-

wonderer1

2.4kWhat I object to with determinism as usually presented is, 'hey we (scientists) know what the real causes of everything is...' — Wayfarer

wonderer1

2.4kWhat I object to with determinism as usually presented is, 'hey we (scientists) know what the real causes of everything is...' — Wayfarer

Who really says anything remotely like that? You seem to enjoy posting quotes from people who you see as supporting your view. Why resort to a straw man in the case of views you disagree with? It comes across to me as anti-physicalist propagandizing. Why don't you provide quotes, of actual statements made by the people whose views you oppose, rather than put words in the mouth of a figment of your imagination?

That's where it becomes scientistic rather than scientific - everything has to be explainable within the procrustean bed of physical causation. — Wayfarer

I generally see people's use of "scientistic" as indicative of an anti-science bias on their part. Anyway, you are putting up a strawman again, and trying to paint physicalists with views they do not hold.

The simple fact is that you haven't considered physicalism in a charitable way, and so don't know what it is like to look at things from a physicalist perspective. It's not that "everything has to be explainable within the procrustean bed of physical causation." It that those who seriously study the causation of things, find through life experience that explanations that don't conform to the Procrustean bed, never seem to yield reliable predictions.

Science is enforced humility:

What is the core, immutable quality of science?

It's not formal publication, it's not peer review, it's not properly citing sources. It's not "the scientific method" (whatever that means). It's not replicability. It's not even Popperian falsificationism – the approach that admits we never exactly prove things, but only establish them as very likely by repeated failed attempts to disprove them.

Underlying all those things is something more fundamental. Humility.

Everyone knows it's good to be able to admit when we've been wrong about something. We all like to see that quality in others. We all like to think that we possess it ourselves – although, needless to say, in our case it never comes up, because we don't make mistakes. And there's the rub. It goes very, very strongly against the grain for us to admit the possibility of error in our own work. That aversion is so strong that we need to take special measures to protect ourselves from it.

If science was merely a matter of increasing the sum of human knowledge, it would be enough for us all to note our thoughts on blogs and move on. But science that we can build on needs to be right. That means that when we're wrong – and we will be from time to time, unless we're doing terribly unambitious work – our wrong results need to be corrected.

It's because we're not humble by nature – because we need to have humility formally imposed on us – that we need the scaffolding provided by all those things we mentioned at the start.

You don't understand the perspective, because you simply don't have the life experience required to have developed such a perspective. By all means, demonstrate something that doesn't fit the Procrustean bed, but I'm not going to hold my breath, nor spend a lot of time addressing quotes of the sort you like to post in the meantime. -

Leontiskos

5.6kThat might need reworking, but I gather you are asking about what happens at the point of death. The language "divided in two" is loaded with dualism. The common prejudice is that at death something leaves the body. I don't think that's right - rather the body stops doing stuff it once did. It no longer works in the same way. — Banno

Leontiskos

5.6kThat might need reworking, but I gather you are asking about what happens at the point of death. The language "divided in two" is loaded with dualism. The common prejudice is that at death something leaves the body. I don't think that's right - rather the body stops doing stuff it once did. It no longer works in the same way. — Banno

But does anyone disagree and claim that the body keeps working the same way after death? An appeal to a soul is an appeal to a reason why a body "stops doing stuff it once did." Plato would not have been surprised to hear that dead bodies act differently than live bodies.

(I realize this is all quite far from the point that @Fooloso4 was trying to make.)

That can be put in terms of identity. The body no longer serves to present the characteristics that made it the person it once was. In the same way one looks at a person in pain and understands that they are in pain, one understands by looking at a corpse that it no longer functions as a person. — Banno

Well, the interesting thing is that it cannot be put in terms of identity, because the identity of the body comes from the fact that it is a unified organism. Once it dies it is no longer a unity, and it is therefore no longer one thing, possessing a single identity. It will quickly decompose into a million different parts. The disintegration occurs because the "soul" (unifying principle of life) is no longer enlivening the body.

Just for fun I should add that a substantial change takes place at death, an essential corruption. When a human dies the human no longer exists, and only the corpse remains, where the human and the corpse are two fundamentally different kinds of things. Whatever "grandpa" was, he is most definitely not the thing in the casket. It is inadequate to say, "Grandpa is now functioning differently." -

Wayfarer

26.1kWhat I object to with determinism as usually presented is, 'hey we (scientists) know what the real causes of everything is...'

