-

Wayfarer

26.1kThe semantic only has reality insofar as it is embodied in neurophysiological matter or its correlates in the material world. — Enrique

Wayfarer

26.1kThe semantic only has reality insofar as it is embodied in neurophysiological matter or its correlates in the material world. — Enrique

Says which science? What about mathematicians and pure maths? How and in what is that embodied, or even 'correlated'? And with what? Sure, mathematicians are embodied beings, as are we all, but the ability to explore mathematics is not a given on the grounds of merely being embodied. There are maths prodigies and geniuses that solve real problems that have eluded others for centuries. In what are such problems embodied? To say that they only exist in brains, then they're just the product of brains, and have no intrinsic reality, which is a bold claim, and one that not many mathematicians would agree with, I would think.

Claiming that a substance is "immaterial" seems contradictory to me. — Enrique

I understand that, but be aware of the meaning of 'substance' in philosophy. In normal use, 'substance' means 'a material with uniform properties'. So an 'immaterial substance', using the word in that sense, is 'immaterial material' which is indeed self-contradictory. Substance in philosophy has a different meaning, 'the bearer of attributes'. It is nearer in meaning to 'being' or 'subject' than to what 'substance' means in normal speech.

But that is not the substance of my argument. What I would like to say is that such basic elements of reason as 'is equal to', 'is the same as', or even simply 'is', have no physical equivalent. They are in no sense physical. They are purely intellectual in nature, arising from the ability to name, abstract and compare, and are completely ideational. Sure, you can't perform those functions without a brain, but that doesn't mean that you can reduce those abilities to 'brain functions' as if that means anything more than wishful thinking (or one of Popper's 'promisory notes of materialism').

I think you've bought into a popular myth, which is that brain produces mind, one of the prevailing myths of today. From a common-sense point of view, it seems obvious but I don't think it is at all established, as the nature of the mind remains an elusive question, and not strictly a scientific question.

There's quite a famous book, The Philosophical Foundations of Neuroscience, by Bennett and Hacker, a neuroscientist and philosopher. I haven't read all of it, but from what I have read, it's witheringly critical of the idea that 'the brain' does this or that - or does anything, by itself. That is said to be the 'mereological fallacy', that is, the ascription to a part of what is really the activity of the whole being. In short, brains don't do anything - human beings do things, and obviously need a functioning brain to do anything whatever, but the brain is embodied, encultured, part of a whole ('mereology' is the study of the relations of parts and wholes.)

In their review of John Searle, Bennett and Hacker find much with which they agree. Cartesian dualism, behaviorism, identity theory, eliminative materialism and functionalism are all rejected, and rightly so. Searle advocates “biological naturalism,” the view that consciousness is a biological phenomenon, a proper subject of the biological sciences (p. 444). Bennett and Hacker serve up no objection here. It is when Searle claims that “mental phenomena are caused by neurophysiological processes in the brain and are themselves features of the brain” (Searle, Rediscovery, p. 1) that Bennett and Hacker demur. Searle's claim commits the mereological fallacy discussed earlier. Brains are no more conscious than they are capable of taking a walk or holding a conversation. True, no animal could do either of these things without a properly functioning brain. But it is the person, not the brain, that engages in these activities.

unless you mean something along the lines of the morphic fields that were mentioned by Janus, — Enrique

Actually it was me that brought those up, as a way to explain past-life memories, although that topic is a guaranteed thread derailer. -

Mww

5.4kdo we begin with that which is given to us, or do we begin with that which is in us, that it is given to.

Mww

5.4kdo we begin with that which is given to us, or do we begin with that which is in us, that it is given to.

— Mww

I tend to think that what is in us is given to us as much as what is external. — Janus

Yes, agreed, at first glance. We all are given the same kind of brain, all brains work the same way, reason manifests as brain function, therefore we all reason the same way. Nevertheless, while Nature may have seen fit to equip all of us equally, she has not seen fit to cause the manifestations of its use, to be equal across its capacity in each of us.

————-

My point was that we can arrange them in all the ways necessary such as to show the attributes that go to define the quantity six. — Janus

I don’t understand how merely arranging six objects in various ways shows the attributes that defines the quantity “six”. Arranged as a four-sided figure, arranged as a pyramid, arranged with each other as a succession of points.....there’s still just a quantity of objects represented by some number. A quantity can be conceived a priori as a mere succession of aggregates, a particular number just indicates a place in such succession. No need to arrange anything.

And we couldn’t even conceive succession without antecedent relation, so....that takes care of that.

