-

Monist

41If you were to start from scratch to study the fields of philosophy like epistemology, logic, metaphysics, ethics, philosophy of religion/science/mind etc., not to just know them, but being able to establish knowledge on any ground, to establish a ground you can build your beliefs on, how would your ultimate planning look like?

Monist

41If you were to start from scratch to study the fields of philosophy like epistemology, logic, metaphysics, ethics, philosophy of religion/science/mind etc., not to just know them, but being able to establish knowledge on any ground, to establish a ground you can build your beliefs on, how would your ultimate planning look like?

(If you could include details like, what subject you would start with and/or what materials and platforms you would make use of, I would appreciate that)

I welcome well-thought and, strategically smart answers. -

I like sushi

5.3kI would, and do, simply write down what interests me and try and answer questions that interest me. Then look into how others have approached those questions.

I like sushi

5.3kI would, and do, simply write down what interests me and try and answer questions that interest me. Then look into how others have approached those questions.

Basically, follow your interests and the horizon will broaden.

If you’re talking about more ‘academic scholarship’ then there are several ways to approach this to have a broad understanding of philosophical development. Russell’s The History of Western Philosophy is a pretty good place to start, and it can lead you into other more refined studies.

I think it is pretty foolish in the current age to lack a decent understanding of science. Perhaps looking into ideas about economic, political and educational development over human history would be a fruitful approach too.

Like I’ve said many times before a must read for anyone interested in philosophical discourse and writing should certainly read Kant’s Critique of Pure Reason, but I wouldn’t recommend beginning with that text as it would likely put people off the entire field of interest in the first few pages.

Note: Logic is certainly the bedrock of philosophical pursuits so a thorough study of that is sure to set the person up with something more tangible. -

TheHedoMinimalist

460My answer to this question is certainly biased towards my own philosophical interests but I would start by trying to find answers to the questions in life that everyone needs to address. I think those important questions include the following:

TheHedoMinimalist

460My answer to this question is certainly biased towards my own philosophical interests but I would start by trying to find answers to the questions in life that everyone needs to address. I think those important questions include the following:

1. Should I have children?

2. Should I get married?

3. What kind of career should I pursue?

4. What does it mean to say that one’s quality of life is good?

5. Do I have any duties towards anyone and what are those duties?

6. Is being alive a good thing overall for you?

7. If not, could you do something to make it a good thing?

8. If not, is it worth trying to commit suicide?

9. If being alive is a good thing overall right now for you, could it ever become a bad thing overall?

10. If so, how?

11. Is there an independent badness to death that is unrelated to the badness of the process of dying or the badness of losing out on more of the good things in life?

12. What kind of house should you buy?

13. Is it preferable to try to work harder or is it better to focus more on trying to save more money?

14. What kind of romantic relationship, if any, should one pursue?

15. When is it acceptable to take on financial debt?

16. What kind of friendships should you try to develop?

17. Do you have any bad habits that you should eliminate?

It’s kinda difficult to try to find philosophical content that deal with those questions. Because of this, I started a YouTube channel a while back that focuses on these types of questions. I would also strongly recommend Shelly Kegan’s lecture series on the subject of Death on YouTube. This lecture series has been most influential to me since it introduced me to Axiology. Here’s some other good lecture series that I recommend:

1. Robert Sapolsky’s Human Behavioral Biology series

2. Robert Shiller’s Financial Markets series -

I like sushi

5.3kTo add ... avoid reading guides like the plague and DO NOT read introductions by translators other than to note issues with particular words.

I like sushi

5.3kTo add ... avoid reading guides like the plague and DO NOT read introductions by translators other than to note issues with particular words.

By this I mean that you should avoid this the first time around and come to your own conclusions about the text written by the philosopher before being spoon fed someone else’s interpretation. All philosophers are basically working from others anyway so why bother to distance yourself fro the text by seeing it through the lens of another? I understand that this is generally necessary for university students as they simply don’t have time to read through anything themselves.

Note: I do use reading guides, and read introductions, after I have made up my own mind about a text. It’s not the quickest method but I believe it’s the most honest approach if you keep in mind your understanding in and of itself is limited (that changes once your horizons open up a little more and come to understand the landscape a little better). -

Wayfarer

26.1kIf you want to study the subject, which is not necessarily the same as developing a personal philosophy, I strongly recommend studying it historically. Start with the pre-Socratics, then read forward - widely, synoptically and historically. Try and get a feel for the questions that were being grappled with and the historical circumstances in which they arose. Get a feeling for dialectic - that is one of the most elusive aspects of philosophy. Don’t neglect Plato. Find some question that nags at you, then try and find sources that seem to be dealing with the same questions. Learn to feel the questions, not simply verbalise them.

