-

Moliere

6.5kWhat about them? If I could look at the world through the eyes of a cat, I wouldn't expect to experience trichromatic vision. Just the same as I wouldn't through the eyes of a colour blind human. — apokrisis

Moliere

6.5kWhat about them? If I could look at the world through the eyes of a cat, I wouldn't expect to experience trichromatic vision. Just the same as I wouldn't through the eyes of a colour blind human. — apokrisis

They might look at the same wavelength energy in some sense, but we know that there is no counterfactual sensory judgement taking place, such that they see red and not green. And my argument is that experience is nothing but a concatenation of such base level acts of discrimination. Physical values have to be converted to symbolic values in which an antagonistic switching off a neural response is as telling as switching that response on. Now both 1 and 0 have meaning. Absence means as much as presence, whereas back in the real world, there is only the presence. — apokrisis

You are advocating Panpsychism it appears. For some reason the right wiring of a complex brain adds something different. The complexity of the patterns being woven lines up all the protoconsciousness to create not just bare mentality but mental content.

Yet that is still a mystical tale as the protoconsiousness remains itself rationally unexplained and beyond empirical demonstration. From a theory point of view, it is a hypothesis is not even wrong. — apokrisis

I'd say that any theory of consciousness, from that same point of view, is not even wrong. That's just where we're at. I wouldn't call this pan-psychism, though -- I'd call it (a form of) property-dualism, which seems to fit nicely in with mind-body dualism (considering that they are theories for two different questions). It would take both a third-person proto-conscious bit and a first-person proto-conscious bit to produce some qualia. (so, a rock, having no mind stuff -- let's just say -- wouldn't have qualia, nor would some dis-embodied mind, though it may be thinking of things or making computations).

I mention animals because they would, using your line of arguments against dualism, also count as counter-arguments because they will experience the world differently. What seems to me to be the case is that you believe a dualism couldn't explain deviation in experience, whereas what I'm saying is that a belief that experience is nothing but a concatenation of base level acts of discrimination couldn't explain constancy.

Here are some other things which dualism has to offer:

Explains...

the tendency towards animism.

The existence of relationships becoming de-mystified, including relationships not just with people but also with animals, plants, and objects.

How emotion flows out into the world, and vice-versa -- the inter-penetrable nature of the boundary between mind and world, and why it isn't a hard barrier.

How it is that society is characterizable as a mental phenomena, even when it isn't itself a mental phenomena.

How it is we are able to perceive the minds of others.

De-mystifies the existence of mind in the first place.

And, as I've already mentioned, dualism explains why it is that experience has so many striking regularities.

Were this a research program these would be at the end of my poster board as further areas that need research ;).

But it shouldn't be any surprise that dualism, having fallen out of favor, needs an update. That's what happens to transcendental frames as they are dropped -- they fall out of date, and the new frame is what gets updated with the new information. I just don't think that experiential deviation is enough of a reason to reject it (and, also, I'd include animals, unlike the Cartesian variety of dualism). It seems to me that, just as the strawberries here are being counted as evidence for the brain editing or adding colors, that deviations of this sort would just be examples meant to elucidate the particulars of the mind. i.e. 'needs further research' :D

I certainly agree that the self-conscious human mind is socially contructed. The ability to introspect in an egocentric way, rationalise in an explictly logical fashion, reconstruct an autobiographical past, etc, are language-based skills that we learn because they are expected of us by the cultures we get born into.

So that is part of the semiotic story. Adding a new level of code - words on top of the neurons and genes - allows for a whole new level of developmental complexity.

Qualia are perceptual qualities and so are a biological level of symbolisation. Even a chimp will experience red due to a similarity of the circuits. But only humans have the culture and language that makes it routine to be able to introspect and note the redness of redness. We can treat our brain responses as a running display which we then take a detached view of. Culture teaches us to see ourselves as selves...having ideas and impressions.

So the point then about the red strawberries is that there is also still the actual biological response that can't be changed just by talking about it differently. And this shows that the biological brain itself is already a kind of rationalising filter. We never see the physical energies of the world in any direct sense. The world has been transformed into some yes/no set of perceptual judgements from the outset. It is already a play of signs. And so the feeling of what it is like to be seeing red is somehow just as much a sign relatiion as the word "red" we might use to talk about it with other people.

If you are a physicalist, you want to somehow make redness a mental substance - a psychic ink. And if we are talking about colour speech, we are quite happy that this is simply a referential way of coordinating social activity or group understanding. The leap is to see perceptual level experience as also sign activity - a concatenation of judgements - not some faux material stuff. — apokrisis

Something I'm not quite following here is how you escape the charge of representationalism. Or perhaps this is just something I thought you were trying to say, but aren't? If red is a sign, then it does seem that the mind is representational at least. (at least, as I understand sign -- a signifier and a signified, a mark and a mental-thing-ish-semantic-bit fused together)

Just asking for clarification here.

The mind is a modelling relation with the world. And after all, it should feel like something to be in that kind of intimate functional relation, right?

I don't think so, per se. At least, if we are physicalists. If not, then it seems that red could serve just as well as blue, as the inverted-spectrum argument goes -- and, in fact, if it's just a large functional organic-machine, that wavelengths are just as good as red-ness because that's still information, a pre-sign informational bit which can be converted into an electrical-voltage-sign which enters the dynamic system known as the brain, which sends out its signals to the body to reproduce.

But one need not feel anything in this process for reproduction to occur. All that would be needed is for information to be fed into the functions which generate signals which form the basis of signs. -

Robert Lockhart

170Sapientia: I would say that the general point to recognise concerning such discrepancies of personal experience among individuals regarding their interpretation of sensorialy perceived phenomena - typically as reported in this thread - is that such phenomena, by definition, do not exist objectively but in reality are merely the product of the interplay necessarily occurring between elements external to the observer and the internal neural processes by which interpretation is effected.

Robert Lockhart

170Sapientia: I would say that the general point to recognise concerning such discrepancies of personal experience among individuals regarding their interpretation of sensorialy perceived phenomena - typically as reported in this thread - is that such phenomena, by definition, do not exist objectively but in reality are merely the product of the interplay necessarily occurring between elements external to the observer and the internal neural processes by which interpretation is effected.

