-

Philosophim

3.5k

Philosophim

3.5k

Glad I can finally get to replying to your post! First, there is a lot to cover, so I'll post a few answers at a time.

Sorites paradox: When does a heap become a heap?

What we have to understand here is that the word 'heap' is a purely cultural word. It was not invented with any particular amount of grains of sand in mind, only a 'feeling'. As long as two people share that feeling when looking at a pile of sand, they'll both agree its a 'heap'. If one person doesn't feel its a heap, there will be disagreement. The disagreement cannot be boiled down to explicit grains of sand however, but the personal applied feeling of the observed mass.

The problem here is attributing more to the identity than it ever had to begin with. So there is no paradox. Its just a word that is based on a cultural agreement of emotion. Not all distinctive knowledge is precise. We just can't expect precise application out of them.

Hume's problem

If you're referring to the problem of induction, the reasoning which leads to the inductive hierarchy takes care of that.

Karl Poppers Falsification This theory of knowledge is consistent with the idea of falsification. For something to be applied, there must be a scenario that we can imagine if it is misapplied.

Falsification is often misunderstood. It does not mean that, "X is false" or "Its possible that X is false." Its "There is a reasonable imagined possibility where X is false, and we can test it." Lets use an example of a unicorn that is falsifiable, vs one that is not falsifiable.

Non-falsifiable Unicorn - This unicorn has magical powers that hide itself from all detection. They will never let themselves be detected by humans, and will always use their magic to hide themselves from any detectable means.

As you can see, we cannot imagine a scenario to test in which this could be false. No matter our detection results, it will always be an affirmation of the unicorn's existence. There is no imagined scenario that we can test in which the unicorns' existence can be false. As I note in the paper, this would be an inapplicable plausibility, which is just one step above an irrational induction in the hierarchy.

Falsifiable Unicorn - This unicorn has magical powers that make it invisible. However, it cannot hide anything else. You can still hear it, it leaves footprints, etc.

As you can see, we can imagine a testable scenario in which this is false. Can we find horse-like footprints that lead to discovering an invisible creature? If we can't, then the claim is false. This is an applicable plausibility, which is essentially a testable hypothesis.

Thomas Kuhn's paradigms To easily sum his point: Science has a paradigm that remains constant before going through a paradigm shift when current theories can’t explain some phenomenon, and someone proposes a new theory.

This is completely consistent with the knowledge theory proposed here. As we create distinctive knowledge and applicably test it, we are constantly looking to see if the application is contradicted by reality. If it is not, then we assume it to be applicable knowledge, and we can build upon it. For example, lets say we applicably know that the Sun rotates around the Earth. After all, its obvious if we look up at the sky. We build a system of astronomy based on this.

One day, a person discovers that the Earth actually rotates around the Sun! This mind blowing discovery upends everything that was built upon the idea that the Sun rotated around the Earth. We have to go back to this new applicable base, and build from here. It doesn't mean that our previous applicable knowledge wasn't knowledge. For at the time, there was no other reasonable conclusion that could be made. But a reasonable conclusion of today may not be a reasonable conclusion of tomorrow. What we applicably know is a tool that could be invalidated with new information, but it does not invalidate the process of creating and applying distinctive knowledge applicably to reality.

Ship of Theseus Theseus buys a ship, and overtime replaces every piece of the ship due to repairs. At this point, is it still Theseus' ship? Ah, a great example! I have written about this before, it was just had to be cut out to make the original post more manageable.

This thought experiment is not so much one of application, but of how we define the ship. If we define his ship purely by its physical makeup, how detailed should that be? Is it based on the atomic makeup? Because that changes as soon as he buys the ship. So it can't be that detailed, even if we do base it purely on the physical makeup. Is it based on the replacement of one plank? Most would say no. So what is it based on?

Cultural ownership. We agree that there are certain identifiers that indicate ownership. Maybe there's a serial number. A great modern day analogy to this are software licenses. When you purchase software, you are copying from a base software implementation. But it doesn't have to remain a copy. As you save or make alterations to it, its still your program because you have a stable identifier, the license key.

The point though, is because it is cultural, there is no hard and fast rule. We can extend the initial Theseus ship example further. Over the years, Theseus replaces all of his parts, but keeps the old parts in a pile. Someone else comes along and uses all of his original parts to build the ship again. Is the ship of the old parts Theseus ship too? Again, this depends on the culture. Are abandoned old parts owned? Is ownership of something based on who builds it? It is how society that defines it that determines the answer.

Plato's allegory of the cave People in a cave look at the shadows on the wall based on a fire they behind them that they cannot see, and believe the shadows are reality. Looking behind reveals a different truth.

I believe this is covered by my remarks on Kuhn's paradigms. If you need me to go further into it, I will.

Brain in a vat Everything you experience seems real, but in reality its all in your head. The reality is you are a brain in a vat and no nothing of reality outside of your thoughts.

As you can start to glean by now, this is also answered by the theory. Applicable knowledge is what cannot be contradicted. The theory that we are brains in a vat is an inapplicable plausibility. It is impossible to apply, therefore an induction very low on the hierarchy. As such, while it is fun to think about, it is no better than an inapplicably plausible unicorn.

I'm not too familiar with the biblical reference, so I'll pass for now. I think we have enough for now to tackle your other points.

And you also seem to 'misunderstand' me to such a degree, that I wonder if you are able to see me as someone who actually does something very similar to you, in a very rigorous manner, but through a process I might call Indiscrete experience/Inferring. — Caerulea-Lawrence

We are two people with different outlooks in the world. Hopefully through discussion we'll reach a common understanding. Please don't take my disagreement or my viewpoint as looking down or disrespecting yours. You are obviously an intelligent person trying to communicate a world view you see very clearly. Most people think it is simple to convey this experience to others until you have to write it down in a cohesive way. Its much more difficult then we expect!

One interesting thing about Jesus and Platon's cave is 'why would they try to change people's minds?' However, when we look at the interactions, at least between Jesus and the Pharisees, it doesn't look like he understood that they didn't 'get it'. If one person went out of the cave, and had their life changed, why 'wouldn't' the second one do it once told about it? But it seems neither of them were aware of the Typical Mind Fallacy

To me, this is more of a question of inferring, than deduction or induction. It is of course possible to induct in these instances, but you need some kind of 'weighing' process. — Caerulea-Lawrence

This is a question that I have addressed in the past, but never tackled in depth because most people never had the understanding of the base discussion to get this far. This is more theory then, "I have the answer," as I believe we would need to test this to confirm it.

The human brain is amazing not just for its intelligence, but its efficiency. A computer can do more processing for example, but its energy cost shoots through the roof. The fact we can think at the level we do without overheating ourselves or using more energy than we do, cannot be beat. Its easy to forget, but we thinking things that had to evolve in a world where danger and scarcity once existed at much greater levels.

This means we are not innately beings who are situated to think deeply about new experiences, or reorganize thought patterns. Doing so is inefficient. Thinking heavily about something takes concentration, energy, and time. Reprocessing your entire structure of thinking is even more difficult. So when we think about human intelligence, we shouldn't that its a font of reason, but a font of efficient processing.

So then, what does an efficient thinker focus on? Getting a result with as little thought as possible. Too little thought, and you fail to understand the situation and make a potentially lethal or tragic mistake. Too much thought, and you spend an inordinate amount of time and energy on a situation and are isolated from social groups, starve, or miss the window to act.

