-

jorndoe

4.2kThus spoke Kant, Russell, Frege or whomever they all were.

jorndoe

4.2kThus spoke Kant, Russell, Frege or whomever they all were.

But what do you think? Feel free to justify your stance (that's the intent of this post).

I'll vote Nope for the time being. Here follows a brief justification.

Formally, where φ is a predicate (without unrestricted comprehension), x is a (bound) variable, and S is a set, existential quantification is properly written as

- ∃x∈S [ φx ]

and this is a proposition, which may be true or false. In more ordinary language:

- there exists an x in S so that φ holds for x

- e.g., there exists (∃) a tree (x) in the forest (S), which is green (φ)

- or just, there is (∃) a round (φ) apple (x) in the bowl of apples (S)

If the φ symbol could be ∃, then you could already have x, except x does not exist, which seems wrong, since what was x in the first place then? If "exists" is a predicate which happens to be false for x, then it would seem that x is both present and absent. A fundamental demarcation among existing on paper, as it were, and also elsewhere, would have to be specified, but, more onerously, you'd have to contend with strange expressions, such as

- ¬∃x∈S [ ∃x ]

- ∃x∈S [ ¬∃x ]

- ∃x∈S [ ∃x ]

- ¬∃x∈S [ ¬∃x ]

which read as either nonsense or tautological.

Going by Quine, to exist is to be the value of a bound variable, which is x in the expression.

Thus, in general, existence is not a predicate, ∃ is not just another φ, though we may sometimes talk as if it were, and still make some sense.-

Is existence a predicate? Yep, existence is a fine predicate36%Nope, existence is not a predicate50%A little of this, a little of that, or something14%

-

TheMadFool

13.8kExistence is a property. One simple reason can be drawn from science. Entities are theorized, predicted and then sought for. Imagine a hypohetical particle x. We look for its existence. In that sense ''existence'' is a property and finding x we assign the property ''existence'' to x -

unenlightened

10kHow would you formalise the title?

unenlightened

10kHow would you formalise the title?

There does not exist a predicate (x) in language (S) which has the meaning, 'exists' (φ).

I don't know, but there is a slight aroma of cutting off the branch one is standing on here... is it a rule that denies its own expression? -

jorndoe

4.2k@TheMadFool, how to demarcate fictional and real entities?

jorndoe

4.2k@TheMadFool, how to demarcate fictional and real entities?

If you suppose that a fictional entity exists, then what would it take for it to be real?

It seems like fictional (not real) entities exist as their hypotheses (or definitions) alone.

@unenlightened, according to those pesky objectivists "existence exists", though I think Russell argued otherwise.

Does existence then not exist...? Maybe we should have a poll on that one as well.

How about this one? "There exists an apple in the bowl of apples, so that apple does not exist." :)

There are cases where "existence is a predicate" comes through as nonsense, which makes me think that (generally) "existence is not a predicate".

As far as I can tell, there isn't anything further that "to exist" can reduce to; existence is ground if you will.

Another angle:

We commonly characterize things by predication, quiddity — what those things are.

These are different propositions from merely existing though — that something exists.

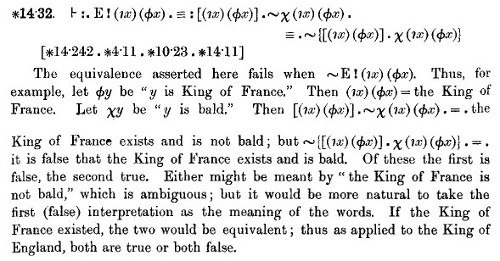

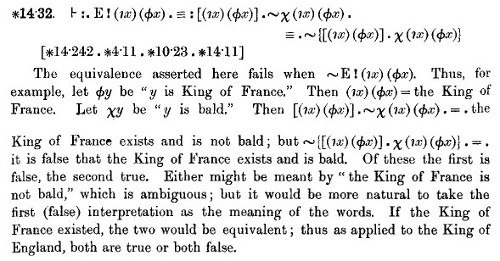

By the way, is the King of France bald or not?

Russell and Whitehead:

-

unenlightened

10kDid you answer my question, but I'm too stupid to understand it? Or was the question not clear enough? Can 'existence is not a predicate' be formalised without using existence as a predicate?

unenlightened

10kDid you answer my question, but I'm too stupid to understand it? Or was the question not clear enough? Can 'existence is not a predicate' be formalised without using existence as a predicate?

