-

jorndoe

4.2kLet me just run this one by you folk. Not an essay, no proofs, just a perspective, a context.

jorndoe

4.2kLet me just run this one by you folk. Not an essay, no proofs, just a perspective, a context.

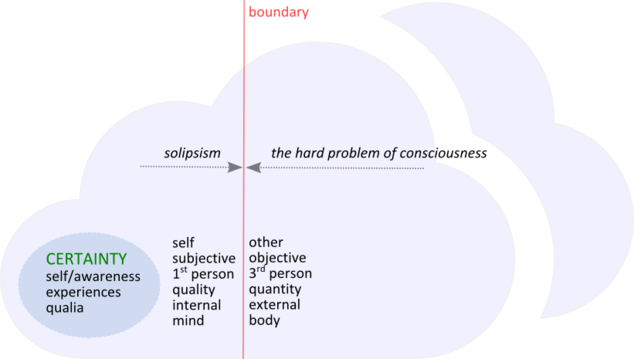

It seems there's broad agreement that solipsism is neither provable nor disprovable, and likewize for a larger, extra-self world, that we're part of.

So, it might be more fruitful to try understanding what kinds of worlds engender solipsism. Is the last person alive a solipsist? I suppose, technically, in a way, though they might not otherwise have been, if their parents also were there for example.

The difficulty with other minds comes about because 1st person experiences are sort of private. Is your red my red? I don't experience your self-awareness, since, well, I'm not you. In fact, I can't — even in principle — not without being you, in which case I'd no longer be me, which is nonsense. Self-awareness is essentially indexical, a kind of self-knowledge, and bound by self-identity.

Why is that a problem anyway? Well, because of certainty, problems of induction, Occam's razor (parsimony), skepticism (doubt), ... Unlike Cartesian "cogito ergo sum", other peoples' self-awarenesses are like noumena, always just over the horizon.

- (Most folk sport some sort of self-awareness. Differentiating introspection and extrospection, cognitive capacity to separate self and other, ability to understand and use a mirror, an inwards awareness of thoughts, feelings, experiences of self, a sense of continuation.)

And so, it seems to be logical worlds — or worlds that engender logical thinking at least — that lead to the problem of solipsism, since it's logic that forms the boundary between (deductive) certainty and uncertainty in the first place.

Take standard (logical) reasoning:

- identity - in particular

- non contradiction

- the excluded middle

- (modus ponens, modus tollens, double negation (introduction))

Now what can you deduce from a self-identity (like p=p) alone? Not much.

Certainty by deduction is logical (and rational), but, as per above, there's no deductive proof of others' self-awareness. Self-identity, as mentioned, is characteristic of self-awareness, and that's (also) to say logical identity. However, given just this identity does not imply much, including the nature or existence of something else.

And so, a sound proof of something extra-self hits mentioned boundary. Thus, solipsism shouldn't be all that surprising, in fact, we should expect something like that to come up. Our world is such that self-identical, logical thinkers can run up against solipsism, as a matter of "safe" reasoning therein. And philosophers sure are infatuated (or even obsessed) with certainty.

Mystery exposed...? -

jorndoe

4.2kAddendum

jorndoe

4.2kAddendum

So, what about reasoning then? Useless posturing? No, of course not. It's not to abandon reasoning, or throw hands in the air in futility, rather the opposite. It's to recognize the difficulties involved in knowledge acquisition; something students of history (of science and philosophy in particular) should know all too well. Common sense, heuristics, careful inductive and abductive reasoning are indispensable for anyone wishing to learn, and that's the natural modus operandi of most healthy individuals in any case. (Outside of philosophy, solipsism is largely pathological, reported by doctors and asylums.)

Numerous philosophical branches have been charged with solipsism, including, but not limited to, Cartesian skepticism (obviously), (pure) phenomenology, subjective idealism (and some other idealisms), postmodernism (when applied in metaphysics). It crops up in numerous places, and is occasionally used argumentatively to deny just about anything, i.e. a rhetorical tactic.

But, in the requisite Wittgensteinian tradition, languages sure help. Regardless of whether or not there are private languages, public languages enable sharing of experiences.

