-

Wayfarer

26.1kBertrand Russell wrote "That which many different thoughts of whiteness have in common is their object, and this object is different from all of them". — RussellA

Wayfarer

26.1kBertrand Russell wrote "That which many different thoughts of whiteness have in common is their object, and this object is different from all of them". — RussellA

That is contained in Russell's chapter The World of Universals, which I referred to earlier.

I'm interested in Aristotelian/Thomistic realism. 'Realism' in this context is completely different to what we mean by 'realism' nowadays. Modern realism is the conviction that objects exist independently of any mind and that the world that science explores exists independently of any act of observation.

Scholastic realism believes that universals exist 'in the mind of God'. The way I would interpret that is to say that universals are what is real for any rational intelligence, but that they're only perceptible by the mind. In other words, they're not dependent on your mind or mine, but they can only be perceived by a rational mind. As such, they provide the superstructure of reason, so to speak - the framework within which judgements are made. That is the sense in which reason is transcendent - it transcends the distinction between self-and-world, and self-and-other.

I think when you say that logic is 'in the world', what you actually mean is that you look at the world through logic. That I would agree with. Logic is constitutive of the way we understand and navigate the world. Accordingly it's neither 'in' the mind, nor 'in' the world, but is a major part of the framework within which we navigate the world.

The problem with modern empiricism is that it won't see this, because its gaze is always directed outwards, towards objects, which it believes are alone real. That is what 'materialism' is. This is what is behind the blind spot of science:

Behind the Blind Spot sits the belief that physical reality has absolute primacy in human knowledge, a view that can be called scientific materialism. In philosophical terms, it combines scientific objectivism (science tells us about the real, mind-independent world) and physicalism (science tells us that physical reality is all there is). Elementary particles, moments in time, genes, the brain – all these things are assumed to be fundamentally real. By contrast, experience, awareness and consciousness are taken to be secondary. -

RussellA

2.6k“what do you think of “whiteness” — Mww

RussellA

2.6k“what do you think of “whiteness” — Mww

Abstract nouns are part of physicalism

If I hear the word "whiteness", in my mind I link the physical word "whiteness" with several physical objects in the world, such as snow, paper, milk, chalk, each of which has the physical property of being white.

It is interesting that the abstract noun "whiteness" can be explained as the product of a set of physical events - a physical link, a physical word, a physical object and a physical property.

IE, abstract nouns is an example of a universal that doesn't require dualism as an explanation.

white is not an object in the world. — Mww

White light is an object in the world

I agree that white is not an object in the world, as it is an adjective, though I would still argue, as I wrote before, "white light is a physical object"

An object is white if it emits electromagnetic radiation composed of a fairly even distribution of all of the frequencies in the visible range of the spectrum, ranging from 750 to 400nm

Consider red light. Red light is electromagnetic radiation of 750nm. Red light is a physical thing that is visible, tangible and relatively stable in form.

White light is the set of violet light, blue light, cyan light, green light, yellow light, orange light and red light. Such a set is visible, tangible and relatively stable in form.

The definition of an object is anything that is visible or tangible and is relatively stable in form.

IE, it follows that white light fulfils the definition of an object.

The world is the existence of things, so the simultaneous thing and no-thing cannot be a condition of the world — Mww

Humans may invent many logical systems, but only that logical system which corresponds to what has been discovered in the world is accepted and used

Humans are able to invent numerous logical systems. For example, I could invent a logical system whereby i) a single identity can exist and not exist at the same time, ii) a statement can be true and false at the same time, iii) one plus one equals three. Tomorrow, I could invent a totally new logical system.

The question is why is one invented logical system accepted and used rather than another.

The answer is that logical system which corresponds with what has been discovered in the world.

IE, Humans may invent many logical systems, but only that logical system which corresponds to what has been discovered in the world is accepted and used.

Metaphors are never sufficient for knowledge; only the literal will suffice. — Mww

I would say that to date we have no literal knowledge of anything, meaning that there is no alternative but for the metaphor to suffice.

As the saying goes "Getting knowledge about something is like making a map of a place or like travelling there. Teaching someone is like showing them how to reach a place".

-

javra

3.2kWhite light is an object in the world

javra

3.2kWhite light is an object in the world

I agree that white is not an object in the world, as it is an adjective, though I would still argue, as I wrote before, "white light is a physical object"

An object is white if it emits electromagnetic radiation composed of a fairly even distribution of all of the frequencies in the visible range of the spectrum, ranging from 750 to 400nm

Consider red light. Red light is electromagnetic radiation of 750nm. Red light is a physical thing that is visible, tangible and relatively stable in form.

White light is the set of violet light, blue light, cyan light, green light, yellow light, orange light and red light. Such a set is visible, tangible and relatively stable in form.

The definition of an object is anything that is visible or tangible and is relatively stable in form.

IE, it follows that white light fulfils the definition of an object. — RussellA

I wonder how you would account for the occurrence of extra-spectral colors in the purple-magenta range, for - not being part of the (visible) electromagnetic light spectrum - they don't seem to satisfy your requirement for being "objects in the world".

