-

The objectively best chocolate barsI'm not much of a chocolate eater these days, but I wouldn't turn down one of these if offered.

These were my favourite when I was very young:

-

TPF is moving: please register on the new forumI can't see those images though. "Content not viewable in your region" — Jamal

Yeah, Imgur decided to block the UK rather than comply with the Online Safety Act. -

Donald Trump (All Trump Conversations Here)Trump announces new 10% global tariff as he hits out at 'deeply disappointing' Supreme Court ruling

Dude just can't help himself. :roll: -

Donald Trump (All Trump Conversations Here)Trump's sweeping global tariffs struck down by US Supreme Court

The tariffs affected by Friday's ruling:

The country-wide tariffs Trump imposed on most of the world.

The ruling centres on Trump’s use of a 1977 law, the International Emergency Economic Powers Act (IEEPA), that gives the president the power to "regulate" trade in response to an emergency.

Trump first invoked it in February 2025 to tax goods from China, Mexico and Canada, saying drug trafficking from those countries constituted an emergency.

He deployed it again in April, ordering levies from 10% to 50% on goods from almost every country in the world. He said the US trade deficit – where the US imports more than it exports – posed an "extraordinary and unusual threat".

The unaffected tariffs

The industry-specific steel, aluminium, lumber and automotive tariffs, which were implemented under Section 232 of the Trade Expansion Act of 1962, citing national-security concerns.

Justices Brett Kavanaugh, Samuel Alito and Clarence Thomas dissented. -

Direct realism about perception

Alright, although I was hoping to take the move as a good point to end the discussion. It's gone on long enough for me. -

Direct realism about perception

On the monitor

The crux of my point was that these are non sequiturs:

A1. Our minds are "directed" towards X

A2. Therefore, we have direct perception of X

B1. Our cognitive operations are “answerable” to X

B2. Therefore, we have direct perception of X

This is shown to be so when X is “the world beyond the monitor”.

So direct perception must be explained in some terms other than A1 or B1.

On the science of perception

We're just going around in circles meaning different things by "direct perception". Given what naive and indirect realists mean by "direct perception", indirect realism is the scientific view of perception. As above, it’s not about A1 or B1. It’s about phenomenology and the ontological separation between experience (and its qualities) and distal objects (and their properties). That’s all it means for our experience of distal objects to be indirect.

On the structural "mirroring"

It's "accounted for" by the fact that distal objects and their properties are (usually) causally responsible for first-person phenomenal experience, and if the cause changes then the effect often changes. The colour I see is determined by the wavelength of the light (and my biology), so when the wavelength changes to a sufficient degree the colour I see changes. But differences in biology can entail that a greater degree of change in the wavelength is “hidden” because it does not affect a change in the colour seen, hence this colour being an epistemic intermediary. -

Direct realism about perceptionBut could they make true or false claims about the world beyond the monitors? Only if you grant that their cognitive operations are in some way answerable to how things actually are — and that answerability is precisely what I mean by the mind being directed toward mind-independent reality. If you deny that, you lose the normative dimension entirely. — Esse Quam Videri

This highlights the precise problem with your approach. Both of these are true in this scenario:

1. Their mind is "directed" towards the world beyond the monitors

2. They do not have direct perception of the world beyond the monitors

So even if our minds are "directed" towards a mind-independent world it does not follow that we have direct perception of it. The former is a red herring.

But causal mediation doesn't entail that what we are aware of in perception is a mental intermediary rather than the world itself. — Esse Quam Videri

It's not a case of either/or. We need to distinguish between direct awareness and indirect awareness. We can be indirectly aware of the world without being directly aware it.

So the question is; does our perceptual awareness of the world qualify as direct perception? Again, like with the monitor above, that our minds are "directed" towards the world does not entail that we have direct perception of it. More is required, and as I've argued before, this "more" concerns the constituents of first-person phenomenal experience. Modern science has firmly established that distal objects are not constituents of first-person phenomenal experience — hence the fall of naive realism — and so that we do not have direct perception of them.

