-

baker

6k

baker

6k

In Early Buddhism, they speak of the six senses, with the intellect being the sixth. And if you look at the suttas, they talk about taking pleasure in ideas/thoughts as being simply yet another pleasure, like the pleasure of eating or engaging in sex. They do talk about gross and refined pleasures (and gross and subtle forms of suffering); but the point is that these pleasures (or sufferings) are considered as being on a spectrum, not different categories.Eudomonia in Aristotelian philosophy is linked with virtue and with fulfilling your life's purpose (telos). I don't think it's difficult to differentiate those kinds of aims from the hedonistic pursuit of pleasure. Nor do I find it difficult to differentiate the faculty of reason from that of sensation. — Wayfarer

As things stand, I'm finding it difficult to relate to the differentiation you make (and which I am aware is very common in Western culture at large).

(In Dhammic religions in general, philosophical pursuits (seeking and taking pleasure in thoughts, ideas) is considered a hedonistic pursuit, mind you, hence the characteristic anti-intellectualism that can be sometimes found among their practitioners.) -

baker

6k

baker

6k

Humans also have a social dimension; they are epistemically dependent on other humans; they have internalized and have access to knowledge accumulated by other humans, which can help them navigate individual deficiencies.So the premise of hedonism that pleasure and pain determine what is good and bad seems to me inherently flawed. Our senses are simply too easy to fool. — Tzeentch

Social trust and epistemic dependence on other humans can give us reason to doubt our particular experiences: experiences that can be temporarily pleasurable, but harmful in the long run. Beside that doubt, they can also help us navigate them and endure the temporary displeasure that comes from depriving ourselves from things that are temporarily pleasurable but harmful in the long run.

Left to oneself, one single human doesn't seem likely to be able handle the problem.

- - -

How do you think this can be put into practice?To sum it all up, we need to move on/away from what, by my analysis, is a rather superficial understanding, perhaps even a total misunderstanding, of happiness/sorrow which is to think that happiness/sorrow are themselves objectives either to attain/avoid and arrive at the truth that the state of wellbeing is the real goal. With this realization we can perhaps get rid of the go-betweens viz. happiness/sorrow and all the complications/paradoxes/problems/dilemmas that go with them. — TheMadFool -

Tzeentch

4.4kReasoning PLUS experience can, sure, but you were just doubting the reliability of experience, and when pressed for what grounds we have to doubt it, gave just reasoning alone as an answer.

Tzeentch

4.4kReasoning PLUS experience can, sure, but you were just doubting the reliability of experience, and when pressed for what grounds we have to doubt it, gave just reasoning alone as an answer.

My point overall is that while the conclusions reached from some experiences can indeed turn out to be wrong, the way we find that out is via more experiences, so it’s still ultimately experience that we’re relying on. — Pfhorrest

I think we can use reasoning alone to come to conclusions about what is good and bad, without having to experience it first-hand. I think we do this all the time, on this forum for example. Unless you wish to classify reason as an experience in the same way that pain and pleasure are experiences. But I wouldn't agree with such a classification. -

Wayfarer

26.1kIn Early Buddhism, they speak of the six senses, with the intellect being the sixth. And if you look at the suttas, they talk about taking pleasure in ideas/thoughts as being simply yet another pleasure, like the pleasure of eating or engaging in sex. — baker

Wayfarer

26.1kIn Early Buddhism, they speak of the six senses, with the intellect being the sixth. And if you look at the suttas, they talk about taking pleasure in ideas/thoughts as being simply yet another pleasure, like the pleasure of eating or engaging in sex. — baker

There nevertheless must be an element that discerns the meaning of dharma and elects to pursue it. Furthermore it’s a Buddhist dogma that only humans can hear and respond to the dharma - hence the expression ‘this precious human birth’. -

Pfhorrest

4.6kBut your moral objectivism amounts to the same thing. — baker

Pfhorrest

4.6kBut your moral objectivism amounts to the same thing. — baker

It very explicitly does not. That's the point of replicating others' experiences: so we don't have to take their word for it.

