-

Gnomon

4.3k

Gnomon

4.3k

I guess I'm not normal, and have no shame, or perhaps I'm just unconventional. But, I have good company. Most of the leading philosophers have been noted, not for using dictionary meanings for old words, but for creating new meanings and new words. This innovation often makes their writings difficult to understand until someone produces a glossary of their technical vocabulary to supplement the common words in Webster's.Normal people would be ashamed to admit they were talking nonsense the whole time, that's what you just said. There is no such definition in English dictionary. Your imaginary language only makes you insane, and it does not answer my point: there is no uncertainty in computer algorithms, do you understand this? — Zelebg

For example, have you ever tried to read A.N. Whitehead's Process and Reality? A century later, you will find "actual occasions of experience', "concresence", and "prehension" in philosophical dictionaries, along with his personal definition of, Creativity : "The fact that endlessly the past is blended with the possible in order to make new units of reality". Does his creative language make him "insane", or merely "imaginative"?

In my previous post, I noted that the whole point of Shannon's Information Theory and its application to computers is precisely because it minimizes uncertainty. But what does that have to do with human consciousness? Do you understand the difference? Materialists assume that computers can eventually emulate human consciousness. But some very smart people say "not so". Yet for both sides, it's an opinion, because computer consciousness (not intelligence) has never been demonstrated. So, you can have your opinion, and I can have mine, without resorting to insulting each other's intelligence. :smile:

Whiteheadian Terminology : http://ppquimby.com/alan/termin.htm

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Alfred_North_Whitehead

Computer Consciousness : http://www.cogsci.uci.edu/~ddhoff/HoffmanComputerConsciousness.pdf -

Zelebg

626

Zelebg

626

I guess I'm not normal, or perhaps I'm just unconventional

You are a baby robot, if you're lucky, otherwise you're logic unit is beyond repair. You're using English words, but not speaking English language. It's called gibberish.

In my previous post, I noted that the whole point of Shannon's Information Theory and its application to computers is precisely because it minimizes uncertainty.

Almost every word is wrong in that sentence. There is no such thing as "Shannon's Information Theory”. There is information entropy in Shannon's theory of communication. It's not applicable to computation, but communication. It does not minimize uncertainty, it defines information as a set of possible messages sent over a noisy channel and defines uncertainty in the context of communication channel capacity.

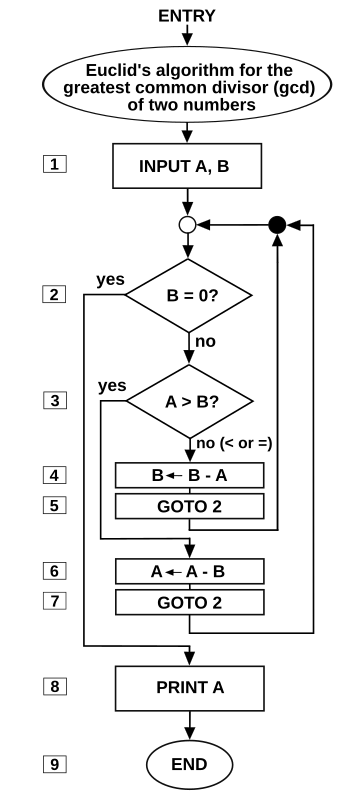

This is how huge your confusion is, like the difference between these two diagrams. One is transfer and communication, the other is algorithm and computation. But to keep insisting on your errors despite all the explanations given and with the internet and English dictionary one click away, that's not just stupid, it's so idiotic it deserves prison punishmet. Go away child robot, shoo, shooo! -

Wayfarer

26.2kThat’s not the Hard Problem of Consciousness at all. That’s just the fact-value distinction. — Pfhorrest

Wayfarer

26.2kThat’s not the Hard Problem of Consciousness at all. That’s just the fact-value distinction. — Pfhorrest

But I think there's a connection between the 'fact-value' distinction, and the 'hard problem', as follows.

The fact-value dichotomy grew out of Hume's observation of 'is and ought'. I won't repeat the famous passage, I assume you're familiar with it. But it is at least an analogy for the larger issue of quantification and measurement, on the one hand, and the importance and role of 'qualia', on the other. 'Qualia' means precisely 'a quality or property as perceived or experienced by a person.' And the hard problem is that 'what it is to be experienced' cannot be objectively or quantifiably described. So the hard problem is actually central to the fact-value distinction.