As such, humans are not wired for excellence, or the ideal. We are wires for, "Just enough". As a quick aside, doing more than "Just enough" is an expression of status. To do more than "Just enough" you must have excessive resources, be remarkably more efficient than others, or in a place of immense privilege. To spend time on inefficient matters and demonstrate mastery over them is an expression of one's status in society.

So then back to your point. One person has a paradigm, or set of distinctive and applicable knowledge that works for their life. They come across another person or group of people that a set of distinctive and applicable knowledge that works for their context. Why should one bother with the other paradigm?

My hypothesis is its about cost vs benefit. Maybe paradigm A is more accurate, but less efficient. Despite being more accurate, it doesn't provide much more benefit than paradigm B which is much more efficient. So society uses paradigm A in special circumstances where more accuracy is needed for a substantial benefit, vs usually using paradigm B for most other cases.

Religion is a great example of this. An atheist might have proof that there is no God, and go to a religion to persuade them to abandon their faith. The atheist may have a more accurate and cohesive world view. But what does the religious group gain? As it is now, they have group cohesion, and a community that cares about one another. They have a higher purpose that motivates them to volunteer and try to make the world a better place. The simple view motivates them and helps them when they're sad and down.

If they decided to take the atheistic standpoint, sure, it might be more accurate. But at what cost? A loss of community and purpose? A loss of motivation to care about others? People do not fight for the truth. They fight for the good that a certain viewpoint provides for their lives. If reality lets them have this viewpoint and benefits with few contradictions, why change?

Perhaps this is part of the 'intuition' you speak about. It is a mistake to think that our thought processes are for logic and truth. They are for efficient benefits to ourselves and society. And sometimes we can't voice that, but its there, under the surface.

I'll let this rest for now. What do you think about the topics? is starting to touch the surface of what you're thinking about, or is there another direction we need to go? I appreciate your thoughts. -

Treatid

54These can be boiled down to stillness and motion. The stillness of objects is sustained against the motion of relationships. Motion is as ubiquitous as the stillness it moves against and neither objects nor stillness nor relationships nor motion is first, or last, or the essence, or the true being. Because they are all at once in the paradox, which is the being, the substance, the related ones. — Fire Ologist

Treatid

54These can be boiled down to stillness and motion. The stillness of objects is sustained against the motion of relationships. Motion is as ubiquitous as the stillness it moves against and neither objects nor stillness nor relationships nor motion is first, or last, or the essence, or the true being. Because they are all at once in the paradox, which is the being, the substance, the related ones. — Fire Ologist

Beautiful. I would be interested in an expansion of your concept of 'paradox'. Context makes it appear relevant and I can see several ways in which our understanding of our own existence and communication could evoke chicken and egg notions of precedence.

Otherwise, you point is well made and taken.

So it doesn’t matter whether we’re talking about seeing object and their relations or just relations of relations, the epistemic meaning of the sense data we perceive is dependent on the nature of our conceptual schemes. Do you agree with this? — Joshs

I haven't previously come across Wilfred Sellars. I've has a quick dash through some summaries and added him to my reading list.

I strongly agree that perception and thought are intimately connected.

For the rest, I'm concerned you are asking me if I'm still beating my wife. In reading the question I have the feeling I'm being asked to agree to a conceptual framework.

Specifically, I think that everything is an aspect of a singular whole. I can perceive differences between senses, thought and language, and in a casual conversation I'd readily accept the distinctions. But in the midst of constructing philosophical foundations I'm much more reluctant to make an implicit agreement that epistemic knowledge is not just an aspect of conceptual schemas.

Further, I think language is primarily proscribed by the nature of the universe. While there are cultural influences, the core mechanism of language is not culturally dependent. In practise, almost nobody uses formal logic in everyday conversation.

As such, I question the premise that particular conceptions of how language function have a significant impact compared with the actual mechanisms of language.

My point is that we can invent an infinite number of distinctive ways of viewing and analyzing the world. The proof comes in its application. I hope this lengthy reply answered your questions and added a little more clarity to my points. Let me know what you think! — Philosophim

I'm liking your approach the more I play/argue with it. My specific argument regarding objects/relationships is misguided. More details below but as a gist - I still feel there are hidden assumptions in your statements that run the risk of invalidating parts.

Course correction

- My argument between objects and relations is mis-focused. You are right that it doesn't matter whether a given perception is illusion.

- I'm actually arguing against impossible assumptions. My perception is that there is one large multifaceted assumption that is impossible.

- Description has a mechanism. Some things can be described. Some things cannot be described.

Mistaken assumption

It is widely assumed that it is possible to describe an object.

This is wrong. It is a futile effort.

The Integer 1

The integer 1 has a set of relationships with the integer 2. Likewise for 3, 4, one million, -69, an apple,...

All these relationships form a pattern. This pattern is our conception of what the integer 1 is.

With many interconnected relationships we have a compelling sense of what something is.

If we were to remove each relationship to get to the essence of 1... we would eventually find we are left with nothing.

The integer 1 is the set of relationships it has with everything else. The integer 1 outside our universe with no relationships to anything is indistinguishable from nothingness.

Descriptions

A description is a network of relationships.

The mechanism of language is to build a network of relationships.

Essence

The typical process for finding the essence of meaning, significance, etc; is to strip away all the miscellaneous chaff until we are left with the essential core of the thing we are examining.

This is why this mistaken assumption is so devastating to the pursuit of knowledge.

Every philosophical, mathematical and physical discussion that tries to get to the core of a matter by stripping away all the extraneous concepts, assumptions and frippery is dooming itself to futility.

This is my argument

The assumption that meaning, significance or what have you, is an essential quality of a thing is the single greatest mistake of modern thought.

The significance of a thing is the sum total of its relationships with everything else. Remove the relationships and you have nothing.

This illusion is only here in distinction from some other that (which other can be an illusion as well, or anything, as in comparison to “this” particular illusion, the other need only be a “that”.) — Fire Ologist

I would hate to put words in your mouth - but your post screams to me that you already see this. You already know that every "this" needs all those "thats" in order to have significance.

Is it true?

Is language the process of creating relationships? Yes.

Read a dictionary. Examine those definitions. A simple empirical verification.

For a really fun time, consider the equations of Quantum Mechanics. An equation is a network of relationships.

Every mathematical equation is a little (or large) network of relationships.

It doesn't matter what the essence of the integer 1 is. It was never relevant. What we manipulate and use is the network of relationships. -

Caerulea-Lawrence

26Hello @Philosophim

Caerulea-Lawrence

26Hello @Philosophim

I appreciate the extensive elaboration on the various philosophical problems I mentioned. I won’t delve into them too much, just want to give a thanks for the thought and effort, and say that it was a useful read.

And you also seem to 'misunderstand' me to such a degree, that I wonder if you are able to see me as someone who actually does something very similar to you, in a very rigorous manner, but through a process I might call Indiscrete experience/Inferring. — Caerulea-Lawrence

We are two people with different outlooks in the world. Hopefully through discussion we'll reach a common understanding. Please don't take my disagreement or my viewpoint as looking down or disrespecting yours. You are obviously an intelligent person trying to communicate a world view you see very clearly. Most people think it is simple to convey this experience to others until you have to write it down in a cohesive way. Its much more difficult then we expect! — Philosophim

No worries, words and feelings won’t hinder me in diving deep. It is true that I am much more skilled at other ways of understanding and knowledge than methodical conveyance of my experience, but I find these interactions with you useful.

The human brain is amazing not just for its intelligence, but its efficiency. A computer can do more processing for example, but its energy cost shoots through the roof. The fact we can think at the level we do without overheating ourselves or using more energy than we do, cannot be beat. Its easy to forget, but we thinking things that had to evolve in a world where danger and scarcity once existed at much greater levels.