Color circle (RGB)

Crossover1370, CC BY-SA 4.0 <https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-sa/4.0>, via Wikimedia Commons -

Janus

18kMany of the discoveries of modern quantum physics defy logic, for instance the 'wave-particle' nature of subatomic bodies. — Wayfarer

Janus

18kMany of the discoveries of modern quantum physics defy logic, for instance the 'wave-particle' nature of subatomic bodies. — Wayfarer

It's not true that the wave/particle duality "defies logic" it merely defies our understanding of physicality.

So I dispute that as a general matter that we do see what 'things really are', even if we know enough to know a tree or an apple when we see one. — Wayfarer

What could it mean to "see things as they really are"? Are you not making an unwarranted assumption that things "really are some ultimate way". Why should that be necessary? -

Mww

5.4k“what do you think of “whiteness”

Mww

5.4k“what do you think of “whiteness”

— Mww

If I hear the word "whiteness", in my mind I link the physical word "whiteness" with several physical objects in the world, — RussellA

Which is not what the question asks, as pre-conditioned by what you shouldn’t do.

————-

I could invent a logical system whereby a single identity can exist and not exist at the same time — RussellA

You could invent a logic but couldn’t imagine whiteness?

————-

The question is why is one invented logical system accepted and used rather than another. The answer is that logical system which corresponds with what has been discovered in the world. — RussellA

Maybe, but probably much more likely that discoveries by humans correspond to the logical system intrinsic to humans. We don’t invent logic; we are logical. We merely invent the representations of its necessary systemic conditions.

So.....go ahead and try inventing a logic without using the logic with which you are naturally imbued.

————-

I would say that to date we have no literal knowledge of anything, meaning that there is no alternative but for the metaphor to suffice. — RussellA

We have no absolute knowledge, meaning there is no alternative but for contingent knowledge to suffice.

Knowledge is the highest degree of relative certainty, certainty literally is what is the case relative to the time of it. Exactly the opposite of metaphor.

I understand your literal/metaphorical dichotomy has purchase in a non-representational system, which is, oddly enough, self-defeating, in that literal and metaphor are each themselves representations. And even if they weren’t, it is far from established, that a non-representational system holds over a representational one as the whole of human intelligence qua rational thought.

As the saying goes "Getting knowledge about something is like making a map of a place or like travelling there. Teaching someone is like showing them how to reach a place". — RussellA

Whatever bonehead said that didn’t heed its weakness. Knowledge is literally making a map; teaching is metaphorically giving a map. The map made is pure experience; the map given is the opposite in the form of rote instruction.

But I get it, it’s how you claim knowledge of red flowers in vases.....because somebody told you so. Somebody showed you how to get from physical object in the world to what you should call it from then on. And you never bothered to ask yourself how that happened, and apparently, no one ever gave you a map that took you to a place you didn’t want to go.

Your system works well enough, as long as there’s no glitches. Just as soon as there is one.....for which there is ample historical precedent....that kind of system cannot sustain itself. -

RussellA

2.6kI wonder how you would account for the occurrence of extra-spectral colors in the purple-magenta range, for - not being part of the (visible) electromagnetic light spectrum - they don't seem to satisfy your requirement for being "objects in the world". — javra

RussellA

2.6kI wonder how you would account for the occurrence of extra-spectral colors in the purple-magenta range, for - not being part of the (visible) electromagnetic light spectrum - they don't seem to satisfy your requirement for being "objects in the world". — javra

Are extra-spectral colours "objects in the world" ?

Taking magenta as an example of an extra-spectral colour

To my understanding, in our eyes we have three kinds of cones configured to receive red, green and blue/violet light. We perceive magenta when both our red and blue/violet cones fire together. Magenta does not exist in the visible electromagnetic spectrum, it only exists in our conscious perception.

The are are two meanings to "object in the world"

The first meaning is from the viewpoint of an observer of the "object". For example, I observe a rock in front of me, and the rock is "an object in the world"

The second meaning is independent of any observer. For example, I am sure that on Mars there is a rock that has never been observed, yet is still an "object in the world".

Do relations ontologically exist in the world

An object is a whole comprising relationships between its parts.

A "rock" is a whole thing made up of parts, typically minerals, which are made up of atoms, which in their turn is made up of subatomic particles, such as bosons etc.

Whether relations have an ontological existence in the world is debated.

FH Bradley used a regress argument against the ontological existence of external relations.

However Russell dismissed Bradley’s argument on the grounds that philosophers who disbelieve in the reality of external relations cannot possibly interpret those numerous parts of sciences which appear to be committed to external relations.

Terminology of Idealism, Direct Realism and Indirect Realism

Idealism = the world only consists of ideas, ideas are the only reality, and there is no external reality.

Direct Realism = our senses provide us with direct awareness of the external world, and the world derived from our sense perception should be taken at face value.

Indirect Realism = our conscious experience is not of the real world itself but of an internal representation of the real world

In Idealism, there are no "objects in the world"

In Idealism, as there is no external world, there are no "objects in the world"

In Realism, whether one believes "objects in the world" exist or not depends on one's belief in the ontological existence of relations

If relations do have an ontological existence in the world, then a "rock" exists both as "an object in the world" and in the mind.

