-

Fire Ologist

1.7k

Fire Ologist

1.7k

The point is, the whole of the empirical world in space and time is the creation of our understanding, — Bryan Magee Schopenhauer's Philosophy, Pp 106-107

I agree with this. We can replace “in space and time” with the “as we understand it” from your description above.

Because the OP asked about “physical world”, I am trying focus more on the thing-in-itself part of the equation, which as empirical, is the world mediated by senses.

To paraphrase, the below three say basically the same thing:

1. The point is, the whole of the empirical world in space and time is the creation of our understanding,

2. The point is, the whole of the empirical world as we understand it is the creation of our understanding,

3. The point is, the whole of the empirical world that we take as representation is the creation of our understanding,

The first puts the separate thing in it self in context of extension and temporality which are features of the understanding. The second focuses on the operation of the understanding upon the thing in itself (really saying the same thing more generally and not just in context of space and time). The third focuses on the operation of the thing in itself upon the senses that build the representation.

But they build the representation out of two sources - the understanding AND the thing in itself.

There is a tendency to ignore the thing in itself in the equation. Just because our understanding can only be comprised of phenomena, this doesn’t mean phenomena are only comprised of our understanding. There still is (or can be I should say) an empirical world absent perspective and sensation. Such a world-in-itself is wholly inaccessible, like each thing we would intuit about the objects created by sensation, but nevertheless must exist to build up all of this apparatus called subjective experience. -

Fire Ologist

1.7kAn objective world, by definition, would not require a subject or its ideals at all. — noAxioms

Fire Ologist

1.7kAn objective world, by definition, would not require a subject or its ideals at all. — noAxioms

Are you utterly isolated, perhaps the sole being there is, fabricating each of the impressions or ideals in your experience?

Or are you utterly isolated, fabricating each of the impressions or ideals in your experience using incomplete and vague data from outside of you like a sort of mental clay? So you are not the only thing in the universe, you just cannot communicate with any of the other things, and instead translate and transform those things into nice packages for your own isolated world?

Or are you one of many physical things that occasionally has to avoid being hit when crossing the street to pick out a unique and distinct sandwich to be placed in a distinct belly to relieve a distinct and localized feeling of hunger, and you just can’t explain all of that clearly because of the second option?

The only way to save any knowledge of the thing in itself is to understand that we couldn’t have this conversation without something separate from both of us to mediate it. We aren’t using telepathy. We are using material objects between us. They exist with no need to declare their distinctions. Through things physical objects, we can demonstrate mental ideals that only other minds can take up. We make our own idealistic declarations out of those separate objects like when Intake the alphabet of shapely things in themselves and make the phenomena known as “alphabet”. But we who can translate sounds and colors into “objects” know something in itself is also declared when some other mind returns with a rebuttal that is not gibberish. -

JuanZu

382My attempts to find a non-fictional example of an object not being an ideal has failed. This is strong evidence for the conclusion reached. — noAxioms

JuanZu

382My attempts to find a non-fictional example of an object not being an ideal has failed. This is strong evidence for the conclusion reached. — noAxioms

Think about the embodied-mind. There would be a relation between our ability to grasp objects and the appearance of things as objects in our perception.

I think what you expect to find is an object unmediated by our categories, for example. But that is like saying we are going to perceive something without perceiving. Every perception involves an adaptation, an interpretation. There is no access to reality that is not mediated, but we can ask why our means are embedded in reality, and above all, we can ask why they work and what the link is between the world we are in and our categories, our language, our ideas, etc. Therefore, the world would have something ideal-ish that allows our thinking and our perception to maintain a certain continuity with the world. -

Count Timothy von Icarus

4.3k

Count Timothy von Icarus

4.3k

In a search for an objective object, yes, I want that. Seems completely impossible, so the conclusion is that all these things are but ideals.

I would agree to that, with the large caveat that "ideals," (inclusive of the accidental properties of particulars) are generated by the physical properties of objects, which include (perhaps irreducible) relations to minds. So, I think that is the right conclusion, just not in the sense that objects exist "only in the mind." Objects exist in as a function of the relationships between minds and the things that lie outside them.

Baring some sort of solipsism, ontological differences have to underpin phenomenal differences. This would be true even for Berkeley. And "physical" seems to be a good concept for denoting how these differences exist. -

Fire Ologist

1.7k

Fire Ologist

1.7k

I think what you expect to find is an object unmediated by our categories, for example. But that is like saying we are going to perceive something without perceiving. Every perception involves an adaptation, an interpretation. There is no access to reality that is not mediated, but we can ask why our means are embedded in reality, and above all, we can ask why they work and what the link is between the world we are in and our categories, our language, our ideas, etc. Therefore, the world would have something ideal-ish that allows our thinking and our perception to maintain a certain continuity with the world. — JuanZu

This is exactly what I’m trying to say.

