-

Wayfarer

26.1kIn 1845, Michael Faraday introduced the concept of the electromagnetic field. Nowadays electromagnetic fields are known to be omnipresent, even in so-called empty space, and atomic particles are conceived of as 'excitations of fields' rather than as the indivisible and independently-existent point-particles (or atoms) of pre-modern science.

Wayfarer

26.1kIn 1845, Michael Faraday introduced the concept of the electromagnetic field. Nowadays electromagnetic fields are known to be omnipresent, even in so-called empty space, and atomic particles are conceived of as 'excitations of fields' rather than as the indivisible and independently-existent point-particles (or atoms) of pre-modern science.

This leads me to a further question: what if there are types of fields other than electromagnetic? There is, for instance, the theory of morphogentic fields which is contested, but which is still being considered (e.g. Morphogenic fields: A coming of age.) These are related to, but not the same as, Sheldrake's controversial 'morphic fields' theory (and please spare me the obligatory Sheldrake-bashing.)

But there are many other examples. Consider the case of Frank Brown, a US scientist who situated oysters in an isolated environment in Evanston Illinois, in the middle of the continental US, and was amazed to find that they gradually synchronised their opening and closing times with the high tides adjusted for their location, even though they were completely isolated from external world. The linked article says that Frank Brown was more or less ostracised for theorising that oysters could somehow sense the time, with the preferred explanation being that they must have some kind of organic chronometer on a biomolecular level (but according to that extract, the point remains moot).

Morphogenetic field effects in biology are invoked to explain how amphibians, for example, can re-grow exact copies of amputated limbs. Then of course there are the very well-documented travels of migratory birds who return to their home grounds thousands of kilometers from their feeding grounds and eels who migrate thousands of kilometers to breed. It is nowadays thought that these creatures can navigate by electromagnetic fields or possibly orient themselves with respect to the sun. Likewise the phenomenon of horses and other herd animals who panic and show strange behaviours prior to earthquakes (ref). They too are thought to detect subtle changes in the electromagnetic field - but what if the field they're detecting is not actually electromagnetic at all?

So the question this brings up is - what if fields of other kinds - mental or biological - are ubiquitous, in the same way that electromagnetic fields are? And then even if they were, how could they be detected? In the case of electromagnetism Faraday and his successors were able to demonstrate electromagnetic effects with great precision - but these are just the kinds of effects which the physics, and the instruments, were able to detect and predict. If there were such things as biological or mental fields, they may not be detectable by electronic instruments at all. (After all, persons with metal detectors will generally only ever unearth metal artefacts, but this doesn't prove that "all artefacts are metal").

All of this kind of speculation tends to be taboo in science - Sheldrake is regarded as a crank or at least maverick, Frank Brown was professionally shunned, and so on. The mainstream consensus is that oysters, for instance, have no known way of sensing the tides table, so there must be some molecular mechanism which accounts for their actions. Yet I can't help but sense the resonance with Einstein's rejection of 'spooky action at a distance', one of the apparent implications of quantum mechanics, and a rare case in which Einstein's intuitions were later shown to have been wrong by the Alain Aspect experiments.

I'm interested in any sources for these kinds of ideas - for instance the Frank Brown research was reported in this book which I feel a strong urge to add to my already-groaning bookshelves. (And if anyone is able to download a copy of that paper I'd be most obliged, as I don't have institutional login privleges.) -

T Clark

16.1kThis leads me to a further question: what if there are types of fields other than electromagnetic? — Wayfarer

T Clark

16.1kThis leads me to a further question: what if there are types of fields other than electromagnetic? — Wayfarer

The idea of a field is not all that exotic - it just means there is a specific value of some property at all locations of space, at least within a given area. There are definitely fields other than electromagnetic ones. There are gravitational fields and quantum fields. If I understand correctly, and that's a fairly big if, a quantum field is the one you're talking about when you reference "atomic particles are conceived of as 'excitations of fields'.."

