-

Wayfarer

26.1kI don't think many people are thinking about it, although I'd be glad to be proven wrong. Aristotelian or scholastic realism, represented by Aquinas, does have its contemporary defenders in the form of 'analytical Thomism'. They're not generally identified as idealist, although they're surely no friends of materialism either. But it should be recalled that the very term 'idealism' only came into use in the 17th century, it was never used by the ancients or medieval philosophers.

Wayfarer

26.1kI don't think many people are thinking about it, although I'd be glad to be proven wrong. Aristotelian or scholastic realism, represented by Aquinas, does have its contemporary defenders in the form of 'analytical Thomism'. They're not generally identified as idealist, although they're surely no friends of materialism either. But it should be recalled that the very term 'idealism' only came into use in the 17th century, it was never used by the ancients or medieval philosophers.

Incidentally I thought I'd mention the Essentia Foundation https://www.essentiafoundation.org/ which is associated with Bernardo Kastrup and also Donald Hoffman, among many others. It's a think-tank of sorts, dedicated to current idealist philosophy and science. -

Bartricks

6kYou haven't read him, have you?

Bartricks

6kYou haven't read him, have you?

Tell me, did Berkeley say it? What was he referring to?

You don't know. I know you don't know, because no one who has read him would leave out the context.

So, what is he talking about?

I will tell you. He is talking about sensations. It is the essence of a sensation that it be sensed. That is, sensations exist as mental activity.

He was not saying that it is the essence of anything's being that it be sensed. That would not make sense at all. -

Count Timothy von Icarus

4.3k

Count Timothy von Icarus

4.3k

You are confusing idealism with anti-realism. They are not the same thing. There is an entire subset of idealism called "objective idealism," that accepts the reality of external objects. This is probably the largest subset of idealism actually. Objective idealism doesn't deny that diseases exists, so there is no problem here. The key German Idealists were very into the science of their day actually. What they rejected was the claim that matter was ontologically basic and represents discrete "things in themselves."

Mental/physical is a false dichotomy in their opinion. Only subjective idealism is the claim that "everything is mental," in the sense most people would take that claim. The better way to think of objective/Absolute idealism is the claim that: "the subjective and objective are part of a unified whole." One cannot be understood except in reference to the other. This is also not dualism, it is a monism; we have different emerging from one thing, but two things.

Schelling wrote a lot. What I have from my notes is:

"

1. Ego is the highest potency of the powers of Nature.

2. Nature is the source of creative intelligence.

3. Reason is able to abstract from the subjectivity of the ego to reach the point of pure subject/object identity.

Nature is actually the self in disguise. After all, all of nature is only experienced through the self. But the self necessarily posits that which it is not, thus we get nature (Schelling following Fichte here). Schelling departs from Fichte in not having the self at the center of everything. Instead, the claim is that nature and the self represent natural dualities, and the whole of the entirety of being (the Absolute) is an outgrowth of/resultant from these contradictions.

The fulfilment of nature is to become object to itself (here we can see the influence on Hegel)." My handwriting is pretty bad, but I think that's what I came away with.

This seems pretty foreign now-a-days, but actually the claim isn't too far off from those many modern philosophers and scientists make when they claim that talking about various phenomena from "the view from nowhere," or the "God's eye view," is misleading at best, meaningless at worst. Objects and entities only exist in the mind. Empiricism is necessarily the study of how experience is. The positing of a discrete, ontologically basic world that fits the models we deduce from experience is a profound overreach and mistake.

What the older idealists add, which is now less of a focus, is an ontological argument about the nature of being. That the differences in being we experience are logically necessitated by the fact that there is something rather than nothing.

