-

Wayfarer

26.1kLike, do people need to accept your specific philosophical ideal in order to be valued as a contributor? Is not even my questioning of certain ideas a contributing factor on a philosophy forum? Sounds a bit weird to imply a lack of contribution in that way? — Christoffer

Wayfarer

26.1kLike, do people need to accept your specific philosophical ideal in order to be valued as a contributor? Is not even my questioning of certain ideas a contributing factor on a philosophy forum? Sounds a bit weird to imply a lack of contribution in that way? — Christoffer

Questioning is surely a major part of philosophy, but I don't know if you yourself realise how embedded you are in the materialist mindset. I'm not trying to be personal about it - after all, I don't know you - but you take for granted a way of seeing the world which I think is inimical to philosophy per se, which has an ineliminably ethical aspect. I mean, in your analysis, it is simply assumed that religion only ever *is* an opiate, a pain-killing illusion. I have devoted considerable time to Buddhist studies, and there is no way you could mistake Buddhist praxis as 'seeking comfort' or 'comforting illusions'. Without going in to too much detail, the principle involved is obtaining insight into the causes of suffering and cutting it at the root, which (it is said) opens up horizons of being that remain unknown to the regular run of mankind. But it is a renunciate philosophy, and creature comforts are something Buddhists have to learn to live without (a virtue which has generally escaped me).

Regarding scientism and nihilism I don't see how you can avoid it with the stance you take. The scientific mindset revolves around reduction to mathematical simples. That is what makes it so powerful. It has arrived at a method of quantization which allows it to marry mathematical logic with prediction and analysis by identifying solely those aspects of phenomena which are amenable to that method. This is the analysis of, for example, Thomas Nagel's book The View from Nowhere. But as Nagel eloquently points out in many of his other works, this is at the cost of excluding from consideration the nature of lived experience. It is also the root of the argument over the 'problem of consciousness', as David Chalmer's points out, because consciousness - our sense of who we are - is not amenable to quantitative analysis. So it produces a kind of one-dimensional existence, in which the qualitative axis has been omitted and ignored, to the point where even its existence is routinely denied.

I've never bought Nietszche's 'death of God'. Time Magazine published a cover story on it which I read aged about 11 or 12. Besides, as David Bentley Hart points out, it is not a hymn of atheist triumphalism. What if there really is a dimension to existence which is pointed to, however inadequately, in the various religious traditions of the world? Your conviction that it can only be empty words mirrors the certainty of religous dogma to the opposite effect. Religious philosophies are universal across culture and history, and show no sign of fading away, Nietszche's proclamation notwithstanding.

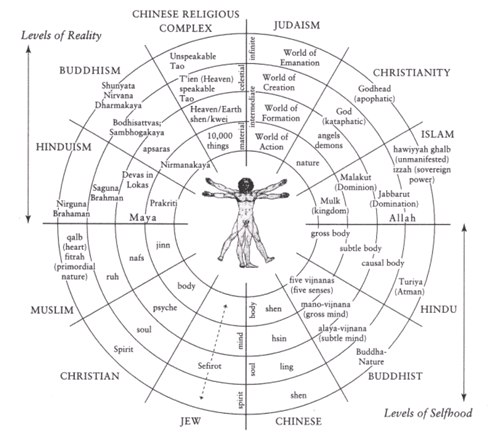

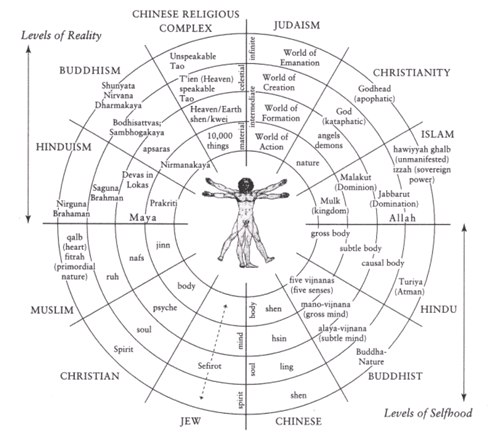

Graphic by Huston Smith

I see the role of renunciate philosophies as being especially crucial in today's world, because consumption obviously has to be drastically curtailed. It is a known fact that human consumption overshoots the Earth's productive capacity and that we are approaching many forms of economic and environmental catastrophe. Whilst science will be absolutely crucial in dealing with all of that, a mindset based on consumption and material pleasure surely can only ever be an impediment to dealing with it. But what alternative does our culture provide? It has rejected or dismantled the idea of virtue as being tied to quality of character and purity of vision. After all, there's nothing to see, right? -

Christoffer

2.5k

Christoffer

2.5k

I thank you for a well put argument. I see your perspective, yet the core issue I have is that since we can only rely on some kind of evidence for a collective understanding, I can only formulate my world view on what we can actually prove or at least speculate as logical based on facts as we define facts. That doesn't render meaningful experience as dismissable, only that I cannot accept ideas and theories when I have knowledge that counters it. If I'm presented with a concept that I can clearly see a solution in psychology explaining it better, then the most likely explanation of said phenomena is the psychological one. And the more I learn, the more perspectives I learn, the less I can summarize anything in any other way than through a holistic perspective that incorporates all of them. What I find problematic in religious perspectives is the random claims of, in their view, factual concepts that only works within its own framework and often affect the ability to have an open mind, to the extent of sometimes radicalize people into harmful acts. Within it, all makes sense, but requires ignorance and denial of a large part of what we know about the world, universe and life. I cannot dismiss that baggage and I cannot dismiss evidence of psychological processes connected to religious experiences that show how they form and develop.

but I don't know if you yourself realise how embedded you are in the materialist mindset. — Wayfarer

It depends. I'm not a reductionist but more in line with emergentism. Emergent behaviors of complex systems. These cannot be explained by simple reductionism and somewhat transcend pure materialism.

But yes, I do not accept supernatural explanations since I have yet to be presented any evidence that supports it. And the more I learn the more inputs I have to explain a phenomena by other means than the supernatural. And the process proves itself over and over. The more we prove of natural phenomenas the less supernatural things get.

You push these ideas that I'm not doing philosophy, but yet, I am. To hold a firm stance within philosophy is nothing strange. I have this stance and I argue for it and if you tell me an argument that can logically undermine my conclusions, then I'm open to discuss adjustments. But I cannot dismiss the philosophical position I have on the mere fact that you disagree with me and it does not make me less of a philosopher when I require much better support in evidence for counter claims to my conclusions. In the end it becomes almost like you point out that there is experiences unexplained and therefor I am wrong, which isn't how this works. You cannot use the unexplained as evidence for my framework being broken. The experience is simply an experience that exist, yet to be explained. It does not require religion.

you take for granted a way of seeing the world which I think is inimical to philosophy per se — Wayfarer

You frame it as such, maybe because you feel it is a threat to your own position in philosophy, that doesn't render it objectively harmful, which I feel is a bit over the top in regards to what I've written. That feels more like expressing a need to downplay my position and paint it as dangerous in order to remove the perspective all-together. I don't understand this at all since I find this much more hostile than how you frame my writing. If you find it hostile, as I said, might it just be so because it is in such direct contrast to the position you hold close to heart? But isn't philosophy actually about clashing such positions together in discourse without hostility? This way of framing my writing seems more like a knee-jerk reaction to what I write rather than engaging philosophically? However, you also present a thought through counter argument so I'm not really sure how to interpret what you mean by all of that?

in your analysis, it is simply assumed that religion only ever *is* an opiate, a pain-killing illusion. I have devoted considerable time to Buddhist studies, and there is no way you could mistake Buddhist praxis as 'seeking comfort' or 'comforting illusions'. — Wayfarer

Not an opiate, for some it is, but that's not what I mean by comfort. Comfort is simply what holds back the sheer terror of the experience of a meaningless existence. I require such comfort as well, so does all people. Without it we would fall into utter despair. What I underscore is that most people experience panic and swan dives right into whatever comfort there is as fast as they can, not even having time knowing that they do so. Most people just accept anything that turns their mind away from this dread and fear boiling underneath their experience.