Consider the case of Frank Brown, a US scientist who situated oysters in an isolated environment in Evanston Illinois, in the middle of the continental US, and was amazed to find that they gradually synchronised their opening and closing times with the high tides adjusted for their location, even though they were completely isolated from external world. — Wayfarer

I'm not sure I understand. There are no tides in Evanston, Illinois. For an oyster in a location with tides, differences in hydrostatic pressure with different water depths could be one possible explanation for coordination of shell opening. Another might be sensitivity to the flow of water associated with tides.

I am definitely a skeptic about any ideas of exotic or hidden fields that have important effects which have not been identified. -

Wayfarer

26.1ka quantum field is the one you're talking about when you reference "atomic particles are conceived of as 'excitations of fields'.." — T Clark

Wayfarer

26.1ka quantum field is the one you're talking about when you reference "atomic particles are conceived of as 'excitations of fields'.." — T Clark

Right, that's what I was thinking of.

There are no tides in Evanston, Illinois. — T Clark

That's the point - that's what made it an anomaly. Frank Brown took oysters from the Eastern seaboard and sealed them in a tank in Evanston with no exposure to sunlight or the elements. Over the next month or so, their opening/closing timelines shifted to match what the tide would be in that location, had there been tides.

I am definitely a skeptic about any ideas of exotic or hidden fields that have important effects which have not been identified. — T Clark

Right. That is also what befell Frank Brown.

Brown concluded that the organisms were sensitive to external geophysical factors, perhaps minute fluctuations in gravity, or even subtle forces that hadn’t yet been discovered. ...Such ideas were viewed as threatening by his peers. Several of them had fought to have their own work on daily cycles taken seriously by other scientists. Their professional respectability hinged on using rigorous, reproducible methods, and basing their theories on impeccable physical principles of cause and effect; Brown’s claims of mysterious forces were dangerous nonsense that jeopardized the field. His measurements weren’t accurate enough, they insisted, or he was seeing patterns in his highly complex data that simply weren’t there. Yet Brown was charismatic and articulate, and he was swaying public opinion.

So that's the point I'm exploring. Why is it that some types of explanations were regarded as scientifically appropriate or sound or acceptable, and others were not? -

Jack Cummins

5.7k

Jack Cummins

5.7k

It is good to see you again on the forum and I think that many have missed you. As for the fields, my interpretation is that they have wide reaching implications for the understanding of the way in which consciousness evolves. The fields are like memories in nature and about links between minds. It may be about patterns which exist in nature, as opposed to being 'supernatural'. Sheldrake's ideas which he is continuing to develop are fairly radical, with some support for aspects of extrasensory perception and even a leaning towards panpsychism. -

Wayfarer

26.1kthanks Jack, appreciated. I've always liked Sheldrake but I'm mindful of his critics, although their stridency is revealing. I suppose the specifically philosophical point is that, until electromagnetic field effects were discovered, nobody really had any idea of 'fields' as such, but I wonder if there might be other kinds of fields and if so how they would manifest and how they would be detected.

Wayfarer

26.1kthanks Jack, appreciated. I've always liked Sheldrake but I'm mindful of his critics, although their stridency is revealing. I suppose the specifically philosophical point is that, until electromagnetic field effects were discovered, nobody really had any idea of 'fields' as such, but I wonder if there might be other kinds of fields and if so how they would manifest and how they would be detected. -

universeness

6.3k

universeness

6.3k

I find this categorisation of field types helpful:

1. Scalar fields, these describe spin-0 particles such as the Higgs boson.

2. Spinor fields, these describe spin-1/2 particles, these describe for example the elementary fermions, like the leptons and quarks.

3. Vector fields, these describe spin-1 particles like for example the photon-field.

But I think QFT and 'strings' will eventually be 'component' parts of a t.o.e. -

Metaphysician Undercover

14.8kThis field of study (pun intended) is very problematic. Physicists understand the transmission of energy in electromagnetic fields as waves. They also know that a wave is the movement of a substance. This produced the idea that there was an aether, as a medium, within which the electromagnetic waves are active.