That and they tend to start by focusing on the self for building up their arguments, which is less popular today. But I think when you get rid of all the strange terminology and vivid metaphors, 19th century idealism's core arguments aren't that far from modern versions, they are just couched in very different language. -

Gregory

5k

Gregory

5k

It seems to me that the problem of "something rather than nothing" only has force if matter is real. If all that exists is thought sensations, I don't see the problem applying. What do you think? -

Marchesk

4.6kYou are confusing idealism with anti-realism. They are not the same thing. There is an entire subset of idealism called "objective idealism," that accepts the reality of external objects. — Count Timothy von Icarus

Marchesk

4.6kYou are confusing idealism with anti-realism. They are not the same thing. There is an entire subset of idealism called "objective idealism," that accepts the reality of external objects. — Count Timothy von Icarus

But there is also a subjective idealism that rejects objective reality since they don't locate ideas in the mind of some supreme or universal mind. It's just individual subjective experiences. We've had some on here before. -

Count Timothy von Icarus

4.3k

Count Timothy von Icarus

4.3k

I don't see how that works. You still have a world full of concepts, symmetries, cause and effect, etc. Why this plethora of entities and endless variety instead of nothing?

If the world around us shows us causes preceding effects it is natural to ask: "what causes things to be?"

What the Boehme inspired idealists try to do is show how being emerges from logical necessity. You don't need a demiurge shaping the world based on some sort of Platonic blueprint, you just need for there to be something and not nothing. This then sets up the being/nothing contradiction, resulting in our experienced world of becoming. The rest, all the differences and possibilities of our world, flows from logical necessity.

Hegel takes this to its most complete form, having physical science, cognition, and history flowing from this necessity and progressing to the point where all being becomes known object to itself, finally resolving all contradictions. -

Count Timothy von Icarus

4.3kFor another example of an "immaterial" ontology there is the claim that reality is fundamentally mathematical. Talk of "physical" structures is then extraneous. Unlike many other forms of idealism, this analysis does not start with the self/subjective experience.

Count Timothy von Icarus

4.3kFor another example of an "immaterial" ontology there is the claim that reality is fundamentally mathematical. Talk of "physical" structures is then extraneous. Unlike many other forms of idealism, this analysis does not start with the self/subjective experience.

What I find interesting about this is that one of the attempts to provide a fully scientific metaphysics: Every Thing Must Go, walks right up to this line, almost states it as an apparent fact, then opts to shoehorn the "physical" back in:

According to OSR, if one were asked to present the ontology of the world according to, for example, GR one would present the apparatus of differential geometry and the field equations and then go on to explain the topology and other characteristics of the particular model (or more accurately equivalence class of diffeomorphic models) of these equations that is thought to describe the actual world. There is nothing else to be said, and presenting an interpretation that allows us to visualize the whole structure in classical terms is just not an option. Mathematical structures are used for the representation of physical structure and relations, and this kind of representation is ineliminable and irreducible in science...

What makes the structure physical and not mathematical? That is a question that we refuse to answer. In our view, there is nothing more to be said about this that doesn’t amount to empty words and venture beyond what the PNC allows. The ‘world-structure’ just is and exists independently of us and we represent it mathematico-physically via our theories.

That's a head scratcher; it certainly recalls Hemple's Dilemma.

The only subjective idealist I am all that familiar with is Berkley, and for him these are tied together by the mind of God. My intuition is that these systems would tend to be very idiosyncratic. -

Gregory

5kI don't think many people are thinking about it, although I'd be glad to be proven wrong. Aristotelian or scholastic realism, represented by Aquinas, does have its contemporary defenders in the form of 'analytical Thomism'. They're not generally identified as idealist, although they're surely no friends of materialism either. But it should be recalled that the very term 'idealism' only came into use in the 17th century, it was never used by the ancients or medieval philosophers.

Gregory

5kI don't think many people are thinking about it, although I'd be glad to be proven wrong. Aristotelian or scholastic realism, represented by Aquinas, does have its contemporary defenders in the form of 'analytical Thomism'. They're not generally identified as idealist, although they're surely no friends of materialism either. But it should be recalled that the very term 'idealism' only came into use in the 17th century, it was never used by the ancients or medieval philosophers.

Incidentally I thought I'd mention the Essentia Foundation https://www.essentiafoundation.org/ which is associated with Bernardo Kastrup and also Donald Hoffman, among many others. It's a think-tank of sorts, dedicated to current idealist philosophy and science. — Wayfarer

My problem with Hoffman is that you can't encode at a very basic level the idea of "seeing reality in itself" and "seeing only an appearance" into game theory (which he works on). The subject must accept the object as it is and from there and from then only can you say that it perceives it wrongly. Only on the condition that it can see rightly can it see wrongly (in terms of science).

