-

miosim

21The origin of concept that the “whole is greater than the sum of its parts” is attributed to Aristotle (Metaphysics , Book 8), however the closest I found there is "...the whole is not, as it were, a mere heap, but the totality is something besides the parts, there is a cause of unity ..."

miosim

21The origin of concept that the “whole is greater than the sum of its parts” is attributed to Aristotle (Metaphysics , Book 8), however the closest I found there is "...the whole is not, as it were, a mere heap, but the totality is something besides the parts, there is a cause of unity ..."

Did I miss something?

Thank you -

miosim

21I need to clarify my question. I am curious if Aristotle really said that “whole is greater than the sum of its parts”. If he didn't, who first said this? Does any body know any reputable philosopher who defends this claim?

miosim

21I need to clarify my question. I am curious if Aristotle really said that “whole is greater than the sum of its parts”. If he didn't, who first said this? Does any body know any reputable philosopher who defends this claim?

Personally I believed that it is OK to use "the whole ... its parts" as a figurative speech, but philosophically and especially scientifically it is FUNDOMENTELY wrong. -

BC

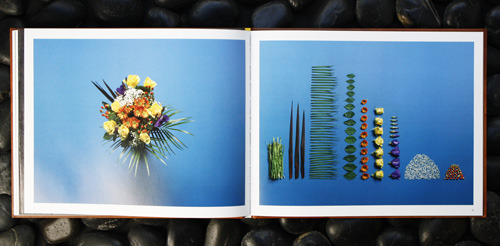

14.3kThere is a book, The Art of Clean Up, which organizes whole objects into their parts, like this bouquet of flowers:

BC

14.3kThere is a book, The Art of Clean Up, which organizes whole objects into their parts, like this bouquet of flowers:

Which is greater: the live plant parts forming a whole bouquet, or the disassembled bouquet laid out in rows as parts? The parts are the same, the mass is the same, but one is a bouquet, the other one isn't.

Theoretically, we could take your brain apart and lay out the neurons, vessels, white matter, etc. side by side on a very large table. Which would be greater? Your disassembled brain (parts) or your whole brain?

Clearly, the whole is greater than the sum of its parts, because as part of the whole, nerve cells, flower petals, and so on can do things that they can't do alone. Actually, as parts, nerve cells can't do much of anything. -

Michael

16.9kAccording to this, it's from Metaphysics, with the translation being "the totality is not, as it were, a mere heap, but the whole is something besides the parts", so you're right. This is similar to Kurt Koffka's (correctly translated) phrase "the whole is other than the sum of the parts" which itself is sometimes mistranslated as "the whole is greater than the sum of its parts", a translation that Koffka disagrees with.

Michael

16.9kAccording to this, it's from Metaphysics, with the translation being "the totality is not, as it were, a mere heap, but the whole is something besides the parts", so you're right. This is similar to Kurt Koffka's (correctly translated) phrase "the whole is other than the sum of the parts" which itself is sometimes mistranslated as "the whole is greater than the sum of its parts", a translation that Koffka disagrees with.

So it seems the particular term "greater" is a misquote. -

Terrapin Station

13.8kThe Art of Clean Up, which organizes whole objects into their parts, like this bouquet of flowers: — Bitter Crank

Terrapin Station

13.8kThe Art of Clean Up, which organizes whole objects into their parts, like this bouquet of flowers: — Bitter Crank

The problem with that is that I disagree that relations and processes aren't parts. Also, no one saying that a whole is the sum of its parts is saying that relations and processes are not included.

At any rate, @ , I would say that that Aristotle quote is effectively saying "the whole is other than the sum of its parts." -

miosim

21

miosim

21

Bitter Crank

The "sum" is mathematical notation, sort of tool, that could be useful or deceptive, depending how we use it. For example what is the "sum" of one "dog" and one "steak"? If you could ask this question Aristotle, he may respond with long incomprehensive metaphysical talk, say ... if dog will eat the steak the result is "1", otherwise it is "2" etc. However If you ask this question a middle school child he/she may respond that the question is mathematically wrong.

Regarding example of bouquet and its part, the notion of "sum" or "greater" are mathematically or logically inappropriate.

In the example with bouquet the SOMEONE assembles the individual pieces into bouquet. So if you still want to use the mathematical notation as a figurative speech, you should ask the following question:

Is "various parts of bucket" + "someone who put them together" = "bouquet" ?