Wayfarer

26.1kWhat I object to with determinism as usually presented is, 'hey we (scientists) know what the real causes of everything is...'

— Wayfarer

Who really says anything remotely like that? — wonderer1

The site you provided - which is a very well-presented and well argued site - says 'nature is enough'. And as the site is devoted to naturalism, then it rejects what it says can be categorised as 'supernatural', the implication being that the natural sciences are a superior source of insight to religious beliefs or philosophies. Other examples:

The naturalist doesn't suppose human beings, complex and multi-talented though they are, transcend causal laws and explanations in their behavior.

The scope of this realm as depicted in our sciences is nothing less than staggering. It is a far more varied, complex, and vast creation than any provided by religion, offering an infinite vista of questions to engage us.

He's arguing, there is no superior source of insight to science. So that is more than 'remotely like that'; it is actually that.

I quite agree that the natural sciences are indispensable across a huge range of applications, and within certain ranges are universal - but not all questions considered by philosophy are amenable to scientific or naturalistic explanation. That is particularly so in the case of ethics and philosophy of mind. Again, that site has a very rich array of arguments in support of a kind of naturalist compatibilism. But the central thesis that humans are natural beings, devoid any faculty or attribute which can be understood as transcending nature, is itself based on a methodological assumption, which then is treated as a philosophical axiom. And that is mostly framed in the context of the perceived tension or conflict in religion vs science, the subject of a sub-section on the site, Naturalism Vs Theology.

You don't understand the perspective — wonderer1

I understand it perfectly well, thank you, and in its context it is completely unexceptionable. Nothing to do with my criticism of physicalism. -

Wayfarer

26.1kThat might need reworking, but I gather you are asking about what happens at the point of death. The language "divided in two" is loaded with dualism. The common prejudice is that at death something leaves the body. I don't think that's right - rather the body stops doing stuff it once did. It no longer works in the same way.

Wayfarer

26.1kThat might need reworking, but I gather you are asking about what happens at the point of death. The language "divided in two" is loaded with dualism. The common prejudice is that at death something leaves the body. I don't think that's right - rather the body stops doing stuff it once did. It no longer works in the same way.

— Banno

But does anyone disagree and claim that the body keeps working the same way after death? An appeal to a soul is an appeal to a reason why a body "stops doing stuff it once did." Plato would not have been surprised to hear that dead bodies act differently than live bodies. — Leontiskos

I had the idea - please correct me if I'm wrong - that in the Aristotelian tradition, 'the soul' is seen as something more like an organising principle, than a ghostly entity. That is what is meant by 'the soul is the form of the body', isn't it? I think there has been a tendency to reify that into a literal 'thinking thing' from which the issue arises of its separability from the body. -

Wayfarer

26.1k

Wayfarer

26.1k

Wonderer1 asked

Why don't you provide quotes, of actual statements made by the people whose views you oppose, — wonderer1

I did exactly that, and also presented some arguments as to why I differed with them, apparently to no avail. (Although I do recognise that piggybacking comments with gratuitous jibes directed at those you disagree with is part of your usual MO.) -

Fooloso4

6.2kgather you are asking about what happens at the point of death. — Banno

Fooloso4

6.2kgather you are asking about what happens at the point of death. — Banno

The question is perhaps as old as man.

The language "divided in two" is loaded with dualism. — Banno

It reflects the dualism that Socrates is responding to. Then as now the division of body and soul was common. As you say:

The common prejudice is that at death something leaves the body. — Banno

He uses the division of body and soul, and in doing so brings that belief into question.

I don't think that's right - rather the body stops doing stuff it once did. It no longer works in the same way. — Banno

That was observed. The question or questions, however, remain - what happens to the person? Socrates entertains two possibilities in the Apology -

1) The continued existence of the soul separate from the body

2) Oblivion. An endless, dreamless sleep.

In the Phaedo, however, he is silent about the second possibility. He does not state it explicitly, but the common assumption that underlies the first proves to be its own undoing. Socrates is not simply a soul attached for a time to some body. Socrates is a whole, a living being, that soon will no longer be alive. Soon Socrates will no longer be. -

baker

6k

baker

6k

Notice how I talk about not taking concepts out of their native contexts?, I'm advocating for semantic holism.