There is a reason we can speak meaningfully to each other, that we can carry ideals to other minds; there is some basis in a world separate from both of us, something ideal-ish or objective.

Just because we can’t be realists, doesn’t mean realism is not there. It’s cloaked. -

noAxioms

1.7k

noAxioms

1.7k

None of the above. Third option looks like an argument either for or against free will. I do admit the use of ideals in my interactions with the world 'out there'.Are you utterly isolated, perhaps the sole being there is, fabricating each of the impressions or ideals in your experience?

Or are you utterly isolated, fabricating each of the impressions or ideals in your experience using incomplete and vague data from outside of you like a sort of mental clay? So you are not the only thing in the universe, you just cannot communicate with any of the other things, and instead translate and transform those things into nice packages for your own isolated world?

Or are you one of many physical things that occasionally has to avoid being hit when crossing the street to pick out a unique and distinct sandwich to be placed in a distinct belly to relieve a distinct and localized feeling of hunger, and you just can’t explain all of that clearly because of the second option? — Fire Ologist

Agree with this. The separate mediation is apparently not a 'thing'. It is just physics, motion of material and such, having no meaning until reinterpreted back into ideals by something that isn't me.to understand that we couldn’t have this conversation without something separate from both of us to mediate it.

Material yes. Objects, not so much. Their being objects is only an ideal, per pretty much unanimous consensus of the posters in this topic. Physics works and does its thing all without human designations of where the boundaries of 'separate systems' are. The need to declare their distinctions is only a need of the communicating intellects.We are using material objects between us.

Thank you for your continued input. It seems we're mostly hacking out the same ideas with different language surrounding it. I'm not in the habit of articulating this sort of interaction since it's sort of a different way of looking at things for me.

Agree with all this. Some comments. We have little access to reality that is not mediated. Reality itself has such unmediated access, but that doesn't qualify as perception.I think what you expect to find is an object unmediated by our categories, for example. But that is like saying we are going to perceive something without perceiving. Every perception involves an adaptation, an interpretation. There is no access to reality that is not mediated, but we can ask why our means are embedded in reality, and above all, we can ask why they work and what the link is between the world we are in and our categories, our language, our ideas, etc. Therefore, the world would have something ideal-ish that allows our thinking and our perception to maintain a certain continuity with the world. — JuanZu

Some examples would help here. Are you only talking about relations to minds?I would agree to that, with the large caveat that "ideals," (inclusive of the accidental properties of particulars) are generated by the physical properties of objects, which include (perhaps irreducible) relations to minds. — Count Timothy von Icarus

Not otherwise sure of what you're saying. In particular, what sort of properties (other than a relation to a mind) would an object have that a mere subset of material doesn't? What would distinguish the two cases? There is 'kind' for instance. Here is a relatively contiguous region of state X or material M, such as what a human would designate as a cloud. The atmospheric conditions external to the cloud are different than the conditions within it, and that simple change of kind from one region to the next defines a fairly natural boundary for a physical object. It isn't 'connected' (one of the attempted but failed definitions), but at least it is (more or less) contiguous. The more-or-less part comes into play when it gets less defined if there is one cloud or two smaller ones that are merely nearby. Physics obviously cares not about this distinction. -

Fire Ologist

1.7kAgree with this. The separate mediation is apparently not a 'thing'. It is just physics, motion of material and such, having no meaning until reinterpreted back into ideals by something that isn't me. — noAxioms

Fire Ologist

1.7kAgree with this. The separate mediation is apparently not a 'thing'. It is just physics, motion of material and such, having no meaning until reinterpreted back into ideals by something that isn't me. — noAxioms

So if you would admit there are two distinct people in the universe, but don’t see any distinct physical objects apart from your own idealizations, is the distinction you make between you and me only ideal, or do I have to have some sort of physics to me that you can let speak for itself? -

Wayfarer

26.2kI don't much know the teachings of the famous guys — noAxioms

Wayfarer

26.2kI don't much know the teachings of the famous guys — noAxioms

Bernardo Kastrup is worth becoming acquainted with if you want to know something about current philosophical idealism. Interview here. (His organisation has just published the second book by Federico Faggin, who developed the first microprocessor before having a major epiphany and turning his attention to "consciousness studies". I read his "Silicon" last year.)