Maybe the medievalists were idealist though. Their rejection of nominalism suggests this, and Kant's Critique of Judgment seems to suggest this to me as well -

Count Timothy von Icarus

4.3k

Count Timothy von Icarus

4.3k

it doesn't make sense to say "perceiving is perceived"

How so? It's bad writing to say, "I experienced experiencing the pain" but it isn't illogical. -

Gregory

5kI don't see how that works. You still have a world full of concepts, symmetries, cause and effect, etc. Why this plethora of entities and endless variety instead of nothing?

Gregory

5kI don't see how that works. You still have a world full of concepts, symmetries, cause and effect, etc. Why this plethora of entities and endless variety instead of nothing?

If the world around us shows us causes preceding effects it is natural to ask: "what causes things to be?"

What the Boehme inspired idealists try to do is show how being emerges from logical necessity. You don't need a demiurge shaping the world based on some sort of Platonic blueprint, you just need for there to be something and not nothing. This then sets up the being/nothing contradiction, resulting in our experienced world of becoming. The rest, all the differences and possibilities of our world, flows from logical necessity.

Hegel takes this to its most complete form, having physical science, cognition, and history flowing from this necessity and progressing to the point where all being becomes known object to itself, finally resolving all contradictions. — Count Timothy von Icarus

But with what first principle do you start with. Descartes argues there must exist something that is at least as great as all our ideas. This he calls God, and he goes on to reason that this God must not deceive. So it was like going around a triangle, from himself, to God, to the world. Hegel starts with being, which he says is also a nothing, because it is pure becoming. This seems to say matter is necessary and the way to understand "why" there is something is almost mechanical: because there is a cause behind every cause -

Count Timothy von Icarus

4.3k

Count Timothy von Icarus

4.3k

I haven't looked in his models in any depth, but I can see how it works if you have the condition that an organism looking for resources so that it can reproduce can only store a finite amount of information about its environment.

If the amount of information in the enviornment exceeds that which the organism can store then the organism must have some method for compressing information.

Likewise, if the organism has finite computational power than it will also need to optimize how it compresses information about its environment.

Already we have established that the organism won't represent the enviornment with full accuracy. The next step is to see if the compression methodology will hew towards as accurate a representation as possible or one optimized for fitness. This is where the game theory models and computer simulations come into play in that they show how more complex organism will find optimal solutions that move further away from lossless compression and towards compression techniques that are optimized for reproduction.

It varies by person. Fichte starts with the apparent self. Schelling and later Hegel start with being itself. I think the latter approach is the best technique. How do you get anything more ontologically basic than being itself? -

Gregory

5k

Gregory

5k

They will never to able to say how much information a brain can process because it is first person experience alone that knows how it processes information. Also how the noumena reveals itself is not science but phenomenology. Knowledge is inexplicable -

Gregory

5k

Gregory

5k

Also, how can they map the terrain and compare with storage capacity if there is no terrain? -

spirit-salamander

2681. How we can appear to have separate people with unique conscious experiences. — Tom Storm

spirit-salamander

2681. How we can appear to have separate people with unique conscious experiences. — Tom Storm

This is a very good question, perhaps the most important of all, to which an idealist must give a very thorough and detailed answer. Kastrup's answer to the question is very wild and speculative. The superior mind suffers from a multiple personality disorder. That's what he thinks.

Then there is the problem that the superior mind is looking through all of our eyes. But how can it accomplish all this at the same time? If this mind currently experiences my subjectivity, how should it then be able to experience yours at the same moment? It seems inconsistent. Because a consciousness of something is absolutely private and focused. If the Master Mind does not participate in our minds, then it might be redundant.

2. How reality (such as it is) appears to be consistent and regular. — Tom Storm

If it were not consistent and regular, there would be no experience in the mind. The mind operates with categories, which constitute the formal structure of the external world. And without such categories, experience of consistency and regularity would not be possible. This is the Kantian answer.