This means we are not innately beings who are situated to think deeply about new experiences, or reorganize thought patterns. Doing so is inefficient. Thinking heavily about something takes concentration, energy, and time. Reprocessing your entire structure of thinking is even more difficult. So when we think about human intelligence, we shouldn't that its a font of reason, but a font of efficient processing.

So then, what does an efficient thinker focus on? Getting a result with as little thought as possible. Too little thought, and you fail to understand the situation and make a potentially lethal or tragic mistake. Too much thought, and you spend an inordinate amount of time and energy on a situation and are isolated from social groups, starve, or miss the window to act.

As such, humans are not wired for excellence, or the ideal. We are wires for, "Just enough". As a quick aside, doing more than "Just enough" is an expression of status. To do more than "Just enough" you must have excessive resources, be remarkably more efficient than others, or in a place of immense privilege. To spend time on inefficient matters and demonstrate mastery over them is an expression of one's status in society. — Philosophim

These are some very good points, so I’ll just go directly into bouncing off them. Despite the apparent success of our intelligence, and the importance of efficiency, I believe focusing on that might conflate cause and effect. We don’t have intelligence because it is ‘necessary’, we have intelligence as it coincides with the survival and procreation in the specific niche we humans fill. I’m not saying that as an expert at evolutionary biology, it is just that if you look at your argument, viruses, bacteria, amoeba and parasites achieve the same goals; survival and procreation, as us humans, despite having far, far lower intelligence. In a way, for what they achieve, they are miles ahead of us in efficiency, but they do not beat us at complexity in organization.

So then back to your point. One person has a paradigm, or set of distinctive and applicable knowledge that works for their life. They come across another person or group of people that a set of distinctive and applicable knowledge that works for their context. Why should one bother with the other paradigm?

My hypothesis is its about cost vs benefit. Maybe paradigm A is more accurate, but less efficient.[...] — Philosophim

If they decided to take the atheistic standpoint, sure, it might be more accurate. But at what cost? A loss of community and purpose? A loss of motivation to care about others? People do not fight for the truth. They fight for the good that a certain viewpoint provides for their lives. If reality lets them have this viewpoint and benefits with few contradictions, why change?

Perhaps this is part of the 'intuition' you speak about. It is a mistake to think that our thought processes are for logic and truth. They are for efficient benefits to ourselves and society. And sometimes we can't voice that, but its there, under the surface — Philosophim

I’ll try to weave this together as best I can. To bring back the word you talked about in your elaborations from earlier, ‘culture’( as a contrast to ‘natural’ and ‘reality’). But, to modern humans, our ‘reality’ is now influenced heavily by other humans. And so, reducing ‘culture’ to being only something abstract, I believe, will might make it harder to understand why there are paradigms, and what role they play. The thing is, some people Do fight for the truth, despite the cost to their own lives. Humans as a species is very diverse, and I do not believe cost vs benefit alone fits the diversity we see in paradigms. What I believe fits better is that we are born with a predisposition to different paradigms, and are drawn to them like moths to the flame.

I find your description of ‘efficiency’ very relevant too. Efficiency is the metric by which you measure success by, but What success Is, in other words, what you measure, is defined by your paradigm. So why do we have different paradigms when you can be perfectly happy in a small hunter-gatherer ‘family’, or in a bigger tribe? And if the explanation is «We developed new paradigms to make sense of problems that no longer made sense with the explanations available», doesn’t the argument itself clash with reality. «We» have also worked tirelessly to avoid changing paradigms, to fight against it, to go so far as to murder, imprison or silence those that think differently. Moreover «we» still live and die as hunter-gatherers. One view of paradigms is a kind of trait that differentiates humans in what specific problems they see, try to fix, with which tools, how, why and with whom.

—

Knowledge-generation and creation itself doesn’t seem random, and paradigms are the overaching theme that fill in part of the void of why people consistently choose different types of inductions when it comes to some part of reality/culture, but do not apply that elsewhere. And abundance of resources does explain how people are able to focus so much energy on that, but abundance in itself doesn’t lead to paradigm-creation, or to people choosing a new paradigm. There are other forces at play.

—

Seems like we are diverging from the original point you have made about Knowledge and Induction. This is something I see as the backdrop to your method, and why it works much more specifically than I would prefer it to. And I'm not that much closer to inference, either. Maybe it is because it is a 'relational' method, and fuels on interaction with others, and not on introspection or reflection alone. Hm, that is an important point. Will add it to my repository.

How does this land with you/comes up in you? -

Philosophim

3.5kI'm actually arguing against impossible assumptions. My perception is that there is one large multifaceted assumption that is impossible. — Treatid

Philosophim

3.5kI'm actually arguing against impossible assumptions. My perception is that there is one large multifaceted assumption that is impossible. — Treatid

If I understand what you're saying, I agree. I once sat down and asked myself, "If this is correct, what would knowing the truth be?" I realized the only way to know truth, which is what is real, would be to have observed and experienced something from all possible perspectives and viewpoints, and an understanding of all conclusions which did not contradict themselves (as well possibly the ones that do!).

It is an absolutely impossible endeavor.

Description has a mechanism. Some things can be described. Some things cannot be described. — Treatid

Also very true. The knowledge system I've proposed here is not limited to linguistic thought. If I had a image, or even a feeling about a specific situation, that can be logged as a memory which then is applied in the future.

For example, the emotion of 'dread'. While we might be able to objectively ascertain that people experiencing dread have some common physical tells, that doesn't mean it describes the individual feeling the person is experiencing. While an individual can know if they're experiencing dread by the emotions they are currently having, being able to know if another person is experiencing that same emotion, despite physical tells, is only available to that specific person. We cannot experience what another experiences.

We can get around this in some ways through creating distinctive and applicable contexts. For example, if someone is blind, we cannot use the word, "See" in the same way. Telling a blind person, "Do you see the point?" will have a difference concept. We don't mean "visually observe", but mean, "Understand".

Two people who lift weights in a gym may have a different conceptions of weak. A person who regularly benches 200 pounds may believe a bench of 150 is weak for them. A person who regularly benches 100 pounds may believe someone who benches 150 is strong relative to them. They generally solve this discrepancy when talking to each other by entering into a common context. For example, the weak person, who is friends with the strong, may make a joke about how the strong person is being a wimp for only lifting 180 pounds that day, encouraging them to lift more. The strong person may yell excitedly and get hyped that the weak person is pushing past what they normally do and lifts 110 pounds that day.

It is widely assumed that it is possible to describe an object.

This is wrong. It is a futile effort. — Treatid

It depends on your definition of 'describe'. If I describe a lemon as a yellowish sour fruit, its a description is it not?" When we say that things are impossible, we have to be very specific as you also realize that language and meaning can be very indefinite unless we make it so.

If we were to remove each relationship to get to the essence of 1... we would eventually find we are left with nothing.

The integer 1 is the set of relationships it has with everything else. The integer 1 outside our universe with no relationships to anything is indistinguishable from nothingness. — Treatid

That is one way to describe it, but I can describe a scenario that counters that. The integer "1" is really a representation of our ability to discretely experience. "One field of grass. One blade of grass. One piece of grass." We can discretely experience anything. Not just parts but everything. The discrete experience of "Existence". A sensation in which there is nothing else but the experience itself. No breakdowns, no parts, no relation. It is within this that relation forms when we create parts. But the experience of the whole, of being itself, is one without relation.

A description is a network of relationships.