What I'm advocating for is to align everything towards an experience that rejects illusions and fantasy but can still reach such comforting results. Because there's too much baggage that comes with most of religion.

What Buddhism is about is still such a process. It starts with the painful questions about our existence and evolves into an exploration of ideas to comfort against that sense of darkness and lack of meaning. The reason to begin the journey is always the same, for all. That is not an opiate, that is a strategy against the experience of meaninglessness. A journey for meaning can be painful and hard, but against the utter despair of meaninglessness it is still a comfort.

And my position in this is that there's a gradient of the ability to handle this, from person to person. Some, most people, jump straight into it as an opiate against the dread, while some explore other means of experiences and exploration. If the opiate is on one end I just happen to be on the opposite end, rejecting anything that doesn't logically follow the universe as it is and presents itself to us. What is a good and bad strategy has nothing to do with it really. However, I personally believe that we need to follow science more than illusions and fantasy as the defining foundation for mankind as a collective, because the part that is fantasy is often prone to cause unseen consequences that most often does not have mankind's best intention in mind. That does not remove the need for experiences with fantasy and illusions, only that our experiences with such can remain in fiction and still have just as important and mythological impact on our experience.

the principle involved is obtaining insight into the causes of suffering and cutting it at the root, which (it is said) opens up horizons of being that remain unknown to the regular run of mankind. — Wayfarer

How is that different from experiences featuring LSD or Psilocybin? From the research going on into therapy with such substances, it is becoming known that they cut off the negative emotions, the suffering durring a session, letting the patient explore the roots of their suffering in a much more exploratory way. An intense form of induced meditation. And as many seem to point out, there are patterns similar to deep meditation. Why would one then need Buddhism as a religion when the praxis of meditation can be detached from it? My point is that there seem to exist an inability to look at many practices in isolation from many different religions. Key point being that the explorations in Buddhist practices do not require the whole religious package of Buddhism. Just as a prayer in Christianity could be explored without the religious whole.

I think it's within this that makes it problematic to frame me as a pure materialist. I need evidence and logic in explaining the universe and life, but the experiences we have as humans still is an emergent process that has extreme complexity and function only based on the rules, both known and yet unknown, of our psychology. In the end we may require a spiritual kind of experience in order to actually function as a species, and it is my conviction that we can develop such things without the baggage of religion.

But we've yet to enter such a phase in history as the current state of humanity is about replacing religion with materialistic ideologies and ways of life. It's when humanity realizes the futility of doing so that we may enter a phase in which we seek experience beyond the materialistic and religious.

Regarding scientism and nihilism I don't see how you can avoid it with the stance you take. The scientific mindset revolves around reduction to mathematical simples — Wayfarer

That is a simplification. I don't see the need for illusions and fantasy to be actual and real in order to experience wonder. Storytelling, art, music, experiencing nature as it is, experiencing love and other people. While there is no objective meaning, we build meaning for ourselves. Living as a nihilist has problems functioning together with the ability to produce meaning and experiencing such meaning actually makes it an objective part of reality for us as humans, the experience is a provable process. The difference, however, is that this meaning is created by our hands, by our ideas, not framed as meaning through illusions and fantasies viewed upon as facts that negatively influence our ability to understand reality for what it is or most likely is.

Living as a nihilist is for those who've yet to land in a functioning comfort framework of existence outside of religious beliefs. Those stuck in nihilism have no guidance, because, there really is no common one in existence. Today, we either have religion and if not that we have cults, addiction or materialistic life-styles. There's very little guidance and philosophies out there about this next step from nihilism toward a sense of meaning and that's what I'm interested in exploring and formulating. I would say that Camus may be the closest to it, but I still think it lacks inclusion of all human complexity.

I truly don't have any beliefs in gods or the supernatural. Yet I feel no nihilism in my bones. I don't act out such nihilism and I instead appreciate and love life. Am I not then a walking contradiction to your point? If I can't avoid it, how can I then not be acting as a nihilist and at the same time reject religious beliefs? I think you ignore other dimensions to this.

But as Nagel eloquently points out in many of his other works, this is at the cost of excluding from consideration the nature of lived experience. — Wayfarer

And I would say that it is possible to include the nature of lived experience without requiring religious beliefs. A rejection of religious baggage is to acknowledge the practices in religion separated from the fantasies. To follow science, facts and evidence does not equal a rejection of human meaningful experiences. Only a rejection of the act of concluding unsupported claims as something factual and specific based solely on religious concepts and inventions. We can still have profound experiences without that.

So it produces a kind of one-dimensional existence — Wayfarer

In my perspective, as would be considered to exist in that kind of existence, I don't experience it one-dimensional. I'd argue that people stuck in religious belief are unable to grasp the experience of a non-believer who still live life full of meaning and profound experience of living. The reason they're unable isn't because they're stupid or anything like that, but that the perspective of a believer is so far away from the non-believer that it reshapes how they experience reality. I would say it's easier for a non-believer to imagine themselves in the shoes of a believer than the other way around. Because if you are fully convinced you have the answers to why things are as they are, you are unable to imagine an experience not having those answers, but a person who accept only what we already know and accept that there are answers we've yet to find, they aren't bound to such biases. In essence, It's easier to imagine having a bias than to be a slave to one imagining being without.

I've never bought Nietszche's 'death of God'. Time Magazine published a cover story on it which I read aged about 11 or 12. — Wayfarer

Is that the extent of your knowledge of that concept? A Time Magazine story?

The death of god is about how modernity removes much of the need for religion and a belief in God. The concept's end point is to warn about nihilism as the world transitions more away from religion. But what gets lost is what he's actually warning about and it's about the desperate replacements for God. He couldn't have predicted how the world looks today, but he predicted how our modern culture basically replaced the church and God with the free market, materialistic life-style.

What if there really is a dimension to existence which is pointed to, however inadequately, in the various religious traditions of the world? — Wayfarer

That dimension of existence would not require the religions themselves. You don't need the entire forest to have a tree. You can study tree in itself. And then you've really just entered the science of researching the validity of such a dimension and the journey towards that enlightenment. Why is that similar journey less profound? This "What if" is not enough to argue for the need of religion itself since your goal seem to have nothing to do with religion, it has to do with purely a focus on our experiences. As I've mentioned with LSD, when I've heard people describing their experience and the experience of life after it, that sounds like a profound religious experience, without the need for religious beliefs and fantasies claimed as facts. Why would such induced experience be considered less profound or meaningful to these people? Because it's not within the framework of a religion? Or is it just that we've yet to actually looked into such experiences outside of the framework of religious beliefs?

Your conviction that it can only be empty words mirrors the certainty of religous dogma to the opposite effect. Religious philosophies are universal across culture and history, and show no sign of fading away, Nietszche's proclamation notwithstanding. — Wayfarer

Here I feel you strawman my position a bit by making a simplification of it.

And the fact that religion exist universally across culture and history can easily be explained by analyzing human behavior. What the psychology is for people trying to figure out the world around them in ancient times. How so many have sun gods because... well, it's the most profound thing to witness in a time when there are no answers to anything that happens. The similar experience that people have globally by living on the same planet with similar conditions, would of course produce similarities across the religions that forms.

