-

TheMadFool

13.8kAnatta

In Buddhism, the term anattā or anātman refers to the doctrine of "non-self", that there is no unchanging, permanent self, soul or essence in living beings. — Wikipedia

Basically Buddhism doesn't believe in the existence of a soul. If there's no soul then it follows that without a possesor (soul), nothing can be possessed (not even free will).

Buddhism doesn't have the metaphysical room for Free Will. We're all automatons (in extremis) in a completely deterministic universe.

This seriously undermines Buddhist moral doctrine, after all morality and responsibility require the ability to choose freely.

Am I reading this right?

Perhaps Buddhism beliefs in a physical self (the brain?) and this may be endowed with free will but anatta, as a belief, seems to preclude such an interpretation.

@Wayfarer -

Kym

86It's kind of hard to speak for all Buddhism, since its practice is so fantastically diverse. But it's true that some of the more 'hard-core' schools have views like this.

Kym

86It's kind of hard to speak for all Buddhism, since its practice is so fantastically diverse. But it's true that some of the more 'hard-core' schools have views like this.

Although I don't think they'd let you/me off the hook for personal responsibilty so easily. Those guys are more pragmatic than that. -

Wayfarer

26.1kIt is often said that the Buddha rejects belief in the soul but this has to be interpreted in context. The Latin-Greek-Christian notion of 'soul' is not an exact counterpart for the Hindu 'atman' (which really means 'the self').

Wayfarer

26.1kIt is often said that the Buddha rejects belief in the soul but this has to be interpreted in context. The Latin-Greek-Christian notion of 'soul' is not an exact counterpart for the Hindu 'atman' (which really means 'the self').

It is true that the Buddha doesn't teach that there is a permanent self or soul which is unchanging and constant. Such an idea is compared to a 'post set fast' or 'a solitary mountain peak' which never changes while everything else around it changes. But this was set in the context of a culture in which there was an idea that there was an eternal element within the being, and that the aim of the spiritual life was realising one's identity as this being. The Buddha's attitude was generally: if you say this being exists, where is it? Show it to me! Which, of course, nobody was able to do.

Instead, everything was understood in terms of the chain of dependent origination (pratītyasamutpāda) which analyses experience in terms of the five skandhas and 12 links in the 'chain of causation'. The task is to understand how this actually gives rise to dukkha (suffering or non-satisfaction) due to clinging to what is impermanent as permanent. Understanding this, not just academically but seeing how it operates and freeing oneself from it, is the entire task of the Buddhist discipline.

Furthermore, Buddhists and Vedantins, who were the traditional antagonists in the debate, influenced each other over the course of millenia. Adi Sankara, who was the legendary doyen of Advaita Vedanta, was accused by some of his co-religionists of being too Buddhist! So to really get an appreciation of the subtleties of the debate takes quite a bit of study, as it was conducted in the context of a culture that was vastly different to our own, with a very different conception of what constitutes spiritual liberation, set against the background of the 'eternal round of birth and death'.

Buddhism doesn't have the metaphysical room for Free Will. We're all automatons (in extremis) in a completely deterministic universe. — TheMadFool

This, however, is not accurate. I think it comes from interpreting Buddhism against an implicitly Judeo-Christian frame of reference. In fact many of the early European encounters with Buddhism were characterised by the idea that Buddhism was completely nihilistic, and that the supreme aim of Nirvāṇa was simply the total cessation of being.

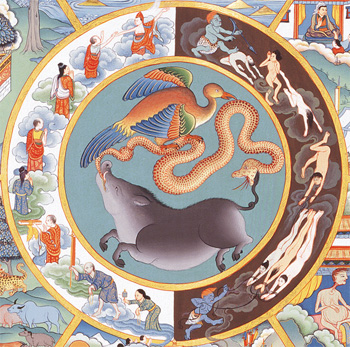

In practice, Buddhism teaches that the experience of beings is largely determined by karma, which is 'the consequences of intentional actions.' It is axiomatic within Buddhism that one's intentional actions give rise to future experiences, (although such an idea is also found, if only germinally, in such Biblical maxims as 'as you sow, so shall you reap'). This is what drives beings through the 'six realms' from one life to another, basically fueled by the 'three poisons' of greed, hatred and stupidity (symbolised iconographically by the pig, snake and chicken):

[Source]

But beings are not totally determined by karma, which would indeed be a fatalistic idea (and something that Buddhists are prone to falling into, in my opinion.) A current Buddhist teacher puts it like this:

For the early Buddhists, karma was non-linear and complex. Other Indian schools believed that karma operated in a simple straight line, with actions from the past influencing the present, and present actions influencing the future. As a result, they saw little room for free will. Buddhists, however, saw that karma acts in multiple feedback loops, with the present moment being shaped both by past and by present actions; present actions shape not only the future but also the present. Furthermore, present actions need not be determined by past actions. In other words, there is free will, although its range is somewhat dictated by the past. The nature of this freedom is symbolized in an image used by the early Buddhists: flowing water. Sometimes the flow from the past is so strong that little can be done except to stand fast, but there are also times when the flow is gentle enough to be diverted in almost any direction.

