-

mcdoodle

1.1kI know that Deleuze considered himself a transcendental empiricist and actually a metaphysician who wanted to provide a metaphysics to support mathematics and science. But this is very far from traditional metaphysics, because it has already accepted that there is a 'master' metaphysics implicit in math and science'; that is it has already accepted materialism. So it is really a rejection of traditional metaphysics; it is only a matter of working out all the details. — John

mcdoodle

1.1kI know that Deleuze considered himself a transcendental empiricist and actually a metaphysician who wanted to provide a metaphysics to support mathematics and science. But this is very far from traditional metaphysics, because it has already accepted that there is a 'master' metaphysics implicit in math and science'; that is it has already accepted materialism. So it is really a rejection of traditional metaphysics; it is only a matter of working out all the details. — John

It does seem puzzling that you don't enjoy arguing with Deleuze, since he seems to have some of the same primary concerns as you but emerges with a different view.

What is common to metaphysics and transcendental philosophy is, above all, this alternative which they both impose on us: either, an undifferentiated ground, a groundlessness, formless nonbeing, or an abyss without differences and without properties, or a supremely indivduated Being and an intensely personalized For. Without this Being or this Form, you will have only chaos... — "Deleuze,

This whole section, in the 'Fifteenth series of singularities', seems like a debate with what you're interested in. -

jkop

969Some of those writers have arguably fueled a kind of anti-intellectualism in the humanities, where the study of canons or the truths of reasoned arguments have been replaced by seditious "discourse" about power, or cliquish bullying because of an assumed absence of decisive conclusions.

jkop

969Some of those writers have arguably fueled a kind of anti-intellectualism in the humanities, where the study of canons or the truths of reasoned arguments have been replaced by seditious "discourse" about power, or cliquish bullying because of an assumed absence of decisive conclusions.

In academic architecture, for instance, Deleuze & Guattari's work attracted interest. But I don't understand what for beside the fact that their approach is reminiscent of artistic work, and seemingly open for arbitrary interpretations. It's easier to make into what you want it to be than, say, the work of APs or the great philosophers of old. -

Janus

17.9kInterestingly, the one-volume anthology of postmodernism I mentioned in the other thread, The Truth about the Truth, has an impassioned essay by Huston Smith saying pretty well exactly that. And, he was included in the volume! — Wayfarer

Janus

17.9kInterestingly, the one-volume anthology of postmodernism I mentioned in the other thread, The Truth about the Truth, has an impassioned essay by Huston Smith saying pretty well exactly that. And, he was included in the volume! — Wayfarer

I can't see any reason to think that the fact that an anthology of Postmodernism that includes an essay agreeing with my characterization of Postmodernism, should lead me to think that my characterization is not correct. That would only follow if you equate the anthology of Postmodernism (anthologies of a movement may certainly contain critiques of that movement) with Postmodernism itself. So, in other words, in critiquing Postmodernism Huston Smith is not himself being a Postmodernist. -

Janus

17.9kInterestingly, the one-volume anthology of postmodernism I mentioned in the other thread, The Truth about the Truth, has an impassioned essay by Huston Smith saying pretty well exactly that. And, he was included in the volume! — Wayfarer

Janus

17.9kInterestingly, the one-volume anthology of postmodernism I mentioned in the other thread, The Truth about the Truth, has an impassioned essay by Huston Smith saying pretty well exactly that. And, he was included in the volume! — Wayfarer

I can't see any reason to think that the fact that an anthology of Postmodernism that includes an essay agreeing with my characterization of Postmodernism, should lead me to think that my characterization is not correct. That would only follow if you equate the anthology of Postmodernism (anthologies of a movement may certainly contain critiques of that movement) with Postmodernism itself. So, in other words, in critiquing Postmodernism Huston Smith is not himself being a Postmodernist.

I have read only snippets of Schuon and Guenon myself, and I do find them more congenial than the PM thinkers.