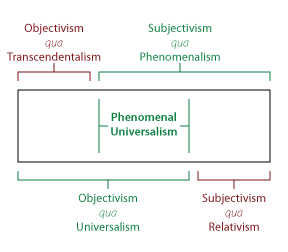

You never explained your bizarre "empathy is incompatible with objectivism" comment, but I'd guess from that that you take "objectivism" to mean what I called "transcendentalism", which would require taking someone's word for it, which is why I'm against that, as I explicitly said. The only sense of "objectivism" I support is "universalism", the view that something being good or bad doesn't depend on what anyone thinks or says... because that would just be taking someone's word for it too.

Just like (according to a scientific worldview) reality doesn't depend on what anyone thinks about it, but there's still nothing about reality that's beyond observation: it's not relative, it's universal, but it's also not transcendent, it's entirely phenomenal.

we can use reasoning alone to come to conclusions about what is good and bad — Tzeentch

Only when we already have some known-true propositions about what's good or bad to reason from. But when we're starting from scratch, or are lost in radical doubt, where do we get any such moral propositions to start that reasoning process from? I can think of nothing other than experience, or else just taking someone's word for it. -

Tzeentch

4.4kOnly when we already have some known-true propositions about what's good or bad to reason from. But when we're starting from scratch, or are lost in radical doubt, where do we get any such moral propositions to start that reasoning process from? I can think of nothing other than experience, or else just taking someone's word for it. — Pfhorrest

Tzeentch

4.4kOnly when we already have some known-true propositions about what's good or bad to reason from. But when we're starting from scratch, or are lost in radical doubt, where do we get any such moral propositions to start that reasoning process from? I can think of nothing other than experience, or else just taking someone's word for it. — Pfhorrest

Ok, but how does this make a case for hedonism? -

Pfhorrest

4.6kOk, but how does this make a case for hedonism? — Tzeentch

Pfhorrest

4.6kOk, but how does this make a case for hedonism? — Tzeentch

Hedonism (specifically ethical hedonism, the topic of the thread) is about appealing to experiences (of things feeling good or bad) as grounds to call something good or bad.

Hopefully I don't need to make the obvious case against just taking someone's word for it. -

baker

6k

baker

6k

Which is not incompatible with considering the intellect to be a sense.There nevertheless must be an element that discerns the meaning of dharma and elects to pursue it. — Wayfarer

Why should there be a problem with considering the intellect to be a sense?

(Note a parallel in Western antiquity, what "common sense" originally meant.) -

Becky

45I can’t quote philosophers. I have read a few. But may I weigh in?

Becky

45I can’t quote philosophers. I have read a few. But may I weigh in?

I am in hedonist. I’m also an atheist. People that are religious when they find out I’m atheist say “but you’re so nice”. I have a tendency to give a lot of things away.

Religion tries to explain what we can’t understand. As we will never know what happens after we die there is religion. Religion helps control the population.

Humans are the only species that can alter their environment. However, altering environment is like shitting in your nest. If you don’t understand everything is in connected you understand nothing. A true Zen saying “Nothing is what I want”. Even Buddhist don’t allow women to be in the upper echelon. Humans think that we are morally superior to other species. And we used to think that the universe revolved around us. We are nothing. Everything in this universe is from the big bang. Now it is just devolving into chaos. I believe in math and chemistry. I don’t take a vantage of other people. I dislike seeing people control others. I ask questions. Personally, I can’t wait to die. -

Wayfarer

26.1kWhy should there be a problem with considering the intellect to be a sense? — baker

Wayfarer

26.1kWhy should there be a problem with considering the intellect to be a sense? — baker

What does the Euclidean theorem look like? The ability to grasp a rational idea of that kind is different to a sensory impression, surely.

Also the Buddhist ‘manas’ is something like ‘organ of perception of ideas’. There are other terms for intellect in the Buddhist lexicon, notably, Buddhi, and also Citta, but considering all of those details are out of scope for this thread. The key word in western philosophy was ‘nous’ which has sadly fallen out of use. -

Becky

45But what is intellect? We used to think that animals weren’t self-aware or couldn’t make tools. That’s been proven wrong. Being a white suburban female if I was dropped into Chicago ghetto would I have the intellect to survive?

Becky

45But what is intellect? We used to think that animals weren’t self-aware or couldn’t make tools. That’s been proven wrong. Being a white suburban female if I was dropped into Chicago ghetto would I have the intellect to survive?