If relations don't have an ontological existence in the world, then a "rock", which is a relation between its parts, cannot have ontological existence in the world. As we are talking about rocks, they do exist in the mind.

Summary

Both red and blue/violet physically exist in the world as electromagnetic radiation.

Magenta is a relationship between red and blue/violet.

The question is, in what way does magenta exist as an "object in the world".

If Idealism is true, then magenta isn't an "object in the world"

If relations don't ontologically exist, then magenta isn't an "object in the world"

If relations do ontologically exist, then magenta is an "object in the world"

I personally don't believe relations have an ontological existence in the world for a couple of reasons, and therefore, for me, extra-spectral colours only exist in the mind and therefore are not "objects in the world" -

Agent Smith

9.5kIt looks like

Agent Smith

9.5kIt looks likeallscience is wrong if dualism is true (physically unaccounted for energy, re conservation of energy). Science is, at the end of the day, about matter & energy and how they behave and interact. Laws exist and these will be broken/violated if nonphysical minds interact, causally, with physical systems. Reminds me of The Invisible Man, poltergeists, paranormal phenomena, etc. Science failing to explain...look there for the nonphysical. -

sime

1.2kScience is a practical means for relating and translating different perspectives, and isn't descriptive of perspectives per-se, due to the fact that perspectives are a meta-logical concept that are external to the inter-subjective concept called 'scientific investigation'. Science isn't troubled by the fact that our perspectival uses of language come into conflict with our shared linguistic conventions , because science's concerns are only inter-subjective.

sime

1.2kScience is a practical means for relating and translating different perspectives, and isn't descriptive of perspectives per-se, due to the fact that perspectives are a meta-logical concept that are external to the inter-subjective concept called 'scientific investigation'. Science isn't troubled by the fact that our perspectival uses of language come into conflict with our shared linguistic conventions , because science's concerns are only inter-subjective. -

RussellA

2.6kModern realism is the conviction that objects exist independently of any mind............Scholastic realism believes that universals exist 'in the mind of God'. The way I would interpret that is to say that universals are what is real for any rational intelligence, but that they're only perceptible by the mind — Wayfarer

RussellA

2.6kModern realism is the conviction that objects exist independently of any mind............Scholastic realism believes that universals exist 'in the mind of God'. The way I would interpret that is to say that universals are what is real for any rational intelligence, but that they're only perceptible by the mind — Wayfarer

What are objects

The whole is the relationship between its parts

An object such as an apple is the relationship between its parts

The parts of an an apple have a physical existence in the world.

The question is, does the whole, the object, the apple, have an ontological existence in the world.

Do relations ontologically exist in the world

As regards the world independent of any observer, if relations don't have an ontological existence, then objects such as apples, which are relations between its parts, cannot ontologically exist in the world.

If relations do have an ontological existence, then objects such as apples, which are relations between its parts, can ontologically exist in the world.

FH Bradley argued against the existence of external relations in his regress argument, whereby either a relation R is nothing to the things a and b it relates, in which case it cannot relate them, or, it is something to them, in which case R must be related to them.

I personally don't believe relations exist ontologically in the world for two reasons

Reason one. When looking at two parts A and B, there is no information within Part A as to the existence of Part B, there is no information within Part B as to the existence of Part A, and there is no information within the space between A and B as to the existence of either A and B located at its ends.

Reason two. If ontological relations exist in the world, then there must be ontological relations between all parts in the world, not just some of them. For example, there must be an ontological relation between my pen and the Eiffel Tower, between an apple in France and an orange in Spain, between a particular atom in the Empire State Building and a particular atom in the Taj Mahal - none of which makes sense.

Do relations ontologically exist in the mind

As regards the mind of the observer, I know that I am conscious. I know that I have a unity of consciousness, in that what I perceive is a a single experience

John Raymond Smythies described the binding problem as "How is the representation of information built up in the neural networks that there is one single object 'out there' and not a mere collection of separate shapes, colours and movements?

I can only conclude, from my personal experience, that relations do have an ontological existence in my mind, such that when I perceive an apple, I perceive the whole apple and not just a set of disparate parts

Modern Realism

I believe that parts in the world have a physical existence independent of any mind.

As I don't believe that relations have a physical existence in the world, then no object, such as an apple, a table, a chair, etc, can have a physical existence in the world.

Scholastic Realism

I can only believe that both parts and relations do have an ontological existence in the mind, meaning that objects, such as apples, tables, chairs, etc do have an ontological existence in my mind.

The word "object" has two distinct meanings

Confusion arises in language as the two distinct meanings of "object" are generally not differentiated.

There is the "object" in my mind and the "object" in the world

The consequence is that when I perceive an object such as an apple, the apple I am thinking about exists in my mind but not in the world.

It would be wrong to say that the "apple" is an illusion, as the "apple" does exist, but in my mind rather than the world.

Conclusion

Objects such as apples ontologically exist in my mind but not in the world.

When I perceive an apple, I am perceiving something that is real, just that it is in my mind rather than the world

That relations do exist in the mind, allowing me a unity of consciousness is an absolute mystery to me, although a fact.