Wayfarer

26.1kIf you want to study the subject, which is not necessarily the same as developing a personal philosophy, I strongly recommend studying it historically. Start with the pre-Socratics, then read forward - widely, synoptically and historically. Try and get a feel for the questions that were being grappled with and the historical circumstances in which they arose. Get a feeling for dialectic - that is one of the most elusive aspects of philosophy. Don’t neglect Plato. Find some question that nags at you, then try and find sources that seem to be dealing with the same questions. Learn to feel the questions, not simply verbalise them.

An anecdote - I was browsing one of the better bookshops in my city some time back, and I happened to overhear a conversation between a gentleman who was apparently a pretty bigshot metaphysics lecturer and someone who was considering graduate studies. Fascinating and wide-ranging conversation, whoever this guy was - wish I’d found out! Anyway, one remark he made, kind of tongue-in-cheek, stuck with me. ‘The Greeks, the Medievals, and the Germans - that’s all you need to know. The rest is rubbish!’ As I say, not meant entirely seriously, kind of a rhetorical device, but made an interesting point.

The other crucial meta-question that I think is necessary to grapple with is the meaning of modernity. When I studied philosophy formally - two undergraduate years - Descartes was introduced as ‘the first modern philosopher’. Crucial to know why that is, and to read Descartes, then Hume, Berkeley, Locke, and - absolutely central - Kant’s Critique of Pure Reason (see this OP.)

It’s a vast territory but well worth exploring. In my opinion philosophy is one of the great treasures of Western culture. -

Mww

5.4kFrom the time you hit the elementary school sandbox......

Mww

5.4kFrom the time you hit the elementary school sandbox......

......has already been established.a ground you can build your beliefs on — Monist

The vast majority of humanity made it through life without ever cracking a book on philosophy, and without giving the discipline of philosophy a conscious thought. Which raises the question, given the lack of necessity or even the obvious usefulness, what does the study of philosophy actually do for those indulging in it? Seems like it would be nothing but a source of somewhat more than trivial information, with respect to how those writing the books, think. In short, merely a matter of relative interest.

Experience will always be the prime determinant for philosophical understanding, but understanding itself, as a purely cognitive faculty, is always theoretical. Every human has experiences, which makes explicit every human already has a philosophical understanding, however unknown its constructions may be to him. It follows that the study of theoretical philosophy with respect to pure thought, as the foundation of how the ground for the building of beliefs became established in the first place, is all one really needs.

And, as everybody knows, there is only one such speculative philosopher worth mentioning, that being the Privatdozent in mathematics and physics, and The Esteemed Professor of Logic and Metaphysics at Königsberg. One may read whoever he wants for background, but he should get seriously involved with Kant, to obtain the standard on which all subsequent cognitive philosophy, whether affirmation or negation, is obliged to follow.

My opinion only, of course. -

Pfhorrest

4.6kTo get a broad acquaintance with the history of the field and its range of thoughts, I think these are probably the most important authors to read:

Pfhorrest

4.6kTo get a broad acquaintance with the history of the field and its range of thoughts, I think these are probably the most important authors to read:

Socrates (via Plato)

Plato

Aristotle

Aquinas

Descartes

Locke

Kant

And then you should acquaint yourself with the foremost thinkers in the fields of:

Philosophy of Language

Philosophy of Art

Philosophy of Mathematics

Ontology / Metaphysics

Philosophy of Mind

Epistemology

Philosophy of Education

Philosophy of Religion

Metaethics

Philosophy of will

Ethics (especially utilitarians and deontologists)

Political philosophy

Existentialism / “philosophy of life”

In my formal education I overlooked the middle of that historical list (Aquinas and the Scholastic generally) and the beginning and end of that topic list (the first three and the last one), and only later realized their place in the big picture and wished I could go back and give myself this general study structure to work from. -

jgill

4kBy this I mean that you should avoid this the first time around and come to your own conclusions about the text written by the philosopher before being spoon fed someone else’s interpretation. All philosophers are basically working from others anyway so why bother to distance yourself fro the text by seeing it through the lens of another? I understand that this is generally necessary for university student — I like sushi

jgill

4kBy this I mean that you should avoid this the first time around and come to your own conclusions about the text written by the philosopher before being spoon fed someone else’s interpretation. All philosophers are basically working from others anyway so why bother to distance yourself fro the text by seeing it through the lens of another? I understand that this is generally necessary for university student — I like sushi