And once again, it's not fading away because its being replaced by something else (which is closer to what Nietzsche meant). And we can see it in the modern world. The fact that it doesn't fade away only supports what I've been saying, that the desperation into meaning makes it close to impossible for most people to find any alternatives to what we already have, as the journey towards such alternatives demands more work.

I see the role of renunciate philosophies as being especially crucial in today's world, because consumption obviously has to be drastically curtailed. — Wayfarer

I agree, but that doesn't require the baggage of religious beliefs. Why cannot such life-styles and experiences be lived accordingly without having to accept a deity, God, pantheon or made up concepts of existence?

My position is that we can. And without the baggage we skip the risk of skewing people's perspective of our collective physical existence that can end up in, as has happened so many times in history, war and misery. The only reason for the world looking like it does today is because many people have replaced religion with the modern condition and materialistic ideologies. Going back to religion isn't the answer, that would just put us back where we left off and wouldn't really solve the core issue.

But what alternative does our culture provide? — Wayfarer

Maybe we're not there yet, maybe such guidance can't be easily found? Maybe that's what my philosophical position is all about when it comes to this topic? All I can see is that the tired old battle between religious believers and non-believers continue on a shallow level in which that's the only binary discourse that can be heard out loud in society. So when I try to talk about this topic I get shunned into the usual corner. If that happens to all of us trying to actually explore such alternatives, then of course those explorations won't be easily spotted in society.

Our internet algorithms have radicalized our brains to only function on binary assumptions about everything, so a non-believer becomes some kind of zealot of nihilism.

But my position is anything but that. I value exploring our experiences, I value the importance of practices that can be found in rituals, I value all things in religions but reject the claims religion makes about reality that is then acted upon as facts. I reject the need for religious belief when exploring meaning and purpose. Because the beliefs easily shifts into being facts these people believe in, which skews a collective understanding of reality and easily promotes ridiculous conflicts over such "facts", often with deadly outcomes. -

Wayfarer

26.1kYou push these ideas that I'm not doing philosophy, but yet, I am — Christoffer

Wayfarer

26.1kYou push these ideas that I'm not doing philosophy, but yet, I am — Christoffer

And thanks for your well-considered reply. I will try and keep my response brief as possible.

Not you, in particular, but our culture in general. Lloyd Gerson, who is a Platonist scholar, has a book Platonism and Naturalism: the Possibility of Philosophy. It's a pretty specialist text, but his argument is that Philosophy just is platonism, and that if you deny Platonism, there is no conceptual space for philosophy proper. And, he says, Platonism is irreconciliable with naturalism, which is the mainstream view by default.

I think naturalists tend to turn the kinds of dialectical skills that philosophy has inculcated into our culture against philosophy proper. Daniel Dennett is an example. His more radical books, like Darwin's Dangerous Idea, say that evolutionary theory is like a 'universal acid' that dissolves the container that tries to hold it - that 'container' being Western culture, and one of the things being dissolved, philosophy as philosophers have always understood it.

I can only formulate my world view on what we can actually prove or at least speculate as logical based on facts as we define facts. — Christoffer

We generally define facts scientifically, but existential issues are not necessarily tractable to scientific analysis.

What Buddhism is about is still such a process. It starts with the painful questions about our existence and evolves into an exploration of ideas to comfort against that sense of darkness and lack of meaning. — Christoffer

Not true. It is not about 'ideas' at all. It is about a hard-won transformative insight.

I personally believe that we need to follow science more than illusions and fantasy — Christoffer

So how can you deny the accusation of 'scientism' on the back of statements like this?

What I'm advocating for is to align everything towards an experience that rejects illusions and fantasy but can still reach such comforting results — Christoffer

What 'comforting results' are you referring to? If the illusions of religion are put aside, then what constitutes a real solution to the predicaments of human existence, other than comfort and standard of living?

the fact that religion exist universally across culture and history can easily be explained by analyzing human behavior — Christoffer

Which is reductionist, 'explaining away'. I have studied religion through anthropological, sociological and psychological perspectives in comparative religion, but it's not reducible to those categories, even if they provide very useful perspectives.

I cannot accept ideas and theories when I have knowledge that counters it. — Christoffer

All due respect, I don't believe you have 'knowledge that counters it'. What you have is a firm conviction. -

Christoffer

2.5kNot you, in particular, but our culture in general. Lloyd Gerson, who is a Platonist scholar, has a book Platonism and Naturalism: the Possibility of Philosophy. It's a pretty specialist text, but his argument is that Philosophy just is platonism, and that if you deny Platonism, there is no conceptual space for philosophy proper. And, he says, Platonism is irreconciliable with naturalism, which is the mainstream view by default.

Christoffer

2.5kNot you, in particular, but our culture in general. Lloyd Gerson, who is a Platonist scholar, has a book Platonism and Naturalism: the Possibility of Philosophy. It's a pretty specialist text, but his argument is that Philosophy just is platonism, and that if you deny Platonism, there is no conceptual space for philosophy proper. And, he says, Platonism is irreconciliable with naturalism, which is the mainstream view by default.

I think naturalists tend to turn the kinds of dialectical skills that philosophy has inculcated into our culture against philosophy proper. Daniel Dennett is an example. His more radical books, like Darwin's Dangerous Idea, say that evolutionary theory is like a 'universal acid' that dissolves the container that tries to hold it - that 'container' being Western culture, and one of the things being dissolved, philosophy as philosophers have always understood it. — Wayfarer

I think that's taking it too far. Contemporary philosophy, at least how it appears today, exists right at the edge of science. The difference today is that science has forced philosophy to focus even more on a composition of logic and rational reasoning. I.e there's less room for the purely speculative and the things that are speculative still requires a rational component.

While I do think that its problematic for philosophy to drive wild concepts in metaphysics due to how much more effective science is in that area, we still have areas of thought that need philosophy. Ethics is still very much alive and I think the main area for philosophy today has to do with our place in the universe, meaning, how we live in an ever growing explained universe.

With just how much philosophy has changed the last two hundred years, it may just be that philosophy goes through the same tidal shifts as the rest of the world, changing faster and faster. But there's a difference to concluding something dead and concluding something changing or shifting.

We generally define facts scientifically, but existential issues are not necessarily tractable to scientific analysis — Wayfarer

Our personal experience may not, but we can explain more and more of the roots of our emotions and components of our mind and body generating experiences. And some of those factors are root causes of some existential experiences. As an example, that the existential dread we feel may be something we can never overcome and that comfort against it (as I described it) is vitally required for us to function as a human consciousness. If that is the case, how do we deal with that without hiding truths from people or fall into addictive replacements like materialistic life-styles?

How I see it, there's a lot more than people seem to realize, that can be explained utilizing a combination of different scientific areas for a holistic explanation of a phenomena. It's easy to look at a specific and isolated field in science and conclude it fully unable to explain something, but when combining many fields together there are logical conclusions that start to emerge. As I see it, this should be the role of contemporary philosophy. Scientists to be specialists, philosophers to be generalists.

Not true. It is not about 'ideas' at all. It is about a hard-won transformative insight. — Wayfarer

I meant in the context of the discussion. The reason for its existence still emerge out of those questions. The rise of any religion starts by the unknown trying to be known by man. But it extends beyond religion, it's a core driving force of our consciousness. The unexplained scares us and we comfort ourselves by trying to explain it. But even the act of finding harmony with not explaining it is still part of the same process of dealing with it. What I meant here boils down to a simple rhetorical question of, how did Buddhism begin, or rather "why" did it begin?