But then, another approach would be to find some current writer who is a kind of 'post-modern-neo-traditionalist', who draws all those strands together and then critiques the other post modernists on account of their lack of spirituality. There's bound to be one. That would be 'using the strength of the adversary against him'. — Wayfarer

Badiou would be a good example of just what you say; but unfortunately, I do not find him very congenial. Zizek would be another. I read Tarrying with the Negative a few years ago and found it much more congenial. I remember that in that book, for example, he calls for a new critique of the sophistry of the Postmoderns. So, he generalizes there in relation to PM as much as I am.

I think what I see as the most pernicious postmodern thought is the assertion that the subject is nothing more than what has been constructed by social, cultural and discursive forces. PM is thus a kind of mirror image of the materialistic scientific form of determinism. These twin detreminisms deny the freedom and genuine creativity of the person and reduce her to the status of being a mere individual, who is always thought of as being nothing more than a more or less significant part of a more encompassing whole. -

Wayfarer

26.1kBut I think the general point is that 'post-modernism' is not a school of thought (unlike, say, Marxism or German idealism). It may be the case that at this point in history there is a widespread deprecation of the idea of 'the transcendent' - and I agree that this is so - but I don't know if that is characteristic of post-modern philosophy as such.

Wayfarer

26.1kBut I think the general point is that 'post-modernism' is not a school of thought (unlike, say, Marxism or German idealism). It may be the case that at this point in history there is a widespread deprecation of the idea of 'the transcendent' - and I agree that this is so - but I don't know if that is characteristic of post-modern philosophy as such.

(But then, from what desultory reading I have done of the likes of Lacan, Delueze, and the others, I can't see anything that inspires me to study them so probably I should shut up.) -

TheWillowOfDarkness

2.1k

TheWillowOfDarkness

2.1k

I think some are interested the transcendent, but it differs to most instances of transcendent tradtions.

A lot of postmodern interest in the transcendent is about the self and its inability to be captured by language or reduced to part of the world. Postmodernism is characterised by awareness of the self. Myths and values are realised our own. In this respect, I think even its interest in the transcendent is sort of opposed to what held in most transcendent traditions. It sort of views the transcendent as an expression of the world, as something done be existing people, rather than "another realm" which sits above the world. -

Janus

17.9k

Janus

17.9k

I do see what you are saying. I think a common characteristic of PM ( and of most other strains of modern philosophy) consists in the denial of transcendence; which is to say a denial of spirit and genuine freedom. And I think this presumption of immanence has come to pass as a result of the domination of the scientific paradigm. Philosophers are just not taken seriously, for the most part, if they start speaking about anything beyond what is understood as the immanent condition of culturally mediated humanity.

Now I have more sympathy with apo because he is upfront about his interest being confined only to determinate knowledge. He critiques the PoMos for weaving endless skeins of what he sees as 'poetic bullshit'. I actually like some of that poetic bullshit and I think the perspective from immanence is not without its insights. But it is dreadfully limited, as can be seen in the seemingly endless industry of PM thinkers trying to say something significant about humanity without committing any sins of universalism. PoMo is also the fountainhead of political correctness; which I see as being very much a mixed blessing. -

Wayfarer

26.1kIt sort of views the transcendent as an expression of the world, as something done be existing people, rather than "another realm" which sits above the world. — Willow

Wayfarer

26.1kIt sort of views the transcendent as an expression of the world, as something done be existing people, rather than "another realm" which sits above the world. — Willow

I think what I see as the most pernicious postmodern thought is the assertion that the subject is nothing more than what has been constructed by social, cultural and discursive forces. PM is thus a kind of mirror image of the materialistic scientific form of determinism. These twin determinisms deny the freedom and genuine creativity of the person and reduce her to the status of being a mere individual, who is always thought of as being nothing more than a more or less significant part of a more encompassing whole. — John

Agree. So they might criticize 'scientism' and the 'instrumentalisation of reason', and so forth, but their shared intellectual background is still very much a product of 20th century materialism, even if they're purportedly critical of it.