Metaphysician Undercover

14.8kThis field of study (pun intended) is very problematic. Physicists understand the transmission of energy in electromagnetic fields as waves. They also know that a wave is the movement of a substance. This produced the idea that there was an aether, as a medium, within which the electromagnetic waves are active.

The current attitude in the scientific community is to deny the reality of the medium, and produce models, or representations of the wave action which do not include the medium, space-time being a separate somewhat static background. This renders the true nature of the wave action which is involved here impossible to understand. You can see that a true understanding would require that either we stop representing electromagnetic energy as a wave action, or else we include within the representations, the substance (aether) which is active. Of course the former is unrealistic, and that leaves us with the task of trying to determine the true nature of medium which is the substance within which, those waves exist. Denying the reality of this substance, and continuing with the current enterprise of faulty models is not the answer.

I'm interested in any sources for these kinds of ideas — Wayfarer

There is a large volume of speculative information on the web, which begins from the assumption that all physical existence is vibrations of the underlying medium (the medium here being roughly equivalent to what scientists call space-time). That the entire Cosmos is a collection of vibrations is a very ancient idea, extending back through the Pythagoreans and beyond. You'll find it very evident in Plato, The Phaedo for example, where the idea that the soul is a harmony which creates the unity of the material body is discussed. If you start searching through "vibration" theories on the web, it's a very daunting task to separate the tidbits of valuable information from the masses of propaganda, as is the case with much religious material.

Perhaps you might prepare yourself by listening to one of the greatest pop songs ever written: "Good Vibrations"

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=apBWI6xrbLY -

Metaphysician Undercover

14.8kA quick search tells me that one of the recurring themes in the various vibration theories, is that things such as living beings somehow adjust their vibrational field to maintain harmony with their environment.

Metaphysician Undercover

14.8kA quick search tells me that one of the recurring themes in the various vibration theories, is that things such as living beings somehow adjust their vibrational field to maintain harmony with their environment. -

SophistiCat

2.4kSo this is not about fields at all. The actual question being asked could be stated as follows:

SophistiCat

2.4kSo this is not about fields at all. The actual question being asked could be stated as follows:

Can a researcher postulate an unknown force of nature (to use a somewhat dated expression) in order to explain anomalous results of an experiment?

Short answer: No.

Longer answer: Not so fast.

Anomalous results are ubiquitous in science. Any student who has performed lab experiments has obtained anomalous results on occasion, be it a couple of outliers or an entire data set. The same goes for most professional experimentalists. Needless to say, the overwhelming majority of these occasions do not betoken a scientific discovery, let alone some fantastic new force of nature. That alone should tell you that jumping to conclusions is unwarranted.

There are many potential reasons for anomalous results: equipment malfunction, external interference, faulty experimental design, faulty analysis, even scientific malpractice. Any honest researcher will try to rule these out first. That means critically analyzing your experiment for potential faults, and if none stand out, conducting additional experiments with tighter controls and more data points. Most of the time, this results in either eliminating the anomaly or explaining it in terms of known science.

Only once these most likely causes for the anomaly are ruled out does the search for a new explanation begin. But what could such an explanation look like? There are as many answers as there have been scientific discoveries, but one thing is common to all of them: merely positing "subtle forces that hadn’t yet been discovered" won't cut it, even if you make up a sciency-sounding name for these subtle forces, such as "morphic fields." The reason is that such "explanations" explain precisely nothing. Stripping off superfluous and unwarranted verbiage, all they say is that "there is something that accounts for these results being just so." Well, duh. -

Wayfarer

26.1kThere are as many answers as there have been scientific discoveries, but one thing is common to all of them: merely positing "subtle forces that hadn’t yet been discovered" won't cut it, even if you make up a sciency-sounding name for these subtle forces, such as "morphic fields." — SophistiCat

Wayfarer

26.1kThere are as many answers as there have been scientific discoveries, but one thing is common to all of them: merely positing "subtle forces that hadn’t yet been discovered" won't cut it, even if you make up a sciency-sounding name for these subtle forces, such as "morphic fields." — SophistiCat

According to the abstract for the article I mentioned in the OP, morphogenetic fields have a long history, and address specific problems in biology (although I haven’t been able to access the paper in full.)