What is your answear to this question? -

miosim

21

miosim

21

I know that Koffka did not like the translation and firmly corrected students who replaced "other" with "greater". Does it mean that the wisdom of "Whole is greater than the sum of its parts" is (at least partially) originated of incorrect translation? -

miosim

21"Theoretically, we could take your brain apart and lay out the neurons, vessels, white matter, etc. side by side on a very large table. Which would be greater? Your disassembled brain (parts) or your whole brain?

miosim

21"Theoretically, we could take your brain apart and lay out the neurons, vessels, white matter, etc. side by side on a very large table. Which would be greater? Your disassembled brain (parts) or your whole brain?

Clearly, the whole is greater than the sum of its parts, because as part of the whole, nerve cells, flower petals, and so on can do things that they can't do alone. Actually, as parts, nerve cells can't do much of anything"

I own you the response for these examples as well.

Regarding the brain and its neurons and other components conceder the following analogy:

Lets have a manufacture and take apart all its building and equipment. Then let force all its employers to lay down on the ground face down.

We understand that under these condition employer cannot do much. Do we need to ask why? Do we need to ask what is "more" or "less", the striving manufacture or its ruins and horrified employers.

The "whole is more than sum of its part" means nothing. It is a just a bumper sticker, a symbol of our ignorance to understand complex phenomena like brain. -

_db

3.6kClearly, the whole is greater than the sum of its parts, because as part of the whole, nerve cells, flower petals, and so on can do things that they can't do alone. Actually, as parts, nerve cells can't do much of anything. — Bitter Crank

_db

3.6kClearly, the whole is greater than the sum of its parts, because as part of the whole, nerve cells, flower petals, and so on can do things that they can't do alone. Actually, as parts, nerve cells can't do much of anything. — Bitter Crank

This, I would say, is contentious. We could be mereological nihilists and think that the parts of the flower are arranged "flower-wise", but not believe that there is such a thing as a "flower".

So are the arrangements of parts themselves something? Is an arrangement a thing? I would argue that perhaps we ought to see arrangements, or structures, as something parts do. Thus complex static objects don't exist, but what we commonly see as complex static objects are really processes of parts all working together. The act of working together is "something".

As such, there are no strict boundaries between systems. The world is messy. -

BC

14.3kThe "whole is more than sum of its part" means nothing. It is a just a bumper sticker, a symbol of our ignorance to understand complex phenomena like brain. — miosim

BC

14.3kThe "whole is more than sum of its part" means nothing. It is a just a bumper sticker, a symbol of our ignorance to understand complex phenomena like brain. — miosim

No, no, no. The phrase "the whole is more than the sum of its parts" is not a bumpersticker slogan. Its an accurate assessment of a world in which many phenomena (including us) are emergent, always exceeding the sum of our parts.

Another example. A rich delicious soup has a fixed list of ingredients. Eat the raw ingredients ground up together and it won't taste very good. Simmered in a pot for several hours, and it's heavenly. Flavors emerge in the soup that weren't there in the "un-stewed" parts.

I don't know... If you don't get it, you don't get it. No soup for you. -

BC

14.3kcontentious. We could be mereological nihilists and think that the parts of the flower are arranged "flower-wise", but not believe that there is such a thing as a "flower". — darthbarracuda

BC

14.3kcontentious. We could be mereological nihilists and think that the parts of the flower are arranged "flower-wise", but not believe that there is such a thing as a "flower". — darthbarracuda

Maybe we could be mereological nihilists, but we are not -- I'm not anyway. Speak for yourself.

As such, the world is messy. — darthbarracuda

Right, because the soup of many parts boiled over, covering everything up with hot, emergent, whole, complexity. -

Terrapin Station

13.8k

Terrapin Station

13.8k

Way to ignore that relations and processes are parts and that no one saying "the whole is the sum of its parts" is saying that relations and processes aren't included. -

Metaphysician Undercover

14.9kThe real issue here comes about when you consider the logical relationship between "whole" and "part". The part is necessarily a part of a whole. If it is not a part of something, it is no longer a part, it must be a whole. A whole can exist without parts.