So, I brought up the fact that in Platonist philosophy, mathematics was important but not of the highest importance. That was accorded to the knowledge of the good, and so on. Whereas, as you say, *anything* can be described in terms of geometric algebra and equations. But the whole point of the hard problem is that, even though such a description appears to be comprehensive, there's something fundamental it doesn't include or describe. And I don't know if you're seeing that. -

Pfhorrest

4.6kAs I see it descriptive (factual) and prescriptive (evaluative) opinions are just different attitudes toward the same kinds of states of affairs, where those states of affairs can be phrased in terms of math as we’ve discussed either way, and the different attitudes can likewise be phrased mathematically as a function of the “program” that is the mind. So phenomenal consciousness isn’t something that needs to be especially invoked for evaluative thinking, even though I’m completely on board with the is-ought distinction (other than Hume’s inference from it that value is non-objective; I think there’s an analogous way that prescriptive value is still objective while remaining completely separate from descriptive fact).

Pfhorrest

4.6kAs I see it descriptive (factual) and prescriptive (evaluative) opinions are just different attitudes toward the same kinds of states of affairs, where those states of affairs can be phrased in terms of math as we’ve discussed either way, and the different attitudes can likewise be phrased mathematically as a function of the “program” that is the mind. So phenomenal consciousness isn’t something that needs to be especially invoked for evaluative thinking, even though I’m completely on board with the is-ought distinction (other than Hume’s inference from it that value is non-objective; I think there’s an analogous way that prescriptive value is still objective while remaining completely separate from descriptive fact).

I understand the connection you see between the two now though so thanks for explaining that. -

Gnomon

4.3k

Gnomon

4.3k

Obviously, we are not talking "in the same way" about our conscious perception of Reality. Philosophers often distinguish between Phenomenal Reality (perception, appearances, maya) and Ultimate Reality (the source of the Information that we interpret as the real world).It doesn't seem to me that we are talking about the same things, or at least in the same way about things, so I don't know how to respond. — Janus

I defined "ultimate or absolute reality" in Platonic terms as "Ideality", which consists of metaphysical Ideas (Forms) instead of physical objects (things). Now, what were you talking about, in your reference to "phenomenal reality' versus "ultimate reality", and "concrete or physical" versus "ideal for us"?

Reality versus Ideality : https://www.quantamagazine.org/the-evolutionary-argument-against-reality-20160421/ -

Janus

18kI defined "ultimate or absolute reality" in Platonic terms as "Ideality", which consists of metaphysical Ideas (Forms) instead of physical objects (things). Now, what were you talking about, in your reference to "phenomenal reality' versus "ultimate reality", and "concrete or physical" versus "ideal for us"? — Gnomon

Janus

18kI defined "ultimate or absolute reality" in Platonic terms as "Ideality", which consists of metaphysical Ideas (Forms) instead of physical objects (things). Now, what were you talking about, in your reference to "phenomenal reality' versus "ultimate reality", and "concrete or physical" versus "ideal for us"? — Gnomon

Yes, and I am saying that defining ultimate reality as either ideality or physicality is to reify notions that derive from our understandings of phenomenality. We cannot think the absolute except apophatically as "neti, neti", or "not this, not this". It is really thought only as a (real) limit to thought and nothing more. So in saying that it is ideal in itself (as opposed to for us) you are succumbing to Kant's "transcendental illusion".

On the other hand, where I diverge from Kant is in saying that the in itself should be thought as being real, insofar as it it is not thought to depend on our thinking at all. Of course the in itself is ideal for us, but we should, in acknowledging that the "map is not the territory", that our models are not reality (but merely a small part of it), think that the in itself in itself is real, whatever it may be. The alternative is to say that whatever we say about it is simply incoherent.

In short, any form of Platonism is a positive reification. -

Zelebg

626Yeah Zelebg that’s not really a tone befitting the forum.

Zelebg

626Yeah Zelebg that’s not really a tone befitting the forum.

I agree, but there is also a little bit of humor in there. -

Gnomon

4.3k

Gnomon

4.3k

That may well be, but a lot of smart people, including pragmatic scientists, not noted for fanciful thinking, argue that Materialism might also be a form of reification. Cognitive researcher Don Hoffman has concluded, after many years of trying to explain Consciousness, that : "our senses are simply a window on this objective reality. Our senses do not, we assume, show us the whole truth of objective reality".In short, any form of Platonism is a positive reification. — Janus

For me, his experiments, arguments and illustrations are compelling. And his alternative to Objective Realism is essentially a 21st century form of Idealism. But of course, it is outside the materialist mainstream, epitomized by Daniel Dennett. Here's a brief synopsis of his recent book.

