-

TheWillowOfDarkness

2.1k

TheWillowOfDarkness

2.1k

The "useful fiction" argument doesn't make sense in the way it's often termed. For physics, the important question is its descriptive power. What makes it "real" is that it accounts for the world, not a particular emprical form-- I mean where is the state of "energy?" Yet, we don't go around saying energy somehow isn't real.

Let's imagine for a moment that atoms weren't a particular state of the world (which is sort of true of the Borh model), would it mean that atomic theory wasn't how the world worked? Not at all. If our objects still behaved in that way, atomic theory would still be expressed by the world; it would be description of how the world really worked, despite the absence of particular atoms which someone could pick-up and hold with atom tweezers. -

Wayfarer

26.2kWhy the interference pattern, then? Why not some other probability distribution? It's highly suggestive that something is interfering. — Marchesk

Wayfarer

26.2kWhy the interference pattern, then? Why not some other probability distribution? It's highly suggestive that something is interfering. — Marchesk

As I understand it, which may be not very well, the probability wave really is a distribution of probabilities - nothing more than that. So it's not actually 'a wave' at all, it simply behaves like a wave - it is 'wave-like' but there really isn't a wave as such, because it doesn't transmit energy or move in a medium, like light waves or water waves. That is why, I think, it is 'rate independent' - the 'wave pattern' really is embedded in the fabric of reality itself, it is of a different order to the physical. That is why the 'nature of the wave function' is the metaphysical question par excellence.

At one time, atoms were just theoretical posits. Anti-realists could have (and maybe did) argue that they were useful fictions for making sense of experiments at the time. But now we can observe them, so obviously they are more than useful fictions. — Marchesk

But the meaning has been changed in the meantime. 'Atom' used to mean 'indivisible particle'. But if you look up the definition of 'atom' now, it is 'the smallest particle of a chemical element that can exist'. But as soon as the atom was shown to be mainly empty space, then I think it ceased to be an atom in the classical sense, i.e. a truly 'indivisible particle'. The idea of 'atoms and the void' could no longer hold. So the atom is no longer the ultimate explanans that is was considered to be by materialism. That is the sense in which physics has undermined materialism. -

andrewk

2.1k

andrewk

2.1k

That's fine. I am sympathetic to everything you report him as saying there, and it's a widely held interpretation. All I was concerned about was whether he was rejecting either the postulates of QM, or results derived from them alone, such as the Heisenberg Uncertainty Relation. It is now clear that he was not. Questions of whether certain things are epistemological or ontological are matters of pure interpretation, since the postulates make no distinction between the two.No, that's not what he was arguing for. Binney stated several times that the probabilistic nature of the value obtained was due to our epistemic uncertainty about the exact quantum state of the measuring device, and not anything fundamental about the state of the particle prior to being measured. A little reading up on HMI reveals that this particular interpretation understands probability to be entirely epistemic (our ignorance or inability to measure everything accurately) and not ontological or fundamental. — Marchesk

In your later post you said Binney said people shouldn't take the QM postulates literally or realistically. I can agree with that too, because it also is about the interpretation, not the calculation. He's not saying we shouldn't believe the predictions they make, which are purely about observations. I do not subscribe to the ontological perspective sometimes known as 'Realism' - but which I think of by the (IMHO) more accurate title 'Materialism'. I lean towards Bohr rather than Einstein. -

Marchesk

4.6kThat is why, I think, it is 'rate independent' - the 'wave pattern' really is embedded in the fabric of reality itself, it is of a different order to the physical. That is why the 'nature of the wave function' is the metaphysical question par excellence. — Wayfarer

Marchesk

4.6kThat is why, I think, it is 'rate independent' - the 'wave pattern' really is embedded in the fabric of reality itself, it is of a different order to the physical. That is why the 'nature of the wave function' is the metaphysical question par excellence. — Wayfarer

This is where I get confused about the Copenhagen interpretation. Is it anti-realist, or is it saying that reality is this non-classical stuff of possibilities that behave like a wave? That seems to be two different interpretations.

The first one leaves questions unanswered. It's the sort of thing Landru of the old forum would have been happy to endorse. Our experiences have a structure. We don't know why, but realism just presents a regress, etc. In terms of the double slit experiment, we don't know why it results in an interference pattern when there isn't a detector on one of the slits. That's just what happens, and physicists developed the math to describe/predict it, because science is merely concerned with prediction (on Landru's account of it).

