-

Terrapin Station

13.8kSo, how does one know that insects perceive UV light? From what reference point is that given? How do we know the structure of atoms? Has anyone ever seen a single atom? — Noah Te Stroete

Terrapin Station

13.8kSo, how does one know that insects perceive UV light? From what reference point is that given? How do we know the structure of atoms? Has anyone ever seen a single atom? — Noah Te Stroete

Do you think that I'm denying theoretical knowledge for some reason? -

RegularGuy

2.6kI’m trying to figure out how you justify your belief that reality is directly apprehended.

RegularGuy

2.6kI’m trying to figure out how you justify your belief that reality is directly apprehended. -

Michael

16.8kBut is it anti-realist? — Noah Te Stroete

Michael

16.8kBut is it anti-realist? — Noah Te Stroete

Yes. See Kant's transcendental idealism and Putnam's internal realism.

Also see Plantinga's How to be an Anti-Realist:

...one speaks of realism or anti-realism with respect to a given area or subject matter: universals, say, or the past, or other minds, or sets, or micro-entities in physics. And in one use of these terms, the realist is just a person who argues that there really are such things as universals, or other minds, or propositions. In this way of using the term, a realist with respect to inferred entities in science thinks there really are such things as the elementary particles-atoms, electrons, quarks and the like--endorsed by contemporary physics; he adds that they have pretty much the properties contemporary science says they have. And of course an anti-realist with respect to inferred entities denies these things. Call this sort of anti-realist an 'existential anti-realist'.

...

But there is another brand of anti-realism, one that is substantially a modern, post-Kantian phenomenon. The Kantian anti-realist doesn't deny the existence of an alleged range of objects; he holds instead that objects of the sort in question are not ontologically independent of persons and their ways of thinking and behaving. Kant didn't deny, of course, that there are such things as horses, houses, planets and stars; nor did he deny that these things are material objects. Instead his characteristic claim is that their existence and fundamental structure have been conferred upon them by the conceptual activity of persons. According to Kant, the whole phenomenal world receives its fundamental structure from the constituting activities of mind ... let's call it 'creative anti-realism'.

...

So there are at least two kinds of anti-realism: creative and existential. Each, furthermore, can be restricted to a certain domain, or taken globally (although global existential anti-realism--the view that nothing whatever exists-has never been popular). With respect to a given domain, one can be either a creative anti-realist or an existential anti-realist.

...

One might be an existential anti-realist with respect to unobservable entities such as quarks, but an existential realist with respect to the ordinary middlesized object of everyday life. Or one might be an existential realist with respect to the former and a creative anti-realist with respect to the latter.

The last sentence is key. One can believe that things like the fundamental entities of our best scientific models or otherwise unknowable noumena have a mind-independent existence but that the everyday objects of perception do not (as these latter things are not reducible to the former). It's a type of idealism (objects of perception are mind-dependent) that isn't solipsistic (things other than oneself exist). -

Wayfarer

26.1kThe Kantian anti-realist doesn't deny the existence of an alleged range of objects; he holds instead that objects of the sort in question are not ontologically independent of persons and their ways of thinking and behaving. Kant didn't deny, of course, that there are such things as horses, houses, planets and stars; nor did he deny that these things are material objects. Instead his characteristic claim is that their existence and fundamental structure have been conferred upon them by the conceptual activity of persons. According to Kant, the whole phenomenal world receives its fundamental structure from the constituting activities of mind ... let's call it 'creative anti-realism'.

Wayfarer

26.1kThe Kantian anti-realist doesn't deny the existence of an alleged range of objects; he holds instead that objects of the sort in question are not ontologically independent of persons and their ways of thinking and behaving. Kant didn't deny, of course, that there are such things as horses, houses, planets and stars; nor did he deny that these things are material objects. Instead his characteristic claim is that their existence and fundamental structure have been conferred upon them by the conceptual activity of persons. According to Kant, the whole phenomenal world receives its fundamental structure from the constituting activities of mind ... let's call it 'creative anti-realism'.