— baker

I've been unable to see any such advocation. Perhaps if you were to set it out more explicitly, I'd be able to follow. — Banno

Of course.Unfortunately including sacred cows and the existence of the dalet. If we are to treat Hinduism holistically, such must also be taken into account.

In contrast, ask yourself why you want to even think about reicarnation at all.

I am well aware of this tension. I actually keeps me up at night.Interesting. There's a tension between placing emphasis on autonomy while maintaining that one is culturally embedded, as you did in your reply to Joshs, ↪baker.

Indeed, and as the doctrine of reincarnation says, this is because most people are under the influence of maya, illusion, where they don't know who they really are.And yet the vast mass of humanity have no such recollection. — Banno

To be clear, I'm not using Stevenson's work as some kind of evidence for reincarnation. In fact, I think it's misleading, I dismiss it. I think it's irrelevant to what Hinduism and Buddhism teach on reincarnation/rebirth.We have a congenital difference, you and I, that leads me to think of you as credulous. I won't be able to show you - it's not just that the evidence is insufficient, but that it is incoherent.

That's a good example of what happens when a concept is taken out of its native context.Population growth also seems to be a problem for reincarnation: according to defenders of reincarnation, souls migrate from one body to another. This, in a sense, presupposes that the number of souls remains stable, as no new souls are created, they only migrate from body to body. Yet, the number of bodies has consistently increased ever since the dawn of mankind. Where, one may ask, were all souls before new bodies came to exist? (Edwards, 1997: 14). Actually, this objection is not so formidable: perhaps souls exist in a disembodied form as they wait for new bodies to come up (D’Souza, 2009: 57). — IEP Immortality

In Hindu and Buddhist teachings, the "number problem" is addressed thusly:

a living being is reincarnated/reborn

1. across various species (sometimes as a human, other times as an animal, yet other times as a deity, etc.)

2. also sometimes on other planets, not just on Earth. -

baker

6kMy reason for not believing in any form of personal rebirth or afterlife is not that there is any definitive evidence against it, but simply that I cannot make rational sense of the idea, and I cannot believe something I am incapable of even making coherent to myself. — Janus

baker

6kMy reason for not believing in any form of personal rebirth or afterlife is not that there is any definitive evidence against it, but simply that I cannot make rational sense of the idea, and I cannot believe something I am incapable of even making coherent to myself. — Janus

I don't believe in any form of afterlife (such as in Christianity or Islam), not in reincarnation, not in rebirth.

Yet I know enough about them that they all make sense to me.

I surmise that the reasons why I don't believe in any of them are:

1. Given that I am familiar enough with several afterlife/reincarnation/rebirth doctrines to the point that they all make sense to me, they very fact that this is so makes it impossible to prefer one over the other. They can't all be right, but how could one choose?

2. Conceptually, afterlife/reincarnation/rebirth doctrines (and religions in general, as a whole) are about things that precede me or contextualize me. Choosing one would be like attempting to choose my parents or the land where I was born. It's an unintelligible, impossible choice.

3. I am not a member of any religious community. I think that if I would be, this would change things for me entirely.

I think that most people who believe in reincarnation/rebirth don't believe it on account of "evidence". Most of those believers were simply raised into such religions, so it's never been an active issue for them. But I also know Buddhists, some of them even monks of many years, who use Stevenson's work as a basis for their belief in rebirth (which is actually very un-Buddhist).As you know I am not against people believing in rebirth or whatever. Obviously there can be no definitve evidence either way. — Janus

I think it has to do with a nagging concern that can be summed up as "Is this all there is to life?"What I am curious about is why people care about it, since it obviously cannot be understood to personal survival of death. Is it an irrational fear of annihilation?

The unsatisfactoriness and fleetingness of life makes them wish for something more.