In that context then the question, “What is an objects’ ‘real’ colour” is surely a contradiction in terms in that only the wave lengths of the light emitted by an object can have an objective existence, 'its colour' being an attribute not of the object itself but a product of the observer's neural processes. It's merely the innate similarity of the neural processes by which perception is enabled existing among individuals that enables a pragmatically useful consistency of agreement between them regarding their interpretation of any given sensorialy perceived phenomena. -Alien beings for example could in principle be characterised by neural processes relevant to sensorial perception effectively inimical to our own – thus rendering mutually consistent interpretation impossible!

The point to recognise – not one of the more difficult concepts in philosophy perhaps - is that sensorial experience must necessarily be a product of the neural processes mediating between the observer and those elements external to him, the idea that such experience is objective being, understandably, just a popularly received illusion!

An objective description of the mechanisms of such mediation (I think personally btw) is likely more an excercise relevant to the methodology of science than the somewhat byzantine and recondite speculations of metaphysics - the sometimes apocryphal complexities tending to be introduced by the latter discipline into this problem being borne perhaps of its origin in an age ignorant of the concept of 'cause and effect', as this type of interaction to describe the relationships occurring between material phenomena came in subsequent ages to be gradually recognised cocurrent with the development of the scientific method itself as capable to adequately describe - ultimately in a comparatively simple and logically coherent manner - genres of phenomena such as this! -

apokrisis

7.8kSomething I'm not quite following here is how you escape the charge of representationalism. — Moliere

apokrisis

7.8kSomething I'm not quite following here is how you escape the charge of representationalism. — Moliere

I'm saying that the intent is not to re-present reality to the self - display sensory data so it can become the subject of experience. Instead the intent is to form a pragmatic modelling relarion with the world. So signs might mediate that, but the implied need for realism, completeness, faithfulness, etc, drops out.

In reality, the physical difference between green and red wavelengths is nothing more but a slight variation in wavelengths. But the mind sees two absolutely opposed things. Red and green can't mix as far as experience is concerned. So the mind is introducing a completely fake boundary into its view of the world. It is certainly not representing the continuous variation of the same thing - radiation - in constructing a model where a binary difference is what gets represented ... even when the physical display, as with the strawberries, doesn't emit any red.

And we can understand that from the way maps don't have to recreate territories. They just have to tell a tale of critical actions we would take at certain points in a history of motions. That is how they become a model - a model of our interaction with the world, not a model of the world as such, and so that is how a self arises. The self is the thing of the model representing some state of "selfish" intentionality in representing a set of critical actions.

So the mentality becomes the fact of a coordination between a body and a world. The sensory display is not a picture awaiting interpretation, it is the act of interpretation or mediation itself. -

Janus

18kI'm saying that the intent is not to re-present reality to the self - display sensory data so it can become the subject of experience. Instead the intent is to form a pragmatic modelling relarion with the world. So signs might mediate that, but the implied need for realism, completeness, faithfulness, etc, drops out. — apokrisis

Janus

18kI'm saying that the intent is not to re-present reality to the self - display sensory data so it can become the subject of experience. Instead the intent is to form a pragmatic modelling relarion with the world. So signs might mediate that, but the implied need for realism, completeness, faithfulness, etc, drops out. — apokrisis

So, the intent of your whole account is not to represent reality? Has the " implied need for realism, completeness, faithfulness. etc." "dropped out' of it? If your account is merely a pragmatic model, then what is its actual purpose? If it is to be justified by being purportedly more coherent than 'standard models', and not in terms of its purportedly corresponding to anything, then what if it is found by most thinkers to be less coherent, and thus less compelling than a standard dualistic account? How will its recommendation then be justified? -

apokrisis

7.8kSo, the intent of your whole account is not to represent reality? Has the " implied need for realism, completeness, faithfulness. etc." "dropped out' of it? — John

apokrisis

7.8kSo, the intent of your whole account is not to represent reality? Has the " implied need for realism, completeness, faithfulness. etc." "dropped out' of it? — John

That's a good point. I was talking about the biological level of neural modelling. And that is much more strictly pragmatic. Animals really are locked into a practical relationship with their environments.

Humans - though the development of words and numbers - have shifted to a far more abstract and philosophical relation with existence ... apparently.

But then the counter to that is check out what we mostly actually do and it is still pragmatic. We are simply learning to see our environment in a way that gives us greater technological control. We are imagining the world as a set of concealed sources of energy and material that can be redirected to fulfill our general (entropic) desires. So a colonial settler arrives in a new country and sees immediately forests that could be fields, hills that could be forts.

And yes, I would be quixotic perhaps in wanting to step back from all that practical activity to try to see its reality - stand outside of it to make sense of it ... knowing it is still just another exercise in mapping perhaps.

But there are reasons to think that it is not just a new level of arbitrary mapping. Reality is turning out to have mathematical or Platonic strength irreducibles. That is how I regard the metaphysics of Peircean semiosis. It captures the fundamental causal logic of existence. And so what begins as mere epistemology becomes the ontological hypothesis being empirically explored.

So semiosis starts as a model of human psychology. And it turns out (the reason I got involved) to be precisely how biology now understands the causal logic of living systems. Then the next step after that is to see that even the new science of dissipative structures (all that stuff that used to be classified as the new maths of fractals, chaos, complexity and self-organisation) is accounted for causally by the rational machinery of semiotics.

Thus semiosis is of course just another metaphysical map. But also it could prove to be the ultimate mapping in being the one that arrives at the mathematical limits of abstract conception.

Yet even if that is so, you could say that knowing this is itself not particularly pragmatic. How does it help to know why the Universe must exist in the form that it does? What use is that information to a biological creature really?

It is like why venture into outer space? You can't breathe there. Ultimately it is quite pointless - a distraction from your job of living a life down here on Earth.

But to get back to philosophy of mind, the semiotic perspective is instead a corrective in that it does bring you down to Earth in fact.

It says that the famous explanatory gap - why is "what it is like" actually what it is like, and not something else? - is a failure of proper pragmatism. It is a mistake to think that this is the kind of thing science should be able to explain. Explanations are there to serve purposes, and so can only deal with differences that make a difference - the actually counterfactual. In Wittgensteinian fashion, if red qualia could be inverted as blue qualia - and it would be impossible to stand at any viewpoint where the difference might show - then it is simply muddled conception to claim to be troubled by a difference that cannot make a difference.