This OP is something you might find interesting - on Jurgen Habermas and the idea of the 'post-secular'. -

Janus

17.9k

Janus

17.9k

I'm coming to think that philosophy should be more to do with the spirit, with life as freely lived, and less to do with endless endeavours to discursively pin down a determinate originary condition. I don't see Deleuze's efforts, in what I have read of Identity and Difference to be anything but the latter. Deleuze treats metaphysics very much as an enquiry into the notion of materiality. Again the truth of immanence, of immanent materiality, is the overarching presupposition behind all his work, at least as I read it. And that would be OK if it weren't the case that that presupposition seems to underlie just about all the work of academic philosophers these days, whatever 'tradition' they identify themselves with. -

TheWillowOfDarkness

2.1k

TheWillowOfDarkness

2.1k

I wouldn't say they are critical of materialism (in the sense of the metaphysical position). They're more critical of the use of the material as a transcendent realm (i.e. scientism, Modernism, the image of the every improving world due to technological advance, etc.,etc.). In the respect, I'd say their more than a product of 20th materialism. I terms of the metaphysical position, they are the most ardent advocates of materialism. They expunge notions of the transcendent realm which had carried over into classical and modern materialism. -

TheWillowOfDarkness

2.1kI do see what you are saying. I think a common characteristic of PM ( and of most other strains of modern philosophy) consists in the denial of transcendence; which is to say a denial of spirit and genuine freedom. And I think this presumption of immanence has come to pass as a result of the domination of the scientific paradigm. Philosophers are just not taken seriously, for the most part, if they start speaking about anything beyond what is understood as the immanent condition of culturally mediated humanity. — John

TheWillowOfDarkness

2.1kI do see what you are saying. I think a common characteristic of PM ( and of most other strains of modern philosophy) consists in the denial of transcendence; which is to say a denial of spirit and genuine freedom. And I think this presumption of immanence has come to pass as a result of the domination of the scientific paradigm. Philosophers are just not taken seriously, for the most part, if they start speaking about anything beyond what is understood as the immanent condition of culturally mediated humanity. — John

Only in appearance, to those who are embedded within traditions of transcendence. Postmodernism argues spirit and freedom are immanent. We cannot not escape our own meaning. Anything we value, any freedom we have, must be within ourselves. The sprit, freedom and meaning was in us all along, even under traditions of transcendence-- it's the believer who lives with hope, who leaves behind despair, who is replete with freedom and sprit. The traditions of transcendence never understood humanity. They assert meaning can only come from the outside, even though it comes from within. A spirited and free human is impossible without themselves as a spirited and free human.

Philosophy which says humanity is irrelevant to their meaning is rejected for good reason. It's contradictory. What it claims to be true cannot be. It's an ignorance of our free, spirited selves. -

Wayfarer

26.1kI have noticed the way 'immanent' is used - as a kind of bulwark against the dreaded 'transcendent', the 'beyond'.

Wayfarer

26.1kI have noticed the way 'immanent' is used - as a kind of bulwark against the dreaded 'transcendent', the 'beyond'.

The traditions of transcendence never understood humanity — Willow

I've never seen any indication from your posts that you have any understanding of what they mean. For instance:

They assert meaning can only come from the outside, even though it comes from within... — Willow

All of the 'traditions of transcendence' say that truth comes from within. I could provide pages of citations in support. The thing which you never seem to grasp is the meaning of the myth (and it is a myth) of 'the fall'. That is, humans are not born with a natural pre-disposition towards inner freedom. The 'natural state' you seem to think is normal, is in fact exceedingly rare. Anyway, this is out of scope for this thread. -

TheWillowOfDarkness

2.1kThis OP is something you might find interesting - on Jurgen Habermas and the idea of the 'post-secular'. — Wayfarer

TheWillowOfDarkness

2.1kThis OP is something you might find interesting - on Jurgen Habermas and the idea of the 'post-secular'. — Wayfarer

That's a good encapsulation of the ignorance of self I'm talking about. The expectation is our spirited selves to come from the outside.

The point can be sharpened: in the context of full-bodied secularism, there would seem to be nothing to pass on to, and therefore no reason for anything like a funeral. — Stanley Fish

Only to those who aren't paying attention to their needs to celebrate, respect and pass on knowledge of the lives of others. Sure both say (the self-ignorant secularist and their religious critics) they have no reason to have a funeral, but this is clearly not true. They have a need to pay respects to the person who was gone.