Then there is also the question of justice. If one lifetime is all there is, then how can it be fair that some children die of cancer, while some criminals get to live long, happy lives. And if we are to accpet that life isn't fair, then what does this mean for our sense of morality? The topic of this thread is also "the problem of evil". -

baker

6k

baker

6k

Some children acquiesce and some don't. Not all children are equally well acculturated into the religion they are born to and raised in. For some, it's a traumatic experience (like being beaten by their religious parents and teachers), for some others, it's apparently a fairly joyous one. Families and communities are different and have various approaches to the teachings (esp. in terms of which teachings they emphasize more and in the context of what particular family and social dynamics etc.). (I've known Christians who are apparently really happy about the Gospel. I think that's bizarre. I've no idea how the do it.)But I would hesitate to claim that all children must acquiesce to what they are being taught. — Janus

I think it's similar with religious doctrines. They function as cognitive tools. The point of religious belief isn't merely to hold it, but to do something with it, to have it inform one's thoughts, words, and deeds.Language does not strike me as a good analogy since it is a tool not a belief; one does not accept or reject it but rather one learns to use it. -

baker

6kAnd it seems that we not only do not know, but have no way of determining the answer; and so we turn to mandating that it is so, instead. We make it up. — Banno

baker

6kAnd it seems that we not only do not know, but have no way of determining the answer; and so we turn to mandating that it is so, instead. We make it up. — Banno

It's similar with the way atheists of the Dawkins type don't believe in God. Their atheism is an atheism of a god that no actual theist believes in. Not because Dawkins' idea of god would be a strawman, but because it's something so abstract and so general that it doesn't match any existing theistic religion.

Similarly, the kind of disbelief in reincarnation some are displaying here is a disbelief in a notion of reincarnation that no believer in reincarnation believes in. In this case, these disbelievers' notion of reincarnation is partly a strawman, but mostly it's just based on ignorance of actual reincarnation doctrines. -

Leontiskos

5.6kI had the idea - please correct me if I'm wrong - that in the Aristotelian tradition, 'the soul' is seen as something more like an organising principle, than a ghostly entity. That is what is meant by 'the soul is the form of the body', isn't it? I think there has been a tendency to reify that into a literal 'thinking thing' from which the issue arises of its separability from the body. — Wayfarer

Leontiskos

5.6kI had the idea - please correct me if I'm wrong - that in the Aristotelian tradition, 'the soul' is seen as something more like an organising principle, than a ghostly entity. That is what is meant by 'the soul is the form of the body', isn't it? I think there has been a tendency to reify that into a literal 'thinking thing' from which the issue arises of its separability from the body. — Wayfarer

I think that's basically right, but it does get complicated. Speaking plainly, for the Aristotelian the soul is the principle that accounts for the difference between a living body and a corpse. It is the principle of life of a living body, and this includes human, animal, and plant bodies.

The question of separability arises only with rational souls (human souls), and I would have to review the strictly Aristotelian literature on that topic. My guess is that some Aristotelians accept separability and some reject it, but a common point would be that if separated souls exist they are not wholes, but rather parts (i.e. the body is an intrinsic part of the human being, and not a mere appendage). -

Leontiskos

5.6ki don't think I said or implied otherwise. — Banno

Leontiskos

5.6ki don't think I said or implied otherwise. — Banno

Here is what you said:

The common prejudice is that at death something leaves the body. I don't think that's right - rather the body stops doing stuff it once did. It no longer works in the same way. — Banno

The idea is, "Rather than something leaving the body, the body stops doing stuff it once did." Hence my <post>, noting the false dichotomy.

A similar faux pas would be, "Rather than the engine driving the car, the wheels make it move." Those who claim that the engine drives a car do not deny that the wheels make it move, and therefore such a claim is an ignoratio elenchi. -

baker

6kAnd one more thing to this:

baker

6kAnd one more thing to this:

My reason for not believing in any form of personal rebirth or afterlife is not that there is any definitive evidence against it, but simply that I cannot make rational sense of the idea, and I cannot believe something I am incapable of even making coherent to myself. — Janus

The unspoken assumptions in many of these discussion are that "a particular claim is being proposed for discussion" or "a particular claim is being proposed for belief".

In my experience, this is not how religious/spiritual people think or approach discussion of religious/spiritual topics.

For example, for traditional Hindus, an outsider talking about reincarnation would be perceived as an idle intruder, someone who is thinking and talking about things they have no business talking about, being an outsider (although it would take the Hindus quite a bit to actually say so). In traditional Hinduism, religious conversion is an unintelligible concept. For them, religion is something one is born into, like caste, and not something subject to choice.