:ok: -

Dfpolis

1.3kOkay, so first, you're applying a concept that you've constructed. Do you agree with that? It's not as if you're perceiving concepts or anything like that. A concept is something you do, personally, in response to things. — Terrapin Station

Dfpolis

1.3kOkay, so first, you're applying a concept that you've constructed. Do you agree with that? It's not as if you're perceiving concepts or anything like that. A concept is something you do, personally, in response to things. — Terrapin Station

No, I do not construct concepts in experiencing and abstracting. I find them latent in my sensory representation. So, I actualize prior intelligibility, converting a potential concept into an actual concept. I do this by focusing on a particular aspect of what is presented. If I constructed concepts as you suggest, there would be no basis for applying the concept to its next instance.

Now, you might say that I partially construct the concept, but then how do I come to the other part? And, on what basis do I apply the construct to a new instance in which (on your view) it is not latent?

No, I do not perceive concepts, I perceive the content of concepts. A concept or an idea is not a thing, not something that can be sensed. It is an activity. The concept <duck> is me thinking of ducks. It is the thinking about something that converts sensory data about it into a concept. That is what it means for awareness to actualize prior intelligibility.

It is well-known that we can do complex tasks (driving, bicycling, playing music) automatically, without awareness. So there is a sensory level of interaction with reality in which intelligibility is never actualized because we act without awareness -- "lost in thought."

Secondly, you can perceive a duck and not think anything like the name "duck," or think of the concept of a duck, or any sort of mental content per se period, right? — Terrapin Station

That is what I just said. Still, when we focus awareness on this or that aspect of our sensory stream, that is actualizing its intelligibility, even it there is no naming of what we are attending to.

I don't see what that would have to do with the word "understand(ing)" or "intelligibility." Those seem like misleading words to use there. (At least relative to their conventional senses.) — Terrapin Station

I agree that "knowing" is better than "understanding," still they are related in an essential way. It is by examining the structure of what we are acquainted with that we come to understand it in the sense of making judgements about it. So, to understand requires that we first actualize the intelligibility of what we seek to understand, then parse it by fixing on its various aspects or notes of intelligibility, and then recombine what we have parsed out in judgements that yield propositional knowledge. -

Dfpolis

1.3kDoes anyone here really understand one another? — Noah Te Stroete

Dfpolis

1.3kDoes anyone here really understand one another? — Noah Te Stroete

I freely admit to having some difficulty understanding @Terrapin Station. I also have difficulty seeing any socially redeeming value in transcendental idealism.

I think Terrapin Station is saying that there is a real way something IS from a particular spatial temporal reference point, and how that thing is from that particular point is knowable by thinking about a theoretical model of that reference point in relation to the object. That doesn’t require a perceiver but a thought grounded in theory. Theory comes about from experience from perceiving and about thinking about the objects of perception, which have an actual way they are from a spatial temporal reference point. Is that right? — Noah Te Stroete

The problem with this account is that when you say, "That doesn’t require a perceiver but a thought grounded in theory," it makes theory prior to our encountering what we are theorizing about. Knowing is a subject-object relation. There can be no knowing without a known object and a knowing subject. So, while one can theorize about things one does not know to exist, to know a thing requires encountering it -- interacting with it. Our informative interactions with physical objects are called sensations or perceptions. So, unless we sense something (directly or indirectly) it makes no sense to theorize about it.

Of course we do view things from a certain perspective. That is one reason why all human knowledge is a projection (a dimensionally diminished map) of reality. Another reason is that our culture may incline us to attend to some aspects of experience in preference to others, and to project the results into a culturally-received conceptual space.

What exactly then is your position re Kant about what is inherent to the mind as laid out in Critique of Pure Reason? Is space and time at least partially constructed in the mind? Or are space and time inherent to the physical world ONLY? — Noah Te Stroete

I have grave difficulties with the notion of imposed "forms of reason." If we automatically imposed the forms of space and time, alternate views of space and time (at least with respect to empirical reality) would be literally unthinkable. The same applies to time-sequenced (aka accidental) causality, which many interpreters of quantum theory seriously question. I think Aristotle is dead on, and anticipates the special and general theories of relativity, when he defines time as "the measure of change according to before and after." Change is real, and time is a way of measuring change. So, time has a foundation in reality (change), but is also a way that humans interact with physical reality (by measuring it). Relativity shows us how the measuring process can affect our measures of time and space. -

leo

882Sure, but I'm not at all endorsing representationalism, idealism, etc. Those require theoretical moves just like any other stance does. That was the point. — Terrapin Station

leo

882Sure, but I'm not at all endorsing representationalism, idealism, etc. Those require theoretical moves just like any other stance does. That was the point. — Terrapin Station