However, even the fact that relations exist in my mind neither supports nor opposes the question of dualism. Relations may exist in the mind whether the mind is separate substance to the brain or the mind is an expression of the brain -

Olivier5

6.2kWhat are objects

Olivier5

6.2kWhat are objects

The whole is the relationship between its parts

An object such as an apple is the relationship between its parts

The parts of an an apple have a physical existence in the world.

The question is, does the whole, the object, the apple, have an ontological existence in the world. — RussellA

Note that the parts of an apple, eg its flesh, its seed or its skin, are themselves made of smaller parts (cells) themselves made of smaller parts (biochemical structures) etc. etc. It's the same dialectic of wholes and their parts all the way down. So if apples do not exist on account of being wholes, nothing exists.

Therefore, relations objectively exist in this world.

For example, there must be an ontological relation between my pen and the Eiffel Tower, between an apple in France and an orange in Spain, between a particular atom in the Empire State Building and a particular atom in the Taj Mahal - none of which makes sense. — RussellA

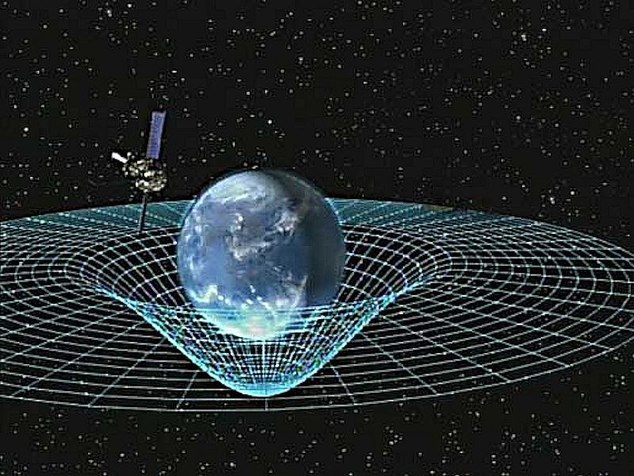

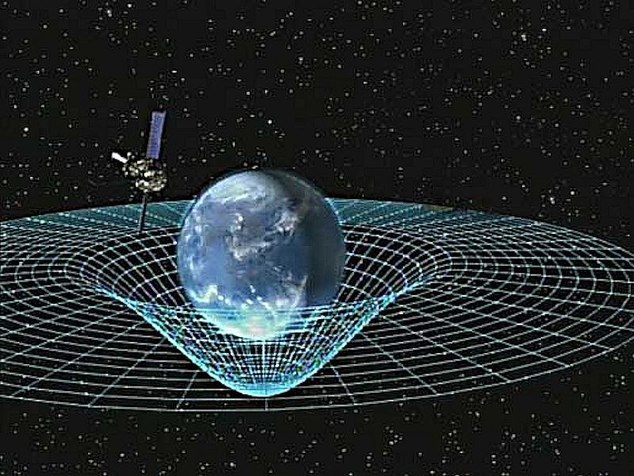

It makes perfect sense. In Newtonian physics, an atom in the Taj Mahal must by necessity attract an atom in the Empire State Building, though the resulting force is I guess extremely small. In General Relativity, everything is relative -- relative to everything else I would think. -

Olivier5

6.2kLaws exist and these will be broken/violated if nonphysical minds interact, causally, with physical systems. — Agent Smith

Olivier5

6.2kLaws exist and these will be broken/violated if nonphysical minds interact, causally, with physical systems. — Agent Smith

What substance are your laws made of? -

Wayfarer

26.1kObjects such as apples ontologically exist in my mind but not in the world. — RussellA

Wayfarer

26.1kObjects such as apples ontologically exist in my mind but not in the world. — RussellA

You're using the term 'ontologically' to denote 'really existent', your implication being that physical things are truly existent whilst relations etc exist 'in the mind'. But the division between 'in my mind' and 'in the world' is not so clear cut, as the division is also in your mind! A being is aware of itself in the world, but that 'awareness of self in the world' is also the activity of consciousness.

Your posts are written from the perspective of uncritical realism, starting with the assumption that the sensory domain possesses inherent and unquestionable reality, when in fact that is what is at issue in philosophy.

What could it mean to "see things as they really are"? Are you not making an unwarranted assumption that things "really are some ultimate way". Why should that be necessary? — Janus

Because that is what the subject of philosophy is concerned with. That is the basis of the idea of 'appearance and reality' which is the fundamental preoccupation of philosophy since the subject began. -

Janus

18kBecause that is what the subject of philosophy is concerned with. That is the basis of the idea of 'appearance and reality' which is the fundamental preoccupation of philosophy since the subject began. — Wayfarer

Janus

18kBecause that is what the subject of philosophy is concerned with. That is the basis of the idea of 'appearance and reality' which is the fundamental preoccupation of philosophy since the subject began. — Wayfarer

Maybe so with ancient and medieval philosophy, but in today's terms a very narrow, anachronistic conception of philosophy, corrected by Kant 240 years ago. Phenomenology has nothing to do with ultimate concerns. Neither has continental or analytic philosophy or pragmatism. You're living in the past. -

RussellA

2.6kSo if apples do not exist on account of being wholes, nothing exists — Olivier5

RussellA

2.6kSo if apples do not exist on account of being wholes, nothing exists — Olivier5

I agree that the parts of what we think of as an apple do physically exist in the world.

