-

Snakes Alive

743How do you understand the OP?

Snakes Alive

743How do you understand the OP?

I can let Wayfarer speak for himself, but this is what was bolded:

"The physical world cannot be separated from our own efforts to probe it. How could it be otherwise, since we ourselves are embedded in the very world we’re seeking to understand?"

And this was the 'take-home:'

"What I take this to mean, is that objectivity cannot be absolute. And I think the reason this is controversial is that it undermines realism, which is the (usually instinctive) idea that the Universe simply exists as it always does, and that we humans come into it and go out of it in an instant, relative to the vastness of space and time which science observes. But this undermines that view, because it illustrates the sense in which the observer is inextricably part of the picture. We don't, actually, stand outside of, or apart from, the Universe which we are analysing; so what we're analysing cannot be absolutely objective." -

Streetlight

9.1k"The physical world cannot be separated from our own efforts to probe it. — Snakes Alive

Streetlight

9.1k"The physical world cannot be separated from our own efforts to probe it. — Snakes Alive

Yeah, this is rubbish. Or at least, it does not follow. -

Wayfarer

26.2kWhat are your thoughts on Einstein? — andrewk

Wayfarer

26.2kWhat are your thoughts on Einstein? — andrewk

He wasn’t a materialist nor really reductionist. Despite the efforts of people like Dawkins to enlist him for militant atheism, he always denied being atheist, although he certainly disdained organised religion. He had quite an expansive philosophical attitude, sometimes bordering on the mystical, which comes across in many of his popular writings and aphorisms from later in life. But given all that, he was a very determined realist. One of the very good popular books on Einstein and Bohr’s relationship was Manjit Kumar’s ‘Quantum’. It goes into some depth about Bohr and Einsteins’ tussles over this matter which usually consisted of Einstein dreaming up some ‘gedanken’ [thought experiment] and then Bohr labouring to come up with a response. This happened over decades - but Bohr was never bested, according to the book.

The climax of all of that was the EPR paradox, which of course was never able to be made subject to experimental analysis in Einstein’s lifetime, but was to become the subject of the famous Alain Aspect experiments which proved once and for all ‘spooky action at a distance’.

The discomfort that I feel is associated with the fact that the observed perfect quantum correlations seem to demand something like the "genetic" hypothesis. For me, it is so reasonable to assume that the photons in those experiments carry with them programs, which have been correlated in advance, telling them how to behave. This is so rational that I think that when Einstein saw that, and the others refused to see it, he was the rational man. The other people, although history has justified them, were burying their heads in the sand. I feel that Einstein's intellectual superiority over Bohr, in this instance, was enormous; a vast gulf between the man who saw clearly what was needed, and the obscurantist. So for me, it is a pity that Einstein's idea doesn't work. The reasonable thing just doesn't work.

John Stewart Bell, quoted in Quantum Profiles, by Jeremy Bernstein [Princeton University Press, 1991, p. 84]

The point that impresses me about Bohr and Heisenberg, was that their so-called ‘Copenhagen Interpretation’ was not at all a theory or hypothesis, but just musings on what could and couldn’t be said on the basis of what they had discovered. I suppose Einstein’s frequent complaint that quantum physics could not be considered ‘complete’ amount to him saying that it doesn’t provide a conceptually coherent causal chain - a foundational hypothesis. Science had wanted to provide a complete, realist account, and instead stumbled into a mystery which is remains unsolved; the ‘nature of reality’ still remains a Rorschach test. -

Snakes Alive

743Depending on how it's read, it seems to me perfectly unobjectionable given what you've said in this thread. I'm not sure what your issue is.

Snakes Alive

743Depending on how it's read, it seems to me perfectly unobjectionable given what you've said in this thread. I'm not sure what your issue is. -

TheWillowOfDarkness

2.1k

TheWillowOfDarkness

2.1k

It's rubbish because we are defined by our seperation from other things. The issue isn't that our experiences are somehow seperate from the world (and perceptions). Rather, it is no matter this connection of our experiences, things that I encounter are not me.