I think Terrapin Station is saying that there is a real way something IS from a particular spatial temporal reference point, and how that thing is from that particular point is knowable

— Noah Te Stroete

That's all correct. To finish the above, it's knowable, for one, from perception, which isn't theoretical. But in cases where perception isn't possible, sure, then we have to do something theoretical. — Terrapin Station

Okay. So now my question would be, if anything anyone experiences is reality from a particular reference point, how do you ever get to a distinction between reality and hallucination? -

Mww

5.4kI also have difficulty seeing any socially redeeming value in transcendental idealism. — Dfpolis

Mww

5.4kI also have difficulty seeing any socially redeeming value in transcendental idealism. — Dfpolis

As well you should. The first critique, from which the philosophy of transcendental idealism is born and raised, has nothing to do with social redemption or its value. For socially redeeming value, which is more anthropology or empirical psychology than speculative metaphysics proper, one needs examine the second and third critiques. -

Dfpolis

1.3kThe latter being the unconscious or autonomic condition, the former being the conscious or attentive condition? — Mww

Dfpolis

1.3kThe latter being the unconscious or autonomic condition, the former being the conscious or attentive condition? — Mww

Yes

But you said some data is available to awareness but some data processing is not. Seems like this is two separate and distinct dynamics, only one of which would seem to have any continuity with the treatise on Realism and experience. What bearing does unavailable data processing have on the topic? — Mww

There are many examples that have to do with sensory processing. For example, the eye does edge enhancement. The brain converts ciliar motions in the cochlea into representations of tone, loudness and so on. These processes occur without any trace of awareness but are essential to the sensory representations presented to awareness.

I call an object’s modification of my neural state the appearance of an object; it is not yet represented by a synthesis of intuition and concept. So yes, we agree perceptual duality is a non-starter. — Mww

The same insights can be articulated in various ways.

Radiance of action....ok....just another theoretical tenet. — Mww

I'd say it is an empirical finding -- one taken from physics and which forms the basis of field theories.

Not clear about partial identity. What would be full identity? — Mww

It is partial because the subject is not identically the object. We are not the apple we perceive. The apple's action on our nervous system is only a small fraction of what an apple is capable of doing and our neural representation of the apple is only a minor part of us.

If the apple’s modification of a neural state is identically a representation of the apple, is that the same as saying the apple is experienced? — Mww

Yes, if you mean sensory experience. Awareness may subsequently convert sensory experience to knowledge (intellectual experience). Or, possibly, the sensation will be ignored or handled automatically.

Does this experience correlate one-to-one with knowledge? — Mww

There are different kinds of knowledge. First is knowledge as acquaintance, which begins with awareness of a sensory presentation. Once we are aware of an object, we nay fix on various aspects or notes of intelligibility, dividing it up mentally. Then, in judgement we recombine these notes to come to propositional knowledge.

There is correspondence, but it is not one-to-one. Some experiences are more fully elaborated than others -- yielding more concepts and more judgements.

Where did “apple” come from? Doesn’t look like this theory has any place for conceptual naming. — Mww

Where we see that many objects have the same intelligibility (evoke the same concept) we come to understand that the concept has universal extension, i.e, that it is potentially applicable to many particulars. (Applicability is based on the fact that each instance can properly evoke the applied concept.) If we wish to communicate this, we assign the concept <apple> a name such as "apple" or "pomme." In doing this we abstract from the kinds of differences you mention. Because of the irrelevance of such differences to the central concept, Aristotelians call them "accidents."

If one holds with the idea that any object of perception is nothing to us until we add our own elements to it, by means of synthesis, rather than take away from its totality those <8 thoughts you spoke about, there is no need for confusing the abstraction for the object. While there is still a chance for confusion, it arises from judgement alone, as an aspect of reason. — Mww

There is never a need for confusion. Still, it is all to common.

I agree that we have individual associations with objects, but I don't see them as part of the core concept. Also I agree that errors occur in judgements. -

jorndoe

4.2k(emphasis mine)

jorndoe

4.2k(emphasis mine)

A transcendental idealist says that some things are empirical experience and other things are mental constructs. Sense data are by their nature from outside reality. Space and time and frames of reference are mental constructs or inside projected outside. Did I get that right, @Mww? — Noah Te StroetePretty much covers it, yep. — Mww

@Mww, would you say that mentioned mental constructs are part of the same larger world (outside reality) as the experienced?