All in good fun. -

Enrique

845There are maths prodigies and geniuses that solve real problems that have eluded others for centuries. In what are such problems embodied? To say that they only exist in brains, then they're just the product of brains, and have no intrinsic reality, which is a bold claim, and one that not many mathematicians would agree with, I would think. — Wayfarer

Enrique

845There are maths prodigies and geniuses that solve real problems that have eluded others for centuries. In what are such problems embodied? To say that they only exist in brains, then they're just the product of brains, and have no intrinsic reality, which is a bold claim, and one that not many mathematicians would agree with, I would think. — Wayfarer

Kind of a tangent, but has implications for ideal Platonic form and seems to be talked about a lot at this forum, so maybe it's worth thinking about. This will probably resolve some uncertainty for me.

My argument is that ideal geometrical objects are the equivalent of a space unicorn, which seems to be the convenient fiction perspective you mentioned. Any object ever instantiated has imperfectly aligned angles, no matter how slight, is not quite symmetrical in some way, and has unevenly textured boundaries. An ideal object is like cobbling together perfect alignment, symmetry and smoothness in the mind's eye, features inherent in whole numbers as specs that are self-contained with artificially simple exactness, and then labeling a material figure such that ideal properties are assumed present in the real world when they actually are not and never have been.

The mind conceives of the mathematical unicorn by imagining a figure with no imprecisions (neurophysiology), and represents the imaginary concept in a real figure by more or less disregarding the imprecisions intrinsic to instantiation (physical matter). No hyperspace realm where objects with ideal geometry float around waiting to be discovered has ever been empirically proven to exist, exactly in the same way that a real unicorn has never been witnessed. Ideal objects are only present in consciousness, and so would not exist without particular types of cognition.

It is the radical precision of ideal geometry as concept that makes it such a powerful tool, not its actual embodiment as substance, and so can be expected to evolve multiple ways by convergent evolution in similarity to bilateral symmetry etc. But like any purely conceptual (and thus conscious) schema, ideal geometry has to be reducible to neurophysiology, or if not this, then matter of some kind. Postulating a domain where possibilities actually exist or where anything actually exists demands support from a theory of matter to be legitimate, a corresponding and coherent model of instantiated substance, as does any epistemic claim. Quibbling about the meaning of "to be" doesn't seem like it gets at the truth, anymore at least, but I admit I'm not knowledgeable about the relevant Aristotelian arguments.

Explain to me why this reasoning doesn't compel those who are not being disingenuous or merely equivocating about the definitions of verbiage. -

Janus

18kAkashic fields, or morphic fields. It's a no-go topic here, but suffice to say it stymies standard-issue physicalism. — Wayfarer

Janus

18kAkashic fields, or morphic fields. It's a no-go topic here, but suffice to say it stymies standard-issue physicalism. — Wayfarer

Sure, it might be rejected by "standard issue" physicalists, but it's an alternative explanation to positing that consciousness survives the death of the body, and it is not incompatible with physicalism, per se. -

Janus

18kI don’t understand how merely arranging six objects in various ways shows the attributes that defines the quantity “six”. Arranged as a four-sided figure, arranged as a pyramid, arranged with each other as a succession of points.....there’s still just a quantity of objects represented by some number. — Mww

Janus

18kI don’t understand how merely arranging six objects in various ways shows the attributes that defines the quantity “six”. Arranged as a four-sided figure, arranged as a pyramid, arranged with each other as a succession of points.....there’s still just a quantity of objects represented by some number. — Mww

I perhaps didn't explain it very well. What I meant was to take six objects and separate them into groups. So you separate them into groups of two and it becomes immediately obvious that you get three groups of two, with nothing left out. Or you can do two groups of three. So the qualities of divisibility of six objects is immediately perceptually apparent. Try it with seven objects and it becomes apparent that it can only be divided into seven "groups " of one. any other combination will leave a remainder. -

Wayfarer

26.1kThe mind conceives of the mathematical unicorn by imagining a figure with no imprecisions (neurophysiology), and represents the imaginary concept in a real figure by more or less disregarding the imprecisions intrinsic to instantiation (physical matter). — Enrique

Wayfarer

26.1kThe mind conceives of the mathematical unicorn by imagining a figure with no imprecisions (neurophysiology), and represents the imaginary concept in a real figure by more or less disregarding the imprecisions intrinsic to instantiation (physical matter). — Enrique

Notice how you've begged the question here by inserting 'neurophysiology' as if this is a premise rather than a conclusion. And again, mental images can't be meaningfully understood in terms of neurophysiology. There are no shapes or images to be found in neural matter.