The mountain I see in the distinct is not me. Another's body I see across the room is not me. Any connection I have with the world around me doesn't undo or remove this seperation.

In any instance were we are investigating the world, this seperation is necessary defined. My experience of investigating the flight of birds is not the flying birds themselves. The birds are other beings who would fly just as well without my investigation. -

Andrew M

1.6kBut this undermines that view, because it illustrates the sense in which the observer is inextricably part of the picture. We don't, actually, stand outside of, or apart from, the Universe which we are analysing; so what we're analysing cannot be absolutely objective.

Andrew M

1.6kBut this undermines that view, because it illustrates the sense in which the observer is inextricably part of the picture. We don't, actually, stand outside of, or apart from, the Universe which we are analysing; so what we're analysing cannot be absolutely objective.

Andrei Linde makes this exact point at 3:16 in this Closer To Truth interview. — Wayfarer

What Linde is saying is that, taken as a whole, the universe is predicted to be static and unchanging (per the Wheeler-DeWitt equation). In order to predict a dynamic and changing universe, as we all observe, you have to split the universe into subsystems, i.e., you, the observer + the rest of the universe.

For some experimental results on this, see Quantum Experiment Shows How Time ‘Emerges’ from Entanglement

That doesn't challenge the idea of objective reality. It just means that what is measured depends on one's frame of reference.

I think the potential philosophical problem is actually at 6:04 in the video where Linde is asked how it is that the universe seems to have been around a lot longer than sentient creatures. He says, "This brings me to the interpretation of quantum mechanics ... Everything becomes real at the moment it is observed ... Before you make an observation there is no such thing as real existence of anything there. But once you make an observation everything looks as if it existed all the time before it happens." -

Andrew M

1.6kThe climax of all of that was the EPR paradox, which of course was never able to be made subject to experimental analysis in Einstein’s lifetime, but was to become the subject of the famous Alain Aspect experiments which proved once and for all ‘spooky action at a distance’. — Wayfarer

Andrew M

1.6kThe climax of all of that was the EPR paradox, which of course was never able to be made subject to experimental analysis in Einstein’s lifetime, but was to become the subject of the famous Alain Aspect experiments which proved once and for all ‘spooky action at a distance’. — Wayfarer

It hasn't been proven - it's an interpretational issue. Per the quantum interpretations table on Wikipedia, roughly half are local interpretations, including QBism. -

Wayfarer

26.2kThanks, fascinating article. I notice this point:

Wayfarer

26.2kThanks, fascinating article. I notice this point:

It suggests that time is an emergent phenomenon that comes about because of the nature of entanglement. And it exists only for observers inside the universe. Any god-like observer outside sees a static, unchanging universe.

Again - the role of the observer is inextricable; you can't assume 'a view from nowhere'. What I think all of this is showing is the role of the observing mind in the establishment of duration. After all, time exists on a scale - if you were a being who lived for a billion years, your sense of duration would be completely different from that of the human. But which is the most accurate? Well, it's a meaningless question; 'accuracy' can only be judged, given a scale.

That doesn't challenge the idea of objective reality. It just means that what is measured depends on one's frame of reference. — Andrew M

What I had said was:

objectivity cannot be absolute. — Wayfarer -

Andrew M

1.6kAgain - the role of the observer is inextricable; you can't assume 'a view from nowhere'. — Wayfarer

Andrew M

1.6kAgain - the role of the observer is inextricable; you can't assume 'a view from nowhere'. — Wayfarer

Agreed.