3. How evolution tracks to idealism. — Tom Storm

Schopenhauer, an idealist, considered them incompatible. Because evolution starts from the reality of time. But idealism excludes this. Time is given only ideally in a subject. Without a subject there is no temporally extended evolution. The whole millions of years of evolution are without subject actually only an instantaneous moment.

The question would be, how does the universal mind perceive evolution? With our understanding and feeling of time?

4. Whether we require a universal mind for idealism to be coherent. Other models? — Tom Storm

Yes, without this universal mind there would be no idealism. But a realism. There would be a plurality of animal minds.

Another human being, for example, whom I perceive empirically, might then be a kind of rendering of his momentary mind status into my mind.

And for plants and the elements one would have to assume an unconscious, which exists in and for itself. Panpsychism could be an alternative.

Obviously, idealists have a hard time with the unconscious. In the strict sense, there must not be such a thing for them. Everything must be conscious, at least in the universal mind.

5. Whether the Copenhagen Interpretation and the perceived flaws in a materialist metaphysics have been key in a recent revival of idealism? — Tom Storm

This Copenhagen quantum view would say that things, unobserved, are in a state of being able to be brought to mind. They are a pure potential.

But the ontological status of such a potential is somewhat obscure. On the other hand, everything is supposed to be already observed in the universal mind. This mind should always already bring the wave function to collapse.

6. What might be the role of human beings in an idealist model? — Tom Storm

The role of people's illnesses must be reconsidered in any case. Most of them are then likely to be merely psychosomatic. But all would have to be due to a mental disorder. Factors like repression, guilt, stress are then responsible for most of the diseases.

This is a logical consequence of idealism. Materialism sees everything only physically, idealism sees everything mentally.

Therefore, it is only consistent when the idealist Otto Weininger says the following:

"Every illness is guilt and punishment; all medicine must become psychiatry, care-of-the-soul. It is something immoral, i.e., unconscious, that leads to illness, and each illness is cured as soon as it is inwardly recognized and understood by the sick person himself." -

Tom Storm

10.9kThanks for your considered answers.

Tom Storm

10.9kThanks for your considered answers.

Kastrup's answer to the question is very wild and speculative. The superior mind suffers from a multiple personality disorder. That's what he thinks. — spirit-salamander

I think his idea may be more nuanced that this. He says experiences of individual consciousness are dissociated alters of universal mind - which is not metacognitive and entirely instinctive. My sense is he uses dissociative personality disorder more as a metaphor. But you are right, it is entirely speculative.

The mind operates with categories, which constitute the formal structure of the external world. — spirit-salamander

Yes.

Most of them are then likely to be merely psychosomatic. But all would have to be due to a mental disorder. Factors like repression, guilt, stress are then responsible for most of the diseases. — spirit-salamander

Interesting and controversial. Maybe the word metal disorder is a bit too strong. What are we to make of schizophrenia , say vis-à-vis diabetes? What are we to make of the word mental when all is mental?

The question would be, how does the universal mind perceive evolution? With our understanding and feeling of time? — spirit-salamander

Wouldn't time simply be another way in which mentation appears to us on the dashboard of physicalism? Isn't time one of those Kantian structures we bring to our understanding of experience and reality. Perhaps time in this model is our understanding of universal mind 'thinking'. -

Count Timothy von Icarus

4.3k

Count Timothy von Icarus

4.3k

Hoffman is a realist. As a scientist, he's not going to get hung up on metaphysical challenges to the existence of the external world. His goal is to challenge unexamined assumptions about that external world.

He takes a que from Daniel Dennett's "Darwin's Dangerous Idea." The core idea there is that, regardless of whether the central dogma of genetics holds up, or even the entire field of biology, we nonetheless have a theorem of how intricate complexity that seems to suggest a "designer," can come about with no such designer. The concept of natural selection works just as well for understanding why we see the types of physical things we do as it does for evolution. We don't see exotic matter (composed of four and even five quarks) because it isn't stable. This is also why we don't find certain elements or molecules in nature. Ockham's Razor suggests natural selection over design when it comes to complex systems.