The Evolutionary Argument Against Reality : https://www.quantamagazine.org/the-evolutionary-argument-against-reality-20160421/

YouTube Video of Hoffman TED Talk : https://youtu.be/oYp5XuGYqqY -

Wayfarer

26.2kWe had a long debate on Hoffman a couple of years back. I concluded his resemblance to 'idealist philosophy' is superficial, his program is fundamentally neo-darwinian and not really connected with philosophy.

Wayfarer

26.2kWe had a long debate on Hoffman a couple of years back. I concluded his resemblance to 'idealist philosophy' is superficial, his program is fundamentally neo-darwinian and not really connected with philosophy.

As I see it descriptive (factual) and prescriptive (evaluative) opinions are just different attitudes toward the same kinds of states of affairs, where those states of affairs can be phrased in terms of math as we’ve discussed either way, and the different attitudes can likewise be phrased mathematically as a function of the “program” that is the mind — Pfhorrest

That description is suggestive of Descartes' notion of 'the new science' which was created on the basis of his discovery of algebraic geometry. It's basic to modern scientific method - that any subject matter can be understood through this kind of universal mathematical analysis. But it omits something of fundamental importance - and that's what the 'hard problem' is seeking to articulate.

This was also anticipated in Thomas Nagel's essay What is it like to be a Bat and this theme is central to many of his later writings.

Chalmer's main antagonist, Daniel Dennett, cannot acknowledge that there is a 'hard problem'. And why not? Well, to me it seems obvious, but Dennett has been writing and publishing for 50 years and is a tenured academic, so it's plainly not obvious to everyone.

There's a stock quote, however, which is relevant to just this issue:

Cartesian anxiety refers to the notion that, since René Descartes posited his influential form of body-mind dualism, Western civilization has suffered from a longing for ontological certainty, or feeling that scientific methods, and especially the study of the world as a thing separate from ourselves, should be able to lead us to a firm and unchanging knowledge of ourselves and the world around us. The term is named after Descartes because of his well-known emphasis on "mind" as different from "body", "self" as different from "other".

Richard J. Bernstein coined the term in his 1983 book Beyond Objectivism and Relativism: Science, Hermeneutics, and Praxis.

This too is a facet of the hard problem of consciousness, in my opinion. -

Gnomon

4.3k

Gnomon

4.3k

I'm sure that was his intention. And he doesn't have much to say about Platonism. In his chapter "Illusory" though, he says, "In Plato's allegory of the cave, prisoners in the cave see flickering shadows cast by objects, but not the objects themselves." But in Hoffman's 21st century update, the cave is replaced by a computer screen, and the shadows by pixelated icons. In both cases, the actual objects (shadow-casters; computer processes) are hidden behind the Wizard's curtain. Presumably, modern cell-phone addicts are the "prisoners".We had a long debate on Hoffman a couple of years back. I concluded his resemblance to 'idealist philosophy' is superficial, his program is fundamentally neo-darwinian and not really connected with philosophy. — Wayfarer

His latest book was published in 2019, so maybe his argument has been refined in the last two years.

https://www.amazon.com/Case-Against-Reality-Evolution-Truth/dp/0393254690 -

prothero

514Obviously there is no consensus agreement on a solution to the so called “hard problem of consciousness”. In fact there is little agreement even on a definition of “consciousness”, “mind”, “experience” or “qualia”. There is also no agreement on which sorts of structures (organisms or systems) possesses any of the above forms of qualia. The exception being “ourselves” our “inner lives” and thus we have first hand knowledge that such a form of experience as consciousness is present in the universe.

prothero

514Obviously there is no consensus agreement on a solution to the so called “hard problem of consciousness”. In fact there is little agreement even on a definition of “consciousness”, “mind”, “experience” or “qualia”. There is also no agreement on which sorts of structures (organisms or systems) possesses any of the above forms of qualia. The exception being “ourselves” our “inner lives” and thus we have first hand knowledge that such a form of experience as consciousness is present in the universe.