-

Wayfarer

26.2kThe difficulty with other minds comes about because 1st person experiences are sort of private. Is your red my red? I don't experience your self-awareness, since, well, I'm not you. In fact, I can't — even in principle — not without being you, in which case I'd no longer be me, which is nonsense. Self-awareness is essentially indexical, a kind of self-knowledge, and bound by self-identity. — jorndoe

Wayfarer

26.2kThe difficulty with other minds comes about because 1st person experiences are sort of private. Is your red my red? I don't experience your self-awareness, since, well, I'm not you. In fact, I can't — even in principle — not without being you, in which case I'd no longer be me, which is nonsense. Self-awareness is essentially indexical, a kind of self-knowledge, and bound by self-identity. — jorndoe

I think the issue gets too much attention, and it's because of a misreading of Descartes, or perhaps because of some lack in Descartes' development of the implications of the cogito.

I was reading about Husserl's appraisal of Descartes here - worth looking at in this context. The thrust is that whilst the cogito was hugely significant in establishing the foundational role of subjectivity in the definition of knowledge, Descartes' rendering of it asres cogitans - something objectively real - failed to capture its actual function as 'the condition for the possibility of unified experience and as the domain of meaning-constitution'. So subsequent generations, I think, totally misconstrued the implications of Descartes ideas, one of the consequences being the notion that 'first-person knowledge is the only certainty'. I think you can see other ongoing consequences of these problems in 'ghost in the machine' style of critique, which are all centred around the problematic notion of what a 'thinking substance' could possibly be.

Anyway, as I've said on numerous occasions in this connection, 'empathy is the antidote to solipsism'. And why? From a Buddhist perspective, it is because empathy or compassion is really the exchange of self with others. You see as they see, you feel as they feel. So even though it is strictly true that you don't know their experience in the first person, it is to all intents apodictic in much the same way as the cogito is; other beings are as I am, and I am as other beings are. That tends to ameliorate the sense of the otherness of others in a very practical way.

(I also think this has something to do with mirror neutrons, but I haven't really developed that idea. Lovely graphic, by the way.) -

jorndoe

4.2kI think the issue gets too much attention, and it's because of a misreading of Descartes, or perhaps because of some lack in Descartes' development of the implications of the cogito. — Wayfarer

jorndoe

4.2kI think the issue gets too much attention, and it's because of a misreading of Descartes, or perhaps because of some lack in Descartes' development of the implications of the cogito. — Wayfarer

I agree, to an extent at least. It is, however, a philosophical problem, regardless of Descartes.

That said, I think there are some other conundrums that are somewhat related. I'll try to formulate something, if time permits. -

jorndoe

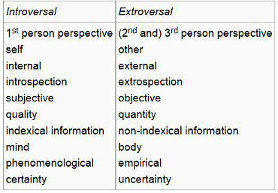

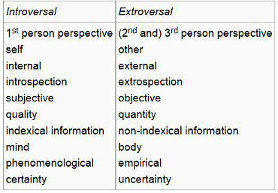

4.2kConsider the following dichotomy, a common categorization of experiences:

jorndoe

4.2kConsider the following dichotomy, a common categorization of experiences:

- Non-identity: Say I have a chat my neighbor. My experiences of my neighbor ≠ my neighbor. (My better half may also experience the neighbor.)

- Identity: Say I have a headache. My experience of the ache = the ache. (My better half don't have my headache (I sure hope not anyway).)

By this categorization,

- hallucination is confusing non-identity for identity, and

- solipsism is confusing identity for non-identity.

Paraphrasing Searle, if anything significant differentiates perception and hallucination, then it must be the perceived.

As in the opening post, non/identity sets the stage for a dichotomizing boundary condition. -

Wayfarer

26.2kMy experiences of my neighbor ≠ my neighbor.

Wayfarer

26.2kMy experiences of my neighbor ≠ my neighbor.

There's my impressions of my neighbour. He might turn out to be something very different to what I thought, without that negating the fact that I know him.

Say I have a headache.

