-

Wheatley

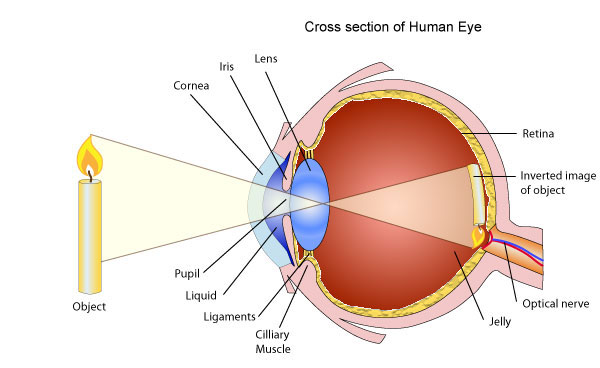

2.3kWhen light enters your eyes the light is refracted in such a way that it projects an inverted image on the retina:

Wheatley

2.3kWhen light enters your eyes the light is refracted in such a way that it projects an inverted image on the retina:

I don't know if this means we actually see the world upside down. It all depends on how vision works, which isn't the concern and scope of this OP. What interests me is, supposing that we do see the world upside down (hypothetically or not), would it make any difference?

One thing to note is that if I saw everything upside down I would also see myself and my bodily movements upside down. How would this perceptual impairment effect my life? Suppose I decide to move my hand upward? Let's break it down:

- The world will remain the way it is, positioned correctly.

- I see the world as inverted.

- I see my actions as inverted. (after all, I am part of the world)

I decide to move my hand up, however what I believe is up is actually down. As a result, I'm really attempting to move my hand down.

The thing is, attempting to lower my hand in a world that is inverted from how I see it would have the opposite effect and make it rise.

The end result is me lifting my hand. I wanted to lift my hand and I actually lifted my hand in the real world, even though my judgments were all wrong. Whether or not I see the world inverted or not, I get the same results. How incredible is that? -

Terrapin Station

13.8kI think it's worth critically examining just how we supposedly know this, too.

Terrapin Station

13.8kI think it's worth critically examining just how we supposedly know this, too.

For one, the idea of light moving at straight, clean angles and intersecting at a point, where the interaction with the eye seems to be posited as if the eye were more or less a vacuum for light "rays" to travel in seems a bit ridiculous(ly oversimplified).

We still don't even have a really good model of what light is. It doesn't seem to be quite a particle or quite a wave but something that exhibits properties of one or the other in various situations. -

Marchesk

4.6kWe still don't even have a really good model of what light is. It doesn't seem to be quite a particle or quite a wave but something that exhibits properties of one or the other in various situations. — Terrapin Station

Marchesk

4.6kWe still don't even have a really good model of what light is. It doesn't seem to be quite a particle or quite a wave but something that exhibits properties of one or the other in various situations. — Terrapin Station

Same applies to matter. Maybe it's all some kind of field. -

Banno

30.6kThat part of the process of seeing involves the image being inverted does not imply that we see the world upside down.

Banno

30.6kThat part of the process of seeing involves the image being inverted does not imply that we see the world upside down.

We see the world the right way up.

@Terrapin Station we don't need QM here. Stop over-thinking. -

TheWillowOfDarkness

2.1k

TheWillowOfDarkness

2.1k

I imagine if the reflection on the retina was right way up, we might see the world inverted, assuming reflection is working like mirrors. -

Streetlight

9.1k

Streetlight

9.1k

As Banno noted, this exact thing - wearing inverted glasses over a prolonged period of time - has been a well known scientific experiment, and there's been alot written about the results. The first most striking result is that after a while, one simply gets used to it - your perception of the world - after interacting with it (this is important) - simply rights itself eventually, and you see just like you did without the glasses. Moreover, once you take the glasses off, your vision has to once again readjust - it has to 'correct' itself once again.

