-

AmadeusD

4.2kYes, these are expressions of thought - they form a crucial part of it - that part that connects to the quite obscure aspect of non-linguistic thought with linguistic thought, but it is the linguistic aspect that gets discussed virtually everywhere — Manuel

AmadeusD

4.2kYes, these are expressions of thought - they form a crucial part of it - that part that connects to the quite obscure aspect of non-linguistic thought with linguistic thought, but it is the linguistic aspect that gets discussed virtually everywhere — Manuel

Yeah good, Nice.

I agree that this is what happens, outside minds. But, as noted earlier, this is simply an insufficient argument. On some accounts, less than half of people even experience linguistic thought. This is actually, specifically, and clearly, a support for my position: These people can speak about their thoughts despite having no corresponding mental language (ie, their mentation is not linguistic - not 'there is no mental language per se' - it could be a language of feeling, or otherwise (as discussed by another poster earlier)).

The linguistic expression of thought is direct, it comes from my brain and I articulate to you that aspect of thought which is capable of expression. — Manuel

It doesn't come from your brain. It comes from your linguistic faculties (larynx, tongue etc..) as a symbolic representation. Again, if you call that Direct, that's a side-step of convention. Fine. Doesn't really address the issue here, though. It's 'as good as', but it isn't.

We don't know enough about unconscious brain processes to say if non-linguistic thought is, or is not, language like. — Manuel

I disagree. We have (arguably, more than half) of people describing non-linguistic thoughts. We're good. And we know the results. It doesn't differ from expressing linguistic thoughts in any obvious way until the speaker is interrogated.

I have used thought in saying that it has likely has a non-linguistic basis, but this amounts to saying very little about it. — Manuel

I would say that's true. I'm unsure this says anything about either our positions. Thought may be, at-based, non-linguistic but clearly some significant number of people think in language, and some don't, as contrasted against each other. Either by convention, or logical necessity, they can't be the same thing.

You really enjoy pushing the idea of discomfort. — Manuel

Because it is, to me, clearly the reason for your position. You ahven't addressed this, and so I'll continue to push it until such time as an adequate response has been made. This isn't 'at you'. This is the position I hold. It seems coherent, and I've not yet had anyone even deny it. Just say other stuff.

I've said several times Kant's point — Manuel

And if Kant was wrong? As many, many people think?

we directly perceive objects — Manuel

In the language you are using, I have to accept this because this does not suppose any kind of phenomenal experience and so doesn't adequately describe all of what matters.

But If what you're saying is the eyes directly receive the light, I accept that.

You'll notice that nothing in this is the object, or the experience, or the subject. So we're still indirectly apprehending. Hehe.

Indirect would be something like attempting to find out a persons brain state if they are paralyzed — Manuel

No idea what you're talking about here so I wont comment. There are several unnecessary aspects to this.

They will tell you they are directly identifying an object by its colors, even if colors are no mind-independent properties. — Manuel

Convention rears it's head again. You're also describing a process of allocation. That isn't apt for the distinction we're talking about. I could definitely tell a biologist they are not directly perceiving the distal object of a phloem. What their response is has nothing to do with our discussion. Your point is taken, but it speaks to conventions. -

Manuel

4.4kThese people can speak about their thoughts despite having no corresponding mental language (ie, their mentation is not linguistic - not 'there is no mental language per se' - it could be a language of feeling, or otherwise (as discussed by another poster earlier)). — AmadeusD

Manuel

4.4kThese people can speak about their thoughts despite having no corresponding mental language (ie, their mentation is not linguistic - not 'there is no mental language per se' - it could be a language of feeling, or otherwise (as discussed by another poster earlier)). — AmadeusD

And in speaking about such non-linguistic thoughts, only the linguistic portions get communicated. If someone could attempt to describe in some manner, non-linguistic thought, it would be interesting to see. But the issue here is, are we discussing thought (whatever thinking is) or something else? Until we have a better notion of linguistic thought, we are going to remain stuck.

It doesn't come from your brain. It comes from your linguistic faculties (larynx, tongue etc..) as a symbolic representation. Again, if you call that Direct, that's a side-step of convention. Fine. Doesn't really address the issue here, though. It's 'as good as', but it isn't — AmadeusD

Come on man. People can use sign language, or sight, as was the case with Hawking, to express thought. But it does come from the brain, not from the tongue or the eyes...

I disagree. We have (arguably, more than half) of people describing non-linguistic thoughts. We're good. And we know the results. It doesn't differ from expressing linguistic thoughts in any obvious way until the speaker is interrogated. — AmadeusD

Describing non-linguistic thoughts how?

