, had there been tides.

I am definitely a skeptic about any ideas of exotic or hidden fields that have important effects which have not been identified. — T Clark

Right. That is also what befell Frank Brown.

Brown concluded that the organisms were sensitive to external geophysical factors, perhaps minute fluctuations in gravity, or even subtle forces that hadn’t yet been discovered. ...Such ideas were viewed as threatening by his peers. Several of them had fought to have their own work on daily cycles taken seriously by other scientists. Their professional respectability hinged on using rigorous, reproducible methods, and basing their theories on impeccable physical principles of cause and effect; Brown’s claims of mysterious forces were dangerous nonsense that jeopardized the field. His measurements weren’t accurate enough, they insisted, or he was seeing patterns in his highly complex data that simply weren’t there. Yet Brown was charismatic and articulate, and he was swaying public opinion.

So that's the point I'm exploring. Why is it that some types of explanations were regarded as scientifically appropriate or sound or acceptable, and others were not? -

What jazz, classical, or folk music are you listening to?I’ll definitely give it a listen. Also Guthrie Govan, also mainly on YouTube.

-

What jazz, classical, or folk music are you listening to?Polyphia featuring Steve Vai, — busycuttingcrap

(Couldn't find anything about the second name he mentioned. Al Di Meola gives him a big rap too and featured him in a duo concert.) -

Truths, ExistenceSo I asked the question:

Wayfarer: What is it with Hans Meinong and 'the golden mountain'?

ChatGPT: ... As for "the golden mountain," it is a term that Meinong used to refer to an imaginary object that does not actually exist. He used this example to illustrate the idea that there can be objects of thought or reference that do not have any physical existence, but that can still be meaningful and have properties. The concept of the golden mountain is often used in discussions of Meinong's theory of non-existent objects, which holds that there can be objects of thought or reference that do not exist in any sense, but that can still be the subject of true or false statements."

But as I said above, things you can just think up with no referent, are not in the same class as (for instance) the real numbers, which likewise only exist as 'intelligible objects' but are the same for all who can count. -

Truths, ExistenceNo, didn't know that. I'm really enjoying playing with it. And also with Lensa, which turned me into an astronaut.

Oh, and if that is all Meinong said, then I can't see the controversy, but for some reason, the term 'golden mountain' always comes to mind when I hear the name. -

Truths, ExistenceNumbers are not tangible, tangible meaning 'able to be touched'. What makes them the subject of direct experience is that anyone can count, and practically everyone learns arithmetic.

-

Truths, Existenceeverything exists (in some possible world). — Agent Smith

https://www.theatlantic.com/science/archive/2016/08/the-multiverse-as-imagination-killer/497417/

Well, it's not quite the multiverse, but it's as good as. I never understood the point of Meinong.

Bugs Bunny or Super Mario exist as fictional characters in cartoons and computer games. The names have referents and the figures have characteristics - Bugs is a rabbit, not a camel or a penguin. They exist as works of fiction but that is still a kind of existence. But if I dream up some fictional cartoon character purely of my own imagining, that nobody else knows about, I would not grant it any kind of existence whatever.

I tossed the question to ChatGPT:

Wayfarer: 'What is the main point of the philosophy of Hans Meinong?'

ChatGPT: ' Hans Meinong was an Austrian philosopher known for his work in metaphysics and the philosophy of psychology and language. One of the main points of his philosophy was his theory of objects, which was a response to the problem of how we can talk about and think about objects that do not exist in the same way that physical objects do. Meinong argued that there are many kinds of objects that we can talk about, including abstract objects like numbers and moral values, and that these objects have a kind of existence that is different from the existence of physical objects. He also argued that we can have meaningful thoughts and statements about these kinds of objects, even though they do not have a physical presence.'

Now, that I agree with, but I would limit the kinds of 'objects' to such as numbers, geometrical axioms, principles, and the like. I have long argued that (at least some of these) are real but not existent in the way that tables and chairs are. It's not 'anything goes' - there are no actual unicorns or square circles or married bachelors, and they are therefore not the subject of any meaningful statement. But the natural numbers (for instance) really do have a different kind of reality or existence to chairs and tables - which is a problem for modern philosophy, as it presumes that there cannot be different kinds or modes of existence or reality: that something either exists, or it doesn't. Whereas in Platonist epistemology, there are different levels of knowing, corresponding to different classes of objects (see the Analogy of the Divided Line). -

What jazz, classical, or folk music are you listening to?To anyone who likes authentic jazz-rock fusion - hey, I know you're an elite group - check this out. Drift Lab, an Italian quartet, no released albums as such, denizens of YouTube. All master musicians but particular call out to Matteo Mancuso who to my mind is the best electric guitarist in the world today (and I know guitarists. Plays electric guitar with flamenco technique. Absolute master. If you're into guitarists, check him out.)

-

Is there an external material world ?The key realisation arising from quantum physics was the fact that the observer has a direct role in determining the outcome of the observation of purportedly the fundamental building blocks of the world. That is what disturbed Einstein's realist assumptions, it is why he asked the question 'Doesn't the moon continue to exist when nobody's looking at it?'