But the main point is that conceiving and imagining are different faculties. I've cribbed a blog post from Edward Feser here because it explains the difference very succinctly:

As Aristotelians and Thomists use the term, intellect is that faculty by which we grasp abstract concepts (like the concepts man and mortal), put them together into judgments (like the judgment that all men are mortal), and reason logically from one judgment to another (as when we reason from all men are mortal and Socrates is a man to the conclusion thatSocrates is mortal). It is to be distinguished from imagination, the faculty by which we form mental images (such as a visual mental image of what your mother looks like, an auditory mental image of what your favorite song sounds like, a gustatory mental image of what pizza tastes like, and so forth); and from sensation, the faculty by which we perceive the goings on in the external material world and the internal world of the body (such as a visual experience of the computer in front of you, the auditory experience of the cars passing by on the street outside your window, the awareness you have of the position of your legs, etc.).

That intellectual activity -- thought in the strictest sense of the term -- is irreducible to sensation and imagination is a thesis that unites Platonists, Aristotelians, and rationalists of either the ancient Parmenidean sort or the modern Cartesian sort. The thesis is either explicitly or implicitly denied by modern empiricists and by ancients like Democritus; as I noted in an earlier post, the various bizarre metaphysical conclusions defended by writers like Berkeley and Hume largely rest on the conflation of intellect and imagination. But the irreducibility of intellect to imagination is for all that undeniable, for several reasons.

Thinking versus imagining

First, the concepts that are the constituents of intellectual activity are universal while mental images and sensations are always essentially particular. Any mental image I can form of a man is always going to be of a man of a particular sort -- tall, short, fat, thin, blonde, redheaded, bald, or what have you. It will fit at most many men, but not all. But my concept man applies to every single man without exception. Or to use my stock example, any mental image I can form of a triangle will be an image of an isosceles , scalene, or equilateral triangle, of a black, blue, or green triangle, etc. But the abstract concept triangularity applies to all triangles without exception. And so forth.

Second, mental images are always to some extent vague or indeterminate, while concepts are at least often precise and determinate. To use Descartes’ famous example, a mental image of a chiliagon (a 1,000-sided figure) cannot be clearly distinguished from a mental image of a 1,002-sided figure, or even from a mental image of a circle. But the concept of a chiliagon is clearly distinct from the concept of a 1,002-sided figure or the concept of a circle. I cannot clearly differentiate a mental image of a crowd of one million people from a mental image of a crowd of 900,000 people. But the intellect easily understands the difference between the concept of a crowd of one million people and the concept of a crowd of 900,000 people. And so on.

Third, we have many concepts that are so abstract that they do not have even the loose sort of connection with mental imagery that concepts like man, triangle, and crowd have. You cannot visualize triangularity or humanness per se, but you can at least visualize a particular triangle or a particular human being. But we also have concepts -- such as the concepts 'law', 'square root', 'logical consistency', 'collapse of the wave function', and innumerably many others -- that can strictly be associated with no mental image at all. You might form a visual or auditory image of the English word 'law' when you think about law, but the concept 'law' obviously has no essential connection whatsoever with that word, since ancient Greeks, Chinese, and Indians had the concept without using that specific word to name it. — Ed Feser - Think, McFly, Think

Quibbling about the meaning of "to be" doesn't seem like it gets at the truth, — Enrique

You don't think the meaning of being is fundamental to philosophy? Do you think what you're writing is philosophy? -

Enrique

845

Enrique

845

I tend to think the reasoning of math combines all three categories: intellect, imagination and sensation (as does any process of reasoning?). The interesting inquiry from my angle (thinking a lot about panprotopsychist consciousness theory via quantum biology) is how these faculties and their subject matter are situated in relationship to the brain.

It seems that the way thinking becomes stereotyped means intellect is closely entwined with the types of patterns characteristic of material structure, not a domain adequately explained as abstraction to the core, but what kind of matter this will turn out to be is perhaps uncertain. -

Wayfarer

26.1kThe interesting inquiry from my angle (thinking a lot about panprotopsychist consciousness theory via quantum biology) is how these faculties and their subject matter are situated in relationship to the brain. — Enrique

Wayfarer

26.1kThe interesting inquiry from my angle (thinking a lot about panprotopsychist consciousness theory via quantum biology) is how these faculties and their subject matter are situated in relationship to the brain. — Enrique

I don't get that. It's not necessary to map everything against the brain, as if that amounts to an explanation. The neurosciences are vital sciences but I can't see the need to do that. -

Mww

5.4kSo the qualities of divisibility of six objects is immediately perceptually apparent. — Janus

Mww

5.4kSo the qualities of divisibility of six objects is immediately perceptually apparent. — Janus

I suppose. From a further metaphysical reduction, however, any quantity that has been assembled can be disassembled. So the divisibility of some quantity of objects is only immediately perceivable iff an aggregate of them has already been assembled.