The theorem of natural selection, "Darwin's universal acid," can explain selection even if most of what we think we know about the world is wrong.

Hoffman assumes the external world exists because all empirical evidence tells us it does. He is looking for fundemental flaws in how our senses represent the world because empiricism has also show us that our senses mislead us about reality at a fundemental level, and the history of science has shown us how our preconceptions have frequently allowed us to miss answers right in front of our faces.

With those as a given, the only extra assumptions you need for the theory he is testing is:

A. The enviornment (everything except the organism), contains more information than the organism does.

B. The organism cannot store an infinite amount of information and lacks an infinite amount of processing power.

There are, of course, objections to the reality of the physical world that don't seem resolvable. He is rejecting radical skepticism in that sense.

Hoffman goes through the objection I think you are getting at, i.e. that his argument is self refuting, in his book. "If you say we don't know the real world, how can you know we're wrong?"

The answer is that the logic of his argument is "if p then not q." This does not require one to have a full, absolute definition of p. "-X * -X is a positive number," does not require one to have defined X. The logic of multiplication is that two negatives multiplied together produces a positive number.

The logic of his argument is the same. Fitness versus truth theorem is saying that natural selection will favor representations geared towards representing information in terms of fitness. You don't need to define what truth is to have a theorem that says selection will favor representations that do not favor it.

One example he uses is a simulation where a "critter" has to find food to survive and reproduce. One set of critters sees the absolute value of food in each cell they can move to. The other sees only a color pallet, darker if a square has more food than the one it is currently on, lighter if it has less food than their current location. This second model gets the critter more useful information with a fraction of the information.

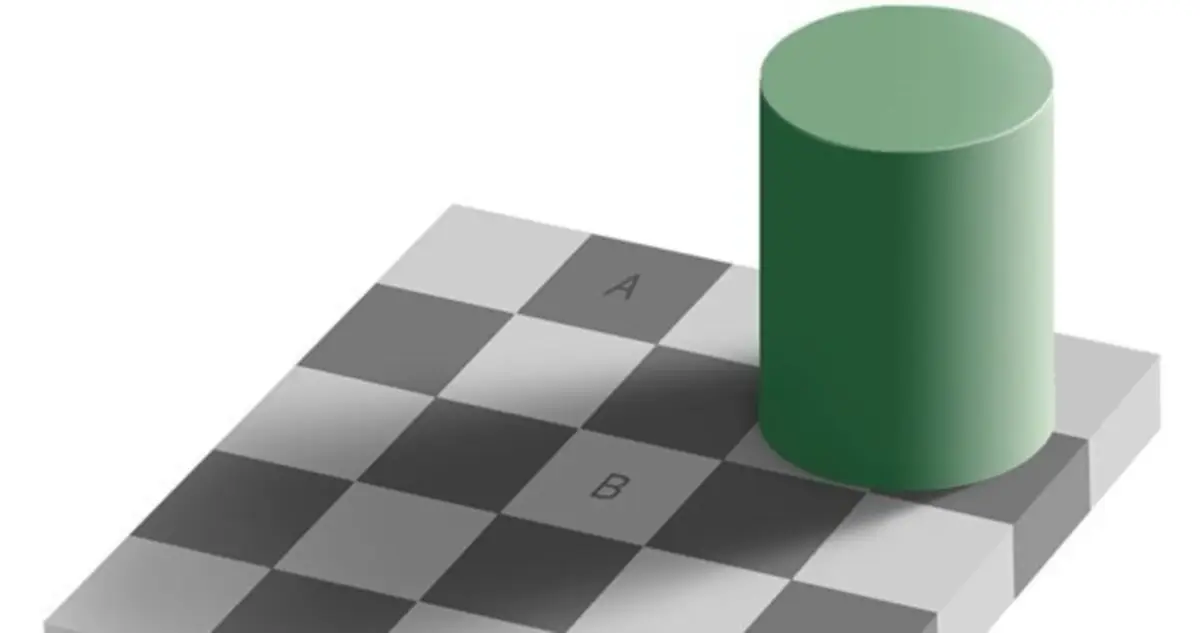

And this is also how our sensory systems actually seem to work. Wear color shaded glasses and your perspective will quickly adapt to them. Look at the picture below and you'll see square A as a different shade from square B. In a truth based system, they should appear exactly the same because they are the same.