While the second one, that the world is actually made of probability waves until a measurement (or decoherence) takes place, is puzzling, weird, and almost mystical. The second one is making an ontological claim. -

Wayfarer

26.2kThis is where I get confused about the Copenhagen interpretation. — Marchesk

Wayfarer

26.2kThis is where I get confused about the Copenhagen interpretation. — Marchesk

You're not alone.

I would simply make the point that 'the Copenhagen Interpretation' is not a scientific hypothesis. It is only a description of the kinds of things that Bohr, Heisenberg and Pauli used to say in debates and discussions about interpretation; the term itself wasn't even coined until the 1950's.

that the world is actually made of probability waves until a measurement (or decoherence) takes place, is puzzling, weird, and almost mystical. — Marchesk

During the early days of quantum physics, there was quite a bit of mysticism about. (See Quantum Mysticism - Gone but not Forgotten. And have a read of The Mental Universe.) -

tom

1.5kAlright point taken, but the question is whether the Schrödinger equation is describing the real state of the particle before it's measured, or it just has predictive power as a useful tool, and the reality is something else. Afterall, what the hell is a probability wave supposed to be? — Marchesk

tom

1.5kAlright point taken, but the question is whether the Schrödinger equation is describing the real state of the particle before it's measured, or it just has predictive power as a useful tool, and the reality is something else. Afterall, what the hell is a probability wave supposed to be? — Marchesk

The wavefunction is NOT a probability wave! It's not even a probability amplitude wave! According to Copenhagen, it does not exist. According to Binney it seems to not exist either.

According to the only known REALIST interpretation that agrees with QM, the wavefunction is an element of reality, but exactly what? The mathematical properties of the wavefunction correspond to features of reality, and the only way to make sense of this is to accept that the wavefunction represents a branching (and occasionally recombining) world-density function.

It turns out that under realist QM - i.e. the sort where the only dynamics is UNITARY evolution of the wavefunction, then probability is not part of the theory, it is not required. That is not to say that probability is not an extremely useful MODEL in most circumstances.

In context of Binney and HMI, if the reality would be our epistemic uncertainty about the complex state of the measuring device having a large influence on the particle it's detecting. — Marchesk

For Binney, quantum mechanics is not a physical theory. If you ask me, everyone else in the discussion section of the video you posted was embarrassed into silence. It was a car-crash. At least he does not believe in objective propability - i.e. his version of QM is a stochastic theory of human ignorance.

If MWI is the case, then probability wave is a description of other worlds. Or it could be pilot waves guiding the particle. But then again, perhaps reality is a jumble of possibilities when we're not looking? Question is why does measurement make it classical? Why is our lived experience mostly classical? — Marchesk

For systems of more than one particle, QM takes place explicitly in Hilbert space - not in the space-time. This should at least indicate that the idea of "probability waves" flying around is wrong. In fact, under the Heisenberg picture, the wavefunction is stationary - it does not change - and all dynamics is contained within the observables! Why does no one talk about observables flying around?

If MWI is the case, then probability wave is a description of other worlds. Or it could be pilot waves guiding the particle. But then again, perhaps reality is a jumble of possibilities when we're not looking? Question is why does measurement make it classical? Why is our lived experience mostly classical? — Marchesk

Decoherence. -

tom

1.5kThis is where I get confused about the Copenhagen interpretation. Is it anti-realist, or is it saying that reality is this non-classical stuff of possibilities that behave like a wave? That seems to be two different interpretations. — Marchesk

tom

1.5kThis is where I get confused about the Copenhagen interpretation. Is it anti-realist, or is it saying that reality is this non-classical stuff of possibilities that behave like a wave? That seems to be two different interpretations. — Marchesk

The Copenhagen is anti-realist; it is a purely epistemic theory. The "Standard" interpretation, taught at most (American) universities calls itself Copenhagen, but it's not. It is based on the famous book by von Neumann "The Mathematical Foundations of Quantum Mechanics". That interpretation definitely has a realist feel to it. In British universities, the treatment tends to be closer to Dirac, which again feels realist.

Quantum mechanics is quite hard, and is made more so by obfuscators like Binney. You aren't going to be asked for an essay on ontology or epistemology in your final exam, but you are going to need to shut up and calculate.