I'm not the big logician, but I know that existence is tricksy. It can be readily proved that there is no greatest prime number. One supposes that one exists, and then shows there is a bigger one. But then that feels different from the question of whether or not there exists hair on someone's head. I feel like we can put restrictions of this sort on language for certain purposes, but for other purposes I might define existence as that which is immune to argument. -

Agustino

11.2kI hope you don't get upset at me, but why should we care about answering this question? What is the ramification of it that makes it an interesting problem philosophically speaking, apart from appeals to authority (other philosophers have dealt with it), and the trivial reason that it just happens to be a question we dreamt up (cause I'm sure we don't pursue every question we dream up)?

Agustino

11.2kI hope you don't get upset at me, but why should we care about answering this question? What is the ramification of it that makes it an interesting problem philosophically speaking, apart from appeals to authority (other philosophers have dealt with it), and the trivial reason that it just happens to be a question we dreamt up (cause I'm sure we don't pursue every question we dream up)? -

Agustino

11.2k

Agustino

11.2k

In my opinion, concepts are concepts and the things they signify are the things they signify. For example, a circle can be taken purely as a concept. A circle as a concept is not round, it doesn't have a radius, etc. - it's just a concept. However, that which the concept of the circle signifies does have a radius, is round, and can exist or not exist. We get confused because we don't have two different words to distinguish between the circle, and the concept of the circle so we equivocate. It's one thing for a concept to exist, and it's another for that which it signifies to exist.Existence is a property. One simple reason can be drawn from science. Entities are theorized, predicted and then sought for. Imagine a hypohetical particle x. We look for its existence. In that sense ''existence'' is a property and finding x we assign the property ''existence'' to x — TheMadFool -

Wosret

3.4kExistence isn't a predicate, because to exist is to stand out, be distinct, but saying that something exists doesn't introduce a new distinction to the equation. Saying that something exists doesn't tell you anything new about it.

Wosret

3.4kExistence isn't a predicate, because to exist is to stand out, be distinct, but saying that something exists doesn't introduce a new distinction to the equation. Saying that something exists doesn't tell you anything new about it.

Saying that something doesn't exist is more like saying that it cannot be found, it doesn't strip it of any particular quality, and I don't consider this a proper use of language anyway. If something truly didn't exist, then there would be nothing to talk about not existing.

In thinking that existence is a predicate, we immediately wish to predicate anything said to exist or not exist, and this leads to confusion in my view. It exists, therefore it has the qualities of being material, or occupying space and time. Or it doesn't exist, this must mean that it is lacks those and such qualities -- but then can it really be said that we're in possession of a such a powerful predicate, so that we know that universal quality for existence, and know that it must be present in every single thing that exists in all realms and modes, and possible worlds? All scales and possibilities?

Predicating something with "existence" simply imports our metaphysical presuppositions in my view, rather than actually zones in the very quality that grants something existence. My view is both cool because something that truly doesn't exist isn't there at all in the first place to not exist, and resting on distinction it's far more phenomenological, which I take to be both more grounded in experience, and humble in its reach. -

Joseph

19Existence is a predicate because this statement makes complete sense:

Joseph

19Existence is a predicate because this statement makes complete sense:

∀x∈S[¬∃x]

The universal quantifier does not require existence. This statement says that for every member of S, it doesn't exist. Since there are no members of S, we can assign any attribute we want.

The only case where the above statement makes sense of course is when S is the empty set. If it had members, it would be false. And it works for the empty set because, again, the universal quantifier does not require existence. -

fishfry

3.4k∀x∈S[¬∃x] — Joseph

fishfry

3.4k∀x∈S[¬∃x] — Joseph

I do not believe the existential (or universal) quantifiers may stand alone. Rather there must be a unary predicate P so that you can write ∃xP(x).

If you have a reference illustrating a use of a standalone quantifier like ∃x I would appreciate a link or specific reference.

An expression such as ¬∃x is meaningless, as is ∀x∈S[¬∃x]. That's just not a well-formed formula in predicate logic.

If the general form of the existential quantifier is ∃xP(x) then in your example you are saying that ¬∃x may be a predicate. So you are assuming the thing you are trying to prove. In fact ¬∃x is not a predicate. -

Joseph

19

Joseph

19

How about if you wanted to state that a set contains at least one member? The only sensible way to write it is ∃x∈S. That is a case of a standalone quantifier. That isn't to say anything about it being a predicate, but it could be extended for that case.

Next, how would you state that a set is empty in predicate logic? -

Cavacava

2.4kThe principal of sufficient reason requires reasons why the laws that govern the universe are as they are and are not otherwise and even if such a reason is found it must account for this reason ad infinitum...to "a reason not conditioned by any other reason, and only the ontological argument is capable of uncovering". (Quentin Meillassoux AF pg.33).