That was in reaction to your Magee quote, and it seems to presume a more fundamental (proper) idealism than the one described by your paper or Pinter. — noAxioms

Oh, I don't know. True, Pinter's books doesn't mention 'idealism' but there are 27 references to Kant. And there's a strong (if contested) relationship between Kant and modern cognitive science. It's actually very hard to get clear on what idealism actually means, but it certainly doesn't mean what a lot of people take it for, 'spooky ethereal mind-stuff'.

That we put words to sets of material that we find useful does not imply that the material behind it is challenged. — noAxioms

That there is 'material behind it' is precisely the belief in question! -

ucarr

1.9k

ucarr

1.9k

When we look at the premise: What constitutes an 'object' is entirely a matter of language/convention. There's no physical basis for it., we see that the interface connecting language with physical parts of the natural world is denied. — ucarr

Is ‘object’ the antecedent of ‘it.’?

Well for one, the suggestion is that convention is very much the interface between the physical world and 'object'. Convention comes from language and/or utility. So the interface is not denied, but instead enabled by these things. — noAxioms

Does “convention” equal “A way in which something is usually done in accordance with an established pattern.”?

Are “convention” and “utility” the antecedents for “things.”?

Are you saying ‘object’ is a non-physical construction of the mind?

Are you saying the mind constructs an interpretation of the physical world, and that that construction is radically different in form from its source?

Does the mind_physical world interface come before the interpretation?

If the mind_physical world interface is contemporary with the interpretation, must we conclude the mind never perceives the physical world directly? -

javi2541997

7.2kI know those questions are for @noAxioms, but they are so interesting that I want to dive into them as well.

javi2541997

7.2kI know those questions are for @noAxioms, but they are so interesting that I want to dive into them as well.

Does “convention” equal “A way in which something is usually done in accordance with an established pattern.”? — ucarr

I think it does. But the point here is to know to what extent things exist or not due to universal convention. I would like to use the example of a few pages before: a twig is followed by a tree and then the combination of these two makes the forest. This set is interesting. I personally believe a set of different things are dependent on universal convention, for instance. Furthermore, if we are focused on non-material “things” like time, justice, property or democracy.

Are “convention” and “utility” the antecedents for “things.”? — ucarr

ucarr, what do you mean by “antecedents” here? I think convention and utility are attachments to physical objects.

Are you saying ‘object’ is a non-physical construction of the mind? — ucarr

This is a great question. I would like to know the answer of @noAxioms. When I exchanged some thoughts with him, he claimed everything object is connected to something. I guess he was referring to the construction of the mind.

Is ‘object’ the antecedent of ‘it.’? — ucarr

Ahh, which came first? The classic golden question. I think an object is a representation of reality which holds both primary and secondary qualities. I mean, we call the “object” the thing that can be measured, seen, colored, compared, etc. and other types of properties which make the object an “it”. So, even if I might be wrong, I would say “object” came first than “it.” -

noAxioms

1.7kApologies to all for slow reply. It's gets busy on some days.

noAxioms

1.7kApologies to all for slow reply. It's gets busy on some days.

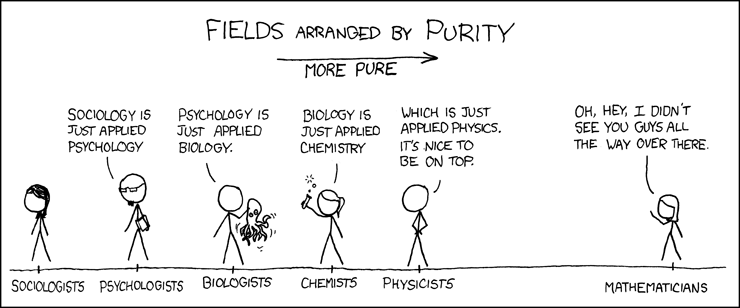

I'll try to clarify. There are multiple fields, and a given description must be consistent with one of the fields. This xkcd comic illustrates what I mean:So if you would admit there are two distinct people in the universe, but don’t see any distinct physical objects apart from your own idealizations, is the distinction you make between you and me only ideal, or do I have to have some sort of physics to me that you can let speak for itself? — Fire Ologist

The fields as I see relevant here are ideals, mind, biology, chemistry, physics, mathematics. One can use any of them, but the two in bold are frequently referenced. In the mental field, there are ideals, which are say people, forum posts, letters, sounds, etc. In the physics field, there are none of these things. Objects are at best particles interacting with each other according to physical law.