True,The transfer of knowledge is no longer genetic (cannibalism, Inbreeding). That’s why the printing press and the Internet are so important. Basic Greek mathematics and principles came from Egypt. But Egypt Restricted that knowledge within their priesthood. Greek philosophers dispersed that knowledge. Knowledge is power. How do we know that other species don’t have ideas? Simply because we don’t see it does not mean it’s not there. -

baker

6k

baker

6k

What started off this tangent was this:What does the Euclidean theorem look like? The ability to grasp a rational idea of that kind is different to a sensory impression, surely.

/.../

Also the Buddhist ‘manas’ is something like ‘organ of perception of ideas’. There are other terms for intellect in the Buddhist lexicon, notably, Buddhi, and also Citta, but considering all of those details are out of scope for this thread. The key word in western philosophy was ‘nous’ which has sadly fallen out of use. — Wayfarer

And we're back to the problem of who gets to be the arbiter of what is virtue and what isn't.Seems to me that hedonism always wants to avoid this conclusion - to say there’s no real difference between pleasant sensations and eudomonaic happiness (which is the happiness that comes from the pursuit of virtue.) One can, for example, attain happiness in the contemplation of verities, which surely can’t be reduced to sensation alone, and which only a rational mind can entertain. — Wayfarer

I think that depends on the measure of epistemic autonomy that an individual person is assumed to have.What does the Euclidean theorem look like? The ability to grasp a rational idea of that kind is different to a sensory impression, surely. — Wayfarer

The more epistemic autonomy a person is assumed to have (ie. the more the individual person is identified with their mind), the starker the difference between the first five senses and the intellect. And vice versa.

But how does a particular person know what their life's purpose is?Eudomonia in Aristotelian philosophy is linked with virtue and with fulfilling your life's purpose (telos). — Wayfarer

Surely the ancient Greeks weren't individualists who believed that every man and woman (!) is able and should define their own life purpose for themselves, quite divorced from the social roles and expectations placed upon them by other people.

I think it depends on the particular life purpose for the particular person.I don't think it's difficult to differentiate those kinds of aims from the hedonistic pursuit of pleasure.

Take, for example, a professional culinary connoisseur. A person like that eats, tastes food for a living, it's their telos. Eating, tasting food is also a hedonistic pursuit of pleasure. So where's the difference between such a person's telos and hedonistic pursuit of pleasure? Can this be answered without demoting the profession of culinary connoisseurship to something unvirtuous? -

baker

6k

baker

6k

But one cannot replicate others' experiences.It very explicitly does not. That's the point of replicating others' experiences: so we don't have to take their word for it. — Pfhorrest

For example, I don't drink coffee, because it makes me sleepy. Many people drink coffee in the morning specifically for the purpose that it "wakes them up". So which is it? Who is right, who is wrong? Who has the right experience of drinking coffee in the morning? I or they? Is there an objectively right way to experience drinking coffee in the morning?

Objectivisms are authoritarian and assume to be impersonal/suprapersonal. Yet, contrary to that, it is always a particular person, a Tom or a Dick who makes the claim that X is really such and such, and that Harry is in the wrong if he doesn't see it that way.You never explained your bizarre "empathy is incompatible with objectivism" comment, but I'd guess from that that you take "objectivism" to mean what I called "transcendentalism", which would require taking someone's word for it, which is why I'm against that, as I explicitly said. The only sense of "objectivism" I support is "universalism", the view that something being good or bad doesn't depend on what anyone thinks or says... because that would just be taking someone's word for it too.

There is no room for empathy in objectivism, because the objectivist already assumes to know better.

But it still comes down to whose observation matters.Just like (according to a scientific worldview) reality doesn't depend on what anyone thinks about it, but there's still nothing about reality that's beyond observation: it's not relative, it's universal, but it's also not transcendent, it's entirely phenomenal.

The problem you're actually indirectly talking about is the problem of epistemic dependence. -

Becky

45But who defines virtue? Lots of religionists people think they are virtuous by restricting and controlling others to what their “god(s)” tell them is right.

Becky

45But who defines virtue? Lots of religionists people think they are virtuous by restricting and controlling others to what their “god(s)” tell them is right.

Your comment “ Surely the ancient Greeks weren't individualists who believed that every man and woman (!) is able and should define their own life purpose for themselves, quite divorced from the social roles and expectations placed upon them by other people.”