If so, then @Galuchat's inquiry seems to indicate a need to differentiate among hallucination and perception, yes?

Are hallucinations real? — GaluchatYes. They are real experiences potentially informing us of the reality of some neurological disorder. — Dfpolis

I suppose, like synesthesia and phantom limbs perhaps.

That seems to converge on some sort of ordinary realism, surely not mental monism (idealism).

The mere existence of hallucinations and perception is not really in question (or so it seems to me), yet they're different, and the difference would then be the perceived (which includes other people). -

Mww

5.4kBecause it is true

Mww

5.4kBecause it is true

, we arrive at:The same insights can be articulated in various ways. — Dfpolis

......

....becomes reason may subsequently convert sensory experience to knowledge.Awareness may subsequently convert sensory experience to knowledge — Dfpolis

.....

.....becomes knowledge *of* and knowledge *that*.First is knowledge as acquaintance, (...) (and) There is correspondence — Dfpolis

....

...becomes the ground for the viability of the ten Aristotelian and twelve Kantian categories, as universally extendable conceptions.we come to understand that the concept has universal extension — Dfpolis

....

....becomes due to the fact these differences are at least logically irrelevant, insofar as no identifying property of an apple may ever be logically applied to the identity of a horse, we are permitted to disregard the totality of properties or attributes of objects of perception, and merely assign concepts to them a priori as understanding thinks belongs to them necessarily. As such, accidents are circumvented.Because of the irrelevance of such differences to the central concept — Dfpolis

———————

This was a little tougher to unpack:

I agree that we have individual associations with objects, but I don't see them as part of the core concept. — Dfpolis

I think you mean we each understand what an object is by the way we associate extant experience to it, but those experiences are not seen as part of the core concept of the object. If that is correct, or at least close, then I would agree, because the “core concept” of an object would give to us the thing as it is in itself a posteriori, by presupposing apprehension of the unconditioned (assuming a “core concept” is some sort of ultimate cognitive reduction), which my philosophy will never allow.

Ever onward...... -

Harry Hindu

5.9k

Harry Hindu

5.9k

I'm not so sure. Is time and space an illusion - a product of how our minds parse the world?Of course. I was talking about whether reference points are inherent in the world absent minds or not. — Noah Te Stroete

Time is just relative change. If the mind is a process, then it functions at a particular frequency of change relative to the frequency of change in other processes, like trees and oranges. How those things appear will depend on how fast or slow the frequency of change is relative to how slow or fast the brain processes the information about them. So, fast processes will appear as a blur, or may be missed completely, while very slow processes will appear as stable, persistent "objects" in space. Think about how reptiles need heat to warm their bodies and improve their response times. When a lizard is lethargic, its brain is functioning at a slower frequency relative to the rest of the environment. It can't respond to fast changes quickly enough. When it warms up, it can. Our brains have similar states.

Well, yes those are changing properties of oranges and orange trees, only one of which has to do with location - "falling". The others are properties of the orange that do not change when you change your location, like "ripeness". Ripeness is a property of the orange that changes. Ripeness does not change with location. Thought is a property of me that changes. Ripeness and thoughts are properties (that are not spatial properties) of different things in the world that interact and produce taste and smell of ripe or rotten oranges. The taste and smell of oranges would be about that interaction between ripe oranges and gustatory and olfactory sensory organs.How would you think that the properties of an orange (or anything else) don't change? You wouldn't be able to have orange trees flowering, some of the flowers turning into fruit, the fruit developing, eventually ripening, falling, decomposing, etc. — Terrapin Station -

Harry Hindu

5.9k

Harry Hindu

5.9k

Well, I'm an indirect realist, so I would agree that we don't directly apprehend, but we do apprehend. How would we be able to even posit and confirm the existence of atoms if not for some observation? It seems to me that we don't just look, we interpret. It's just a matter of interpreting correctly what it is you are seeing (a mass of atoms). But we don't see atoms. We see light, which is why a mass of atoms looks bent when submerged within another mass of atoms. If something is lost in perception it seems to me that we would never know and not be able to posit the existence of those things or properties.Perception is about the things causing the perception. One doesn’t directly apprehend the thing in itself. One perceives things. A lot is lost in perception (for example, do you perceive atoms when looking at a chair?), and the mind constructs a “story” about the object that is perceived but not directly apprehended. — Noah Te Stroete