So yes, I am a being with a mind, and that lets me identify/name my ideals: of multiple people existing for instance, including myself (just another ideal). The mind is not fundamental at all since each field supervenes on the field to the right of it. Hard idealism stops the list there, making mind fundamental. I don't know which philosophers suggests that sort of hard idealism. I don't much care.

Confusion results if fields are mixed. For instance, there are those that assert that computers can't be conscious because their operation is nothing but transistors switching on and off, which is like saying that humans can't be conscious because they're nothing but neurons switching on and off. The comments are not even wrong because they mix fields (mind vs electronics say).

Of course, the people that assert the lack of machine consciousness are often ones that also assert that human consciousness is not a function of neuron operation, so there's that.

What, like the 4040 or something even older? Interesting read I bet.one Federico Faggin, who developed the first microprocessor — Wayfarer

Well, what you quote from Pinter seems to make sense, and if he never mentions idealism, then there's your significant difference between idealism and what is becoming fairly clear to me.True, Pinter's books doesn't mention 'idealism'

I never considered idealism to be spooky etherial mind stuff. It is actually fairly consistent, a version of realism (with the problems that come with that), and it simply uses an epistemological definition of what is real. There is nothing wrong or spooky with such a definition. I just don't choose to use it.

I know. I didn't say otherwise.That there is 'material behind it' is precisely the belief in question!

Pretty much that, yes. If humans find sufficient utility in a given convention, a word might be assigned to it. So you have one word 'grape' that identifies an edible unit of food from this one species of vine, and 'cluster' as a different unit describing what is picked from the vine, as opposed to what is left behind. We find utility in both those units, so two words are coined to make this convention part of our language.Does “convention” equal “A way in which something is usually done in accordance with an established pattern.”? — ucarr

An ideal, which yes, is a construct of the mind. As for it being non-physical, not so keen on that since mind seems to be as physical as anything else. Opinions on this vary of course.Are you saying ‘object’ is a non-physical construction of the mind?

I'll agree with that even if I didn't particularly say as much anywhere in this topic.Are you saying the mind constructs an interpretation of the physical world, and that that construction is radically different in form from its source?

Don't know what you mean by ';comes before'. That the interface happens at an earlier time than the interpretation that forms from it? Much of interpretation is instinctive, meaning it evolved long before the birth of an individual and the interface to that individual.Does the mind_physical world interface come before the interpretation?

People have different definitions of what it means to directly perceive something, what the boundaries are for instance. There's no one convention that everybody uses.must we conclude the mind never perceives the physical world directly?

This sounds like 'objective convention', and the lack of example seems to suggest the conventions are either human or that of some other cognitive entity. Many different things will find utility in the same conventions, so there is some aspect of universality to it.But the point here is to know to what extent things exist or not due to universal convention. — javi2541997

That example was meant to demonstrate the opposite. If I reach out and touch the bark and ask how large 'this' is, am I talking about the twig, branch, tree, forest, or something else? If there was a physical convention, there'd be an answer to that. There seemingly isn't.I would like to use the example of a few pages before: a twig is followed by a tree and then the combination of these two makes the forest. This set is interesting. I personally believe a set of different things are dependent on universal convention, for instance.

That was given a definition of 'connected' as 'the existence of forces between the two halves in question'. I didn't like that definition precisely because it rendered everything connected. There cannot be two things.When I exchanged some thoughts with him, he claimed everything object is connected to something. -

Fire Ologist

1.7kObjects are at best particles interacting with each other according to physical law. — noAxioms

Fire Ologist

1.7kObjects are at best particles interacting with each other according to physical law. — noAxioms

Physical, not mental, basis?

And I guess the distinctions between psychology and biology and physics are ideal only?

My point is, you cannot speak, we cannot form an ideal, without some real distinctions apart from the mind on which we make any move, perform any act, posit any field, say anything like “particle”.

We may always be wrong about the separate mind-independent object, except that it is there, otherwise we cannot speak. Speaking places the ideal back into a separate world of objects (letters, words, sentences, paragraphs), where, like the other objects, they can either float freely among, or butt up against, or connect with, the world. These words only express their meaning in other minds. But they are still particles, or in a distinct field that is there regardless of my idealistic abilities. -

Fire Ologist

1.7kIf I reach out and touch the bark and ask how large 'this' is, am I talking about the twig, branch, tree, forest, or something else? — noAxioms

Fire Ologist

1.7kIf I reach out and touch the bark and ask how large 'this' is, am I talking about the twig, branch, tree, forest, or something else? — noAxioms

Why did we ever conceive of the notion of “object” in the first place? Why did we not always know “when I reach out and touch, I am touching one giant dinstiction-free object?”