By the mind "grasping" the structure of mind-independent reality, I mean something fairly precise: that in acts of understanding, we identify intelligible patterns (relations, unities, regularities, dependencies) that hold in reality itself, not just in our representations. — Esse Quam Videri

I haven't said that they only hold in our representations; I have only said that they do hold in our representations. A common argument you seem to make is that a) the direct objects of perception have structure, that b) mental phenomena can't have structure, and so that c) the direct objects of perception can't be mental phenomena. I reject (b); they can and they do.

So as you don't like to say that we have direct perception of qualia, I will instead say that we have direct perception of structured mental phenomena with (mind-dependent) qualitative properties and which erroneously seem to be distal objects — hence the allure of naive realism, and why our minds are "directed" towards a putative mind-independent world. And in the case that subjective idealism is false and we are not Boltzmann brains, this direct perception mediates indirect perception of appropriate distal causes (with structures which might "mirror" in some sense the structure of the mental phenomena — given their causal role — hence representational realism). -

TPF is moving: please register on the new forum

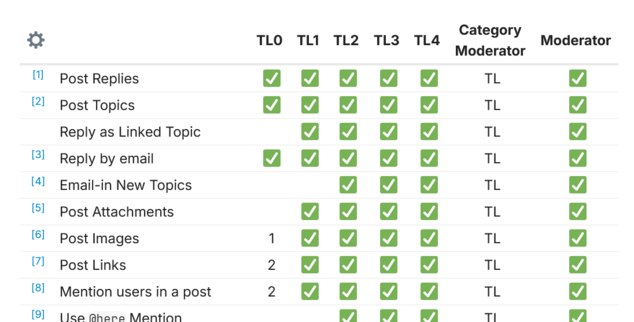

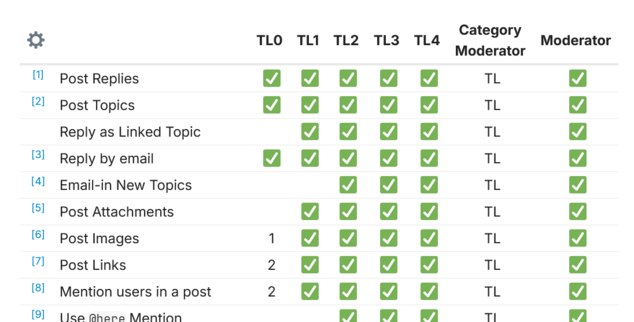

Weird, on https://dohost.us/index.php/2025/09/22/managing-users-trust-levels-and-permissions-in-discourse/ it says:

Can I customize the trust levels in Discourse?

Yes, you can customize the criteria for each trust level, although the default system is designed to work well out-of-the-box. Navigate to the admin settings to adjust the requirements for each level.

Edit: this is probably saying that you can change what a user must do to reach a trust level -

TPF is moving: please register on the new forum2. Discourse doesn't let me restrict uploads in any way apart from individual upload size. Like, only certain groups being able to upload images or a maximum number of uploads per person per month or whatever---these are not possible. — Jamal

You sure? Looks like it's editable via trust levels?

-

Direct realism about perception(1) How can the normativity and public assessability of perception be explained if all perceptual content is inherently private? — Esse Quam Videri

You and I seem quite capable of having a conversation and talking about world affairs, the colour of the dress, and headaches without ever having direct perception of the same things given that we've never met in person. The same would be true even if I was raised alone in a room by people on monitors, or if we all wore those visors. So rather than asking me to explain how this is possible, I think the burden is on you to explain why it wouldn't be.

(2) What explanatory work does the hypothesis that all perceptual content is “mental stuff” actually do that cannot be done otherwise? — Esse Quam Videri

The "explanatory work" is that it's entailed by our understanding of physics, physiology, neuroscience, and psychology, hence indirect realism being the scientific view of perception.

(3) What reason is there to think that the “structural” contents of perception (identity, unity, relationality, modality, etc.) cannot in principle be explained as the mind grasping the structure of mind-independent reality? — Esse Quam Videri

The mind "grasping" the structure of mind-independent reality is a really vague claim. What exactly do you mean by it? Does my mind "grasp" the fact that quarks are fundamental particles with color charge and spin? To an extent perhaps, but I'm no physicist. Regardless, none of us has direct perception of quarks.