Because it is, to me, clearly the reason for your position. You ahven't addressed this, and so I'll continue to push it until such time as an adequate response has been made. This isn't 'at you'. This is the position I hold. It seems coherent, and I've not yet had anyone even deny it. Just say other stuff. — AmadeusD

If you want to call it convention, call it convention. I don't have a problem with direct and mediated. You take mediation to mean indirect.

I will once again say, we only have the human way of seeing things, not a "view from nowhere", which is where I assume you would believe directness could be attained.

I believe it makes more sense to argue that we directly see objects (mediated by our mind and organs) than to say we indirectly see an object, because it is mediated. "We indirectly see an apple." is just a strange thing to say, because the left-over assumption is that there is such a thing as directly seeing an apple, but on the indirect view, this is impossible, heck, there would be no apple nor object to say that remains when we stop interacting with it.

This left over aspect does not make sense to me. I think it is false.

Nevertheless, so that we may not continue this to infinity, I will readily grant that I am using a particular convention, because I think it makes more sense.

More important to me than direct/indirect is mediation, which I assume you would say is what indirectness is about. Fine.

And if Kant was wrong? As many, many people think? — AmadeusD

I think one can have issues with things in themselves (noumenon in a positive sense) for instance or may think that his specific a-priori postulates are wrong or disagree with his morality, sure, but to think his entire framework is wrong, well I think this is simply to dismiss what contemporary brain sciences say, not to mention common sense.

In the language you are using, I have to accept this because this does not suppose any kind of phenomenal experience and so doesn't adequately describe all of what matters.

But If what you're saying is the eyes directly receive the light, I accept that.

You'll notice that nothing in this is the object, or the experience, or the subject. So we're still indirectly apprehending. Hehe. — AmadeusD

Sure - we have an issue here too, what is an object? It's not trivial. Is it the thing we think we see, is it the cause of what we think we see or is it a mere mental construction only? Tough to say.

Convention rears it's head again. You're also describing a process of allocation. That isn't apt for the distinction we're talking about. I could definitely tell a biologist they are not directly perceiving the distal object of a phloem. What their response is has nothing to do with our discussion. Your point is taken, but it speaks to conventions. — AmadeusD

I will grant this as stated. I actually don't think that we disagree all that much on substantial matter, more so the way words are used. And I admit I am using direct in a manner that goes beyond the usual framing as "naive realism", which if anyone believes in that, they shouldn't be in philosophy or science, or I would wonder why they would bother with this. -

Pierre-Normand

2.9kWe are in an empty black room, looking at a wall. Two circles appear on the wall. One of the circles is going to grow in size and the other circle is going to move towards us (e.g. the wall panel moves towards us). The rate at which one grows and the rate at which the other moves towards us is such that from our perspective the top and bottom of the circles are always parallel.

Pierre-Normand

2.9kWe are in an empty black room, looking at a wall. Two circles appear on the wall. One of the circles is going to grow in size and the other circle is going to move towards us (e.g. the wall panel moves towards us). The rate at which one grows and the rate at which the other moves towards us is such that from our perspective the top and bottom of the circles are always parallel.

Two different external behaviours are causing the same visual phenomenon (a growing circle). It's impossible to visually distinguish which distal object is growing and which is moving towards us. — Michael

This is a great example. I agree that in such circumstances both external behaviors of the circles are likely to generate the same phenomenological experiences, side by side in your visual field, as it were. Yet, similarly to what might happen with a pair of Necker cubes, say (where each one of them affords two complementary interpretations), the observer could either (seem to) see both circles to be approaching or (seem to) see both circles to be growing in size. It is this phenomenological contrast that you appear to be overlooking. Those two possible phenomenological contents are structurally incompatible (involving a gestalt switch), are directly expressible in language, and are introspectively distinguishable. On those three separate grounds, I would maintain that (1) seeming to see a growing disk and (2) seeming to see an approaching disk are two distinct (and therefore immediately subjectively distinguishable) phenomenological states. This suggests that there is more to the visual phenomenon than just the raw retinal data. There is a sub-personal interpretive or organizational component that structures the experience in one way or another before it is given to conscious experience.