There’s a well–known interview with an editor of Nature who had remarked in his review that Rupert Sheldrake’s first book which introduced his morphic fields was ‘a book for burning’. When asked later as to why he made this remark, he said that ‘Sheldrake is putting forward magic instead of science, and that can be condemned in exactly the language that the Pope used to condemn Galileo, and for the same reason. It is heresy.’ And why it is ‘heresy’ is because there is no discernible medium in which Sheldrake’s ‘habits of nature’ can be formed or transmitted. In his terms, there is no mechanism for such formations, such as that provided by genetic transmission. However, interestingly, one rather more mainstream figure whose ideas may be convergent with Sheldrake’s in some respects was C.S. Pierce, who also posited that ‘nature forms habits’. But the point is, these proposals undermine the predominantly mechanistic explanations that underlie the scientific worldview, and that’s why they’re deemed heretical. -

Jack Cummins

5.7k

Jack Cummins

5.7k

Even though Sheldrake speaks of fields his understanding is parallel with Jung's idea of the collective unconscious, as memory inherent in nature. I discovered his writing while I was reading Jung and thinking about Western religious ideas. What I found helpful was that it was a way of connecting the ideas of Jung with nature and spatial reality rather than the collective becoming an abstract metaphysical void of disembodied spirits. Now, neuroscience seems to be the way of connecting perception and reality, especially in relation to the idea of qualia. But, the morphic fields provide another interesting angle, but it does seem that many disregard his writings.

It is probably because he does have a leaning towards the esoteric. I was in 'Watkins', an esoteric bookstore in London and saw that he has written some new books on consciousness. I avoided the temptation to buy any on that occasion but I would like to read the development of his ideas because I have only read his early work, mainly 'The Presence of the Past'. I read some of, 'The Sense of Being Stared At' and it does seem that so many people can pick up if they are being stared at from behind. It may involve the subliminal mind and it that this is connected to the existence of morphic fields. -

jgill

4k3. Vector fields, these describe spin-1 particles like for example the photon-field — universeness

jgill

4k3. Vector fields, these describe spin-1 particles like for example the photon-field — universeness

You are giving this as an example of a VF, right? -

Metaphysician Undercover

14.8kThat objects placed near each other tend to synchronize their vibrations is a well known scientific fact, observed with pendulums for hundreds of years. The following article references a number of relatively recent experiments and describes the discovery of what is called "chimera states":

Metaphysician Undercover

14.8kThat objects placed near each other tend to synchronize their vibrations is a well known scientific fact, observed with pendulums for hundreds of years. The following article references a number of relatively recent experiments and describes the discovery of what is called "chimera states":

https://www.quantamagazine.org/physicists-discover-exotic-patterns-of-synchronization-20190404/ -

Wayfarer

26.1kThere's an essay on Sheldrake's website about reaction to his books, called 'The Sense of being Glared At' :-)

Wayfarer

26.1kThere's an essay on Sheldrake's website about reaction to his books, called 'The Sense of being Glared At' :-) -

Jack Cummins

5.7k

Jack Cummins

5.7k

I didn't know that there is a Sheldrake website, so thanks for telling me that. It may prevent me from building up more and more piles of paper books! -

Wayfarer

26.1kthanks, interesting article. I'm a fan of that writer, she produces some excellent material. (Notice there's a headline 'Good Vibrations' :-) )

Wayfarer

26.1kthanks, interesting article. I'm a fan of that writer, she produces some excellent material. (Notice there's a headline 'Good Vibrations' :-) ) -

bert1

2.2kIf two things are present at all points in space, aren't they the same thing? I guess they can be separated conceptually, one kind of effect can be distinguished from another. Presumably they can be separated mathematically, I have no idea. But ontologically, if 'two' fields are totally co-extensive, there's a sense in which they are one thing, no?