Just to clarify, I think consciousness is form of integrated unified experience. I think experience is universal. Mind (a less unified and integrated form of experience) is widespread in nature and “consciousness” is a fairly rare form of mind and experience. I thus fall into the category of panexperientialism or a form of Whiteheadian process philosophy which some classify as a variety of panpsychism.

I think the “problem of consciousness” is a philosophical problem not a scientific problem. The problem arises precisely because we think we should be able to detect and explain “consciousness” using the scientific method. This stems from the dominant materialistic, mechanistic view of nature. In the materialist mechanistic view most of nature is inert, unfeeling, non experiential and psychically inert. From this point of view experience, mind, consciousness, qualia are rare in nature and confined to humans and at most a few higher animals. In the materialist view our scientific, empirical descriptions are complete and accurate descriptions of all aspects of the phenomena which they seek to describe and explain. This strikes me as false for even the most basic of scientific phenomena such as quantum events, entanglement, non locality, and superposition. There are aspects to even these most basic natural phenomena which elude us.

Thus I do not think any purely empirical, mathematical or scientific explanation which is entirely complete and absolute for experience, mind, consciousness or qualia is possible.

This is not a position against the continuing advances of neuroscience, This is not a position against the utility of science in gaining useful and meaningful knowledge of reality. It is a position against the position that science will completely and satisfactorily explain all of nature including our experience.

Now from my philosophical position (process philosophy and panexperientialism), mind and consciousness is not something unexpected for it has not “popped into existence” from inert mindless non experiential matter, for that would truly be a miracle. Instead “occasions of experience” are the fundamental units of nature and we should not talk of “particles” but of “events”

As for Descartes, it was the splitting of nature into two distinct but separate substances (dualism) that began the whole mind body problem (which gives rise to the hard problem of consciousness) in the first place. We are part of nature, our experience is part of nature. We cannot, we should not attempt to explain it away as a purely physical materialist empirical phenomena. Whitehead argues strongly against this “artificial bifurcation of nature” into “nature of awareness and nature as the cause of awareness” the song of the birds, the warmth of the sun, the hardness of chairs and the feel of velvet” these are all part of nature, of reality “ you cannot pick and choose and call quarks real and consciousness an illusion.

). For James, experience is the sole criterion of reality; we live in “a world of pure experience. -

Pfhorrest

4.6kWhiteheadian process philosophy — prothero

Pfhorrest

4.6kWhiteheadian process philosophy — prothero

:up: :clap: :100:

I don’t think there’s necessarily anything nonphysical about that though. See for example Galen Strawson’s “realistic physicalist” panpsychism, and my own essay On Ontology, Being, and the Object of Reality wherein I equate these Whiteheadian occasions of experience to the fundamental particles of quantum physics themselves. -

prothero

514

prothero

514

Whitehead used the term "occasions of experience" as the fundamental units of nature and thus occasions were temporal and had prehensions of the past and of future possibilities. None of these aspects of "occasions of experience" were purely physical or could be explained in purely physical, empirical, mathematical and measurable terms. There are efforts to minimize these aspects of his philosophy by some but reading Whiteheads Concepts of Nature and other works should dispel any notion that he adhered to an entirely materialist, deterministic, physicalist view of nature. On the other hand he thought science was fundamental to philosophy and felt his process philosophy entirely compatible with the "science" of the day assuming one does not equate science with mechanistic determinism. -

prothero

514Ok but that is a unique understanding of the term "physical". Most regard the physical as the empirical, the measurable that which science and not philosophy deals with. I generally say events are fundamental and that events are physical-experiential units and science only deals with the physical aspect of the event. Just an attempt at clarity and more in keeping with the usual understanding and use of terms and Whiteheads terminology.

prothero

514Ok but that is a unique understanding of the term "physical". Most regard the physical as the empirical, the measurable that which science and not philosophy deals with. I generally say events are fundamental and that events are physical-experiential units and science only deals with the physical aspect of the event. Just an attempt at clarity and more in keeping with the usual understanding and use of terms and Whiteheads terminology. -

prothero

514I was looking at your essay, do not have time to read it in detail now but we would seem to have a lot of common ground, philosophically speaking. For instance I do not believe in objects with inherent properties. Objects are repetitive patterns of events and properties are relationships.