I find that for many traditionally religious people, religious doctrines are something one either believes or doesn't believe, not something that would be subject to empirical study or experience. Those religious people who proselytize will sometimes offer some "reasons for belief", but at least some of them will also say that those reasons are just provisional, a "tool to help the unbelievers", and not actual justifications for the religious claims (for those claims are not viewed as needing justification at all). -

wonderer1

2.4kI find that for many traditionally religious people, religious doctrines are something one either believes or doesn't believe, not something that would be subject to empirical study or experience. — baker

wonderer1

2.4kI find that for many traditionally religious people, religious doctrines are something one either believes or doesn't believe, not something that would be subject to empirical study or experience. — baker

There is a pretty huge spectrum on that matter. Here in the US there is no shortage of Christians who believe that people should have Christian beliefs.

LINKThen Trump again expanded his rhetoric.

“I will implement strong ideological screening of all immigrants,” he said, reading from the teleprompter. “If you hate America, if you want to abolish Israel,” he continued, apparently ad-libbing, “if you don’t like our religion — which a lot of them don’t — if you sympathize with the jihadists, then we don’t want you in our country and you are not getting in. Right?” — Washington Post

This sort of rhetoric appeals to a high percentage of US Christians. -

Banno

30.6kNo, , that's not close.

Banno

30.6kNo, , that's not close.

I'll take your word for it, although I recall reading a similar account elsewhere, with Plato writing differing accounts for various audiences. What's curious is the way in which talk of division or of a spirit leaving the body comes so easily.The language "divided in two" is loaded with dualism.

— Banno

It reflects the dualism that Socrates is responding to. Then as now the division of body and soul was common. As you say:

The common prejudice is that at death something leaves the body.

— Banno

He uses the division of body and soul, and in doing so brings that belief into question. — Fooloso4

I want to draw attention to what is a visceral difference between how one sees a living and a dead body.

We brace ourselves against this with ritual, seeking some sort of continuity or normality. But our grief recognises the loss. -

Janus

18kGiven that I am familiar enough with several afterlife/reincarnation/rebirth doctrines to the point that they all make sense to me, they very fact that this is so makes it impossible to prefer one over the other. They can't all be right, but how could one choose? — baker

Janus

18kGiven that I am familiar enough with several afterlife/reincarnation/rebirth doctrines to the point that they all make sense to me, they very fact that this is so makes it impossible to prefer one over the other. They can't all be right, but how could one choose? — baker

I am familiar with them too, but I can't say they make sense to me beyond the fact that they are all logically possible in the sense of not being obviously self-contradictory. That said, I think the Buddhist concept on the face of it is the most incoherent. The Hindu notion of a reincarnating soul seems at first glance to make more sense to me, although that opens up all the problems associated with dualism. Resurrection is another can of worms because it involves positing an omnipotent God.

In my experience, this is not how religious/spiritual people think or approach discussion of religious/spiritual topics.

For example, for traditional Hindus, an outsider talking about reincarnation would be perceived as an idle intruder, someone who is thinking and talking about things they have no business talking about, being an outsider (although it would take the Hindus quite a bit to actually say so). — baker

I agree with this and often say that critical discussion has no place in the contexts of spiritual disciplines and religious practices, and even, as Hadot notes in the kinds of ancient philosophies which consisted of systems of metaphysical ideas meant to support "spiritual exercises". But tell that to the fundamentalists!

In any case, this is a philosophy forum where ideas and arguments are presented for critique, so if people want to present their beliefs and ideas here, they should expect questioning, criticism and disagreement. -

Wayfarer

26.1kI think I was the one who introduced 'children with past life memories' into the topic. Stevenson documented nearly 3,000 such cases over a 30-40 year period, each comprising hundreds of claims that were checked against documentary, historical sources and witnesses. Stevenson himself is careful not to claim this mass of data proves that there is such a thing as re-birth, only that his data suggests it. Furthermore, unlike mythological literature of the afterlife, these accounts have been subjected to empirical validation (in fact, apart from near-death experiences, past-life memories are the only kinds of such phenomena that can be subjected to empirical examination.)

Wayfarer

26.1kI think I was the one who introduced 'children with past life memories' into the topic. Stevenson documented nearly 3,000 such cases over a 30-40 year period, each comprising hundreds of claims that were checked against documentary, historical sources and witnesses. Stevenson himself is careful not to claim this mass of data proves that there is such a thing as re-birth, only that his data suggests it. Furthermore, unlike mythological literature of the afterlife, these accounts have been subjected to empirical validation (in fact, apart from near-death experiences, past-life memories are the only kinds of such phenomena that can be subjected to empirical examination.)