Then how can we get at causes by observing only effects? Were the tree rings in a tree stump caused by how the tree grows throughout the year independent of some perception of the tree growing? How is it that we can determine the age of the tree by the number of tree rings if it wasn't for how the tree grows independent of my perception of its growth?“Reference” implies a referring to something. Can something refer to something else without conceptualization or perception? That is what I can’t figure out. I’m leaning towards no. — Noah Te Stroete

I didn't use the word, "representation". I used the term, "about". "About" as a preposition is defined by the Cambridge dictionary as "on the subject of; connected with".Do you not understand the difference between causation and subject matter/representation? When I talk to you my speech is caused by my body (lungs, vocal chords, mouth, etc.) but those words aren’t (always) about my body. When I flip a switch on a wall it turns on a light but that light isn’t a representation of me flipping the switch.

There can be an external world that stimulates whatever it is that I am in such a way that it elicits in me a certain kind of experience without it then following that such an experience is representative of or about that external world cause.

The tree we experience isn’t the atoms and photons that cause the experience. It’s a coherent, non-solipsistic, anti-realist account of trees. — Michael

https://dictionary.cambridge.org/us/dictionary/english/about

Any effect is temporally connected with prior causes.

Those sounds coming from your mouth are the effect of all the causes that lead up to you making sounds with your mouth, which goes all the way back to the Big Bang. If the Big Bang never occurred, would you be here making sounds with your mouth? If Big Bangs are a necessary cause for the subsequent existence of bodies that make sounds (determinism), then you making sounds is an indication that a Big Bang happened sometime in the past. Every effect carries information about every cause leading up to it. It's just a matter of which particular chain of causes that you want to talk about or focus on in any particular moment. Hearing you speak informs me that you have a mouth, what your native language is, your knowledge of your native language, as well as the ideas in your head. Which particular cause did you want me to focus on? When we use language it is generally understood that we are meant to focus on the ideas in someone's head.

If there was no tree or light, how is it that you would have a visual experience of a tree? -

Terrapin Station

13.8kNo, I do not construct concepts in experiencing and abstracting. I find them latent in my sensory representation. So, I actualize prior intelligibility, converting a potential concept into an actual concept. I do this by focusing on a particular aspect of what is presented. If I constructed concepts as you suggest, there would be no basis for applying the concept to its next instance. — Dfpolis

Terrapin Station

13.8kNo, I do not construct concepts in experiencing and abstracting. I find them latent in my sensory representation. So, I actualize prior intelligibility, converting a potential concept into an actual concept. I do this by focusing on a particular aspect of what is presented. If I constructed concepts as you suggest, there would be no basis for applying the concept to its next instance. — Dfpolis

So we don't agree on what concepts are or how they work.

Also, I haven't the faintest what "find them latent in my sensory representation" or "actualize prior intelligibility" would refer to. To me that just sounds like words randomly strung together.

Re "no basis for applying the concept in a consequent instance"--you construct the concept, and you have a memory.

Now, you might say that I partially construct the concept, but then how do I come to the other part? — Dfpolis

"The other part"? I have no idea what that's referring to.

And, on what basis do I apply the construct to a new instance in which (on your view) it is not latent? — Dfpolis

We could start at the beginning, with how infants do this, and we could start in a scenario where there either are or are not other people (using language) in the environment, but doing any of that would be pretty laborious in this setting, and it's not really necessary. Let's say that you already have a lot of concepts on hand--like beetles and wings and eyes and so on, because you're an adult, and let's say that you're an entomologist working in the Amazon. You discover an odd individual insect. It has only one wing but can fly, and it squirts some sort of gunk out of its eyes, and so on. So you wonder if you've discovered a new species. You provisionally call it coleoptera monocornu goopojo (a silly name that doesn't follow scientific conventions well, but that's what you initially come up with)--we'll call it cmg for short. You look for other single-winged, eye-goop-shooting beetles in the area, and you find some that aren't exactly alike--some have one large but one very stunted wing, some shoot green eye goop instead of blue, etc., but per your concept, you decide to call any beetle with more or less one wing, that flies, and that shoots colored goop out of its eyes a cmg.

Later, you might decide that there's an important difference between the green and blue goop shooters, or between the beetles that have no trace of a second wing and those that have stunted second wings. And then you'd revise your concept--either adding subgroups to cmg's, or only considering some cmg's while others would have a new concept-name applied, to accomodate what you consider to be important differences (while ignoring the differences that you don't consider to be important). That's how you apply a concept in further instances.