My knowledge of philosophy is limited, but I recall my prof giving the opposite advice after I tried reading several of the well-known philosophers like Kant in their own words. Some of those icons wrote poorly. -

alcontali

1.3kIf you were to start from scratch to study the fields of philosophy like epistemology, logic, metaphysics, ethics, philosophy of religion/science/mind etc., not to just know them, but being able to establish knowledge on any ground, to establish a ground you can build your beliefs on, how would your ultimate planning look like? — Monist

alcontali

1.3kIf you were to start from scratch to study the fields of philosophy like epistemology, logic, metaphysics, ethics, philosophy of religion/science/mind etc., not to just know them, but being able to establish knowledge on any ground, to establish a ground you can build your beliefs on, how would your ultimate planning look like? — Monist

The "philosophy of X" is much easier to grasp than "general philosophy", especially if you already have a reasonable understanding of X itself.

In that sense, philosophy can be seen as a set of one-argument functions, with X being the argument:

ontologyOf(X) and epistemologyOf(X)

You can pick any X, really.

Say that you want to explore the philosophy of tennis (X=tennis). It would undoubtedly work, but you will need a good understanding of tennis.

Ontology (What is it?) and epistemology (How do we justify knowledge?) are in my impression the only sub-disciplines that make sense.

There are serious issues with the other sub-disciplines.

Logic is a part of mathematics. It is not philosophy. It has been successfully axiomatized now. Ethics competes and then spectacularly loses from morality, which is grounded in religious law. Metaphysics amounts to an utmost dumb exercise in infinite regress, which has has never produced anything of value or anything worth knowing.

Non-mathematical logic and non-religious ethics are childish, inept, and incompetent, while metaphysics is clueless.

Only ontology and epistemology make sense. -

I like sushi

5.3kOf course. In university you don’t have the time so you have to rely on second-hand sources - I said that in my post.

I like sushi

5.3kOf course. In university you don’t have the time so you have to rely on second-hand sources - I said that in my post.

I understand that this is generally necessary for university students as they simply don’t have time to read through anything themselves. — I like sushi -

unenlightened

10kThe academy exists because learning is social.

unenlightened

10kThe academy exists because learning is social.

One stands on the shoulders of the ancients. -

180 Proof

16.4kIf you were to start from scratch to study ... philosophy ... ? — Monist

180 Proof

16.4kIf you were to start from scratch to study ... philosophy ... ? — Monist

I'd start with a comprehensive history of philosophy in order to acquaint myself with the most general questions & intractable conceptual problems major philosophers (in the West) have preoccupied themselves with for the last two and a half (plus) millennia. To that end I'd recommend Peter Adamson's podcast & book series A history of philosophy without any gaps:

• Classical Philosophy, vol. 1 (2014)

• Philosophy in the Hellenistic and Roman Worlds,

vol. 2 (2015)

• Philosophy in the Islamic World, vol. 3 (2018)

• Medieval Philosophy, vol. 4 (2019)

(Subsequent volumes to follow ...)

... to establish knowledge on any ground,

Generally, philosophy consists in understanding (i.e. reflective criteria for discriminating knowledge claims from non-knowledge claims) and does not "establish knowledge" (e.g. explanatory theories re: sciences, arts, histories, politics, etc) itself.

... to establish a ground you can build your beliefs on,

Preparatory (A-B-C) studies, which IMO are indispensable, for studying & using philosophy: (A) elementary logic, (B) elementary set theory & (C) cognitive psychology. -

god must be atheist

5.1kSelf-Studying Philosophy

I somehow can't believe philosophy can study its own self. I am very much on the opinion that a human must get involved there somewhere, somehow, in the process. -

Artemis

1.9k

Artemis

1.9k

I think Kenneth Burke's Unending Conversation metaphor pretty much captures what any approach comes down to in the end:

"Imagine that you enter a parlor. You come late. When you arrive, others have long preceded you, and they are engaged in a heated discussion, a discussion too heated for them to pause and tell you exactly what it is about. In fact, the discussion had already begun long before any of them got there, so that no one present is qualified to retrace for you all the steps that had gone before. You listen for a while, until you decide that you have caught the tenor of the argument; then you put in your oar. Someone answers; you answer him; another comes to your defense; another aligns himself against you, to either the embarrassment or gratification of your opponent, depending upon the quality of your ally's assistance. However, the discussion is interminable. The hour grows late, you must depart. And you do depart, with the discussion still vigorously in progress."