So the thread illustrates that. All the talk about what colour a wavelength is really. All that matters to a modelling mind is the fact that wavelengths are discriminable in a way that has direct ecological validity.

So what should drop out of a science of the mind, or even a metaphysics of the mind, is this obsession with discovering what the "mind" really is. The fact that we even reify the process of being mindful as a noun - the mind - shows that already we are presuming a metaphysics of substantial objects. Instead, we should be in search of a process, and a process we can account for in the most metaphysically generic terms. My argument is that semiosis is turning out to be that generic model - a metaphysics of matter and sign rather than matter and mind. -

Janus

18k

Janus

18k

So what should drop out of a science of the mind, or even a metaphysics of the mind, is this obsession with discovering what the "mind" really is. — apokrisis

I agree with that, although I do wonder whether it makes any more sense to ask what matter or the sign "really is" than it does to ask what mind "really is". Also the notion of signs only seems to be intelligible in a context where mind/bodies that can read them and material mediums in which they are instantiated are assumed to exist.

For me intersubjective pragmatic concerns make sense when it comes to politics, economics, ecology, and science in general.

Pragmatic concerns are much more personal when it comes to religion, philosophy and the arts, though. What is it best to believe in those spheres? Whatever is most effective in terms of flourishing; whatever inspires in the creative or religious life, or whatever leads to a most ethical life, or loving attitude towards others. And since we are all unique individuals exactly what that optimum understanding or set of beliefs will be will vary from one person to the next. -

sime

1.2kHow is it possible to know if the illusion indicates a distortion of visual intuition as opposed to merely a linguistic mistake?

sime

1.2kHow is it possible to know if the illusion indicates a distortion of visual intuition as opposed to merely a linguistic mistake?

Perhaps all the illusion shows is that our ordinary language colour words don't have the meaning we thought they had. Certainly the strawberrys didn't look to have the normal tint of red we associate with them. I'm reminded of Wittgenstein's manometer. Is a mistake 'mere show' here? -

S

11.7kI think we're miscommunicating a bit here. To be fair, your argument was a google search. What I mean by 'drops out of the explanation' is that all that is said is we have reality on one side, and appearance on the other, and two claims about both. When asked how reality becomes appearance, the answer is 'the brain did it, just like it does with other objects to keep the color constant under different light conditions' where the main example was a blue sky.

S

11.7kI think we're miscommunicating a bit here. To be fair, your argument was a google search. What I mean by 'drops out of the explanation' is that all that is said is we have reality on one side, and appearance on the other, and two claims about both. When asked how reality becomes appearance, the answer is 'the brain did it, just like it does with other objects to keep the color constant under different light conditions' where the main example was a blue sky.

My question is -- what does the brain do to reality to make the appearance? But the answer is "it makes the appearance appear like the appearance appears, different from reality" -- which just masks the mechanism I'm asking after. — Moliere

And my question is: why do you ask, and why isn't that answer good enough for you? You could go and ask a neuroscientist who could probably give you a more detailed answer, although my guess is that you still wouldn't be satisfied. But why should I care? We only know what we know, and what we know enables us to answer the question in the way that I have done, which is good enough for the sake of this problem of perception, but perhaps not for some other problem that you seem to have introduced into the discussion. But this is a discussion about the former, and it need not digress into a discussion about the so-called hard problem to which you seem to be alluding.

I'm grouping these just as a side note, because it will take us pretty far astray.

A basic view of science:

Science is little more than a collection of arguments about certain topics. There are established procedures in place for certain sorts of questions, there are established beliefs due to said process, but in the end it's a collection of arguments about certain topics on what is true with respect to those topics.

At least, as I see it. We don't science it -- we make an argument. An argument, in this context, can of course include experimental evidence. But said evidence must, itself, be interpreted to make sense.

So really I'm just asking after the arguments in play. What does the scientist say to make his case convincing to yourself? What convinced you? — Moliere

I didn't elaborate because I didn't think it necessary. You already know about this, don't you? And even if you don't, others in this discussion have gone into detail on this. There is an established means of categorising colour based on range of wavelength. That's what I was referring to, and you can look it up yourself if need be. This is what I'm appealing to when I make the claim that the strawberries are not red, and I do so because I think that it makes for a better explanation than the alternative which claims that they are red. I don't really want to go into further detail than that, since I've already done so in previous comments, and I stand by those comments. I'd rather you just address what I've already said on the matter, rather than reiterate from the starting point of this discussion.

I mean that when Newton placed prisms to diffract light from the sun into a spectrum that the red part of the spectrum which came out of the prism was called 'red' not because it was had a larger wavelength and such was proven, but rather because the light was red. — Moliere

Okay, but that's not in itself a good reason to stick by that, is it? Times have changed, discoveries and developments have been made. And sticking by that doesn't resolve the problem of perception or explain optical illusions as well as you otherwise could. If you disagree, then you should explain how, and explain why you think that your explanation is better. I don't see how the better explanation can involve a picture which changes colour, because that just isn't how optical illusions work. Optical illusions are about naturally misleading perceptions, not magically changing realities.

No, that makes sense to me. — Moliere

Good. Well, that's analogous to my point, so if you concede to the one, you in effect concede to the other.

Though if all the parts are made of wood, and some parts are painted green while others are painted yellow, then it wouldn't make sense to say that the chair is green. :D — Moliere

Yes, I agree, but that is not analogous. Although if that was just a joke, then that doesn't matter.

In fact, what if the chair had a sticky reprint of the pixel-image we're discussing? Just to make it closer. Then, what color would the chair be? — Moliere

The colour of the pixels.

I'm thinking this is probably where we diverge the most, then. We seem to be in agreement on both the fallacy of composition and whether or not it has merit depends on the circumstances. If, in fact, the image is gray and appears red then certainly I am wrong.

So really it seems we're more in disagreement on determining which color is the real color, and which color is the apparent color. — Moliere

We're in disagreement about which colour is the apparent colour?! That's news to me. Obviously the apparent colour is whatever colour it appears to be, irrespective of the real colour. If it appears red in circumstance X, then red is the apparent colour in circumstance X, and if it appears grey in circumstance Y, then grey is the apparent colour in circumstance Y. Whence the disagreement?