But the parts will still physically exist whether or not relations have an ontological existence in the world.

Therefore, the existence of the parts neither proves nor disproves the existence of relations.

In Newtonian physics, an atom in the Taj Mahal must by necessity attract an atom in the Empire State Building, — Olivier5

Considering atom A in the Empire State Building and atom B in the Taj Mahal

I agree atom A may experience a force from atom B, and vice versa.

Atom A may experience a force from atom B, but there is no information within the force that relates atom A to atom B.

Similarly, atom B may experience a force from atom A, but there is no information within the force that relates atom B to atom A.

There is also no information within the space between atoms A and B that relates atoms A to B

If an ontological relation does exist in the world between atom A and atom B, the question is, where is the information that there is such a relation. -

RussellA

2.6kYour posts are written from the perspective of uncritical realism, starting with the assumption that the sensory domain possesses inherent and unquestionable reality, when in fact that is what is at issue in philosophy. — Wayfarer

RussellA

2.6kYour posts are written from the perspective of uncritical realism, starting with the assumption that the sensory domain possesses inherent and unquestionable reality, when in fact that is what is at issue in philosophy. — Wayfarer

Don't think I agree.

A physical world exists independently of us

I agree with Critical Realism in a belief in Ontological Realism, that a physical reality exists and operates independently of our awareness, knowledge, or perception of it.

Our knowledge is both a priori and a posteriori

I believe that we have knowledge of the world both a priori and a posteriori.

A priori knowledge is innate knowledge - of space, time, causation, colour, etc - that has been genetically built into the brain after millions of years of evolution.

A posteriori knowledge we gain through our senses.

Indirect Realism explains more than Direct Realism

I agree with both Direct and Indirect Realism that there is a correspondence between events in the world and how we perceive these events in our minds, even though in Direct Realism the correspondence is direct whilst in Indirect Realism the correspondence is indirect.

Because I believe that relations don't ontologically exist in the world, but do exist in the mind, and as Direct Realism is the claim that our senses provide us with direct awareness of the external world, then I don't believe in Direct Realism.

As regards Indirect Realism, taking an example, because an object emits a wavelength of 700nm, and yet we perceive it as the colour red, our perception of the colour red can only be a representation of the wavelength of 700nm, pointing to Indirect Realism as the true explanation. Accepting Indirect Realism as a true explanation, we can never know what is on the other side of our senses, we can never know the true nature of reality.

Trying to understand what is on the other side of our senses

I agree that when we perceive, we are directly perceiving our senses and not what is on the other side of them. Yet, because I also believe in the Law of Causation. I believe that what I perceive in my senses is an effect of a prior cause, and that prior cause is a world independent of me as an observer.

Each moment in time is a different reality. What I perceive in my senses is real, what caused these sensations in the world is real, going back in time through successive cause and effect to some time in the beginning.

I agree with Critical Realism

I agree with empiricism that the the only way to gain knowledge is what we sense through the senses, making the note that our a priori knowledge originally came through the senses.

I agree with positivism that only knowledge supported by facts is valid.

But I also agree with Critical Realism that knowledge is not gained by a simplistic conjunction between cause and effect, but rather is an ongoing process whereby we gradually and incrementally improve our concepts in trying to make sense of a complex world that exists independently of us.

Make sense, not in the sense of understanding the nature of absolute reality, but make sense sufficiently for us to pragmatically survive in the environment that we find ourselves in. -

Wayfarer

26.1kYour posts are written from the perspective of uncritical realism, — Wayfarer

Wayfarer

26.1kYour posts are written from the perspective of uncritical realism, — Wayfarer

Don't think I agree.

A physical world exists independently of us

I agree with Critical Realism in a belief in Ontological Realism, that a physical reality exists and operates independently of our awareness, knowledge, or perception of it. — RussellA

Here is a definition of critical realism:

Critical Realism (CR) is a branch of philosophy that distinguishes between the real and the observable. The real can not be observed and exists independent from human perceptions, theories, and constructions. The world as we know and understand it is constructed from our perspectives and experiences, through what is observable. Thus, according to critical realists, unobservable structures cause observable events and the social world can be understood only if people understand the structures that generate events.

Notice that this doesn't declare that the real world is physical. What we understand as physical is a matter of definition and is constantly changing. There is no simple definition of matter and matter itself cannot be shown to possess intrinsic reality.

I agree that a priori knowledge is innate, but don't agree that it can be explained in terms of natural selection and genetics on the grounds that that is reductionist. Again that is a naturalist assumption.

I believe that what I perceive in my senses is an effect of a prior cause, and that prior cause is a world independent of me as an observer. — RussellA

That is 'transcendental realism', the commonsense pre-theoretic view that objects in space and time are things in themselves or possess an innate reality independently of the mind.

What you're not seeing is the mind's contribution to everything asserted about the mind-independent world.