And I'm not saying that we cannot in principle do whatever it is. I'm saying that whatever it is only in practice achieved indirectly. These same "structural" contents occur even if subjective idealism true, even if we're Boltzmann brains, even if we're dreaming, even if we're hallucinating, and even if light is slow and the apple was disintegrated five seconds ago. So these mind-independent objects are not necessary (except to whatever extent they're causally necessary). -

Direct realism about perceptionIf we assume subjective idealism then the apple is ultimately just "mind stuff", but this "mind stuff" isn't reducible to qualia. The phenomenology of perceiving an apple includes structured content -- unity, identity, difference, persistence, relationality, modality, temporality, blends of presence and absence, etc. -- that can't be cashed out in purely qualitative terms. — Esse Quam Videri

Then you're just splitting hairs over the meaning of the term "qualia". There's a reason I started the discussion by using the term "mental phenomena". It's a bit more inclusive.

If subjective idealism is true then we have direct perception of "mind stuff". The indirect realist claims that we also have direct perception of this "mind stuff" if subjective idealism is false. The introduction of mind-independent material objects as being causally responsible for this "mind stuff" doesn't make a difference — unless naive realism is true and these mind-independent material objects become constituents of first-person phenomenal experience. -

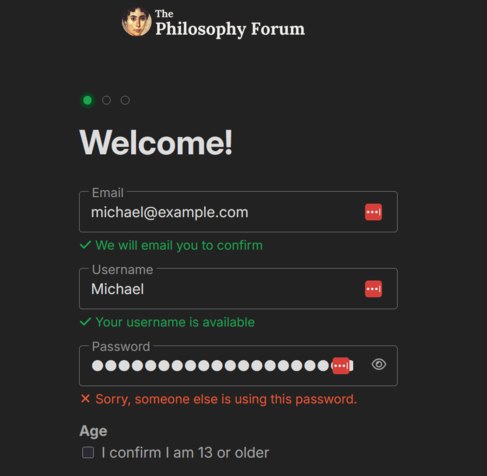

TPF is moving: please register on the new forumOut of pure impish curiosity on my part, why might one think it would? — Outlander

Because you might be stealing someone else's if you change it. Duh.

In my official capacity I would like to clarify that this is a joke and the picture is a clever deception. -

Direct realism about perception

Are you suggesting that we know through introspection that subjective idealism is false; that if subjective idealism were true then we wouldn't have the first-person phenomenal experiences (or intellects) that we have? I don't think that's correct. I think it's possible that John lives in a world that is introspectively indistinguishable from ours but in which subjective idealism is true, with phrases like "hearing voices", "seeing colours", and "feeling pain" describing the exact same first-personal phenomenal experiences that they describe in our world. I don't see why the existence of material brains or bodies or apples is necessary a priori.

Somewhat related are Boltzmann brains. Not only is it seemingly possible, but it's seemingly likely that during the lifetime of the universe there will be brain-like structures floating in the void of space experiencing exactly what you and I are experiencing and thinking exactly what you and I are thinking. It might seem implausible, and it might eventually be shown to be incompatible with physics, but it's not the sort of thing that can be refuted by the kinds of arguments you're making.

You might want to say that I only hear voices, see colours, and feel pain if subjective idealism is false and I am not a Boltzmann brain (else I only think I do, or is thinking also impossible?), but then we're clearly just talking past each other, because I see no problem in using such phrases to describe what does happen in these scenarios. -

Direct realism about perception

Most of what you say isn't exclusive to indirect realism. Direct realists who aren't eliminative materialists and who believe that we have headaches and direct visual perception of the Moon also believe in mental entities of some kind. They just disagree that these mental entities are the (only) direct objects of perception.

Your position on the matter is orthogonal to the traditional dispute, and is a position that even most direct realists will disagree with. -

Direct realism about perception

The synesthete sees colours when listening to music, the schizophrenic hears voices, and I feel a pain in my head the morning after drinking too much.