As for disagreement about the real colour, it makes more sense to call real that which is mind-independent, hence that position being known as realism.

Cool. This is much closer to what I'm asking after.

I think this condition: " if we're talking about colour in terms of wavelength or some related scientific description,"

is likely the culprit of disagreement. Electromagnetic waves are real, as far as anything in science goes. But neither photons, nor atoms, have any color whatsoever. This is not an attribute of the individual parts of what we are saying causes the perception of color. Certain (regular, obviously, as you note about gray not being a regular wave) wavelengths of light correspond with our color-perceptions. But the color is not the electromagnetic radiation.

Color is -- to use your terminology -- subjective. I'd prefer to call it a first-person attribute not attributable to our physics of light, which is a third-person description of the phenomena of light rather than objective/subjective, myself. — Moliere

Photons and atoms don't need to have colour. If that's what we're talking about, then they're not red.

And the whole point with the picture of the strawberries is that the wavelengths of light do not in this case correspond to our colour-perception! Our colour-perception is red, but the wavelengths do not correspond!

It's not about waves, photons, atoms, radiation, or whatever, "having" colour, as such. It's about wavelengths of light according with an established colour categorisation, and it's about how useful this colour categorisation is. It is useful when trying to explain what happens with certain optical illusions, for example.

Colour is not subjective, unless by colour, you just mean colour-perception. But it was you yourself who introduced that latter term, so clearly the distinction is useful, yes?

I don't think we need to get caught up in the hard problem either. I wasn't really trying to go there, but it does seem related to the topic at hand. But it seems like we've managed to pair down our disagreement to one of "how to determine such and such", so there's no need to get into it. — Moliere

Okay.

Honestly, while brains are certainly a part of the picture of human consciousness -- I wouldn't dispute this -- we just don't know how we become conscious. Either there is no such thing in the first place, in which case there is nothing to explain, or if there is such a thing then we don't know how or why it's there. — Moliere

Maybe you're right. It does seem a bit of a mystery. I'm not agreeing or disagreeing with that. I think that that's a different problem that we needn't get into.

I think this is covered at this point. Let me know if you disagree. — Moliere

Yes, I disagree if you do. That is, I stand by my claim that optical illusions like the picture of the strawberries emphasise the fallibility of what we normally do, viz. jump to the conclusion that the strawberries are red because they appear red, and so if you disagree with that, then I disagree with your disagreement. -

S

11.7kSapientia: I would say that the general point to recognise concerning such discrepancies of personal experience among individuals regarding their interpretation of sensorially perceived phenomena - typically as reported in this thread - is that such phenomena, by definition, do not exist objectively but in reality are merely the product of the interplay necessarily occurring between elements external to the observer and the internal neural processes by which his interpretation is effected. — Robert Lockhart

S

11.7kSapientia: I would say that the general point to recognise concerning such discrepancies of personal experience among individuals regarding their interpretation of sensorially perceived phenomena - typically as reported in this thread - is that such phenomena, by definition, do not exist objectively but in reality are merely the product of the interplay necessarily occurring between elements external to the observer and the internal neural processes by which his interpretation is effected. — Robert Lockhart

I do recognise that. Who here doesn't? It's obvious, isn't it? Phenomena, by definition, as you note, are subjective.

In that context then the question, “What is an objects’ ‘real’ colour” is surely a contradiction in terms in that only the wave lengths of the light emitted by an object can have an objective existence, 'its colour' being an attribute not of the object itself but a product of the observer's neural processes. It's merely the innate similarity of the neural processes by which perception is enabled existing among individuals that enables a pragmatically useful consistency of agreement between them regarding their interpretation of any given sensorially perceived phenomena. -Alien beings for example could in principle be characterised by neural processes relevant to sensorial perception effectively inimical to our own – thus rendering mutually consistent interpretation impossible! — Robert Lockhart

Well no, not necessarily, since, in accordance with the established categorisation which has been around for quite some time, and is widely accepted in the scientific community, 'its colour' can be determined by the range of wavelength of the light emitted, rather than by appealing to some subjective quality or internal neural process. The wavelengths of light are objective, and that these wavelengths of light correspond to a particular colour category is objective. No need for the subjective there, and no contradiction in terms.

The point to recognise – not one of the more difficult concepts in philosophy perhaps - is that sensorial experience must necessarily be a product of the neural processes mediating between the observer and those elements external to him, the idea that such experience is objective being, understandably, just a popularly received illusion! — Robert Lockhart

Well, yes, I recognise that. Of course experience is subjective in the sense that it requires a subject. But why is this supposedly relevant?

An objective description of the mechanisms of such mediation (I think personally btw) is likely an excercise more relevant to the methodology of science than the byzantine speculations of metaphysics - the sometimes arcane complexities tending to be introduced into this problem by the latter discipline being borne perhaps of its origin in an age ignorant of the idea of 'cause and effect' type relationships, as these were envisaged by subsequent ages to occur between phenomena, and found capable of effectively describing, in ultimately a comparatively simple manner, types of phenomena such as this! — Robert Lockhart

I've argued that the scientific way of categorising colour in terms of range of wavelength of light is useful when dealing with the metaphysical problem of perception.

And, after all of this, you still haven't directly answered my questions, or at least explained why you haven't done so, which I think is bad manners. I think that it's quite important in philosophical discussions to stay on point, to be succinct, and to cut to the chase when need be. That's what I like to see. What I don't like to see so much is jargon, verbosity, tangent, or lack of clarity.