I think you're describing a scientific realist attitude. Scientific realism assumes that the world explored by science exists independently of us and our knowledge of it. I think that is a sound methodological starting point. But it is *not* a metaphysic. It starts with the assumption that the 'external' world is real, not seeing that 'external' is itself a representation. Naturalism looks at the phenomenon of life from an external viewpoint, the fossil record, evolution, and so on, but life as it is lived occurs from a first-person perspective. Naturalism subordinates the first- to the third-person p.o.v., as if the third-person approach is privileged and the authoritative source of judgement. But again it fails to appreciate the sense in which even the sciences are human constructs - which is not to deprecate science, but to demote it from the assumed role as 'arbiter of reality'. As we're not ultimately apart from or outside of the world or reality as such, the naturalist assumption of our separateness and the presumed objective reality of natural phenomena has no ultimate validity. It's simply a working assumption, not an ultimate truth. This is the key insight of non-dualist philosophy. -

Janus

18kI believe that what I perceive in my senses is an effect of a prior cause, and that prior cause is a world independent of me as an observer. — RussellA

Janus

18kI believe that what I perceive in my senses is an effect of a prior cause, and that prior cause is a world independent of me as an observer. — RussellA

That is 'transcendental realism', the commonsense pre-theoretic view that objects in space and time are things in themselves or possess an innate reality independently of the mind. — Wayfarer

So, you believe that if you as an observer ceased to exist, the world would go with you? -

javra

3.2kSo, you believe that if you as an observer ceased to exist, the world would go with you? — Janus

javra

3.2kSo, you believe that if you as an observer ceased to exist, the world would go with you? — Janus

Picking up on this: Its utterly reasonable to me to claim that when the unique self which I am will cease existing, all my personal loves and idiosyncratic perspectives will end with me - but not yours or those of the eight billion and counting, to not mention the far greater quantity of unique selves of lesser sentient beings.

What I find to be a more interesting question in respect to the thread: If all awareness in the cosmos were to somehow miraculously vanish - from that of the lowly bacteria to us, to that occurring in any other place in the universe irrespective of its degree of development; even that applicable to panpsychism if one so maintains the world to be - what, if anything, would remain of the world as we in any way know it?

While I take this to be an open-ended issue, I can’t fathom any type of envisioned world occurring in the absence of any awareness to envision it.

(As to the issue of life evolving out of nonlife, some as of yet nebulous system of panpsychism could potentially account for this just as well as, if not better then, the metaphysical stance of physicalism does. But, here, the world would be primordially constituted of awareness, thereby entailing that no world occurs if no awareness occurs.) -

Wayfarer

26.1kIf all awareness in the cosmos were to somehow miraculously vanish - from that of the lowly bacteria to us, to that occurring in any other place in the universe irrespective of its degree of development; even that applicable to panpsychism if one so maintains the world to be - what, if anything, would remain of the world as we in any way know it? — javra

Wayfarer

26.1kIf all awareness in the cosmos were to somehow miraculously vanish - from that of the lowly bacteria to us, to that occurring in any other place in the universe irrespective of its degree of development; even that applicable to panpsychism if one so maintains the world to be - what, if anything, would remain of the world as we in any way know it? — javra

I've addressed this a number of times with reference to a passage in Brian Magee's book on Schopenhauer, which can be read here, here, here and here.

The empiricist view is that the universe exists irrespective of whether it is observed or not. In one sense that is true, but the empiricist overlooks the role of the observing mind in the representation of the Universe and so what it means to say the universe exists.

There are two key passages in the Critique of Pure Reason that address this:

I understand by the transcendental idealism of all appearances the doctrine that they are all together to be regarded as mere representations and not things in themselves, and accordingly that space and time are only sensible forms of our intuition, but not determinations given for themselves or conditions of objects as things in themselves. To this idealism is opposedtranscendental realism, which regards space and time as something given in themselves (independent of our sensiblity). The transcendental realist therefore represents outer appearances (if their reality is conceded) as things in themselves, which would exist independently of us and our sensibility and thus would also be outside us according to pure concepts of the understanding. (CPR, A369)

Having carefully distinguished between transcendental idealism and transcendental realism, Kant then goes on to introduce the concept of empirical realism:

The transcendental idealist, on the contrary, can be an empirical realist, hence, as he is called, a dualist, i.e., he can concede the existence of matter without going beyond mere self-consciousness and assuming something more than the certainty of representations in me, hence the cogito ergo sum. For because he allows this matter and even its inner possibility to be valid only for appearance– which, separated from our sensibility, is nothing –matter for him is only a species of representations (intuition), which are call external, not as if they related to objects that are external in themselves but because they relate perceptions to space, where all things are external to one another, but that space itself is in us. (A370)

Again, you're picturing 'a world in which there are no mind' - the early earth, drifting silently through the empty void. But that is still a concept, an idea, ordered according to the intuitions of space and time. The point about realism - whether scientific or naive - is that it supplies that human perspective, situates the concept in a temporal and spatial matrix - and then doesn't realise it is doing so. Whatever we say about 'reality' assumes a perspective, but then forgets that it is actually supplying the perspective. It is analogous to wearing a pair of spectacles, without which nothing can be seen, and then looking through them, and demanding 'show me where in this picture there are spectacles'. — Wayfarer -

javra

3.2kIf we believe the science it tells us that the universe did indeed exist before any organisms appeared on the scene. — Janus

javra

3.2kIf we believe the science it tells us that the universe did indeed exist before any organisms appeared on the scene. — Janus

I believe I've already accounted for this in my post via some, as of yet to be clarified, form of panpsychism.