Why would a “twig” or a “tree” confuse us when we touch “this”?

Are we constructing the problem AND constructing the objects that purport to solve the problem? -

javi2541997

7.2kThat example was meant to demonstrate the opposite. If I reach out and touch the bark and ask how large 'this' is, am I talking about the twig, branch, tree, forest, or something else — noAxioms

javi2541997

7.2kThat example was meant to demonstrate the opposite. If I reach out and touch the bark and ask how large 'this' is, am I talking about the twig, branch, tree, forest, or something else — noAxioms

I think I understand you better, mate. But it surprised me when I read that, according to your view, the Midas example proves the opposite of what I say. Well, yes, if we talk about measurement, and you ask me how large the bark is, we are in different physical objects independent of each other then.

Nonetheless, I think we should not dismiss the fact of the “set” of the physical object “tree” and the physical group “forest”. I still claim they are all a dependent set. If there is no twig, there is no bark either to measure.

Imagine a building for a second. This structure encloses walls, roof, floors, columns, etc. If I talk about a “building” I also refer to all those elements, right?

Well, the same happens to a tree and therefore the forest. Whatever part I am referring to, it includes the sum of the set.

If there was a physical convention, there'd be an answer to that. There seemingly isn't. — noAxioms

Why does it appear like there are no answers? -

ucarr

1.9k

ucarr

1.9k

Are you saying ‘object’ is a non-physical construction of the mind? — ucarr

An ideal, which yes, is a construct of the mind. As for it being non-physical, not so keen on that since mind seems to be as physical as anything else. Opinions on this vary of course. — noAxioms

Consider: a human individual navigates his way through the natural world. His perceiving mind processes the incoming data from his senses towards the construction of an interpretation. His interpretation is his mental picture. It resides within his cranium. As such, it is an internalized representation of something at least partially outside of and beyond the dimensions of his cranium.

Do the material details of the natural world constrain to some measurable degree the material details of the human's constructed interpretation? For example, there's a tree that the man sees outside of his house. If we can understand that the tree, as an independent material detail of an independent reality beyond the dimensions of the man's cranium, has a height of ten feet, whereas the man's house has a height of fifteen feet, can we conclude that the constructed interpretation within the man's cranium will likewise depict a tree with a height shorter than the height of the house?

If we arrive at this conclusion, do we know that the constructed interpretation has an analogical relationship with the independent and external world?

Can we answer "yes," the independent and external world does indeed constrain to some measurable degree the material details of the human's constructed interpretation? -

ucarr

1.9k

ucarr

1.9k

Are “convention” and “utility” the antecedents for “things.”? — ucarr

ucarr, what do you mean by “antecedents” here? I think convention and utility are attachments to physical objects. — javi2541997

Okay. Let's look at my dialog with noAxiom once again:

When we look at the premise: What constitutes an 'object' is entirely a matter of language/convention. There's no physical basis for it., we see that the interface connecting language with physical parts of the natural world is denied. — ucarr

...we see that the interface connecting cognitive language with physical parts of the natural world is denied. — ucarr

This denial raises the question: How does language internally bridge the gap separating it from the referents of the natural world that give it meaning? — ucarr

I don't see a denial of the indicated connection, so it's a question you must answer. — noAxioms

How is my understanding of your quote a mis-reading of it? — ucarr

Well for one, the suggestion is that convention is very much the interface between the physical world and 'object'. Convention comes from language and/or utility. So the interface is not denied, but instead enabled by these things. — noAxioms

Are “convention” and “utility” the antecedents for “things.”? — ucarr

If find it useful to begin an exam of the writer's post by asking grammatical questions. That's all I'm investigating here. I'm not yet examining philosophical content.

If the answer is "yes," "convention," and "utility" are the antecedents for "things," then noAxioms is telling me the interface between physical world and object consists of established language patterns interwoven with sensory (visual, tactile etc.) data. Words are signs with material details of the natural world as referents.

Some important details about how the interweave of physical world and object is configured is what I'm now examining. -

noAxioms

1.7k

noAxioms

1.7k

There is no mental anything at the physics level. I'm talking about territory here, not map. Map is our only interface from mental ideals to territory. A real particle in itself probably bears little resemblance to our typical mental model of it.Physical, not mental, basis? — Fire Ologist

Those words all refer to ideals, so yes, distinctions between them seem ideal.And I guess the distinctions between psychology and biology and physics are ideal only?