So how can you deny the accusation of 'scientism' on the back of statements like this? — Wayfarer

Because scientism have problems with handling holistic speculation, even if those speculations are rooted in rational logic. I.e scientism has problems coexisting even with contemporary philosophy. It's too rigid. It also does not function well with emergentist conclusions, even if emergentism is a large part of many fields of science. Because scientism is largely functioning on reductionism and a specialist approach, not holistic reasoning.

What I meant by that statement is that if I say that we should handle society and our collective space based on scientific conclusions, I mean that we should not let religious claims define our world. For instance, laws in society. As soon as we use religious beliefs as a foundation for how we shape our principles of a shared world, we open the door to conflicts over different made up concepts. It ends up being as ludicrous as if people start a knife fight over which console, Xbox or Playstation is the best. Emotional attachments to the concept that comforts.

To follow science more is about collectively agreeing that, what can be proven for all, we agree by. Not arbitrary or unsupported claims that can never coexist between people of different cultures and beliefs. A shared world, shared existence requires a shared primary world view. If that can be combined with individual religious beliefs, sure, but so far I've yet to be convinced that the people of this world are able to co-exist with such powerful forces of psychology pulling their very experience of reality in such different ways compared to others.

What 'comforting results' are you referring to? If the illusions of religion are put aside, then what constitutes a real solution to the predicaments of human existence, other than comfort and standard of living? — Wayfarer

"Comfort", as I've explained in this discussion is primarily about ways and strategies to handle the dread and terror of meaningless existence. And what constitutes a real solution beyond religion and the materialistic? That's the solution I try to explore and formulate. One thing that I've found hints at such solution is the question; why cannot nature and the universe, as it is, be enough? Why does there have to be some divine purpose and meaning for us, in order for us to feel comfortable in existence? While Camus gives as an answer on how to live in the absurd, I'm asking, why not the opposite? To be curious about nature and the universe as it is and embrace it for what it is. Many Native American traditions follow a simple idea of harmony with nature around them. Removing the spiritual and religious claims in their traditions still leaves a practice that embrace our bond to reality and nature for what it is. A dedication to the ebb and flow of the ecological bond we have to the environment around us.

I see no major attempts to formulate a way of living outside religious beliefs in such a sense, I only see desperation and quick fixes. People won't explore, they want answers fast. That's why the materialistic has easily replaced religion for many people today, and why some double down into their religion as we can see in radicalized movements, or why many accumulate into extreme groups like Maga followers and cults like Qanon. Even the "Xbox vs Playstation" brawls follow the same path and psychological pattern.

In a sense, you hit on an important distinction with Buddhism. The problem I have is that there are still many religious components in Buddhism that muddy the clarity of its practical use. But it is further away from the religious and dogmatic claims that religions with a God component has. Which is why I say that religious practices in themselves has importance for our lives, I just think that we can accept existence for what it is, no more fantastical than we can rationally speculate, no less profound than what it already is. And live with practices that produce a meaningful experience without any fantasy components included.

Which is reductionist, 'explaining away'. I have studied religion through anthropological, sociological and psychological perspectives in comparative religion, but it's not reducible to those categories, even if they provide very useful perspectives. — Wayfarer

But they paint a pretty rational explanation for the emergence of different religious beliefs and claims, and that makes it hard to view such emergence of religion in history as having divine intervention. People are too susceptible to self-manipulation into fast explanations of the unexplained and too prone to solidify such inventions into larger patterns of meaning, in forms like mythology. The less proven facts that exist to explain anything, the easier people invent myths that grow into accepted facts.

Point being that the emergence of religion, especially sharing traits between cultures, has so many explanations in psychology and human behavior that it's hard to ignore all that and instead conclude the emergence of religion to be something more magical than it seems to be. We can also see the emergence every time we find a cult that has formed today. The same driving forces, the same inventions out of desperation for answers, but before the long term formation of myths becoming religious "facts".

All due respect, I don't believe you have 'knowledge that counters it'. What you have is a firm conviction. — Wayfarer

In this I refer to when such knowledge exists. Like for instance, we have proven evolution to be true, we have proven general relativity. If someone makes a religious or other claim that acts in opposition to it, I won't act like there's some grey area to it, in those cases they are wrong, provable wrong. If there's a psychological explanation for a certain behavior, I cannot ignore that component when analyzing a concept. What my point was, is that religious claims considered "facts" by believers, but that has more rational explanations is not something I can ignore and just play along. When people start out their claims with a demand to accept something that has more provable or rational explanations than they provide, their entire argument falls apart and this is why I argue for a clear line drawn between religious belief, its fantasy/illusions, and the practices in religion that has clear provable value for our experience. To formulate a living beyond religious beliefs but retaining aspects that comfort against the dread. -

Wayfarer

26.1kOne thing that I've found hints at such solution is the question; why cannot nature and the universe, as it is, be enough? — Christoffer

Wayfarer

26.1kOne thing that I've found hints at such solution is the question; why cannot nature and the universe, as it is, be enough? — Christoffer

That's the philosophical question, and a deep question. I think the intuition is that at bottom, everything in nature is transient and perishable. I think at bottom there's a deep intuition that there is a flaw or fault or imperfection in nature and in human nature, for which the remedy is not to be found on the same level at which it is perceived. That is expressed in different mythological and metaphorical clothing in different cultures. In Buddhism for example, it is the observation that existence is dukkha, one of those hard-to-translate terms that is usually given as 'distressing' or 'unsatisfactory'. The root of this dukkha runs very deep, and is ultimately related to the inherent tendency of beings to cling to sense-objects as sources of a satisfaction that they can never provide, as they are by nature transient and perishable. Hence the valuing of renunciation and giving up attachments. The ultimate aim of Nirvāṇa or Nibbana is realising the state of deathlessness.

In the Christian mythos, the unsatisfactoriness of existences is put down to the Fall, which is signified by the 'fruit of the knowledge of Good and Evil'. I take that to be a symbolic representation of self-consciousness, the burden of our reflexive intelligence. Through faith in Christ, the believer overcomes the sense of separateness and anxiety and the fear of death, by the realisation of the individual union or oneness with the divine (although this is highly attenuated in popular religions many of which have become corrupted in my view).

we have proven evolution to be true, we have proven general relativity. — Christoffer

Of course. Inside the Catholic Church, there was dissent over Galileo's censure. Whilst the conservatives were keen to see him condemned, there were progressives who believed the entire effort was misconceived. The Church is concerned with 'how to go to Heaven, not how the Heavens go', was their mantra. They lost the argument (much to the discredit of the Church.) Likewise after the publication of the Origin of Species, whilst some conservatives were quick to anathematize it, there were many within the Church who saw no inherent conflict between evolution and divine creation. It wasn't until the American fundementalists came along that it really blew up. But for those who never believed the literal truth of creation myth, the fact that they are *not* literally true is not the devasting blow against religion that Richard Dawkins seems to think. Origen and Augustine used to ridicule the literal reading of Scripture in the 1st and 4th centuries AD respectively.

