-

Bob Ross

2.6kModern society is decaying; and this decay is a direct result of moral anti-realism. It is hard to say why moral anti-realism has caught wind like wild fire, but I would hypothesize it is substantially influenced by Nietzschien thought.

Bob Ross

2.6kModern society is decaying; and this decay is a direct result of moral anti-realism. It is hard to say why moral anti-realism has caught wind like wild fire, but I would hypothesize it is substantially influenced by Nietzschien thought.

With this moral anti-realism, society slowly loses it’s ability to function rationally (since it has cut out The Good from its inquiry) and begins to cause people to damage themselves in the name of “you-do-you!”. As Nietzsche rightly pointed out: “All of us are no longer material for a society” – (The Gay Science, Book V, p. 304).

The form of moral anti-realism taking prominence, is this “Nietzschien kind”. Not only is it bad for a human to think they can acquire happiness through fulfilling their desires but this sort of thought leads to the crumbling of society into arbitrary, narcissistic power-struggles. None of which is good for people.

Interestingly enough, aristotelian ethics provides anecdotes to many of the issues emerging as an effect of this Nietzschien thought; and, therefore, I suggest society by-at-large goes back to aristotle’s ideas (for the most part) to live a better life. I would like to take this post to elaborate on some of the key aspects of his ethics, of which can greatly help the populace better live their lives (than this common, Nietzschien alternative).

Teleology

“Every art and every inquiry, and similarly every action as well as choice, is held to aim at some good” – (Nichomachean Ethics, Book I, Ch. 1, p. 1)

The first key element of aristotelian ethics, is looking upon everything in life through the lens of telos and seeing the good as things living up thereto. A good eye is an eye that can see well; a good clock is one that can tell the time well; etc.

People get way too entrenched in their radical individualism these days, and this causes them to damage themselves irreversibly in the name of fulfilling their desires (all the while thinking they are contributing to their own happiness). If people were constantly, instead, thinking about how they could fulfill their nature (as a human being) then they would be able to better navigate their lives to secure a deep and persistent sense of happiness.

Now, there is a common objection to this sort of thinking which I address later on. For now, I will comment that I think that everything should be viewed through the lens of telos as it relates to well-being (i.e., eudamonia) and not just telos simpliciter; but Aristotle, on the contrary, accepts a stronger version of teleology than I would (whereof everything has a purpose towards what is ultimately good, as per the dictations of the Nous).

Eudaimonia

“Happiness [eudaimonia] appears to be something complete and self-sufficient, it being an end of our actions” – (Nichomachean Ethics, Book I, Ch. 7, p. 12)

The chief good for a human being is to be a eudaimon (viz., to embody the chief good [for human beings] of eudamonia [i.e., of a deep and persistent sense of happiness, flourishing, and well-being]); and this is the most persistently satisfying and deeply rewarding pursuit a person can endeavor on. Everything else is, if it does not relate somehow thereto, a mere distraction.

People seem to have a sense that happiness is key to a good life; but seem to be utterly confused on how to achieve it nowadays: they seem to think it has to do with being radically individualistic and/or hedonistic—it doesn’t.

Now, there is an objection worth noting that, prima facie, the pursuit of one’s own happiness, and that being the chief good, seems pretty narcissistic. I will address that later hereon.

Virtue

“So it must be stated that every virtue both brings that of which it is the virtue into a good condition and causes the work belonging to that thing to be done well. For example, the virtue of the eye makes both the eye and its work excellent, for by means of the virtue of the eye, we see well...If indeed this is so in all cases, then the virtue of a human being too would be that characteristic as a result of which a human being becomes good and as a result of which he causes his own work to be done well.” – (Nichomachean Ethics, Book II, Ch. 6, p. 33)

“The happy [eudemian] life also seems to be accord with virtue, and this is the life that seems to be accompanied by seriousness but not to consist in play...If happiness [eudaimonia] is an activity in accord with virtue, it is reasonable that it would accord with the most excellent virtue, and this would be the virtue belonging to what is best” – (Nichomachean Ethics, Book X, Ch. 6-7, p. 223)

A key aspect of living well for a human being (and, arguably, any member of a rational kind) is living a (morally and intellectually) virtuous life; but it is important to note that, for Aristotle, “virtue” is not a morally-loaded term. For Aristotle, “virtue” is a sort of excellence which is relative to the subject, craft, etc. in question; whereas “moral virtue” is the subtype of virtue which is about moral excellence—i.e., doing well at being moral. It can be seen more clearly now that a person who wants to fulfill their nature must excel in every regard to that nature (i.e., must be virtuous); and a part of this is being moral, as morality pertains fundamentally to how to act best in accordance with what is good.

Being vs. Doing

“moral virtue is the result of habit...[and] none of the moral virtues are present in us by nature, since nothing that exists by nature is habituated to be other than it is” – (Nichomachean Ethics, Book II, Ch. 1, p. 26)

An important distinction in Aristotle’s ethics, which is largely ignored in modern times, is the difference between doing something and being something: the former is a mere action related to that something, whereas the latter is an embodiment of that something (viz., is a way of living which best exemplifies that something). I am not thereby a healthy person by doing something that is healthy; and, likewise, I am not thereby a good person by doing something that is good. Being good, healthy, etc. is about cultivating habits of character which best align with, that best embody, what is good, healthy, etc.