In this case, both the secularist and the religious critic are expecting the need to come from the outside. They tell a falsehood. A funeral will only matter, they insist, if the outside tells them it's important (e.g. God, Church, etc., etc.). They are turned against themselves and their own needs. -

Janus

17.9k

Janus

17.9k

In itself I agree with some of what I think you are saying here, but I don't agree that is what the PMs argue, or at least if they do argue that, it is not freedom and spirit and as I understand it that they can be talking about, because everything wholly immanent is determined by wholly immanent forces.

Until recently, but really only for the last little while, I have also denied transcendence (under the influence of Hegel, mostly) but what has always troubled me is that immanentist philosophies have no way to understand creativity, freedom and spirit; they say that we must be able to give a discursive account of them otherwise we should not believe they are real. ("The rational is the real", and the rational is what we can measure).

Now I have come to think this is nonsense because the most real thing about us is our experience of creativity, freedom and spirit, and we should give up any notion that it is possible to give a discursively determinant account of them. We can speak of and from them, we can speak creative truths and truths of and from freedom and the spirit; and we can know intuitively very well what they mean, and what their value is; but we cannot subject such accounts to critique or analysis, or in any way objectify them because that will lead either to their destruction or to some form of fundamentalism. -

TheWillowOfDarkness

2.1k

TheWillowOfDarkness

2.1k

They say it comes from within, but they don't believe it. All 'traditions of transcendence' deny people are meaningful-in-themselves. Someone must follow the tradition or else they are heathen nihilists. In each case, meaning is coming for the outside, from God, from scripture, from law and obligation.

The self is the enemy. Everyone one says: "The world means because of God." They do not say: "I mean believing in God." To say the latter would is an offence. It would mean meaning was immanent within them, rather than being granted by a transcendent force. -

Wayfarer

26.1kAll 'traditions of transcendence' deny people are meaningful-in-themselves. Someone must follow the tradition or else they are heathen nihilists. — Willow

Wayfarer

26.1kAll 'traditions of transcendence' deny people are meaningful-in-themselves. Someone must follow the tradition or else they are heathen nihilists. — Willow

You are sadly misinformed about that. I do understand why you think it, but it's not correct. What I think you're commenting on, is the idea in all the spiritual traditions about 'transcending the self' or going beyond ego. My interpretation of that is: going beyond the innate self-seeking behaviours and unhealthy inclinations that we're all born with. That's a very general way of putting it, but you will find the same idea in many different traditions.

Consider the central Christian dogma - that Jesus' sacrifice was on behalf of, and out of love for, mankind. That is not dismissive or condemnatory. Likewise in Mahayana Buddhism, the over-riding ethos is the 'enlightenment of all beings' - the Bodhisattva vow says that 'though sentient beings are numberless, I vow to save all of them'.

It is true that religious and philosophical traditions often betray their original intention - nobody could deny that. But if you're engaged in a philosophical analysis of what they mean, then that is not how they should be judged.

So the self that is the enemy is, if you like, the self that seeks itself, that pleases itself, that is interested in its own pleasures, its own powers, getting its own way. Sure the religions say that is 'the enemy'. -

TheWillowOfDarkness

2.1k

TheWillowOfDarkness

2.1k

Exactly which immanent philosophies say we ought to give such a determination? The idea is incoherent.

Immanence means there is an expression given-- the "divine" is expressed in the material. It's not caused by a force. "Determined by immanent forces" is an oxymoron. Reducing creativity, freedom and spirit to discourse is not required at all. Indeed, it's a contraction to do so. I live my freedom, creative and spirt. It's never just discourse. The "rational" is not the real. Irrational ideas are expressed and have meaning. Logical truth extend beyond what it true of the world. Every expression and state defies reduction to any particular discourse.