In terms of the double slit experiment, we don't know why it results in an interference pattern when there isn't a detector on one of the slits. — Marchesk

Yes we do! -

Marchesk

4.6kYes we do — tom

Marchesk

4.6kYes we do — tom

Feynman said that nobody understands, assuming that wasn't taken out of context, but I always understood him to be saying that nobody knows why the double slit and other experiments give the results they do. How many nuances to the various interpretations are there, btw?

For systems of more than one particle, QM takes place explicitly in Hilbert space - not in the space-time. — tom

What is Hilbert space, and what makes it any more real than probability waves? And I don't mean what is the math, I mean what does the math represent? -

Marchesk

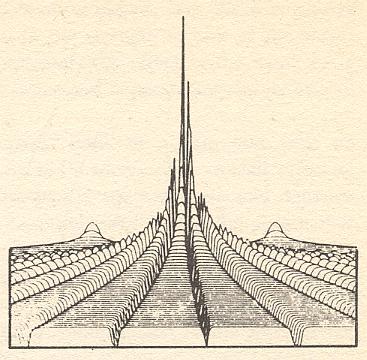

4.6kFor those who like the pilot wave theories: — Agustino

Marchesk

4.6kFor those who like the pilot wave theories: — Agustino

Actually, that video was pretty amazing! Maybe there really is something to pilot waves. I didn't know there was a classical system that produced similar results for the double slit experiment. And you can see it happening! Definitely helps visualize de Broglie's interpretation.

I guess the bouncing silicon oil drops creating the standing waves is a classical pilot wave system. -

Metaphysician Undercover

14.9kThis one touches upon an important issue. When we say there is a unique ket for each physical state, we are saying that the relation between physical states and kets is a 'function', as that word is technically understood in mathematics. That means that any physical state can only have one associated ket. It does not, however mean that two different physical states cannot have the same ket, and that's where your point about complete descriptions comes in. For any two different states to necessarily have different kets would imply that the ket is a complete description of the physical state. The postulates of QM do not claim that the ket is a complete description. Claims of completeness or otherwise of the kets are either interpretations of QM, or part of theories that seek to extend QM. They are not part of core QM. — andrewk

Metaphysician Undercover

14.9kThis one touches upon an important issue. When we say there is a unique ket for each physical state, we are saying that the relation between physical states and kets is a 'function', as that word is technically understood in mathematics. That means that any physical state can only have one associated ket. It does not, however mean that two different physical states cannot have the same ket, and that's where your point about complete descriptions comes in. For any two different states to necessarily have different kets would imply that the ket is a complete description of the physical state. The postulates of QM do not claim that the ket is a complete description. Claims of completeness or otherwise of the kets are either interpretations of QM, or part of theories that seek to extend QM. They are not part of core QM. — andrewk

I think I understand what you say here, the ket describes the state of the system in such a way which allows that two distinct states have the very same ket. Therefore the ket cannot be a complete description of the state. To make an example in a very general way, the apple and the orange may both be represented by the same mathematical symbol (1), but this does not mean that these two things are the same, it means that the mathematical way of describing them, as each being one, is an incomplete description.

I didn't completely grasp all of your question, but I answered it as best I could. Let me know if I left anything out. — andrewk

The other issue I was trying to bring to your attention is the nature of the time-energy uncertainty relation. Some may say that this uncertainty relation is just a form of expression of the Heisenberg uncertainty, but it is impossible that these are the same uncertainty because time and energy are not canonically conjugate variables.

Time cannot be brought into the ket in the same way as the other variables, so it becomes a parameter. I believe that this is because time, t, is not an observable, and any relation between t and an observable is the relation of a function. I understand that Von Neumann wanted to make time an operator, most likely to maintain consistency with relativity. Apparently he tried having a t for each particle of the system, and also tried a designated t particle, to no avail. Consequently, field mathematics was utilized instead, to account for this difficulty with t. But field theory produces what I believe to be absurd conclusions, such as symmetries and anti-matter.