Isn’t that why Socrates died? He was condemned to death for his Socratic method of questioning. -

Pfhorrest

4.6kAnd we've talked about how these experiences alone are too easy to fool to serve as a guide. — Tzeentch

Pfhorrest

4.6kAnd we've talked about how these experiences alone are too easy to fool to serve as a guide. — Tzeentch

But we're asking how we know that they are so unreliable. Your answer was "reason". I responded that reason alone can't get you much of anywhere, you need something to reason from to begin with, and I asked "where do you get that, besides experience (or else taking someone's word for it)?". Assuming we agree that taking someone's word for it is no good, that leaves us appealing to experience to tell us that experience is unreliable.

Which works if what we mean is that further experiences can tell us that some limited earlier experiences were not the full picture; I agree with that completely. But in that case you're still relying on experience generally. And if you can't rely on experience generally because experience tells you so... that's circular there.

But one cannot replicate others' experiences.

For example, I don't drink coffee, because it makes me sleepy. Many people drink coffee in the morning specifically for the purpose that it "wakes them up". So which is it? Who is right, who is wrong? Who has the right experience of drinking coffee in the morning? I or they? Is there an objectively right way to experience drinking coffee in the morning? — baker

Observations always only tell you a relationship between observers and the world; the predictions based on those observations are that certain types of observers will or won’t observe certain things. It is those relationships that can be objective (as in universal), not just the object-end of them.

E.g. even how things look or sound etc are not the same between every observer. There are different kinds of colorblindness, actual blindness in different degrees, tetrachromaticity, different degrees of hearing sensitivity or deafness to different pitches of sound, people who can or can’t smell or taste various things or to whom they smell or taste different, etc.

An ethical science would likewise have features of subjects of experience baked into both its input and its output.

Objectivisms are authoritarian — baker

Transcendentalisms are, yes, because they demand that you take someone's word for it, because nobody can check the results for themselves. But universalism is not necessarily transcendentalism, just as phenomenalism (non-transcendentalism) is not necessarily relativism (non-universalism).

But it still comes down to whose observation matters. — baker

On a universalist account, everyone's observation matters; that's what makes it universalist.

Physical science is universalist about reality in that if someone doesn't experience the same phenomena that everyone else does, even after completely controlling for the objects of said experience (the environment / experiment / etc), we go figure out what's different about the subject (the person) such that they experience the same object differently, and adjust our theories to correctly predict what that kind of subject will experience as well. An ethical science would have to do likewise. -

Wayfarer

26.1kBut how does a particular person know what their life's purpose is? — baker

Wayfarer

26.1kBut how does a particular person know what their life's purpose is? — baker

In pre-modern cultures, individuals were not expected to 'forge their own destiny', it was handed to them as a result of their caste, social status, and so on. Part of the advent of modern liberalism is just that requirement - to 'find your destiny' as the saying has it. And that can be challenging and daunting but I would like to think it's at least possible. (This essay on Max Weber has some interesting things to say about that.)

In any case, Aristotelian ethics, or virtue ethics, aren't predicated on the idea that we have a pre-made destiny that we ought to fulfill. In that understanding, 'virtue is its own reward', because it instills habits, which become character, which become destiny. (This is the subject of a major book on ethical theory, After Virtue by Alisdair McIntyre.)

There nevertheless must be an element that discerns the meaning of dharma and elects to pursue it.

— Wayfarer

It's not clear how this is the case. — baker

If it were not the case, Buddhism would never have come into existence. Recall the story of the ascetic that walked past the Buddha after the enlightenment and more or less shrugged it off, saying 'it could be' that he had realised the goal. Then at the Deer Park sermon in Benares, five other ascetics took the Buddha at his word and so the Sangha was formed.

That capacity to discern the truth ('viveka' in Sanskrit) is different to sensation.

I think we are indoctrinated by empiricism, that only knowledge based on sensation is for real. That is why it seems so awfully difficult to differentiate rational knowledge and sensation when really the difference ought to be obvious.

An ethical science would have to do likewise. — Pfhorrest

In the physical sciences, part of the method is to agree on the nature of the object of analysis, and what should be considered in that analysis. Anything which is not germane to that analysis is then rejected or bracketed out. But that approach s not possible when considering ethical and normative judgement in respect of the living of life, as in that case, we're not outside of or apart from the object of enquiry, 'we are what we seek to know.'