Here you analysis working under the idea meaning comes from the outside. Discover the "rational meaning" and you will know what anyone must believe. That's simply not truth. There might be an ethical argument to believe it, but there is no obligation to do do so. People are free to believe an "irrational" (whatever that's supposed to mean. Usually, it just means "what I think you ought to believe" ) position. No discourse can define what people think. They have to live it.

Now I have come to think this is nonsense because the most real thing about us is our experience of creativity, freedom and spirit, and we should give up any notion that it is possible to give a discursively determinant account of them. We can speak of and from them, we can speak creative truths and truths of and from freedom and the spirit; and we can know intuitively very well what they mean, and what their value is; but we cannot subject such accounts to critique or analysis, or in any way objectify them because that will lead either to their destruction or to some form of fundamentalism. — John

This could be a mission statement of post-modernism. Every experience is meaningful, an expression of creativity, freedom an sprit, a value and meaning of an individual. There is no "grounding myth." All experiences are meaningful and any critique or analysis amounts an instance of discursive violence, an attempt to destroy some idea in favour of another. For someone who professes to reject the philosophical worth of post-modernist, you sure talk like one (expecting perhaps the strength of humans and elephants). -

Janus

17.9k

Janus

17.9k

Ah, but there are indeed grounding myths; truths of the spirit that have been handed down to us in the traditions.

Meaning doesn't come from outside at all, but from within. PM generally says meaning comes from culture, that the individual is entirely embedded within culture, and that everything is given by culture. This amounts to saying that the individual absorbs or introjects meaning from culture; but I think this is wrong. The individual absorbs or introjects the means, in the form of education, that enable her to recognize and understand meaning; or to fail to recognize and understand it.

The transcendent meanings of the great works of the spirit within our culture have been leveled down to the rest of the cultural product. According to PoMo, there is no 'high' culture because to say there is would be to posit a hierarchy, a power structure, and hierarchies and power structures are merely arbitrary, after all.

But this is a false conclusion that comes about by objectifying the human spirit. The granting of transcendent (higher spiritual) meaning to the works of culture has come to be seen as merely a function of power and/or discourse. Anybody who says otherwise today will be laughed out of the academé. -

TheWillowOfDarkness

2.1k

TheWillowOfDarkness

2.1k

I'm saying that very argument is what amounts to nihilism and ignorance of the self.

My point is this: people who do not go beyond self-seeking behaviours or unhealthy inclinations are still meaningful. Their lives aren't worthless becasue they have sinned. They've just been unethical. What they need is not "to be saved (the transcendent)" but to alter themselves so life is better for them and people around them. People don't alter their self-seeking behaviour through the transcendent. They do it themselves (which sometimes involves believing in a transcendent force). What is within (a meaningful life and change in behaviour) is misunderstood to be an outside force.

The central Christian dogma is perhaps a prime example of the ignorance I'm talking about. No sacrifice is needed. Sinners have meaningful lives. Jesus doesn't die for love. He dies because God (and some people) don't understand that people who have done wrong still have meaningful lives. He's sent to save us when we don't need saving and to pay for something (all our wrongs) which have no recompense.

So the self that is the enemy is, if you like, the self that seeks itself, that pleases itself, that is interested in its own pleasures, its own powers, getting its own way. Sure the religions say that is 'the enemy'. — Wayfarer

And that's the ignorance. Ethical behaviour is sought by the self, is a power of the self, is an improvement the self, an interested of the self, the self getting its own way and pleases the self. The transcendent tells fibs about overcoming our selfish interests and unhealthy behaviours. In every case, we did that, not some force of another realm. -

Metaphysician Undercover

14.7kI have noticed the way 'immanent' is used - as a kind of bulwark against the dreaded 'transcendent', the 'beyond'. — Wayfarer

Metaphysician Undercover

14.7kI have noticed the way 'immanent' is used - as a kind of bulwark against the dreaded 'transcendent', the 'beyond'. — Wayfarer

The problem within immanence in the strict sense, is that immanent, meaning inherent within, does not conceptualize the 'beyond', or transcendent which is accessible within. The concept of "inherent" ensures that the immanent must always be within that which it is inherent within, never transcending it. So if the immanent is within the material body, it is impossible that it transcends the material body, because the concept of inherent implies that it must always be within that.