The second striking result is the phenomenology of it: wearing the inverted glasses doesn't simply flip the world up-side down, at first. Rather, it disrupts sight altogether - it leads to a kind of initial experiential blindness. Quoting one of the studies: "During visual fixations, every movement of my head gives rise to the most unexpected and peculiar transformations of objects in the visual field. The most familiar forms dissolve and reintegrate in ways never before seen. At time, parts of figures run together the spaces disappearing from view: at other times, they run apart, as if intent on deceiving the viewer." Or as Alva Noe puts it, the result is not (initially) simply seeing differently, but failing to see.

This eventually changes, as the glasses wearer interacts with the world around themselves, and quite literally learns to see again. As Noe reports, there are three stages to this: the first stage is a confusing one: things on the left look as though they are on the right, even though things feel as though they are on the left. Next, things on the left still look as thought they are on the right, but now they also feel that they are on the right. Last, everything aligns: what's on the left both looks like it's on the left, and feels like it's on the left. 'Normal' vision is restored. Importantly all this happens only if one interacts with the world around themselves, moving, holding, touching, reaching out, etc.

The biggest takeway from all this is that visual perception is bodily and interactive in the extreme: sight is not just a question of 'images' but of literally interacting with a world which gives rise to sight. Perception is a 'complex', a conjunction between what is seen, what is felt, how one interacts with the world, and not just 'what' one sees. In short - anti-realism is a bunch of bullshit, and any elementary study of perception will confirm this. -

Wayfarer

26.1kI recall reading about an experiment in cognitive science in which kittens were raised in an environment where there were no vertical obstacles, only horizontal ones. After some time, when vertical objects were introduced into the environment, the kittens would collide with them, until their brains adjusted to their presence.

Wayfarer

26.1kI recall reading about an experiment in cognitive science in which kittens were raised in an environment where there were no vertical obstacles, only horizontal ones. After some time, when vertical objects were introduced into the environment, the kittens would collide with them, until their brains adjusted to their presence.

Actually there were a couple of other anecdotes that I read of around this time, one of which the story of a pygmy chieftain, who was taken, by some anthropologists, up on top of a mountain look-out. This individual had spent his entire life in dense forest where everything was more or less within arms' reach. Once at this mountain lookout, the pygmy didn't seem to react badly, but after a while he was seen squatting down and reaching forwards as if to pick something up off the ground in front of him. The anthropologists theorised that he was actually trying to pick up a distant herd of wildebeest that could be seen on the distant plains beneath; they got the impression that he thought they were insects right at his feet. Because, of course, he had no 'wiring' for 'distant plains beneath', not ever having experienced such a vista.

What this all points to, is the role of the mind and brain in 'constructing' or synthesising experience; it shows up how what we instinctively categorise as real is in some fundamental way dependent on a constructive act of synthesis. -

frank

18.9kPerception is a 'complex', a conjunction between what is seen, what is felt, how one interacts with the world, and not just 'what' one sees. — StreetlightX

frank

18.9kPerception is a 'complex', a conjunction between what is seen, what is felt, how one interacts with the world, and not just 'what' one sees. — StreetlightX

It also emphasizes the far reaching ability of the brain to manipulate sensory input (course we already knew that.) -

Deleted User

-15Perception is a 'complex', a conjunction between what is seen, what is felt, how one interacts with the world, and not just 'what' one sees. In short - anti-realism is a bunch of bullshit, and any elementary study of perception will confirm this. — StreetlightX

Deleted User

-15Perception is a 'complex', a conjunction between what is seen, what is felt, how one interacts with the world, and not just 'what' one sees. In short - anti-realism is a bunch of bullshit, and any elementary study of perception will confirm this. — StreetlightX

The vision-inversion experiment proves only that:

1) A vision-inversion-experience takes some time for the mind to process and integrate.

2) The experience of motion and interaction within a visually inverted frame of reference is crucial to processing and integrating a vision-inversion-experience.