Please pay close attention to this next part, because I think that it's important. This is going to be my last attempt:

What colour are the strawberries? Just answer the question. Are they red? Do they just appear red? Are they grey? Do they in fact have no colour? All of the above? Some of the above? None of the above? Surely you have an answer, but even if not, you could just say that you don't know or that it depends, and if the latter, then briefly state what it depends upon. I find it annoying that you aren't coming back around to this point, when this is exactly where you should end up. If you're going to reply, I think that you should start with your conclusion(s) regarding the aforementioned, and then, only once you've done that, you may proceed with how you got there, and lastly anything else you think is of relevance. -

Moliere

6.5kAnd my question is: why do you ask, and why isn't that answer good enough for you? You could go and ask a neuroscientist who could probably give you a more detailed answer, although my guess is that you still wouldn't be satisfied. But why should I care? We only know what we know, and what we know enables us to answer the question in the way that I have done, which is good enough for the sake of this problem of perception, but perhaps not for some other problem that you seem to have introduced into the discussion. But this is a discussion about the former, and it need not digress into a discussion about the so-called hard problem to which you seem to be alluding. — Sapientia

Moliere

6.5kAnd my question is: why do you ask, and why isn't that answer good enough for you? You could go and ask a neuroscientist who could probably give you a more detailed answer, although my guess is that you still wouldn't be satisfied. But why should I care? We only know what we know, and what we know enables us to answer the question in the way that I have done, which is good enough for the sake of this problem of perception, but perhaps not for some other problem that you seem to have introduced into the discussion. But this is a discussion about the former, and it need not digress into a discussion about the so-called hard problem to which you seem to be alluding. — Sapientia

Well, the question was "What colour are the strawberries?" -- and your answer is that they are gray, in reality, but red, in appearance. My answer is that the strawberries are red, while the pixels are gray. Your answer seems to rely upon some kind of mechanism which the brain does, no? So, we can tell the strawberries are really gray because the brain does such and such. It seems a natural enough question to ask what it is that the brain does to make it appear as such and such when in reality it is this or that. Or, at the very least, how it is you determined this, and why we might want to determine things differently in this case than in other cases.

I'd think you would care for the answer because it would explain your belief here. I suppose you don't have to care though. You could certainly just believe it's true because a scientist says it's true.

If the explanation boils down to the brain does stuff here like elsewhere that's not exactly persuasive when we have a perfectly reliable method for determining color, I'd say. If we don't have a mechanism, then the explanation really does amount to about the same thing as magic. It's like all the neuro- talk you see in the papers everywhere meant to explain everything -- and the explanation boils down to the same: "The brain made you do it"

Here, at least, there's this notion of color constancy, so there's a bit more than this -- but not much.

I'd suggest that we could at least admit that we don't know the mechanism, but presume that the strawberries are really gray because the pixels are gray, and it seems like this brain-thing does stuff with perception so we believe that it might have something to do with it. At least, we could say that maybe someone with more knowledge than ourselves -- of which I am certainly not the most knowledgeable on the subject, I hardly even qualify as a hobbyist -- might know, but we ourselves don't understand the process, and so it would be unwise to claim we know in the first place.

But if that were the case, then I'd also suggest that it is quite reasonable to believe the strawberries are red, since we determine the color of images and things by looking at them -- and that it is the one who is claiming to know the real reality that should explain themselves in light of this.

I didn't elaborate because I didn't think it necessary. You already know about this, don't you? And even if you don't, others in this discussion have gone into detail on this. There is an established means of categorising colour based on range of wavelength. That's what I was referring to, and you can look it up yourself if need be. This is what I'm appealing to when I make the claim that the strawberries are not red, and I do so because I think that it makes for a better explanation than the alternative which claims that they are red. I don't really want to go into further detail than that, since I've already done so in previous comments, and I stand by those comments. I'd rather you just address what I've already said on the matter, rather than reiterate from the starting point of this discussion. — Sapientia

OK.

And the whole point with the picture of the strawberries is that the wavelengths of light do not in this case correspond to our colour-perception! Our Colour-perception is red, but the wavelengths do not correspond! — Sapientia

As far as I can tell no one here or elsewhere has actually verified this. We have extracted colors of pixels through a color picker, but no one has used a spectrometer or anything.

If we were able to shoot the light through a prism, I betcha we'd get some red.

It's not about waves, photons, atoms, radiation, or whatever, "having" colour, as such. It's about wavelengths of light according with an established colour categorisation, and it's about how useful this colour categorisation is. It is useful when trying to explain what happens with certain optical illusions, for example.

Colour is not subjective, unless by colour, you just mean colour-perception. But it was you yourself who introduced that latter term, so clearly the distinction is useful, yes?

Colour is colour-perception, yes. I think that's about right, though we have to be careful here -- there are obvious traps in saying it just in this way, and in using the term 'subjective'. Color is not subjective in several senses of the word 'subjective', either, I'd say. Hence why I'd prefer to avoid using the word 'subjective' -- first-person is better, I think.

Yes, I disagree if you do. That is, I stand by my claim that optical illusions like the picture of the strawberries emphasise the fallibility of what we normally do, viz. jump to the conclusion that the strawberries are red because they appear red, and so if you disagree with that, then I disagree with your disagreement. — SapientiaWe are, but that's the point. It emphasises the fallibility in what we normally do. — Sapientia

I just mean that I think we've found where our disagreement lies. You believe that this normal way of determining color is fallible in this case. This is what I'm contending is not the case -- that the method of using a color picker on the picture to determine the color of a pixel is not a good way for determining the color of the strawberries, that our looking at the image of the strawberries is adaquate for telling us the color of the strawberries in most cases, and that it is so in this case as well.

At the weakest I'm claiming that to continue in this belief without some kind of argument about the nature of color, the brain, and reality (in the case of this image) is rational.

So what I mean is that I believe we've honed down where our disagreement is. Not that we don't disagree. -

S

11.7kWell, the question was "What colour are the strawberries?" -- and your answer is that they are gray, in reality, but red, in appearance. My answer is that the strawberries are red, while the pixels are gray. — Moliere

S

11.7kWell, the question was "What colour are the strawberries?" -- and your answer is that they are gray, in reality, but red, in appearance. My answer is that the strawberries are red, while the pixels are gray. — Moliere

Your answer is false or misleading in this context. My answer doesn't have that problem. In this context, it is not misleading to say that the strawberries are not red, because we know I'm not talking about how they appear, or jumping to a conclusion about what colour they are based on how they appear, as we are likely to do in an ordinary context, where we don't think about things philosophically. But your answer doesn't work here, on a philosophy forum, where it's all about analysis, clarity and accuracy.

It also, in contrast to my answer, lacks plausibility when it comes to accounting for optical illusions - at least those relating to colour and perception in a similar way to that of the picture of the strawberries.