What I think all of this is showing is the role of the observing mind in the establishment of duration. After all, time exists on a scale - if you were a being who lived for a billion years, your sense of duration would be completely different from that of the human. But which is the most accurate? Well, it's a meaningless question; 'accuracy' can only be judged, given a scale. — Wayfarer

Yes.

objectivity cannot be absolute. — Wayfarer

Do you mean there can be different standards for measurement, depending on the context? -

Wayfarer

26.2kWhat is being measured? There is no absolute material unit or ultimate object. The classical idea of the atom was an indivisible point-particle - a form of the absolute, but conceived in such a way that it can give rise to the myriad things. That, anyway, is the atomism of Lucretius, carried on from Democritus. So I think that is what so disturbed Einstein about the so-called ‘quantum leap’, uncertainty, non-locality and the other aspects of quantum physics - they all tend to undermine the concept of an ultimately existent object. And that has deep philosophical ramifications: it is why the essay in the OP is about ‘the war over reality”. David Lindley’s book Uncertainty is sub-titled ‘the battle for the soul of science’; Major Kumar’s book is sub-titled ‘the great debate about the nature of reality’. It is a front in the so-called ‘culture wars’. Suffice to say I am of one of those with the view that physics itself has definitively undermined scientific materialism. That is the source of the angst that often boils over in these debates. And, it is unresolved.

Wayfarer

26.2kWhat is being measured? There is no absolute material unit or ultimate object. The classical idea of the atom was an indivisible point-particle - a form of the absolute, but conceived in such a way that it can give rise to the myriad things. That, anyway, is the atomism of Lucretius, carried on from Democritus. So I think that is what so disturbed Einstein about the so-called ‘quantum leap’, uncertainty, non-locality and the other aspects of quantum physics - they all tend to undermine the concept of an ultimately existent object. And that has deep philosophical ramifications: it is why the essay in the OP is about ‘the war over reality”. David Lindley’s book Uncertainty is sub-titled ‘the battle for the soul of science’; Major Kumar’s book is sub-titled ‘the great debate about the nature of reality’. It is a front in the so-called ‘culture wars’. Suffice to say I am of one of those with the view that physics itself has definitively undermined scientific materialism. That is the source of the angst that often boils over in these debates. And, it is unresolved.

See The Debate between Plato and Democritus, Werner Heisenberg

Quantum mysticism: gone but not forgotten, Lisa Zyga. -

Janus

18kSo I think that is what so disturbed Einstein about the so-called ‘quantum leap’, uncertainty, non-locality and the other aspects of quantum physics - they all tend to undermine the concept of an ultimately existent object. And that has deep philosophical ramifications: it is why the essay in the OP is about ‘the war over reality”. — Wayfarer

Janus

18kSo I think that is what so disturbed Einstein about the so-called ‘quantum leap’, uncertainty, non-locality and the other aspects of quantum physics - they all tend to undermine the concept of an ultimately existent object. And that has deep philosophical ramifications: it is why the essay in the OP is about ‘the war over reality”. — Wayfarer

But does QM undermine the very notion of their being anything ultimate or fundamental? I mean, why not 'field' or 'process'? -

Janus

18k

Janus

18k

There is a Quantum Field Theory, isn't there? Are you saying that it is vague?

In any case, if you are drawing a distinction with objects here, what makes you think that objects in general are not vague? For example you see a tree and I see the same tree, it happens all the time: but what precisely is that entity which we both see?

Anyway you didn't answer the first question. -

Wayfarer

26.2kMy understanding is that it was the discovery of the non-existence of anything that could be understood as a real, fundamental particle that precipitated the crisis of interpretation. You know - if atoms aren't real, then what is everything made from?!? That’s the impression I got from reading David Lindley’s book Uncertainty, and Manjit Kumar’s book Quantum, both of which were about the Einstein-Bohr-Heisenberg debates (Kumar's was better IMO). That’s why I keep referring to the well-known exclamation of Einstein’s - ‘Doesn’t the moon continue to exist when you’re not looking at it?’ This was an expression of exasperation - it was meant to prompt the answer, ‘well of course it does!’ Einstein thought the whole business an offence to common sense, basically ridiculous. That’s why he kept insisting that quantum mechanics couldn’t be a complete theory. He spent many of his Princeton years trying to find some way of proving this - to no avail, as I understand it.