But as long as I’m speaking number, and you’re speaking number of objects, we’re passing in the dark. I have no problem with the claim that math needs immediate perception to verify its principles, but I’m talking about the source of those principles a priori, which is why I started out with primes.

Anyway......I’m ready to let this rest if you are. -

Janus

18kDoesn't the synthetic a priori, according to Kant, require prior actual experience to be able to then realize what is necessarily involved in all possible experience?

Janus

18kDoesn't the synthetic a priori, according to Kant, require prior actual experience to be able to then realize what is necessarily involved in all possible experience?

I imagine that arithmetic started with what are perceptually obvious attributes of groups of different numbers of objects; that is I don't imagine it all started purely abstractly "in the head". Of course I may be wrong, but that seems most plausible to me.

I'm not even sure we're disagreeing, that's how much "in the dark" I am. :halo: -

Janus

18kneither of which are reliant on the least on neuroscience, unless you've got a neurological disorder. — Wayfarer

Janus

18kneither of which are reliant on the least on neuroscience, unless you've got a neurological disorder. — Wayfarer

If we can know ourselves without neuroscience, it may be possible to know ourselves even better with the aid of neuroscience. Don't forget that Varela et al advocated neuroscience as an adjunct to phenomenology: neurophenomenology.

Also, you don't understand disorders without understanding orders. -

Wayfarer

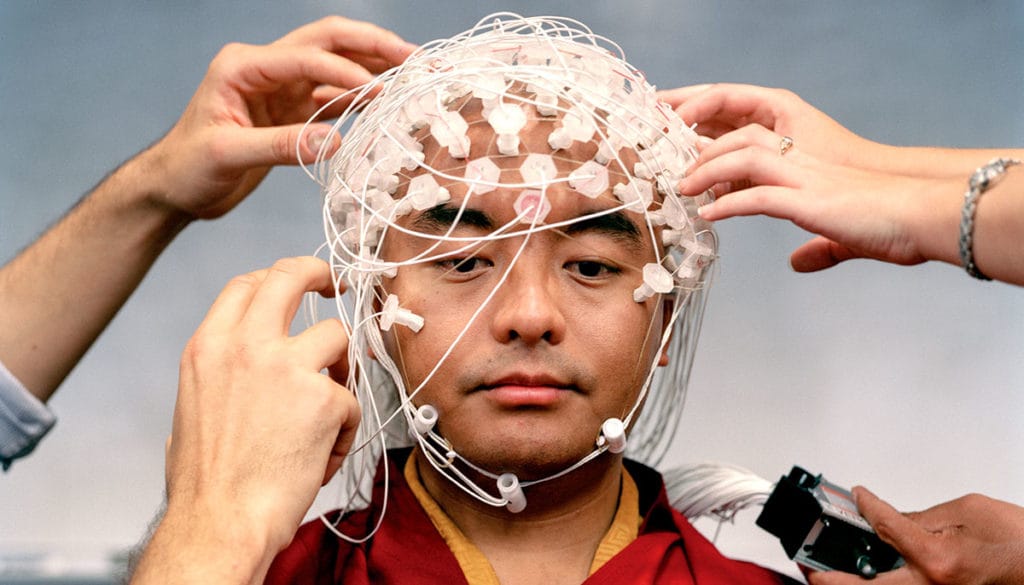

26.1kYes indeed he did. Embodied Mind is still the classic book. Still, I don't know if much of the argument depended on neuroscience, or whether it appealed to neuroscience to make the case more convincing for those inclined to thinking in those terms. I'm always amused by this image:

Wayfarer

26.1kYes indeed he did. Embodied Mind is still the classic book. Still, I don't know if much of the argument depended on neuroscience, or whether it appealed to neuroscience to make the case more convincing for those inclined to thinking in those terms. I'm always amused by this image:

-

Mww

5.4kDoesn't the synthetic a priori, according to Kant, require prior actual experience to be able to then realize what is necessary to all possible experience? — Janus

Mww

5.4kDoesn't the synthetic a priori, according to Kant, require prior actual experience to be able to then realize what is necessary to all possible experience? — Janus

Man, get ready to dodge the tomatoes.....bringing Kant into a discussion analyzing strictly Platonic shadows. Much of Plato is found in Kant, to be sure, but not this.