Your answer seems to rely upon some kind of mechanism which the brain does, no? So, we can tell the strawberries are really gray because the brain does such and such. — Moliere

That in combination with what I've said about colour categorisation. And so does yours, does it not? Don't you similarly think that we can tell that the strawberries are red because the brain does such-and-such?

It seems a natural enough question to ask what it is that the brain does to make it appear as such and such when in reality it is this or that. Or, at the very least, how it is you determined this, and why we might want to determine things differently in this case than in other cases. — Moliere

And a similarly worded question applies to you too, does it not? Why do you seem to think that this burden is on me, but not you? What would you be without your brain? What would you be capable of, if anything? Would you even be you? Would you be able to perceive colour or to determine anything at all without your brain? No, you wouldn't. So clearly your brain has an essential function here. So please explain to me in detail what your brain is doing in all of this, and I'll sit back and judge whether or not your answer is satisfactory. Does that seem fair to you?

Look, an explanation has already been given. If you can convince me why that explanation isn't good enough, then maybe I'll try to do better, or maybe I'll concede that I personally cannot do any better. I don't see why I should have to go into this in my own words, rather than just refer back to what has already been said or the related articles and scientific literature on this. Why do you want to know the ins and outs of the workings of the brain, anyway? What good will it do? It might well be interesting, but the conclusion won't change. You'd just have a more elaborate explanation.

I'd think you would care for the answer because it would explain your belief here. I suppose you don't have to care though. You could certainly just believe it's true because a scientist says it's true. — Moliere

I could believe it because I find it convincing and because a scientist says it's true, and the latter could be a valid appeal to authority. What I do know about this, I find convincing, and there are authorities who could do a better job than I can of explaining in detail what the process involves as well the various related implications.

If the explanation boils down to the brain does stuff here like elsewhere that's not exactly persuasive when we have a perfectly reliable method for determining color, I'd say. — Moliere

Ha! Perfectly reliable? You might have gotten away with that if it wasn't for those meddling scientists, who came along and discovered that colour is inextricably related to light emissions, and that particular ranges of wavelength in normal circumstances cause us to perceive particular colours - and were thus categorised accordingly - almost without exception. Then exceptions were discovered, and this is one of them. Hence the grey coloured strawberries appearing red, hence the unreliability of your method.

According to your method, it can't even be an optical illusion. It's just a picture of red strawberries. They appear red because they're really red. That's not very insightful, accurate or plausible, and lacks explanatory power with regard to the peculiarity of the grey, as opposed to red, pixels. That's just naive realism.

If we don't have a mechanism, then the explanation really does amount to about the same thing as magic. It's like all the neuro- talk you see in the papers everywhere meant to explain everything -- and the explanation boils down to the same: "The brain made you do it" — Moliere

We do have an explanation. The brain is the mechanism. One doesn't need to elucidate a mechanism within a mechanism within a mechanism ad infinitum or until you're satisfied, if that's even possible.

Here, at least, there's this notion of color constancy, so there's a bit more than this -- but not much. — Moliere

Yes, there's a start for you. Don't expect a lecture from me - I'm not a specialist on this subject. I'm not an authority. But it is possible for me to validly appeal to one if need be. But you shouldn't expect even such an expert to have all the answers. Our knowledge is limited. It would be misguided, I think, to keep pressing on and on like a child persistently asking "Why?", expecting an answer for everything when the answers already given are good enough for effectively dealing with many problems which might arise.

I'd suggest that we could at least admit that we don't know the mechanism, but presume that the strawberries are really gray because the pixels are gray, and it seems like this brain-thing does stuff with perception so we believe that it might have something to do with it. — Moliere

You and I might not know it, but that doesn't mean that it isn't known. But either way, that doesn't really matter, since we nevertheless have very good reason to believe that the brain has something to do with it. I'll settle for the above, especially if that means we can move on.

At least, we could say that maybe someone with more knowledge than ourselves -- of which I am certainly not the most knowledgeable on the subject, I hardly even qualify as a hobbyist -- might know, but we ourselves don't understand the process, and so it would be unwise to claim we know in the first place. — Moliere

So it's unwise to claim to know something in light of what the experts know, when we don't know it in the way that they do? I don't think that that's necessarily true. We have good reason to believe that the experts know what they're talking about, and it would be unreasonable to expect those of us who are not experts to expound upon these things to the extent of the experts.

But if that were the case, then I'd also suggest that it is quite reasonable to believe the strawberries are red, since we determine the color of images and things by looking at them -- and that it is the one who is claiming to know the real reality that should explain themselves in light of this. — Moliere

No, that's not quite reasonable, because an explanation has already been given, just apparently not to your satisfaction. The two are not one and the same. On the one hand, there's the explanation, and on the other hand, there's your satisfaction. Which one is unreasonable is arguable. Your lack of satisfaction does not of course mean that an explanation hasn't been given.

As far as I can tell no one here or elsewhere has actually verified this. We have extracted colors of pixels through a color picker, but no one has used a spectrometer or anything. — Moliere

No need. This has most likely been verified by scientists before we were even aware of it. The work has most likely already been done, and we can appeal to these authorities. Or we could harbour unreasonable doubt. Perhaps it's all just a joke or a conspiracy! Yeah, I don't think so. In this case, it is valid to appeal to authority and to make certain reasonable assumptions about what was done to verify the hypothesis.

If we were able to shoot the light through a prism, I betcha we'd get some red. — Moliere

Some red isn't red though, is it? We're talking about grey, which, as we know, contains some red. But if you conclude that it's red on that basis, you'd also have to conclude that it's yellow, and that it's blue, and so on. Which is just nonsense. It's grey.

Colour is colour-perception, yes. — Moliere

No.

I just mean that I think we've found where our disagreement lies. You believe that this normal way of determining color is fallible in this case. This is what I'm contending is not the case -- that the method of using a color picker on the picture to determine the color of a pixel is not a good way for determining the color of the strawberries, that our looking at the image of the strawberries is adaquate for telling us the color of the strawberries in most cases, and that it is so in this case as well. — Moliere

Okay. Contend all you like, but you're still wrong. X-)

At the weakest I'm claiming that to continue in this belief without some kind of argument about the nature of color, the brain, and reality (in the case of this image) is rational.