bert1

2.2kIf two things are present at all points in space, aren't they the same thing? I guess they can be separated conceptually, one kind of effect can be distinguished from another. Presumably they can be separated mathematically, I have no idea. But ontologically, if 'two' fields are totally co-extensive, there's a sense in which they are one thing, no? -

Metaphysician Undercover

14.8k

Metaphysician Undercover

14.8k

Scientific American has an article about the resonance theory of consciousness which came up in my search, titled "The Hippies Were Right: It's All about Vibrations, Man! -

Wayfarer

26.1kBut ontologically, if 'two' fields are totally co-extensive, there's a sense in which they are one thing, no? — bert1

Wayfarer

26.1kBut ontologically, if 'two' fields are totally co-extensive, there's a sense in which they are one thing, no? — bert1

The point I was trying to make in the OP is that while magnetic field effects can be easily demonstrated by observing the behaviour of iron filings the existence of such things as 'morphogenetic fields' is much more difficult to establish.

The former can be demonstrated in a primary-school classroom with a magnet, some iron filings, and a sheet of paper, whereas the latter relies on sophisticated inferences from the observation of biological reproduction.

And as electromagnetic fields were described by Maxwell's equations, their effects can be observed to conform with predictions, which are nowadays fundamental in the operations of almost every electrical device.

Whereas even if there are field effects in biological systems, they might be much harder to observe because of the complexity of organisms and the range of possible explanations. That's where Sheldrake is at least relevant - at least he claims to have demonstrated morphic resonance, even if his many critics reject his findings. Again, morphogenic (or morphogenetic) field theory differs from Sheldrake's - whilst not being universally accepted it's also not regarded as fringe as I understand it.

There was a guy on one of the old forums, Alan McDougall, who always used to say that everything was waves and vibrations. I said we could test it - 'I'll wave, and you vibrate! :-) -

Metaphysician Undercover

14.8k

Metaphysician Undercover

14.8k

I would think that a theory such as morphic resonance would require some sort of hierarchy of fields. Massive particles, protons, and neutrons for example, by the law of inertia, have a lot stronger 'staying power', for temporal continuity of existence, than a particle with very little mass like an electron, or a photon with no mass. Therefore the massive particle should have a substantially stronger resonance, with its specific vibration much more deeply ingrained into its own being, as well as into the fiber of the universe. This would be required to support the continued unity of that massive particle in its temporal extension. I believe that in quantum physics what supports the temporal extension of a massive particle is called the strong interactive force. It is an unusual force because it cannot be observed to be limited by distance. -

deletedmemberbcc

208Scientific American has an article... titled "The Hippies Were Right: It's All about Vibrations, Man! — Metaphysician Undercover

deletedmemberbcc

208Scientific American has an article... titled "The Hippies Were Right: It's All about Vibrations, Man! — Metaphysician Undercover

:lol: That's good, I like that. -

jgill

4kBut ontologically, if 'two' fields are totally co-extensive, there's a sense in which they are one thing, no? — bert1

jgill

4kBut ontologically, if 'two' fields are totally co-extensive, there's a sense in which they are one thing, no? — bert1

Consider two force fields in the complex plane, one f(z)=2z+3 and the other f(z)=1-z. When computing work done in moving along the same contour (path) in the plane, the results are different. Are these fields "one thing"?