Yes, we need experience of objects. We need something for synthetic a priori cognitions, principles and such, to have a bearing on, something to which they relate, as a means to understand reality. But the objects.....reality...... don’t give us either those principles or the numbers we use them on.

Iff mathematical principles are created by human reason in response to observations, then the grounds for them must already subsist in reason. Observation isn’t sufficient, in that there is no cognition in perception. Even if mathematical principles are contained in reality, some rational human methodology must still subsist in reason in order to first make sense, then make use, of them. Parsimony suggests they arise in us, not reality, from which the sense of them is given immediately. Which is why I brought up primes. There is no way for us to derive the limitations contained in a number, just from the number itself.

Mathematics is proof of the possibility of synthetic a priori cognitions, but not the only use of them, once their validity is proved. Hume’s mistake. -

Wayfarer

26.1kguess we should simply remove the brain, can't stop now! — Enrique

Wayfarer

26.1kguess we should simply remove the brain, can't stop now! — Enrique

There’s simply no need to reference it. Meaning inheres in the relationship of symbols, not in ‘brain structures’.

What you're not addressing is the 'explanatory gap'. (And beware: not seeing it doesn't amount to refuting it.) -

Janus

18kMan, get ready to dodge the tomatoes.....bringing Kant into a discussion analyzing strictly Platonic shadows. Much of Plato is found in Kant, to be sure, but not this. — Mww

Janus

18kMan, get ready to dodge the tomatoes.....bringing Kant into a discussion analyzing strictly Platonic shadows. Much of Plato is found in Kant, to be sure, but not this. — Mww

I'm not talking about Plato though ( OK, I may have gone off topic, but the topic of this thread is shadowy in any case); I'm talking specifically about how recognition of objects, and of the ways that objects can be arranged, leads to an apprehension of basic arithmetic.

We are not born with the ability to count and calculate, even though we are obviously born with the capacity to develop these abilities in our interaction with the perceived diversifies and similarities of the environments we inhabit.

These abilities, I think it most plausible to believe, are developed in our concrete embodied interactions with the world; they could not be developed in abstraction. Abstractions come afterwards, I am claiming, and only when symbolic language is developed. Recognition, and pattern recognition, come before abstraction and it seems they would be the basis for the development of language. This must be so, since it is obvious that even animals can do it.

When a word for tree was developed and applied to many kinds of trees, the recognition of the patterns of configuration that trees manifest must already have been in place. But no abstract universal or notion of an abstract universal needs to be there for that. That comes later with the elaborate abstract analysis made possible by symbolic language. That's my take on it anyhow. -

Mww

5.4kWhen a word for tree was developed and applied to many kinds of trees, the recognition of the patterns of configuration that trees manifest must already have been in place. — Janus

Mww

5.4kWhen a word for tree was developed and applied to many kinds of trees, the recognition of the patterns of configuration that trees manifest must already have been in place. — Janus

True enough, but what if the care isn’t for words, but the origins of them, be what they may? Even to say words are mere inventions, they are always invented in reference to something. The word tree may very well refer to an object of experience, but what of words that refer to immaterial objects? And furthermore, what of immaterial objects that have words, which cannot be experienced at all, as opposed to immaterial objects that have words and we then physically construct their objects in order to acquire experience of them? In any case, because of the manifest distinctions in the references words represent, there must be something in common to them all, and at the same time, must be sufficient causality for their invention.

it isn’t recognition of patterns we want to know about, it being common across species; it’s word development, which is not common at all.

—————-

We are not born with the ability to count and calculate, even though we are obviously born with the capacity to develop these abilities in our interaction with the perceived diversifies and similarities of the environments we inhabit. — Janus

And we’re back to development, this time, abilities. Sounds like we’re justifying Locke’s notion of human tabula rasa, insofar as we’re all mentally empty when we arrive in the world. Which raises the question....if we’re empty and have to develop everything, how is that possible without the innate means to develop? Because the means for experience is necessary, and given the logical necessity of time, it follows there must be something like a first experience. How is....for convenience...our earliest experience possible in the first place, without that which is already present to make it possible? It is contradictory, or at least abysmally circular, to suppose we develop the means for experience, when it is the means for experience claimed to make them possible.

————

But no abstract universal or notion of an abstract universal needs to be there for that. That comes later with the elaborate abstract analysis made possible by symbolic language. — Janus

If all the above is the case, this part cannot be true. There must be abstract universals, having nothing whatsoever to do with language, in order to make human experience possible, and in order to make it possible for humans to develop language.