So what I mean is that I believe we've honed down where our disagreement is. Not that we don't disagree. — Moliere

There is some kind of argument as you describe above, so that's that box ticked. And you've focussed a lot on the brain - too much, perhaps - but don't forget about the established colour categorisation, and that whether or not something corresponds accordingly doesn't matter one iota about the brain. The brain has to do with why we perceive it a certain way, not why it is the colour that it is. -

Moliere

6.5kIt also, in contrast to my answer, lacks plausibility when it comes to accounting for optical illusions - at least those relating to colour and perception in a similar way to that of the picture of the strawberries. — Sapientia

Moliere

6.5kIt also, in contrast to my answer, lacks plausibility when it comes to accounting for optical illusions - at least those relating to colour and perception in a similar way to that of the picture of the strawberries. — Sapientia

This just begs the question, though. It is only an optical illusion if there is an illusion.

That in combination with what I've said about colour categorisation. And so does yours, does it not? Don't you similarly think that we can tell that the strawberries are red because the brain does such-and-such? — Sapientia

No, not at all in fact. All you need do is look at something to tell the color of something. That the brain is doing something to make the gray appear red seems to be the argument on the opposing side, by my lights.

Ha! Perfectly reliable? You might have gotten away with that if it wasn't for those meddling scientists, who came along and discovered that colour is inextricably related to light emissions, and that particular ranges of wavelength in normal circumstances cause us to perceive particular colours - and were thus categorised accordingly - almost without exception. Then exceptions were discovered, and this is one of them. Hence the grey coloured strawberries appearing red, hence the unreliability of your method. — Sapientia

Eh, scientists must make arguments like anyone else. I don't need to believe what a scientist has to say just because a scientist says it. There isn't such a thing as a valid appeal to authority in science. You can trust authority for certain purposes, and must do so very often in life, but that is no reason to believe something is true.

That's not how science works. You're perfectly rational to not believe something until you understand the demonstration -- you don't have to disbelieve it, either, per se. It doesn't have to be forbidden. But you certainly don't have to take a scientists word on anything.

That's, like, the whole point of science. It is open to anyone to interrogate and understand. It may take some time and effort to understand, and it's fair enough to say that you or I aren't up to snuff on a topic -- but that doesn't mean you have to believe anything. That's just anti-scientific thinking.

We do have an explanation. The brain is the mechanism — Sapientia

The brain is a black box. There are inputs and outputs being defined, but that's about it.

A chemical equation works in a similar manner.

H20 -> h2 + 1/2 o2

The "->" stands for "yields" -- while we may observe the beginning and ending products of a chemical reaction what is not demonstrated is the step-wise process which occurs. Many experiments are set up for the very purpose of determining the mechanisms of even singular chemical reactions. It is by no means an easy thing to determine, considering that you can't exactly observe the mechanism but, instead, have to infer it based on other measurements. (such as the rate of reaction, for instance).

So what I see when I hear "the brain does it" is "photons -> images" where "->" is "the brain does".

That is no mechanism.

One doesn't need to elucidate a mechanism within a mechanism within a mechanism ad infinitum or until you're satisfied, if that's even possible. — Sapientia

Why?

:D

So it's unwise to claim to know something in light of what the experts know, when we don't know it in the way that they do? — Sapientia

Yup.

At least if you're claiming the mantle of science. Scientific arguments are straightforward enough that given enough time they make sense. Claims of 'complexity' and 'difficulty' are just mystifications.

Evolution is probably my favorite scientific theory because it demonstrates this so very well. The arguments for evolution are easy to lay out and explain to someone. You have more advanced topics in biology, of course. But the overall theory of evolution? It is elegant and easy for most anyone of average intellect to grasp and understand.

No, that's not quite reasonable, because an explanation has already been given, just apparently not to your satisfaction. — Sapientia

"because", without qualification, is also an explanation. And it is the sort of thing one gives to stop questions, for certain.

But there's no reason to think that because this explanation has been given that one should be satisfied with it, or that it is reasonable either.

What counts as either a reasonable or satisfactory explanation, clearly, needs something more to it than simply that it has been given.

This is just to knock down the notion that because an explanation has been given that we must accept it as satisfactory or rational -- I don't think this is the explanation you are giving, just that it passes the criteria you're proposing here for the acceptance of an explanation as rational or satisfactory.

No need. This has most likely been verified by scientists before we were even aware of it. The work has most likely already been done, and we can appeal to these authorities. Or we could harbour unreasonable doubt. Perhaps it's all just a joke or a conspiracy! Yeah, I don't think so. In this case, it is valid to appeal to authority and to make certain reasonable assumptions about what was done to verify the hypothesis. — Sapientia

That's just bonkers. At the very least you cannot be claiming any kind of scientific value -- as you said earlier, 'to science' the problem -- if you aren't even willing to verify a belief with some kind of standard of measure, but just take it on faith that this was done. Even if the scientists have done this, it is on the basis of reproducibility that scientific argument is built.

You don't need to have faith in the priests of scientific knowledge that what they translate from the book of nature into the vernacular is the truth, may Darwin be praised. You just do the experiment yourself. You may do the experiment wrongly, of course, but so may they.

At least, insofar that we are defining color along the lines of wavelength, and not what it looks like, it does seem reasonable to ask -- what wavelength have you measured?

Some red isn't red though, is it? We're talking about grey, which, as we know, contains some red. But if you conclude that it's red on that basis, you'd also have to conclude that it's yellow, and that it's blue, and so on. Which is just nonsense. It's grey. — Sapientia

I conclude that it's red on the basis of what it looks like. This is my standard.

And you've focussed a lot on the brain - too much, perhaps - but don't forget about the established colour categorisation, and that whether or not something corresponds accordingly doesn't matter one iota about the brain. The brain has to do with why we perceive it a certain way, not why it is the colour that it is. — Sapientia

My focus on the brain is an extension of the argument for why the strawberries only appear red, when in reality they are gray. The brain, after all, is the causal agent proposed here.

As for what colour it is -- it seems to me that you're taking on faith that it is the color it is, since there hasn't been a measurement, no?

Or. . . maybe you're just using the standard I've proposed? Given what you have said about the lack of need to measure I'd say this is a fair inference.