The mechanism of language is to build a network of relationships. — Treatid

I agree that between more than one person, a description is a network of relationships. It is because we are establishing a common ground between our individual experiences to establish a base of distinctive knowledge and application (context) that we can reasonably and logically apply with each other.

The typical process for finding the essence of meaning, significance, etc; is to strip away all the miscellaneous chaff until we are left with the essential core of the thing we are examining.

This is why this mistaken assumption is so devastating to the pursuit of knowledge.

Every philosophical, mathematical and physical discussion that tries to get to the core of a matter by stripping away all the extraneous concepts, assumptions and frippery is dooming itself to futility. — Treatid

Who determines what is extraneous, an assumption, or frippery? Between one group of people, certain aspects may be important, while between another group of people, it is not. But what is deemed frippery is dismissed within logical language in both groups A and B, even if they have different views of what is not important. The only hard counters are if there is contradictions that result when each group's contextual distinctive context is applied to reality.

Example: Group A believes that goats can only have brown hair, and white haired 'goats' are sheep.

Group B believes that goats can only have white hair, and that brown haired 'goats' are sheep.

The contradiction comes into play if group A and B meet each other. They can either say the other's contexts are wrong, change their contexts to adapt to each other, or form an entirely new C context that they only use when talking between the groups, but reverting back to A or B when with 'their people'.

What you've missed is that we are the one's who determine was is essential and non-essential in the definitions that we create. So its not impossible to make a description. Its not impossible to create words that strip away other observations until there is a central core. We just have to agree what is essential and non-essential when establishing context and conversation.

The assumption that meaning, significance or what have you, is an essential quality of a thing is the single greatest mistake of modern thought.

The significance of a thing is the sum total of its relationships with everything else. Remove the relationships and you have nothing. — Treatid

The mistake is to think that one group's idea of what is the essential quality of a thing is that it is true. Ignoring the relationships between people, society, and history to create a context is wrong. But it is also wrong to think that we cannot apply such things logically after established. We may have a society that has established that houses made of paper are the strongest houses until another person introduces the concept and application of a brick house. Societal contexts can only reasonably hold if reality does not contradict them.

Remove the relationships, and what you've removed is societal context. But you have not removed yourself or the logic that any memory you apply has the plausibility of being contradicted by reality.

So, well said and stated! I agree with a lot of your initial premises, but I'm tweaking them within the bounds of the theory to demonstrate that we can come to different conclusion that still allow us logical arguments, and 'objective' measurements despite our relationships. -

Philosophim

3.5kI appreciate the extensive elaboration on the various philosophical problems I mentioned. I won’t delve into them too much, just want to give a thanks for the thought and effort, and say that it was a useful read. — Caerulea-Lawrence

Philosophim

3.5kI appreciate the extensive elaboration on the various philosophical problems I mentioned. I won’t delve into them too much, just want to give a thanks for the thought and effort, and say that it was a useful read. — Caerulea-Lawrence

You're welcome! And I got the alert that you replied this time. :D

Despite the apparent success of our intelligence, and the importance of efficiency, I believe focusing on that might conflate cause and effect. We don’t have intelligence because it is ‘necessary’, we have intelligence as it coincides with the survival and procreation in the specific niche we humans fill. I’m not saying that as an expert at evolutionary biology, it is just that if you look at your argument, viruses, bacteria, amoeba and parasites achieve the same goals; survival and procreation, as us humans, despite having far, far lower intelligence. In a way, for what they achieve, they are miles ahead of us in efficiency, but they do not beat us at complexity in organization. — Caerulea-Lawrence

Very true. It has been argued that our intelligence evolved out of our social nature. The understanding of complex and dynamic situations has spilled into other areas of our brains allowing us to analyze complex relationships outside of social situations.

The thing is, some people Do fight for the truth, despite the cost to their own lives. Humans as a species is very diverse, and I do not believe cost vs benefit alone fits the diversity we see in paradigms. What I believe fits better is that we are born with a predisposition to different paradigms, and are drawn to them like moths to the flame. — Caerulea-Lawrence

I don't disagree with your assessment. I think its an equally valid viewpoint. I could sit here and say, "Yes, but fulfilling that predisposition is for their personal benefit," but that's unnecessary. There is a compulsion among individuals and groups that certain viewpoints of the world this fit our outlook better. And I do believe some outlooks are better by fact, only because they lead to less contradictions and overall benefits for the society. A society that relies on logic, science, and fairness is going to be better off than a society that relies more on wishful thinking, superstition, and abuse of others.

So why do we have different paradigms when you can be perfectly happy in a small hunter-gatherer ‘family’, or in a bigger tribe? And if the explanation is «We developed new paradigms to make sense of problems that no longer made sense with the explanations available», doesn’t the argument itself clash with reality. — Caerulea-Lawrence

I believe that is one reason people change paradigms, but there can be others. I find religion to be an interesting paradigm that can persist in the modern day world. While religions often have logical holes or contradictions purely from a rational viewpoint, as I've mentioned earlier, they provide a sense of community, purpose, and guide that are often invaluable and not easily replaced by abandoning the precepts. Even though the modern day world can explain multiple things in ways that do no require divinity, a divine interpretation of the world can largely co-exist beside it in a truce of sorts if societal rules are established properly. Separation of church and state for example.

I believe the greatest motivator is, to your point, a paradigm that fits within what an individual or group is most inclined towards. As long as reality does not outright contradict the goals of the group, it is acceptable and often times protected from outside criticism.

Seems like we are diverging from the original point you have made about Knowledge and Induction. — Caerulea-Lawrence

No, I believe we are building upon it into the next steps. I wrote a follow up on the third post that includes societal context if you have not read it yet. The original post did not include societal context, as the initial post about the knowledge process of a singular individual is enough to wrap one's head around initially. If you haven't read that section yet, feel free as it might help with the current subject matter we're discussing at this moment. Fantastic points and thought Caerulea! -

Treatid

54If I understand what you're saying, I agree. I once sat down and asked myself, "If this is correct, what would knowing the truth be?" I realized the only way to know truth, which is what is real, would be to have observed and experienced something from all possible perspectives and viewpoints, and an understanding of all conclusions which did not contradict themselves (as well possibly the ones that do!).

Treatid

54If I understand what you're saying, I agree. I once sat down and asked myself, "If this is correct, what would knowing the truth be?" I realized the only way to know truth, which is what is real, would be to have observed and experienced something from all possible perspectives and viewpoints, and an understanding of all conclusions which did not contradict themselves (as well possibly the ones that do!).

It is an absolutely impossible endeavor. — Philosophim

Impossible to reach omniscience - yes. But partial understanding is better than no understanding.

We are agreeing with each other so hard here it makes me wonder how we can possibly diverge elsewhere.

Yes - truth/knowledge is the full understanding of all possible contexts. We can endeavour to approach this limit knowing we will never reach it but can come arbitrarily close.

For example, the emotion of 'dread'. While we might be able to objectively ascertain that people experiencing dread have some common physical tells, that doesn't mean it describes the individual feeling the person is experiencing. While an individual can know if they're experiencing dread by the emotions they are currently having, being able to know if another person is experiencing that same emotion, despite physical tells, is only available to that specific person. We cannot experience what another experiences. — Philosophim

Again - so much yes.

Except I would cast the net much wider. Do other people experience the colour 'red' in the way that you do? This is standard philosophical fare.

I want to take it further. Apply this to everything. Your perception of the world is rooted in your experience of the world.

I think your description of 'Dread' applies to every concept that we can feel, experience or think.