Unclear on what you mean here. Examples perhaps? I think we're talking past each other since there's talk of both ideals (references) and the referents, of both map and territory.My point is, you cannot speak, we cannot form an ideal, without some real distinctions apart from the mind on which we make any move, perform any act, posit any field, say anything like “particle”.

It has utility, a general word to encompass a given subset of material without further classification into a more specific object kind.Why did we ever conceive of the notion of “object” in the first place? — Fire Ologist

We don't know what is being referenced, but even in the act of reaching out and touching in a specific way, a convention is conveyed, and I would probably guess correctly on first try what was meant. Clue: Probably not the forest.Why did we not always know “when I reach out and touch, I am touching one giant dinstiction-free object?”

Remind me what the Midas example 'proves'...But it surprised me when I read that, according to your view, the Midas example proves the opposite of what I say. — javi2541997

That's a lot different than asking what 'this' is, and touching the twig bark. But even if the 'object' is partially demarked by the word 'bark', it still leaves the extent of it unspecified. Bark of just the twig? The whole tree? Something else?and you ask me how large the bark is

Probably, yes. The word invokes a convention, and the convention typically includes all those parts, but how about the piles or the utility hookups? Where does the building stop? Does it include the furniture and people? That question was asked in the OP where I explore the concept of what you weigh, and exactly when that weight changes.Imagine a building for a second. This structure encloses walls, roof, floors, columns, etc. If I talk about a “building” I also refer to all those elements, right?

But in the absence of language, how does anything 'know' that 'building' is the object of interest?

Category error. There are answers, but not in the wrong category.Why does it appear like there are no answers?

Fine. That's a fairly concise summary of a physicalist view.His interpretation is his mental picture. It resides within his cranium. As such, it is an internalized representation of something at least partially outside of and beyond the dimensions of his cranium. — ucarr

Yes. The mental model is built from perceived experiences. First tree, then he perceives the tree, and puts the short tree into his mental model of the local reality.Do the material details of the natural world constrain to some measurable degree the material details of the human's constructed interpretation?

We assume that. Saying 'know' presumes some details that cannot be known, per say Cartesian skepticism. I'm indeed assuming that my perception of the tree outside is not a lie.If we arrive at this conclusion, do we know that the constructed interpretation has an analogical relationship with the independent and external world?

Maybe I'm misreading your quotes. I don't know. Given a convention, an object can often be demarked. Language is one way to convey the desired convention.How is my understanding of your quote a mis-reading of it? — ucarr

Convention in this context is the binding of an agreed upon demarking of a specific thing with a language construct, a word say, but not always a word. Utility is used like 'usefulness'. There is utility in assigning the word 'mug' to the collection of ceramic that holds my coffee. A mug is a fairly unambiguous 'object' to a typical human, although one can still indicate its parts in some contexts.If find it useful to begin an exam of the writer's post by asking grammatical questions. That's all I'm investigating here. I'm not yet examining philosophical content. -

Fire Ologist

1.7kThere is no mental anything at the physics level. I'm talking about territory here, not map. Map is our only interface from mental ideals to territory. — noAxioms

Fire Ologist

1.7kThere is no mental anything at the physics level. I'm talking about territory here, not map. Map is our only interface from mental ideals to territory. — noAxioms

If you say there is any level where there is “no mental anything” aren’t you pointing out a non-ideal thing, an object in itself regardless of the mental? Haven’t you admitted there is a physical (non-mental) world where objects (particles) speak for themselves? -

javi2541997

7.2kThe word invokes a convention, and the convention typically includes all those parts, but how about the piles or the utility hookups? Where does the building stop? Does it include the furniture and people? That question was asked in the OP where I explore the concept of what you weigh, and exactly when that weight changes. — noAxioms

javi2541997

7.2kThe word invokes a convention, and the convention typically includes all those parts, but how about the piles or the utility hookups? Where does the building stop? Does it include the furniture and people? That question was asked in the OP where I explore the concept of what you weigh, and exactly when that weight changes. — noAxioms

Yes, I follow you and the sense of your OP. I remember when we talked about chopping the twig off, for instance. I know that it would sound silly to say that without a twig, the tree no longer exists, and therefore, the forest either. But this is exactly the trace I want to keep up! I think the example of the house is better.

You asked me: Where does the building stop? Does it include the furniture and people?

Of course, it includes furniture and people. :smile:

What would be the point of constructing a building, then? The building, as an object, precisely stops when it lacks everything above. The combination of the walls, furniture, ceiling, roof, and people makes the 'building', and when an element of the set is left, the building as an object is senseless. I wish I could go deeper regarding the example of the twig and the forest because I still see symmetry in both cases.