Transcendentalisms...demand that you take someone's word for it, because nobody can check the results for themselves. — Pfhorrest

In Buddhist ethical theory, the aspirant is presumed to be able to validate the teachings by first-hand insight, through their attaining of that insight in the living of the principles. The key term is 'ehi-passiko', 'seeing for oneself'. In practice there are obstacles to that, first and foremost the difficulties of realising such goals, but you can't say that in principle nobody it able to do so. (See this verse for discussion of the difference between 'taking on conviction' and 'direct discernment'.)

And there are, or there have been in the past, similar kinds of insights in Western philosophy.

According to Pierre Hadot, twentieth- and twenty-first-century academic philosophy has largely lost sight of its ancient origin in a set of spiritual practices that range from forms of dialogue, via species of meditative reflection, to theoretical contemplation. These philosophical practices, as well as the philosophical discourses the different ancient schools developed in conjunction with them, aimed primarily to form, rather than only to inform, the philosophical student. The goal of the ancient philosophies, Hadot argued, was to cultivate a specific, constant attitude toward existence, by way of the rational comprehension of the nature of humanity and its place in the cosmos. This cultivation required, specifically, that students learn to combat their passions and the illusory evaluative beliefs instilled by their passions, habits, and upbringing. 1

So the results 'can be checked for yourself' although if such possibilities are rejected out of hand, then it remains a practical impossibility. In other words, it requires a certain kind of openness to those modes of discourse. (Maybe it's the case that we've been inoculated against any idea of 'higher truth' by dogmatic religion, specifically Protestantism.) -

Wayfarer

26.1kIsn’t that why Socrates died? He was condemned to death for his Socratic method of questioning. — Becky

Wayfarer

26.1kIsn’t that why Socrates died? He was condemned to death for his Socratic method of questioning. — Becky

Indeed! But the principles that Socrates articulated in the Apology were then to become central to the works of Plato, thence Aristotle, and ultimately the whole of Western culture. Of course it's true that over the course of history, the Church then assimilated that classical wisdom and declared themselves the arbiters of virtue. But you can reject the Church without rejecting the Socratic idea of virtue. -

Pfhorrest

4.6kwe're not outside of or apart from the object of enquiry, 'we are what we seek to know.' — Wayfarer

Pfhorrest

4.6kwe're not outside of or apart from the object of enquiry, 'we are what we seek to know.' — Wayfarer

I’d say that is as true of reality as it is of morality, precisely because of phenomenalism about reality, empirical realism, like Kant’s. All we can know about is how things appear to us, so we are a part of the object of enquiry there too. Likewise, all we can know about morality is what does or doesn’t feel good to us — all of us, not just one of us, just like in empirical investigations of reality.

In Buddhist ethical theory, the aspirant is presumed to be able to validate the teachings by first-hand insight, through their attaining of that insight in the living of the principles. The key term is 'ehi-passiko', 'seeing for oneself'. In practice there are obstacles to that, first and foremost the difficulties of realising such goals, but you can't say that in principle nobody it able to do so. — Wayfarer

That would not be transcendentalism in the sense I mean then, since if you can experience it for yourself it is definitionally phenomenal. -

Wayfarer

26.1kThat would not be transcendentalism in the sense I mean then, since if you can experience it for yourself it is definitionally phenomenal. — Pfhorrest

Wayfarer

26.1kThat would not be transcendentalism in the sense I mean then, since if you can experience it for yourself it is definitionally phenomenal. — Pfhorrest

Phenomena are ‘what appears’. I think what is supposed to become clear through Buddhism is not necessarily the subject of experience per se, but an understanding about, or insight into, the nature of experience, generally. That is articulated (although rarely so) as the distinction between experience and realisation.