I think the interesting philosophical question is that the most common reaction to Stevenson's research is that it couldn't be true, that there must be something wrong with him or his methodology, and that it can or should be ignored.

for traditional Hindus — baker

Would this include the hundreds of millions of middle-class Indians now employed in call-centres and high technology industries in Hyderabad and the like? I've worked with quite a few IT people of Indian extraction (one of whom always wore a bindu) and, although it didn't come up much, from time to time there might have been discussions of such topics as Hindu beliefs, and they didn't seem all that reticent to me. They noted approvingly of my interest in Eastern philosophy. -

Fooloso4

6.2kI'll take your word for it, although I recall reading a similar account elsewhere, with Plato writing differing accounts for various audiences. — Banno

Fooloso4

6.2kI'll take your word for it, although I recall reading a similar account elsewhere, with Plato writing differing accounts for various audiences. — Banno

I have said this several times. For example:

here

Just as Socrates spoke differently and said different things to different people, Plato manages to say different things with the same words.

here

Socrates spoke differently to different people.

here

The two depictions of the soul in the Republic and the Phaedrus do not match up. Different stories for different occasions. Socrates says the he speaks differently to different men depending on their needs.

here

Socrates spoke differently to different people depending on their needs.

I don't recall the source I relied on though. Perhaps @Paine knows.

What's curious is the way in which talk of division or of a spirit leaving the body comes so easily. — Banno

The Greek word translated as soul is ψυχή (psykhē, Latin psyche). The Hebrew is רוח (ruach). Spirit comes from the Latin spiritus. In each case the terms mean breath. At death breath leaves the body. It is from this natural observation that these terms go on to develop mythologies, metaphysical meaning,

I want to draw attention to what is a visceral difference between how one sees a living and a dead body. — Banno

This raises an interesting question. Hunters do not react this way when they kill. They may even have the body preserved and displayed. This may have something to do with the body not being a human. Or it may be that the visceral reaction has been suppressed. How do warriors react when the kill is human? Friend or foe might make a difference. The reaction might also change with frequency.

We brace ourselves against this with ritual, seeking some sort of continuity or normality. But our grief recognises the loss. — Banno

Clergy might tell us that the deceased has gone to a better place, and some may believe this, and yet they grieve.

The other side of this is the loss of one's own life. -

Janus

18kI think the interesting philosophical question is that the most common reaction to Stevenson's research is that it couldn't be true, that there must be something wrong with him or his methodology, and that it can or should be ignored. — Wayfarer

Janus

18kI think the interesting philosophical question is that the most common reaction to Stevenson's research is that it couldn't be true, that there must be something wrong with him or his methodology, and that it can or should be ignored. — Wayfarer

I don't say it couldn't be true, but I find the anecdotal evidence in support of it unconvincing. the results could more easily, and I think more plausibly, be explained by some kind of collective memory.

My main objection, or more accurately indifference, to the ideas of rebirth or resurrection, is that they have no significance to this life, and I think this life is all that is important, given that anything beyond it can only remain nebulous.

Any fear of missing out I might feel (very little) is only relative to this life. Of course, the fear of missing out on resurrection, and especially the fear of not missing out on the alternative of eternal suffering, would be far more significant than anything rebirth has to offer in the way of fear, if only it were believable. -

Joshs

6.7k

Joshs

6.7k

Science is enforced humility:

What is the core, immutable quality of science?

It's not formal publication, it's not peer review, it's not properly citing sources. It's not "the scientific method" (whatever that means). It's not replicability. It's not even Popperian falsificationism – the approach that admits we never exactly prove things, but only establish them as very likely by repeated failed attempts to disprove them.

Underlying all those things is something more fundamental. Humility. Everyone knows it's good to be able to admit when we've been wrong about something. We all like to see that quality in others. We all like to think that we possess it ourselves – although, needless to say, in our case it never comes up, because we don't make mistakes. And there's the rub. It goes very, very strongly against the grain for us to admit the possibility of error in our own work. That aversion is so strong that we need to take special measures to protect ourselves from it.