People with amputated limbs have phantom pains, i.e. pains in the non-existent limb. -

jorndoe

4.2k(I've been tricked into North American spelling. Neighbour without the 'u'.) :)

jorndoe

4.2k(I've been tricked into North American spelling. Neighbour without the 'u'.) :)

Your impressions of your neighbor is, or is derived from, your experiences, yes?

Similar to your memories thereof.

None of which are your neighbor, though.

Note, hallucinations themselves do indeed exist.

What makes them hallucinations is just that they're not what they're taken to be.

So I think the categorization holds for phantom pain.

What makes pain "phantom", is confusing non-identity for identity. -

Wayfarer

26.2kI think the question you're exploring is, what is the meaning of 'is' or of 'equals'. When we say A = A, how do we know this is the case. So the argument is, we know what is evident in the first person, in a way that we can't know for other categories of experience.

Wayfarer

26.2kI think the question you're exploring is, what is the meaning of 'is' or of 'equals'. When we say A = A, how do we know this is the case. So the argument is, we know what is evident in the first person, in a way that we can't know for other categories of experience.

As I said in the first post, this seems to be a consequence of a rather literalistic interpretation of 'I think, therefore I am'. But notice that Descartes then went on to argue for the certain nature of particular elements of experience, namely, the 'clear and distinct ideas' which provides for certainty across a whole range of knowledge (as per here).

All that said, there is a sense in which we knowledge is in some important way provisional - which is reflected in the understanding that scientific hypotheses are provisional and liable to being superseded at any time. So as per Kant, we could say that we only have knowledge of appearances or phenomena; however, within that constraint, such knowledge might nevertheless be reliable or practically indubitable. -

jorndoe

4.2k

jorndoe

4.2k

Thanks for the comments.

I'm headed in a different direction. (Descartes was just an example.)

Identity can be the propositional tautology or ontological (whatever exists is self-identical).

The solipsism thing in the opening post exposes a dichotomy originating from identity, or at least that's the working hypothesis for investigation, supported by the opening post.

The overall idea is that identity also leads to other, somewhat similar dichotomies, with whatever boundaries.

Going by the opening post, 1st person experiences do not derive others' self-awarenesses, and are thus incomplete. Going by the hard problem of consciousness, physicalism (or whatever) does not derive qualia, and is thus considered incomplete.

If the hypothesis holds — that these various "disconnects" or boundaries are simply due to identity — then what of our predicament? Maybe the world is "dichotomized by identity" (not lobotomized, mind you :)), with these intrinsical boundaries?

Anyway, I'll try to give it some more thought, and post, when time permits. -

jorndoe

4.2kOkiedokie, let me resume a bit with this stuff; first a summary of identity, because the dichotomy already shows up here.

jorndoe

4.2kOkiedokie, let me resume a bit with this stuff; first a summary of identity, because the dichotomy already shows up here.

There are two important senses of identity — ontological and logical — encompassed by this 1st of the 3 classic laws of thought.

Ontological identity simply states that anything that exists is self-identical. This is both self-evident and intuitive, allowing us to talk about and differentiate things, and usually taken to be fundamental.

Logical identity is technically a formalized axiom, a rule that pertains to propositions and reasoning (tautology, x=x, p⇔p), and can be a more linguistic expression of ontological identity. The excluded middle (the 3rd law), along with its complement, non-contradiction (the 2nd law), are correlates of identity. Because identity intellectually partitions the world into exactly two parts, like "self" and "other", it creates a dichotomy wherein the two parts are mutually exclusive and jointly exhaustive. Non-contradiction is merely an expression of the mutually exclusive aspect of that dichotomy, and the excluded middle is an expression of its jointly exhaustive aspect.

The two senses of identity are intimately related, and somewhat interchangeable depending on context.

Whatever is, is. — Bertrand Russell (The Problems of Philosophy, Chapter VII) -

jorndoe

4.2kMore on those pesky dichotomies and dualities and what-not

jorndoe

4.2kMore on those pesky dichotomies and dualities and what-not

At a glance, it seems there are a few somewhat related dichotomies, that crop up in various contexts.