The case of the artist holding a ruler at arm's length in order to assist them in the construction of a sketch is also a telling example. The artist could also place a transparent glass sheet at an arm's length distance, close one eye, and trace the contours of the visible scenery on the sheet. By employing either the glass sheet or ruler method, the artist is essentially utilizing an "analogue computer" to calculate, relying on principles of projective geometry, how to generate a 2D mapping of the light patterns reaching their retinas from the 3D scene. This enables them to construct a flat picture that mimics the appearance of that scene, albeit with certain depth cues removed or discounted. But why would the artist need to do those analogue calculations, with the help of an external crutch, if the shapes and dimensions of their own retinal projections were already part of their phenomenology? Medieval artists who hadn't yet thematised the principles of perspective, or yet invented such techniques as the pencil (held at arm's length) method, had a tendency to draw people scattered across a landscape exactly as they immediately looked like to them to be: as remaining the same sizes irrespective of their distances from the observer.

Your own conception of the direct phenomenological objects of visual experience makes them, rather puzzlingly, invisible to the observers and only indirectly inferrable by them on the basis of externally assisted analogue computations or deducible from the laws of perspective. -

creativesoul

12.2kDo you believe that naive/direct realism cannot deny color as a property of objects? I mean, I suppose I do not see any reason that a position like naive realism cannot correct any flaws based upon newly acquired knowledge such as color perception. — creativesoul

I think that if they admit that colours are not properties of objects then they must admit that colours are the exact mental intermediary (e.g. sense-data or qualia or whatever) that indirect realists claim exist and are seen. And the same for smells and tastes. — Michael

I think that you've given indirect realism too much credit. I see no reason to think that if colors are not inherent properties of distal objects that the only other alternative explanation is the indirect realist one. They can both be wrong about color.

Olfactory and gustatory biological machinery work differently than vision. Light is not part of the objects we see. It helps facilitate seeing. Light does not help facilitate tasting and smelling.

Direct realists claimed that there is no epistemological problem of perception because distal objects are actual constituents of experience. Indirect realists claimed that there is an epistemological problem of perception because distal objects are not actual constituents of experience (and that the actual constituents of experience are something like sense-data or qualia or whatever).

Why can't distal objects be constituents of experience, and color not be an inherent property thereof? -

Pierre-Normand

2.9kI don't think there's necessarily anything narrow about the reductionism of a functionalist. A functionalist just doesn't separate functional consciousness from phenomenal. She views the two as necessarily bound together, so that explaining one explains the other. — frank

Pierre-Normand

2.9kI don't think there's necessarily anything narrow about the reductionism of a functionalist. A functionalist just doesn't separate functional consciousness from phenomenal. She views the two as necessarily bound together, so that explaining one explains the other. — frank

Sorry, I wasn't using the term "narrow" pejoratively as a in "narrow minded" but rather as in "narrow supervenience" as this concept is usually understood in the philosophy of mind. Functionalists typically have identified mental states with functional features of human brains: how they map motor outputs to sensory inputs.

The mental states therefore are deemed to narrowly supervene on brain states and functions. A functionalist might grant that the intentional purport of mental states (what makes beliefs about the world true or false, and what determines the identity of the objects perceived or thought about by the subject) supervene widely on the brain+body+environment, but they would still insist that the phenomenal content of perceptual states (how things look to people, subjectively) supervenes narrowly on internal representations realized in the brain. This would follow from them identifying those phenomenal contents with functional roles within the brain (i.e. how those states contribute to determine the input/output mappings) but such states would remain narrow in the intended sense.

Maybe I'm wrong about that though, since I don't know many functionalists besides Hilary Putnam who recanted this view rather early in his career to become a more full blown externalist about mental content. But if you know someone who endorses the "functionalist" label and who views phenomenal states to supervene widely on the brain+body+environment dynamics (like I do), I'd be happy to look at their views and compare them with mine.

What you're saying here is already true of functional consciousness. Every part of your body is engaged with the whole. The flowchart for how it all works together to keep you alive is startlingly large and complex, and along the endocrine system, the nervous system is the bodily government. However, none of this necessarily involves phenomenal consciousness. This is where you become sort of functionalist: that you assume that phenomenality has a necessary role in the functioning of the organism (or did I misread you?). That's something you'd have to argue for, ideally with scientific evidence. As of now, each side of the debate is focusing on information that seems to support their view, but neither has an argument with much weight. We don't know where phenomenal consciousness is coming from, whether it's the brain, the body, or quantum physics. We just don't know.