Rain is a common experience and by sharing our experiences we come to regard the experience of rain as being objective - something that everyone experiences in the same way. However your description of 'dread' applies to my experience of 'rain'.

You've talked about taking shortcuts where we don't want to build everything from first principles just to say hello to the neighbour...

Shortcuts are fine, even necessary, but they are a convenient approximation.

When doing a deep dive into philosophical knowledge we are liable to find ourselves led astray if we rely on the shortcuts as being fundamental in, and of, themselves.

It depends on your definition of 'describe'. If I describe a lemon as a yellowish sour fruit, its a description is it not?" When we say that things are impossible, we have to be very specific as you also realize that language and meaning can be very indefinite unless we make it so. — Philosophim

Yeppity yep.

That is one way to describe it, but I can describe a scenario that counters that. The integer "1" is really a representation of our ability to discretely experience. "One field of grass. One blade of grass. One piece of grass." We can discretely experience anything. Not just parts but everything. The discrete experience of "Existence". A sensation in which there is nothing else but the experience itself. No breakdowns, no parts, no relation. It is within this that relation forms when we create parts. But the experience of the whole, of being itself, is one without relation. — Philosophim

Here we part ways.

You purport to demonstrate that we consider '1' discretely.

I'm looking at your description and seeing you describe '1' using a bunch of explicit and implicit relationships.

"A blade of grass" is very different to "A field of grass".

Scenario

You sit down to read a book. The first page contains the word 'one':

"one"

And that is it. That is the entire book.

You understand 'one'. The word has some meaning for you. But simple stating the word 'one' doesn't expand your knowledge. No new information has been conveyed.

To convey information you must put that 'one' into some context - some set of relationships with other words.

Moreover

Compare your argument here with the first paragraph of your post.

As I read these two sections I see a disconnect. You are contradicting yourself. You are arguing two distinct contradictory positions. In the first paragraph you argue for the importance of context, in the latter paragraph you are arguing that we can consider things without context.

Society's mistake

I strongly suspect that this inconsistency is systemic.

Everyone knows that context is important to understanding a given sentence. At the same time, everyone knows that there is a fixed definition of the words they are using and "you are using the wrong definition".

The idea of meaning being dependent on context isn't new or surprising in any way.

And then we have everyone from philosophy through mathematics to physics arguing that there are inherent truths independent of context.

Agreement

Your first paragraph is a beautiful statement of understanding.

You obviously understand that full knowledge (truth) requires all the contexts.

This is my proposal. This is where I think we can make progress as philosophers and as humans. This is where the pursuit of knowledge lies. This is the path to all possible understanding. True, we can't reach the limit - but we can approach that limit.

The flip side

Despite this clear understanding, Everybody and their dog suddenly starts insisting that knowledge, truth, meaning, ... are inherent properties independent of context.

This isn't a rational position. It is a direct contradiction of our direct experience of the importance of context.

Even after making the clearest statement of meaning/truth/significance I have ever seen; you flip around to arguing for inherent meaning just a few paragraphs later.

It is a potentially fascinating study to see why the myth of a reductive approach to knowledge persists despite the direct evidence of the importance of context. However, my immediate goal is to make this inconsistency explicit.

Reductive vs Expansive

I'm picking on your inconsistency; but that inconsistency is representative of the entirety of modern thought. The reductive approach to knowledge is exactly the wrong direction.

Read your first paragraph and bask in its glory. Greater knowledge, understanding, truth, ... comes through greater inclusion.

Each piece of context you remove takes you further away from knowledge. Every extra piece of context takes you closer to knowledge.

You have defined what knowledge is. Commit to that definition. Be consistent in your use of that definition. -

Joshs

6.7k

Joshs

6.7k

You obviously understand that full knowledge (truth) requires all the contexts.

This is my proposal. This is where I think we can make progress as philosophers and as humans. This is where the pursuit of knowledge lies. This is the path to all possible understanding. True, we can't reach the limit - but we can approach that limit. — Treatid

I’m wondering how far you’re willing to push the role of context in relation to the progress of knowledge. I’d like to we you push it to the limit. That means socorro’s g he idea that knowledge is the matching of our concepts to a world independent of our schemes. Context is critical because both we and our world are in continual motion. We have a system of constructs that are organized hierarchically into subordinate and superordinate aspects such that most new events are easily subsumed by our system without causing any crisis of inconsistency. When we embrace new events by effectively anticipating them, our system doesn’t remain unchanged but is subtly changed as a whole by the novel aspects of what it encounters. The world as I perceive it is already shaped by my construct system, so it is not the same objective world for everybody. What appears consistent or inconsistent, true false , harmonious or contradictory, is not the result of a conversation between subjects and a recalcitrant, independent reality, but a reciprocation in which the subjective and the objective poles are inextricably responsive to, and mutually dependent on each other. -

Philosophim

3.5kImpossible to reach omniscience - yes. But partial understanding is better than no understanding.

Philosophim

3.5kImpossible to reach omniscience - yes. But partial understanding is better than no understanding.

We are agreeing with each other so hard here it makes me wonder how we can possibly diverge elsewhere. — Treatid

Likely its in our definition differences. Even if we use similar words, there may be personal context to those words that results in us drawing different conclusions. The most important thing to find agreement on in a discussion like this is the definitions themselves. We are two different minds with unique backgrounds coming together. It takes some time to learn what each other intends by our words.

I want to take it further. Apply this to everything. Your perception of the world is rooted in your experience of the world.

I think your description of 'Dread' applies to every concept that we can feel, experience or think — Treatid

Within our own personal context, this is true. I can never know what its like to be another person. That doesn't mean I can't conclude other people exist, or that they and I cannot come to a common understanding of the way we both experience the world. Coming to a common understanding requires finding the things which are uncontroversial between us, while generally dismissing the rest as non-essential variety.

Rain is a common experience and by sharing our experiences we come to regard the experience of rain as being objective - something that everyone experiences in the same way. However your description of 'dread' applies to my experience of 'rain'. — Treatid

Again, it all comes down to contexts. What is the context of rain that is personal to you vs personal to me? I'm sure when I envision rain I have a different memory then you. So we likely can't relate on that context. But we can find common ground. Water percipitates in the clouds and falls to the ground. You and I both understand what that means. We can apply that definition to reality. If we did it together, maybe we would share some more common emotions like both finding the rain cool. Or maybe you would find it hot, I would find it cold, and we would get a good laugh out of it.

That is why society builds certain rules of measurement that do not rely on personal experience. They are abstracts. Meters for length. Liters for volume. Words that fit both an efficient general sense like 'tree', and more descriptive and specific words like Sycamore.

You've talked about taking shortcuts where we don't want to build everything from first principles just to say hello to the neighbour...

Shortcuts are fine, even necessary, but they are a convenient approximation.

When doing a deep dive into philosophical knowledge we are liable to find ourselves led astray if we rely on the shortcuts as being fundamental in, and of, themselves. — Treatid

Perfectly correct. For the build up of knowledge specifically, I noted specific rules to follow. And in cases where knowledge is not possible, or in the quest to build up knowledge, we have a hierarchy of inductions we can follow for cogent thinking. If you feel I'm not being specific enough or taking a short cut where its not needed, feel free to point it out! I will get as detailed and specific as needed.

Here we part ways.

You purport to demonstrate that we consider '1' discretely.

I'm looking at your description and seeing you describe '1' using a bunch of explicit and implicit relationships. — Treatid

Right, I've already noted there is nothing against defining something in relation to another discrete experience. The point I have tried to make is that one can have the discrete experience of everything. What allows us to create relations is memory. I have to remember that I focused on something else just a few seconds ago to compare. I think that's where I've missed the mark in what I've been trying to communicate. Discrete experience is the act of simple focus. We need memory of our discrete experiences to form and process relationships.