Metaphysician Undercover

14.9kThe real issue here comes about when you consider the logical relationship between "whole" and "part". The part is necessarily a part of a whole. If it is not a part of something, it is no longer a part, it must be a whole. A whole can exist without parts.

So when we consider the existence of an object, and specifically the coming into being of the object, it is necessary to conclude that the whole is prior in time to the parts. When the parts come into existence, they are necessarily parts of a whole, so the whole is necessarily prior in time to the parts. This is why the whole is something other than (greater than) the sum of the parts, because the whole may exist even without any parts. -

Metaphysician Undercover

14.9kWhat is an example of an existing object without parts? — jkop

Metaphysician Undercover

14.9kWhat is an example of an existing object without parts? — jkop

Anything which is simple, not compound. -

jkop

1k

jkop

1k

What is an example of an existing object which is anything and simple, not compound?Anything which is simple, not compound. — Metaphysician Undercover -

Wayfarer

26.2kThe nucleus of an atom is comprised of protons and neutrons. This basic model of the atom was developed in the early-twentieth century when protons and neutrons were said to be 'basic building blocks' of matter (although, of course, later it was found that they too consist of smaller particles, namely quarks.)

Wayfarer

26.2kThe nucleus of an atom is comprised of protons and neutrons. This basic model of the atom was developed in the early-twentieth century when protons and neutrons were said to be 'basic building blocks' of matter (although, of course, later it was found that they too consist of smaller particles, namely quarks.)

But there is something wrong even with this account. A bare neutron has a half-life of about eleven and a half minutes; it decays into a proton, an electron and a neutrino. However, once inside the nucleus of an atom, its integration into the higher order intelligibility of the atomic nucleus changes its properties and it remains stable for billions of years. The higher order reality has modified the lower order constituent. Indeed if this did not happen there would be no stable atomic nuclei and no stable chemical substances.

It's an interesting illustration of 'top-down causation'. -

mcdoodle

1.1kWhat is an example of an existing object which is anything and simple, not compound? — jkop

mcdoodle

1.1kWhat is an example of an existing object which is anything and simple, not compound? — jkop

Actually in that section of the Metaphysics Aristotle argues that the abstract has an essential unity: 'all things which have no matter are without qualification essentially unities.' Things with matter are however inescapably matter/form. -

mcdoodle

1.1kExperientially it feels right to me that the whole is at least other than the sum of the parts. If you ever make music you will recognise this. I sing in a choir and the collective feeling when things go right is of a different order from when one is singing individually, or from the notion of a bunch of individuals who happen to be singing with each other. People who play instruments tell me the same.

mcdoodle

1.1kExperientially it feels right to me that the whole is at least other than the sum of the parts. If you ever make music you will recognise this. I sing in a choir and the collective feeling when things go right is of a different order from when one is singing individually, or from the notion of a bunch of individuals who happen to be singing with each other. People who play instruments tell me the same.

The other ontological issue can come up even in 'realism'. (To generalise a point Wayfarer is making) Are for instance abstractions in biology 'reducible' to chemistry or physics? Is 'the economy' reducible to some set of naturalistic terms? Or are there - as I would see it - different levels of abstraction appropriate to different forms of analysis, without the supposed component parts being in some way 'superior' or 'more fundamental'? -

jkop

1k

jkop

1k

It seems to me that an elementary particle is also a compound of the particle plus some property that it has. Or is that just a property of language imposed on the thing described?

Are there unities without parts?'all things which have no matter are without qualification essentially unities.' Things with matter are however inescapably matter/form. — mcdoodle

Interesting. So, could an elementary particle exist without having any real properties by itself but getting properties from other things?The higher order reality has modified the lower order constituent. — Wayfarer -

Wayfarer

26.2kIt seems to me that the concept of 'elementary particle' can't really be sustained any more. The original idea of the atom was literally an 'indivisible particle', but I think it's really been rendered untenable by physics itself; fields are now said to be fundamental, and they're obviously a completely different kind of concept altogether. In any case, many of the particles being chased in the LHC only exist as part of some kind of ensemble, the whole aim of the machine is to break up that ensemble so as to glimpse the elusive 'particles' before they decay. An atom certainly isn't what it used to be.