The reason why none of the sub-personal flowchart entails phenomenal consciousness may be mainly because it focuses on the wrong level of description. Most of the examples that I've put forward to illustrate the direct realist thesis appealed directly to the relationships between the subjects (visible and manifest) embodied activity in the world and the objective features disclosed to them through skilfully engaging with those features. I was largely agnostic regarding the exact working of the sub-personal flowchart (or neurophysiological underpinnings) that merely enable such forms of skillful sensorimotor engagements with the world. But I never was ascribing the phenomenal states to those underlying processes but rather to the whole human being or animal. -

Pierre-Normand

2.9kThe issue of the metaphysics of colors (and other secondary qualities) has come up in this thread, but the concept of color constancy has not been discussed much, unless I missed it. A few years ago I had discussed with my friends the phenomenon of shadows on snow or clouds appearing grey in real life but bluish on photographs. I asked Claude 3 Sonnet if it could figure out why that is the case.

Pierre-Normand

2.9kThe issue of the metaphysics of colors (and other secondary qualities) has come up in this thread, but the concept of color constancy has not been discussed much, unless I missed it. A few years ago I had discussed with my friends the phenomenon of shadows on snow or clouds appearing grey in real life but bluish on photographs. I asked Claude 3 Sonnet if it could figure out why that is the case. -

Pierre-Normand

2.9kRegarding the issue of the metaphysics of colors and the visual principle of color constancy, consider this variation on the checker shadow illusion originally conceived by Edward H. Adelson.

Pierre-Normand

2.9kRegarding the issue of the metaphysics of colors and the visual principle of color constancy, consider this variation on the checker shadow illusion originally conceived by Edward H. Adelson.

Is the color of the central square on the top surface of the cube the same as the color of the central square on the shadowed surface facing us? The former appears dark brown whereas the latter appears bright orange. The quality and intensity of the light being emitted by your computer monitor at the locations of those two squares (i.e. their RGB components) is exactly the same. But we don't perceive that. Our visual system compensates for the cues regarding the apparent ambient illumination and makes those squares appear to be different colors (which they would be if such a cube was seen in real life, in which case there would be no illusion!)

So, what is the content of our phenomenology regarding the colors of those two squares? Indirect realists might say that the two squares are "sensed" to have the same color (since their retinal projections excite the cones and rods in the exact same way) and the illusion that they have different colors is an inference that our visual system makes on the basis of such raw sense data. A direct realists would rather claim that what we seem to see - namely that the top square is brown and the facing square is orange) - is informed by the already processed and corrected information gathered by our visual system on the basis of the provided illumination cues.

Another challenge for the indirect realist would be to say what is the common color called that both those squares appear to exemplify if, according to them, they "look" the same. Do they both look orange? Do they both look brown? Something else that can't be expressed in words? -

Michael

16.8kWhy can't distal objects be constituents of experience — creativesoul

Michael

16.8kWhy can't distal objects be constituents of experience — creativesoul

Because experience does not extend beyond the body – it’s the body’s physiological response to stimulation (usually; dreams are an exception) – whereas distal objects exist outside the body.

If physical reductionism is true then experience is reducible to something like brain states. What would it mean for distal objects to be constituents of brain states?

If property dualism is true then experience is something like a mental phenomenon that supervenes on brain states. What would it mean for distal objects to be constituents of mental phenomena that supervene on brain states?

For distal objects to be constituents of experience it would require that experience literally extends beyond the body to encompass distal objects. I accept that this is how things seem to be, and it's certainly how I ordinarily take things to be in everyday life, but this naïve view is at odds with our scientific understanding of the world.

Direct realism would seem to require a rejection of scientific realism, and presumably an acceptance of either substance dualism or objective idealism.

I think that you've given indirect realism too much credit. I see no reason to think that if colors are not inherent properties of distal objects that the only other alternative explanation is the indirect realist one. They can both be wrong about color. — creativesoul

If colour is experienced but not a property of distal objects then it must be a property of the experience itself. I don't see how there can be a third option. -

Michael

16.8kThis suggests that there is more to the visual phenomenon than just the raw retinal data. There is a sub-personal interpretive or organizational component that structures the experience in one way or another before it is given to conscious experience. — Pierre-Normand

Michael

16.8kThis suggests that there is more to the visual phenomenon than just the raw retinal data. There is a sub-personal interpretive or organizational component that structures the experience in one way or another before it is given to conscious experience. — Pierre-Normand

I agree. But it is still the case that all this is happening in our heads. Everything about experience is reducible to the mental/neurological. The colours and sizes and orientations in visual experience; the smells in olfactory experience; the tastes in gustatory experience: none are properties of the distal objects themselves, which exist outside the experience. That, to me, entails the epistemological problem of perception, and so is indirect realism. -