So the question is what is the relationship between these two distinct uncertainties, the time-energy uncertainty, and the Heisenberg uncertainty. Where exactly do these uncertainties lie, concealed within the mathematics, and what happens when they are brought to bear upon each other? The Heisenberg uncertainty is well documented and I assume the best expression of it is found in the Schrodinger equation. I assume that the time-energy uncertainty must be concealed within field theory. There's a Soviet paper, by Mandelshtam and Tamm, (Journal of Physics, vol. 9 no. 4, 1945), entitled "The uncertainty relation between energy and time in non relativistic quantum mechanics" which is quite descriptive. Also, there's a paper I haven't yet read, by D. A. Arbatsky (2006) entitled "The certainty principle". If you have the time, see if you can evaluate the mathematics of this "certainty principle". Intuitively, I feel that there is a mistake in Arbatsky's claim that the Heisenberg uncertainty is more fundamental than the time-energy uncertainty, and this might result in the falsification of Arbatsky's claim that the certainty principle is more fundamental than the uncertainty principle. but this may depend on one's approach (one's prior assumptions). -

Rich

3.2kActually, that video was pretty amazing! Maybe there really is something to pilot waves. I didn't know there was a classical system that produced similar results for the double slit experiment. And you can see it happening! Definitely helps visualize de Broglie's interpretation.

Rich

3.2kActually, that video was pretty amazing! Maybe there really is something to pilot waves. I didn't know there was a classical system that produced similar results for the double slit experiment. And you can see it happening! Definitely helps visualize de Broglie's interpretation.

I guess the bouncing silicon oil drops creating the standing waves is a classical pilot wave system. — Marchesk

I believe that it was Bohm in one of his writings who suggested that there really wasn't a particle in the De Broglie-Bohm Interpretation, but rather what we witnessing is a wave perturbation. This would make the theories realistic properties quite straightforward to understand from a realistic, conceptual point of view. The impulse behind this wave perturbation is something to ponder which is why Bohm suggested that his model leaves open the possibility for creative impulses in his Implicate Order. The video was quite interesting.

-

tom

1.5kWhat is Hilbert space, and what makes it any more real than probability waves? And I don't mean what is the math, I mean what does the math represent? — Marchesk

tom

1.5kWhat is Hilbert space, and what makes it any more real than probability waves? And I don't mean what is the math, I mean what does the math represent? — Marchesk

Would it surprise you to learn that classical mechanics can also be formulated in terms of wavefunctions on Hilbert space?

No one thinks there are probability waves flying around in classical physics. What exists are rocks, chairs, planets ... and they aren't in Hilbert space either. -

andrewk

2.1k

andrewk

2.1k

Quite right, they are not the same uncertainty and, as far as I know, Heisenberg had nothing to do with the time-energy relation. The explanation of the relation in Shankar is just a hand wave, not a mathematical derivation. When I looked it up in my hard copy I found some scathing comments I had written about it at the time I read it, which is probably why I dismissed it from my mind and didn't remember it.The other issue I was trying to bring to your attention is the nature of the time-energy uncertainty relation. Some may say that this uncertainty relation is just a form of expression of the Heisenberg uncertainty, but it is impossible that these are the same uncertainty because time and energy are not canonically conjugate variables. — Metaphysician Undercover

I have not studied the time-energy relation and so do not know whether it can be deduced from the bare postulates. My pencilled comments on the text indicate a suspicion that other, non-core, assumptions are being used. But because the Shankar presentation is so lacking in detail, one cannot be sure of that.

According to wikipedia, those are the people that invented that relation, and published it in that paper. One would have to read the paper to find out what assumptions it uses, and I have not read it.So the question is what is the relationship between these two distinct uncertainties, the time-energy uncertainty, and the Heisenberg uncertainty. .......... There's a Soviet paper, by Mandelshtam and Tamm, (Journal of Physics, vol. 9 no. 4, 1945), entitled "The uncertainty relation between energy and time in non relativistic quantum mechanics" which is quite descriptive. — Metaphysician Undercover

I suspect the time-energy uncertainty relation is not very important anyway since (1) it only appears in a short appendix to the Shankar chapter on uncertainty relations and (2) while the wiki article on Heisenberg highlights his uncertainty principle (for complementary observables) as the discovery for which he is best known, the energy-time relation is not directly mentioned in the articles on its discoverers, Mandelshtam and Tamm. -

Metaphysician Undercover

14.9kI wouldn't be so quick to dismiss the importance of the time-energy uncertainty relation. It is not well understood, and perhaps that's why Shankar does a bad job covering it. But it is derived directly from the Fourier transform due to the nature of the frequency - time conjugate variables. It was not discovered or invented by Mandelshtam and Tamm, as it was already understood by people like Heisenberg, Von Neumann, and Pauli. Dirac apparently had produced a formal representation in 1926.