Wayfarer

26.2kIt seems to me that the concept of 'elementary particle' can't really be sustained any more. The original idea of the atom was literally an 'indivisible particle', but I think it's really been rendered untenable by physics itself; fields are now said to be fundamental, and they're obviously a completely different kind of concept altogether. In any case, many of the particles being chased in the LHC only exist as part of some kind of ensemble, the whole aim of the machine is to break up that ensemble so as to glimpse the elusive 'particles' before they decay. An atom certainly isn't what it used to be.

Actually, this OP has been very useful, because the meaning of the phrase 'the totality is something besides the parts, there is a cause of unity' seems to me a better way of putting it than the usual translation.

In Mongrel's thread on Leibniz I put the analogy of the 'holographic image'. There is a property of holograms, which is that if hologram is broken up, each of the fragments contains the whole image, albeit at a lower resolution than the original. This is one of the paradigmatic examples of the principle of holism. It seems basic in biology also - stem cells, for example, can take on the form of any of the specialised cells in the various organs, depending on the context in which they're put. 'Gene expression' is also regulated by the environment, which is arguably another form of 'top-down' causality. Again, individual cells seem to function according to their context; that seems near to the meaning of Aristotle's phrase also. -

miosim

21The problem with that is that I disagree that relations and processes aren't parts. — Terrapin Station

miosim

21The problem with that is that I disagree that relations and processes aren't parts. — Terrapin Station

Agree -

Metaphysician Undercover

14.9kIt seems to me that an elementary particle is also a compound of the particle plus some property that it has. Or is that just a property of language imposed on the thing described? — jkop

Metaphysician Undercover

14.9kIt seems to me that an elementary particle is also a compound of the particle plus some property that it has. Or is that just a property of language imposed on the thing described? — jkop

I think that to understand the elementary particle we have to relate it to the field. But now the particle appears to be a property of the field. So it may not be truly elementary, as it is the property of something else. But fields are completely conceptual, and no one knows what "field" refers to in reality, it just mathematics which describes the conditions under which elementary particles appear. The elementary particle now appears to be just a part of a larger whole. I think this is what Wayfarer is referring to. But this raises the possibility that "whole" could be something completely different from what we think. -

apokrisis

7.8kOr are there - as I would see it - different levels of abstraction appropriate to different forms of analysis, without the supposed component parts being in some way 'superior' or 'more fundamental'? — mcdoodle

apokrisis

7.8kOr are there - as I would see it - different levels of abstraction appropriate to different forms of analysis, without the supposed component parts being in some way 'superior' or 'more fundamental'? — mcdoodle

Yep. And a telltale fact from hierarchy theory is how wholes act to simplify their parts. Wholes refine their components so as to make themselves ... even more easy to construct.

Take a human level example of an army. For an army to make itself constructible, it must take large numbers of young men and simplify their natures accordingly. It must turn people with many degrees of freedom (any variety of personal social histories) into simpler and more uniform components.

So wholes are more than just the sum of their parts ... in that wholes shape those parts to serve their higher order purposes. Wholes aren't accidental in nature. They produce their own raw materials by simplifying the messy world to a collection of parts with no choice but to construct the whole in question.

It seems to me that the concept of 'elementary particle' can't really be sustained any more. The original idea of the atom was literally an 'indivisible particle', but I think it's really been rendered untenable by physics itself; fields are now said to be fundamental — Wayfarer

Even the Cosmos had to impose simplification on its parts so as to exist. To expand and cool, it needed particles to radiate and absorb. It need a pattern of events that would let a thermal unwinding happen.

That is why you get order out of chaos. Reality needs to form dissipative structure that has the organisation to turn a sloppy directionless mess into an efficient entropic gradient.

Turn a full soda bottle of water upside down and it glugs inefficiently until a vortex forms and the bottle can suddenly drain fast and efficient.

Wholes make their parts by reducing degrees of freedom and creating components with little choice but to eternally re-construct that which is their causal master. -

Wayfarer

26.2kI think I understand that account, but it's still too mechanist for my liking. I will just have to keep meditating on the 'fundamental principle' until it becomes more evident but I am of the view that whatever it is, intelligence or sentience is intrinsic to it.