I can imagine John living in a subjective idealist world and having a first-person phenomenal experience that is introspectively indistinguishable from Jane's veridical perception in the real world. I don't see much sense in saying that John doesn't see or hear or feel anything. I think you're talking past the indirect realist if you define "John perceives something" in such a way that it's false if subjective idealism is true. -

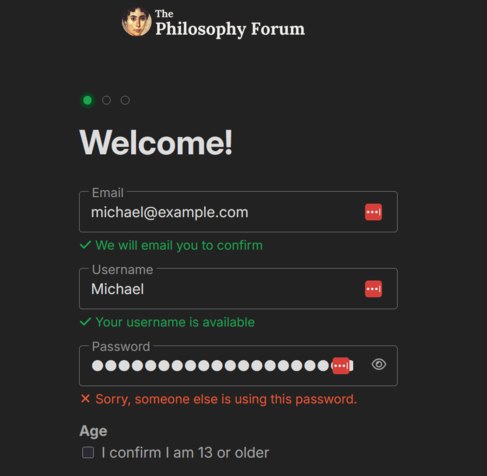

TPF is moving: please register on the new forumFor what it's worth on mobile you can click "Log in" at the top and then there's a "Sign up" link on the page.

Or rotate to landscape.

-

Direct realism about perceptionSo yes: I think godless subjective idealism can't sustain the normativity of perception.

...

Without God, premise (2) leaves perception without a proper object. — Esse Quam Videri

Okay, but it doesn't follow that these people don't see, hear, feel, taste, and smell things, or that the things they see, hear, feel, taste, and smell aren't qualia/sense-data/ideas/etc.

The introduction of material objects doesn't make the above sense of perception disappear. You've just introduced additional components to perception. So we have:

1. Perception of qualia

2. Normativity of perception

3. Perception with "proper" objects (whatever that means)

If subjective idealism is true then only (1) is true, but if subjective idealism is false then (1) is still true. Unless you want to argue that (1) is true if and only if material objects don't exist?

And I'd note that Berkeley's argument turns on an equivocation on "perceive." In (1), "perceive" means ordinary world-directed awareness. In (2), it means "have ideas." The conclusion only follows if both premises use the word in the same sense. My framework is, among other things, an insistence on not letting that equivocation pass. — Esse Quam Videri

Then we have:

(1) We perceive1 ordinary objects (houses, mountains, etc.)

(2) We perceive2 ideas

As above, the introduction of material objects does not make (2) false. I think the issue is that you are misinterpreting the indirect realist's claim that we perceive2 qualia as the claim that we perceive1 qualia, and so you are guilty of the very same equivocation you insist on not letting pass.

The indirect realist claims that perception2 is direct perception — because the thing perceived is a constituent of the experience, and because it does not depend on perception1 — and that perception1 is indirect perception — because the thing perceived is not a constituent of the experience, and because it depends on perception2. -

Direct realism about perception

To keep it simple, it's subjective idealism without God. Minds — including qualia — are the only things which exist. Rather than mental phenomena emerging from neural activity there's just mental phenomena.

Is perception possible? If so, how can it be "normative and publicly assessable"? What are the "objects" of perception?

As for Berkeley, from here:

(1) We perceive ordinary objects (houses, mountains, etc.).

(2) We perceive only ideas.

Therefore,

(3) Ordinary objects are ideas.

I would think that your interpretation of perception must rule out (2) by definition. -

Direct realism about perceptionThe TLDR is that, on my view, perception is an intrinsically normative and publicly assessable act that is not fully reducible to causal analysis. In order for perception to be publicly assessable, whatever plays the role of "the object of perception" must satisfy criteria of re-identification and intersubjective reference that qualia, as such, cannot satisfy. — Esse Quam Videri

I'm curious, doesn't this rule out subjective idealism a priori? Or is it only the case that if subjective idealism is false then "perception is an intrinsically normative and publicly assessable act"? -

Direct realism about perceptionI thought you were talking about mentally verifying mind-independence. Michael said we can't do that. — frank

I'd like to clarify that this isn't what I said. I said that my intellect cannot reach out beyond my body to grasp the mind-independent nature of distal objects. Cognition is either reducible to or emerges from neural activity in the brain, and the only information accessible to it is information present in the brain.