All of the 'traditions of transcendence' say that truth comes from within. — Wayfarer

I believe true transcendence is found within. The only way toward transcendence of the material body, and the entire physical, external world, is through the internal. In this way a philosophy of immanence is a step in the right direction, but it doesn't succeed until it finds the route to transcendence through the internal, in this way negating the immanence which leads one there. So the philosophy of immanence is therefore naïve, negating external transcendence, not realizing that the immanent itself will be transcended internally. -

Streetlight

9.1kI think a common characteristic of PM ( and of most other strains of modern philosophy) consists in the denial of transcendence; which is to say a denial of spirit and genuine freedom. And I think this presumption of immanence has come to pass as a result of the domination of the scientific paradigm. — John

Streetlight

9.1kI think a common characteristic of PM ( and of most other strains of modern philosophy) consists in the denial of transcendence; which is to say a denial of spirit and genuine freedom. And I think this presumption of immanence has come to pass as a result of the domination of the scientific paradigm. — John

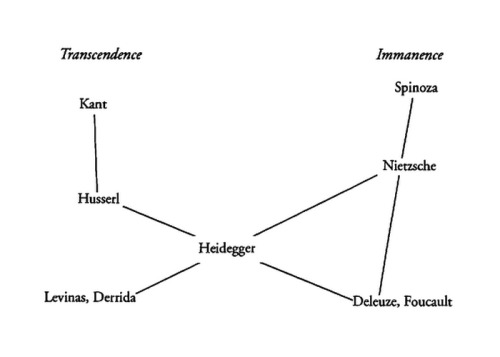

Man, you could have just opened with this, at least this is something vaguely concrete rather than just meta nonsense. Two points to make here. First, there's hardly a blanket 'denial of transcendence' within those thinkers you call postmodern. Without getting into it too much, Giorgio Agamben wrote an essay on Deleuze which, among other things, tracks the various positions of related authors, and he produced the following diagram, which I think is pretty accurate:

(Agamben, "Absolute Immanence", Potentialities)

So it's not exactly like all these thinkers hew to immanence. Secondly, immanence <> fatalism. Personally, one of my original motivations for looking into the tradition of immanence was that I always thought that if transcendence was the guarantor of freedom, then this would be no kind of freedom at all. Any kind of freedom, it seemed to me - and still does - ought to include one within it's circuit; only on an immanent basis could freedom mean anything at all. The two books I'd recommended on this subject are Alicia Juarrero's Dynamics in Action, and Heidi Ravven's The Self Beyond Itself. While I would hardly call both books postmodern (Juarrero comes out of systems theory, Ravven fuses Spinoza with neuroscience), they show quite convincingly what it would mean to configure freedom on an immanent basis. A more properly 'PM' book on this would be Judith Butler's Giving An Account of Oneself, where she shows quite convincingly that any kind of genuine ethical freedom would require that one be subject to forces beyond one's control.

In any case, to think that 'spirit and genuine freedom' are precluded by thinking in terms of immanence is misguided. All this apart from the fact that 'PM' is anything but defined by a commitment to immanence (consider Derrida's puzzlement over Deleuze's notion of immanence, in a piece written after the latter's death: " My first question, I think, would have concerned Artaud, his interpretation of the "body without organ," and the word "immanence" on which he always insisted, in order to make him or let him say something that no doubt still remains secret to us" - "I'll Have to Wander All Alone"). -

TheWillowOfDarkness

2.1k

TheWillowOfDarkness

2.1k

For PM meaning is a culture. Culture is lived, not merely a telling discourse. The question of "comes from culture" is restricted to descriptions of handing down ideas and enforcing one discourse over another .