This is already too long, so I'm going to leave it there for now. We could continue with the rest of the post I'm responding to later. -

Mww

5.4kwould you say that mentioned mental constructs are part of the same larger world (outside reality) as the experienced?

Mww

5.4kwould you say that mentioned mental constructs are part of the same larger world (outside reality) as the experienced?

If so, then Galuchat's inquiry seems to indicate a need to differentiate among hallucination and perception, yes? — jorndoe

Hmmmm........

The mentioned mental constructs, re: space, time, points of reference, are not of the same larger world as the experienced; they are the necessary conditions for it. To say that because rational agents holding with these conditions are part of the larger outside world, then by association so too are his conceptions, is a categorical error. To attribute to rationality that which properly belongs to physicality is to ask for a common cause for distinctly different effects.

It can be said there is sometimes a need to distinguish hallucination from perception, yes. All optical illusions are hallucinations from empirical misrepresentation, but some hallucinations are purely logical faults given by understanding itself. In the former, judgement usually reconciles the defect and its cognition is modified, but in the latter judgement often condones it and is thereby cognized as being the case.

But......disclaimer.....I don’t like psychology, so........grain of salt and all that. -

Terrapin Station

13.8kI’m trying to figure out how you justify your belief that reality is directly apprehended. — Noah Te Stroete

Terrapin Station

13.8kI’m trying to figure out how you justify your belief that reality is directly apprehended. — Noah Te Stroete

The simple answer is that in order to have the belief that reality can NOT be directly perceived (insofar as its perceived, re what's perceived, etc.--in other words, no one is saying that you're "perceiving everything about everything"), you'd need evidence that x is not really like F, whereas your initial perception was that x was like F. But to have evidence of that that counts against the initial evidence, we'd have to be able to accurately perceive the way something really is, contra our mistake, which means that we can at least sometimes directly, correctly perceive things.

This also includes the notion that we can directly, correctly perceive things like eyes and ears and brains and machines that we hook up to them, so that we'd have some accurate info about how they work. -

Terrapin Station

13.8kIf you're positing that stuff exists that's separate from your mind, and that isn't just others' minds, you're a realist.

Terrapin Station

13.8kIf you're positing that stuff exists that's separate from your mind, and that isn't just others' minds, you're a realist. -

Terrapin Station

13.8kOkay. So now my question would be, if anything anyone experiences is reality from a particular reference point, how do you ever get to a distinction between reality and hallucination? — leo

Terrapin Station

13.8kOkay. So now my question would be, if anything anyone experiences is reality from a particular reference point, how do you ever get to a distinction between reality and hallucination? — leo

So first, hallucinations and illusions are real hallucinations and illusions. (Where we're not using "real" in the traditional manner to refer to something objective or that exists extramentally.) But we can know that there are no real pink elephants in someone's apartment when they're hallucinating a pink elephant in their apartment, because other people can see that there are no pink elephants, we can tell this via instruments, as well, and we know a lot about how matter behaves and can behave, what's required for there to be an elephant in an apartment, and we also know a lot about how brains work, including how they work on LSD (if that should be the case in this instance), etc.

We know, however, that hallucinating a pink elephant is really what the world is like when someone's brain is in a particular state, perhaps when it's triggered by certain other visual phenomena, etc. -

jorndoe

4.2kThe mentioned mental constructs, re: space, time, points of reference, are not of the same larger world as the experienced; they are the necessary conditions for it. — Mww

jorndoe

4.2kThe mentioned mental constructs, re: space, time, points of reference, are not of the same larger world as the experienced; they are the necessary conditions for it. — Mww

An ontological hierarchy of sorts?

The perceived world depends existentially on spacetime, which in turn depends existentially on the perceiving mind?

All optical illusions are hallucinations from empirical misrepresentation, but some hallucinations are purely logical faults given by understanding itself. In the former, judgement usually reconciles the defect and its cognition is modified, [...] — Mww

I'd just say that swimmers in water look different than swimmers out of water.

(At least we do have some understanding of what's going on with refraction, reflection and such.)