I'm not an idealist. I believe that there is a mind-independent world and that the information accessible to me suffices to justify this belief. I just recognise that distal objects and their properties are only causally responsible for and not also constituents of first-person phenomenal experience, and so that this phenomenal experience is an epistemic intermediary. -

Donald Trump (All Trump Conversations Here)

I think that every citizen ought be allowed to vote, and that the government ought not introduce any economic or bureaucratic hurdles that can effectively disenfranchise the poor (or anyone else). If they cannot make it free and easy for every citizen to get ID then it should be the government's burden to prove that a voter isn't a citizen and not a citizen's burden to prove that they are. -

Direct realism about perception

As explained before, I'm not concerned with intentionality; I'm concerned with distal objects and their properties not being constituents of first-person experience, and so with phenomenal qualities being mental phenomena and epistemic intermediaries. Describing these phenomenal qualities — whether colours, smells, tastes, or pains — as being "the mode in which the world shows up" doesn't make what I'm saying any less true. If anything, this phrasing is vacuous; nothing more than the truism that this is what the world causes me to experience. -

Direct realism about perceptionWhereas I see two mutually incompatible accounts of perception that both happen to reject naive realism — one reifying phenomenal character into an inner intermediary, and one treating it as a mode of disclosure. — Esse Quam Videri

It's an epistemic intermediary because my intellect cannot reach out beyond my body to grasp the mind-independent nature of distal objects. The phenomenal character of first-person experience is the only non-inferential "information" accessible to me. That's an unavoidable consequence of B over A.

And I'm not entirely sure what you mean by reifying phenomenal character. If you think that I think that phenomenal character is some material object with extension and mass, and that I'm a homunculus looking at and touching this phenomenal character as a Cartesian theatre, then you are clearly misunderstanding me. -

Direct realism about perception

I see two different ways of talking about the exact same physical, physiological, and mental facts. These two different ways of talking about it create the illusion of a disagreement where there is none. A rejection of A (naive realism) in favour of B — however you choose to "interpret" B — amounts to indirect realism as I understand it. -

Direct realism about perception

Given that you agreed that naive color realism is false, I don't even know what you mean by saying "we directly perceive the distal object as colored". Once again, I think it's simply the case that you and I mean different things by the phrase "direct perception".

So I'm going to not use the words "direct", "indirect", or "intermediary" at all.

Group A believes that distal objects are constituents of first-person phenomenal experience such that the qualities of this first-person phenomenal experience are the mind-independent properties of these distal objects.

Group B believes that distal objects are only causally responsible for first-person phenomenal experience, that these distal objects and this first-person phenomenal experience are ontologically separate, and that at least some of the qualities (e.g. colour) of this first-person phenomenal experience are not the sort of things that can be mind-independent properties of these distal objects.

I am a member of Group B, and Group B is supported by our scientific understanding of physics, physiology, neuroscience, and psychology.

Nothing else is relevant to my position on the topic of perception. -

Direct realism about perception

You appear to accept that colours are mental phenomena and that seeing different colours is how we see different wavelengths of light and/or surfaces that reflect different wavelengths of light. I don't understand what else you think it would mean for mental phenomena to be an intermediary. This just is what I understand indirect realism to be, in contrast to the naive view that colours are not mental phenomena but mind-independent properties of distal objects which are more-than-causally constituents of first-person phenomenal experience. -

Donald Trump (All Trump Conversations Here)“Widespread”. That word just seems to always find itself in front of “voter fraud” whenever an apologist speaks of it. Is plain old non-widespread voter fraud ok in your books? — NOS4A2

Disenfranchising millions of eligible voters to prevent 1,600 ineligible votes over 40 years does more harm than good. If there were millions of fraudulent votes per election then ID laws would make more sense, but when there's barely any? It's absurd. It's like burning your house down to kill some spiders.

It doesn’t follow from here that they should be allowed to drive, fly, or vote in what ought to be secure elections. — NOS4A2

They absolutely should be allowed to vote.