But in the absence of language, how does anything 'know' that 'building' is the object of interest? — noAxioms

The object of interest is inherent in the building. The remaining 'things' are attached to it. They ‘know’ that the building is of interest to them. -

noAxioms

1.7kx

noAxioms

1.7kx

Yes to all, except maybe the 'speak' part. Not sure how you meant that choice of word.If you say there is any level where there is “no mental anything” aren’t you pointing out a non-ideal thing, an object in itself regardless of the mental? Haven’t you admitted there is a physical (non-mental) world where objects (particles) speak for themselves? — Fire Ologist

'Level' is a better word than the 'field' that xkcd used, which was meant more as a field of study.

If I point to a severed twig, I'm probably not indicating the tree, although severed twigs and such are very much still part of a forest, so barring a convention, what is being indicated is still questionable.Yes, I follow you and the sense of your OP. I remember when we talked about chopping the twig off, for instance. I know that it would sound silly to say that without a twig, the tree no longer exists — javi2541997

No, I asked where 'this' stops. I never said 'building'. Using a word like that invokes the convention, however inexact.You asked me: Where does the building stop?

I'm part of a building if in one. Not sure if that's standard convention. Most would say the humans occupy it, but are not themselves part of the building. But my early example of a human typically includes anything that occupies or is even carried by the human. They're all part of the human. Not so much with the building. Different convention.Of course, it includes furniture and people. :smile:

Is it relevant? It could be. An object is demarked by its purpose, but that doesn't help. I point to 'this', and am I talking about the brick (purpose to support and seal a wall), the wall (similar purposes), the suite, or the building (different purposes), or something else (to generate rent income)What would be the point of constructing a building, then?

Still, purpose is defined by the humans that find utility in the 'object'. The topic is about an object in absence of such ideals such as purpose.

I don't think a beam of energy say 'knows' anything about human purpose.They ‘know’ that the building is of interest to them. -

javi2541997

7.2kNo, I asked where 'this' stops. I never said 'building'. — noAxioms

javi2541997

7.2kNo, I asked where 'this' stops. I never said 'building'. — noAxioms

Are you really sure? ...

Where does the building stop? — noAxioms

Still, purpose is defined by the humans that find utility in the 'object'. The topic is about an object in absence of such ideals such as purpose. — noAxioms

I agree. Human convention defines 'purpose,' and the building exemplifies this. What I don't understand is why you wish to eliminate such principles. As far as I can tell from this thread, most objects and things are defined by human conventions or other categories that make them 'interesting.' Are you arguing that there could be an intriguing object that lacks human ideals?

I don't think a beam of energy say 'knows' anything about human purpose. — noAxioms

Obviously, and I don't think it is necessary to go too far. What I tried to argue is that there are objects which are dependent upon others just for need. The furniture, walls, ceilings, etc. are attached objects to the principal which is the building. Otherwise, where would you put furniture? In middle of the forest? That would be senseless. You claim this is due to human purpose, but I think those 'objects' know the destination of its utility. -

noAxioms

1.7k

noAxioms

1.7k

Yes. The whole point ot the topic is about when human demarcation is absent.Are you really sure? ... — javi2541997

This was a different context, meant to illustrate that even when a human convention is invoked, the demarcation is still never precisely defined.Where does the building stop? — noAxioms

I didn't want to eliminate them. I wanted to show where they stand in the hierarchy of levels.What I don't understand is why you wish to eliminate such principles.

BTW, the heirarchy (ideal mind bio chem phys math) is kind of a human one. Different paths can lead to 'building' being meaningful, such as (ideal, cognitive entity, computation, electrical, physics, math) which means that our AI would probably be able to demark a building despite it not being a biological mind.

I meant to look for one in reality. Found plenty in fiction. The fact that they're only in fiction shows that such concepts have no actual physical basis, and 2) people readily accept/presume otherwise.Are you arguing that there could be an intriguing object that lacks human ideals?

Yes, obviously, except nobody complains when a beam of energy does exactly that in a fictional story.I don't think a beam of energy say 'knows' anything about human purpose.

— noAxioms

Obviously

But it isn't even furniture without humans to name them so. They serve purpose to humans. Your examples are of human made artifacts, which serve a specific purpose to a human.What I tried to argue is that there are objects which are dependent upon others just for need. The furniture, walls, ceilings, etc. are attached objects to the principal which is the building. Otherwise, where would you put furniture? In middle of the forest?