Pierre-Normand

2.9kI agree. But it is still the case that all this is happening in our heads. Everything about experience is reducible to the mental/neurological. The colours and sizes and orientations in visual experience; the smells in olfactory experience; the tastes in gustatory experience: none are properties of the distal objects themselves, which exist outside the experience. They are nothing more than a physiological response to stimulation. That, to me, entails the epistemological problem of perception, and so is indirect realism. — Michael

Pierre-Normand

2.9kI agree. But it is still the case that all this is happening in our heads. Everything about experience is reducible to the mental/neurological. The colours and sizes and orientations in visual experience; the smells in olfactory experience; the tastes in gustatory experience: none are properties of the distal objects themselves, which exist outside the experience. They are nothing more than a physiological response to stimulation. That, to me, entails the epistemological problem of perception, and so is indirect realism. — Michael

While it's true that the environmental feedback we receive during our active explorations of the world must ultimately impact our brains via our bodies and sensory organs, it would be a mistake to conclude that all visual processing takes place solely within the brain. Although the brain plays a crucial role in coordinating perceptual activity, this activity also fundamentally involves the active participation of the body and the environment. Perception is not a passive, internal representation of external stimuli, but an interactive process that unfolds over time and space.

Imagine a person walking through a forest. As they move, the patterns of occlusion and disocclusion of the trees and branches relative to one another provide rich information about their relative distances and 3D arrangement. This information is not contained in any single neural representation, but rather emerges over time through the active exploration of the scene.

Relatedly, the case of extracting depth information through head movements for those lacking binocular disparity (due to strabismus or partial blindness, say) is a telling example. Even in the absence of the typical cues from binocular vision, the brain can integrate information over time from the changing optic array as the head/body moves to recover the 3D structure of the scene. This shows that the vehicle for visual perception extends beyond the brain alone to encompass the moving body as it samples the environment.

Consider also the case of haptic perception. When we explore an object with our hands, the resulting tactile sensations are not mere passive inputs, but are actively shaped by our exploratory movements. The way we move our fingers over a surface - the pressure, speed, and direction of our movements - all contribute to the resulting phenomenology of texture, shape and solidity.

Consider the act of reading Braille. The experience of the raised dots is not simply determined by the patterns of stimulation on the fingertips, but crucially depends on the reader's skilled movements and their expectations and understanding of the Braille system. The perceptual content here is inseparable from the embodied know-how of the reader.

Consider also the phenomenology of the tennis player, I think it also illustrates the interdependence of perception and action. The player's experience of the ball's trajectory and the court's layout is not a static inner representation, but a dynamic, action-oriented grasp of the unfolding situation. The player's movements, their adjustments of position, their swings, their anticipatory reactions, are not separable from their perceptual experience, but are constitutively part of their perceptual skills.

These examples all point to the same underlying principle that perceptual experience is not a passive, internal representation of external stimuli, but an active, embodied engagement with the world. The content and character of that experience is shaped at every level by the dynamic interplay of brain, body, and environment.

To insist that this experience supervenes solely on brain states is to miss the fundamental way in which perception is a skill of the whole organism, a way of being in and engaging with the world. The body and the environment are not mere external triggers for internal states, but are constitutive parts of the perceptual system itself.

(Thanks to Claude 3 Opus for suggesting the haptic perception and Braille examples!) -

Michael

16.8kAll this seems to be saying is that our body is continually responding to new stimulation, reshaping the neural connections in the brain and moving accordingly. That, alone, says nothing about either direct and indirect realism.

Michael

16.8kAll this seems to be saying is that our body is continually responding to new stimulation, reshaping the neural connections in the brain and moving accordingly. That, alone, says nothing about either direct and indirect realism.

Direct and indirect realism as I understand them have always been concerned with the epistemological problem of perception.

The indirect realist doesn’t claim that we don’t successfully engage with the world. The indirect realist accepts that we can play tennis, read braille, and explore a forest. The indirect realist only claims that the shapes and colours and smells and tastes in experience are mental phenomena, not properties of distal objects, and so the shapes and colours and smells and tastes in experience do not provide us with direct information about the mind-independent nature of the external world. -

frank

18.9kBut if you know someone who endorses the "functionalist" label and who views phenomenal states to supervene widely on the brain+body+environment dynamics (like I do), I'd be happy to look at their views and compare them with mine. — Pierre-Normand

frank

18.9kBut if you know someone who endorses the "functionalist" label and who views phenomenal states to supervene widely on the brain+body+environment dynamics (like I do), I'd be happy to look at their views and compare them with mine. — Pierre-Normand

I did say you were "quasi-functionalist." I think if science were to show that functional consciousness is indeed a holistic relation between body and world, a functionalist would quickly adapt to that view and insist that talk of consciousness be limited to that relation. Isn't that your view?