-

jorndoe

4.2kwe can know that there are no real pink elephants in someone's apartment when they're hallucinating a pink elephant in their apartment, because other people can see that there are no pink elephants, we can tell this via instruments, as well, and we know a lot about how matter behaves and can behave, what's required for there to be an elephant in an apartment, and we also know a lot about how brains work, including how they work on LSD (if that should be the case in this instance), etc — Terrapin Station

jorndoe

4.2kwe can know that there are no real pink elephants in someone's apartment when they're hallucinating a pink elephant in their apartment, because other people can see that there are no pink elephants, we can tell this via instruments, as well, and we know a lot about how matter behaves and can behave, what's required for there to be an elephant in an apartment, and we also know a lot about how brains work, including how they work on LSD (if that should be the case in this instance), etc — Terrapin Station

(y)

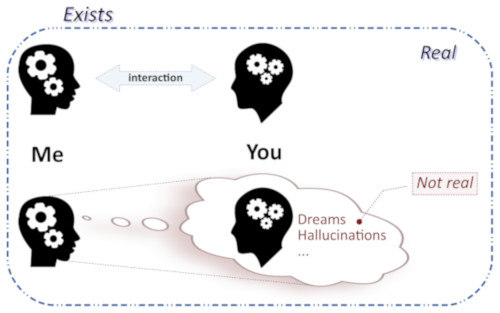

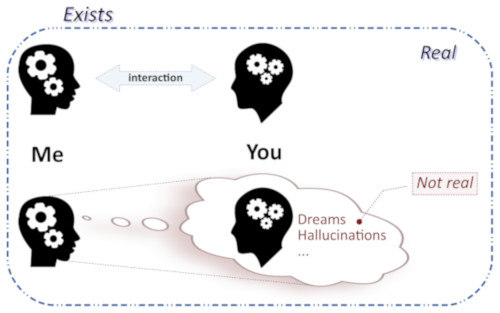

We could differentiate "exist" and "real" (in part) like so:

The bottom "You" would be like those pink elephants.

No elephants were harmed during this event. — Disclaimer -

Dfpolis

1.3kAre hallucinations real? — Galuchat

Dfpolis

1.3kAre hallucinations real? — Galuchat

Yes. They are real experiences potentially informing us of the reality of some neurological disorder. — Dfpolis

I suppose, like synesthesia and phantom limbs perhaps.

That seems to converge on some sort of ordinary realism, surely not mental monism (idealism). — jorndoe

Yes, I am an Aristotelian-Thomistic moderate realist. -

Galuchat

809

Galuchat

809

Yes, but not for that reason.

If reality is to be defined in terms of experience (an awareness event consisting of perception and cognisance), my inquiry ("Are hallucinations real?") indicates a need to differentiate between typical or natural perception, and atypical or unnatural perception (i.e., hallucination, a type of misperception). And different types of perception implies different types of experience, which implies different types of reality.

So, what do we call these different types of reality? -

Dfpolis

1.3kdue to the fact these differences are at least logically irrelevant, insofar as no identifying property of an apple may ever be logically applied to the identity of a horse, we are permitted to disregard the totality of properties or attributes of objects of perception, and merely assign concepts to them a priori as understanding thinks belongs to them necessarily. — Mww

Dfpolis

1.3kdue to the fact these differences are at least logically irrelevant, insofar as no identifying property of an apple may ever be logically applied to the identity of a horse, we are permitted to disregard the totality of properties or attributes of objects of perception, and merely assign concepts to them a priori as understanding thinks belongs to them necessarily. — Mww

No. Type-defining properties (logical essences) are latent in sense data, not arrived at a priori. If they were not latent in experience, our experience of a new instance would not provide us with the data needed to categorize it as a previously known type.

"Accident" has two meanings. One is a property whose presence or absence does not affect our type-classification, e.g. hair color is irrelevant to whether a being is a human. Another is a property which inheres in a substance, not as a raisin in pudding, but as a an aspect that is distinguished from, but still part of the whole. An example would be having flesh. Some accidents in this second sense are essential (e.g. having bones) and others (e.g. skin color) are accidental in the first sense.

I think you mean we each understand what an object is by the way we associate extant experience to it, but those experiences are not seen as part of the core concept of the object. If that is correct, or at least close, then I would agree, because the “core concept” of an object would give to us the thing as it is in itself a posteriori, by presupposing apprehension of the unconditioned (assuming a “core concept” is some sort of ultimate cognitive reduction), which my philosophy will never allow. — Mww

I mean that because of individual experiences we have different associations with things. My mother almost rolled off a cliff at Nevada Falls in Yosemite, so I associate that experience with waterfalls. Others may have entirely positive experiences. None of these associations would lead us to define "waterfall" in a different way.