In Buddhism, we distinguish between spiritual experiences and spiritual realizations. Spiritual experiences are usually more vivid and intense than realizations because they are generally accompanied by physiological and psychological changes. Realizations, on the other hand, may be felt, but the experience is less pronounced. Realization is about acquiring insight. Therefore, while realizations arise out of our spiritual experiences, they are not identical to them. Spiritual realizations are considered vastly more important because they cannot fluctuate. 1 -

Tzeentch

4.4kWhich works if what we mean is that further experiences can tell us that some limited earlier experiences were not the full picture; I agree with that completely. But in that case you're still relying on experience generally. — Pfhorrest

Tzeentch

4.4kWhich works if what we mean is that further experiences can tell us that some limited earlier experiences were not the full picture; I agree with that completely. But in that case you're still relying on experience generally. — Pfhorrest

To connect two experiences together and figure out what they mean, one has to rely on reason to tell the relation between the two.

Eating sugar brings pleasure. That is an experience.

Developing diabetes brings pain. That is also an experience.

These two experiences seperately do not tell us anything. We need another element, which I argue is reason, to connect the dots. -

Pfhorrest

4.6kI think what is supposed to become clear through Buddhism is not necessarily the subject of experience per se, but an understanding about, or insight into, the nature of experience, generally. — Wayfarer

Pfhorrest

4.6kI think what is supposed to become clear through Buddhism is not necessarily the subject of experience per se, but an understanding about, or insight into, the nature of experience, generally. — Wayfarer

That would still not be transcendental in the sense I mean then, because it's not an a posteriori claim about actual particulars of either reality or morality ("this kind of thing exists", "this kind of thing is good", etc) at all, but an a priori claim about the philosophical matters of how to even answer questions about those things (the nature of experience being one factor of that topic).

These two experiences seperately do not tell us anything. We need another element, which I argue is reason, to connect the dots. — Tzeentch

Sure, but I'm not arguing that we don't need to rely on reason, only that we do need to rely on experience. Reason alone gets us nowhere, it just stops us from heading down dead ends. To make actual progress in figuring out any of the particulars, we have to rely on experience as well. -

baker

6k

baker

6k

And in the process of doing so, the person gets designated as "abnormal". "Wrong". "Defective". "Inferior".Physical science is universalist about reality in that if someone doesn't experience the same phenomena that everyone else does, even after completely controlling for the objects of said experience (the environment / experiment / etc), we go figure out what's different about the subject (the person) such that they experience the same object differently, and adjust our theories to correctly predict what that kind of subject will experience as well. An ethical science would have to do likewise. — Pfhorrest

Once such qualifiers are introduced, we're back to might makes right. -

baker

6k

baker

6k

Do you think that the Nazis didn't feel good about themselves and their ideas of what counts as virtue? That they didn't feel rewarded by what they considered virtuous behavior?In any case, Aristotelian ethics, or virtue ethics, aren't predicated on the idea that we have a pre-made destiny that we ought to fulfill. In that understanding, 'virtue is its own reward', because it instills habits, which become character, which become destiny. — Wayfarer

If virtue would somehow be something that is baked into the fabric of the universe, so that it would operate by laws similar to those in physics, then there'd be no problem. So, for example, if you did X, you'd feel good, and if you did Y, you'd feel crappy. But it doesn't work that way.

People can kill, rape, and pillage, and feel good about it. Or they can kill, rape, and pillage, and not feel good about it.

It's one's kamma that makes one attracted to the Buddha's teachings. -- So goes the Buddhist reasoning for conversion.There nevertheless must be an element that discerns the meaning of dharma and elects to pursue it.

— Wayfarer

It's not clear how this is the case.

— baker

If it were not the case, Buddhism would never have come into existence. Recall the story of the ascetic that walked past the Buddha after the enlightenment and more or less shrugged it off, saying 'it could be' that he had realised the goal. Then at the Deer Park sermon in Benares, five other ascetics took the Buddha at his word and so the Sangha was formed.

There are extra-Buddhist/non-Buddhist conceptualizations for religious conversion to Buddhism (usually inspired by Western secular anthropology and religiology, or inspired by Christianity somehow). And then there are Buddhism-internal explanations for why a person takes to the Buddha's teachings.

The notion that a person "discerns the meaning of dharma and elects to pursue it" is incompatible with Buddhist doctrine, at least as far as persons with less than stream entry are concerned.

I don't understand what you mean here.I think we are indoctrinated by empiricism, that only knowledge based on sensation is for real. That is why it seems so awfully difficult to differentiate rational knowledge and sensation when really the difference ought to be obvious.