All I'm hearing from you is "fuck poor people". -

Donald Trump (All Trump Conversations Here)Sorry, even the heritage foundation doesn’t know how many illegals have voted in elections. There is no way to know either way if no one has to prove their citizenship. — NOS4A2

So there's no evidence of widespread voter fraud.

But if they wanted to, they could get one. That’s the reality. — NOS4A2

It's not as easy as you're pretending it is. As an example from here:

19% of Americans without a driver’s license said they didn’t have one because of bureaucratic or economic barriers, such as not being able to afford the license or not having underlying documents like a birth certificate or Social Security card.

...

US citizens of color are also more likely than white citizens not to have documents that prove their citizenship. For example, older Black voters in the South and Indigenous Americans who were not born in a hospital may not have a birth certificate at all. -

Donald Trump (All Trump Conversations Here)I think it’s condescending that you’re treating people as if they cannot do the basic requirements of getting ID. In fact there are plenty of supports to help one to do so. Do you believe they were born in the woods or something? — NOS4A2

And yet millions don't have ID. That's the reality.

How do you know they almost never do if they cannot prove who they are? — NOS4A2

You're asking me to prove a negative. The burden is on the government to prove that someone is doing something illegally, and even the Heritage Foundation could only find ~1,600 cases over 40 years. -

Donald Trump (All Trump Conversations Here)So you are assuming, without evidence, that these people are American. — NOS4A2

I'm trusting that the people who came up with these numbers know what they're talking about. Whereas you seem to be assuming, without evidence, that anyone without ID isn't American?

Tough titty. If one cannot provide a drivers licence, he cannot legally drive. If he cannot provide a passport, he cannot fly. — NOS4A2

The right to vote is a bit more important than the right to drive and the right to travel abroad.

It’s the same as in your country, indeed any civilized country. In my state you can go to vital statistics to prove your birth and they can get you a birth certificate if you have lost one. You can use other IDs to get other IDs, and so on. — NOS4A2

Which is fine if it's quick, easy, and free, but a lot of people do not have the time or the money, especially if they can't drive because they don't have a driving license. I think you're in denial about the reality of how difficult many people's lives are.

Do you think illegals should vote in elections? — NOS4A2

No, and they almost never do. Whereas millions of legal citizens will be disenfranchised by ID requirements. The law does far more harm than good. -

Donald Trump (All Trump Conversations Here)I thought you were forced to vote or get a fine. — NOS4A2

That's Australia, not the UK.

You city gives you a birth certificate when born. You get a certificate of citizenship when you become a citizen legally. Is that not how it works in your country? — NOS4A2

I'm sure my parents were given my birth certificate when I was born. I don't have it. But that doesn't answer the question. Millions of Americans don't have their birth certificate, a passport, or any other relevant ID. So how do they then get one? -

Donald Trump (All Trump Conversations Here)Birth certificate, social security number, passport. — NOS4A2

And millions don't have them: https://www.npr.org/2024/06/11/nx-s1-4991903/voter-registration-proof-of-citizenship-requirement

So my question is: how does one get them without already having one of them?

Do you require ID to vote? — NOS4A2

We do as of 2023. That meant that almost 2,000,000 people couldn't vote in the 2024 general election. -

Donald Trump (All Trump Conversations Here)How do you know they are Americans if they cannot prove their citizenship? — NOS4A2

I don't know, I'm not the people who did the study.

But I'm curious, how does one get the identification to prove that one is an American citizen without already having proof that one is an American citizen?

As of January 2024, more than 7.2 million migrants had illegally crossed into the U.S. over the Southwest border during U.S. President Joe Biden's administration — a number higher than the individual populations of 36 states. — NOS4A2

Was this factoid going anywhere? -

Donald Trump (All Trump Conversations Here)

From here:

An estimated 21 million Americans do not have documents proving their citizenship readily available, and 2.6 million lack any form of government-issued photo ID, according to the Brennan Center for Justice and the University of Maryland's Center for Democracy and Civic Engagement.