It has nothing conclusive to say about realism and anti-realism. You've assumed your conclusion. Your hammer has turned it into a nail. -

Streetlight

9.1kYou've assumed your conclusion — ZzzoneiroCosm

Streetlight

9.1kYou've assumed your conclusion — ZzzoneiroCosm

Says the post that shunts everything into the artificially constructed vocabulary of 'experience' from the get-go. -

Deleted User

-15Says the post that shunts everything into the artificially constructed vocabulary of 'experience' from the get-go. — StreetlightX

Deleted User

-15Says the post that shunts everything into the artificially constructed vocabulary of 'experience' from the get-go. — StreetlightX

...To demonstrate that a vision-inversion experiment is easily assimilated to an experience-centric dialect and metaphysics.

Note my conclusion: A vision-inversion experiment has nothing to say about realism and anti-realism. -

Streetlight

9.1k...To demonstrate that a vision-inversion experiment is easily assimilated to an experience-centric dialect and metaphysics. — ZzzoneiroCosm

Streetlight

9.1k...To demonstrate that a vision-inversion experiment is easily assimilated to an experience-centric dialect and metaphysics. — ZzzoneiroCosm

Sure, if you beg the question, anything is possible. -

Deleted User

-15Sure, if you beg the question, anything is possible. — StreetlightX

Deleted User

-15Sure, if you beg the question, anything is possible. — StreetlightX

Because you have chosen your camp you attack my counterpoise as a kind of begging. This is the hammer speaking. My intention is more charitable: I mean to demonstrate that a vision-inversion experiment is as content with Berkeleyan idealism as with the directest of realisms.

Again: A vision-inversion experiment has nothing to say about realism and anti-realism. -

Streetlight

9.1kIn a way you're right - one of the implications is a kind of short-circuiting of the whole debate: perception, as a matter of interaction, is neither realist nor anti-realist, but something else altogether. Of course, one could simply tack on, as you have done, a rather vulgar reading of the whole thing in terms of experience. But this says more about those who like to do such tacking on, than anything about the experiment.

Streetlight

9.1kIn a way you're right - one of the implications is a kind of short-circuiting of the whole debate: perception, as a matter of interaction, is neither realist nor anti-realist, but something else altogether. Of course, one could simply tack on, as you have done, a rather vulgar reading of the whole thing in terms of experience. But this says more about those who like to do such tacking on, than anything about the experiment. -

frank

18.9kAre you saying perception is equivalent to interactions? A case could be made for that, but the experiments mentioned only show that processing is set up by interactions. Likewise anatomy changes when a toddler tries to walk. Walking isn't equivalent to the processes that brought it about, though.

frank

18.9kAre you saying perception is equivalent to interactions? A case could be made for that, but the experiments mentioned only show that processing is set up by interactions. Likewise anatomy changes when a toddler tries to walk. Walking isn't equivalent to the processes that brought it about, though.

Welcome to The Philosophy Forum!

Get involved in philosophical discussions about knowledge, truth, language, consciousness, science, politics, religion, logic and mathematics, art, history, and lots more. No ads, no clutter, and very little agreement — just fascinating conversations.

Categories

- Guest category

- Phil. Writing Challenge - June 2025

- The Lounge

- General Philosophy

- Metaphysics & Epistemology

- Philosophy of Mind

- Ethics

- Political Philosophy

- Philosophy of Art

- Logic & Philosophy of Mathematics

- Philosophy of Religion

- Philosophy of Science

- Philosophy of Language

- Interesting Stuff

- Politics and Current Affairs

- Humanities and Social Sciences

- Science and Technology

- Non-English Discussion

- German Discussion

- Spanish Discussion

- Learning Centre

- Resources

- Books and Papers

- Reading groups

- Questions

- Guest Speakers

- David Pearce

- Massimo Pigliucci

- Debates

- Debate Proposals

- Debate Discussion

- Feedback

- Article submissions

- About TPF

- Help

More Discussions

- Have you guys ever regretted falling down the rabbit hole seeing how deep it can get?

- When you go down on a knee what are you going down for?

- Is platonism pre-supposed when writing down formal theories?

- Danger of a Break Down of Social Justice

- New here- i need my brain to stop racing. Any thoughts on slowing down?

- Other sites we like

- Social media

- Terms of Service

- Sign In

- Created with PlushForums

- © 2026 The Philosophy Forum