You look at the pixel, it's gray, and therefore the strawberries are gray, because the strawberry image is made of the pixels, and color is the sort of property which translates from its bits to what it makes up, therefore the color of the strawberry image in reality is gray, though it appears red. Scientists explain the causal mechanism somewhere behind the scenes, but ultimately that's not what matters -- what matters is what color the pixels are.

But then you're just looking at the pixel to determine its color. Which is exactly what I've said we should do to determine something's color. It's just in the case of the strawberry, you believe the image stays gray because the pixels are gray. I'd say that without some kind of argument to the contrary, we should just determine color in the exact manner that we did the first time around -- by looking at it.

If we drop out the brain entirely, and we aren't measuring wavelengths -- and if we don't know what the brain is doing aside from vague hand-wavey references to 'color constancy', why should it be referenced at all except to say it does something somewhere? Which is hardly and explanation -- then the strawberry image is red, and the pixels are gray.

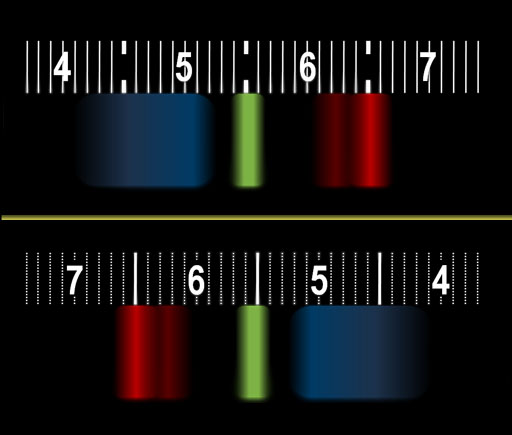

FWIW, I decided to hunt down some kind of image of monitors being measured by spectroscopes. The following websites abliges: http://www.chemistryland.com/CHM107Lab/Exp7/Spectroscope/Spectroscope.html

Assuming that their results are accurate:

This is what he got by aiming the spectroscope at the white portion of a screen. Not the image we're talking about, by all means, but this is what he gets.

What I don't see by looking at this is white -- I don't see how you get white from these results. I see how, knowing that when light combines such and such colors evenly you get white you can predict white. But I don't see how you get white from this. It seems to me that you must first know what white light looks like in order to know what colors you are going to get by combining this particular array of colors.

What would be of particular interest, I think, would be to see the spectroscopic results of one pixel compared to the entire photo. I don't think they'd be identical. I don't think anyone would think they'd be identical, either, for that matter. But if they're not identical, by your own theory of color, then the pixel and the image are not the same color, at least. Maybe you wouldn't go so far as to say they are red. You'd explain the difference in color by the differences in the gray palette of the picture, I'd say. That would save your theory.

But at the end of the day given that there are no such spectroscopic tests, I'd say that we really are just looking at such and such to determine such and such, and it is your belief that color is the sort of property which does not change as it aggregates into a whole which yields your belief that the strawberry image is gray, while it is my belief that we determine color by looking at it and there is nothing more to it than that which yields my belief that the strawberry image is red.

EDIT: 10 minutes after -- there's a very good image on that website which explores this difficulty more, too. The yellow one, when measured by the spectroscope, only comes out as a mixture of green and red -- it is not a 'pure' yellow, i.e. the yellow associated with the particular wavelength on the electromagnetic spectrum. Yet, clearly, the box is yellow.

Pointillism explores this notion quite well, too -- individual dots from a pen can be one color, but when you stand back, the picture is a mixture of the colors there. Impressionism does as well, and sort of pushes against the lay notion of color constancy presented in the pop articles so far -- that things do stay the same color as the light changes. But I'd have to know more about what is really be proposed to say for certain. -

sime

1.2k↪Moliere ↪Sapientia Doesn't the distinction between spectral colour and perceptual colour resolve your dispute? — jamalrob

sime

1.2k↪Moliere ↪Sapientia Doesn't the distinction between spectral colour and perceptual colour resolve your dispute? — jamalrob

I think they require an additional distinction between perceptual colour and verbally reported colour.

For although a subject's verbal behaviour might narrowly imply that they are percieving red strawberrys, the rest of their behaviour might indicate otherwise. The meaning of "red" after all, is a public definition and not in terms of private ostensive definition. -

Moliere

6.5kMaybe so. I could see it doing so, at least, just depending -- but I think the real dispute between Sapientia and I is more along the lines of what it means to know and also what it means to trust -- in particular, with respect to science.

Moliere

6.5kMaybe so. I could see it doing so, at least, just depending -- but I think the real dispute between Sapientia and I is more along the lines of what it means to know and also what it means to trust -- in particular, with respect to science.

I think what you propose would seperate our positions neatly. But I am uncertain that said distinction would actually address where the disagrement is occuring. Not that said disagreement has to be resolved here -- maybe that should occur in another discussion -- I'm just noting why I am uncertain.

We could adopt this distinction, but at the same time I sort of wonder if it would resolve our real dispute -- though, for sure, I'm not sure if we even have a real dispute or if we have hammered down where the best point of disagreement is at at this point.

Welcome to The Philosophy Forum!

Get involved in philosophical discussions about knowledge, truth, language, consciousness, science, politics, religion, logic and mathematics, art, history, and lots more. No ads, no clutter, and very little agreement — just fascinating conversations.

Categories

- Guest category

- Phil. Writing Challenge - June 2025

- The Lounge

- General Philosophy

- Metaphysics & Epistemology

- Philosophy of Mind

- Ethics

- Political Philosophy

- Philosophy of Art

- Logic & Philosophy of Mathematics

- Philosophy of Religion

- Philosophy of Science

- Philosophy of Language

- Interesting Stuff

- Politics and Current Affairs

- Humanities and Social Sciences

- Science and Technology

- Non-English Discussion

- German Discussion

- Spanish Discussion

- Learning Centre

- Resources

- Books and Papers

- Reading groups

- Questions

- Guest Speakers

- David Pearce

- Massimo Pigliucci

- Debates

- Debate Proposals

- Debate Discussion

- Feedback

- Article submissions

- About TPF

- Help

More Discussions

- Other sites we like

- Social media

- Terms of Service

- Sign In

- Created with PlushForums

- © 2026 The Philosophy Forum