I am not sure what an "ultimate reduction" would be, but I tend to reject reductionism. -

Mww

5.4kAn ontological hierarchy of sorts? — jorndoe

Mww

5.4kAn ontological hierarchy of sorts? — jorndoe

It is certainly an epistemological hierarchy, and I suppose one could call it an ontological one as well, although purely rational philosophy just grants space and time as ontologically necessary without consideration of their respective origins. That is to say, space and time permit knowledge and without space and time there isn’t any, as far as the human animal is concerned. Besides, physical science covers those ontological fundamentals, even if it is brought up short by its inability to discover the unconditioned just as much as reason is likewise brought up short.

—————-

I'd just say that swimmers in water look different than swimmers out of water. — jorndoe

Quite right, with the monstrous caveat that the appearance of difference doesn’t give you refraction or reflection. One has to extend from mere vision to practical reason in order to qualify why there is a difference at all.

Question: what would a swimmer out of water look like? -

jorndoe

4.2kwhat do we call these different types of reality? — Galuchat

jorndoe

4.2kwhat do we call these different types of reality? — Galuchat

Not sure.

Maybe phenomenological versus empirical in some cases, subjective versus objective in others, fictional versus real in others still?

Existentially mind-dependent: hallucinating, thinking, imagining, memory recall, conceptualizing, fantasies, (day) dreams, phantom pain, headaches, love, denial, ...

And (typically) not: the perceived, the Sun, dinosaur bones, ...

Headaches are real enough. -

Terrapin Station

13.8kI'd just say that swimmers in water look different than swimmers out of water.

Terrapin Station

13.8kI'd just say that swimmers in water look different than swimmers out of water.

(At least we do have some understanding of what's going on with refraction, reflection and such.) — jorndoe

Re optical illusions like that, that's really what something partially submerged in water looks like from a particular reference point. You're getting accurate information from a "system" that consists of everything in the environment between the point of reference and the object(s) in question. -

jorndoe

4.2kmonstrous caveat — Mww

jorndoe

4.2kmonstrous caveat — Mww

Monstrous?

If (what we call) refraction turned out plain wrong (like Aristotle's theory of motion), then we'd perhaps discover something else.

what would a swimmer out of water look like? — Mww

I wasn't part of the photo-shoot, but more in one piece, like the swimmer themselves presumably would report? :) -

jorndoe

4.2kAristotelian-Thomistic moderate realist — Dfpolis

jorndoe

4.2kAristotelian-Thomistic moderate realist — Dfpolis

Substance dualism included?

Substance dualism seems like a sort of "natural intuition" perhaps because of whatever gaps (Levine's explanatory gap, Chalmers' consciousness conundrum, with a nod to Princess Elisabeth of the Palatinate, ...).

It's a non-explanatory assertion, though, doesn't really bridge any gaps, batteries aren't included.

The numinous, wholly other, seems susceptible to the interaction problem, but maybe that's different.

Welcome to The Philosophy Forum!

Get involved in philosophical discussions about knowledge, truth, language, consciousness, science, politics, religion, logic and mathematics, art, history, and lots more. No ads, no clutter, and very little agreement — just fascinating conversations.

Categories

- Guest category

- Phil. Writing Challenge - June 2025

- The Lounge

- General Philosophy

- Metaphysics & Epistemology

- Philosophy of Mind

- Ethics

- Political Philosophy

- Philosophy of Art

- Logic & Philosophy of Mathematics

- Philosophy of Religion

- Philosophy of Science

- Philosophy of Language

- Interesting Stuff

- Politics and Current Affairs

- Humanities and Social Sciences

- Science and Technology

- Non-English Discussion

- German Discussion

- Spanish Discussion

- Learning Centre

- Resources

- Books and Papers

- Reading groups

- Questions

- Guest Speakers

- David Pearce

- Massimo Pigliucci

- Debates

- Debate Proposals

- Debate Discussion

- Feedback

- Article submissions

- About TPF

- Help

More Discussions

- Other sites we like

- Social media

- Terms of Service

- Sign In

- Created with PlushForums

- © 2026 The Philosophy Forum