That may not seem satisfactory for anyone seeking a structured approach... but I'm afraid he captures the impossibility thereof. The Conversation has been going on too long with too many voices addressing aspects of too many things in too many ways for there to be anything but a "dive in and see where the current takes you" approach, even with the best laid plans.

As others have mentioned, establish what interests you (which conversations would you care to join?) and then seek out the biggest ideas and and thinkers in those areas, read them, and keep reading from there. Oh, and Cambridge, Norton, and others write pretty good introductory-summary texts of most fields that keep up to date with the most important developments. -

jgill

4kI understand that this is generally necessary for university students as they simply don’t have time to read through anything themselves. — I like sushi

jgill

4kI understand that this is generally necessary for university students as they simply don’t have time to read through anything themselves. — I like sushi

Yes. However, he implied that anyone beginning a study of a particular philosopher should read not only those works, but other's critiques as well. -

alcontali

1.3kYes. However, he implied that anyone beginning a study of a particular philosopher should read not only those works, but other's critiques as well. — jgill

alcontali

1.3kYes. However, he implied that anyone beginning a study of a particular philosopher should read not only those works, but other's critiques as well. — jgill

Applied philosophy is much more accessible than general philosophy.

The philosophyOf(X) is straightforward if you have a reasonable understanding of X, while X could be anything, really.

So, learn something else first, i.e. some kind of applied knowledge (X). Next, figure out the philosophyOf(X). If you grok that properly, only then try to figure out general philosophy, i.e. philosophyOf(X=philosophy), i.e. self-philosophy.

The other way around does not work.

That is why most philosophy majors understand almost nothing about philosophy.

Theory emerges from practice. It never works the other way around. That is why majors in almost any subject will graduate with close to zero understanding of that subject. The only ones who understand the subject are people who have been confronted with solving practical problems in that subject. Everybody else invariably sounds like an idiot. -

jgill

4kThat is why majors in almost any subject will graduate with close to zero understanding of that subject. The only ones who understand the subject are people who have been confronted with solving practical problems in that subject. Everybody else invariably sounds like an idiot. — alcontali

jgill

4kThat is why majors in almost any subject will graduate with close to zero understanding of that subject. The only ones who understand the subject are people who have been confronted with solving practical problems in that subject. Everybody else invariably sounds like an idiot. — alcontali

This seems a bit harsh and I do not agree. However, I will admit that working in an area may clarify and solidify the knowledge gained as an undergraduate. In the academic world the problems don't necessarily have to be practical to have this effect. -

alcontali

1.3kThis seems a bit harsh and I do not agree. However, I will admit that working in an area may clarify and solidify the knowledge gained as an undergraduate. In the academic world the problems don't necessarily have to be practical to have this effect. — jgill

alcontali

1.3kThis seems a bit harsh and I do not agree. However, I will admit that working in an area may clarify and solidify the knowledge gained as an undergraduate. In the academic world the problems don't necessarily have to be practical to have this effect. — jgill

Well, I got recently confronted with how clueless education can be. It defies imagination.

I sent my brother-in-law to a supposedly practical training centre where he was supposed to do a 6-month training in mobile android (phone) development, because that should allow him to get an internship at a software company, with a view on doing a real-world, hands-on project.

For mere paperwork reasons, he will also start later this year a four-year bachelor course in computer science taught during the evenings. That curriculum is supposedly more theoretical, but it actually isn't. It is just more useless.

So, at the software training centre, they insist that he must first do a class in C/C++ because hey, "C/C++ is the core language in computing". So, yes, the operating system's kernel and a small core of libraries in any system may be written in C, but there is no way that any software company will ask a recent training graduate to write any C/C++ code for them. It is just too tricky and too bug-prone.

So, he does not need this skill for his internship in mobile development. Furthermore, very, very few libraries for Android phones are ever written in C/C++. As a developer, you will only see the Java interfaces anyway. So, it is not needed, and they are simply wasting 8 weeks of my brother-in-law's time (which is way too short to learn it properly anyway).