People very often think they are a good person for merely forcing themselves to do something good (when they could have chosen not to); when, in reality, they are not a good person if they have to fight their own impulses to do the right thing.

Principle of the Mean

“Virue, therefore, is a characteristic marked by choice, residing in the mean relative to us, a characteristic defined by reason and as the prudent person would define it. Virtue is also a mean with respect to two vices, the one vice related to excess, the other to deficiency” – (Nichomachean Ethics, Book II, Ch.6, p. 35)

Moral virtue, which pertains to right and wrong behavior, is, according to Aristotle, all about cultivating the mean habit out of two extremes—for this will best help a person live a well principled life via reason. For example, the mean between niceness and meanness is kindness; and the mean between cowardice and rashness is courageousness. These are (moral) virtues exactly because they are, with respect to their topics of behavior, the most well-regulated (with reason) habits of character; whereas the (moral) vices are vicious exactly because they are the passions overtaking reason and causing the person to live a poorly-regulated life.

People tend, nowadays, to think that happiness is about chasing pleasures and avoiding pains; but this couldn’t be further from the truth: living a well-regulated life—i.e., a morally virtuous life—is going to give one a deep and persistent sense of happiness.

Objection 1: What Telos?

A common objection to Aristotelian ethics is that there are no good reasons to believe in telos. Afterall, nature is an ever-going process of evolution—so where’s the telos?

Firstly, Aristotle believed in “God” (i.e., the Nous) and so, for him, there is telos in everything. However, I think with the advancements in science (such as evolution) we do need to give a more adequate response than Aristotle has in his works.

There are two types of telos: strong and weak. The former is purpose endowed by an agent (whether that be God or a human or what not), whereas the latter is purpose endowed by an non-agent. My house has strong telos, because it was developed and designed by human beings for the purpose of shelter and housing. Whereas my eye was not, at least for my fellow naturalists, not designed by any agent but, rather, underwent (and is undergoing) a process of evolution; however, this does not negate the fact that my eye is designed to see (and in a particular kind of way) and, consequently, it has a weak form of telos.

At worst, the answer to this objection is to note that the kinds of telos which the objector is finding missing is really weak teleology or not relevant to living a good life (because it does not relate to well-being).

At best, one could accept a form of theism that gets around this objection.

Objection 2: Fails the Is-Ought Gap Test

Aristotle never addresses the is-ought gap because, quite frankly, it wasn’t considered an issue back then; but, for us in the modern era, we do need to at least address it.

The is-ought gap objection would go something like this: “it seems as though that one should fulfill their nature does not follow immediately from the fact that one needs to fulfill their nature to achieve happiness; and so it seems as though Aristotle is just appealing to ‘obviousness’ to justify what is good being a thing fulfilling its nature”.

Because I happen to think the is-ought gap is a force to be reckoned with, I actually think Aristotle’s original positions falls prey to the is-ought gap and, thusly, this objection prima facie succeeds. However, I think Aristotelian ethics can be salvaged quite easily: what is good is what is (positively) intrinsically valuable, and what is the most (positively) intrinsically valuable is well-being in the deepest, richest, and most persistent sense. If this is true, then the fact that one should fulfill their nature follows validly from them needing to fulfill their nature to achieve eudamonia.

Objection 3: Narcissism

The third most common objection is that Aristotelian ethics instructs people to care about other people only insofar as it relates to them achieving their own happiness; which is morally counter-intuitive since it is incredibly narcissistic.

Aristotle’s response sort of bites the bullet (so to speak), by accepting that one should only care about people as it relates to their own happiness but that rational creatures cannot achieve happiness (in a supreme sense) without caring about other people.

I would say, contrary to Aristotle, that the moral person cares about what is good indiscriminately and, consequently, should care about the well-being of all living beings (even though they may have to prioritize some over others pragmatically but yet still in an unbiased fashion). There is no need, under my view, to paradoxically collapse narcissism into altruism in my interpretation of Aristotelian thought.

Thoughts? -

Leontiskos

5.6kGood post, I agree in large part. :up:

Leontiskos

5.6kGood post, I agree in large part. :up:

"Virtue is also a mean with respect to two vices, the one vice related to excess, the other to deficiency” – (Nichomachean Ethics, Book II, Ch.6, p. 35) — Bob Ross

People tend, nowadays, to think that happiness is about chasing pleasures and avoiding pains; but this couldn’t be further from the truth: living a well-regulated life—i.e., a morally virtuous life—is going to give one a deep and persistent sense of happiness. — Bob Ross

I think Aristotle's mean is very important. People think happiness is about chasing pleasures and avoiding pains, but they also fail to observe the mean in explicitly moral thinking. For example, I was recently having a discussion with Joshs over his idea that all blame/culpability should be eradicated from society (link). This is a common contemporary trope, "Blame/culpability is bad, therefore we should go to the extreme of getting rid of it altogether" (Joshs takes the culturally popular route of saying that everyone is always doing their very best, and therefore it is illogical to blame anyone for anything).

For Aristotle it is never that simple. We can't just run to the extreme and call it a day. Things like blame and anger will involve a mean, and because of this there will be appropriate and inappropriate forms of blame and anger. The key is learning to blame and become angry when we ought to blame and become angry, and learning not to blame and become angry when we ought not blame and become angry.