Now, back to Plato and by association, Kant, which in both are found the conceptions of universals and forms, albeit of different configurations and locations. Not sure about Plato, but in Kant, universals and forms are found in the human mind, more accurately, in human pure reason a priori, and exactly, forms are found in intuition and universals are found in understanding. Forms relate to what we sense, universals relate to what we think.

————-

Sooooo........

(...are you ready hey are you ready for this

Are you hangin’ on the edge of your seat?...)

These abilities, I think it most plausible to believe, are developed in our concrete embodied interactions with the world; they could not be developed in abstraction. — Janus

How can the contingency of concrete embodied interactions with the world, EVER serve in the development of necessary (analytic, irreducible) truth, which formal logic and mathematics ALWAYS gives? Again....Hume’s mistake. Relying on empirical inference derived from mere habit, to justify that of which the contradiction is impossible.

Nahhhh....the justifications for our developments are found in their conformity to experience, insofar as we can’t buck Mother Nature, but the development themselves must always arise from abstractions antecedent to experience.

A = A no matter what A is.

That this is caused by that says nothing whatsoever about every possible this.

1 + 1 will always equal 2 no matter what 1’s and 2’s look like or stand for.

————-

That's my take on it anyhow. — Janus

Yep, me too. It’s all good. Something to pass the time, waiting or football to come on the talkin’ picture box. -

Enrique

845What you're not addressing is the 'explanatory gap'. — Wayfarer

Enrique

845What you're not addressing is the 'explanatory gap'. — Wayfarer

Resolving the explanatory gap and hard problem is exactly what I'm into. I think it will be addressed by quantum biology eventually, but technicalities - the specific quanta and mechanisms involved - have not yet been unveiled by research, though I've got preliminary ideas. Some of you have probably already read many of my posts about it on this site, but for those who haven't and might be interested, give this thread of mine a look: Uniting CEMI and Coherence Field Theories of Consciousness. Any of my threads on qualia, quantum mechanics, consciousness or perception will give still more of a sense for the reasoning. If you've got insights or questions for me, I'd like to discuss. -

Janus

18kit isn’t recognition of patterns we want to know about, it being common across species; it’s word development, which is not common at all. — Mww

Janus

18kit isn’t recognition of patterns we want to know about, it being common across species; it’s word development, which is not common at all. — Mww

You may find this article interesting: https://www.smithsonianmag.com/science-nature/human-ancestors-may-have-evolved-physical-ability-speak-more-25-million-years-ago-180973759/ -

Wayfarer

26.1kResolving the explanatory gap and hard problem is exactly what I'm into — Enrique

Wayfarer

26.1kResolving the explanatory gap and hard problem is exactly what I'm into — Enrique

As I said in response to one of your OP's, I honestly don't think you're grasping the problem. It's a matter of perspective - the 'hard problem of consciousness' is a different kind of problem to the kinds of issues that science can tackle. Not because it's complex, but because science provides objective analysis of causal relationships. 'Objective' is the key word. The problem that Chalmer's legendary paper brings up is not that it's objectively difficult to understand the nature of conscious experience, but that it's not an objective phenomenon at all. It's not a matter of providing 'a mechanism' - that is still within the domain of third-person cognitive science. It is that first-person consciousness is of a different order - or is ontologically distinct - from the domain of objective phenomena. But I've said that quite a few times, and it doesn't seem to register.

Interesting, but notice the caveats. It is not proposing an explanation of how syntactical speech arose, but how sounds became associated with images, and how different vocalisations might have been formed - which, I take it, is still within the domain of stimulus and response. It's when meaning becomes abstracted that language really took off. See this review of Noam Chomsky and Robert Berwick's book 'Why Only Us?' which ponders the question of how the ability to convey meaningful ideas through speech might have evolved.

My view is that, certainly, h. sapiens evolved, pretty much as discovered (although the details keep shifting) but that once the ability to abstract and reason developed, then humans escape from biological determinism. In other words, we can discover things that are not dictated by evolutionary development as such, we 'transcend the biological'. Tremendously unpopular and politically-incorrect view, of course. -

Janus

18kMy view is that, certainly, h. sapiens evolved, pretty much as discovered (although the details keep shifting) but that once the ability to abstract and reason developed, then humans escape from biological determinism. In other words, we can discover things that are not dictated by evolutionary development as such, we 'transcend the biological'. Tremendously unpopular and politically-incorrect view, of course. — Wayfarer

Janus

18kMy view is that, certainly, h. sapiens evolved, pretty much as discovered (although the details keep shifting) but that once the ability to abstract and reason developed, then humans escape from biological determinism. In other words, we can discover things that are not dictated by evolutionary development as such, we 'transcend the biological'. Tremendously unpopular and politically-incorrect view, of course. — Wayfarer

I agree with this. When the ability to abstract was realized through symbolic language we were no longer constrained to follow the ageless patterns of instinct, and the rest is history. Morphological mutations which enabled us to form diverse vowel sounds and grasp objects (opposable thumb) coupled with the common animal ability to recognize pattern (without which no biologically complex organism would be able to perceived their environments) enabled the genesis of language.