Wayfarer

26.2kI think I understand that account, but it's still too mechanist for my liking. I will just have to keep meditating on the 'fundamental principle' until it becomes more evident but I am of the view that whatever it is, intelligence or sentience is intrinsic to it. -

miosim

21The phrase "the whole is more than the sum of its parts" is not a bumpersticker slogan. Its an accurate assessment of a world in which many phenomena (including us) are emergent, always exceeding the sum of our parts. — Bitter Crank

miosim

21The phrase "the whole is more than the sum of its parts" is not a bumpersticker slogan. Its an accurate assessment of a world in which many phenomena (including us) are emergent, always exceeding the sum of our parts. — Bitter Crank

The claim for ontological emergence is my prime target. As you pointed correctly the phrase "the whole is more than the sum of its parts" is an essence and roots of the theory of emergence. It is why to defeat this theory I need to start with its roots.

Another example. A rich delicious soup has a fixed list of ingredients. Eat the raw ingredients ground up together and it won't taste very good. Simmered in a pot for several hours, and it's heavenly. Flavors emerge in the soup that weren't there in the "un-stewed" parts. — Bitter Crank

You are right that taste of delicious soup is better (more) than taste of its ingredients. However you are right for the wrong reason, because you just forgot to include in your "equation" SOMEONE who tastes the soup. By adding this SOMEONE to your "equation" you may find the whole is now could be "more", "equal", or "less" that the "sum" of its parts, depending on the subjective taste of this SOMEONE. For example, I personally don't like Cesar salad (whole), but prefer its components (fresh vegetable) instead.

Your example with taste is a typical rhetorical example of emergence and is usually goes like that:

"Taste of sugar, a system phenomenon, could not be found in the carbon, hydrogen, and oxygen atoms that constitute components of sugar molecules". This example, limits the whole to sugar only while the another crucial element of the system is missing; SOMEONE who tastes the sugar and declares its taste vs. the taste of its component. Indeed for this SOMEONE taste of sugar and its purified components causes a very different taste (sensation perceived in the mouth and throat on contact with a substance). However to answer why it is different we don't need to invoke emergence; biochemistry and biology should be enough.

In the majority of examples, upon which the system approach is based, there is an exclusion of the invisible SOMEONE who designs, put together, tastes, or observes. Without this SOMEONE, the system property, like the taste, would not exist at all.

Omitting the creator or user of the system is the far most common mistake in emergentism. For example, a complex computer is built from the simple semiconductor components and it seems that the ‘computational intelligence’ of the computer is a new emerging phenomenon, because it cannot be found in its parts. However, the complexity of the computer is also due to the property (complexity) of human intelligence, which is not seen while we are observing the computer. Therefore, human intelligence is also one of the system’s causal powers and his or her properties determine the complexity of the semiconductor components, the complex wiring of the logic diagram, and sophisticated algorithms. In other words, there are no emerging properties in this example and

the properties of a computer could be reduced to the properties of its elements, including the creators of this computer.

Welcome to The Philosophy Forum!

Get involved in philosophical discussions about knowledge, truth, language, consciousness, science, politics, religion, logic and mathematics, art, history, and lots more. No ads, no clutter, and very little agreement — just fascinating conversations.

Categories

- Guest category

- Phil. Writing Challenge - June 2025

- The Lounge

- General Philosophy

- Metaphysics & Epistemology

- Philosophy of Mind

- Ethics

- Political Philosophy

- Philosophy of Art

- Logic & Philosophy of Mathematics

- Philosophy of Religion

- Philosophy of Science

- Philosophy of Language

- Interesting Stuff

- Politics and Current Affairs

- Humanities and Social Sciences

- Science and Technology

- Non-English Discussion

- German Discussion

- Spanish Discussion

- Learning Centre

- Resources

- Books and Papers

- Reading groups

- Questions

- Guest Speakers

- David Pearce

- Massimo Pigliucci

- Debates

- Debate Proposals

- Debate Discussion

- Feedback

- Article submissions

- About TPF

- Help

More Discussions

- All this talk about Cogito Ergo Sum... what if Decartes and you guys are playing tricks on me?

- Did Descartes prove existence through cogito ergo sum?

- Cogito ergo sum? Is there an absolute level of existence?

- Cogito ergo sum. The greatest of all Philosophical blunders!

- Does The Hard Problem defeat Cogito Ergo Sum?

- Other sites we like

- Social media

- Terms of Service

- Sign In

- Created with PlushForums

- © 2026 The Philosophy Forum