The is-ought gap objection would go something like this: “it seems as though that one should fulfill their nature does not follow immediately from the fact that one needs to fulfill their nature to achieve happiness; and so it seems as though Aristotle is just appealing to ‘obviousness’ to justify what is good being a thing fulfilling its nature”. — Bob Ross

More simply, the objection asks why one ought to want to be happy. For Aristotle this is sophistry. Humans do want to be happy, just as fish do want to be in the water. It's just the way we are. "We don't necessarily want to be happy," is nothing more than a debater's argument. -

Apustimelogist

946I mean your "criticism" of the modern world is just so insanely reductive view that I could never agree with it. I find these views have a real lack of intellectual humility.

Apustimelogist

946I mean your "criticism" of the modern world is just so insanely reductive view that I could never agree with it. I find these views have a real lack of intellectual humility.

Yes, moral anti-realism is the total reason why an extremely complex, changing world is in a dumpster fire compared to the halcyon days of old (that never really existed) even though the world is ironically probably in a place of greater moral awareness than for the great majority of its history. -

Herg

255

Herg

255

That society is in moral decline is a common illusion (https://www.nature.com/articles/s41586-023-06137-x). Every generation thinks this.Modern society is decaying... — Bob Ross

If you are going to make a case for a change in moral thinking based on the idea that society's morals are in decline, you need to prove that they actually are. I for one don't believe it, and I've been around for over 70 years. There are good, bad and indifferent people in every generation, and that's just how the human race is. -

Count Timothy von Icarus

4.3kIt seems to me that the is-ought gap comes from the modern move to try to collapse practical (and aesthetic) reason into theoretical reason. Arguably, the disconnect is upstream of ethics, in metaphysics. Modern philosophy tends to assume that Goodness and Beauty are not properties of being, while Truth is generally kept in some form (although this gets the axe sometimes too).

Count Timothy von Icarus

4.3kIt seems to me that the is-ought gap comes from the modern move to try to collapse practical (and aesthetic) reason into theoretical reason. Arguably, the disconnect is upstream of ethics, in metaphysics. Modern philosophy tends to assume that Goodness and Beauty are not properties of being, while Truth is generally kept in some form (although this gets the axe sometimes too).

The is-ought gap comes from asking theoretical reason to do practical reason's job. It's a category error from the older perspective; practical reason, whose target is the Good is what motivates us to act. This doesn't work for the modern perspective, which is fundamentaly uncomfortable with conciousness and tries to sequester it. This is because it isn't reducible to mechanism and because this would seem to keep the human sphere "free" as everything else is reduced to mechanism.

This is why so often today you see people trying to define the Good in terms of what people prefer/enjoy. The classical way to look at things would be to say: "people want what is good. When someone does x, they are seeking some good (even if it is a relative or counterfeit good)." Nowadays, you get something like "x is good because people are seeking it."

Why the inversion? It's the elimination or demotion of practical reason. Why people act has to be explained in terms of truth, either the theories of the social sciences or, as often, a mechanistic account based on the natural sciences is desired. Goodness still finds its way in, e.g. the black box of "utility" in economics, but its subservient to theory.

I've never come across the third objection. It seems quite at odds with Aristotle's philosophy. It makes it sound like Aristotle is talking about some "rational agent's" incentives to do whatever maximizes his or her "utility," not unlike Hume. If this were true, the same criticism MacIntyre levels against Hume would hold: "we should be good, pro-social, etc. just in those cases where it benefits us." But for Aristotle happiness always includes other people. Man is the "political animal." Happiness is a life in accordance with the virtues, which in turn precludes narcissism or selfishness.

In the Ethics he talks about the three levels of friendship. It is the first that is narcissistic—being friends with someone for what they can give you. The second stage involves mutual pleasure. The third is enjoying someone due to the good we see in them—enjoying that good for its own sake (there is a clear similarity here with Plato's description of love as "giving birth in beauty" within another). And this sort of non-self interested friendship is key to a good life. "Without a friend no one would want to live, even if possessing all good."

For Aristotle the human good is inextricably bound up in the polis as well.

The most choiceworthy life, on Aristotle’s view, is a pattern of activity that fully engages and expresses the rational parts of human nature. This pattern of activity is a pattern of joint activity because, like a play, it has various interdependent parts that can only be realized by the members of a group together. The pattern is centered on an array of leisured activities that are valuable in themselves, including philosophy, mathematics, art and music. But the pattern also includes the activity of coordinating the social effort to engage in leisured activities (i.e., statesmanship) and various supporting activities, such as the education of citizens and the management of resources.

On Aristotle’s view, a properly ordered society will have an array of material, cultural and institutional facilities that answer to the common interest of citizens in living the most choiceworthy life. These facilities form an environment in which citizens can engage in leisured activities and in which they can perform the various coordinating and supporting activities. Some facilities that figure into Aristotle’s account include: common mess halls and communal meals, which provide occasions for leisured activities (Pol. 1330a1–10; 1331a19–25); a communal system of education (Pol. 1337a20–30); common land (Pol. 1330a9–14); commonly owned slaves to work the land (Pol. 1330a30–3); a shared set of political offices (Pol. 1276a40–3; 1321b12–a10) and administrative buildings (Pol. 1331b5–11); shared weapons and fortifications (Pol. 1328b6–11; 1331a9–18); and an official system priests, temples and public sacrifices (Pol. 1322b17–28).