prothero

514I was looking at your essay, do not have time to read it in detail now but we would seem to have a lot of common ground, philosophically speaking. For instance I do not believe in objects with inherent properties. Objects are repetitive patterns of events and properties are relationships. -

180 Proof

16.5kP-zombie" is an incoherent construct because it violates Leibniz's Indentity of Indiscernibles without grounds to do so. To wit: an embodied cognition that's physically indiscernible from an ordinary human being cannot not have "phenomenal consciousness" since that is a property of human embodiment (or output of human embodied cognition). A "p-zombie", in other words, is just a five-sided triangle ...— 180 Proof

180 Proof

16.5kP-zombie" is an incoherent construct because it violates Leibniz's Indentity of Indiscernibles without grounds to do so. To wit: an embodied cognition that's physically indiscernible from an ordinary human being cannot not have "phenomenal consciousness" since that is a property of human embodiment (or output of human embodied cognition). A "p-zombie", in other words, is just a five-sided triangle ...— 180 Proof

Why would an entity that has the appearance of a regular human necessarily have phenomenal consciousness?

That's a strong claim. It would require strong evidence. — frank

I neither claimed nor implied anything about "appearances" in relation to "phenomenal consciousness"; I used the concept of embodied cognition to point out that a 'p-zombie' with the same embodied cognition as a human being necessarily has the same phenomenal consciousness as a human being that's the (reflexive) output of human embodied cognitive processes I'm unaware of any explanation to the contrary (re: p-zombie sans phenomenal consciousness), and in all likelihood there isn't one; thus, I don't think the 'p-zombie' construct is conceptually coherent enough to do the thought-experimental work as advertised, namely to reify the illusion of mind-body duality (pace Spinoza et al) viz. qualia, etc aka "the hard problem of ..." -

frank

19kProving mind-body dualism is sort of the opposite of Chalmers' goal. The word "physical" was originally a medical term distinguishing bodily ailments from mental ones. We've long since learned that mental problems often have physical causes, so Cartesian duality was diminished by that. Chalmers pointed out that as scientists investigated functions of consciousness, experience or phenomenal consciousness seemed to remain outside the grasp of scientific language. He believes that inserting experience into the scientific vocabulary as a thing to explain would advance the science of consciousness.

frank

19kProving mind-body dualism is sort of the opposite of Chalmers' goal. The word "physical" was originally a medical term distinguishing bodily ailments from mental ones. We've long since learned that mental problems often have physical causes, so Cartesian duality was diminished by that. Chalmers pointed out that as scientists investigated functions of consciousness, experience or phenomenal consciousness seemed to remain outside the grasp of scientific language. He believes that inserting experience into the scientific vocabulary as a thing to explain would advance the science of consciousness.

I'm reading a book now that attempts to pinpoint when in the evolutionary story phenomenal consciousness appeared in animals. In the introduction, the author talks about Chalmers in order to clarify what the topic of the book is: that it's about experience as opposed to functionality. The fact that this has to be explained is a testament to our legacy of mind-body dualism.

If you get that distinction: function vs accompanying experience, then you don't need the P-zombie as a philosophical tool. You're seeing the difference. As for whether its possible, it's at least metaphysically possible, which just amounts to being able to imagine the p-zombie.

Or are you saying you can't imagine the p-zombie at all? -

sime

1.2kPersonally, what I think the p-zombie thought experiment demonstrates is that my own feelings, imagination and judgements constitute a substantial part of my definition of 'other' minds. For I can, to a limited extent, choose to perceive and imagine those around me to be 'full of spirit and consciousness', or I can perceive and imagine them to be soulless robots or zombies, by perceiving them and thinking about them in different aesthetic ways. (The concept of the presence of another mind and the concept of the absence of another mind refer to different senses)

sime

1.2kPersonally, what I think the p-zombie thought experiment demonstrates is that my own feelings, imagination and judgements constitute a substantial part of my definition of 'other' minds. For I can, to a limited extent, choose to perceive and imagine those around me to be 'full of spirit and consciousness', or I can perceive and imagine them to be soulless robots or zombies, by perceiving them and thinking about them in different aesthetic ways. (The concept of the presence of another mind and the concept of the absence of another mind refer to different senses)

So whilst I agree that 'other minds' exist, I don't agree that they exist independently of my aesthetic judgements of them. For sure, I cannot predict what a person might say and do next, and my predictions concerning that person's behaviour constitutes part of my definition of their mind (or lackof). But their actual behaviour and functionality are not my sole definitional criteria regarding my concept of their mind, for my own feelings and intuitions are very much also a part of my concept of 'other minds'. Hence I cannot be skeptical about the existence of other minds in the sense of truth-by-correspondence, for other minds are partly made true by my construction.