Next, I looked at the source code he was trying to run, and it contained the mention:

#include <windows.h>

What!?

That program is supposed to compile against the Microsoft Windows environment of libraries, which are not present on an Android phone. So, I asked my brother-in-law if he intends to deploy that joke to his phone? No. He doesn't. They just run it on their Windows desktop. It is obvious why. That thing cannot possibly run on an Android phone.

So, what does that course have to do with Android mobile software engineering?

The teacher obviously does not know how to write C/C++ libraries for Android because in that case he would use the proper compiler for that work, which is the gcc crosscompiler, and not Microsoft Visual Studio. So, I assume that he is not even capable of compiling one functioning line of code for Android. He clearly cannot do it.

Still, he insists that what he teaches is "foundational" for mobile development. He is just an arrogant retard who is unaware of his own ineptitude and incompetence.

Most teachers in the academia are like that.

They cannot solve the simplest practical problem in their field, not even to save themselves from drowning, but at the same time, they insist that the bullshit they talk, would be of any interest to their students. It isn't. -

I like sushi

5.3kI don’t disagree. I said that it is a mistake to follow guides with your first reading, but that in university time often doesn’t allow for this.

I like sushi

5.3kI don’t disagree. I said that it is a mistake to follow guides with your first reading, but that in university time often doesn’t allow for this.

I’m assuming the OP is asking in general not looking for advice about how to get a degree in philosophy. There is a big difference. -

Pfhorrest

4.6kI feel like I should give reasons for my earlier recommendations, because looking back on my earlier post I realize it just sounds like a list of authors and fields I like, but it's not just that.

Pfhorrest

4.6kI feel like I should give reasons for my earlier recommendations, because looking back on my earlier post I realize it just sounds like a list of authors and fields I like, but it's not just that.

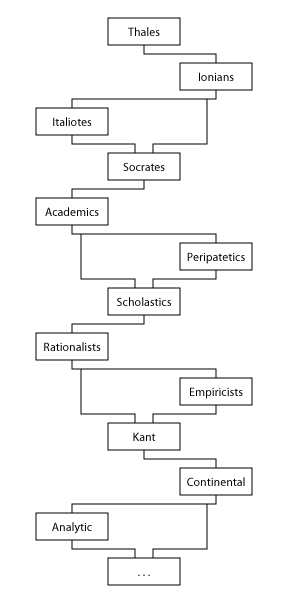

The authors I recommended are because in the history of philosophy, there is a tendency for there to be periods of two opposing camps or trends or schools, and then one philosopher or school of philosophy to unite them, and then two new opposing schools to branch off from that again, back and forth like that. The authors I selected were to give an overview of those opposing schools, and the figures who united them and from whom new ones were formed, as illustrated here:

We don't have a lot of material from Thales, the other Ionians, or the Italiotes (collectively the Presocratics), and their work was really primitive and not super relevant today, so I skipped them entirely. Socrates is really where philosophy as we think of it begins, and his student Plato and Plato's student Aristotle were the founders of the two main opposing schools during the Classical period of philosophy. In the Medieval period things were largely reunited into one school, the Scholastics, of whom Thomas Aquinas is the preeminent figure. The Modern period began with Rene Descartes, the first of what would come to be called Rationalists, and their opposing school, the Empiricists, got their beginning with John Locke. Then Immanuel Kant once again reunited philosophy, until it split again into this Contemporary period's still-unreconciled divide between Analytic and Continental schools, who are too numerous and recent and ongoing to pick preeminent figures for. So that's why I recommend those authors for a historical overview.

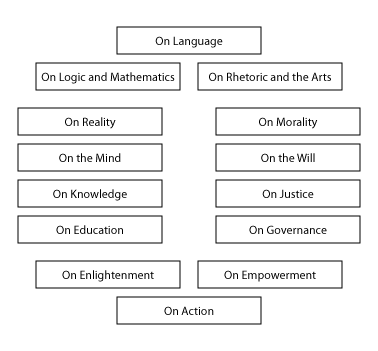

The reason I named the philosophical fields I did is because I think they give a thorough overview of the range of topics philosophy discusses, which all inevitably interrelate with each other. At the most abstract is philosophy of language, and two only slightly less abstract fields that are kind of opposite one another, philosophy of mathematics and philosophy of art. I missed all of those in my formal education and I regret it.