What is at issue is the naturalist assumption that the Universe just is as it is, and will be that way, without any observer present. That is what I call 'realism', and it has been called into question by these discoveries. It is documented in many books, such as Manjit Kumar: Quantum: Einstein, Bohr, and The Great Debate about the Nature of Reality. Ask yourself: why would this book have that sub-title if there were no such debate? Do you think he's just making stuff up? (Read it if you want to find out.) Another useful book I've read is David Lindley's Uncertainty: Einstein, Heisenberg, Bohr, and the Struggle for the Soul of Science :

Werner Heisenberg's 'uncertainty principle' challenged centuries of scientific understanding, placed him in direct opposition to Albert Einstein, and put Niels Bohr in the middle of one of the most heated debates in scientific history. Heisenberg's theorem stated that there were physical limits to what we could know about sub-atomic particles; this 'uncertainty' would have shocking implications.

So, what are these 'shocking implications'? Why did Neils Bohr feel compelled to ask, after delivering a lecture to the Vienna Circle and recieving their sanguine applause, 'if you're not shocked by quantum physics, then you can't possibly have understood it!' (this anecdote is recounted in Heisenberg's book, Physics and Beyond.)

I could produce a dozen more passages, but I will only mention only a couple more from the interview with Chris Fuchs whose interpretation is called Quantum Bayesianism, normally contracted to QBism. I've bolded the passage that I think articulates the important point.

Q: In one of your papers, you mention that Erwin Schrödinger wrote about the Greek influence on our concept of reality, and that it’s a historical contingency that we speak about reality without including the subject — the person doing the speaking. Are you trying to break the spell of Greek thinking?

A: Schrödinger thought that the Greeks had a kind of hold over us — they saw that the only way to make progress in thinking about the world was to talk about it without the “knowing subject” in it. QBism goes against that strain by saying that quantum mechanics is not about how the world is without us; instead it’s precisely about us in the world. The subject matter of the theory is not the world or us but us-within-the-world, the interface between the two.

Some other snippets:

Q: Does that mean that, as Arthur Eddington put it, the stuff of the world is mind stuff?

A: QBism would say, it’s not that the world is built up from stuff on “the outside” as the Greeks would have had it. Nor is it built up from stuff on “the inside” as the idealists, like George Berkeley and Eddington, would have it. Rather, the stuff of the world is in the character of what each of us encounters every living moment — stuff that is neither inside nor outside, but prior to the very notion of a cut between the two at all.

Those familiar with non-dualism will recognise that.

My fellow QBists and I instead think that what Bell’s theorem really indicates is that the outcomes of measurements are experiences, not revelations of something that’s already there. Of course others think that we gave up on science as a discipline, because we talk about subjective degrees of belief. But we think it solves all of the foundational conundrums.

Charles Pinter also mentions QBism in this comment:

According to quantum Bayesianism, what traditional physicists got wrong was the naïve belief that there is a fixed, “true” external reality that we perceive “correctly”. Quantum Bayesianism claims that instead, the scientific observer sees the readings on his instrument and understands that they bring him new information pertaining to his mental model of reality. He has abandoned the belief that he is seeing the real world “as it truly is”.

Pinter, Charles. Mind and the Cosmic Order (p. 167). Springer International Publishing. Kindle Edition.

My take: mind is nothing objectively existent, there really is no such thing. But we never know anything apart from it. -

Is there an external material world ?the metaphysical implications of quantum mechanics, if any, are far from settled. — Banno

Sure. But if it didn’t challenge scientific realism, then there wouldn’t even be a metaphysical question. -

Is there an external material world ?Excellent interview with the founder of QBism here.

Philip Ball on why the many worlds interpretation sucks.

Bernard D'Espagnat says what we call reality is just a state of mind.

The only definite fact in all of this is that quantum physics undermines realism. -

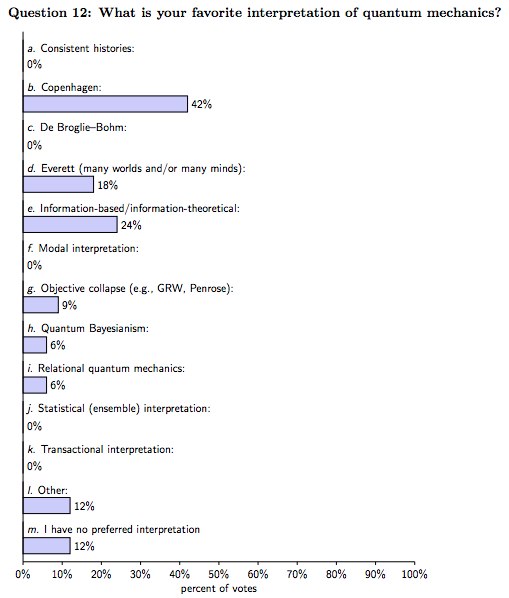

Is there an external material world ?Poll carried out by Maximilian Schlosshauer, Johannes Kofler, and Anton Zeilinger at a quantum foundations meeting. The pollsters asked a variety of questions which were patiently answered by the 33 participants. Here are the results:

From here.

Wayfarer

Start FollowingSend a Message

- Other sites we like

- Social media

- Terms of Service

- Sign In

- Created with PlushForums

- © 2026 The Philosophy Forum