To formulate a living beyond religious beliefs but retaining aspects that comfort against the dread. — Christoffer

I think a genuine religious path charts a way altogether beyond dread, not that that is necessarily an easy path to tread. In philosophical terms, I put it this way: humans are not simply physical beings. They are metaphysical beings, whether they know it or not. Our culture has undermined or even demolished the customary framework within which that was articulated and understood, so we're now looking to science for moral guidance, which is a mistake, as science is only quantitative and objective. But the spiritual quest is ongoing, a current Pew study shows that 70% of Americans see themselves as spiritual in some way, even outside the confines of what is strictly called religion. -

Christoffer

2.5kThat's the philosophical question, and a deep question. I think the intuition is that at bottom, everything in nature is transient and perishable. I think at bottom there's a deep intuition that there is a flaw or fault or imperfection in nature and in human nature, for which the remedy is not to be found on the same level at which it is perceived. That is expressed in different mythological and metaphorical clothing in different cultures. In Buddhism for example, it is the observation that existence is dukkha, one of those hard-to-translate terms that is usually given as 'distressing' or 'unsatisfactory'. The root of this dukkha runs very deep, and is ultimately related to the inherent tendency of beings to cling to sense-objects as sources of a satisfaction that they can never provide, as they are by nature transient and perishable. Hence the valuing of renunciation and giving up attachments. The ultimate aim of Nirvāṇa or Nibbana is realising the state of deathlessness.

Christoffer

2.5kThat's the philosophical question, and a deep question. I think the intuition is that at bottom, everything in nature is transient and perishable. I think at bottom there's a deep intuition that there is a flaw or fault or imperfection in nature and in human nature, for which the remedy is not to be found on the same level at which it is perceived. That is expressed in different mythological and metaphorical clothing in different cultures. In Buddhism for example, it is the observation that existence is dukkha, one of those hard-to-translate terms that is usually given as 'distressing' or 'unsatisfactory'. The root of this dukkha runs very deep, and is ultimately related to the inherent tendency of beings to cling to sense-objects as sources of a satisfaction that they can never provide, as they are by nature transient and perishable. Hence the valuing of renunciation and giving up attachments. The ultimate aim of Nirvāṇa or Nibbana is realising the state of deathlessness.

In the Christian mythos, the unsatisfactoriness of existences is put down to the Fall, which is signified by the 'fruit of the knowledge of Good and Evil'. I take that to be a symbolic representation of self-consciousness, the burden of our reflexive intelligence. Through faith in Christ, the believer overcomes the sense of separateness and anxiety and the fear of death, by the realisation of the individual union or oneness with the divine (although this is highly attenuated in popular religions many of which have become corrupted in my view). — Wayfarer

And it is this that I speak of. The existential dread, this "Dukkha". However, in Buddhism, it seems that "Samudaya" describes the cause of "Dukkha" and that the cause of suffering is our craving for "things" and pleasures. But what I'm saying is that the cravings for things, for the materialistic needs, pleasures etc. isn't the cause, it is the symptom due to our desperate need for comfort against the dread. The dread is the curse of knowledge and the irony is that while our knowledge has produced better living conditions, it also opened our eyes to the meaningless, producing this existential dread. The more we know, the more clearly we see our existence.

In such line of thinking I'm aligning somewhat with Buddhism in that I argue for finding a harmony with the natural world and universe, a balance, that does not rely on materialistic or delusional comfort. Materialistic, in this concept, is how many live their life today; buying new things, craving for the next pleasure, the addictive behavior that never reaches a content state and blinds by the noise of the sum of all material. Or the delusional, to surrender to a made up concept, giving up the ability to conduct critical thinking and wisdom in favor of an authority to form a fixed worldview that controls you. The delusional is religion, how an authority, another, or even the self, create a fantasy concept that is then transformed into a factual description of reality, often complete and with a promise that this life and its suffering will end and be transformed into something better as long as you hold onto that belief and defend it, like a manufactured and raging obsessive–compulsive disorder.

Both are desperate and rapid responses to the dread, in order to try and keep it at bay. But I also see a creeping and increasing horror of uncertainty within those who live by these two strategies. How the dread still creeps into these people's lives. How the materialistic individual can sense the dead existence within their owned stuff. How they sometimes wake up and look upon all their things and see a dead manufactured ocean that slowly drowns them. Or that the religious person holds onto their faith, try to keep it solid and unchanging, consistent and unbroken but keep feeling doubt due to the world around them, from other perspectives giving them other answers, other stories that they cannot prove are more or less true than their own convictions, and their confusion rising into anger, horror and depression.

As we hear people in their dying breaths voice their regrets and memories, they most often talk neither about their materialistic journey or their religious beliefs, but about the people around them. About life as it was, no more, no less.

So truth for what truly gives us comfort seems not to be found in the materialistic, or religious belief or even the absence of it. But rather in the life we live, truly live, honestly, with ourselves and with others. Why then not accept reality as it is, no more, no less? Accept all knowledge as it is, as it grows, explore it as a constant journey, live in it without demanding more.

Such balance acknowledge the pleasures by not pushing them into their extremes. We can have things, as long as they support, not being the source of it. If we find meaning in music, we may value a good record player. But we do not constantly buy new record players to fill some void. We already filled the void with music and the record player is only a tool for that purpose and meaningful experience. In this sense, we aren't materialistic anymore because we do not handle things other than as tools for a purpose. And we do not need religious belief if we find harmony with the natural world as it is and we do not need to accept the religious teachings as facts to value the stories being told as teachings for a good life. And we do not need to believe in illusionary concepts to value the experience of meditation.

The flaw as I see it, is in this core belief:

I think at bottom there's a deep intuition that there is a flaw or fault or imperfection in nature and in human nature — Wayfarer

I don't think there are any flaws because there isn't a template of perfection anywhere to hold reality up against. Reality is what it is and everything about the human condition is rooted in how we interpret this reality through our emotional experience, not our intellect. People are experts in blaming the external world for their own shortcomings and sense of despair. If they aren't happy or content, they essentially blame the universe for it, calling it flawed. This is what I call the human arrogance. We place ourselves onto pedestals and try to judge the universe by viewing ourselves as masters of it or capable of mastering it without realizing that we're not only slaves to the universe and its laws, we are also part of it, equal to everything around us.

This arrogance of trying to fix the imaginary flaws of this reality is the driving force for the delusion of any solutions to those imaginary flaws. Such solutions, in the form of religious beliefs or comforts in the ownership of material only function as temporary comfort towards a dread that ironically only arise out of the initial arrogance in the first place.

The solution is to not have that arrogance in the first place, to not view reality and our existence as flawed. We do not explore this reality or control it because it needs fixing, we do it because we're part of it and our existence is already in balance with it. The comfort lies in finding this harmony with reality, not in trying to fix some imaginary flaw in it. We exist because the universe and reality is as it is, without reality having its principles and laws as they are, we would not exist at all. We therefore fool ourselves if we seek out to fix a flaw because the flaw is imaginary and changing reality would essentially annihilate us, including any ideal we try to achieve.

Of course. Inside the Catholic Church, there was dissent over Galileo's censure. Whilst the conservatives were keen to see him condemned, there were progressives who believed the entire effort was misconceived. The Church is concerned with 'how to go to Heaven, not how the Heavens go', was their mantra. They lost the argument (much to the discredit of the Church.) Likewise after the publication of the Origin of Species, whilst some conservatives were quick to anathematize it, there were many within the Church who saw no inherent conflict between evolution and divine creation. It wasn't until the American fundementalists came along that it really blew up. But for those who never believed the literal truth of creation myth, the fact that they are *not* literally true is not the devasting blow against religion that Richard Dawkins seems to think. Origen and Augustine used to ridicule the literal reading of Scripture in the 1st and 4th centuries AD respectively. — Wayfarer

All I see are shifting goal posts back and forth through history to fit a narrative that best suits the storyteller. And I question the need for any of these religious narratives and beliefs as they do not fix anything other than being good stories as inspiring fiction. There's a desperation boiling underneath it all as they seem to sense some core truth hidden under all that fiction but desperately hold on to their narrative in order to stay sane. It's why I call it "comfort" against the dread. Because removing the narrative and stare right into existence is downright terrifying, but necessary as a step before finding harmony and balance with reality as it is, without imaginary flaws to be fixed.

so we're now looking to science for moral guidance, which is a mistake, as science is only quantitative and objective. — Wayfarer

This isn't true however, it is a simplification of the experience of us who value science over beliefs. We do not seek moral guidance by it in the way you summarize it, and we do not ignore the human experience. We acknowledge the importance of human experiences, but we do not attribute magic to it because we don't have to, we accept our experiences for what they are. I think the core difference is that we do not view reality as "flawed", as you described it, and thus formulate any need to fix anything. We accept all things in nature and reality as they are, without attributing "good" or "bad" to them. Letting reality inform us how things are rather than us interpreting reality through human values and emotions.