At least one absolute being is absolutely necessity for the laws, of universe to be necessary if not, everything could be otherwise. Kant's refutation of the ontological argument ended dogmatic metaphysics. -

fishfry

3.4kHow about if you wanted to state that a set contains at least one member? — Joseph

fishfry

3.4kHow about if you wanted to state that a set contains at least one member? — Joseph

∃x∈S (x ∈ S)

That would be the formal way, since x ∈ S is a predicate.

The only sensible way to write it is ∃x∈S. — Joseph

Technically that is a convenient abuse of notation. Everyone writes it that way, everyone knows what it means. But it's not actually correct if one is being precise.

That is a case of a standalone quantifier. — Joseph

No. Besides, it has a completely different form than your earlier example of writing ∃x without any predicate at all. You are giving two completely different examples. ∃x by itself is is meaningless. ∃x∈S is technically wrong but everyone understands that it's a shorthand for ∃x(x∈S).

Next, how would you state that a set is empty in predicate logic? — Joseph

¬∃x(x∈S). -

Srap Tasmaner

5.2k

Srap Tasmaner

5.2k

Hmmm. To me science makes more sense the other way around, where you have some idea what your domain is -- and you might get that wrong and have to change it -- and the question is either "What in my domain has the properties my effect needs it to?" or "Does anything in my domain have such-and-such a property?"

The formalism was developed for mathematics, where you always specify the domain. Science has no choice but to follow suit. What are you going to do? look everywhere? at everything? -

Srap Tasmaner

5.2kThere does not exist a predicate (x) in language (S) which has the meaning, 'exists' (φ). — unenlightened

Srap Tasmaner

5.2kThere does not exist a predicate (x) in language (S) which has the meaning, 'exists' (φ). — unenlightened

I think that may be the wrong approach. It's a little like saying, "There does not exist a predicate (x) in language (S) which has the meaning, 'and' (φ)."

Existence is not a predicate because it is something else, namely a quantifier. It's just a matter of getting it in the right logical bucket. -

Michael

16.8kWell, what does it mean to exist? If, for example, to exist is to have a location in space, and if having a location in space is a predicate then existence is a predicate. Or for something abstract like numbers, we might say that to exist is to have a use in some system of mathematics, and if having a use in some system of mathematics is a predicate then existence is a predicate.

Michael

16.8kWell, what does it mean to exist? If, for example, to exist is to have a location in space, and if having a location in space is a predicate then existence is a predicate. Or for something abstract like numbers, we might say that to exist is to have a use in some system of mathematics, and if having a use in some system of mathematics is a predicate then existence is a predicate. -

Michael

16.8kTo exist, logically speaking, is generally just to be the subject of a predicate. — jamalrob

Michael

16.8kTo exist, logically speaking, is generally just to be the subject of a predicate. — jamalrob

But "is a fiction" is a predicate, yet fictional things don't exist.

I wonder if perhaps there's conflation between the existential quantifier in logic and "existence" as an ordinary language term. -

jorndoe

4.2kApologies @unenlightened, skim-reading is poor reading, my bad. The two propositions, "existence is not a predicate" and ∃x∈S [ φx ], are sufficiently different that I couldn't formulate the former as an example of the latter.

jorndoe

4.2kApologies @unenlightened, skim-reading is poor reading, my bad. The two propositions, "existence is not a predicate" and ∃x∈S [ φx ], are sufficiently different that I couldn't formulate the former as an example of the latter.

- ∃ ∉ Φ, where Φ is all φs (no unrestricted comprehension please)

Philosophy and forums? In my own case, also looking for (in)consistencies among different things, e.g. ∃ and quiddity (old post).why should we care about answering this question? — Agustino

In this case, any such meanings (including hypothetical) already exemplifies existence. Seems in some ways, existence is auto-presupposed.Well, what does it mean to exist? — Michael

Anyway, using existence as a predicate can sometimes lead to nonsense, and other times make sense. So, ∃ is not just another φ, except sometimes it is? -

unenlightened

10kIs "to be a predicate" a predicate? I suppose so, but haven't figured out whether that's problematic. — jorndoe

unenlightened

10kIs "to be a predicate" a predicate? I suppose so, but haven't figured out whether that's problematic. — jorndoe

I haven't figured it out either, but if it's problematic, it's logic that has a problem, not existence. If existence declares that particles are waves or whatever quantum weirdness you care to mention, logic will just have get it's act together about it. It might just be the usual problem of ordinary language being its own meta-language.