This is a westernized verificationist approach. A cradle Buddhist would never set out to "validate the teachings" or to "verify" them.In Buddhist ethical theory, the aspirant is presumed to be able to validate the teachings by first-hand insight, through their attaining of that insight in the living of the principles. The key term is 'ehi-passiko', 'seeing for oneself'. In practice there are obstacles to that, first and foremost the difficulties of realising such goals, but you can't say that in principle nobody it able to do so.

It doesn't make your point. Look what Sariputta says:(See this verse for discussion of the difference between 'taking on conviction' and 'direct discernment'.)

And as for me, I have known, seen, penetrated, realized, & attained it by means of discernment. I have no doubt or uncertainty that the faculty of conviction... persistence... mindfulness... concentration... discernment, when developed & pursued, gains a footing in the Deathless, has the Deathless as its goal & consummation."

He started off with conviction (!!), and then he did this and that, and then he came to certainty. It's a circular, self-referential, self-fulfilling, self-proving activity. No wonder "it works".

The holy grail -- epistemic autonomy.And there are, or there have been in the past, similar kinds of insights in Western philosophy.

IOW, it's about training oneself, developing oneself, cultivating oneself into becoming a particular type of person. This is how one "sees for oneself". It's not about verifying whether some claims are true or not. It's about making oneself be such that one comes to see those claims as true, as good.According to Pierre Hadot, twentieth- and twenty-first-century academic philosophy has largely lost sight of its ancient origin in a set of spiritual practices that range from forms of dialogue, via species of meditative reflection, to theoretical contemplation. These philosophical practices, as well as the philosophical discourses the different ancient schools developed in conjunction with them, aimed primarily to form, rather than only to inform, the philosophical student. The goal of the ancient philosophies, Hadot argued, wasto cultivate a specific, constant attitude toward existence, by way of the rational comprehension of the nature of humanity and its place in the cosmos. This cultivation required, specifically, that students learn to combat their passions and the illusory evaluative beliefs instilled by their passions, habits, and upbringing. 1

It's similar to vocational training. One doesn't engage in vocational training in order to test the claims made by the specific field of expertise. One does it to learn, to earn expertise, a vocation.

You don't test if baking "works". You do it to become a baker.

I think the problem is, rather, that the matter is approached in a pseudoscientific manner of "experimenting, testing, and verifying claims for yourself". Such experimenting etc. is impossible, at least as long as one doesn't have epistemic autonomy. And if one had it, one wouldn't need to test etc. anything anyway.So the results 'can be checked for yourself' although if such possibilities are rejected out of hand, then it remains a practical impossibility. In other words, it requires a certain kind of openness to those modes of discourse. (Maybe it's the case that we've been inoculated against any idea of 'higher truth' by dogmatic religion, specifically Protestantism.) -

Pfhorrest

4.6kAnd in the process of doing so, the person gets designated as "abnormal". "Wrong". "Defective". "Inferior". — baker

Pfhorrest

4.6kAnd in the process of doing so, the person gets designated as "abnormal". "Wrong". "Defective". "Inferior". — baker

No, that's quite the opposite. Consider for example recognizing neurodiversity, as in, the non-defectiveness of autistic (etc) experience patterns. Things that please and calm many neurotypical people can be very distressing and displeasing to neurodivergent people. The position you assumed I was arguing would be to call whatever pleases "normal" (neurotypical) people good, and neurodivergent people defective for not finding that good. But what I'm actually advocating is that we say it's good to act one way toward a neurotypical person (the way that they find pleasant and calming), but bad to act that same way toward a neurodivergent person (because they'll find it distressing and displeasing).

Just like a theory of color that makes predictions hinging on "normal" three-color vision needs to make that dependency explicit or else it will end up making false predictions from the perspective of colorblind people. A truly universal theory of color vision will have to make predictions that "normal" people will see one type of thing and colorblind people will see a different type of thing. -

Wayfarer

26.1kIf virtue would somehow be something that is baked into the fabric of the universe, so that it would operate by laws similar to those in physics, then there'd be no problem. So, for example, if you did X, you'd feel good, and if you did Y, you'd feel crappy. But it doesn't work that way. — baker

Wayfarer

26.1kIf virtue would somehow be something that is baked into the fabric of the universe, so that it would operate by laws similar to those in physics, then there'd be no problem. So, for example, if you did X, you'd feel good, and if you did Y, you'd feel crappy. But it doesn't work that way. — baker

It's because we can choose. Not only can choose, but have to choose.