This is all psych 101 and not terribly interesting. The more unique idea is that discrete objects, three dimensional space, etc. is simply a more deeply engrained illusion. Science is hamstrung by these persistent illusions and our tendency to project models that work with our perceptual system into reality. Thus we'll look for how neurons cause minds and forget that neurons aren't actually discrete systems and that there is no evidence that they produce anything like minds without glial cells, CSF, oxygenated blood, etc.

I think he is missing something though. Given the enviornment can change so drastically, it would seem to me that there would be merit in anchoring perceptions closer to truth somehow. I think this might be why animals evolved discrete senses that are processed separately from one another and experienced quite discretely.

He gives synthesesia as an example of how our senses don't reflect reality. The argument goes "if the number four is blue for some people and the shape of a triangle is rough textured, this shows how far off our senses can get." He sees these as an advantageous adaptations because many artists and people with high intelligence have them.

I don't think it is so simple. I think our senses are kept separate for a reason. Our senses are kept discrete as a way of cross checking perceptions and getting closer to reality (even if we still don't get very close.) If you perceive yellow as "light and airy," you might carry something yellow you might otherwise not and waste precious calories because your sense of sight is too entangled with your sense of touch. Deception is common in nature and discrete senses help ferret out deception. A bug might look visually identical to a stick to a predator, but their hearing might be able to detect the insects' internal moments and allow it to score those calories by eating the insect nonetheless.

That said, this anchoring doesn't have to keep us very close to reality, it just keeps us close enough. -

Wayfarer

26.1kThe more unique idea is that discrete objects, three dimensional space, etc. is simply a more deeply engrained illusion. Science is hamstrung by these persistent illusions and our tendency to project models that work with our perceptual system into reality. — Count Timothy von Icarus

Wayfarer

26.1kThe more unique idea is that discrete objects, three dimensional space, etc. is simply a more deeply engrained illusion. Science is hamstrung by these persistent illusions and our tendency to project models that work with our perceptual system into reality. — Count Timothy von Icarus

That's where Charles Pinter's book Mind and the Cosmic Order has some interesting things to say. He says that all sentient creatures up to and including humans negotiate their environment by seeing in 'gestalts' which are ordered wholes. But these gestalts don't exist in the physical world, they're wholly and solely the creation of the animal mind. He doesn't say that the external world doesn't exist, only that the way in which it exists is devoid of features, structure and form, which are imputed to it by the mind.

However what appears missing in both Hoffman and Pinter's ideas is an account of reason. Humans are distinct from other creatures in having meta-cognition - they are able to examine their own cognition and ask questions about it through deductive reasoning. This suggests it is possible to arrive at a kind of understanding which is not simply given by way of sensory data (which is the ancient conception of rationalist philosophy).

But it is interesting how both support the model of the mind as a constructive process that creates, generates or builds our world-picture, which seems to me to irrevocably disrupt the view of naive realism.

(Also might be of interest that Hoffman is one of the academic advisors to Kastup's Essentia Foundation.)

Hoffman is a realist — Count Timothy von Icarus

How does that square with this statement from his interview:

The central lesson of quantum physics is clear: There are no public objects sitting out there in some preexisting space. As the physicist John Wheeler put it, “Useful as it is under ordinary circumstances to say that the world exists ‘out there’ independent of us, that view can no longer be upheld.” -

spirit-salamander

268Wouldn't time simply be another way in which mentation appears to us on the dashboard of physicalism? — Tom Storm

spirit-salamander

268Wouldn't time simply be another way in which mentation appears to us on the dashboard of physicalism? — Tom Storm

So mentation is timeless, that is, without succession? The universal mind has no dashboard of physicalism? The universal mind is unbounded mentation?