Wayfarer

26.2kMy understanding is that it was the discovery of the non-existence of anything that could be understood as a real, fundamental particle that precipitated the crisis of interpretation. You know - if atoms aren't real, then what is everything made from?!? That’s the impression I got from reading David Lindley’s book Uncertainty, and Manjit Kumar’s book Quantum, both of which were about the Einstein-Bohr-Heisenberg debates (Kumar's was better IMO). That’s why I keep referring to the well-known exclamation of Einstein’s - ‘Doesn’t the moon continue to exist when you’re not looking at it?’ This was an expression of exasperation - it was meant to prompt the answer, ‘well of course it does!’ Einstein thought the whole business an offence to common sense, basically ridiculous. That’s why he kept insisting that quantum mechanics couldn’t be a complete theory. He spent many of his Princeton years trying to find some way of proving this - to no avail, as I understand it.

A similar kind of exasperation lay behind Schrodinger’s cat - he was pointing out how ridiculous the implications of his equation were with a real-life analogy. He wasn’t just being mischievous:

Letter to Einstein (13 June 1946), as quoted by Walter Moore in Schrödinger: Life and Thought (1989)God knows I am no friend of probability theory, I have hated it from the first moment when our dear friend Max Born gave it birth. For it could be seen how easy and simple it made everything, in principle, everything ironed and the true problems concealed. Everybody must jump on the bandwagon. And actually not a year passed before it became an official credo, and it still is. — Erwin Schrodinger

For everyone involved there was real angst; Heisenberg recalled being reduced to tears around Bohr’s kitchen table on some occasions, so bitter were the arguments (he was very much the junior partner.)

And I don’t think it’s ever really been resolved. I think basically the discoveries enabled such an bonanza that after the war questions of interpretation became passé. There was gold in them thar hills, even if nobody knew how it got there. Shut up and calculate. That’s why, when Everett came along, the field was ripe for the picking:

Everett’s scientific journey began one night in 1954, he recounted two decades later, “after a slosh or two of sherry.” He and his Princeton classmate Charles Misner and a visitor named Aage Petersen (then an assistant to Niels Bohr) were thinking up “ridiculous things about the implications of quantum mechanics.” During this session Everett had the basic idea behind the many-worlds theory, and in the weeks that followed he began developing it into a dissertation.

From a Scientific American profile (and worth a read; tragic character that he was.)

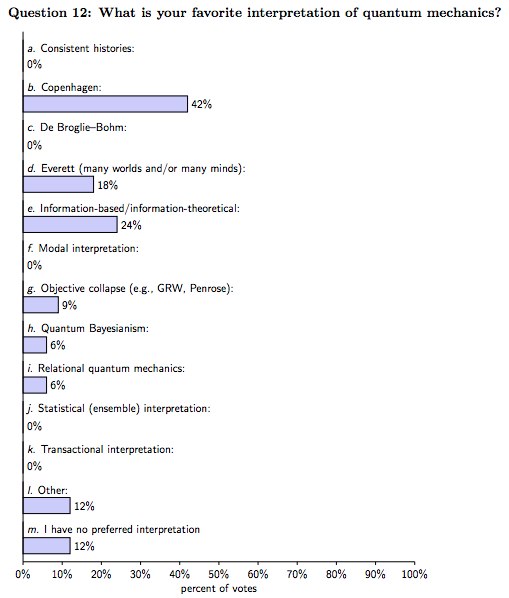

Everett's interpretation now has many followers. And this is still where it’s at, although a straw poll of physicists published on Sean Carroll's blog looked like this:

-

Andrew M

1.6kSo I think that is what so disturbed Einstein about the so-called ‘quantum leap’, uncertainty, non-locality and the other aspects of quantum physics - they all tend to undermine the concept of an ultimately existent object. And that has deep philosophical ramifications: it is why the essay in the OP is about ‘the war over reality”. — Wayfarer

Andrew M

1.6kSo I think that is what so disturbed Einstein about the so-called ‘quantum leap’, uncertainty, non-locality and the other aspects of quantum physics - they all tend to undermine the concept of an ultimately existent object. And that has deep philosophical ramifications: it is why the essay in the OP is about ‘the war over reality”. — Wayfarer

More recent philosophical discussion has moved on from the reality versus mysticism debates between the founders of quantum mechanics. "The war over reality" essay is about whether the quantum state describes the underlying world (intrinsic realism) or information about observers (participatory realism). Fuch's QBism and Rovelli's RQM are examples of the latter (characterized as Type-II in the paper linked below).