I wouldn't say we can totally "transcend the biological" though; but we can certainly break the chains of genetically enforced patterns of behavior. Culture, more and more elaborated, then allows us to do things simply for their own sake, just for the love of them; so we have the arts, literature, music and religion. I would say science too, as that involves free exercise of the creative imagination as much as the arts, but it also has practical significance, as it enables development of new technologies which (could anyway if they were managed wisely) have survival value. -

Enrique

845The problem that Chalmer's legendary paper brings up is not that it's objectively difficult to understand the nature of conscious experience, but that it's not an objective phenomenon at all. It's not a matter of providing 'a mechanism' - that is still within the domain of third-person cognitive science. It is that first-person consciousness is of a different order - or is ontologically distinct - from the domain of objective phenomena. — Wayfarer

Enrique

845The problem that Chalmer's legendary paper brings up is not that it's objectively difficult to understand the nature of conscious experience, but that it's not an objective phenomenon at all. It's not a matter of providing 'a mechanism' - that is still within the domain of third-person cognitive science. It is that first-person consciousness is of a different order - or is ontologically distinct - from the domain of objective phenomena. — Wayfarer

Sorry for the tangent, but this is interesting. Why is that a problem? What is Chalmers wanting to explain? Does he think it's impossible to overcome certain prejudicial notions that arise from first-person consciousness?

This is drawn from a previous conversation I had with you in a different thread:

The reason I think a quantum theory of consciousness could be a leap beyond current neuroscience in solving the hard problem is because, if we consider visualizing an image in our minds or feeling a sensation, the image or sensation is no longer merely produced by action potentials or neurotransmitters as some mysterious supervenient substance, it is the quantum superposition, precisely. The resonant color of the superposition is the subjective color of the mental image, and the quantum resonance of the sensation is the feeling. We will have identity rather than correlation, no gap between matter and percepts, and the basic mind/body problem is resolved. Of course it will turn out to be more complex than only that, but research in principle might be able to model percepts as if they are objects.

This does not diminish the fact that a subjective aspect of experience exists which in its stark immediacy proves ineffable or personal from a certain perspective, but we would be able to perform feats such as creating elements of humanlike subjectivity in electronic devices or repairing, treating and enhancing the physiology and biochemistry of subjectivity in organisms because this subjectivity will at that point be modeled as a material substance with physical structure.

A partial blending of objectivity with subjective experience will surmount the explanatory gap insofar as it relates to humanity's common fund of theoretical knowledge, continuing the progression that has occurred in psychology and neuroscience already. Whether or not humanity is capable of embracing the explanation on an existential or practical level might be the problem Chalmers sees. -

Wayfarer

26.1kWhat is Chalmers wanting to explain? Does he think it's impossible to overcome certain prejudicial notions about consciousness that arise from subjectivity? — Enrique

Wayfarer

26.1kWhat is Chalmers wanting to explain? Does he think it's impossible to overcome certain prejudicial notions about consciousness that arise from subjectivity? — Enrique

It's not that, and certainly not a matter of prejudice.

The really hard problem of consciousness is the problem of experience. When we think and perceive, there is a whir of information-processing, but there is also a subjective aspect. As Nagel (in 'What is it like to be a Bat') has put it, there is something it is like to be a conscious organism. This subjective aspect is experience. When we see, for example, we experience visual sensations: the felt quality of redness, the experience of dark and light, the quality of depth in a visual field. Other experiences go along with perception in different modalities: the sound of a clarinet, the smell of mothballs. Then there are bodily sensations, from pains to orgasms; mental images that are conjured up internally; the felt quality of emotion, and the experience of a stream of conscious thought. What unites all of these states is that there is something it is like to be in them. All of them are states of experience.

It is undeniable that some organisms are subjects of experience. But the question of how it is that these systems are subjects of experience is perplexing. Why is it that when our cognitive systems engage in visual and auditory information-processing, we have visual or auditory experience: the quality of deep blue, the sensation of middle C? How can we explain why there is something it is like to entertain a mental image, or to experience an emotion? It is widely agreed that experience arises from a physical basis, but we have no good explanation of why and how it so arises. Why should physical processing give rise to a rich inner life at all? It seems objectively unreasonable that it should, and yet it does.