Most of the examples that I've put forward to illustrate the direct realist thesis appealed directly to the relationships between the subjects (visible and manifest) embodied activity in the world and the objective features disclosed to them through skilfully engaging with those features — Pierre-Normand

Right. I don't think phenomenal consciousness is involved in navigation of the world as you seem to think it is. Walking, for instance involves an orchestral display of muscle movement which wouldn't happen at all if phenomenality had to enter the process. Consciousness of sights and sounds is a time consuming activity. I'm not saying you couldn't become aware of some of what your body is doing as you interact with the world. Phenomenal consciousness is like a flashlight. You can even direct it to the sensory input that handles proprioception, but your body certainly doesn't wait for you to do that before it orients itself in space. -

Luke

2.7k"Correct", "Veridical", or not, is the wrong framing. — hypericin

Luke

2.7k"Correct", "Veridical", or not, is the wrong framing. — hypericin

And yet you argue that we can never know if the smell of smoke indicates that there is smoke (or that one perceives smoke), due to the possibility of illusion, hallucination or error.

Naive realism and indirect realism are both based on the presupposition that there is a “correct” way to perceive the world, which is to perceive the world as it is in itself. Naive realism supposes that we do perceive the world as it is in itself. Indirect realists oppose naive realism based on the possibility of illusion, hallucination or error.

If this presupposition is rejected, then it is no longer a question of whether or not we perceive the world as it is in itself directly, but a question of whether or not we perceive the world directly. The latter does not require a superhuman form of perception that can infallibly see "behind" the appearance of the world, but simply a form of perception that provides an appearance of the world, fallible or not. -

flannel jesus

2.9kbut a question of whether or not we perceive the world directly. — Luke

flannel jesus

2.9kbut a question of whether or not we perceive the world directly. — Luke

I don't understand what work the word "directly" is doing in that sentence. Why not just say, "whether or not we perceive the world"? How does adding the word "directly" change the meaning of it? -

Luke

2.7kIt becomes a question of whether we can perceive the world or only an intermediary of the world.

Luke

2.7kIt becomes a question of whether we can perceive the world or only an intermediary of the world. -

Luke

2.7kWhether, for example, I can see the screen in front of me, or whether I am seeing only an intermediary of the screen in front of me.

Luke

2.7kWhether, for example, I can see the screen in front of me, or whether I am seeing only an intermediary of the screen in front of me. -

Michael

16.8kYou don't see the screen; you see sensations? — Luke

Michael

16.8kYou don't see the screen; you see sensations? — Luke

Light reflects from the screen, stimulating the sense receptors in the eyes, sending signals to the brain, eliciting a visual sensation. Presumably we all agree on that.

You can call this seeing the screen or you can call this seeing a visual sensation. It makes no difference. That’s simply an irrelevant grammatical convention, and not in fact mutually exclusive.

The relevant philosophical concern is that the visual sensation is distinct from the screen, that the properties of the visual sensation are not the properties of the screen, and that it is the properties of the visual sensation that inform rational understanding, hence why there is an epistemological problem of perception. That’s the indirect realist’s argument. -

Luke

2.7kYou can call this seeing the screen or you can call this seeing a visual sensation. It makes no difference. That’s simply an irrelevant grammatical convention. — Michael

Luke

2.7kYou can call this seeing the screen or you can call this seeing a visual sensation. It makes no difference. That’s simply an irrelevant grammatical convention. — Michael

According to grammatical convention, we would normally say that we see a screen, not a "visual sensation". The "visual sensation" is the "seeing".

The relevant philosophical concern is that the visual sensation is distinct from the screen, that the properties of the visual sensation are not the properties of the screen, and that it is the properties of the visual sensation that are inform rational understanding. Hence why there is an epistemological problem of perception. That’s the indirect realist’s argument. — Michael

The indirect realist's argument is that a perception is distinct from its object (of perception)? I would have thought that we could all agree on that.

If it makes no difference whether we call it seeing the screen or seeing a visual sensation, then it should also make no difference whether we call them the properties of the screen or the properties of a visual sensation. Surely that’s simply an irrelevant grammatical convention.