Regarding wether there is a faculty of discrimination, as distinct from mind/manas, I posed this question on Stack Exchange, and was told there is a term Paṭisambhidā: formed from paṭi- + saṃ- + bhid, where paṭi + saṃ should probably be understood as 'back together', and the verbal root bhid means 'to break, split, sever'. Rhys Davids and Stede propose that a literal rendering would be "resolving continuous breaking up", and gloss this as 'analysis, analytic insight, discriminating knowledge'; moreover, they associate it with the idea of 'logical analysis' (Pali-English Dictionary, p. 400.2). Bhikkhu Nyanatiloka similarly renders the term as 'analytical knowledge', but also as 'discrimination' (Buddhist Dictionary, p. 137). Bhikkhu Ñāṇamoli voices a divergent view in a note to his translation of in Buddhaghosa's Visuddhimagga, XIV.8, where he renders paṭisambhidā as 'discrimination': -

baker

6k

baker

6k

Cultivation in accordance with the Buddha's teachings leads to a particular and irreversible ability to discern Dhamma. Without this cultivation, a person cannot rightfully be said to be able to choose between Dhamma and adhamma (because they can't tell the difference).Regarding wether there is a faculty of discrimination, as distinct from mind/manas, I posed this question on Stack Exchange, and was told there is a term Paṭisambhidā: formed from paṭi- + saṃ- + bhid, where paṭi + saṃ should probably be understood as 'back together', and the verbal root bhid means 'to break, split, sever'. Rhys Davids and Stede propose that a literal rendering would be "resolving continuous breaking up", and gloss this as 'analysis, analytic insight, discriminating knowledge'; moreover, they associate it with the idea of 'logical analysis' (Pali-English Dictionary, p. 400.2). Bhikkhu Nyanatiloka similarly renders the term as 'analytical knowledge', but also as 'discrimination' (Buddhist Dictionary, p. 137). Bhikkhu Ñāṇamoli voices a divergent view in a note to his translation of in Buddhaghosa's Visuddhimagga, XIV.8, where he renders paṭisambhidā as 'discrimination': — Wayfarer

It's similar to the difference between an ordinary person and a trained gymnast: both have a body, both can do some physical exercises, yet the gymnast can do exercises that the ordinary person can't (and can't even conceive how to do them). It's not the case that one would have a body and the other wouldn't; nor that one would have physical prowess and the other one wouldn't.

It seems that for the psychologically normal person, morality is never a matter of choice -- such a person "just knows what the right thing to do" is (for such a person, the issue is only whether they are able to do it).If virtue would somehow be something that is baked into the fabric of the universe, so that it would operate by laws similar to those in physics, then there'd be no problem. So, for example, if you did X, you'd feel good, and if you did Y, you'd feel crappy. But it doesn't work that way.

— baker

It's because we can choose. Not only can choose, but have to choose. — Wayfarer

But beyond that, I don't understand where you're going with the way you replied.

Welcome to The Philosophy Forum!

Get involved in philosophical discussions about knowledge, truth, language, consciousness, science, politics, religion, logic and mathematics, art, history, and lots more. No ads, no clutter, and very little agreement — just fascinating conversations.

Categories

- Guest category

- Phil. Writing Challenge - June 2025

- The Lounge

- General Philosophy

- Metaphysics & Epistemology

- Philosophy of Mind

- Ethics

- Political Philosophy

- Philosophy of Art

- Logic & Philosophy of Mathematics

- Philosophy of Religion

- Philosophy of Science

- Philosophy of Language

- Interesting Stuff

- Politics and Current Affairs

- Humanities and Social Sciences

- Science and Technology

- Non-English Discussion

- German Discussion

- Spanish Discussion

- Learning Centre

- Resources

- Books and Papers

- Reading groups

- Questions

- Guest Speakers

- David Pearce

- Massimo Pigliucci

- Debates

- Debate Proposals

- Debate Discussion

- Feedback

- Article submissions

- About TPF

- Help

More Discussions

- Other sites we like

- Social media

- Terms of Service

- Sign In

- Created with PlushForums

- © 2026 The Philosophy Forum