I do see where you're coming from. My own view has nowadays come to take the primacy of awareness nearly for granted. However, due to my own views - liken them maybe to those of a logos operated anima mundi when it comes to the physical world we all share - this does entail that what we discover of the anima mundi (else, what the anima mundi informs us of) is, for lack of a better wording, our closest proximity to an absolute objective truth. A view easily shunned in multiple ways, I'm sure, but in this view, fully granting the primacy of awareness, we are being informed by the world that we sapient beings evolved from beings of lesser sentience which themselves somehow evolved out of nonlife. My degree of understanding may not be good enough to understand how, yet due to the very premises I hold - including that of awareness's primacy - I cannot find myself denying the data that life evolved out of nonlife. If not on our planet then in the cosmos at large.

In parallel to the issue of whether the Sun rises or else the Earth's axis spins, I personally find that on one hand life's evolution form nonlife really doesn't much matter in the context of the lives we live. On the other hand, I do believe its were deeper truths about the world in large, together with those pertaining to our own being, are to be uncovered.

But yes, regardless of any differences we might have, at the end of the day I do agree with this:The empiricist view is that the universe exists irrespective of whether it is observed or not. In one sense that is true, but the empiricist overlooks the role of the observing mind in the representation of the Universe and so what it means to say the universe exists. — Wayfarer -

Janus

18kI believe I've already accounted for this in my post via some, as of yet to be clarified, form of panpsychism. — javra

Janus

18kI believe I've already accounted for this in my post via some, as of yet to be clarified, form of panpsychism. — javra

OK, but I can't see how pan-psychism would help. I see no reason to think it is impossible for physical things like planets and stars to exist absent humans or other percipients. I see the so-called "hard problem" as existing only on account of a presumptuous idea that we understand the nature of physical matter.

You say you agree with "the empiricist view is that the universe exists irrespective of whether it is observed or not. In one sense that is true, but the empiricist overlooks the role of the observing mind in the representation of the Universe and so what it means to say the universe exists".

It is. I think, trivially true that we and all percipients contribute to how things are perceived on account of different perceptual constitutions. That aside, what it means to say things exist independently of percipients, is that they are there to be perceived, and there regardless of whether or not they are perceived. -

javra

3.2kRegardless of that, what it means to say things exist independently of percipients, is that they are there to be perceived, and there regardless of whether or not they are perceived. — Janus

javra

3.2kRegardless of that, what it means to say things exist independently of percipients, is that they are there to be perceived, and there regardless of whether or not they are perceived. — Janus

Right. Of course. Independently of me, or of you, or of any other individual sentience. But would they in any way occur in the complete absence of any and all awareness?

As an analogy, one single geometric point is indefinite, volumeless, and in this sense nonexistent. There must be two or more geometric points to establish any kind of space whatsoever - a space which the two or more geometric points inhabit with location. Now, given that space already is, this entails that a plurality of geometric points occurs. Take any one geometric point away and the given space yet remains due to there yet occurring two or more geometric points to define it. So, relative to individual geometric points, the space they occupy occurs independently of them. Yet, relative to all geometric points, the occurrence of the space they occupy will be dependent on the geometric points' primacy of being.

In like enough manner, the physical world (to not even mention individual objects in it) occurs fully independently of me, or you, of any other individual psyche. But in the absence of all awareness, including that pertaining to psyches, there would be no such thing as a world.

Like an ocean that is made up of water drops. The ocean is in one way fully independent of the individual water drops it consist of: taking a buck of water away makes no difference. Yet, there would be no ocean in the complete absence of all water drops.

This not with an intention to convince but to explain. I agree that the physical world is mind-independent (or indifferent) when addressing individual minds or individual mind cohorts. But I uphold that it is mind-dependent (or at least awareness-dependent) when addressing the occurrence of all coexisting instantiations of awareness.

Its an alternative view to yours - but it does account for why the moon is irrespective of whether I, or you, or some lesser animal somewhere, happens to be mindful of it or not. For one thing, the moon is thoroughly enmeshed in a cosmic causal matrix, the same we're all embedded in, and will thus remain long after we no longer are in this world.