Type-II interpretations do not deny the existence of an objective world but, according to them, quantum theory does not deal directly with intrinsic properties of the observed system, but with the experiences an observer or agent has of the observed system. — Interpretations of quantum theory: A map of madness

What I want to emphasize at the moment is that I cannot see any way in which the program of QBism has ever contradicted what Einstein calls the program of “the real.” — On Participatory Realism - Chris Fuchs -

Wayfarer

26.2kI’ll settle for ‘participatory realism’ but I would be surprised if Einstein, had he been around, would have agreed with it.

Wayfarer

26.2kI’ll settle for ‘participatory realism’ but I would be surprised if Einstein, had he been around, would have agreed with it.

//ps// from the Fuchs article:

These views have lately been termed “participatory realism” to emphasize that rather than relinquishing the idea of reality (as they are often accused of), they are saying that reality is more than any third-person perspective can capture.

:up:

//ps//Because ‘participatory realism’ means, not that the conversation has ‘moved on’ from reality v mysticism, but that the mystics won. -

Andrew M

1.6k//ps// from the Fuchs article:

Andrew M

1.6k//ps// from the Fuchs article:

These views have lately been termed “participatory realism” to emphasize that rather than relinquishing the idea of reality (as they are often accused of), they are saying that reality is more than any third-person perspective can capture. — Wayfarer

So the argument is that is necessary to index the quantum state to a participant (broadly conceived). As an analogy, there is nothing mystical about ordinary statements like, "The apple is red" or "I am in pain". But they are statements that are only meaningful when indexed to individual sentient creatures with particular sensory capabilities. There is no intrinsic "redness" or "pain" in the world.

The way QBism conceives of indexing compared to RQM is different (Bayesian probabilities versus relative reference frames). But the general idea is that there needs to be a natural integration of first and third person perspectives - a view from somewhere - to make proper sense of quantum mechanics.

Which, as it happens, is something that the natural and holistic approaches of Aristotelian hylomorphism and Peircean pragmatism, to name but two, both do.

Welcome to The Philosophy Forum!

Get involved in philosophical discussions about knowledge, truth, language, consciousness, science, politics, religion, logic and mathematics, art, history, and lots more. No ads, no clutter, and very little agreement — just fascinating conversations.

Categories

- Guest category

- Phil. Writing Challenge - June 2025

- The Lounge

- General Philosophy

- Metaphysics & Epistemology

- Philosophy of Mind

- Ethics

- Political Philosophy

- Philosophy of Art

- Logic & Philosophy of Mathematics

- Philosophy of Religion

- Philosophy of Science

- Philosophy of Language

- Interesting Stuff

- Politics and Current Affairs

- Humanities and Social Sciences

- Science and Technology

- Non-English Discussion

- German Discussion

- Spanish Discussion

- Learning Centre

- Resources

- Books and Papers

- Reading groups

- Questions

- Guest Speakers

- David Pearce

- Massimo Pigliucci

- Debates

- Debate Proposals

- Debate Discussion

- Feedback

- Article submissions

- About TPF

- Help

More Discussions

- Block universe+eternal universe= infinite universe?

- Some interesting thoughts about Universes. The Real Universe and The Second Universe.

- Existence of an external universe to the physical universe

- Possible revival of logical positivism via simulated universe theory.

- What is the role of cognition and planning in a law governed universe?

- Other sites we like

- Social media

- Terms of Service

- Sign In

- Created with PlushForums

- © 2026 The Philosophy Forum