If science was merely a matter of increasing the sum of human knowledge, it would be enough for us all to note our thoughts on blogs and move on. But science that we can build on needs to be right. That means that when we're wrong – and we will be from time to time, unless we're doing terribly unambitious work – our wrong results need to be corrected. — wonderer1

I notice that only one form of humility was mentioned here, concerned with the epistemological issue of getting the facts right or wrong. But the notion of scientism has to do with lacking a different form of humility, closely linked with a spirit of audacity. This humility doesn’t concern science as truth or falsity but its continual becoming through revolutionary changes in paradigms, and the recognition that this is not a linear, inductive or deductive progress. it a kind of shift in faith and values. It require the appreciation of science’s close proximity to philosophy, the arts , and yes, even religion in this respect. Stridently scientistic arguments by the likes of Dan Dennett, Richard Dawkins and Sean Carroll suffer from a lack of humility in this department. -

Wayfarer

26.1k:clap: The 'promethean' nature of science - 'stealing fire from the Gods' - is sometimes cited.

Wayfarer

26.1k:clap: The 'promethean' nature of science - 'stealing fire from the Gods' - is sometimes cited.

At death breath leaves the body. It is from this natural observation that these terms go on to develop mythologies, metaphysical meaning, — Fooloso4

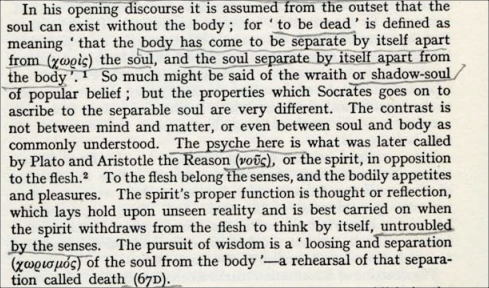

One of the earlier discussion you referenced contains a link to the Cornford book Plato's Theory of Knowledge from the introduction of which I copy (the 'opening discourse' is from the Phaedo):

I don't find that account implausible, from a philosophical perspective. It also foreshadows the later 'doctrine of the rational soul' you find in Thomas. In that later form of hylomorphism, nous is what grasps the form or principles of things, while the senses perceive its material (accidental) features.

@Leontiskos

(As a footnote, I sometimes wonder if what is meant by 'thinking' or 'reason' in the Platonic dialogues is something completely different from what we mean by thought. I think it's referring to something much more like 'insight' or 'intuitive grasp' than the passing montage of words, images and ideas that we usually designate 'thought'. "It is by seeing what justice is that one becomes just; by seeing what wisdom is, that one becomes wise.") -

Leontiskos

5.6k

Leontiskos

5.6k

Interesting. I have a hard time pinning Plato down. Like @Fooloso4 said, the dialogues are very nuanced, and say different things at different times, to different interlocutors. In any case, Fooloso was never claiming that death necessarily involves a dualism. Banno's misunderstanding drove that line. -

Banno

30.6k

Banno

30.6k

Perhaps I was not clear. I am happy with what you have said here.I have said this several times. — Fooloso4

I wasn't referring to any reaction of regret; just the simple fact that a dead body is different to a live one. I was attempting to draw a parallel with Wittgenstein's observations concerning pain. Too long a bow, it seems.Hunters do not react this way when they kill. — Fooloso4

The ubiquitous account is that something has left the body, implying a dualism. My point was that it is of equal validity to say that the body no longer does what it once did, avoiding the dualism.

Anyway, this thread would seem to be joining so many recent topics by heading off into exegesis of the ancients. Not my area.

Welcome to The Philosophy Forum!

Get involved in philosophical discussions about knowledge, truth, language, consciousness, science, politics, religion, logic and mathematics, art, history, and lots more. No ads, no clutter, and very little agreement — just fascinating conversations.

Categories

- Guest category

- Phil. Writing Challenge - June 2025

- The Lounge

- General Philosophy

- Metaphysics & Epistemology

- Philosophy of Mind

- Ethics

- Political Philosophy

- Philosophy of Art

- Logic & Philosophy of Mathematics

- Philosophy of Religion

- Philosophy of Science

- Philosophy of Language

- Interesting Stuff

- Politics and Current Affairs

- Humanities and Social Sciences

- Science and Technology

- Non-English Discussion

- German Discussion

- Spanish Discussion

- Learning Centre

- Resources

- Books and Papers

- Reading groups

- Questions

- Guest Speakers

- David Pearce

- Massimo Pigliucci

- Debates

- Debate Proposals

- Debate Discussion

- Feedback

- Article submissions

- About TPF

- Help

More Discussions

- Other sites we like

- Social media

- Terms of Service

- Sign In

- Created with PlushForums

- © 2026 The Philosophy Forum