Edit: Panpsychism of some form would then need to be to account for a life-devoid cosmos from which life evolved, this within such a system pivoting on a primacy of awareness. -

Janus

18kIn like enough manner, the physical world (to not even mention individual object in it) occurs fully independently of me, or you, of any other individual psyche. But in the absence of all awareness, including that pertaining to psyches, there would be no such thing as a world. — javra

Janus

18kIn like enough manner, the physical world (to not even mention individual object in it) occurs fully independently of me, or you, of any other individual psyche. But in the absence of all awareness, including that pertaining to psyches, there would be no such thing as a world. — javra

If the physical world occurs independently of any and all individual psyches, then why would there be no such thing as a world in the absence of all awareness? Are you positing a collective psyche or something like that? -

javra

3.2kAre you positing a collective psyche or something like that? — Janus

javra

3.2kAre you positing a collective psyche or something like that? — Janus

As the "creator of the world" you mean? No. Tried to simplistically illustrate what I'm positing via the analogy to geometric points. More concretely, yet still simplistically, replace "geometric points" with "first-person points of view (conscious or otherwise)" and "geometric space" with "physical space". Lots of details to go through for which this forum isn't ideally suited. But the conclusion: physical space is a necessary correlate of there co-occuring two or more first-person points of view - and occurs independently of what these might individually or collectively desire in regard to space's existence. Just as there would be no geometric space in the absence of two or more geometric points, so too would there be no physical space in the absence of two or more instantiations of awareness. As physical space is contingent on there being two or more instantiations of awareness, so too will the physical world in totality of complexity be. But I really don't want to drag this into "my views". In short, though, the answer to the question you posed is "no": there is no creator psyche of the world from where I stand.

In fairness, though, you have so far not directly answered the question I've posed:

If all awareness in the cosmos were to somehow miraculously vanish [...] what, if anything, would remain of the world as we in any way know it? — javra -

RussellA

2.6kPhysicalism

RussellA

2.6kPhysicalism

What we understand as physical is a matter of definition and is constantly changing — Wayfarer

Yes. Physicalism is sometimes known as ‘materialism’. Materialists historically held that everything was matter. But physics itself has shown that not everything is matter in this sense. For example, forces such as gravity are physical but it is not clear that they are material in the traditional sense Physicalists don’t deny that the world might contain many items that at first glance don’t seem physical, such as biological, psychological, moral, social or mathematical, but at the end of the day, such things either are or are founded on the physical.

The importance of the Law of Causation

the mind's contribution to everything asserted about the mind-independent world. — Wayfarer

I agree with the quote, as my position is that of Indirect Realism (our conscious experience is not of the real world itself but of an internal representation of the real world) rather than Direct Realism (our senses provide us with direct awareness of the external world, and the world derived from our sense perception should be taken at face value).

My immediate perception is of the sensations through my senses, not what caused these sensations. I perceive sensations through my senses - the colour red, a sharp pain, a bitter taste, an acrid smell, a screeching noise. The question is, how much can we discover about the reality of the external world just using these sensations through our senses

The only key we have to discover what is on the other side of our senses is the Law of Causation. As I believe in the Law of Causation intellectually and know the Law of Causation instinctively, being a priori innate, I both believe and know that there is an external world causing these sensations.

Critical Realism, RW Sellars and causation

Critical realism follows from RW Sellars and Critical Realism (1916). Sellars argued against Idealism, and proposed real substances (as opposed to ideas, universals, etc) as objects of perception. Sellars held that the normal objects of perception are real full-bodied independent substances, rejecting “the historical desiccation of the category of substance,” that is, the whittling down of the Ancient and Medieval robust notion of substance to Locke’s “I know not what”.

Critical Realism, Roy Bhaskar and causation

Roy Bhaskar is known as initiating Critical Realism, including A Realist Theory of Science (1975). He held the position that unobservable structures cause observable events, which supported the ontological reality of causal powers independent of their empirical effects. It follows that what scientists are learning about, therefore, cannot be causal laws, understood as invariant patterns of events, rather they are learning about causal mechanisms, tendencies that tend to bring about certain types of outcome, but do not always do so. Objects are able to exert causal powers, but only within a complex structure.

Summary

To say the world is physical within Physicalism encompasses many things, and includes both matter and forces.

We can only discover what is on the other side of our senses using the Law of Causation. If our sensations such as pain had no cause and happened spontaneously, the world we live in would be a very unpredictable place.

The earlier Sellars Critical Realism required a world of real, full-bodied independent substances.

The later Bhaskar Critical Realism argued for objects in the world having causal powers.

IE, the Law of Causation is key in being able to discover what is not directly observable.

Welcome to The Philosophy Forum!

Get involved in philosophical discussions about knowledge, truth, language, consciousness, science, politics, religion, logic and mathematics, art, history, and lots more. No ads, no clutter, and very little agreement — just fascinating conversations.

Categories

- Guest category

- Phil. Writing Challenge - June 2025

- The Lounge

- General Philosophy

- Metaphysics & Epistemology

- Philosophy of Mind

- Ethics

- Political Philosophy

- Philosophy of Art

- Logic & Philosophy of Mathematics

- Philosophy of Religion

- Philosophy of Science

- Philosophy of Language

- Interesting Stuff

- Politics and Current Affairs

- Humanities and Social Sciences

- Science and Technology

- Non-English Discussion

- German Discussion

- Spanish Discussion

- Learning Centre

- Resources

- Books and Papers

- Reading groups

- Questions

- Guest Speakers

- David Pearce

- Massimo Pigliucci

- Debates

- Debate Proposals

- Debate Discussion

- Feedback

- Article submissions

- About TPF

- Help

More Discussions

- Other sites we like

- Social media

- Terms of Service

- Sign In

- Created with PlushForums

- © 2026 The Philosophy Forum