Aristotle’s account may seem distant from modern sensibilities, but a good analogy for what he has in mind is the form of community that we associate today with certain universities. Think of a college like Princeton or Harvard. Members of the university community are bound together in a social relationship marked by a certain form of mutual concern: members care that they and their fellow members live well, where living well is understood in terms of taking part in a flourishing university life. This way of life is organized around intellectual, cultural and athletic activities, such as physics, art history, lacrosse, and so on. Members work together to maintain an array of facilities that serve their common interest in taking part in this joint activity (e.g., libraries, computer labs, dorm rooms, football fields, etc.). And we can think of public life in the university community in terms of a form of shared practical reasoning that most members engage in, which focuses on maintaining common facilities for the sake of their common interest.[14] -

Count Timothy von Icarus

4.3k

Count Timothy von Icarus

4.3k

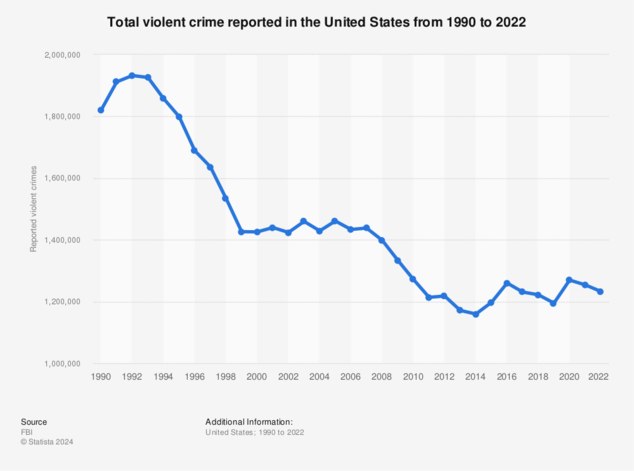

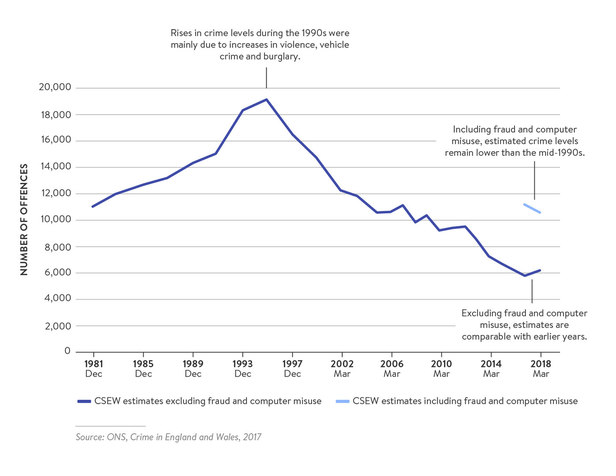

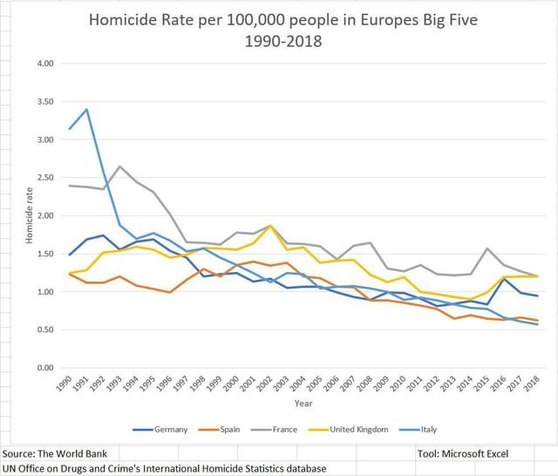

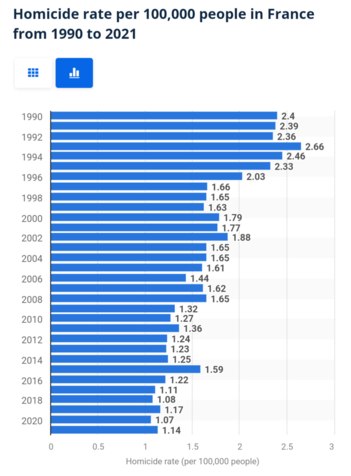