You sit down to read a book. The first page contains the word 'one':

"one"

And that is it. That is the entire book.

You understand 'one'. The word has some meaning for you. But simple stating the word 'one' doesn't expand your knowledge. No new information has been conveyed.

To convey information you must put that 'one' into some context - some set of relationships with other words. — Treatid

But first comes 'the book'. The focus. With memory, we can create comparisons. With memory we can relate. With memory, we can create words to recall and apply later.

As I read these two sections I see a disconnect. You are contradicting yourself. You are arguing two distinct contradictory positions. In the first paragraph you argue for the importance of context, in the latter paragraph you are arguing that we can consider things without context. — Treatid

What I am doing is trying to break down complex concepts into more simple and easier to comprehend ideas. People think better when you can get down to fine grained foundations, and build on top of them. So we have discrete experience + memory + comparison between memories = relationships. If everything is a relationship, then what do we call a thinking thing that can discretely experience, but has no memory of it? A camera taking a snapshot and processing it to paper without ever knowing any relation to what it is doing.

And then we have everyone from philosophy through mathematics to physics arguing that there are inherent truths independent of context. — Treatid

It depends again on what they mean by context. Oftentimes context is applied to 'subjective context'. But there is 'objective context' as well. People are oftentimes efficient in language, and leave lots of implicit implications in which get lost as they filter out into the general population, or even over time. Its our job as philosophers and thinkers to bring it back every so often. :)

If you doubt that there is an objective context, how is it that almost all human beings of a particular intelligence are able to learn that 1+1 = 2? How do we all learn that if we stop breathing, we'll die? I do not deny that there are contexts formed between every single person and subgroup you meet. But their existence co-exists within a created objective context of measurement and identification of reality. It does not undermine it, even if it wants to.

You obviously understand that full knowledge (truth) requires all the contexts.

This is my proposal. This is where I think we can make progress as philosophers and as humans. This is where the pursuit of knowledge lies. This is the path to all possible understanding. True, we can't reach the limit - but we can approach that limit. — Treatid

100% agree! I hope you understand that while I may have some counter points to consider, it does not mean I am not considering your viewpoint carefully. It is refreshing to have a conversation with someone who is interested in a good discussion.

Despite this clear understanding, Everybody and their dog suddenly starts insisting that knowledge, truth, meaning, ... are inherent properties independent of context.

This isn't a rational position. It is a direct contradiction of our direct experience of the importance of context.

Even after making the clearest statement of meaning/truth/significance I have ever seen; you flip around to arguing for inherent meaning just a few paragraphs later. — Treatid

Hm, I did not intend to imply there was inherent meaning. There are contexts that apply beyond our individual subjective viewpoints that are the collective context of rational agents. And many times when communicating with one another, we need certain clear and fixed essential commonalities to those words or phrases, or else we will, "miss the mark" if you get my meaning.

We are not really disagreeing much, if at all, in the big picture. The purpose of the paper is to take that common picture that we see, and put it into words that can be communicated effectively and consistently to several people. I know there are several people who believe both in parts and relationships. Does a break down of the act of discrete experience, memory, and the interplay between them forming relationships make it more palatable to you? It may not perfectly coincide, but do you think it can be more easily communicated to others who don't think like us? The world is full of people who found out knowledge, but were unable to communicate it in a way that a majority could agree with and use effectively.

Each piece of context you remove takes you further away from knowledge. Every extra piece of context takes you closer to knowledge. — Treatid

I agree with you, but one minor detail. "It takes us closer to complete knowledge". To build, we must start with a basic definition of knowledge in the barest sense. Something you may not have considered yet, is the theory I've proposed here can potentially be applied to non-human intellects. Dogs, computers, the process would be the same. Thus something could be said to applicably know X within its context, while if one has been challenged through multiple contexts, one can only applicably know Y.

Great conversation! -

Treatid

54I’m wondering how far you’re willing to push the role of context in relation to the progress of knowledge. I’d like to we you push it to the limit. — Joshs

Treatid

54I’m wondering how far you’re willing to push the role of context in relation to the progress of knowledge. I’d like to we you push it to the limit. — Joshs

I feel there isn't (or shouldn't be) a choice. The significance of context is readily observed and widely acknowledged. It isn't a new insight.

Any rational viewpoint has to incorporate the role of context.

A half truth is (colloquially) a lie. Half accepting the significance of context is a denial of direct experience.

So - yes - to the limit.

socorro’s g he idea that knowledge — Joshs

More context please. I'm not sure what this is referencing.

What appears consistent or inconsistent, true false , harmonious or contradictory, is not the result of a conversation between subjects and a recalcitrant, independent reality, but a reciprocation in which the subjective and the objective poles are inextricably responsive to, and mutually dependent on each other. — Joshs

I'm somewhat allergic to the mere suggestion of 'objective' as I perceive it to be commonly bound to hidden/obscured impossible assumptions. But beyond that - yes, absolutely.

(I'm expanding the point - not arguing with you)

We are that which interacts. Interaction is a two way process. The act of observation changes us - and changes that which is observed.

Possible/impossible

We can describe our experiences with respect to our other experiences. We understand joy with comparison to misery (and contentment, ennui, pride, shame,...).

It is impossible to describe anything absent our experiences.

A connected universe directly impacts what knowledge is.

The mathematical attempt to create a universal language free of individual bias is a fundamental misunderstanding of the nature of existence.

It is an impossible task.

Knowledge and understanding aren't fixed points. They are a continuous active process. Your (everyone's) engagement with the universe is a critical part of the process.

Agreement

I agree with what you are saying but I want to keep pushing these to its ultimate conclusion.

Context has significant real world implications.

When we take context seriously we see that the explanation for large parts of mathematics isn't even wrong. The idea of understanding and significance separated from an individuals interactions is meaningless.

The effort invested in seeking objective truths (independent of context) is wasted.

So much agreement - but the devil is in the details

If you doubt that there is an objective context, how is it that almost all human beings of a particular intelligence are able to learn that 1+1 = 2? — Philosophim

- 1. The choice is not between objective and chaos. The choice is between objective and relative. They are both approaches to describing a universe with (perceived) structure.

General Relativity (GR) is wholly incompatible with Newtonian Mechanics (NM). Each observer in GR makes measurements that are inconsistent with other observers (according to the rules of NM). People who try to comprehend General Relativity using the assumptions of Newtonian Mechanics are in for a very bad time.

This does not make General Relativity chaotic. GR describes our universe, structure and all.

To the extent that you are implying that I think our experiences are chaotic with no common factors - I have failed to communicate on a monumental level. (I am challenging assumptions that are generally taken as a given. Without the context of agreed assumptions it can be difficult to interpret language).

- 2. 1+1=2 is true within Euclidean Geometry. We know for a fact that our universe is non-Euclidean. (c.f. General Relativity). A flat plane is a passable approximation for common human experience on the surface of the Earth.

Most people are raised in an environment where 1+1=2 is good enough but an astrophysicist is going to ask you the context before they agree.

Non-Euclidean spaces are all the possible spaces that aren't Euclidean (flat). There are infinitely many such spaces and they include curved, bent, and discontinuous systems.

As such, for all x there exists a non-Euclidean space such that 1+1=x.

Which is to say, there are infinitely many more systems in which 1+1 != 2 than in which 1+1=2.