As I see it, we are arrogant to believe ourselves to stand above reality, to believe that we have to fix some flaws of it because we cannot cope with reality as it is for us. Nothing about that means that science as a process is used to find meaning instead, only that it informs us not to be arrogant to value ourselves as more important in this reality.

Such a conclusion leads to something else than you frame us as, it leads to a balance with reality that I find much more in sync with reality than any religious belief can ever produce. A clear and direct indication of what we need to do in order to find true peace with our existence. And it shows that we cannot find it in the materialistic addiction, religious fantasy, the rejection of all or total control of our emotions, but instead in the acceptance of reality as it is and living in harmony with that realization as a state of mind.

Finding that state of mind and harmony defeats the existential dread without being dishonest with the truth of existence. It does not require lies, delusions, illusions or fantasy to produce a shield and spear to control the dread, rather, it lay down arms and let the dread flow past you through the acceptance of reality for what it is. -

Wayfarer

26.1kthe religious person holds onto their faith, try to keep it solid and unchanging, consistent and unbroken but keep feeling doubt due to the world around them, from other perspectives giving them other answers, other stories that they cannot prove are more or less true than their own convictions, and their confusion rising into anger, horror and depression. — Christoffer

Wayfarer

26.1kthe religious person holds onto their faith, try to keep it solid and unchanging, consistent and unbroken but keep feeling doubt due to the world around them, from other perspectives giving them other answers, other stories that they cannot prove are more or less true than their own convictions, and their confusion rising into anger, horror and depression. — Christoffer

As I said in the post you're responding to

I think a genuine religious path charts a way altogether beyond dread, not that that is necessarily an easy path to tread — Wayfarer

But plainly we're not going to agree on that.

Thanks for your considered and thoughtful responses. -

Mark Nyquist

783

Mark Nyquist

783

Wayfarer, I actually agree with you on your criticism of reductionism, not sure if you picked up on that. I'm a materialist, but there is a special case here. Mind can drive matter... no doubt. -

Wayfarer

26.1kI do notice that you’re working through all these ideas here. Which is just what this forum is for. :ok:

Wayfarer

26.1kI do notice that you’re working through all these ideas here. Which is just what this forum is for. :ok: -

Christoffer

2.5kAs I said in the post you're responding to

Christoffer

2.5kAs I said in the post you're responding to

I think a genuine religious path charts a way altogether beyond dread, not that that is necessarily an easy path to tread

— Wayfarer

But plainly we're not going to agree on that. — Wayfarer

It may be, in times when people lived inside such a bubble and never ventured outside. But how do you apply it in times like these, when the bombardment of alternative perspectives constantly question the validity of ones faith? Does treading that path soon not become impossible as any shred of doubt only creates its own type of dread, slowly intensifying and corrupting the ability to hold onto the specific faith. Would it not rather be better to explore a path that consist of better validation for its existence, finding a harmony that is more stable than the chaotic ocean of different religious beliefs clashing themselves to pieces and impossible to be convinced about in a socially complex society?

What I see today is this basically appearing in two types. Either a life of religious belief filled with doubt, keeping it hidden from others in order to try and keep it from being exposed to criticism, hidden crosses, hidden shrines, never talking to others about personal faith. Or turning to fundamentalism, shutting out all influences from the surroundings, extremify the bubble, silence anyone or socially excluding anyone who risk installing any kind of doubt, and double down on dogmatic dedication, isolating themselves from the rest of society or join societies in which this fundamentalism is the standard.

How can that hard path not become impossible when the world is constantly infusing doubt on a scale and movement that has never been experienced among religious groups before?

In another perspective, what is the goal for the believer with their belief? What are they striving for? Hoping for? If fundamentalism is the only path to successfully be convinced of where the path leads, what hope is there for non-fundamentalists to be free from this other type of dread setting in? The dread of possibly being wrong?

Wayfarer, I actually agree with you on your criticism of reductionism, not sure if you picked up on that. I'm a materialist, but there is a special case here. Mind can drive matter... no doubt. — Mark Nyquist

Can mind drive matter or are we simply another type of matter driving matter in perfect accordance with entropic processes? On a large enough scale, does not the complexity of the entire human race only just become another set of a system based on universal principles forming complex outcomes?

The problem with reductionism is that it focuses too much on trying to explain something complex by analyzing the details separately or trying to find a set pattern in a holistic overview of the sum of all parts. This is why I argue for emergentism since we see it all over in nature and in physics. For instance, you cannot explain consciousness with reductionism, it has been tried to death in scientific research. But emergentism instead acknowledge how the pieces of our brain and body cannot in of themselves form consciousness, rather it forms a new function not found in the parts out of the complexity that appears through the almost mathematically infinite sum of all parts, it emerges out of the complexity, it isn't directly the complexity itself. Which means it's not a tangible object that can be found somewhere, it is the result of all without clear and direct paths able to be seen between the result (consciousness) and its sources (parts).

This means that emergentism and materialism works better together than pure reductionism, and it solves much of the problems with how reductionism is unable to explain things like consciousness. I would however say that physicalism is a better modern term for how most materialists argue as materialism only traditionally focuses on matter, not physics as a whole. -

mcdoodle

1.1kCan mind drive matter or are we simply another type of matter driving matter in perfect accordance with entropic processes? On a large enough scale, does not the complexity of the entire human race only just become another set of a system based on universal principles forming complex outcomes? — Christoffer

mcdoodle

1.1kCan mind drive matter or are we simply another type of matter driving matter in perfect accordance with entropic processes? On a large enough scale, does not the complexity of the entire human race only just become another set of a system based on universal principles forming complex outcomes? — Christoffer

I'm an atheist but more sympathetic to religion than you. I don't quite know why.

From a historical perspective, to me the contrast between religion and science is overdone. Religious stories once claimed an over-arching importance, including a dominion over natural enquiry. But with the emergence (sic) of natural philosophy, it still remained and remains possible to be a good scientist and a religious believer, or so it seems to me. Many sects hang on to myths as if they were factually-based, so you have to choose your sect, and dissent sometimes from the mainstream, but science-as-metaphysics has its myths too. (Years ago a version of this forum had a poster who kept banging on about the difference between metaphysical naturalism and methodological naturalism, and the importance of this insight has stuck with me)

I've been studying philosophy academically in later life, and I confess, after lots more reading, that the notions of qualia and emergence feel dodgy. They come over like vague and sometimes slippery notions that are struggling to explain what happens beyond the limits of materially-based rational enquiry.

The thing is, they are attempting to do that because many people, including me, feel that something is missing, or not accounted for, in the elaborate networks of contemporary science. One way forward is to embrace other views as science: I think ecology makes that step. J J Gibson's ecological psychology, for instance, still has more potential to develop, once we see systems and potential systems in a wide view.