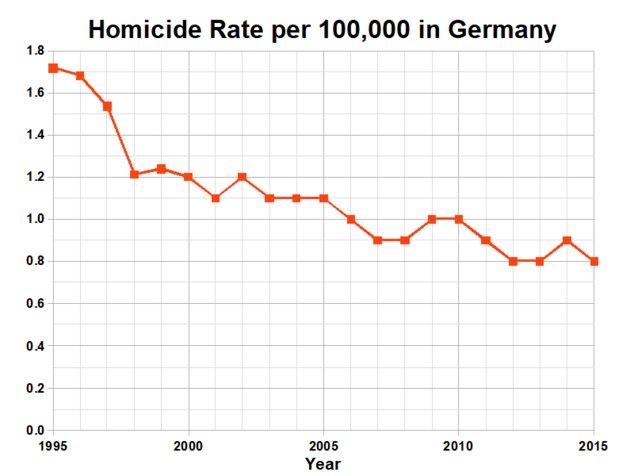

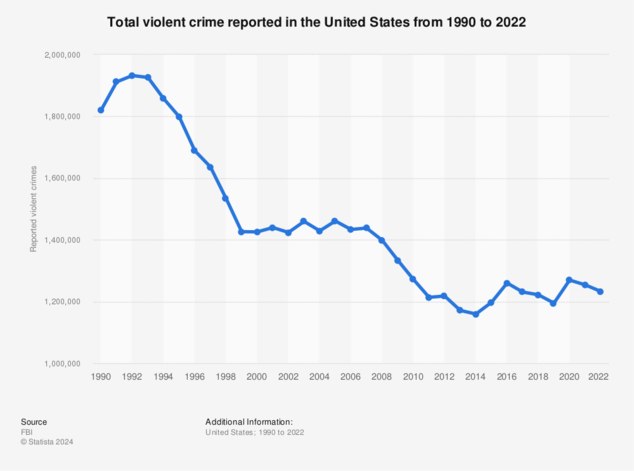

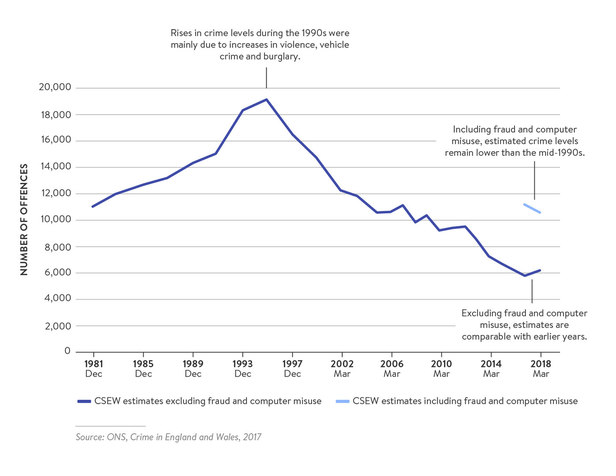

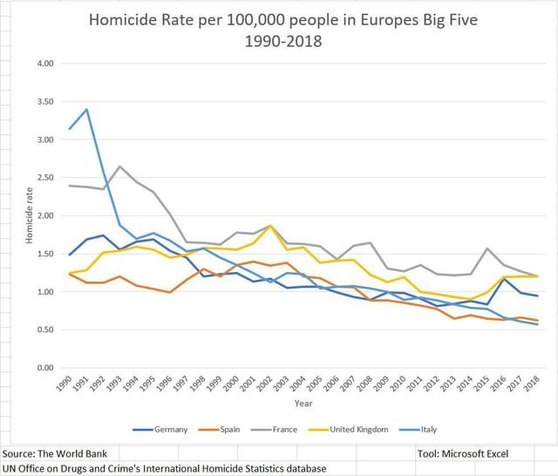

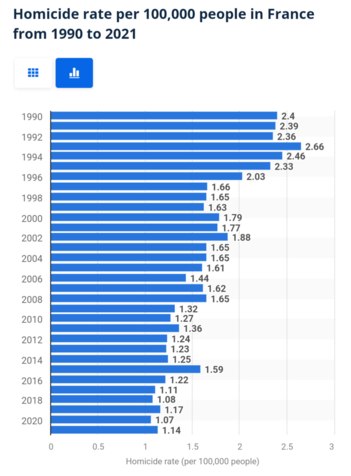

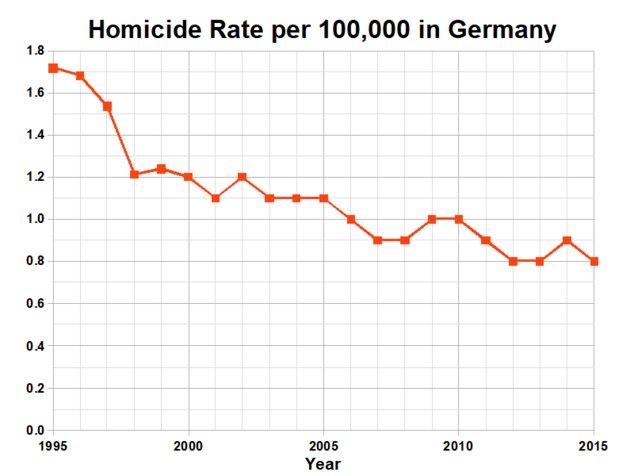

Well this is the big counterpoint to any thesis about modern "moral decay," e.g. MacIntyre's After Virtue. Violent crime is way down in Europe and the US. Wars kill a vastly smaller share of the population than in prior eras. New technologies have offered us all sorts of new opportunities. We each can carry the world's libraries around with us in our pockets, and even have texts read to us at will.

However, I do think this has to be weighed against other factors like the surge in suicides and "deaths of despair," as well as plummeting self-reported well being. Then there is declining membership in pretty much all sorts of social institutions, marriage, etc. Hell, even the age old past time of having sex or being in romantic relationships is plummeting, especially for the young. And then you have the political climate, which at least here in the US is arguably as bad as it has been since the Depression, even if it hasn't been particularly violent (yet...).

Plus, you have the long term moral import of climate change, ocean acidification, etc. hanging over us.