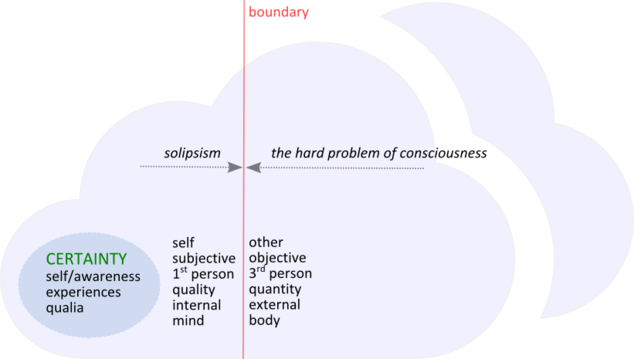

In terms of solipsism, or parsimonious skepticism, a similar dichotomy could perhaps be expressed as existential certainty versus uncertainty.

Substance dualism is out, rather identity itself creates a different sort of apparent dualism.

The Cartesian cut — res cogitans (thinking substance, mental) versus res extensa (extended substance, material) — is an expression of a duality like the dichotomy above.

By substance, Descartes meant an ontologically independent, real thing.

In the context here, res cogitans is instead subject to an inwards self-blindness (possibly tending towards "soul" ideation or mysticism), and the identity boundary outwards.

This account is thus is compatible with monism of some sort, and there isn't anything in particular preventing an "artificial" organism from experiencing the world akin to us. -

jorndoe

4.2kThe Hard Problem of Consciousness

jorndoe

4.2kThe Hard Problem of Consciousness

The Chalmers style mind-body problem derives from a dichotomy:

- the format of 1st person phenomenological experiences, qualia (introversal)

- the 2nd/3rd person world of objects, processes, bodies, brains, etc (extroversal)

And the apparent intractability:

- 1st person experiences do not derive others' self-awarenesses and such, and are thus incomplete — solipsism

- physicalism (or whatever) does not derive qualia, and is thus considered incomplete — the hard problem of consciousness

From mind to body:

the leap from the mental process to a somatic innervation — hysterical conversion — which can never be fully comprehensible to us — Sigmund Freud (Notes Upon a Case of Obsessional Neurosis)the puzzling leap from the mental to the physical — Sigmund Freud (Introduction to Psychoanalysis)

From body to mind:

412. The feeling of an unbridgeable gulf between consciousness and brain-process: how does it come about that this does not come into the consideration of our ordinary life? This idea of a difference in kind is accompanied by slight giddiness — which occurs when we are performing a piece of logical slight-of-hand. (The same giddiness attacks us when we think of certain theorems in set theory.) When does this feeling occur in the present case? It is when I, for example, turn my attention in a particular way on to my own consciousness, and, astonished, say to myself: THIS is supposed to be produced by a process in the brain! — as it were clutching my forehead. — Ludwig Wittgenstein (Philosophical Investigations, Part I)

So we have a context where solipsism and the hard problem of consciousness comprise yet another dichotomy. -

jorndoe

4.2kLeap to Hypothesis

jorndoe

4.2kLeap to Hypothesis

Central to these musings is identity, be it as reasoning (logical), or worldly structure (ontological).

The hypothesis can now be expressed, in brief, as: what separates introversal and extroversal is simply onto/logical identity.

- We're subject to a dichotomizing boundary condition, as a result of identity.

- A number of recurring dichotomies are partitioned by similar boundaries, where the halves of each dichotomy does not entail the other.

- Along with solipsism, the mind-body problem expresses an aspect of said boundary.

Anything essentially self-referential, remain introversially stuck. And, like indexical information cannot be derived from non-indexical information, the extroversial does not imply the introversial. Where introversial identity (post 5 above) is phenomenological alone, extroversial non-identity (post 5 above) is also empirical.

As per Freud and Wittgenstein above, I surmise one of the ways these conundrums have come up, in philosophy, originally, is the difficulty in grasping how something like one's own 1st person experiences could come about, from the world of 3rd person perspective things. That is, how on Earth can the more introspective world of experiences, thoughts, qualia, etc, come about from the extrospective spatiotemporal world of objects, processes, etc? Limitations of introspection compound the difficulty.