Similarly, suppose that society is divided as to whether tomorrows robots possess consciousness. In my opinion, there is no mind-independent 'matter of fact' as to whether or not robots possess consciousness. Personally, if I feel that a robot is conscious then it is conscious. Any so-called 'objective' definition of robot consciousness will be defined, ultimately, in terms of the social consensus, which one might agree with or might not. I wouldn't regard any such dispute over the existence of robot consciousness to be a dispute over facts 'in themselves' - except for the parts of the dispute that have behavioural implications. -

3017amen

3.1k

3017amen

3.1k

Sure, I'm totally on-board with the mystery associated with conscious existence. Some of the

takeaway's that I'm seeing, as you just suggested is, logical necessity. And then combine that with consciousness being able to break the rules of non-contradiction, then you get logical impossibility.

Conscious existence: Both logically necessary and logically impossible. It is logically necessary for any thought to occur at all; it's logically impossible when we experience it (sensory experience/bivalence-vagueness/physical paradox/phenomenology).

If that's true, what are the implications I wonder... -

prothero

514There are limits to what science can explain.

prothero

514There are limits to what science can explain.

There are limits to what language can describe.

We should explore what those limits might be but philosophy, reason and even logic tell us there are limits. Godels incompleteness and Kants noumena. Consciousness may lie in the boundries. -

3017amen

3.1kGranted, but still raises the question.....why would we care about what we are not? — Mww

3017amen

3.1kGranted, but still raises the question.....why would we care about what we are not? — Mww

Hey Mww, that's an important question. We are hard-wired to care-by default-when doing philosophy. We know that the many philosophical inquiries involving declarative statements (or Kantian propositions and judgements) about our existence involve experience. And in phenomenology, if I experience something that you don't, how then do I know it exists (or vise versa)?

Said another way, how does one know if that experience exists if one doesn't experience it himself? One obvious answer is the objective/subjective truth dichotomy. But all that tells us is that there are different ways of knowing something. It doesn't explain the experience. I think it is another problem of consciousness.

For example, a musician doesn't know what it's like to be a Doctor. And even if he becomes a Doctor, he still cannot experience everything any other Doctor experiences. And the opposite is true in this sense: if a musician claims they had an ineffable experience, who would believe them?

Or, even say, if the layperson hears voices in a pre-dream state (pre-lucid state) that tells him/her to do something extra-ordinary, what should they do; who should they consult to verify its truth value? Anyway, the lists (phenomena) are endless...

I'm thinking you kinda' already know that stuff :) -

Zelebg

626

Zelebg

626

There are limits to what science can explain.

As if there is something else besides science that can explain anything? Science itself doesn't really explain anything either, it only describes the dynamics of the stuff it can measure. But if your conclusions are not based on repeatable measurements, then you can not only not describe anything, you have no reason to believe the thing you're trying to explain even exist in any actual or meaningful way so its existence actually matters.

Welcome to The Philosophy Forum!

Get involved in philosophical discussions about knowledge, truth, language, consciousness, science, politics, religion, logic and mathematics, art, history, and lots more. No ads, no clutter, and very little agreement — just fascinating conversations.

Categories

- Guest category

- Phil. Writing Challenge - June 2025

- The Lounge

- General Philosophy

- Metaphysics & Epistemology

- Philosophy of Mind

- Ethics

- Political Philosophy

- Philosophy of Art

- Logic & Philosophy of Mathematics

- Philosophy of Religion

- Philosophy of Science

- Philosophy of Language

- Interesting Stuff

- Politics and Current Affairs

- Humanities and Social Sciences

- Science and Technology

- Non-English Discussion

- German Discussion

- Spanish Discussion

- Learning Centre

- Resources

- Books and Papers

- Reading groups

- Questions

- Guest Speakers

- David Pearce

- Massimo Pigliucci

- Debates

- Debate Proposals

- Debate Discussion

- Feedback

- Article submissions

- About TPF

- Help

More Discussions

- Other sites we like

- Social media

- Terms of Service

- Sign In

- Created with PlushForums

- © 2026 The Philosophy Forum