I am less sanguine about "every generation says the world is going to hell." There might very well be some truth to that, but we can look at history and see pretty clearly that sometimes it has gone to hell more in some periods than others. And in each of those occasions, be it the European Wars of Religion or the World Wars, there were warning signs in the sorts of ideologies and world views dominant prior to the cataclysms. Likewise, some of the better times in human history seem to have been supported at least to some degree by the thought of the time, although the influence is obviously always bidirectional here.

My view would tend towards the idea that ethics only has a major affect on the culture writ large when it is instantiated in cultural institutions and public policy (borrowing from Hegel here). Ethics can seem unimportant because it's often only seen as "ethics," when it comes down to the individual level, but policy is ultimately downstream of policymakers ethics. -

mcdoodle

1.1kAristotle emphasises self-love in a way which is sometimes interpreted as narcissism, but that might be a modern preoccupation. If one does not love oneself, in the appropriate Aristotelian way - at the right time for the right reasons - then one's ability to fulfil one's 'ergon' is diminished: personally that seems sound enough to me. He does emphasise the importance of 'philia', which the usual translation as 'friendship' rather mutes, and this is a grounding in a kind of mutuality, an intense friendship with a small group of people, that often gets hurried past.

mcdoodle

1.1kAristotle emphasises self-love in a way which is sometimes interpreted as narcissism, but that might be a modern preoccupation. If one does not love oneself, in the appropriate Aristotelian way - at the right time for the right reasons - then one's ability to fulfil one's 'ergon' is diminished: personally that seems sound enough to me. He does emphasise the importance of 'philia', which the usual translation as 'friendship' rather mutes, and this is a grounding in a kind of mutuality, an intense friendship with a small group of people, that often gets hurried past.

More generally, given your fin-de-siecle opening, I don't understand how you demonstrate that Aristotelian ethics and moral anti-realism are incompatible, which is presumably your aim. The arete/virtues are not represented by Aristotle as factual or everlasting, the arrival at the 'mean' between different extremes is a subtle and nuanced analysis, and the whole approach requires a good society (with a good if unmentioned quota of slaves to do the donkey-work) with education from an early age, to inculcate the habits of virtue. -

Count Timothy von Icarus

4.3k

Count Timothy von Icarus

4.3k

A quick comparison of what clothing is acceptable today and 70 years ago, what sort of lyrics features in mainstream music, and all else shows otherwise. I wasn't around in the 60s, but I don't think children were being exposed to sexual content as extremely often as they are today.

At least in terms of the US I know that the Baby Boomers, on average, lost their virginity earlier than any other generation before or since, had more partners than any other generation, and used drugs more than any other generation. And of course the surge in crime rates starts as they come of age and peaks and then goes into rapid decline as they enter middle age. If anything, the opposite problem exists now. Young people are completely cut off from romantic relationships in many instances.

So, even if the content is a problem, and I'd still argue it is, it certainly isn't the case that it has outweighed other forces in the culture. You might easily argue that digital entertainment has simply become a substitute good for romance, sex, and drugs, and being more affordable you don't need to commit crimes to get all you can consume.

Actually, I'd argue precisely this. A straightforward analysis of "vice indexes" papers over the dire problems. Some young man wasting his life away in isolation playing video games is perhaps in many ways worse off than one who is promiscuous and involved in petty crimes.

That is hardly believable.

Is it? I suppose it depends on what your comparison was. I was thinking over the long term. Attempts to reconstruct the homicide rate of medieval Oxford for instance land well above modern Baltimore today. People seem to always think crime is getting worse, regardless of what actually happens with crime though.

Certainly descriptions of Victorian London are dire enough, hell scapes populated by almost entirely by depraved criminals, no-go zones for the police, etc. It even becomes hard to determine who Jack the Ripper's "canonical victims" are because so many dismembered women are being found around the same area in a short span.

But as for recent history for the most serious crimes, there is a tend downward, although it's most pronounced in the US.

-

Count Timothy von Icarus

4.3k

Count Timothy von Icarus

4.3k

Exactly. Certainly, Nietzsche has been influential. He seems to sell better than any other philosopher today (which is pretty ironic given his elitism). But in the end he is diagnosing an incoherence in Enlightenment ethics, taking them to their logical conclusion. -

Count Timothy von Icarus

4.3k

Count Timothy von Icarus

4.3k

I think Bob is pointing to moral decay, which might itself exist along other elements of positive growth. For example, in A Brave New World we see a picture of a society that would surely get extremely high marks on virtually every metric by which modern technocrats tend to evaluate policy "success." Crime is largely a non-issue, there is no poverty, self-reported well being is surely quite high, and technology has allowed for a great deal of comfort, even largely removing the symptoms of aging. But at the same time it seems fair to say that such a society, despite these positive attributes, has slipped into the direst form of moral and ethical decay.

And there are aspects in which the trajectory of society since Huxley's time has followed his dystopian vision, even as it generally still fails to deliver on at least the "pleasure" part of the equation. -

RogueAI

3.5kI think Bob is pointing to moral decay, which might itself exist along other elements of positive growth. For example, in A Brave New World we see a picture of a society that would surely get extremely high marks on virtually every metric by which modern technocrats tend to evaluate policy "success." Crime is largely a non-issue, there is no poverty, self-reported well being is surely quite high, and technology has allowed for a great deal of comfort, even largely removing the symptoms of aging. But at the same time it seems fair to say that such a society, despite these positive attributes, has slipped into the direst form of moral and ethical decay.