Ecology begins to imagine other creatures and indeed other non-creature elements in our world as agents. I don't know if you know 'Vibrant Matter' by Jane Bennett, which is an attempt to recover some out-of-fashion ideas about vitality in an ecological context. I read it full of optimism but finished it worried it was all a bit fuzzy-wuzzy, and I need to read it again.

And panpsychism.

And then there's the science of placebos, as an interesting example: placebos work. What's going on when they do and don't work? What is our analysis missing? Something in the very nature of our sociality, I'd say. -

Christoffer

2.5k'm an atheist but more sympathetic to religion than you. I don't quite know why. — mcdoodle

Christoffer

2.5k'm an atheist but more sympathetic to religion than you. I don't quite know why. — mcdoodle

It may look like that, but if you have the energy to read through my posts in this thread I think you will see that I'm sympathetic to religion in a certain way. I value the practices of religion but deny religious belief. What I mean by that is that there are too much evidence that show the positive effects of religious practice on the individual. The acts of praying, in a sense, meditation, the act of surrendering to a larger context, the act of feeling meaning.

One purpose of my exploration in philosophy is about finding such practice within a context that excludes religious belief. The reason being that religious belief skew and distorts an honest perspective of reality, especially collective reality. And so by that distortion the individual will always have trouble navigating reality as it truly is and will always end up in either internal or external conflict with others in a collective society. In order to find harmony, religious belief needs to be excluded. But in doing so we lose the parts of religion that is of tremendous importance to our mental health and social bonding. The practices we have in rituals, mythological storytelling and exploration needs to somehow be reworked into a context of non-religious belief, which requires a new paradigm of how to live life. We can see hints of this in how meditation has become a science backed practice for some, but the baggage of religious belief still haunts it and keeps inserting itself into groups conducting and leading others in meditation, and in doing so start to install beliefs in the supernatural once again.

So, I criticize religious belief, but I'm not unsympathetic in the way I think you see me.

I've been studying philosophy academically in later life, and I confess, after lots more reading, that the notions of qualia and emergence feel dodgy. They come over like vague and sometimes slippery notions that are struggling to explain what happens beyond the limits of materially-based rational enquiry. — mcdoodle

I'm not sure what you mean by them feeling dodgy? Qualia is the experience, the point of view experience of you, the individual. The experience you have right now reading this text is not something I can experience even reading the same text. It's the hard line between knowing about something (like how consciousness works) and the internal experience within that function and process. It relates to the concept of philosophical zombies, Mary in the black and white room, the Chinese room etc. and how it is seemingly impossible to cross that hard line and know that this emergent phenomena is in fact experiencing something with a point of view and not merely functioning as a simulation.

We can add another example of this in face blindness. As a person with face blindness tries to recognize a friend, the face-blind person will have developed strategies to recognize his friends without being able to see their face. His friends might not even know he is face blind as they, as outsiders from his mind, can only recognize that he functions just like they do when they meet, so they think that this face-blind person is functioning and experiencing reality just as they do, while he in fact only "simulates" recognizing their faces.

It's the major problem of AI research as well. When we have an AGI superintelligence that seemingly mimic or surpass human intelligence and we interact with it, how do we know that it has qualia? Or isn't just a form of functions that never has any holistic experience as a result? The problem with qualia is that we might never be able to know this, it's part of the hard problem of consciousness.

When it comes to emergent properties, it's actually very supported in science. It's everywhere in nature. Rudimentary functions in extreme numbers can form patterns generating a higher complexity and emerging functions that has no relation to the functions themselves. Just a basic example of this is how neutrons and protons in of themselves cannot be "wood", and the basic composition of a carbon molecule has a higher complexity than just the neutron and protons, but still does not produce "wood". Only when you combine a number of different compositions of atoms into a molecular structure do you get "wood" as matter, but that doesn't create the structure of "wood", which requires bonds of those molecules. And these bonds in relation to the environment (other bonds and other molecules) can produce the structure of a "tree". But that structure cannot be simply explained reductionistic by looking at neutrons and protons. The "tree" is an emergent structure and form out of the extreme complexity of the whole of its parts. The function a tree has in relation to the rest of the universe is a function that emerges out of all of it.

To draw connections to consciousness, it's all there. En emergent function that cannot be explained by its parts. If it sounds abstract it's because it is, because it's not tangible in the same way as an object. We can view it in the same way as how we have trouble viewing light as both a particle and a wave. We know there's this thing called consciousness, but it's also no thing but a function/process that exists beyond what we can seemingly measure. But if we apply emergentism to this it makes sense, a function that can only exist as a byproduct of a certain complexity that rises out of a specific set condition of less complex functions.

Some people who have gone through near death experiences have explained their experience waking up from it. As parts of the brain and body starts working again, but not fully in sync as a whole, they have explained a deep sense of confusion, hearing words, but not able to understand them, seeing light and images without having spatial knowledge etc. If consciousness is an emergent phenomena, then at less than full complexity the experience they talk about would logically form a broken sense of reality, even if some parts of the brain function correctly. They explained that reality started "popping" into clarity, in my interpretation, almost like if watching a Picasso painting start to pop its cubist sharp forms into realistic shapes until it feels familiar and correct.

As I see it, the emergent explanation for consciousness holds most promise out of all research on the topic. It may sound abstract, but it has an elegant logic to it. -

mcdoodle

1.1kI'm not sure what you mean by them feeling dodgy? — Christoffer

mcdoodle

1.1kI'm not sure what you mean by them feeling dodgy? — Christoffer

I'm sorry, 'dodgy' is too vague a word for my problems with qualia and emergence. I mean, both terms seem to me to cover too many, likely disparate, phenomena. In covering them they do give us indications of where thinking might go, but I doubt that any one idea is that comprehensive. That is, I accept the needs for explanatory terms which qualia and emergence are trying to fulfil, but they seem too all-embracing and thinly-justified.

Broadly I'm a pluralist. I think the search for the unity of science is a fool's errand, and these terms are, to simplify, trying to occupy spaces where the unity can't hold, or science lacks plausible claims (as it does for instance in much of social life). I like Nancy Cartwright's view of the philosophy of science, derived from years of working with and observing scientists: that scientific findings are often quite narrow, confined to very specific controlled circumstances, and that we vastly over-extrapolate from them.

...religious belief skew and distorts an honest perspective of reality, especially collective reality. And so by that distortion the individual will always have trouble navigating reality as it truly is and will always end up in either internal or external conflict with others in a collective society. In order to find harmony, religious belief needs to be excluded. — Christoffer

To me this demonstrates an excess of respect for a science-derived view of 'reality' and a deficit of respect for religion. To say to the religious, I respect much of what you achieve but your beliefs are bollox: how is that dialogue going to work? What's the word 'honest' doing in there? Do you think all those neuroscientific researchers whose work turns out to be unreplicable were 'honest'? Do you think people who dedicate themselves to a religious life are 'dishonest'? Where, more generally, do the ideas of 'harmony' and the 'collective' derive from, and why can't there be equal dialogue about them between the religious and irreligious? -

javra

3.2kIn order to find harmony, religious belief needs to be excluded. But in doing so we lose the parts of religion that is of tremendous importance to our mental health and social bonding. The practices we have in rituals, mythological storytelling and exploration needs to somehow be reworked into a context of non-religious belief, which requires a new paradigm of how to live life. — Christoffer

javra

3.2kIn order to find harmony, religious belief needs to be excluded. But in doing so we lose the parts of religion that is of tremendous importance to our mental health and social bonding. The practices we have in rituals, mythological storytelling and exploration needs to somehow be reworked into a context of non-religious belief, which requires a new paradigm of how to live life. — Christoffer

as well as:

Where, more generally, do the ideas of 'harmony' and the 'collective' derive from, and why can't there be equal dialogue about them between the religious and irreligious? — mcdoodle

Apropos the interplay between religious and irreligious beliefs and praxis: Back in my early twenties when I basically was an atheist in all implied senses of the word (no gods, no spirituality, etc.) a friend once asked me: “If you don’t believe in anything spiritually sacred, then why not choose to piss on a gravesite rather than, say, near an adjacent tree when you’re in a cemetery and there is no one else around?”