Metaphysician Undercover

14.9kI wouldn't be so quick to dismiss the importance of the time-energy uncertainty relation. It is not well understood, and perhaps that's why Shankar does a bad job covering it. But it is derived directly from the Fourier transform due to the nature of the frequency - time conjugate variables. It was not discovered or invented by Mandelshtam and Tamm, as it was already understood by people like Heisenberg, Von Neumann, and Pauli. Dirac apparently had produced a formal representation in 1926.

As I understand it, the time-energy uncertainty is closely related to the local/non-local dichotomy. Von Neumann could not bring time into the QM equations as he desired, as an operator, a conjugate variable of the Hamiltonian operator for energy. Others, like Pauli saw this right away as an impossibility, time is not observable, and they were willing to accept the consequences So time became a parameter, it is therefore outside the system. This leaves an uncertainty relation between the quantum system and its environment which determines time. That allows for relations between the internal and the external of the system which are not constrained by the laws of physics. -

Numi Who

19

Numi Who

19

That is not a question for philosophy, but for science - unbeknownst to most philosophers, the divination of reality has been passed on to science (for around 400 years now).

What a philosopher would ask is a question that science will never address, but desperately needs an answer to (so it will not be so easily commandeered by mindless megalomaniacs), a question that we all need an adequate answer to, the Greatest of the Great Questions of Life: that of "Why Bother?"

Without an adequate answer to that Greatest of the Great Questions of Life (for you must admit, you must answer that question before you even begin to address the others), all will crumble in uncertainty. (I have the answer, by the way) (and no - it is not a smart-ass answer. so don't go there).

To save myself from having to respond later, the answer is "Because consciousness is a good thing" (think of the alternative). This answer, by the way, also reveals the Ultimate Value of Life - Higher Consciousness (which humans have, but do not adequately use yet), which gives us the Ultimate Goal of Life (securing the Ultimate Value, naturally). In our case, it would be 'securing higher consciousness in a harsh and deadly universe". Now that we have an Ultimate Goal, we have the Ultimate Arbiter in determining good from evil (their being goal-driven), and with that ability, we can build worthwhile individual lives (with a clue) and relevant civilizations (finally). -

Metaphysician Undercover

14.9kWhat a philosopher would ask is a question that science will never address, but desperately needs an answer to (so it will not be so easily commandeered by mindless megalomaniacs), a question that we all need an adequate answer to, the Greatest of the Great Questions of Life: that of "Why Bother?"

Metaphysician Undercover

14.9kWhat a philosopher would ask is a question that science will never address, but desperately needs an answer to (so it will not be so easily commandeered by mindless megalomaniacs), a question that we all need an adequate answer to, the Greatest of the Great Questions of Life: that of "Why Bother?"

Without an adequate answer to that Greatest of the Great Questions of Life (for you must admit, you must answer that question before you even begin to address the others), all will crumble in uncertainty. (I have the answer, by the way) (and no - it is not a smart-ass answer. so don't go there). — Numi Who

Why must this question be answered first? If the philosophical nature is simply "the desire to know", then why can't we direct our inquisition toward anything we want? Philosophy begins in wonder, and we can wonder about anything without having any notion as to why we are wondering about this. What makes you believe that this particular question, "Why Bother", must be answered before we ask all those other questions?

Welcome to The Philosophy Forum!

Get involved in philosophical discussions about knowledge, truth, language, consciousness, science, politics, religion, logic and mathematics, art, history, and lots more. No ads, no clutter, and very little agreement — just fascinating conversations.

Categories

- Guest category

- Phil. Writing Challenge - June 2025

- The Lounge

- General Philosophy

- Metaphysics & Epistemology

- Philosophy of Mind

- Ethics

- Political Philosophy

- Philosophy of Art

- Logic & Philosophy of Mathematics

- Philosophy of Religion

- Philosophy of Science

- Philosophy of Language

- Interesting Stuff

- Politics and Current Affairs

- Humanities and Social Sciences

- Science and Technology

- Non-English Discussion

- German Discussion

- Spanish Discussion

- Learning Centre

- Resources

- Books and Papers

- Reading groups

- Questions

- Guest Speakers

- David Pearce

- Massimo Pigliucci

- Debates

- Debate Proposals

- Debate Discussion

- Feedback

- Article submissions

- About TPF

- Help

More Discussions

- Other sites we like

- Social media

- Terms of Service

- Sign In

- Created with PlushForums

- © 2026 The Philosophy Forum