If one answers yes to all, then there is no evolution in and of itself. Our dashboard then fabricates evolution out of the time- and space-less. Evolution would be just a story we tell ourselves. -

Wayfarer

26.1kScience is hamstrung by these persistent illusions and our tendency to project models that work with our perceptual system into reality. — Count Timothy von Icarus

Wayfarer

26.1kScience is hamstrung by these persistent illusions and our tendency to project models that work with our perceptual system into reality. — Count Timothy von Icarus

Q: If snakes aren’t snakes and trains aren’t trains, what are they?

Hoffman: Snakes and trains, like the particles of physics, have no objective, observer-independent features. The snake I see is a description created by my sensory system to inform me of the fitness consequences of my actions. Evolution shapes acceptable solutions, not optimal ones. A snake is an acceptable solution to the problem of telling me how to act in a situation. My snakes and trains are my mental representations; your snakes and trains are your mental representations.

Realist, eh? ;-) -

Bartricks

6kThat's what you got from what I said? You think I don't understand Berkeley?

Bartricks

6kThat's what you got from what I said? You think I don't understand Berkeley?

So, just to be clear, you think what I said was wrong, do you? So, when he said "Their esse is percipi" - so, their being is to be perceived - you think he was talking about all things and not just sensations?

It's just that he's really clear on this - clear on pretty much everything, in fact, as you'd know if you'd read him - and so it's a bit odd that you think I'm misunderstanding him. Only someone who knew nothing about Berkeley and had just read a wiki page written by a confident ignoramus would think he was talking about being in general as opposed to the being of sensations. That's how it seems to me - someone who has read Berkeley. Odd. Yet you think I don't understand him.

As you no doubt know, the quote ' "their esse is percipi" occurs in paragraph 3 of the principles, so perhaps correct my misunderstanding by explaining how the words surrounding it do not mean precisely what I said, and not at all what you said.

Do you see as well how he didn't actually say "to be is to be perceived"? He said "Their esse is percipi". That means "their being is to be perceived". And the 'their' refers to what....? Sensations. As you'd know if understood him. Which you don't. Demonstrably. -

Count Timothy von Icarus

4.3k

Count Timothy von Icarus

4.3k

Throughout his book he refers to his belief that there is "something" out there. That to me bespeaks realism. I'm not sure if his opinions have since changed, but I don't see how that quote would necessarily rule out realism. In Wheeler's participatory universe and later iterations by other physicists there are not definite "objects" or "space" before observation/interaction, but observation also doesn't generate what it finds wholly on its own. There are rules as to how the actual emerges from the possible through these interactions (allowing that they are still incomplete models). So that "something" is very strange in comparison to naive realism, but it is also still quite far from a model where the self wholly generates that which it finds around it. -

Wayfarer

26.1kIn Wheeler's participatory universe and later iterations by other physicists there are not definite "objects" or "space" before observation/interaction, but observation also doesn't generate what it finds wholly on its own. — Count Timothy von Icarus

Wayfarer

26.1kIn Wheeler's participatory universe and later iterations by other physicists there are not definite "objects" or "space" before observation/interaction, but observation also doesn't generate what it finds wholly on its own. — Count Timothy von Icarus

Neither does it do so in Kant's philosophy.

So that "something" is very strange in comparison to naive realism, but it is also still quite far from a model where the self wholly generates that which it finds around it. — Count Timothy von Icarus

Which is referred to as 'subjective idealism', and usually associated with Berkeley, which Kant took pains to differentiate himself from.

If realism understands sensory perception to be a veridical representation of mind-independent objects then it certainly is ruled out by these considerations. Hoffman calls his position 'conscious realism':

Conscious Realism is described as a non-physicalist monism which holds that consciousness is the primary reality and the physical world emerges from that. The objective world consists of conscious agents and their experiences. "What exists in the objective world, independent of my perceptions, is a world of conscious agents, not a world of unconscious particles and fields. Those particles and fields are icons in the MUIs of conscious agents but are not themselves fundamental denizens of the objective world. Consciousness is fundamental.