Definitions

Likely its in our definition differences. — Philosophim

A statement is a piece of universe describing another piece of universe.

In a closed system (like the universe) all definitions are circular. That is A --> B --> A.

Which is to say that according to the common conception of 'definition' there are no definitions.

We can describe A in terms of B. We can describe B in terms of A. That's it. That is the complete list of things we can do with language.

Everything else is an aspect of this mechanism of language.

Language works. We describe A in terms of B and B in terms of A and we've built society.

In the entire history of mankind there has never been a non-circular definition.

Or, more constructively, meaning is dependent on context.

What I am doing is trying to break down complex concepts into more simple and easier to comprehend ideas. People think better when you can get down to fine grained foundations, and build on top of them. — Philosophim

Do they? You have evidence of this?

Context is critical because both we and our world are in continual motion. We have a system of constructs that are organized hierarchically into subordinate and superordinate aspects such that most new events are easily subsumed by our system without causing any crisis of inconsistency. When we embrace new events by effectively anticipating them, our system doesn’t remain unchanged but is subtly changed as a whole by the novel aspects of what it encounters. — Joshs

Joshs describes how experiences (such as new ideas) are more easily digested when they largely align with our expectations for those experiences.

In this conception (which I agree with), the ease of assimilation is how closely new ideas fit within our existing framework.

Here the measure of complexity of a new idea is determined by our existing framework. A simple idea is one that can be easily incorporated into existing conceptions with minimal effort.

Contrariwise, An idea that subverts existing expectations is generally difficult to digest even when the foundation is as simple as "context matters" or "all definitions in a closed system are circular". - 1. The choice is not between objective and chaos. The choice is between objective and relative. They are both approaches to describing a universe with (perceived) structure.

-

Philosophim

3.5kSo much agreement - but the devil is in the details — Treatid

Philosophim

3.5kSo much agreement - but the devil is in the details — Treatid

True! Even if there is disagreement, I enjoy reading your details.

1. The choice is not between objective and chaos. The choice is between objective and relative. — Treatid

I agree with this.

General Relativity (GR) is wholly incompatible with Newtonian Mechanics (NM). — Treatid

That's not quite correct. NM works at small bodies, but does not scale to large bodies. GR works with large bodies, and when you scale it down to small bodies, it results in NM. That may be irrelevant however, your point is really you seem to think I believe in chaos versus objective. If the example doesn't quite work, I still want to make sure I understand you point. If I don't quite understand it, please try again.

1+1=2 is true within Euclidean Geometry. We know for a fact that our universe is non-Euclidean. — Treatid

This is also not true. We have Euclidean and non-Euclidean applications depending on what we're measuring. Just like big vs small bodies, the context of how and what we're measuring matters for the equation.

Which is to say, there are infinitely many more systems in which 1+1 != 2 than in which 1+1=2. — Treatid

No. If the definition of 1, +, =, and 2 are the same, the result is the same. We can change the definitive context of each of those symbols, so 1 would would translate to 3, and 2 would translate to 8. In which case yes, 1+1 != 2 because that would translate to 3+3=8. Once you have solidified your concepts, the application can be inductive or deductive. Yes, we can change the meaning of the symbols to whatever we want. But once we decide on them, there is a set logic that always follows.

In a closed system (like the universe) all definitions are circular. That is A --> B --> A.

Which is to say that according to the common conception of 'definition' there are no definitions.

We can describe A in terms of B. We can describe B in terms of A. That's it. That is the complete list of things we can do with language. — Treatid

My theory escaped that circularity. You can start from the fact you discretely experience, and assign any of those discrete experiences as words in your memory. The base discrete experience is the foundation. It requires no further description. It is when we try to communicate these experiences with other people that we have to find common meaning somehow in symbols. Once common meaning can be established, then both of us can deductively conclude that 1+1=2 objectively.

In the entire history of mankind there has never been a non-circular definition.

Or, more constructively, meaning is dependent on context. — Treatid

Again, we both have discrete experiences. We are both able to assign that personal experience to a common symbol for common ground. We could not communicate at all if we did not do this. And yet we're able to. You can't quite provide your discrete experience to me, and I can't quite provide my discrete experience to you, but we can come to a common enough ground to communicate the essential picture of the experience without the specific picture of the experience itself.

What I am doing is trying to break down complex concepts into more simple and easier to comprehend ideas. People think better when you can get down to fine grained foundations, and build on top of them.

— Philosophim

Do they? You have evidence of this? — Treatid

I do. :) I was a high school math teacher for five years. This is one of the many techniques to teach something effectively to others. I currently program for a living and part of the best practices is to code in bite sized pieces for readability. I have an engineering friend that has shown me diagrams that break complex components into simple to digest pieces. There is a certain limit in how much information a human can hold at once in thoughts. We use 'grouping' to help this.

Try to memorize this number by single digits: 24777977

Now try to remember it by grouping it: 24-777-977 The second is much easier.

This is also what words are for. Grouping complex and detailed concepts into generalities. When I say "Physics" you don't think of the entirety of every physical law and formula. We break physics down into "theories" and "formulas". Too detailed, and you can't comprehend how it all fits together. Not enough detail and the generality seems obtuse and overly generalized.

Joshs describes how experiences (such as new ideas) are more easily digested when they largely align with our expectations for those experiences.

In this conception (which I agree with), the ease of assimilation is how closely new ideas fit within our existing framework. — Treatid

Agreed. This is because the human mind favors efficiency and 'good enough' over perfection. Sometimes that bites us down the road and I'm not immune to it. But what ensures the base of that framework in a rational sense versus an ideological sense? Rational frameworks can weather challenges that reality throws at it by adaptation. Ideological or emotional frameworks oftentimes have to go to great lengths to cover up its rational holes, because some framework is better than no framework at all.

That is why an idea can be unique and correct, but entirely rejected. One has to shape new discoveries in relation to the current framework so that there can be understanding. People will tentatively explore the new framework only if they see benefit. If those that adopt it start to see success, others will follow. -

Treatid

54Try to memorize this number by single digits: 24777977

Treatid

54Try to memorize this number by single digits: 24777977

Now try to remember it by grouping it: 24-777-977 The second is much easier. — Philosophim

Bitesize isn't quite the same as simple - or at least, not the idea of simple I had in mind.

Talking is a complex physical, biological and mental process. To the extent that the existence of the universe is a pre-requisite for talking, it is a complex process albeit one we engage in frequently.

As such - my point on this matter was that the perception of simplicity (i.e. starting from a minimal foundation) may be misguided. Specifically, we spend the first years of our lives learning to walk and talk and building a broad foundation of awareness of the basic mechanics of the universe.

I would argue that new knowledge is absorbed and integrated more rapidly the more of that foundation the new knowledge connects to. Ideal knowledge flow would involve wide kinaesthetic activation.

Problem Spaces

*discussion, not disagreement*

The more I interact with your ideas, the more familiar and relatable they become.

Generally, people don't immediately see the value in an argument. Rather, people integrate the components of an argument over time as they interact with it.

That is, a person starts in some initial state and incrementally approaches understanding.

A child doesn't understand arithmetic on first presentation but becomes incrementally more familiar with exposure.

This applies to Artificial Intelligence training too.

I'd argue that this incremental approach to solutions is a majority of human cognition.