It’s a male-centric question, I grant, but, its non-gratuitous vulgarity aside, I still find it to be a good question in regards to beliefs and praxis.

I had my psychological answers back then—basically affirming that respecting the spiritual beliefs of others grants me psychological warrant to then expect that my own atheistic beliefs be respected by them in turn. Other people’s potential answer to the question might well be different. But I think the question can go fairly deep in terms of distinguishing the sacred (to each spiritual person and group of such their own) from the profane; as well as in addressing how the atheist relates to this sacred/profane distinction made by theists.

Not much of an argument for anything. So there’s no real need to address this post. But I’m mentioning this viewing it to directly address the connection between spiritual beliefs and praxis—be the praxis on the part of the theist or the atheist. (Here presuming most atheists to have respect for the gravesites of the dead, despite not interpreting the gravesite as anything spiritually sacred.) -

FreeEmotion

774Of course. Inside the Catholic Church, there was dissent over Galileo's censure. Whilst the conservatives were keen to see him condemned, there were progressives who believed the entire effort was misconceived. The Church is concerned with 'how to go to Heaven, not how the Heavens go', was their mantra. They lost the argument (much to the discredit of the Church.) Likewise after the publication of the Origin of Species, whilst some conservatives were quick to anathematize it, there were many within the Church who saw no inherent conflict between evolution and divine creation. It wasn't until the American fundementalists came along that it really blew up. But for those who never believed the literal truth of creation myth, the fact that they are *not* literally true is not the devasting blow against religion that Richard Dawkins seems to think. Origen and Augustine used to ridicule the literal reading of Scripture in the 1st and 4th centuries AD respectively. — Wayfarer

FreeEmotion

774Of course. Inside the Catholic Church, there was dissent over Galileo's censure. Whilst the conservatives were keen to see him condemned, there were progressives who believed the entire effort was misconceived. The Church is concerned with 'how to go to Heaven, not how the Heavens go', was their mantra. They lost the argument (much to the discredit of the Church.) Likewise after the publication of the Origin of Species, whilst some conservatives were quick to anathematize it, there were many within the Church who saw no inherent conflict between evolution and divine creation. It wasn't until the American fundementalists came along that it really blew up. But for those who never believed the literal truth of creation myth, the fact that they are *not* literally true is not the devasting blow against religion that Richard Dawkins seems to think. Origen and Augustine used to ridicule the literal reading of Scripture in the 1st and 4th centuries AD respectively. — Wayfarer

The above paragraph really highlights the issues that I am concerned with discussing.

Galileo's theory contradicted the church's teaching of the day. Since then, the church has abandoned that interpretation, and aside from the issue of the inerrancy of the Bible, that interpretation was not really in conflict with core doctrines.

The Origin of Species was different, in that it struck at the heart of many themes or even doctrines in the Bible, the creation of human beings out of dust, without any hominid ancestors of any sort. Even today, the theology of human origins is something the cannot accept.

Of course some will see no conflict between evolution and divine creation, but some will do. What is so difficult for me to accept is the pure logical contradiction between the act of divine creation and and all natural creation. Beliefs aside, the practice of reason absolutely demands that such a contradiction be recognized, what you want to do with that later is another matter.

It was not the fundamentalists: people from antiquity have always believed in divine creation, there was no evolution to believe in, there were other theories, Greek theories, perhaps, and they were aware of them. The Hindu beliefs, for example* are different. Where is the recognition that the beliefs of those who hold to Creationism are equally valid, or even the condemnation of these beliefs as being erroneous?

In any case the fundamentalists ran into trouble when they tried to influence what was taught in schools, private beliefs would have not been a problem. As usual, legislating a particular type of morality will be met with opposition. This seems to be all about textbooks.

But for those who never believed the literal truth of creation myth, the fact that they are *not* literally true is not the devasting blow against religion that Richard Dawkins seems to think — Wayfarer

For those who have always believed in creationism, and not necessarily the creationism myth, the theory of evolution is a devastating blow against their beliefs. That should be recognized.

*

Creation stories in Hinduism

What accounts of the origins of the universe are found in Hinduism?

In Hinduism the universe is millions of years old. In line with the Hindu belief in

reincarnation

, the universe we live in is not the first or indeed the last universe.

For Hindus the universe was created by Brahma, the creator who made the universe out of himself. -

Wayfarer

26.1kOf course some will see no conflict between evolution and divine creation, but some will do. What is so difficult for me to accept is the pure logical contradiction between the act of divine creation and and all natural creation. Beliefs aside, the practice of reason absolutely demands that such a contradiction be recognized, what you want to do with that later is another matter. — FreeEmotion

Wayfarer

26.1kOf course some will see no conflict between evolution and divine creation, but some will do. What is so difficult for me to accept is the pure logical contradiction between the act of divine creation and and all natural creation. Beliefs aside, the practice of reason absolutely demands that such a contradiction be recognized, what you want to do with that later is another matter. — FreeEmotion

Excellent question, but I don't think there has to be a 'pure logical contradiction' between creation natural and divine. I think it's pretty unsure what divine creation really means. It's a question of interpretation. All spiritual faiths have inner and outer meanings - you might ask why they must be expressed in symbols and parables, but the reason is, they convey truths that are very difficult to grasp, using imagery and allegories from everyday life. Misunderstanding those symbolic truths has been criticized even within the Christian faith from very early days. I've often re-quoted the following passage, although I'll acknowledge that I haven't read the book it came from:

Usually, even a non-Christian knows something about the earth, the heavens, and the other elements of the world, about the motion and orbit of the stars and even their size and relative positions, about the predictable eclipses of the sun and moon, the cycles of the years and the seasons, about the kinds of animals, shrubs, stones, and so forth, and this knowledge he holds to as being certain from reason and experience.

Now, it is a disgraceful and dangerous thing for an infidel to hear a Christian, presumably giving the meaning of Holy Scripture, talking nonsense on these topics; and we should take all means to prevent such an embarrassing situation, in which people show up vast ignorance in a Christian and laugh it to scorn. The shame is not so much that an ignorant individual is derided, but that people outside the household of faith think our sacred writers held such opinions, and, to the great loss of those for whose salvation we toil, the writers of our Scripture are criticized and rejected as unlearned men. If they find a Christian mistaken in a field which they themselves know well and hear him maintaining his foolish opinions about our books, how are they going to believe those books in matters concerning the resurrection of the dead, the hope of eternal life, and the kingdom of heaven, when they think their pages are full of falsehoods on facts which they themselves have learnt from experience and the light of reason?

Reckless and incompetent expounders of Holy Scripture bring untold trouble and sorrow on their wiser brethren when they are caught in one of their mischievous false opinions and are taken to task by those who are not bound by the authority of our sacred books. For then, to defend their utterly foolish and obviously untrue statements, they will try to call upon Holy Scripture for proof and even recite from memory many passages which they think support their position, although they understand neither what they say nor the things about which they make assertion. — St Augustine, (quoting 1 Tim 1:7, from The Literal Meaning of Genesis).