The transcendent meanings of the great works of the spirit within our culture have been leveled down to the rest of the cultural product. According to PoMo, there is no 'high' culture because to say there is would be to posit a hierarchy, a power structure, and hierarchies and power structures are merely arbitrary. But this is a false conclusion that comes about by objectifying the human spirit. The granting of transcendent (higher spiritual) meaning to the works of culture has come to be seen as merely a function of power and/or discourse. — John

More than that, meaning is a lived experience. It cannot be reduced to merely a function of power or discourse. Things are "arbitrary" because no experience has any more meaning than another. By nature, there is no culture which is better than another. Only in the realm of ethics, hierarchies and power structures can one tradition be preferred to another.

Christian belief and football game are equal in importance precisely because anything else amounts to destruction or fundamentalism. If you want to say your belief is more important, more meaningful or more critical than another, you don't have any choice in discursive violence. You have to say your position is better and more important, that the issue can be reduced to discourse that someone else better believe or follow.

The levelling of culture is a consequence of recognising "grounding myths" are myths. Everything is "high" (or "low") because anything else amounts to reducing another experience to our discourse. It's the truth of spirt lost in recognising we can't reduce meaning to any particular discourse. We know anyone will only be themselves.

(of course, this is what inspires the rabid reactions against PM. Regardless of the ethical worth, any transcendent tradition is revealed to be a falsehood. It hits the traditions where, for believers, it hurts the most: in the idea it's true they've been saved from worthlessness. I mean what's the point of God if it's only a tradition I follow, a set of rules I follow and doesn't make me necessarily more wise than anyone else?). -

Wayfarer

26.1kEthical behaviour is sought by the self, is a power of the self, is an improvement the self, an interested of the self, the self getting its own way and pleases the self.

Wayfarer

26.1kEthical behaviour is sought by the self, is a power of the self, is an improvement the self, an interested of the self, the self getting its own way and pleases the self.

...Christian belief and football game are equal in importance precisely because anything else amounts to destruction or fundamentalism. — TheWillowOfDarkness

You are aptly named, that is all I can say. -

TheWillowOfDarkness

2.1k

TheWillowOfDarkness

2.1k

To the selfish promoters of transcendent beliefs, no doubt.

For people interested in the worth of their practices, as opposed to proclaiming themselves to be better than everyone else, not so much. I don't, for example, have any issue with Christian belief being important to someone. It's not unethical. The world doesn't need Christians to be wiped out. Christianity is still important and valuable.

It just doesn't make someone superior to the football fan. Both cultures are valuable. It's enough for oneself to matter, rather than having to be more meaningful and superior to anyone else. Not that I expect many promoters of transcendent beliefs to grasp that point. It would require too much self-awareness and humility. -

Wayfarer

26.1kI had understood that 'immanence' only ever had meaning as part of a pair, the other part being 'transcendence''; this being an understanding that developed out of theology, namely, that of Spirit being at once 'immanent and transcendent', both 'intimately within' and also 'completely beyond'.

Wayfarer

26.1kI had understood that 'immanence' only ever had meaning as part of a pair, the other part being 'transcendence''; this being an understanding that developed out of theology, namely, that of Spirit being at once 'immanent and transcendent', both 'intimately within' and also 'completely beyond'.

So 'absolute immanence' seems analogous to saying that there is an absolute 'up' or absolute 'left', whereas in reality 'up' only exists in relation to 'down', and 'left' in relation to 'right'.

Googling 'absolute immanence', I get this reference:

Plane of immanence (French: plan d'immanence) is a founding concept in the metaphysics or ontology of French philosopher Gilles Deleuze. Immanence, meaning "existing or remaining within" generally offers a relative opposition to transcendence, that which is beyond or outside

The rest of that wikipedia article, titled Plane of Immanence, seems nonsensical to me, in exactly the way that John means; but then, to its proponents, the kinds of transcendental philosophies that interest he and I seem nonsensical ti them. I think the only real difference is that the postmodernists aren't afraid of their nonsense, but wear it like a badge of honour.; they fashion buildings from it, because, in their eyes, the universe is basically nonsensical anyway. -

Streetlight

9.1kIf anything, the insistence on immanence means that the universe can indeed be made sense of; that sense is engendered within the universe, and we don't have to gape like dead fish out of the water after the unnamable, the unknowable, and the inconceivable.