Instead I focused on the two halves of what I'd call core philosophical topics, roughly ontology and epistemology on one hand (about reality and knowledge), and ethics on the other hand (about morality and justice), which I would subdivide into fields analogous to ontology and epistemology (that are also roughly related to utilitarianism and deontology, hence why I emphasized those in particular) but that's not standard practice so I won't go into that here. Metaethics is an especially important part of ethics that ties in closely to philosophy of language, so I recommended that in particular.

Philosophy of mind ties in really closely with ontology and epistemology, and I think free will fits into a similar place regarding ethics because of the connection between free will and moral responsibility. Political philosophy has its obvious connections to ethics as well, being in essence the most important practical application of ethics, and though there doesn't seem to be a single established field that's perfectly analogous to it in relation to ontology and epistemology, I've found significant parallels in both philosophy of education and philosophy of religion, so I recommend those as well.

And lastly, the biggest thing that I overlooked in my formal philosophical education, opposite those abstract fields at the start, is the practical application of philosophy to how to live one's life meaningfully, which Continental schools like existentialism and absurdism address. This topic doesn't seem to have its own name, that I'm aware of, but I colloquially refer to it as "philosophy of life".

The bottom part of this illustration from my philosophy book illustrates the structure I think these fields have to each other:

For these purposes you can ignore everything above Metaphilosophy on that chart, as those are particular views of mine and not philosophical topics (this is actually a chart of the structure of my book, the latter part of which is structured after this same array of topics).

Speaking of which, add Metaphilosophy to my list of fields worth studying. What even is philosophy, what is it trying to do, what constitutes progress at doing that, how can we do it, what does it take to do it, who should do it, and why does it even matter? -

EricH

661

EricH

661

Your brother-in-law's experience is, unfortunately, all too common. As a recently retired programmer I can speak from experience. The ability to be a good programmer is something you either have or do not have. Many of the people I worked side by side with had non-technical backgrounds - musicians, English majors, people from other science disciplines, and even (gasp!) philosophy majors.

That said, a good education can help. I got my graduate degree in CS. Very little of what I learned in school had any direct bearing on the things I encountered in the real world - and with 20/20 hindsight I could have stopped after I got my first job. However the courses I took in data structures, programming languages, math (e.g. set theory) gave me an advantage over my compatriots. -

Mikie

7.3kIf you want to study the subject, which is not necessarily the same as developing a personal philosophy, I strongly recommend studying it historically. Start with the pre-Socratics, then read forward - widely, synoptically and historically. Try and get a feel for the questions that were being grappled with and the historical circumstances in which they arose. Get a feeling for dialectic - that is one of the most elusive aspects of philosophy. Don’t neglect Plato. Find some question that nags at you, then try and find sources that seem to be dealing with the same questions. Learn to feel the questions, not simply verbalise them. — Wayfarer

Mikie

7.3kIf you want to study the subject, which is not necessarily the same as developing a personal philosophy, I strongly recommend studying it historically. Start with the pre-Socratics, then read forward - widely, synoptically and historically. Try and get a feel for the questions that were being grappled with and the historical circumstances in which they arose. Get a feeling for dialectic - that is one of the most elusive aspects of philosophy. Don’t neglect Plato. Find some question that nags at you, then try and find sources that seem to be dealing with the same questions. Learn to feel the questions, not simply verbalise them. — Wayfarer

This is excellent. -

Mikie

7.3k

Mikie

7.3k

If I were to start over, I would start not with what's often called "philosophy" but with learning history, dwelling especially on the Greeks. Read Homer, learn the Greek language.

As far as texts -- start with Parmenides' poem and the fragments of the presocratics. Then Plato and Aristotle. Once you get to Plato and Aristotle, with a decent understanding of the Greek language and the general historical context, then everything else in Western history and philosophy has been basically determined, from the Christian thinkers to Descartes to Kant to Hegel.

Then I would start on the most relevant for modern times (in my view):

Marx, Nietzsche and Heidegger.

Russell, Wittgenstein, and Chomsky. -

A Seagull

615If you were to start from scratch to study the fields of philosophy like epistemology, logic, metaphysics, ethics, philosophy of religion/science/mind etc., not to just know them, but being able to establish knowledge on any ground, to establish a ground you can build your beliefs on, how would your ultimate planning look like?