So, instead of promoting resigned powerlessness, the early Buddhist notion of karma focused on the liberating potential of what the mind is doing with every moment. Who you are — what you come from — is not anywhere near as important as the mind's motives for what it is doing right now. Even though the past may account for many of the inequalities we see in life, our measure as human beings is not the hand we've been dealt, for that hand can change at any moment. We take our own measure by how well we play the hand we've got. If you're suffering, you try not to continue the unskillful mental habits that would keep that particular karmic feedback going. If you see that other people are suffering, and you're in a position to help, you focus not on their karmic past but your karmic opportunity in the present: Someday you may find yourself in the same predicament that they're in now, so here's your opportunity to act in the way you'd like them to act toward you when that day comes.

Karma, Thanissaro Bhikkhu

__//|\\__ -

TheMadFool

13.8kThank you very much. It seems there's something lost in translation. Anyway, I still feel the one aspect that counts here, an eternal essence, that initiates intentional actions and that bears the consequences of such actions, is missing in Buddhism.

The above can be viewed in two ways. One is to see that without any consequences to a self that doesn't exist we really don't have to care about our actions. The other, the better way, I presume, is to continue to act morally despite this fact.

Pragmatic, yes, but there's a fundamental flaw in their philosophy -

Wayfarer

26.1kAnyway, I still feel the one aspect that counts here, an eternal essence, that initiates intentional actions and that bears the consequences of such actions, is missing in Buddhism. — TheMadFool

Wayfarer

26.1kAnyway, I still feel the one aspect that counts here, an eternal essence, that initiates intentional actions and that bears the consequences of such actions, is missing in Buddhism. — TheMadFool

The meaning of 'eternal' is what I suspect is being lost in translation ;-) -

TheMadFool

13.8kThe meaning of 'eternal' is what I suspect is being lost in translation ;-) — Wayfarer

There are so many possibilities. We can imagine an infinite number of theories, especially when we're in the dark. I don't know what to believe.

We've amassed so much knowledge - atoms to the furthest edges of the universe - and yet all of this does nothing to answer questions that have direct bearing on what we all yearn for, a meaningful life.

I want to believe in a soul - something that survives death, the all-purpose meaning killer. Strangely, it isn't something I want. Rather it would help a lot of people - improve their lives by giving them meaning in their lives and a second chance for those who've failed in this life.

Strangely, I like Buddhism for its employment of reason rather than faith. It's a very scientific approach and science has proven itself. However, there's that slim chance that Buddhism is just too rational and that could be a bad thing - paradoxically.

Buddhist sects like Zen seem to be against reason. Look at the Koans of Zen.

What do you think? -

rodrigo

19"The above can be viewed in two ways. One is to see that without any consequences to a self that doesn't exist we really don't have to care about our actions. The other, the better way, I presume, is to continue to act morally despite this fact."

rodrigo

19"The above can be viewed in two ways. One is to see that without any consequences to a self that doesn't exist we really don't have to care about our actions. The other, the better way, I presume, is to continue to act morally despite this fact."

the soul , the inner essence of your being does not plot for the future .... so when a choice is made and consequences evaluated that is not your essence , that is your mind calculating ..... what buddha may be referring to is the simple evolution of your consciousness that indeed will take place .....

suffering is the path to enlightenment and while the body and the mind are the ones in the physical world experiencing the events , it is the consciousness that is the one that rises beyond the minds limited capacity to transmute the suffering into light by acceptance and forgiveness

Welcome to The Philosophy Forum!

Get involved in philosophical discussions about knowledge, truth, language, consciousness, science, politics, religion, logic and mathematics, art, history, and lots more. No ads, no clutter, and very little agreement — just fascinating conversations.

Categories

- Guest category

- Phil. Writing Challenge - June 2025

- The Lounge

- General Philosophy

- Metaphysics & Epistemology

- Philosophy of Mind

- Ethics

- Political Philosophy

- Philosophy of Art

- Logic & Philosophy of Mathematics

- Philosophy of Religion

- Philosophy of Science

- Philosophy of Language

- Interesting Stuff

- Politics and Current Affairs

- Humanities and Social Sciences

- Science and Technology

- Non-English Discussion

- German Discussion

- Spanish Discussion

- Learning Centre

- Resources

- Books and Papers

- Reading groups

- Questions

- Guest Speakers

- David Pearce

- Massimo Pigliucci

- Debates

- Debate Proposals

- Debate Discussion

- Feedback

- Article submissions

- About TPF

- Help

More Discussions

- Other sites we like

- Social media

- Terms of Service

- Sign In

- Created with PlushForums

- © 2026 The Philosophy Forum