So at the biological level, there are objects of sorts. Not so much twig say, but maybe 'pollen', which is a natural unit of reproduction to many plants. The beam of light, not being biological, cannot demark one pollen bit, but a different plant (than the one that made it) can. It's not an ideal to the plant, so it serves a physical purpose as an object, and not just as an ideal of an object.

Similarly, DNA constitutes information, perhaps below the biological level and reaching down to the chemical level. This is information (objects of a kind) without being ideals. So there are examples out there.

A sofa 'knows' it is a sofa, or at least where its boundaries are, or that it is useful to humans? in what way does that make sense?I think those 'objects' know the destination of its utility. -

javi2541997

7.2kYes. The whole point of the topic is about when human demarcation is absent. — noAxioms

javi2541997

7.2kYes. The whole point of the topic is about when human demarcation is absent. — noAxioms

:up:

But it isn't even furniture without humans to name them so. They serve purpose to humans. Your examples are of human made artifacts, which serve a specific purpose to a human. — noAxioms

I agree. All of those objects serve a purpose for humans, but I think this is not the main point of my argument. Although they are dependent on human purposes, they are necessarily part of a house. I mean, you would not put a sofa or a fridge in the moon, just as a twig would not flourish randomly in a corridor. We can imagine in the abstract, but I think there should be a basic sense in order to attach things to others. You claim (if I am not mistaken) that their ‘attachment’ serves human purposes, but I still believe they have intrinsic value. I will not light up a candle in the sun. Would you? How will the latter satisfy my purpose?

A sofa 'knows' it is a sofa, or at least where its boundaries are, or that it is useful to humans? in what way does that make sense? — noAxioms

But why should everything be useful to us? Didn’t you ever think of the pure lonely existence of that sofa?

Consider what happens if a nuclear bomb destroys all of human life and leaves only that sofa. Do you believe the sofa will lose its sense since it will no longer meet a human need? -

noAxioms

1.7k

noAxioms

1.7k

I don't get your point at all. Perhaps a summary is in order. Without people,there is no house at all, just a collection of material, not particularly a bounded one either. It's a house only because humans consider it to be one.All of those objects serve a purpose for humans, but I think this is not the main point of my argument. Although they are dependent on human purposes, they are necessarily part of a house. — javi2541997

You use the word 'flourish' in your post, which seems only something that reproduces does (not necessarily a life form). I don't see meaning of that word at lower levels.

And yes,the last candle I lit up was in the sun, just a coincidence

All I'm worried about is what demarks objects in the absence of a name. Calling something a sofa automatically invokes a convention. I am trying to find object in absence of human convention. What use humans have in one object doesn't seem to come into relevance in pursuit of that investigation.Didn’t you ever think of the pure lonely existence of that sofa?

No, I don't think a sofa has a sense of anything. There is still the narrator of the story about the bomb that is giving the object a name. But what if it isn't named at all?Consider what happens if a nuclear bomb destroys all of human life and leaves only that sofa. Do you believe the sofa will lose its sense since it will no longer meet a human need?

Welcome to The Philosophy Forum!

Get involved in philosophical discussions about knowledge, truth, language, consciousness, science, politics, religion, logic and mathematics, art, history, and lots more. No ads, no clutter, and very little agreement — just fascinating conversations.

Categories

- Guest category

- Phil. Writing Challenge - June 2025

- The Lounge

- General Philosophy

- Metaphysics & Epistemology

- Philosophy of Mind

- Ethics

- Political Philosophy

- Philosophy of Art

- Logic & Philosophy of Mathematics

- Philosophy of Religion

- Philosophy of Science

- Philosophy of Language

- Interesting Stuff

- Politics and Current Affairs

- Humanities and Social Sciences

- Science and Technology

- Non-English Discussion

- German Discussion

- Spanish Discussion

- Learning Centre

- Resources

- Books and Papers

- Reading groups

- Questions

- Guest Speakers

- David Pearce

- Massimo Pigliucci

- Debates

- Debate Proposals

- Debate Discussion

- Feedback

- Article submissions

- About TPF

- Help

More Discussions

- Artificial Super intelligence will destroy every thing good in life and that is a good thing.

- Do physical models give a good view in the physical reality?

- Can you imagine a different physical property that is doesn't exist in our current physical universe

- For Kant, does the thing-in-itself represent the limit or the boundary of human knowledge?

- Other sites we like

- Social media

- Terms of Service

- Sign In

- Created with PlushForums

- © 2026 The Philosophy Forum