Streetlight

9.1kIf anything, the insistence on immanence means that the universe can indeed be made sense of; that sense is engendered within the universe, and we don't have to gape like dead fish out of the water after the unnamable, the unknowable, and the inconceivable. -

Janus

17.9k

Janus

17.9k

OK, there are only three Post Moderns in the diagram there and two of them, Deleuze and Foucault, are classed as thinkers of immanence. The other, Derrida is classed as a thinker of transcendence along with Kant and Husserl. First, I wonder whether that should instead be 'transcendentality' (in the sense of thinking the conditions for experience as not themselves being experienced) and in line with the distinction between the transcendental and the transcendent that Kant himself made.

I agree that we must be subject to forces beyond our control; that is certainly obvious insofar as we have bodies. But being subject to forces beyond our control does not equal being utterly controlled by such forces, and I have never yet heard or read a convincing account of how, if we are immanent material beings and nothing but immanent material beings, the kind of (libertarian) freedom in the sense that I understand to be necessary for moral responsibility could be thought to be possible.

So, you've said

and this makes me wonder just how you understand spirit and doubt whether your understanding of it is anything like mine.Just so you know, I understand spirit to be utterly unconditioned and our radical freedom as depending on that. If you understand spirit as some kind of emergent phenomenon, then it will be ineluctably dependent on matter/energy and could never be free in the sense I am thinking of.In any case, to think that 'spirit and genuine freedom' are precluded by thinking in terms of immanence is misguided. — StreetlightX -

Janus

17.9k

Janus

17.9k

It's true that the universe can be made sense of; insofar as rational, discursive accounts and explanations can be given of it. But there remain aspects of human life, many of which are the most important to us, which cannot be explained in this way. The notion that some things must remain mysterious does not offend me or make we want to reject them in accordance with a demand that all must be explainable. On the contrary I feel happy on account of that. -

Janus

17.9kMy point is this: people who do not go beyond self-seeking behaviours or unhealthy inclinations are still meaningful. Their lives aren't worthless because they have sinned. — TheWillowOfDarkness

Janus

17.9kMy point is this: people who do not go beyond self-seeking behaviours or unhealthy inclinations are still meaningful. Their lives aren't worthless because they have sinned. — TheWillowOfDarkness

I haven't anyway said anything to the contrary,

Christian belief and football game are equal in importance precisely because anything else amounts to destruction or fundamentalism. — TheWillowOfDarkness

I couldn't possibly disagree with you more. As I said before there is high culture and low culture and that fact has nothing to do with worldly conditions, power relations, hierarchies or anything like that. What is high and what is low is not determined by any authority, but by the human spirit. We all have our share in the human spirit and we can come to know its truths directly via intuition. Of course that intuition may be clouded by certain ideas; but that is another story. Football is spiritually a low expression; it is an expression of tribalism and aggression; it is a force which divides, not an expression of love. But, don't get me wrong; I am not saying it should be banned or anything.

Welcome to The Philosophy Forum!

Get involved in philosophical discussions about knowledge, truth, language, consciousness, science, politics, religion, logic and mathematics, art, history, and lots more. No ads, no clutter, and very little agreement — just fascinating conversations.

Categories

- Guest category

- Phil. Writing Challenge - June 2025

- The Lounge

- General Philosophy

- Metaphysics & Epistemology

- Philosophy of Mind

- Ethics

- Political Philosophy

- Philosophy of Art

- Logic & Philosophy of Mathematics

- Philosophy of Religion

- Philosophy of Science

- Philosophy of Language

- Interesting Stuff

- Politics and Current Affairs

- Humanities and Social Sciences

- Science and Technology

- Non-English Discussion

- German Discussion

- Spanish Discussion

- Learning Centre

- Resources

- Books and Papers

- Reading groups

- Questions

- Guest Speakers

- David Pearce

- Massimo Pigliucci

- Debates

- Debate Proposals

- Debate Discussion

- Feedback

- Article submissions

- About TPF

- Help

- Other sites we like

- Social media

- Terms of Service

- Sign In

- Created with PlushForums

- © 2026 The Philosophy Forum