If the hypothesis holds (that the "disconnect" or boundary is due to basic identity), then we may have to contend with our predicament.

Incidentally, this emphasizes a need for strong epistemic standards, i.e. justification. -

mcdoodle

1.1kIf the hypothesis holds (that the "disconnect" or boundary is due to basic identity), then we may have to contend with our predicament. — jorndoe

mcdoodle

1.1kIf the hypothesis holds (that the "disconnect" or boundary is due to basic identity), then we may have to contend with our predicament. — jorndoe

Is there such a boundary? Humans, as compared to their nearest animal relatives, study each other a lot. I have very particular ways of talking about my pain, but if I talk to a doctor, they are likely to understand much more about what's going on in my body than me.

My wife says she knows when I'm unhappy about something because of certain physical gestures I make. Most people 'know' things about their intimate friends or relatives in this way, 'better than I know myself'.

Also, I think it's a category mistake to infer issues about 'personal identity' from ideas about 'identity' as ontology. The same word is in the phrase, so some similar factors apply, but a lot of different factors do too. Things that are identical to each other don't say 'I' or 'me', or indeed anything at all; to my mind this is a key difference between the notion of their identity and my notion of yours or mine. -

jorndoe

4.2kHey mcdoodle, thanks for the comments.

jorndoe

4.2kHey mcdoodle, thanks for the comments.

The mentioned "boundary" (in lack of a better word), is inherited more or less directly from solipsism and Chalmers' hard problem of consciousness. (It's not so much a brick wall everyone carries around.) :)

A focus on one's own mind is self-reference, and thus "bound" by self-identity.

But then (a bit unexpectedly) it seemed that such "bounds" appeared in a few places.

This angle does not "solve" these things as such, but just contextualizes them in a kind of basic way.

In this particular context, a notion of personal identity only goes as far as mind and body.

(Personality is something else, like psychology, traits and behaviors and such.)

Hmm.. Your examples (doctor, wife) may actually exemplify the idea, need more morning coffee to tell.

By the way, I typed the stuff into a wiki page elsewhere; may be formulated/organized better there; sending you the link.

-

jorndoe

4.2kAssume I've gotten myself a headache; I'm sure most can relate, unfortunately.

jorndoe

4.2kAssume I've gotten myself a headache; I'm sure most can relate, unfortunately.

No aspirin at hand. Instead I go scan myself, fMRI or whatever the latest may be, doesn't really matter.

I now have two different angles, the experience of the ache, and a visual overview of my gray matter (need not be visual alone).

I'd say only the angles differ, in an ontological sense, so what makes them different?

(Does anyone really doubt that feeling hungry means the body needs replenishment?)

Someone elsewhere asked (not my quote):

Does a neurophilosopher who performs an awake surgery on his own brain to investigate the body-mind problem carry out a thought experiment or scientific research?

Understanding the scan, in this context, would converge on understanding the headache; a straight identity may not be readily available (or deducible).

The headache itself is part of my self-experience, or, put simpler, just part of myself — bound by (ontological) self-identity, like self-reference, regardless of any scans or whatever else.

Others cannot have my headaches, but others can check out the scans. -

mcdoodle

1.1kOthers can look at you when you're busy with something (I have experience of this, I get cluster headaches) and say to you, 'I think you're getting a headache'. They recognise familar signs. Then they make allowances in chat with you for the fact that you're always grouchy when you have a headache.

mcdoodle

1.1kOthers can look at you when you're busy with something (I have experience of this, I get cluster headaches) and say to you, 'I think you're getting a headache'. They recognise familar signs. Then they make allowances in chat with you for the fact that you're always grouchy when you have a headache.

But perhaps all I'm saying is that the boundary is permeable, I'm not sure myself. How do we understand each other? I have recently read some stuff by Karsten Steuber, he has interesting things to say. One can start with the Stanford entry on Empathy which he wrote: http://plato.stanford.edu/entries/empathy/ -

jorndoe

4.2kTyped the musings in over on wordpress, with a bit more detail:

jorndoe

4.2kTyped the musings in over on wordpress, with a bit more detail:

https://aniarasite.wordpress.com/yet-another-mind-body-hypothesis/

Comments welcome of course. -

mcdoodle

1.1kHi jorn.

mcdoodle

1.1kHi jorn.