A Seagull

615If you were to start from scratch to study the fields of philosophy like epistemology, logic, metaphysics, ethics, philosophy of religion/science/mind etc., not to just know them, but being able to establish knowledge on any ground, to establish a ground you can build your beliefs on, how would your ultimate planning look like?

(If you could include details like, what subject you would start with and/or what materials and platforms you would make use of, I would appreciate that)

I welcome well-thought and, strategically smart answers. — Monist

If you really want to "establish a ground you can build your beliefs on", you need to avoid reading ancient philosophers, and indeed most modern ones too. All they do, in the most part, is set up possibilities with hand-waving arguments that amount to little more than religions beliefs; which is fine if you like the religion and can buy into its tenets, but otherwise not.

For example Aristotle's claim that things fall to the ground 'because that is where they want to be' is really quite useless for understanding the physics of gravity. The early philosophers were just scratching at the surface, like an early botanist might start by classifying plants according to the colour of their flowers.

Later philosophers ask questions about whether something 'exists' or is 'right' or 'moral' or 'art'; but they are just playing with words like children play with toy bricks.

No, if you want firm foundations for your beliefs you will need to delve beneath the surface, beneath the level of words, beneath the level of the colours of flowers to the fundamental logic of what an idea is and how one can be created; to the very DNA of philosophy.

To my knowledge there is only one book that deals clearly with this topic and that is "The Pattern Paradigm" https://www.amazon.com/Pattern-Paradigm-Science-Philosophy/dp/1477131728 , of which I am the author.

When you have grasped the fairly straightforward ideas in the book you should have a handle on processes to evaluate other philosophical ideas. Or subsequently you could read the sequel to the book which is entitled: "Making better sense of the world". -

alcontali

1.3kThe ability to be a good programmer is something you either have or do not have. — EricH

alcontali

1.3kThe ability to be a good programmer is something you either have or do not have. — EricH

Agreed.

I have indeed warned my brother-in-law for that problem. Programming requires some kind of talent which is probably innate. It will be up to him to discover if he has it. It is a bit unfortunate that I did not have time to guide him at an earlier age, because in that case, I would have made him discover this much earlier. Still, not everybody in IT needs to be a highly-talented programmer. There are also things like quality assurance, support, product management, consulting, and sales. Even relatively mediocre programming skills are still useful in these ancillary activities. It makes the difference between being just clueless and having some kind of understanding of what it is all about. In that sense, even mediocre programming skills are professionally still useful.

However the courses I took in data structures, programming languages, math (e.g. set theory) gave me an advantage over my compatriots. — EricH

Agreed.

Data structures and algorithms are at the core of the job. Furthermore, it also makes quite a bit of sense to pick up set theory (relational databases) and serious number theory (for cryptography). Unfortunately, they don't teach compiler construction nor mathematical logic.

At the same time, the university seems to be hellbent on getting first-year freshmen to "study" gender studies, political science, and that kind of nonsense. The first year is almost entirely unrelated to computer science. It looks much more like an employment programme for manipulative social-justice warriors to lecture the kids on culturally-Marxist, radical-left ideology.

The universities have become hotbeds of communist agitprop. I find them not only useless but nowadays even outright dangerous.

Welcome to The Philosophy Forum!

Get involved in philosophical discussions about knowledge, truth, language, consciousness, science, politics, religion, logic and mathematics, art, history, and lots more. No ads, no clutter, and very little agreement — just fascinating conversations.

Categories

- Guest category

- Phil. Writing Challenge - June 2025

- The Lounge

- General Philosophy

- Metaphysics & Epistemology

- Philosophy of Mind

- Ethics

- Political Philosophy

- Philosophy of Art

- Logic & Philosophy of Mathematics

- Philosophy of Religion

- Philosophy of Science

- Philosophy of Language

- Interesting Stuff

- Politics and Current Affairs

- Humanities and Social Sciences

- Science and Technology

- Non-English Discussion

- German Discussion

- Spanish Discussion

- Learning Centre

- Resources

- Books and Papers

- Reading groups

- Questions

- Guest Speakers

- David Pearce

- Massimo Pigliucci

- Debates

- Debate Proposals

- Debate Discussion

- Feedback

- Article submissions

- About TPF

- Help

More Discussions

- Other sites we like

- Social media

- Terms of Service

- Sign In

- Created with PlushForums

- © 2026 The Philosophy Forum