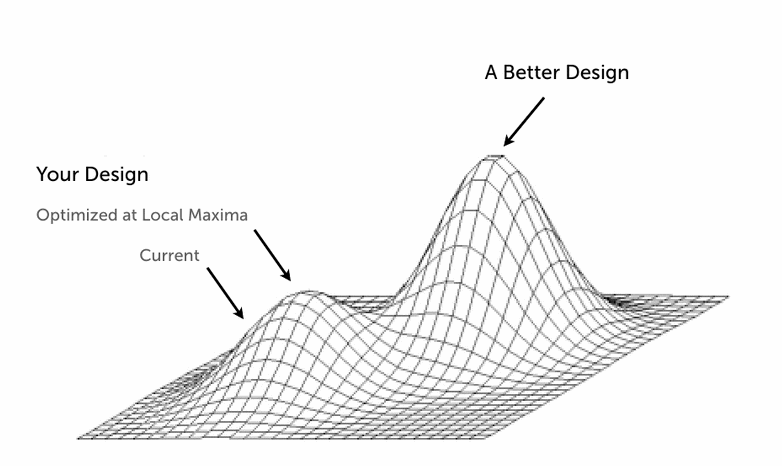

There is, however, a known pitfall with this mechanism: Local maxima...

Maxima

A hill climbing algorithm can get stuck at a local maxima and never find the global maxima.

This is a common problem with training AI where the best fit finds a local maxima solution but misses the global maxima. In complex problem spaces there is no clear mechanism for determining whether the current solution is a local or global maxima.

Knowledge and Induction

In light of the above, what is your understanding of the process of cognition? Are your thought processes strictly logical? strictly asymptotic (approaching a solution incrementally)? A mixture? something else?

If relevant - what would you expect two disputants with different local maxima to a given problem to do? -

Philosophim

3.5kThe more I interact with your ideas, the more familiar and relatable they become. — Treatid

Philosophim

3.5kThe more I interact with your ideas, the more familiar and relatable they become. — Treatid

That is a very nice compliment and I am humbled to see it. You have a keen and curious mind, and you've given me plenty to think on as well.

A hill climbing algorithm can get stuck at a local maxima and never find the global maxima. — Treatid

Yes. I've thought about this a long time ago but never had anyone bring this aspect up before. That is because we create perfectly logical systems. What a perfectly logical system lacks is induction, and a variety of approaches towards the same problem. Since I thought of this, machine learning has introduced 'induction' and imperfect data into systems, and we have largely escaped the issue you note.

Here's a fun video on machine learning.

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=Lu56xVlZ40M

But lets talk at the level of the theory as well. If you recall I labeled four classifications of induction, probability, possibility, plausibility, and irrational. As a quick reminder

Probability-Predicted outcomes based on know limitations. A coin has 50/50 chance of one side on flip.

Possibility- What has happened once is believed to be able to happen again.

Plausibility-A pure untested imagined scenario then is not immediately contradicted by what we know. Maybe aliens exist a billion light years away.

Irrational - A belief that what is applicably known is wrong. 1+1=2, but I believe its really 3.

While plausibility and irrational beliefs are looked down upon in established systems, they are invaluable in discovering new systems of thought.

Plausibility is fairly obvious, as its essentially imagination and hypothesis. But irrationality is also incredibly useful in some circumstances. To break out of local maximum, sometimes you have to do something against the grain that everyone thinks is impossible.

In the life of a human, I can think of at least one example where irrational beliefs are useful. There may be times when one can no longer come up with plausible explorations. But an irrational exploration is essentially poking at the already establish system. Its a stress test of sorts. It can find holes in logic no one realized. You can't have the majority of your population being irrational, but having a few is useful.

And this leads to the next part that you may find more interesting. How a society tackles induction.

In general we have one algorithm run a program, and alter it slightly. It evolves from its previous data, and seeks a solution to it. But after a point it eliminates other explorations. What if we had multiple ai's running separately and tweaked the amount of 'inductive' decisions they made?

For example

AI 1: 100% logical decisions

AI 2: 98% logical, 1% probable decisions, 1% possible decisions.

AI 3: 96% logical, 1% probable, 1% possible, 1% irrational decisions.

It would be interesting to see where each AI ended up. Especially if we duplicated this experiment millions of times with the same AIs, and even different variations.

I view humanity as a whole as the biological variant of this experiment. We have potentially millions of humans looking at a problem with different levels of emphasis on deduction vs induction. The difference is we have more of an emphasis on the induction part then the logical decisions. That's because human intelligence is optimized for efficiency, and pure logical and verified deductive thought takes the most time out of all approaches.

So where do I fall? The reality is that we have a propensity to favor inductions, and at the lower end of the hierarchy in a lot of our thinking. We are emotional beings with bias, and our nature is to rationalize what gives us what we want while tending to disregard that which does not.

https://www.universityofcalifornia.edu/news/when-it-comes-politics-youre-not-rational-you-think

“What we find is both sides are equally biased in their own direction,” Ditto said.

People are savvy at spotting bias in other people’s arguments, but they consistently fail to recognize bias in themselves."

As such, I try to use the hierarchy myself. I first favor strong facts and conclusions. Probabilities and possibilities are strong contenders. I try to avoid plausibilities as conclusions, only as possible avenues of exploration. And I constantly question if I'm wrong. Typically when I come up with an idea, I explore it, but then I try to disprove it myself. It wasn't easy at first, and it can still be tough when you have an idea you really like, but that habit is invaluable to cultivate. I work on not sinking into the trap of arrogance or hubris, and keep myself grounded that I am no better than any other human being. I try to listen to anyone no matter how new or inexperienced they might seem as insight can be found anywhere. As you noted, we all have a propensity for a local maximum, and it can be anyone who can break us out of it.

That being said, I'm still human. No matter how brilliant any human is, their intelligence was designed in the petri dish of evolution, not for optimal conclusive thinking. This is why I believe AI can be the next advancement of the human race. If we can get over our own biases, we can have something think inefficiently with massive amounts of electricity that can work at a logical level we can only dream of.

Anyway, a bit of my thoughts. Let me know what you think. -

Treatid

54

Treatid

54

Fun video!

I like what you are putting down. This seems very reasonable to me.

However, I find myself unclear as to your distinction between deduction and induction.

Pattern Matching

and pure logical and verified deductive thought takes the most time out of all approaches. — Philosophim

I see pattern matching.

Where you describe sheep and goat parts, I would generalise these as shapes or patterns. We see a pattern and then later compare our memory of the pattern with new experiences to determine how we interpret the new experience. - just as you describe.

Perceiving, storing and comparing patterns is the subject of your first post.

Your second post covers inductions which I take to be a refinement of the pattern matching where you examine how well patterns match and create a hierarchy from exact matches (probable) through general similarity (possible) and vague correspondence (plausible), to stark disjunction (irrational).

This all seem eminently sensible to me.

However, you also refer to deduction and logic as preceding induction.

I think your description of induction is sufficient to cover all human knowledge exploration. And yet you appear to imply the existence of another mechanism that you haven't addressed.

Could you go into more detail regarding the mechanisms of deduction? -

Philosophim

3.5kCould you go into more detail regarding the mechanisms of deduction? — Treatid

Philosophim

3.5kCould you go into more detail regarding the mechanisms of deduction? — Treatid

Certainly, there can be a lot of confusion around deduction vs induction as a context that often gets mistakenly applied to it is "truth". But deduction and induction have never meant to imply the truth of their conclusions. They imply the necessary logical outcome that results from a set of premises.

Before we get to matching memory, let me explain deduction and induction in their raw forms.

A conclusion has a set of what we call essential properties that define it. These are the properties that when fulfilled, we say, "This is 'that'". The number '2', is two one's grouped together. No other properties really matter. Whether the two things are candy, fruit, or cards, what is essential to the concept of '2', is the grouping of two ones.