Biological fields? Who knows? :chin: -

universeness

6.3kYou are giving this as an example of a VF, right? — jgill

universeness

6.3kYou are giving this as an example of a VF, right? — jgill

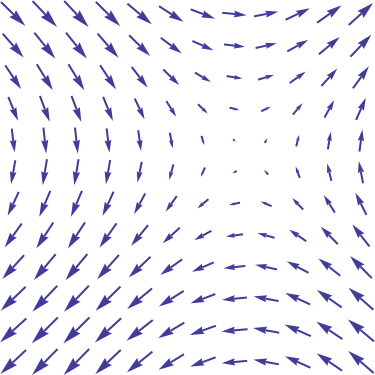

Yes, just based on a definition such as, from Wiki:

In vector calculus and physics, a vector field is an assignment of a vector to each point in a subset of space. For instance, a vector field in the plane can be visualised as a collection of arrows with a given magnitude and direction, each attached to a point in the plane. Vector fields are often used to model, for example, the speed and direction of a moving fluid throughout space, or the strength and direction of some force, such as the magnetic or gravitational force, as it changes from one point to another point.

Photons have magnitude and direction in the sense that they have an extent (vector length) and move in the direction of their momentum. Is this not correct? -

universeness

6.3k

universeness

6.3k

I think this is one of the fundamental aspects of string theory, that any 4 co-ordinate point (x,y,z,t), t=time, in spacetime can manifest any standard particle/field excitation, and the fundamental involved is some kind of (possibly inter-dimensional) vibration(string?)(excitation?)(waveform?) and there may be conditions where two points (coordinates), can be connected (entangled), in such a way that the (excitation/string etc) propagates/travels via undulation etc but its 'connected state' does not travel it just displays in accordance with the 'entangled system' when measured, regardless of the distance between them. -

universeness

6.3k'I'll wave, and you vibrate! — Wayfarer

universeness

6.3k'I'll wave, and you vibrate! — Wayfarer

I would have answered you with NO! You vibrate and I'll wave! -

Metaphysician Undercover

14.8kI believe that in quantum physics what supports the temporal extension of a massive particle is called the strong interactive force. — Metaphysician Undercover

Metaphysician Undercover

14.8kI believe that in quantum physics what supports the temporal extension of a massive particle is called the strong interactive force. — Metaphysician Undercover

According to Wikipedia, this is the "gluon field". It is actually eight different fields, one for each "colour charge". Each of the eight fields has a "timelike" component and three "spacelike" components. The existence of the proposed fields is supported by gauge theory which employs a principle of invariance resulting in symmetries. -

jgill

4kPhotons have magnitude and direction in the sense that they have an extent (vector length) and move in the direction of their momentum. Is this not correct? — universeness

jgill

4kPhotons have magnitude and direction in the sense that they have an extent (vector length) and move in the direction of their momentum. Is this not correct? — universeness

Those little wiggly buggers have lives of their own, the intricacies of which are beyond me. I was just checking to make sure you were not defining VFs by a specific example. :cool:

Welcome to The Philosophy Forum!

Get involved in philosophical discussions about knowledge, truth, language, consciousness, science, politics, religion, logic and mathematics, art, history, and lots more. No ads, no clutter, and very little agreement — just fascinating conversations.

Categories

- Guest category

- Phil. Writing Challenge - June 2025

- The Lounge

- General Philosophy

- Metaphysics & Epistemology

- Philosophy of Mind

- Ethics

- Political Philosophy

- Philosophy of Art

- Logic & Philosophy of Mathematics

- Philosophy of Religion

- Philosophy of Science

- Philosophy of Language

- Interesting Stuff

- Politics and Current Affairs

- Humanities and Social Sciences

- Science and Technology

- Non-English Discussion

- German Discussion

- Spanish Discussion

- Learning Centre

- Resources

- Books and Papers

- Reading groups

- Questions

- Guest Speakers

- David Pearce

- Massimo Pigliucci

- Debates

- Debate Proposals

- Debate Discussion

- Feedback

- Article submissions

- About TPF

- Help

More Discussions

- If we're in a simulation, what can we infer about the possibility of ending up in Hell?

- The end of History or the possibility of 100% original new political systems?

- Does Peter Singer Eliminate the Possibility for Supererogation?

- Questions regarding possibility, necessity, laws of nature and Scientific reductionism

- Other sites we like

- Social media

- Terms of Service

- Sign In

- Created with PlushForums

- © 2026 The Philosophy Forum