It appears that you only want to argue against naive realism, which is fine, but I think I've addressed that in my post above. You follow the naive realist in adopting the presupposition that there is a "correct" way to perceive the world, which is to perceive it as it is in itself. -

Michael

16.8kIt appears that you only want to argue against naive realism, which is fine, but I think I've addressed that in my post above. — Luke

Michael

16.8kIt appears that you only want to argue against naive realism, which is fine, but I think I've addressed that in my post above. — Luke

I have yet to hear a meaningful description of non-naive direct realism. Every account so far seems to just be indirect realism but refusing to call it so.

If you accept that distal objects are not constituents of experience and so that experience does not inform us about the mind-independent nature of the world then you are accepting indirect realism, because that's all indirect realism is.

The grammatical argument over whether we should say "I feel a sensation" or "I feel a distal object" is irrelevant – and again not mutually exclusive: you can describe it as feeling pain or as feeling your skin burn or as feeling the fire. -

NOS4A2

10.2k

NOS4A2

10.2k

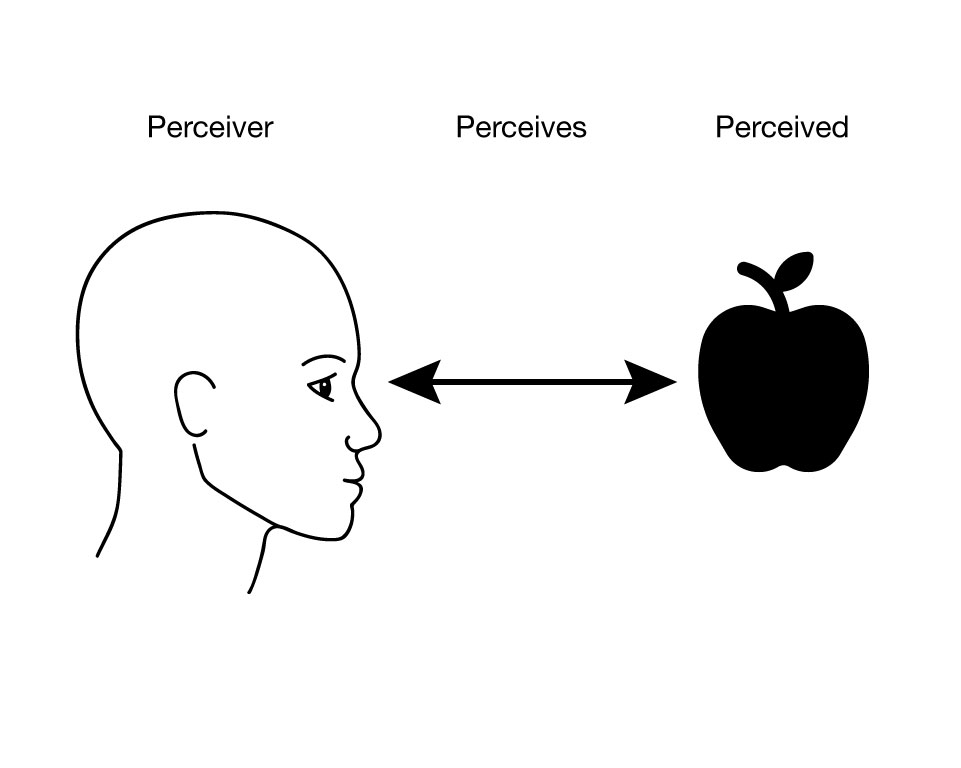

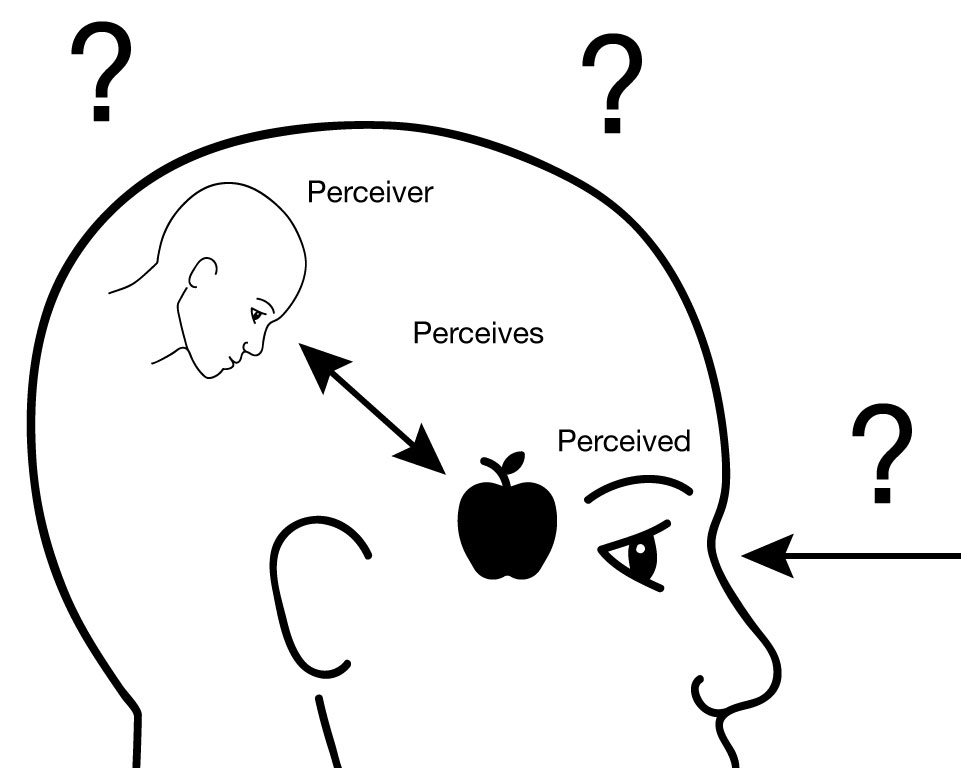

All perception is direct—we all agree there is an immediate object of perception, and that X perceives Y. The only difference between the two positions is the nature of what it is we are directly perceiving (an apple or representation of an apple), the nature of who or what perceives it (a person or a brain), and how they go about doing so.

Elucidating each position requires the use of grammar—nouns, verbs, and adjectives—each of which can be confirmed to be true or false when compared to states of affairs. So the grammar is relevant because it describes (or at least ought to) the subject of perception, the object of perception, and how both are interacting with each other.

The grammar can indicate where a position goes off the rails. For instance, upon hearing the arguments my alarm bells go off. "Well, that noun doesn't refer to anything in particular"; "that object of perception is just a reiteration of the subject and predicate, an equivocation"; "experience is treated as if a space or container in which things occur, albeit with no defined boundary or volume or location".

The imagery the grammar evokes is important, in my opinion. For me it evokes as follows:

Direct Perception

Indirect Perception

-

Luke

2.7kI have yet to hear a meaningful description of non-naive direct realism. Every account so far seems to just be indirect realism but refusing to call it so. — Michael

Luke

2.7kI have yet to hear a meaningful description of non-naive direct realism. Every account so far seems to just be indirect realism but refusing to call it so. — Michael

The naive realist defines direct perception in terms of perceiving the world as it is in itself (the WAIIII), and they say we do perceive the WAIIII.

The indirect realist also defines direct perception in terms of perceiving the WAIIII, but they say we do not perceive the WAIIII.

The non-naive direct realist agrees with the indirect realist that we do not perceive the WAIIII, but does not define direct perception in these terms. For the non-naive direct realist (or for me, at least), direct perception is defined in terms of perceiving the world, not in terms of perceiving behind the appearances of the world to the WAIIII.

Edited to add: Perceptions provide the appearances of the world (as it appears to the perceiver) so it is incoherent to talk about perceiving behind the appearances. The concept of perceiving the WAIIII is therefore incoherent, so direct and indirect perception should not be defined in terms of it.

Welcome to The Philosophy Forum!

Get involved in philosophical discussions about knowledge, truth, language, consciousness, science, politics, religion, logic and mathematics, art, history, and lots more. No ads, no clutter, and very little agreement — just fascinating conversations.

Categories

- Guest category

- Phil. Writing Challenge - June 2025

- The Lounge

- General Philosophy

- Metaphysics & Epistemology

- Philosophy of Mind

- Ethics

- Political Philosophy

- Philosophy of Art

- Logic & Philosophy of Mathematics

- Philosophy of Religion

- Philosophy of Science

- Philosophy of Language

- Interesting Stuff

- Politics and Current Affairs

- Humanities and Social Sciences

- Science and Technology

- Non-English Discussion

- German Discussion

- Spanish Discussion

- Learning Centre

- Resources

- Books and Papers

- Reading groups

- Questions

- Guest Speakers

- David Pearce

- Massimo Pigliucci

- Debates

- Debate Proposals

- Debate Discussion

- Feedback

- Article submissions

- About TPF

- Help

More Discussions

- Other sites we like

- Social media

- Terms of Service

- Sign In

- Created with PlushForums

- © 2026 The Philosophy Forum