If any problem qualifies as the problem of consciousness, it is this one. In this central sense of "consciousness", an organism is conscious if there is something it is like to be that organism, and a mental state is conscious if there is something it is like to be in that state. — David Chalmers, Facing up to the Hard Problem

As it happens, and even though I agree with the thrust of this, I think it could be explained better. Where Chalmers uses the term 'experience', I think the correct word to use is 'being'. What he's saying is that no purely objective account of the mind is the same as 'the nature of experience'; describing an experience is not the same as having an experience. And the capacity for experience is unique to beings, who are the subjects of experience (even very simple beings, but not inorganic nature - this is not panpsychism).

It's also crucial to note that the word 'phenomena' means 'that which appears'; but the subject of experience is not 'a phenomena', but the interpretive agency to whom phenomena appear. As such, the subject of experience is never within the field of vision in the objective examination of phenomena. That's what makes it a 'hard problem' - not that it's devilishly complicated, or that we have to unravel and trace how billions of neural connections work to 'create consciousness', but because it requires a different stance or perspective to that assumed by the natural sciences. The natural sciences begin with the 'criterion of objectivity' - they start with what is given to the senses (hence, empiricism) and reason mathematically (that is, quantitatively) on that basis to make predictions and test hypotheses. But they can't apply that methodology to 'the nature of being', because 'being', as such, is never an object of experience, but the experiencing subject.

It has been remarked by some philosophers of science that this observation actually originated with the Indian philosophy of the Upaniṣads in the saying that 'the hand cannot grasp itself, the eye cannot see itself'. 1

The 'new mysterians' say that, therefore, the nature of mind is a terribly complicated problem, it's beyond our scientific capacity to solve. But that's also wrong - it's not that it's terribly complicated, it's that they're looking at it the wrong way. It takes a different stance, a different attitude, which is associated with a different worldview or way-of-being.

continuing the progression that has occurred in psychology and neuroscience already. — Enrique

I'm sceptical that psychology has made much 'progress' to speak of. And neuroscience is invaluable for the treatment of conditions and ameliorative technologies, like providing prosthetic enhancements to paralysis victims, but whether or how that represents 'progress' in existential terms is another matter.

we would be able to perform feats such as creating elements of humanlike subjectivity in electronic devices — Enrique

Haven't you seen Blade Runner? -

TheMadFool

13.8ksubject of experience is never within the field of vision in the objective examination of phenomena. That's what makes it a 'hard problem' - not that it's devilishly complicated, or that we have to unravel and trace how billions of neural connections work to 'create consciousness', but because it requires a different stance or perspective to that assumed by the natural sciences. — Wayfarer

It has been remarked by some philosophers of science that this observation actually originated with the Indian philosophy of the Upaniṣads in the saying that 'the hand cannot grasp itself, the eye cannot see itself'. — Wayfarer

What about metacognition or self-reflection? I could train to be a neuroscientist, self-experiment and come to some objective conclusions regarding my consciousness? I'm the subject of my own analysis. -

Wayfarer

26.1kpoint still holds. You can look at a reflection of your eyes but you don't see yourself seeing. You only see.

Wayfarer

26.1kpoint still holds. You can look at a reflection of your eyes but you don't see yourself seeing. You only see.

Welcome to The Philosophy Forum!

Get involved in philosophical discussions about knowledge, truth, language, consciousness, science, politics, religion, logic and mathematics, art, history, and lots more. No ads, no clutter, and very little agreement — just fascinating conversations.

Categories

- Guest category

- Phil. Writing Challenge - June 2025

- The Lounge

- General Philosophy

- Metaphysics & Epistemology

- Philosophy of Mind

- Ethics

- Political Philosophy

- Philosophy of Art

- Logic & Philosophy of Mathematics

- Philosophy of Religion

- Philosophy of Science

- Philosophy of Language

- Interesting Stuff

- Politics and Current Affairs

- Humanities and Social Sciences

- Science and Technology

- Non-English Discussion

- German Discussion

- Spanish Discussion

- Learning Centre

- Resources

- Books and Papers

- Reading groups

- Questions

- Guest Speakers

- David Pearce

- Massimo Pigliucci

- Debates

- Debate Proposals

- Debate Discussion

- Feedback

- Article submissions

- About TPF

- Help

More Discussions

- Other sites we like

- Social media

- Terms of Service

- Sign In

- Created with PlushForums

- © 2026 The Philosophy Forum