...the difficulty in grasping how something like one’s own 1st person experiences could come about, from the world of 3rd person perspective. — wordpress blog

First, you have to explain the converse. I know who I am, but what is this 'world' of which you speak? How, from an infantile almost undifferentiated world of me-ness (if there is such a thing) comes this so-called 3rd person perspective? At least, how come the differentiation? My new pal Heidegger (well I've read 'Being and Time' a second time and seem to understand it) argues we begin with ourselves, our own being, Dasein, and stuff that's present or ready.

I feel you have to put your arguments about this first. Otherwise you just assume some sort of naive realism without saying that you do, and leave people like me behind. I think of human identity as a social question. I can masquerade as several different people, in different places and times, but the modern world of Statism and surveillance wants me to be just one. Dammit, they're even trying to stop me using cash so they can keep track of the unitary me. -

jorndoe

4.2kHi mcdoodle (apologies for my absence).

jorndoe

4.2kHi mcdoodle (apologies for my absence).

Yes, you're right, my rendition definitely tend towards realism of some sort (perhaps physicalism).

There may be other renditions.

It was mostly a matter of contextualizing Chalmers' hard problem and solipsism, or that's how it ended up anyway, with the basic explanatory assumption being onto/logical identity. -

BC

14.2kMy new pal Heidegger (well I've read 'Being and Time' a second time and seem to understand it) argues we begin with ourselves, our own being, Dasein, and stuff that's present or ready. — mcdoodle

BC

14.2kMy new pal Heidegger (well I've read 'Being and Time' a second time and seem to understand it) argues we begin with ourselves, our own being, Dasein, and stuff that's present or ready. — mcdoodle

I think that's right. Some research into early childhood experience (the first few months) indicates that babies come armed with some built in assumptions about the world. There is no reason to be horrified by this -- we are, presumably, the product of evolution and it some skills seem to wired into the very young of a number of species.

So, one of the built in assumptions seems to be an understanding of a basic fact of gravity: dropped things fall. Here's a lovely nursery rhyme, introducing the baby to gravity and death.

Rock a-bye baby in the tree top

when the wind blows the cradle will rock

if the bough breaks, the cradle will fall

and down will come cradle, baby, and all.

Lovely. Telling babies about dying is dirty work but somebody has to do it. Who else but Mommy? Anyway, when you show a baby something (like a bright red ball) and drop it, the baby expects it to fall--judging by his eye movements and reaction. If you show the baby a bright red balloon filled with helium and let go, the ball rises to the ceiling. According to the researchers, the babies were "shocked". Shocked! Rising objects did not conform to their experience.

Babies come with personality and intellectual predispositions, and a few dozen blank slates just waiting to be written on in a certain way--like picking up all of the languages, social cues, and so on that they are and will be surrounded with.

Welcome to The Philosophy Forum!

Get involved in philosophical discussions about knowledge, truth, language, consciousness, science, politics, religion, logic and mathematics, art, history, and lots more. No ads, no clutter, and very little agreement — just fascinating conversations.

Categories

- Guest category

- Phil. Writing Challenge - June 2025

- The Lounge

- General Philosophy

- Metaphysics & Epistemology

- Philosophy of Mind

- Ethics

- Political Philosophy

- Philosophy of Art

- Logic & Philosophy of Mathematics

- Philosophy of Religion

- Philosophy of Science

- Philosophy of Language

- Interesting Stuff

- Politics and Current Affairs

- Humanities and Social Sciences

- Science and Technology

- Non-English Discussion

- German Discussion

- Spanish Discussion

- Learning Centre

- Resources

- Books and Papers

- Reading groups

- Questions

- Guest Speakers

- David Pearce

- Massimo Pigliucci

- Debates

- Debate Proposals

- Debate Discussion

- Feedback

- Article submissions

- About TPF

- Help

More Discussions

- Other sites we like

- Social media

- Terms of Service

- Sign In

- Created with PlushForums

- © 2026 The Philosophy Forum