Plainly an idealist philosophy in my reckoning. -

Tom Storm

10.9kIf one answers yes to all, then there is no evolution in and of itself. Our dashboard then fabricates evolution out of the time- and space-less. Evolution would be just a story we tell ourselves. — spirit-salamander

Tom Storm

10.9kIf one answers yes to all, then there is no evolution in and of itself. Our dashboard then fabricates evolution out of the time- and space-less. Evolution would be just a story we tell ourselves. — spirit-salamander

You'll need to read Kastrup more closely to get a better explanation that I can provide. I'm neither an idealist, nor a philosopher, so for me all this more like trying to understand the plots of various stories. Kastrup is committed to evolution and to matter being an illusion. What all this means in terms of coherence and big ticket philosophical notions like time, being and becoming, I can't tell you. -

Tom Storm

10.9kHe says that all sentient creatures up to and including humans negotiate their environment by seeing in 'gestalts' which are ordered wholes. But these gestalts don't exist in the physical world, they're wholly and solely the creation of the animal mind. He doesn't say that the external world doesn't exist, only that the way in which it exists is devoid of features, structure and form, which are imputed to it by the mind. — Wayfarer

Tom Storm

10.9kHe says that all sentient creatures up to and including humans negotiate their environment by seeing in 'gestalts' which are ordered wholes. But these gestalts don't exist in the physical world, they're wholly and solely the creation of the animal mind. He doesn't say that the external world doesn't exist, only that the way in which it exists is devoid of features, structure and form, which are imputed to it by the mind. — Wayfarer

I don't have time to read the book, but does he speculate at the nature of those gestalts? Are they arbitrarily built into the evolutionary process, or more of a symbiotic relationship between animals and nature (whatever what is)? -

180 Proof

16.4k

180 Proof

16.4k -

Agent Smith

9.5kIs it possible to disprove idealism? No according to science; yes according to Laozi! :snicker:

Agent Smith

9.5kIs it possible to disprove idealism? No according to science; yes according to Laozi! :snicker: -

Wayfarer

26.1kAs far as the science goes he’s pretty mainstream evolutionary theory. But I do note in the final chapter, he makes the point that all living processes are interpretive - he seems to allude to biosemiosis although he doesn’t use that term. But the basic idea is that even the simplest creatures recognise objects in their environment even if in very basic forms compared to those of higher animals. This is the basis of all evolved cognitive systems including h. Sapiens. You could say that our cognitive systems designate what ‘things’ are.

Wayfarer

26.1kAs far as the science goes he’s pretty mainstream evolutionary theory. But I do note in the final chapter, he makes the point that all living processes are interpretive - he seems to allude to biosemiosis although he doesn’t use that term. But the basic idea is that even the simplest creatures recognise objects in their environment even if in very basic forms compared to those of higher animals. This is the basis of all evolved cognitive systems including h. Sapiens. You could say that our cognitive systems designate what ‘things’ are.

And it is one book well worth reading. It's quite brief, very direct and to the point. Phenomenology of Spirit, it ain't. :-) (Here's the amazon page. You will note the positive review - they're all 5 star - by yours truly.)

Welcome to The Philosophy Forum!

Get involved in philosophical discussions about knowledge, truth, language, consciousness, science, politics, religion, logic and mathematics, art, history, and lots more. No ads, no clutter, and very little agreement — just fascinating conversations.

Categories

- Guest category

- Phil. Writing Challenge - June 2025

- The Lounge

- General Philosophy

- Metaphysics & Epistemology

- Philosophy of Mind

- Ethics

- Political Philosophy

- Philosophy of Art

- Logic & Philosophy of Mathematics

- Philosophy of Religion

- Philosophy of Science

- Philosophy of Language

- Interesting Stuff

- Politics and Current Affairs

- Humanities and Social Sciences

- Science and Technology

- Non-English Discussion

- German Discussion

- Spanish Discussion

- Learning Centre

- Resources

- Books and Papers

- Reading groups

- Questions

- Guest Speakers

- David Pearce

- Massimo Pigliucci

- Debates

- Debate Proposals

- Debate Discussion

- Feedback

- Article submissions

- About TPF

- Help

More Discussions

- Other sites we like

- Social media

- Terms of Service

- Sign In

- Created with PlushForums

- © 2026 The Philosophy Forum