And voter fraud is exceedingly rare:

Studies of voter rolls have found very few noncitizen voters. As of July 2024, the Heritage Foundation database includes only 24 noncitizen voting cases from between 2003 and 2023. In an audit of the 2016 elections, the North Carolina State Board of Elections found that 41 out of 4.8 million total votes were by noncitizens, and between 2017 and 2024, only three cases were referred for prosecution. In 2018, CNN reported that in the past three years, Kansas Secretary of State Kris Kobach had convicted three noncitizens of voting out of 1.8 million voters. A Brennan Center for Justice study of 2016 data from 42 jurisdictions found an estimated 30 incidents of suspected noncitizen voting out of 23.5 million votes cast (or .0001% of votes). A review in Georgia found that no potential noncitizens had been allowed to register to vote between 1997 and 2022. In September 2024, an audit in Oregon found that more than 1,200 possible noncitizens had been added to the state's voter rolls by mistake; the issue was quickly fixed and no more than 5 noncitizens had cast ballots.

So the law would do overwhelmingly more harm than good. -

Is Objective Morality Even Possible from a Secular Framework?

The context of my comment was as a response to someone claiming that moral facts must be dictated by some God. I was asking what he would do if his God were to dictate that everyone is morally obligated to kill blasphemers. Would he obey his God? -

Donald Trump (All Trump Conversations Here)The cops were already looking into Epstein, when the alleged phone call was made. — Punshhh

Yeah, that's why it's weird. Someone calls claiming to have knowledge that would help the investigation, and then it's never followed up and never mentioned until 13 years later.

Also if Trump thinks Maxwell is "evil" then why allow her to move to a minimum security prison against standard protocol, and why refuse to rule out a pardon? Does he genuinely think that the evidence that led to her conviction does not prove her to be as "evil" as he thinks/knows she is? -

Donald Trump (All Trump Conversations Here)Sometimes you just don’t want anyone to know you’re an informant. Do you suspect something nefarious? — NOS4A2

I suspect that we can never trust anything Trump or his lawyers say about the matter.

Then the sheriff of Palm Beach must have lied to the FBI, which is a crime. — NOS4A2

Well it's a little peculiar that the sheriff in charge of the investigation didn't include this in any contemporaneous notes during the investigation, or call Trump in to be interviewed about what exactly he knows. How often does someone call the police to tell them that they know that someone is raping children, and then it's just left at that? -

Direct realism about perceptionRight — phenomenal character is necessary for awareness of the apple. But necessity (or counterfactual dependence) is not mediation. I can’t see the apple without my eyes, but my eyes aren’t what I see. Phenomenal character is what my awareness of the apple consists in — the mode of perceiving — not a second object I perceive on my way to the apple. — Esse Quam Videri

I'm not saying that the colour red is an object, just as I wouldn't say that my headache is an object. I'm saying that I see the colour red, that the colour red is a mental phenomenon, and that seeing the colour red (usually) mediates seeing 700nm light and/or a surface that reflects 700nm light.

You might say that "the colour red is what my awareness of 700nm light and/or a surface that reflects 700nm light consists in", but notice that there's no "X is what my awareness of the colour red (or a headache) consists in". That's why my perception of the colour red (or a headache) is direct/unmediated/immediate in a way that my perception of 700nm light and/or a surface that reflects 700nm light isn't. This sense of direct/unmediated/immediate perception is the sense that the naive realist claims about our perception of apples — that there is no "X is what my awareness of apples consists in", only apples as literal constituents of first-person experience — and is the view that the indirect realist is opposing. -

Donald Trump (All Trump Conversations Here)

That's weird, because according to this from 2019:

Trump Organization attorney Alan Garten told Politico in 2017 that Mr Trump "had no relationship with Mr. Epstein and had no knowledge whatsoever of his conduct". Mr Garten added this week that Mr Epstein was banned from Mar-a-Lago since the criminal charges were filed against him.

When asked on Sunday about the charges against Mr Epstein, Mr Trump told reporters "I don't know about it".

Although, from your own article:

A Department of Justice official told ABC News in a statement that the agency was "not aware of any corroborating evidence that the President contacted law enforcement 20 years ago."

So who the hell knows.

Michael

Start FollowingSend a Message

- Other sites we like

- Social media

- Terms of Service

- Sign In

- Created with PlushForums

- © 2026 The Philosophy Forum