RogueAI

3.5kI think Bob is pointing to moral decay, which might itself exist along other elements of positive growth. For example, in A Brave New World we see a picture of a society that would surely get extremely high marks on virtually every metric by which modern technocrats tend to evaluate policy "success." Crime is largely a non-issue, there is no poverty, self-reported well being is surely quite high, and technology has allowed for a great deal of comfort, even largely removing the symptoms of aging. But at the same time it seems fair to say that such a society, despite these positive attributes, has slipped into the direst form of moral and ethical decay.

And there are aspects in which the trajectory of society since Huxley's time has followed his dystopian vision, even as it generally still fails to deliver on at least the "pleasure" part of the equation. — Count Timothy von Icarus

Civil rights have to rank high on the "moral decay" calculus. I'm definitely not going to agree that any society or time period where gay marriage is illegal, for example, is morally superior to what we have now. That would preclude any time period in the U.S. prior to 2015 from being considered morally superior to the present. -

Count Timothy von Icarus

4.3k

Count Timothy von Icarus

4.3k

Statistics are a tool to be abused by whoever uses them, distorted by whoever makes them.

Yes, you seem to be making that point quite well with the move to religious terrorism, just gun violence in Sweden (also an outlier, and at any rate my home town of 150,000 people had around that many gun homicides in a year plenty of times), and sexual violence, which has indeed been on the rise, although this is generally explained by people being vastly more likely to report it than in prior decades.

As to music, this is sort of comical. I don't think it's possible to get any more sexually explicit than 2 Live Crew's hits like "Pop that Pussy," or something like Notorious BIG's "Unbelievable." White Zombie's 1995 hit single "More Human Than a Human," literally opens with a clip from a porno, and Nine Inch Nails 1994 hit "Closer" was all over the radio when I was growing up. At the very least, MTV's "The Jersey Shore," maxed us out on hedonistic degeneracy many years ago, lol. -

Bob Ross

2.6k

Bob Ross

2.6k

More simply, the objection asks why one ought to want to be happy. For Aristotle this is sophistry. Humans do want to be happy, just as fish do want to be in the water. It's just the way we are. "We don't necessarily want to be happy," is nothing more than a debater's argument.

I think it is a valid question, but Aristotle is on to something. The reason humans want to be happy is because it is the most intrinsically (positively) valuable "thing"...Aristotle just never quite mentions this and starts instead with his idea that what is good is a thing fulfilling its nature. I would say it should be reversed. -

Bob Ross

2.6k

Bob Ross

2.6k

CC: @Count Timothy von Icarus, @Lionino

By “moral decay” I mean that we are in a period of time where morality is being by-at-large supplanted with hyper-individualism; and this leads, as is being seen as it is currently developing in the modern world, to an unstable and bad society.

I can agree with some of the points many of you have been saying (such as that now is arguably the best time to be alive than any point in the past); but I disagree nevertheless that we are still morally progressing. Don’t get me wrong, we have progressed morally throughout history, but now we are starting to go too far and this hyper-extension of individualism and tolerance is causing our societies to rot.

My crude and basic outline of history is as follows:

The first stage is the recognition that there is actual goodness. This is the older time periods mainly marked by the development of religions and older philosophical works (like Aristotle’s and Plato’s).

The second stage is the violent, inhumane, and brutal contest of competing theories of actual goodness. This is the time period of marked by complete intolerance and disregard for human well-being; and lots of torturing, prosecution, and wars (in the name of The Good).

The third stage is humanity learning that this bloody contest is by-at-large not good, and needs to stop. This is when people start looking down upon those who rage wars for the soul purpose of spreading “the word”; torturing people for being of a different religious sect; etc. They start realizing that what humanity has been missing, is that caring about the well-being of other humans is more important than whatever conception of ‘The Good’ one has.

The fourth stage is to disband from this contest and look towards well-being of individuals as most concerning (instead of what is actually good). This is the stage where people start saying things like “even if it is immoral, why do you care? It is not like they are hurting anyone doing it”. This stage starts to lose its sense of why progressing towards ‘The Good’ matters, and starts substituting it for the well-being of living beings.

The fifth stage is the denial of actual goodness altogether, and leads to hyper-individualism and hyper-tolerance. This is the stage where people start transitioning into caring solely about individuals achieving their own desires, so long as it doesn’t impede on other people’s pursuit of theirs, instead of the well-being of people: this is the stage where its it common for people to say “hey, whatever floats your boat: you do you, man”. This is where mental illnesses start being largely unrecognized, because a “normal person” is now viewed as simply “a person that abides by their own desires”; and this is where people start condemning people who try to help other people against their will (for the well-being of that person) as “intolerant”. Likewise, people start losing their sense of “rights” in this stage; and start to see certain obvious violations of rights (such as abortion) as a “grey area”.

The sixth stage is significant losses in happiness, and various unhealthy tendencies are developed in an attempt to counter-act it. We are starting to transition in the modern world to this stage, and its mark is that of active shooters, chronic depression, people butchering their own bodies, substance abuse, sexual self-indulgence, etc. This is stage is the consequence of hyper-individualism leading by-at-large to hedonism which, in turn, leads to a giant void that a person feels like they can never fill as they grow old.