But "is a fiction" is a predicate, yet fictional things don't exist. — Michael

Fictional things don't exist, but fictions do. -

Metaphysician Undercover

14.8kTo exist, logically speaking, is generally just to be the subject of a predicate. — jamalrob

Metaphysician Undercover

14.8kTo exist, logically speaking, is generally just to be the subject of a predicate. — jamalrob

This is where the problem is then. If, from the perspective of what is logical, to exist is simply to be the subject of a predicate, then logic isn't consistent with what we normal mean when we say "exists". This is why logic and epistemology must be based in a good ontology, not vise versa. If we turn this around, and try to base an ontology in what logic makes of existence, we are headed into problems. -

Owen

24Of course 'exists' is a predicate.

Owen

24Of course 'exists' is a predicate.

'a exists', has 'a' as its subject and 'exists' as its predicate.

But, exists is not a primary predicate.

(Ga & (a exists)) <-> Ga, ie. (a exists) does not add information to Ga.

If we define (a exists) as ∃F(Fa), and

(G exists) as ∃xGx.

1. |-. Ga -> ∃F(Fa). |-. Ga -> (a exists).

2. |-. Ga -> ∃x(Gx). |-. Ga -> (G exists).

3. |-. Ga -> ∃F∃x(Fx). |-. Ga -> ((Ga) exists).

(x exists) <-> ∃F(Fx).

(x exists) <-> ∃y(x=y).

(x exists) <-> x=x.

(x exists) <-> ((~F)x <-> ~(Fx)). -

Srap Tasmaner

5.2k

Srap Tasmaner

5.2k

For "Ga" to be a wff, doesn't a have to be an object in your domain of discourse?

What sense can be made of asserting "Ga" if you don't already know that a exists? -

Agustino

11.2k

Agustino

11.2k

The whole conundrum seems a bit nonsensical to me. Nothing can be "proven" to exist. You can't even "prove" other minds exist. Classical theism does not claim to "prove" God in the sense of showing that it is irrational and illogical not to believe in God. Rather classical theism tries to give a defence of the faith which means to give very compelling reasons for believing in God, not a deductive and bullet proof argument. The premises of Aquinas' arguments can be denied for example. They are certainly sensible propositions that many people would be inclined to acknowledge, but one can still do the mental gymnastics required to deny them.For one thing, classical theism is in jeopardy. To claim that God can be proven or believed to exist, despite not knowing his essence, becomes a nonsensical distinction if existence isn't a predicate. — Thorongil -

Agustino

11.2k

Agustino

11.2k

That's nothing but an argument from authority. I asked you to use your head and give me an actual reason. Philosophers of the past may have thought it is important to debate whether existence is a property or not (because they were interested in the ontological argument) but maybe they were bothering to address unimportant and sterile matters to begin with (and later philosophers like Russell merely picked up on such sterility without questioning it). Maybe they were asking the wrong questions, and discussing dead ends. So just because philosophers have thought it important to discuss it, doesn't mean it really is important. So again, why is it important? Why should I care about resolving this issue? How will it change anything?Philosophy and forums? — jorndoe -

Thorongil

3.2kI'm not seeing a difference between "proving God to exist" and "giving very compelling reasons for believing in God." The latter statement just reads as a more wordy restatement of the former. The question of whether the proof is inductive or deductive seems irrelevant. A proof is a proof.

Thorongil

3.2kI'm not seeing a difference between "proving God to exist" and "giving very compelling reasons for believing in God." The latter statement just reads as a more wordy restatement of the former. The question of whether the proof is inductive or deductive seems irrelevant. A proof is a proof.

Welcome to The Philosophy Forum!

Get involved in philosophical discussions about knowledge, truth, language, consciousness, science, politics, religion, logic and mathematics, art, history, and lots more. No ads, no clutter, and very little agreement — just fascinating conversations.

Categories

- Guest category

- Phil. Writing Challenge - June 2025

- The Lounge

- General Philosophy

- Metaphysics & Epistemology

- Philosophy of Mind

- Ethics

- Political Philosophy

- Philosophy of Art

- Logic & Philosophy of Mathematics

- Philosophy of Religion

- Philosophy of Science

- Philosophy of Language

- Interesting Stuff

- Politics and Current Affairs

- Humanities and Social Sciences

- Science and Technology

- Non-English Discussion

- German Discussion

- Spanish Discussion

- Learning Centre

- Resources

- Books and Papers

- Reading groups

- Questions

- Guest Speakers

- David Pearce

- Massimo Pigliucci

- Debates

- Debate Proposals

- Debate Discussion

- Feedback

- Article submissions

- About TPF

- Help

More Discussions

- Other sites we like

- Social media

- Terms of Service

- Sign In

- Created with PlushForums

- © 2026 The Philosophy Forum