Obviously, history is much more complex than my synopsis here; but I think it suffices.

EDIT:

If we continue down this historical path, then stage seven will more than likely be complete Nietzschien thought: the individual will grow weary and tired of being so superficially happy, will begin losing their sense of respect for other people, and start pursuing their own passions at all expense. This is when the "Ubermensch" would most likely start emerging. -

Outlander

3.2k

Outlander

3.2k

It's probably a reasonable variable that there is a distinct difference in persons who voluntarily complete surveys, versus those who do not.

That is to say, there are countess variables to consider that could reasonably throw any sort of absolute or intrinsically-correct/accurate data out as far as (f)actuality. Note I specifically avoid "usefulness" as that is subjective to those who seek a purpose beyond actual legitimate aggregation of data. -

Leontiskos

5.6kHowever, I do think this has to be weighed against other factors like the surge in suicides and "deaths of despair," as well as plummeting self-reported well being. Then there is declining membership in pretty much all sorts of social institutions, marriage, etc. Hell, even the age old past time of having sex or being in romantic relationships is plummeting, especially for the young. And then you have the political climate, which at least here in the US is arguably as bad as it has been since the Depression, even if it hasn't been particularly violent (yet...). — Count Timothy von Icarus

Leontiskos

5.6kHowever, I do think this has to be weighed against other factors like the surge in suicides and "deaths of despair," as well as plummeting self-reported well being. Then there is declining membership in pretty much all sorts of social institutions, marriage, etc. Hell, even the age old past time of having sex or being in romantic relationships is plummeting, especially for the young. And then you have the political climate, which at least here in the US is arguably as bad as it has been since the Depression, even if it hasn't been particularly violent (yet...). — Count Timothy von Icarus

Right. Political nominees in the last 8 years would also be worth noting.

As to music, this is sort of comical. I don't think it's possible to get any more sexually explicit than 2 Live Crew's hits like "Pop that Pussy," or something like Notorious BIG's "Unbelievable." White Zombie's 1995 hit single "More Human Than a Human," literally opens with a clip from a porno, and Nine Inch Nails 1994 hit "Closer" was all over the radio when I was growing up. At the very least, MTV's "The Jersey Shore," maxed us out on hedonistic degeneracy many years ago, lol. — Count Timothy von Icarus

I don't think these assessments of changes from 1995 to 2024 are really on point. Presumably the OP is thinking far beyond a 30-year period.

But I think the thread has mostly been a distraction. The OP is about Aristotle and the claim that his moral ideas are better than those that prevail in our own time.

Anybody who doesn't know what Bob means by moral decay is simply playing dumb. — Lionino

I agree. -

RogueAI

3.5kModern society is decaying; and this decay is a direct result of moral anti-realism. It is hard to say why moral anti-realism has caught wind like wild fire, but I would hypothesize it is substantially influenced by Nietzschien thought. — Bob Ross

RogueAI

3.5kModern society is decaying; and this decay is a direct result of moral anti-realism. It is hard to say why moral anti-realism has caught wind like wild fire, but I would hypothesize it is substantially influenced by Nietzschien thought. — Bob Ross

It seems you are saying that things have gotten worse/decayed since Nietzsche with the rise of moral anti-realism. But in the 120 years since Nietzsche, we have seen an expansion of civil rights that has been unprecedented. Which pre-1900 societies would you say are morally superior to society now? -

180 Proof

16.5kMaybe you should actually read Nietzsche's writings (especially e.g. BoT, GS, BGE, OtGoM, TotI & EH – preferably W. Kaufmann's translations), Bob, and not just secondary / tertiary derivative sources and polemics against his ideas.

180 Proof

16.5kMaybe you should actually read Nietzsche's writings (especially e.g. BoT, GS, BGE, OtGoM, TotI & EH – preferably W. Kaufmann's translations), Bob, and not just secondary / tertiary derivative sources and polemics against his ideas.

:up:

Welcome to The Philosophy Forum!

Get involved in philosophical discussions about knowledge, truth, language, consciousness, science, politics, religion, logic and mathematics, art, history, and lots more. No ads, no clutter, and very little agreement — just fascinating conversations.

Categories

- Guest category

- Phil. Writing Challenge - June 2025

- The Lounge

- General Philosophy

- Metaphysics & Epistemology

- Philosophy of Mind

- Ethics

- Political Philosophy

- Philosophy of Art

- Logic & Philosophy of Mathematics

- Philosophy of Religion

- Philosophy of Science

- Philosophy of Language

- Interesting Stuff

- Politics and Current Affairs

- Humanities and Social Sciences

- Science and Technology

- Non-English Discussion

- German Discussion

- Spanish Discussion

- Learning Centre

- Resources

- Books and Papers

- Reading groups

- Questions

- Guest Speakers

- David Pearce

- Massimo Pigliucci

- Debates

- Debate Proposals

- Debate Discussion

- Feedback

- Article submissions

- About TPF

- Help

More Discussions

- Other sites we like

- Social media

- Terms of Service

- Sign In

- Created with PlushForums

- © 2026 The Philosophy Forum